Has the Enforcement of Neo-liberal Policies by International Institutions and/or Organisation Undermined the Institutional Ability and Political Power of National Governments to Set Their own Agenda? Discuss with Reference to Particular Examples.

It is obvious that the question posed is an extremely important one at least because the answer should give us direction for further international policy-making. The question is important, but unfortunately also very difficult and complex. To answer whether the enforcement of neo-liberal policies by international institutions and/or organisations has undermined the institutional ability and political power of national governments to set their own agenda in such a short text is possible only if one makes a simple assumption. The institutional ability will be seen as being derived from political power; therefore only power will be concerned in the essay, as it will be assumed that institutional abilities follow from sufficient political power. Also no differentiation between international institutions and organizations will be held since it would not affect the argument. This should allow us to answer the question more easily.

However, in order to do so properly, a comprehensive approach is adopted. Not only it is discussed whether the power was undermined, but also whether it was undermined equally over states. These two questions will be answered in the first and second chapter. It will be shown that the power of national governments was undermined in all states, although not in all equally. The third chapter will try to show how this fact can explain why powerful states promote neoliberal policies even though their domestic power is diminished due to it as well. In each of the chapters the nature of the crucial phenomenon discussed will be treated, then some theoretical explanation for it will be presented and at the end illustrative examples will be given.

Power of the Nation-states

This chapter attempts at answering a single question: Has the power of the nation-states been undermined? The structure of the answer is as was suggested in the introduction: firstly we observe the nature of a crucial variable – domestic power – , then a theoretical account of the issue is given and at the end some examples are presented to illustrate the processes discussed.

Since at least Thomas Hobbes, the state has been seen as an organism created to prevent people from violence: both from inside and outside. A concept of internal sovereignty was developed to explain the power of the state towards its own people (later citizens). Heywood gives a simple account: “Internal sovereignty is the notion of a supreme power/authority within the state, located in the body that makes decisions that are binding on all citizens, groups and institutions within the state’s territorial boundaries” (2000: 37). Domestic power is therefore an absolute ability of the governing body to implement its policies. The word ‘absolute’ is crucial. State does not compete for power with anybody; it either is able to collect taxes, enforce law etc., or it is not.

From this point of view, the theoretical (second) part of the problem becomes instantly clearer. With increasing ‘complex interdependence’ (concept developed by Keohane, Nye: 1987) meaning “sensitivity or vulnerability to an external force” (Reinicke, 1998: 55), it is clear that states do lose their ability to implement policies. Even the most reserved authors admit that there is some move. Krasner argues that the states’ loss of power is only quantitatively higher than in the past, not qualitatively (Krasner, 1999: 34). Others, to the contrary, claim, that the move of power from states to economic bodies changes the nature of politics substantially (Strange, 2000: 149). Terms like ‘borderless world’ are used in connection to such positions (Held, 1999: 3). All this suggests one thing: whatever position authors hold, they all admit that there is some move of the power from the nation-states to inter- or supra-national bodies. The domestic power of the states is decreasing and, according to most authors, is decreasing fundamentally.

The question remains where does the power go. In many areas, the answer is still unclear. In economics and political economics (the topic of this essay) it seems to be very much clear: to the trans-national corporations (TNCs). Their economic power is such that they are able to influence states’ policies profoundly. Sklair argues that “major globalizing corporations play an increasingly political role in Europe, as do their equivalents in other parts of the world” (2002: 73). This is a serious threat to states’ economies, but, even more importantly, to the legitimacy of their political systems. Reinicke discusses it in length but a single sentence is sufficient to present the threat to politics from the TNCs in the globalizing world: “a government no longer has a monopoly of legitimate power over the territory within which corporations organize themselves” (1998: 65). States are losing their domestic power. Since the loss is due to adopting neoliberal economic policies (lowering control over the TNCs) and the neoliberal policies are enforced by some international organizations (IMF, WB, WTO), it is clear that it is their policies that are enhancing and accelerating the processes discussed.

To find an illustration of the policies lowering states ability to design and implement its own agenda is not difficult: two major states which witnessed serious crises in the last years can serve as good examples – Argentina and Russia. In Argentina, it is argued, the neoliberal policies imposed by the IMF caused a financial (and consequently economic, social and political) crisis in 2001. The power of the IMF in relation to Argentina bled it to enforce its neoliberal economic policies causing disastrous social changes. The reason for that was the “subordination of politics to the logic of money” (Dinerstein, 2004: 280). Teubal (2000) argues in a similar way; the policies prescribed by the IMF and the WB caused redistribution of the wealth to the rich and transformation of the economy in such a way as to serve export- and luxuries-oriented industries. The case of Russia is similar. The neoliberal policies enforced by the IMF and the WB during the 1990s caused that most of the national wealth disappeared. As Stiglitz claims (2002: 145), “[t]he IMF had encouraged the government to open up its capital accounts, allowing a free flow of capital … [which] facilitated a rush of money out of the country“.

As the examples show and the theory explains, the neoliberal policies do undermine states’ ability to perform its policies. This is, however, only the first part of the question. Another, and perhaps even more important one, is yet to be answered.

Loss of Domestic Power: Equal or Not?

This chapter attempts at answering the second important question: is the loss of power of the nation-states equal or not? From the previous chapter we know that the national governments’ power is decreasing and that this process is enhanced and accelerated by international organizations such as the IMF, the WB and the WTO. Thus, if one wants to answer the question, he should focus on these organizations to see what relation there is between the policies they promote and the equality of the distribution of power. After that, it is possible to theorize the distribution of the loss of power. At the end, again, some illustrative examples are offered.

The problem with international organizations is that they are not democratic. Most authors would argue that the economic international organizations are dominated by the United States, maybe by Europe and Japan in the second rank. This claim is supported by a widespread use of the term ‘Washington consensus’ accounting for the policies prescribed by the IMF, the WB and other institutions. The same understanding of the issues can be derived from the voting power of individual states in the institutions. In the IMF, the five most powerful states possess 38.42% of voting power, out of which only the United States16.79%. For comparison, China, India and Bangladesh altogether account for less than 6% of the voting power (IMF, 2008). In the WB, the situation is only very slightly less unfavourable for small members (World Bank, 2008). In the WTO, the situation is far less clear because the voting system does not reflect the real power. However, there is no reason for assuming that the political and economic dominance of the few states is not reflected there as well. The global governance institutions reflect hugely the interests of the very few nations.

Furthermore, the reality is that the importance of these institutions has been dramatically increasing. Peet argues in this sense:

globalization has been accompanied by the growth of power of a few prodigious institutions operating under principles that are decided upon undemocratically, and that drastically affect lives and livelihoods of a world of peoples (2003: 3).

This process is not only empirical, it can be also easily explained theoretically. The power is a self-reinforcing mechanism and thus the few states are able to push their views in the international organizations. Once these do reflect positions of the strong, they are allowed much bigger power in the global governance. Moreover, these organizations are able to shape the opinions of individual states in the ‘right’ manner. This argument is based on the power theory of Steven Lukes (2005: Ch. 1). Dinerstein uses it to explain the changes of policy-making towards IMF-prescribed models in Argentina since the 1970s (2004: 270 – 271).

What we can observe, therefore, is that some states – US, GB, France, Japan and few others – are actually not losing so much power as others because they are able to promote their positions to the policies of the organisations designed to ‘regulate’ international economy. Thus, one could successfully argue that even though all states are losing their domestic power, some are able to reduce these losses relatively more than others. The EU and the banana-trade dispute is the example of how the EU loses some of its power by participating on the global governance. Due to its obligations to the WTO, the EU was forced in the dispute initiated by the US to abandon its trade policies discriminating some of the banana importers. The EU had to adopt policies unfavourable to its interests (Read, 2001). However, only marginal interests were harmed. In Uzbekistan, to the contrary, the adoption of the liberal policies in tobacco industry – prescribed by the WTO – led to dramatic changes. As Gilmore et al. show, in Uzbekistan the rapid privatisation of the tobacco industry led to fall in prices and consequent increase in consumption of tobacco products. The neoliberal policies enabled the tobacco concerns to influence substantially the taxation system and the health-prevention programmes of the Uzbek government in such a way as to increase the people’s consumption. The policies of the WTO and the IMF can be seen as presenting a serious danger for health security of Uzbekistan and other states of the former Soviet Union(Gilmore et al., 2007).

For some states, neoliberal policies are detrimental, whereas to others they may cause only limited damage. But still, why do the powerful states promote these policies, if they suffer from them? This is the question for the last chapter.

Explaining the Puzzle

Based on observation made in the previous chapter, this chapter attempts at explaining why powerful states continue promoting policies that are seemingly harmful to them. Firstly, the nature of power in the international politics is described. Afterwards, a theory is presented to give the explanation for the puzzle. At the end, some examples are given again.

In the first chapter, the concept of internal sovereignty was described showing that domestic power is by its essence absolute; it is a capability of government. External power, to the contrary, must be seen as inherently relative. It exists only in relation to other states which are ontologically equal. Within the state, the citizens are subordinated to the power of the government. In international politics, nobody is subordinated to anybody. The power is a result of competition; by its essence, it is a relation. In the words of Heywood, “[e]xternal sovereignty relates to a state’s place in the international order and its capacity to act as an independent and autonomous entity” (2000: 37). In international politics, state competes for power with others.

This is a broad view accepted by most mainstream international relations theorists, but in crystal form it is represented by the realist school of international relations. According to scholars such as Morgenthau (2005) and Waltz (1979), the states struggle for power in order to survive in the hostile field of international politics. In their view, states that do not adopt policies to increase their power in relation to other states will necessarily perish. The absolute (economic) gains are not a sufficient motivation for a state to enter cooperation as long as the other state gets from the cooperation more. Furthermore, it is worth competing with other state even if it decreases wealth of the state as long as the others are harmed more. The US, the EU and others do not have to be afraid of liberal policies. They lose some power because of them; but the other states lose much more because they are not able to project their views to the policies of the global governance institutions.

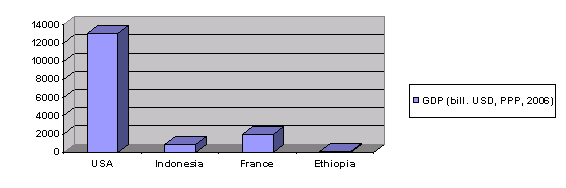

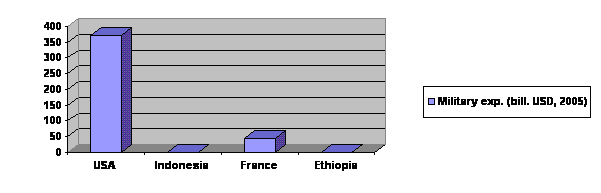

It might be useful to illustrate the theory with the distribution of power over some countries. Only two indicators are chosen to show the distribution: GDP and military expenditures. Two pairs of states are chosen: US and Indonesia(each approx. 220 – 270 mil. inhabitants) and France and Ethiopia (each approx. 55 – 70 mil. inhabitants).

The first graph shows economic power of the respective states (data from CIA, 2008).

The second graph shows military power of the respective states (data from CIA, 2008). Differences are even more striking.

Some states are more powerful; others are less. It is absolutely clear that the power superiority of some states is reflected in the institutions of global governance. This can explain why powerful states do enter global governance institutions even though it undermines their power. The power of the others is actually undermined more. The puzzle is explained. The powerful states are motivated to act against their apparent interests because in the long run they expect this behaviour to bring them more profits, as they will be able to increase their relative power in the international politics.

Conclusion

They essay question was provisionally answered in the first chapter. Yes, the political power of national governments has been undermined by the neoliberal policies. But if one says that, another problem arises instantly. Why do states promote these policies in the international organizations if these harm them? The second and the third chapter attempted at answering this question. It was shown that the reason lies in the nature of power in international politics. States compete for power with others and therefore prefer such policies as long as others are harmed by these more. This seems to be the situation today.

The overall conclusion is awkwardly trivial: power relations matter. Having said that, new question for next research can be identified. What should be the weak states’ strategies in such a situation? How can they act if they have not enough power? The answer seems to be suggested by East Asian states: to overcome the temporary social problems and to ‘sacrifice’ today’s consumption for tomorrow’s investments and economic progress. Then, power will come by itself. The instruction is simple. The difficulty comes if the instructions are followed, today’s consumption is sacrificed, but the tomorrow’s investments do not come. In such situation, the sacrifice loses sense. For some states, unfortunately, this is the situation today. In this sense, the problem seems to be rather in domestic political elites unable to govern own agendas than is economic system. Only when the elites provide reasonable and accountable governance will the sacrifice be sensible. Unfortunately, more power going to TNCs will probably not help the situation at all.

References

CIA, 2008. The World Factbook 2007 [online]. Available from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html [Accessed 8. 1. 2008]

DINERSTEIN, A. C., 2004. Beyond Crisis: On the Nature of Political Change inArgentina. In: P. Chandra, et al. (eds). The Politics of Imperialism and Counterstrategies.Delhi: Aakar Books

GILMORE, A. et al., 2007. Transnational tobacco company influence on tax policy during privatization of a state monopoly: British American tobacco andUzbekistan. American Journal of Public Health. 97 (11)

HELD, D. et al., 1999. Global Transformations. Politics, Economics and Culture. Stanford:StanfordUniversityPress

HEYWOOD, A., 2000. Key Concepts in Politics.Basingstoke: Palgrave

IMF, 2008. IMF Executive Directors and Voting Power [online]. Available from: http://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/memdir/eds.htm [Accessed 8. 1. 2008]

KEOHANE, R. O., NYE, J. S. Jr., 1987. Power and Interdependence Revisited. International Organization. 41 (4), pp. 725 – 53

KRASNER, S. D., 1999. Globalization and sovereignty In: D. Smith, D. Solinger, S. Topik. States and Sovereignty in the Global Economy.London: Routlege

LUKES, S., 2005. Power: A Radical View. 2nd ed.Basingstoke: Palgrave

MORGENTHAU, H. J., 2005. Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace. 7th ed.New York: McGraw-Hill

PEET, R., 2003. Unholy Trinity: The IMF, World Bank and WTO.London: Zed Books

READ, R., 2001. The Anatomy of the EU – US WTO Banana Trade Dispute. Estey Centre Journal for Law and Economics in International Trade. 2 (2), pp. 257 – 282

REINICKE, W. H., 1998. Global Public Policy: Governing without Government?.Washington: Brookings Institution Press

SKLAIR, L., 2002. Globalization. Capitalism and its Alternatives. 3rd ed.Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress

STIGLITZ, J., 2002. Globalization and its Discontents.London: Penguin Books

STRANGE, S., 2000. The Declining Authority of States In: D. Held, A. McGrew (eds.). The Global Transformations Reader.Cambridge: Polity

TEUBAL, M., 2000. Structural Adjustment and Social Disarticulation: The Case ofArgentina. Science and Society. 64 (4)

WALTZ, K. N., 1979. Theory of International Politics.New York: McGraw-Hill

WORLD BANK, 2008. Boards of Directors. Voting Powers [online]. Available from: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/EXTABOUTUS/ORGANIZATION/BODEXT/0,,contentMDK:21429866~menuPK:64020035~pagePK:64020054~piPK:64020408~theSitePK:278036,00.html [Accessed 8. 1. 2008]

—

Written by: Michal Parizek

Written at: University of Bath

Written for: A. Dinerstein

Date written: 2008

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- China’s Instrument or Europe’s Influence? Safeguard Policies in the AIIB

- Gendered Implications of Neoliberal Development Policies in Guangdong Province

- Liberal Peace and Its Crisis: The Revival of Authoritarianism

- Crisis or Continuation? The Trump Administration and Liberal Internationalism

- The European Quality of Government Index: A Critical Analysis

- Limits of Liberal Feminist Peacebuilding in the Occupied Palestinian Territory