Globalization literature commonly hold that as sovereign states are faced with the challenges and opportunities of global integration, they are increasingly acceding to treaties which coordinate laws and policies that have traditionally been consigned to the domestic sphere. This expansion of treaty law bears significantly on federal states, such as Canada and Australia, which are defined by an internal division of political powers. Despite the potential conflicts this observation raises, there has been relatively little scholarly investigation into the relationship between international global integration and federalism.

Through an examination of Australian and Canadian constitutional law and jurisprudence, this paper examines how the internal division of treaty-making and treaty-implementing competencies affects the jurisdictional balance of power between central and subunit governments in federal states responding to globalization. This paper argues that in federations such as Australia, highly centralized treaty powers provide an avenue for the central government to encroach upon the jurisdictions of federal subunits. This, in turn, leads to a more centralized federation. Conversely, in federations such as Canada, more decentralized treaty powers tend to preserve the jurisdictional balance of power and maintain equilibrium between central and subunit governments.

All states are currently facing the challenges and opportunities of globalization. As countries become more integrated, it behoves them to coordinate laws and policies. Consequently, the boundary between domestic and foreign policy is weakening.[1] Integration also entails the proliferation of international treaties, which are becoming broader in scope; that is, they deal more and more with matters traditionally consigned to domestic politics. This is construed as the first independent variable of the present investigation. However, federations vary in how they adopt treaties. Treaty-powers may be more or less centralized along two axes: treaty-making and treaty-implementation. To take two examples, Australian treaty-power is highly centralized along both axes, whereas Canadian treaty-power is more decentralized. These differing institutional formulas are the second independent variable.

The dependent variable examined is the maintenance of political balance between central and subunit governments (figure 1).[2] This paper employs an institutional focus to explain why globalization has different impacts on federations: why does it cause some federations, like Australia, to centralize while others, like Canada, retain a federal balance which protects subunit jurisdictions?[3] As treaties become broader, encroaching upon areas of subunit jurisdiction, centripetal forces occur in federations with centralized treaty-powers while centrifugal forces occur in federations with decentralized treaty-powers.[4] This is seen with reference to the dynamics of intergovernmental relations in the Australian and Canadian federations. Such questions are important because the maintenance of a balance is necessary to federal states, influencing political stability and the ability to adapt to globalization.[5] It is also important to account for globalization’s disparate impact on federations as the relationship between globalization and federalism is not well studied.[6]

This argument is developed through several sections. I first examine the phenomenon of treaty broadening. I then discuss the differing configurations of treaty-power in federal states. Third, I compare Australian and Canadian treaty-making powers and how this affects the dynamics of intergovernmental relations. Finally, I conclude with a discussion of how treaty-making powers affect the federal balance.

Globalization and international law. Globalization entails the intensification of relationships which transcend state borders and encourage mutual integration and interdependence. These transnational ties take a wide variety of forms: from economic to environmental, from cultural to communicational, and so on.[7] Yet, globalization does not affect all countries in the same way or with equal intensity. Its impact is influenced by geography, demographics, and more importantly by political, institutional, and constitutional structures.[8]

As Lazar, Telford, and Watts explain, “in response to [globalization, there] is a growing body of international [treaty] law.”[9] States must coordinate policies to manage interdependence in areas such as investor rights, controls on procurement and technical standards.[10] As neo-liberal institutional scholars point out, treaties encourage cooperative transnational governance by circumventing collective action problems between legally autonomous parties.[11] Two trends are important to note. The first is an expansion of treaty law. International law is shifting from a customary-basis to a more formal treaty-basis.[12] Second, treaty subject-matter is broadening. An increasing number of treaties oblige states to change domestic statutes and policies.[13] As Bernier notes,

matters which fifty years ago were regulated only by national law, or not regulated at all, have now become the objects of international obligations. More specifically, matters within the jurisdiction of [federal subunits] have become the object of international agreements. For many federations, this [raises] serious problems.[14]

To understand why this bears on the federal balance, it is important to examine the fundamentals of international treaty law and how this relates to federal systems.[15]

The Federal Problem. Treaties are the most consensual form of international law, as a state is not legally bound to oblige itself.[16] The capacity to consent to obligation is vested in entities possessing legal personality.[17] This is also equated with responsibility; the ability to oblige oneself means that one is also accountable if obligations are breached.[18] Responsibility is embodied in the principle of pacta sunt servanda and codified in article 26 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969).[19] Personality and responsibility, as legal concepts, are premised on unitary states where the government which consents to obligations can easily abide them; this is not the case for federal states, which vary in terms of how they assign treaty-powers.[20]

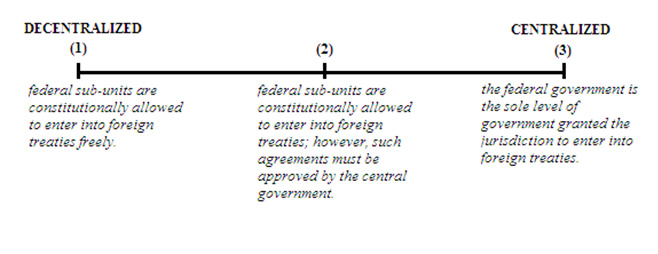

It is important to distinguish between treaty-making and treaty-implementation powers, which are the powers to oblige oneself and abide obligations, respectively.[21] Treaty-making power corresponds with personality. In federal systems with centralized treaty-making power, personality is vested exclusively in the central government; in decentralized systems, such as Belgium and Switzerland, this power is accorded to subunits, which may conclude treaties in their areas of jurisdiction; and, in intermediate federations, subunits may make treaties, but only with central government approval (figure 2).[22] In many federations, treaty-making is formally centralized and intermediary in practice. In the United States, for instance, article 1(1) of the Constitution denies states treaty-making power, yet the Department of State has occasionally allowed them to enter into international obligations.[23] Similarly, article 32(3) of the German Basic Law permits länder to conclude treaties if approved by Berlin.[24] The common dominance of central governments in treaty-making is typically understood by scholars such as KC Wheare, RC Ghosh, and GR Morris, as maintaining a united national voice in foreign relations.[25]

In both the centralized and intermediary positions, the central government is responsible for the compliance of subunits.[26] In the intermediary position, this occurs because the central government acts as the arbiter of subunit personality and is thus the ultimate possessor of personality and responsibility. This is reflected in article 27 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969), which asserts that a state “may not invoke the provisions of its internal law for its failure to perform a treaty.”[27] Both Canberra and Ottawa have, for instance, been censured for subunit actions which breached treaties.[28] Federations may respond in three ways to the problem of responsibility. First, they may circumvent liability with a Federal State Clause (FSC). FSCs limit responsibility in areas of subunit jurisdiction.[29] The North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation, for instance, includes such as clause.[30] However, their use is contentious because unitary states argue that this creates legal inequalities.[31] Thus, the use of FSCs by both Australia and Canada has declined markedly in recent times.[32] Second, as in Canada, Federal states may attempt to ensure that subunits will comply with a treaty’s provisions prior to its ratification.[33] A final scheme is to extensively centralize both treaty-powers, as in Australia.

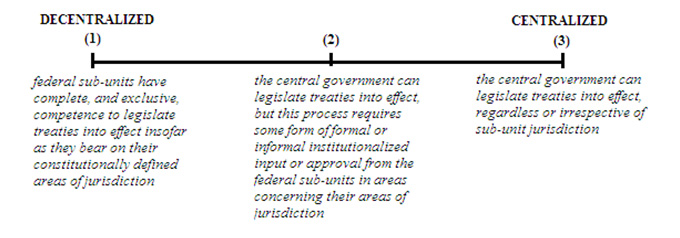

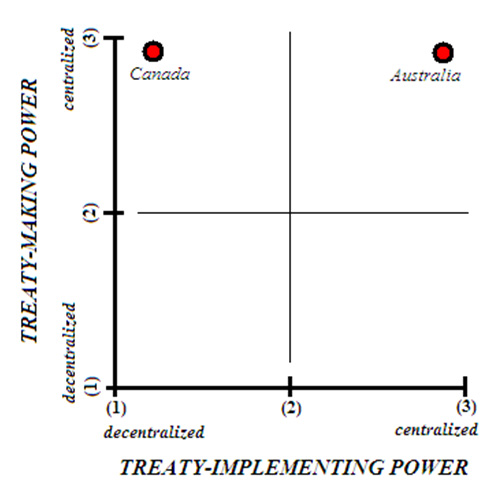

Federations also differ in the allocation of treaty-implementing power, which is the power to bring domestic statutes into compliance with treaties.[34] In centralized systems, the central government can legislate a treaty into effect, even when its subject matter encroaches upon subunit jurisdiction; in decentralized systems, subunits must legislate such a treaty into effect; and, in intermediate systems subunits are able to influence treaty implementation through intragovernmental mechanisms (figure 3, 4).[35] For instance, the United States and Germany are both intermediate systems. In the United States, treaties automatically become domestic law once ratified. Article 6 of the American Constitution states that treaties “shall be the supreme law of the land.”[36] It was established in Missouri v Holland (1920) that ratified treaties also overrode state laws.[37] Yet, states are protected by article 2(1), which dictates that a supermajority in the regionally representative Senate is required for ratification.[38] Similarly, the German Basic Law vests with the federal government control over implementation.[39] Yet it limits this power by stipulating that when a treaty bears on länder jurisdiction, it must be approved by the regionally representative Bundesrat.[40]

When most federations were founded, treaties were limited to policy areas already under central jurisdiction such as diplomacy, war and peace, and trade.[41] In this context, centralized treaty-powers bore little consequence to the federal balance.[42] Yet, from the 1970s onward, federations have had to cope with the broadening of treaties into subunit jurisdictions. Consequently, the constitutional division of treaty-powers has the potential to alter the balance of federal states.[43] A comparison of Canada and Australia confirms this hypothesis.

CASE COMPARISON

Neither the Australian nor Canadian Constitutions deal explicitly with treaties. Consequently, judicial review has played a crucial role in determining the configuration of treaty-powers.[44] Intergovernmental relations are dynamic, but are strongly influenced by this formal distribution of power.[45] In Australia, centralized treaty-power encourages a centripetal dynamic and dysfunctional intergovernmental relations. Conversely, in Canada, treaty-powers promote a modestly centrifugal dynamic which protects the federal balance and necessitates intergovernmental relations premised on federal and provincial equality.[46]

Australia. Australia’s experience of globalization is influenced by its geographical position.[47] Its main regional ties are the Closer Economic Relations arrangement with New Zealand, its involvement with Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, and its affiliation with the Association of South East Asian Nations.[48] Australia is party to numerous treaties covering a wide range of issues, from human rights to the environment, which bear on subunit jurisdictions.[49]

Like Canada, Australia is a parliamentary, jurisdictional federalism with a commonwealth and state governments. Distinguishing Australia from Canada is an effective Senate, although it is not strictly regionally representative as it is elected on a proportional representation scheme.[50] Finally, it is similar to Canada in that treaty obligations must be legislated into effect.[51] Australia’s Constitution deals with treaties only vaguely. As in Canada, the Australian federation was founded as a colony and consequently a situation in which it would be vested with international personality was not foreseen. Yet, treaties concluded under the auspices of the British Empire still needed to be legislated into force. [52] Thus, section 51(29) of the Constitution states,

the Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order and good governance of the Commonwealth with respect to… external affairs.[53]

As Australia became independent, treaty-powers came to the fore and continues to be debated. Both treaty-making and treaty-implementing powers became highly centralized through the High Court of Australia.[54] International personality, as in Canada, is vested in the central government via the governor genera’s office. Unlike Canada, this power has been relatively uncontested by subunits.[55]

The more heated debate has concerned treaty-implementation powers, where a centralizing opinion within the High Court clearly dominates.[56] In the case of R v Burgess (1936), which dealt with the status of legislation Canberra had passed in accordance with an aerial navigation treaty that encroached upon states’ jurisdiction over transportation, Chief Justice Latham ruled that,

the commonwealth has [exclusive] power to enter into international agreements and to pass legislation to secure the carrying out of such agreements according to their tenor even [though] the subject matter of the agreement is not otherwise within commonwealth legislative jurisdiction.[57]

This has established the precedent that the commonwealth may encroach upon states’ jurisdiction to implement treaties (figure 4).[58] When challenges reemerged, in cases such as Koowarta v Bjelke-Peterson (1982), Commonwealth v Tasmania (1983), and Victoria v Commonwealth (1996), this precedent was upheld.[59] According to Chief Justice Mason of the High Court, treaty-powers “must be interpreted generously, so that Australia is fully equipped to play its part on the international stage.”[60] This seems to embody the centralizing assumptions of Wheare, Ghosh and Morris. Furthermore, in Victoria v Commonwealth, the High Court explicitly stated that even in the contemporary context of broadening treaty obligations, the commonwealth’s treaty-power was supreme.[61] Crawford states that this case represents “the final gasp of states’ rights.”[62] Indeed, the only formal limitation on commonwealth treaty-power is that the High Court may deem a piece of legislation ultra vires if it both invades state jurisdiction and is unnecessarily broad with respect to the treaty in question.[63]

Australia’s states have attempted to influence foreign policy in two ways. In areas of state jurisdiction, some have made modest attempts to conduct foreign policy; although the agreements made are not legally binding.[64] Furthermore, states may be allowed to implement treaty legislation, usually because they are seen as the better equipped than Canberra to oversee compliance. Yet, it is demonstrative of the commonwealth’s dominance in this field that even in these cases, ostensibly identical statutes are passed in each state.[65] This leaves little room for regional flexibility in terms of treaty compliance.

Consequently, states have sought a more balanced treaty process through intergovernmental mechanisms.[66] This has primarily taken place within the Council of Australian Governments.[67] Such agreements were first established in the 1970s and have since been renegotiated in 1982, 1985, and 1991.[68] The latest reform occurred in 1996.[69] The Principles and Procedures for Commonwealth-State Consultation on Treaties has met with mixed success at best. Successes include adherence to the principle that all treaties must be tabled in the legislature fifteen days before ratification.[70] This was sought by the states, which, knowing that a formal veto over treaties was unobtainable, may attempt to establish Senate opposition to ratification, as the Senate is rarely controlled by government.[71] States are also occasionally included in treaty negotiations. Yet, only one state is typically included which then represents all states’ interests. This decreases their ability to take contrary opinions on treaty matters.[72] There are also serious failures. First, the Treaty Council, which was established as an information sharing forum, is defunct and has only convened once. This is because Canberra must consent to convening it.[73] Second, the Joint Standing Committee on Treaties, which scrutinizes treaties and releases impact reports to states, was also established.[74] However, this body is often controlled by the government and has only opposed the ratification of only one treaty, which Canberra nonetheless ratified. Furthermore, it is criticized for its failure to consult with the states.[75] Intergovernmental mechanisms remain weak and reveal the lack of institutional incentives for Canberra to seriously commit to a more balanced treaty system.[76]

Canada. Canadian experiences of globalization are dominated primarily by its ties to the United States and membership in the North American Free-Trade Association.[77] Canada, like Australia, is also party to numerous treaty organizations and has experienced the proliferation of treaties which increasingly encroach upon sub-unit jurisdiction.[78] Additionally, it is important to note Canada’s regionalized economy, which means provincial interests are likely to be diverse regarding globalization.[79]

As in Australia, the Canadian Constitution is largely silent on treaty-powers. Hans J Michelmann explains, “the federal [and provincial] authorities operate, essentially, in a constitutional vacuum.”[80] As in Australia, treaty-powers became the subject of debate as Canada gained independence.[81] In terms of international personality, Canada has centralized treaty-making power vested in Ottawa through the Governor General’s office, as in Australia. This was most clearly stated in the Letters Patent (1947).[82]

Unlike Australia, treaty-making powers have been contested. Quebec has claimed that provinces are able to conclude treaties in their areas of jurisdiction by virtue of the Lieutenant Governors.[83] Despite judicial victory in Bonanza Creek Gold Mining Company Limited v the King (1916), the dominant legal opinion has favoured the federal government’s denial of provincial personality.[84] Dupras states Ottawa’s view: “the [federal government] is the only Canadian government that has an international personality.”[85] As subunit personality is granted either by the constitution or the consent of the federal government, Ottawa’s position effectively denies the provinces personality.[86] Quebec has further pursued foreign policy through non-binding agreements, or ententes, which the Supreme Court has found to be permissible.[87] On rare occasions, Ottawa has recognized these agreements,[88] however it remains the ultimate arbiter of international personality and thus of responsibility for compliance.[89]

Canada’s treaty-implementation power is much more decentralized than in Australia.[90] This has centered on the differing interpretation of section 132 of the British North America Act (1867), which states,

the Parliament and Government of Canada shall have all Powers necessary or proper for performing the Obligations of Canada or of any Province thereof, as Part of the British Empire, towards Foreign Countries, arising under Treaties between the Empire and such Foreign Countries.[91]

Section 132 has been seen as applying only to treaties concluded under the auspices of the British Empire. In the precedent setting case of Attorney General for Canada v Attorney General for Ontario (1937), otherwise known as the Labour Conventions Case, Lord Atkin, speaking for the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, struck down legislation passed by Ottawa to implement an International Labour Organization agreement as it impinged upon provincial jurisdiction.[92] This means that treaty legislation must be enacted by the provinces if it is within their jurisdiction (figure 4).[93] Hogg explains the problem this produces,

because legislative power is distributed among a central and several [provinces], there is the possibility that treaties made by the central government can be performed only by the [provinces] which are not controlled by the central government.[94]

It is unlikely that the federal government could upend this precedent, given the Supreme Court’s reticence to overturn precedents bearing on the federal balance, as stated by Justice Deschamps in the Reference Re Employment Insurance Act.[95] There is, however, the prospect of broadening treaty-implementing powers with recourse to Ottawa’s peace, order, and good government or trade and commerce powers, which were expanded in the 1980s in cases such as General Motors v. City National Leasing (1989) and Crown Zellerbach (1988).[96] However, in order to invoke these powers, an issue must shown to be of national concern. While some scholars argue that a treaty is itself a matter of national concern, this position has not been judicially affirmed. As both levels of government are wary of the outcome of such a challenge, it is unlikely either with attempt to broaden their treaty-powers in such a way.[97]

In response to this situation, Ottawa could feasibly confine itself to only negotiating treaties within its jurisdiction. This was the federal government’s approach for some time. For instance, it denied signing a treaty in 1948 that would have mandated teaching the United Nations Charter in classrooms, as this was within provincial jurisdiction.[98] Though this approach is certainly in line with the “water-tight compartments” view of federalism, it is increasingly impracticable in a globalized world requiring transnational policy harmonization.[99] Therefore, Canada relies extensively on intergovernmental relations to gain provincial compliance with treaties.[100]

Unlike Australian states, Canadian provinces enter these relations armed with a de facto veto over treaties concerning their jurisdiction.[101] While Robinson argues that Ottawa may use its spending power to induce provincial compliance, he was writing prior to the implementation of the Social Union Framework Agreement, which constrains Ottawa’s caprice in matters to use its fiscal transfers.[102] Though it is not a binding agreement, Ottawa may be wary of the political fallout associated with capriciously using spending power in such a way, especially if it were to negatively impact service provision to Canadian citizens in a given province. Thus, Ottawa’s safest strategy is to seek provincial approval prior to ratification, or it risks provincial refusal to implement the treaty, which would place it in breach of treaty.[103] As Simeon explains, “Ottawa needs to keep the provinces onside if it is to succeed in international forums; provinces need federal support for their objectives.”[104] This allows provinces to conditionally delegate the power to negotiate treaties to the federal government.[105] This dynamic promotes a balance between the two levels of government.

Intergovernmental mechanisms, however, remain largely informal and are carried out through executive federalism.[106] Perhaps the most notable example was the negotiation of the Free Trade Agreement (FTA), which dealt with numerous provincial jurisdictions. Though provincial demands for full representation were rejected by Ottawa, the federal government agreed to increased cooperation to ensure provincial support. This included: holding a first ministers’ conference every three months during negotiations; increasing meetings between provincial and federal officials; including provinces in the meetings to determine the negotiator’s mandate; and, a federal government pledge to attain provincial approval prior to obliging itself. This benefitted both levels of government; it allowed the provinces input into negotiations so as to protect their areas of jurisdictions, while assuring the federal government that the provinces would comply with FTA obligations. It is demonstrative of this balance that the federal government permitting Quebec to opt out of a side deal and make a separate treaty with the United States in recognition of its distinct pensions system.[107] This set a standard that has since been adhered to; international relations have become a de facto concurrent jurisdiction.[108] As one might expect, given the divergence of provincial interests, this relationship is not always harmonious when consensus does not exist. The softwood lumber dispute between Canada and the United States, in which provinces have raised the issue but the federal government is recognized as the sole claimant, demonstrate how acrimonious intergovernmental relations can be.[109] Furthermore, the provinces have continued to press for a more active role in treaty-making. For instance, British Columbia and Quebec have argued that provincial legislative approval should be necessary to ratify a treaty. Typically, Ottawa has rejected these demands.[110] Nonetheless, the federal government is compelled to concede to the provincial demands in the international realm. In some cases, the provinces have even taken the lead in international negotiations. For example, the negotiation of an integrated Canadian-American energy plan was led largely by Alberta.[111] Moreover, the current mechanisms in place tend to produce strong incentives to reach a consensus regarding foreign policy.[112]

Comparison of Australian and Canadian intergovernmental relations reveal that they are affected by the distribution of treaty-powers. In Australia, centralized treaty-power allows the commonwealth to approach treaties without seriously taking states’ interests into consideration. Though intergovernmental mechanisms exist to mitigate the commonwealth’s power, these remain weak as Canberra has no institutional incentive to defer to states. Canada’s treaty-powers, by contrast, ensure that both the federal government and provinces have incentives to reach a negotiated position. Although Canadian intergovernmental relations remain less formalized than in Australia, they promote the federal balance.[113]

While it is difficult to operationalize a concept such as centralization,[114] the broadening of treaty-law has the potential to unleash latent central government power in systems with centralized treaty-adopting powers.[115] In Australia, the central government can easily overrule the states.[116] Canberra can, and on several occasions has, enforced policy consensus on the states.[117] For example, it unilaterally nullified a Tasmanian statute in 1991 in order to honor a human rights treaty.[118] As Galligan notes,

the commonwealth’s expanded role in recent decades [is] due to its superiority in matters to do with foreign affairs and treaties.[119]

In effect, Canberra’s power is as broad as potential treaty subjects, and it will continue to be the sole mediator of globalization.[120] Conversely, in Canada treaty-power must be ‘pooled’.[121] The distribution of treaty-power provides strong incentives for the federal and provincial governments to find common ground regarding international obligations; if they cannot do so, they may not be able to enter international agreements bearing significant benefits.[122] As Skogstad states, “neither order of government can realize its [foreign] policy objectives without the cooperation and coordination of the other.”[123] Because both levels of government may veto treaties, it is likely that globalization will preserve Canada’s federal balance and that Canada’s experiences of globalization will continue to be mediated by both levels of government.[124] If anything, the federal balance is strengthened by globalization. For instance, prior to the 1970s the Ottawa negotiated many trade treaties, such as Autopact, which bore on the provinces, without consultation. Once areas of provincial jurisdiction were formally in treaties, intergovernmental negotiations became necessary.[125] Furthermore, the fact that the provinces have, given the opportunity to provide input, been willing to abide treaty obligations makes unnecessary to impose constraining rules on these processes of intergovernmental relations, such as the de jure veto proposed by British Columbia and Quebec.[126]

Globalization, particularly the broadening of treaties, is likely to drastically effect the political balance in federal states. However, this affect is not unidirectional and it is important to account for these differences. In systems where the central government dominates foreign policy and mediates the impact of globalization, transnational integration encourages a centripetal dynamic. Conversely, in systems where these powers are shared between governments, globalization is not likely to drastically effect, and may even enhance, the federal balance. These considerations are important because maintaining the balance between unity and diversity is central to all federations, and because federations such as Australia and Canada will continue to be faced with the challenges and opportunities of globalization.

APPENDIX

Figure 1: The causal relationship this paper seeks to explore.

| IV-1

↓ |

+ | IV-2

↓ |

= | DV

↓ |

| processes of globalization and treaty broadening | the federation’s formal distribution of treaty-powers | centralization or decentralization of the federation |

____________________________

Figure 2: Visual representation of centralized and decentralized treaty-making powers

____________________________

Figure 3: Visual representation of centralized and decentralized treat-implementing powers

____________________________

Figure 4: Matrix view of treaty-powers, regarding both treaty-making and treaty-implementing, with relevant cases placed in it.

____________________________

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Australia Legal Information Institute, “Koowarta v Bjelke-Peterson and others; Queensland v Commonwealth,” <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/AboriginalLB/1982/27.html,> [accessed February 15, 2010]

Australia Legal Information Institute, “R v Burgess [1936] HCA 52; (1936) 55 CLR 608 (10 November 1936),” <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/cth/high_ct/55clr608.html,> [accessed February 15, 2010]

Bakvis, Herman, Gerald Baier, and Douglas Brown, Contested Federalism: Certainty and Ambiguity in the Canadian Federation (Don Mills: Oxford University Press, 2009)

Bernier, Ivan, International Legal Aspects of Federalism (London: The Longman Group Limited, 1973)

ComLaw Commonwealth Law, “Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (The Constitution),” <http://www.comlaw.gov.au/comlaw/comlaw.nsf/440c19285821b109ca256f3a001d59b7/57dea3835d797364ca256f9d0078c087/$FILE/ConstitutionAct.pdf,> [accessed February 1, 2010]

Craven, Greg, “Federal Constitutions and External Relations” in Foreign Relations and Federal States, (ed.) Brian Hocking, pp 9-26 (London: Leicester University Press, 1993)

Crawford, James, “International Law and Australian Federalism: Past, Present, and Future,” in International Law and Australian Federalism, (eds.) Brian R Opeskin and Donald R Rothwell, pp 325-342 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1997)

Cyr, Hugo, Canadian Federalism and Treaty-powers: Organic Constitutionalism at Work, (Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang, 2009)

Department of Justice, “Constitution Acts, 1867 to 1982: IX Miscellaneous Provisions, General,” < http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/Const/5.html,> (accessed February 20, 2010]

Dupras, Daniel, “International Treaties: Canadian Practice (PRB OO-O4E),” (n.m.: Government of Canada Depository Services Program, 2000), <http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/Collection-R/LoPBdP/BP/prb0004-e.htm#A.%C2%A0Authority%20Respecting%20International%20Treaties(txt),> [accessed February 20, 2010]

Fry, Earl H, “Federalism and the Evolving Cross-Border Role of Provincial, State, and Municipal Governments,” in International Journal 60, 2 (2005): 471-481

Galligan, Brian and Ben Rimmer, “The Political Dimensions of International Law in Australia,” in International Law and Australian Federalism, (eds.) Brian R Opeskin and Donald R Rothwell, pp 306-324 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1997)

Galligan, Brian, “The Centralizing and Decentralizing Effects of Globalization in Australian Federalism: Toward a New Balance,” in The Impact of Global and Regional Integration on Federal Systems: A Comparative Analysis, (eds.) Harvey Lazar, Hamish Telford, and Ronald L Watts, pp 87-122 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003)

Ghosh, Ramesh Chandra, Treaties and Federal Constitutions: Their Mutual Impact (Calcutta: The World Press Private Limited, 1961)

Ginsburg, Tom, “International Delegation and State Disaggregation,” in Constitutional Political Economy 20 (2009): 323-340

Hocking, Brian, “Introduction” in Foreign Relations and Federal States, (ed.) Brian Hocking, pp 1-8 (London: Leicester University Press, 1993)

Hogg, Peter W, Constitutional Law of Canada, Fifth Edition Supplemented, Volume 1, (Toronto: Carswell Thomson Reuters, 2007)

Hollid, Duncan B, “Why State Consent Still Matters: Non-State Actors, Treaties, and the Changing Sources of International Law,” in Berkeley Journal of International Law 23, 1 (1005): 137-174

Jennings, Mark, “Treaties in the Global Environment: The Relationship Between Treaties and Domestic Law,” (n.m.: Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2003), <http://www.dfat.gov.au/treaties/workshops/treaties_global/jennings.html,> [accessed February 20, 2010]

Judgments of the Supreme Court of Canada, “A.G. for Ontario v. Scott, [1956] SCR 137,” < http://csc.lexum.umontreal.ca/en/1955/1956scr0-137/1956scr0-137.html,> (accessed February 20, 2010).

Keohane, Robert O, Power and Governance in a Partially Globalized World (London and New York: Routledge, 2002)

Kincaid, John, “Consumership vs. Citizenship: In There Wiggle Room for Local Regulation in the Global Economy?” in Foreign Relations and Federal States, (ed.) Brian Hocking, pp 27-47 (London: Leicester University Press, 1993)

Lantis, Jeffrey S, “Leadership Matters: International Treaty Ratification in Canada and the United States,” in The American Review of Canadian Studies 35, 3 (Autumn, 2005): 383-421

Lazar, Harvey, Hamish Telford, and Ronald L Watts, “Divergent Trajectories: The Impact of Global and Regional Integration on Federal Systems,” in The Impact of Global and Regional Integration on Federal Systems: A Comparative Analysis, (eds.) Harvey Lazar, Hamish Telford, and Ronald L Watts, pp 1-34 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003)

Lecours, Andre, “Canada,” in Foreign Relations in Federal Countries, (ed.) Hans J Michelman, pp 114-140 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009)

Little, Richard, “International Regimes,” in The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, Third Edition, (eds.) John Baylis and Steve Smith, pp 369-386 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005)

Mackenzie, NAM, “Canada and the Treaty-Making Power,” in Canadian Bar Review 15, 6 (June-July, 1937): 436-454

McGrew, Anthony, “Globalization and Global Politics,” in The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, Third Edition, (eds.) John Baylis and Steve Smith, pp 19-40 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005)

Michelman, Hans J, “Introduction,” in Foreign Relations in Federal Countries, (ed.) Hans J Michelman, pp 3-8 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009)

Michelmann, Hans J, “Federalism and International Relations in Canada and the Federal Republic of Germany,” in International Journal 41, 3 (Summer, 1986): 539-571

Opeskin, Brian R, “International Law and Federal States,” in International Law and Australian Federalism, (eds.) Brian R Opeskin and Donald R Rothwell, pp 1-33 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1997)

Reus-Smit, Christian, “International Law,” in The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, Third Edition, (eds.) John Baylis and Steve Smith, pp 349-368 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005)

Robinson, Ian, “The NAFTA, the Side-Deals, and Canadian Federalism: Constitutional Reform by Other Means?” in Canada: The State of the Federation, 1993, (eds.) Ronald L Watts and Douglas M Brown, pp 193-227 (n.m.: Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, 1993)

Shapiro, Martin and Rocco J Tresolini, American Constitutional Law, Fourth Edition (New York and London: MacMillan Publishing Company Inc. and Collier MacMillan Publishers, 1975)

Simeon, Richard, “Important? Yes. Transformative? No. North American Integration and Canadian Federalism,” in The Impact of Global and Regional Integration on Federal Systems: A Comparative Analysis, (eds.) Harvey Lazar, Hamish Telford, and Ronald L Watts, pp 125-172 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003)

Skogstad, Grace, “Canadian Federalism, International Trade, and Regional Market Integration in an Era of Complex Sovereignty,” in Canadian Federalism: Performance, Effectiveness and, Legitimacy, Second Edition, (eds.) Herman Bakvis and Grace Skogstad, pp 223-245 (Don Mills: Oxford University Press, 2008)

Twomey, Anne, “Commonwealth of Australia,” in Foreign Relations in Federal Countries, (ed.) Hans J Michelman, pp 37-64 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009)

Twomey, Anne, “International Law and the Executive,” in International Law and Australian Federalism, (eds.) Brian R Opeskin and Donald R Rothwell, pp 69-103 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1997)

United Nations Treaty Collection, “Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969),” <http://untreaty.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/1_1_1969.pdf,> [accessed February 1, 2010]

Wheare, KC, Federal Government (London, New York, and Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1946)

[1] Harvey Lazar, Hamish Telford, and Ronald L Watts, “Divergent Trajectories: The Impact of Global and Regional Integration on Federal Systems,” in The Impact of Global and Regional Integration on Federal Systems: A Comparative Analysis, (eds.) Harvey Lazar, Hamish Telford, and Ronald L Watts, pp 1-34 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003), 3

[2] KC Wheare, Federal Government (London, New York, and Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1946), 187

[3] Lazar, Telford, and Watts, 22

[4] Ivan Bernier, International Legal Aspects of Federalism (London: The Longman Group Limited, 1973), 1; Brian Hocking, “Introduction” in Foreign Relations and Federal States, (ed.) Brian Hocking, pp 1-8 (London: Leicester University Press, 1993), 3-5; Lazar, Telford, and Watts, 3-4, 8, 17-18

[5] Greg Craven, “Federal Constitutions and External Relations” in Foreign Relations and Federal States, (ed.) Brian Hocking, pp 9-26 (London: Leicester University Press, 1993), 9; Lazar, Telford, and Watts, 2, 6, 18; John Kincaid, “Consumership vs. Citizenship: In There Wiggle Room for Local Regulation in the Global Economy?” in Foreign Relations and Federal States, (ed.) Brian Hocking, pp 27-47 (London: Leicester University Press, 1993), 44; Richard Simeon, “Important? Yes. Transformative? No. North American Integration and Canadian Federalism,” in The Impact of Global and Regional Integration on Federal Systems: A Comparative Analysis, (eds.) Harvey Lazar, Hamish Telford, and Ronald L Watts, pp 125-172 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003), 146, 150; Ian Robinson, “The NAFTA, the Side-Deals, and Canadian Federalism: Constitutional Reform by Other Means?” in Canada: The State of the Federation, 1993, (eds.) Ronald L Watts and Douglas M Brown, pp 193-227 (n.m.: Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, 1993), 217; Hans J Michelmann, “Introduction,” in Foreign Relations in Federal Countries, (ed.) Hans J Michelmann, pp 3-8 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009), 3; Brian R Opeskin, “International Law and Federal States,” in International Law and Australian Federalism, (eds.) Brian R Opeskin and Donald R Rothwell, pp 1-33 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1997), 1; Brian Galligan and Ben Rimmer, “The Political Dimensions of International Law in Australia,” in International Law and Australian Federalism, (eds.) Brian R Opeskin and Donald R Rothwell, pp 306-324 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1997), 312, 314

[6] Brian Galligan, “The Centralizing and Decentralizing Effects of Globalization in Australian Federalism: Toward a New Balance,” in The Impact of Global and Regional Integration on Federal Systems: A Comparative Analysis, (eds.) Harvey Lazar, Hamish Telford, and Ronald L Watts, pp 87-122 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003), 88

[7] Robert O Keohane, Power and Governance in a Partially Globalized World (London and New York: Routledge, 2002), 15; Anthony McGrew, “Globalization and Global Politics,” in The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, Third Edition, (eds.) John Baylis and Steve Smith, pp 19-40 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 24; Galligan, 88; Lazar, Telford, and Watts, 3; Earl H Fry, “Federalism and the Evolving Cross-Border Role of Provincial, State, and Municipal Governments,” in International Journal 60, 2 (2005): 472-473

[8] Michelmann (2009), 4-6; Galligan and Rimmer, 313

[9] Lazar, Telford, and Watts, 3; also see, Bernier, 1; Hugo Cyr, Canadian Federalism and Treaty-powers: Organic Constitutionalism at Work, (Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang, 2009), 186-196, 201; Tom Ginsburg, “International Delegation and State Disaggregation,” in Constitutional Political Economy 20 (2009): 334; Hocking, 3

[10] Kincaid, 28, 35-36; Cyr, 201; Lazar, Telford, and Watts, 5; Hocking, 5; Simeon, 150; Christian Reus-Smit, “International Law,” in The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, Third Edition, (eds.) John Baylis and Steve Smith, pp 349-368 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 358; Grace Skogstad, “Canadian Federalism, International Trade, and Regional Market Integration in an Era of Complex,” in Canadian Federalism: Performance, Effectiveness, and Legitimacy, Second Edition, (eds.) Herman Bakvis and Grace Skogstad, pp 223-245 (Don Mills: Oxford University Press, 2008), 223

[11] Cyr, 202; Peter W Hogg, Constitutional Law of Canada, Fifth Edition Supplemented, Volume 1, (Toronto: Carswell Thomson Reuters, 2007), 11.4; Ginsburg, 326-327; Jeffrey S Lantis, “Leadership Matters: International Treaty Ratification in Canada and the United States,” in The American Review of Canadian Studies 35, 3 (Autumn, 2005): 384-385; Reus-Smit, 361; Richard Little, “International Regimes,” in The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, Third Edition, (eds.) John Baylis and Steve Smith, pp 369-386 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 377-380

[12] Cyr, 235-236; Reus-Smit, 362; Ginsburg, 325; Duncan B Hollis, “Why State Consent Still Matters: Non-State Actors, Treaties, and the Changing Sources of International Law,” in Berkeley Journal of International Law 23, 1 (1005): 141

[13] Hogg, 11.5;

[14] Bernier, 150; also see, Michelmann (2009), 3

[15] Hogg, 11.9

[16] Reus-Smit, 355-357; Hollis, 142, 145

[17] Hogg, 11.2; Bernier, 13; Reus-Smit, 358

[18] Bernier, 120

[19] United Nations Treaty Collection, “Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969),” <http://untreaty.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/1_1_1969.pdf,> [accessed February 1, 2010], 11; Opeskin, 5; Bernier, 1; Ramesh Chandra Ghosh, Treaties and Federal Constitutions: Their Mutual Impact (Calcutta: The World Press Private Limited, 1961), 292

[20] Ghosh, 292; also see Opeskin, 4

[21] Michelmann (2009), 6; Craven, 10, 23

[22] Bernier, 120, 269, 271; Lazar, Telford, and Watts, 4; Hocking, 1-2; Cyr, 160-161; Craven, 12

[23] Wheare, 178; Craven, 16; Bernier, 13-14, 47-48; Ghosh, 294-295; Hollis, 146, 148-150

[24] Craven, 18; Hans J Michelmann “Federalism and International Relations in Canada and the Federal Republic of Germany,” in International Journal 41, 3 (Summer, 1986), 551

[25] Wheare, 196; Craven, 10; Ghosh, 295; Michelmann (2009), 3, 6; Cyr, 159

[26] Bernier, 50, 120; Wheare, 187; Hollis, 154-155; Opeskin, 6; Ghosh, 295

[27] United Nations Treaty Collection, 11, 17; Bernier, 15-16

[28] Simeon, 151; Anne Twomey, “Commonwealth of Australia,” in Foreign Relations in Federal Countries, (ed.) Hans J Michelman, pp 37-64 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009), 51

[29] Bernier, 171; Opeskin, 13-19

[30] Skogstad, 226-227

[31] Bernier, 173

[32] James Crawford, “International Law and Australian Federalism: Past, Present, and Future,” in International Law and Australian Federalism, (eds.) Brian R Opeskin and Donald R Rothwell, pp 325-342 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1997), 334; Skogstad, 226

[33] Opeskin, 6

[34] Hogg, 11.5; Craven, 10-11; Wheare, 179

[35] Craven, 11 Ginsburg, 331

[36] Bernier, 47; Wheare, 181, 184; Hogg, 11.6; Ghosh, 299; Craven, 15; NAM Mackenzie, “Canada and the Treaty-Making Power,” in Canadian Bar Review 15, 6 (June-July, 1937) 444

[37] Shaprio and Tresolini, 144-146, 171-172, 187-190, ; Bernier, 160; Hogg, 11.10; Ginsburg, 323

[38] Martin Shapiro and Rocco J Tresolini, American Constitutional Law, Fourth Edition (New York and London: MacMillan Publishing Company Inc. and Collier MacMillan Publishers, 1975), 171; Craven, 15, 23; Wheare, 181, 190; Ghosh, 296; Lantis, 385

[39] Michelmann (1986), 543-544; Craven, 17

[40] Craven, 13, 17, 23; Michelmann (1986), 542-545

[41] Bernier, 149

[42] Bernier, 149

[43] Simeon, 154; Lecours, 123; Wheare, 186-187; Craven, 9, 109; Ghosh, 298-299

[44] Michelmann (1986), 543; Craven, 10, 18-19, 24; Ghosh, 301;

[45] Lazar, Telford, and Watts, 11; Michelmann (2009), 7; Galligan, 94, 116; Michelmann (1986), 541

[46] Craven, 23; Michelmann (2009), 6-7; Opeskin, 2; Galligan, 89; Lazar, Telford, and Watts, 15, 17; Twomey (2009), 43; Simeon, 128, 146, 152

[47] Lazar, Telford and Watts, 15;

[48] Twomey (2009), 38-39; Galligan, 89

[49] Galligan, 89, 101, 108, 114

[50] Galligan, 93-94; Craven, 13; Simeon, 136

[51] Wheare, 183; Mark Jennings, “Treaties in the Global Environment: The Relationship Between Treaties and Domestic Law,” (n.m.: Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2003), <http://www.dfat.gov.au/treaties/workshops/treaties_global/jennings.html,> [accessed February 20, 2010]; Twomey (2009), 40; Anne Twomey, “International Law and the Executive,” in International Law and Australian Federalism, (eds.) Brian R Opeskin and Donald R Rothwell, pp 69-103 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1997), 84; Hogg, 11.5; Lantis, 385; Mackenzie, 441; Craven, 14

[52] Craven, 13, 18, 19; Twomey (2009), 40; Hogg, 11.6

[53] ComLaw Commonwealth Law, “Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (The Constitution),” <http://www.comlaw.gov.au/comlaw/comlaw.nsf/440c19285821b109ca256f3a001d59b7/57dea3835d797364ca256f9d0078c087/$FILE/ConstitutionAct.pdf,> [accessed February 1, 2010], 18-19; Craven, 19; Ghosh, 294; Galligan, 96

[54] Twomey (2009), 40; Bernier, 168; Craven, 19-21, 23; Twomey (1997), 79; Ghosh, 301; Crawford, 331; Galligan and Rimmer, 307; Galligan, 98

[55] Craven, 21; Twomey (2009), 40; Opeskin, 10; Twomey (1997), 44, 76-77

[56] Galligan, 93; Craven, 21; Hogg, 11.10-11.11

[57] Australia Legal Information Institute, “R v Burgess [1936] HCA 52; (1936) 55 CLR 608 (10 November 1936),” <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/cth/high_ct/55clr608.html,> [accessed February 15, 2010]; also see; Wheare, 183; Galligan, 93

[58] Galligan, 97; Hogg, 11.10

[59] Craven, 21; Galligan, 97; Twomey (2009), 37, 40; Hogg, 11.11; Australia Legal Information Institute, “Koowarta v Bjelke-Peterson and others; Queensland v Commonwealth,” <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/AboriginalLB/1982/27.html,> [accessed February 15, 2010]; Crawford, 330; Galligan and Rimmer, 337

[60] Galligan, 97; also see, Australia Legal Information Institute, “Koowarta v Bjelke-Peterson and others; Queensland v Commonwealth”; Crawford, 331

[61] Crawford, 332-333

[62] Crawford, 333

[63] Twomey (2009), 43; Crawford, 32

[64] Twomey (2009), 44-45, 58

[65] Galligan and Rimmer, 315; Twomey (2009), 50

[66] Twomey (2009), 37, 52-53; Crawford, 333; Opeskin, 2; Galligan, 98, 115, 119; Lazar, Telford, and Watts, 15; Margaret Allars, “Internal Law and Administrative Discretion,” in International Law and Australian Federalism, (eds.) Brian R Opeskin and Donald R Rothwell, pp 232-279 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1997), 35; Galligan and Rimmer, 308, 314

[67] Galligan, 89, 99, 108-109, 119; Twomey (2009), 46; Galligan and Rimmer, 314

[68] Twomey (2009), 46-47; Craven, 22;

[69] Crawford, 336; Twomey (2009), 47-48; Galligan, 98; Twomey (197), 82

[70] Galligan, 113

[71] Twomey, (2009), 49

[72] Twomey (2009), 47; Twomey (1997), 81, 82

[73] Galligan, 113

[74] Galligan, 113; Twomey (2009), 47

[75] Twomey (2009), 47, 49

[76] Crawford, 36-337; Opeskin, 2

[77] Michelmann (1986), 539; Simeon, 125, 132-133; Fry, 472-475; Skogstad, 229

[78] Hogg, 11.17; Simeon, 131; Robinson, 205

[79] Simeon, 131, 137-138; Andre Lecours, “Canada,” in Foreign Relations in Federal Countries, (ed.) Hans J Michelman, pp 114-140 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009), 117, 119; Michelmann (1986), 540, 542, 548, 561

[80] Michelmann (1986), 555; also see, Craven, 13, 15; Hogg, 11.2; Mackenzie, 437; Cyr, 221

[81] Hogg, 11.2, 11,12; Wheare, 184; Michelmann (1986), 543; Lecours, 120

[82] Craven, 14; Cyr, 105-106; Hogg, 11.2; Michelmann (1986), 548; Wheare, 193

[83] Hogg, 11.2-11.3, 11.19; Bernier, 52; Michelmann (1986), 540, 549; Craven, 14-15; Lecours, 115

[84] Bernier, 52, 56; Hogg, 11.19-11.20

[85] Daniel Dupras, “International Treaties: Canadian Practice (PRB OO-O4E),” (n.m.: Government of Canada Depository Services Program, 2000), <http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/Collection-R/LoPBdP/BP/prb0004-e.htm#A.%C2%A0Authority%20Respecting%20International%20Treaties(txt),> [accessed February 20, 2010]; also see, Michelmann (1986), 548

[86] Ghosh, 294; Hogg, 11.19-11.20

[87] Bernier, 57-60; Hollis, 150; Judgments of the Supreme Court of Canada, “A.G. for Ontario v. Scott, [1956] SCR 137,” <http://csc.lexum.umontreal.ca/en/1955/1956scr0-137/1956scr0-137.html,> (accessed February 20, 2010).

[88] Hollis, 148, 151

[89] Hogg, 11.19; Michelmann (1986), 556, 562; Cyr, 208-209, 239

[90] Lazar, Telford, and Watts, 17; Bernier, 54; Craven, 14

[91] Department of Justice, “Constitution Acts, 1867 to 1982: IX Miscellaneous Provisions, General,” <http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/Const/5.html,> [accessed February 20, 2010]; also see Hogg, 11.11; Bernier, 51, Mackenzie, 438

[92] Bernier, 52, 154; Wheare, 184-185; Craven, 14; Craven, 14; Simeon, 135; Lecours, 120-121; Hogg, 11.12-11.14; Mckenzie, 436, 438; Fry, 475; Skogstad, 226

[93] Wheare, 185; Craven, 14-15; Ghosh, 302

[94] Hogg, 11.9; also see Mackenzie, 441; Bernier, 6-7; Lantis, 385

[95] Robinson, 212; Cyr, 217, 223-226, 228; Hogg, 11.15

[96] Simeon, 134-135; Robinson, 212-214; Skogstad, 227

[97] Hogg, 11.17; Cyr, 228-235; Simeon, 150; Michelmann (1986), 548; Robinson, 210-211, 214

[98] Bernier, 154-155

[99] Simeon, 156; Bernier, 154-155; Skogstad, 226

[100] Lecours, 121-122; Michelmann (1986), 540-541, 548, 549; Cyr, 211; Michelmann (2009), 124; Simeon, 156

[101] Lantis, 395-396

[102] Robinson, 215; Herman Bakvis, Gerald Baier, and Douglas Brown, Contested Federalism: Certainty and Ambiguity in the Canadian Federation (Don Mills: Oxford University Press, 2009), 178

[103] Cyr, 214; Wheare 186; Lecours, 115; Hogg, 11.16

[104] Simeon, 135

[105] Cyr, 211; Bernier, 237

[106] Michelmann (1986), 555, 558; Cyr, 211; Michelmann (2009), 121-122; Bernier, 271-272; Simeon, 137, 152-153; Lecours, 122-123

[107] Lecours, 119, 123; Simeon, 155

[108] Skogstad, 227; Lecours, 124

[109] Lecours, 119; Skogstad, 230-233

[110] Skogstad, 235-236

[111] Simeon, 157

[112] Skogstad, 236-237

[113] Lazar, Telford, Watts, 11

[114] Simeon, 146

[115] Bernier, 1; Craven, 11, 22; Hogg, 11.16-11.17; Crawford, 332; Galligan and Rimmer, 314, 321; Cyr, 236-237; Ginsburg, 324, 335; Galligan, 110, 119; Lazar, Telford, and Watts, 15

[116] Lazar, Telford, and Watts, 17; Galligan, 110-111; Craven, 22-23; Kincaid, 37-38

[117] Crawford, 331; Galligan, 97; Twomey (2009), 51

[118] Twomey (2009), 51

[119] Galligan, 119; also see, Lazar, Telford and Watts, 15

[120] Crawford, 332; Galligan, 96; Twomey (2009), 44

[121] Skogstad, 230

[122] Opeskin, 5; Cyr, 162; Hogg, 11.16

[123] Skogstad, 240

[124] Simeon, 152, 162

[125] Lecours, 123

[126] Skogstad, 237

—

Written by: Ryan Morrow

Written at: University of Toronto

Written for: Professor Michael Stein

Date: 2010

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Casting Light on EU Governance: Reflection and Foresight in an Era of Crises

- Protecting the Defenders: Exploring the Role of Global Corporations and Treaties

- A New Era of UN Peacekeeping? The Women, Peace and Security Agenda in Africa

- Cosmological Politics: Towards a Planetary Balance of Power for the Anthropocene

- Integrating under Threat: A Balance-of-threat Account of European Integration

- Everyday (In)Security: An Autoethnography of Student Life in the UK