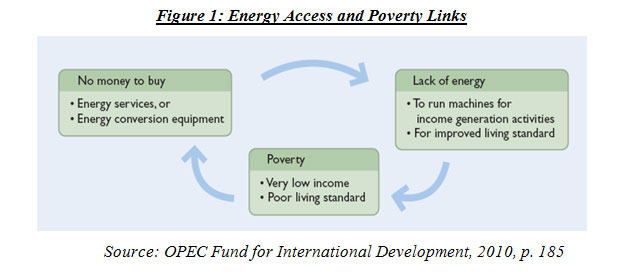

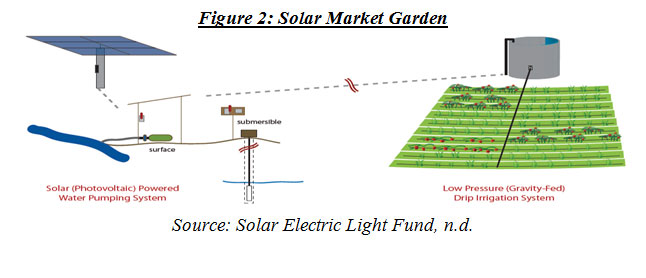

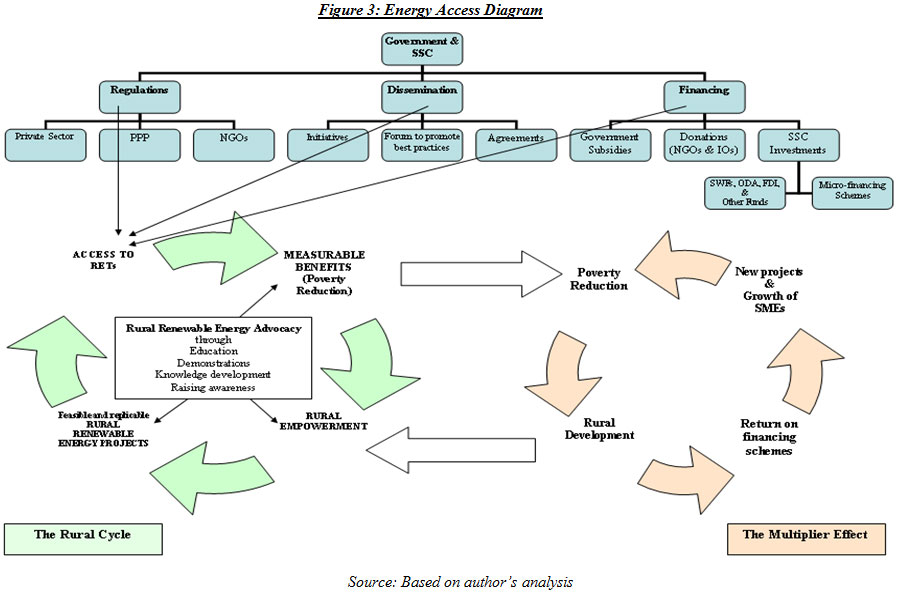

At the root of poverty, lies a lack of access to modern energy. Without energy in rural areas, clinics cannot operate, agriculture is plagued by inefficiencies, schools cannot be lit, and opportunities to generate additional income are easily lost. In fact, most of the Millennium Development Goals cannot be fulfilled without first meeting the energy needs of the 1.6 billion people without access to modern energy services. Unfortunately, these people live in areas far from the electric grid. Thus, decentralized energy systems represent the best options to generate access. Many sustainable projects have been implemented to address energy poverty in rural areas; however their success has not been easily replicated. The Solar Market Garden project, lead by Solar Electric Light Fund, has demonstrated notorious success in Northern Benin; this project clearly meets the criteria for replication in other areas. Emerging South-South Cooperation initiatives and programmes of action may easily address this problem of replication. Several key requirements must be met for South-South Cooperation to successfully implement a programme of action, which addresses energy poverty in rural areas. These requirements are regulations, which promote local initiatives and trade in renewable energy technologies; financing mechanisms, which encourage local investments and promote rural markets; and dissemination, which improve knowledge of these technologies and their benefits for rural areas. In addition, advocacy strategies implemented by non-governmental organizations and South-South Cooperation forums will raise awareness of these rural renewable energy technologies and their value for local communities. Furthermore, local partnerships with experts and with the communities themselves aid the successful replication of any rural renewable energy project. The value of renewable energy in addressing energy poverty should not be underestimated; thus, the established Energy Access diagram encompasses various elements from access to renewable energy technologies to dissemination, regulation, financing mechanisms, and the promotion of local entrepreneurship.

Chapter 1: Defining a Path

1.1 INTRODUCTION

A world without poverty, where ¼ of the world’s population (Chen & Ravallion, 2008, p. 30) living in conditions of hardship and scarcity have access to internet, mobiles, a heated home, food, clean water, and many other items, which are taken for granted in the developed world, might not be possible in the foreseeable future for this ¼ of the world’s population. However, actions can and must be taken to empower these populations to improve their living standards.

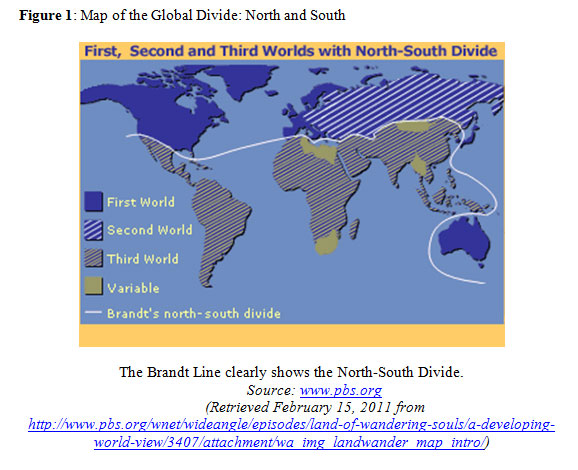

Since the Independent Commission on International Development Issues in Germany released the Brandt Report in the 1980, the world has been depicted as divided into a global North and a global South (Quilligan, 2002)[1]. Today, this division cuts through a clear developmental, wealth, and digital gap. The global North includes North America (Canada and the United States), Europe, Russia, Australia, and New Zealand. The South encompasses about 130 countries and includes all the developing nations from the emerging economies of Brazil, India, and China to the least developed countries (LDCs) like Nepal and Bangladesh. According to a United Nations (UN) report for the General Assembly, “the world population of over 6 billion people [is divided] into a two-thirds majority of poor people, living mostly in Africa, Asia and Latin America, and an affluent one third, living mostly in the industrialized societies of Europe, North America and parts of Australasia” (2009, p. 22). These two-thirds majority can be found in the global South, where various factors have hindered equitable and sustained development and the needs of the poor have not been generally addressed.

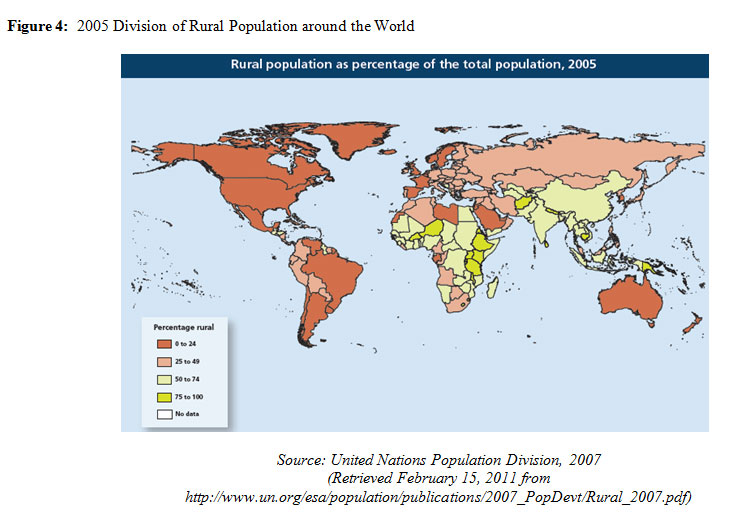

Rural populations accounted for “about 3.4 billion persons in 2005, slightly over half of the global population. Over 90 per cent of the world’s rural residents (3.0 billion) live in the less developed regions” (U.N. Population Division, 2008b, p. 2). Hence this lead to the creation of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in the year 2000; the first goal declares that by 2015 the people living in poverty should be halved (U.N. Department of Public Information, 2010). Efforts have been underway with mixed degrees of success. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), governments, international organizations, and corporations have all implemented programmes for poverty reduction and for achieving the other MDGs. The large scale of these goals seems insurmountable, yet small steps have been achieved and it is these small, yet significant, successes which must be recognized, applauded, and replicated.

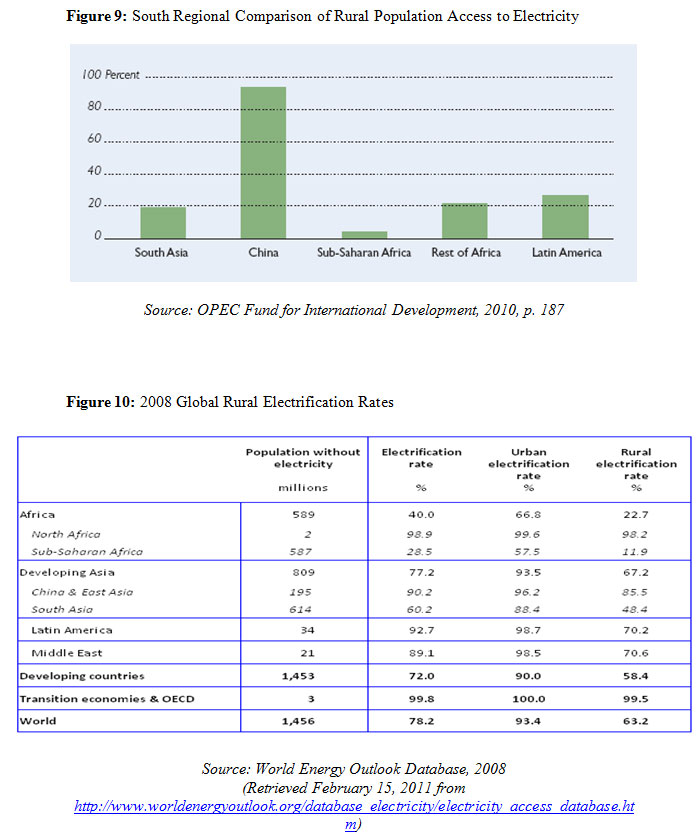

Nevertheless in many instances a lack of financing combined with a lack of global awareness prevents knowledge of these small successful projects from large-scale replication in other parts of the world. Initiative and innovation exist throughout the globe; however economic conditions hinder these movements and projects. Addressing energy poverty in rural areas represents the basis by which the MDGs may be reached, sustainable development may be addressed, and the economic development of a nation may progress in a more equitable manner. Figure 9 in the annex provides a regional comparison of electricity access in the global South; as can be noted, most of the South’s rural populations (with the exception of China) have limited or no access to electricity. In fact, rural electrification rates are below 20% for these areas.

Without electricity, clinics cannot function, students cannot study, entrepreneurship is stifled, and income cannot be generated in an efficient and effective manner. Energy poverty must be addressed if the MDGs are to succeed and if rural development is to take place. The reemergence of South-South cooperation (SSC) in the last decade provides the necessary forum by which specific development strategies can be implemented to address energy poverty in rural areas of the global South. Thus, SSC is key to the success of the MDGs and for the South to catch up with the North.

1.1.2 What is South-South Cooperation?

SSC can be defined as an exchange of resources, knowledge, and technology among nations of the global South, which consider themselves equals. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) defines it as:

a process whereby two or more developing countries pursue their individual or collective development through cooperative exchange of knowledge, skills, resources and technical expertise. […] South-South Cooperation is multidimensional in scope and can include all sectors and kinds of cooperation activities among developing countries, whether bilateral or multilateral, subregional, regional or interregional. (2007, p. 1)

Its goal is to achieve the same development status as the global North. The emerging BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) economies are spearheading this movement forward by forging the path towards which the remaining Southern nations can begin to achieve the same levels of economic growth. Unfortunately, economic growth and higher income per capita do not automatically create conditions for equitable development. It is in this area where SSC can play a larger role and ensure rural development.

1.1.3 The Importance of Rural Development

In this respect, SSC can potentially provide the means and the impetus for the South to take full ownership over their own development plans and can ensure equitable and sustainable development for both urban and rural areas. Unfortunately, these latter areas do not always receive the necessary attention as urban areas’ continued growth and expansion demand the attention of the government. In fact, large cities are perceived as a sign of development with access to the most essential resources like water, goods, technology, and income, to name a few. However, sprawling, steadily growing cities are a cause of rural underdevelopment. “Urbanization has been driven by the concentration of investment and employment opportunities in urban areas as well as by the transition from low-productivity agriculture to more productive mechanized agriculture that has produced labour surpluses in rural areas” (U.N. Population Division, 2008a, p. 3). Thus, these areas face a double challenge: one of inherent underdevelopment and the other of labour and innovation migrating away from these areas.

Both challenges are clearly interconnected. Their importance is reflected in the growing literature and the establishment of various projects, programmes, and policies addressing rural development. Yet, governmental resources have not been completely oriented towards these underdeveloped rural areas. “Because of economies of scale, it is more efficient and cheaper to provide such services [employment, transportation, water supply, health, etc] to large and geographically concentrated populations than to populations scattered over large rural areas” (U.N. Population Division, 2008a, p. 4). Urban areas due to their large population numbers demand more governmental attention than rural areas, whose populations numbers are generally small, comparatively speaking.

1.1.4 What is Energy Poverty?

A key component for rural development is addressing the lack of access to energy resources and improving the access to sustainable energy sources. A Washington DC-based NGO, Solar Electric Light Fund (SELF), defines energy poverty “as a lack of access to clean and efficient energy systems” (Solar Electric Light Fund, 2011a). Access to financing, technologies, and training is a key requirement that would permit rural areas to achieve sustainable development. One of UNDP’s focus areas reinforces:

energy [as] central to sustainable development and poverty reduction efforts. It affects all aspects of development — social, economic, and environmental – including livelihoods, access to water, agricultural productivity, health, population levels, education, and gender-related issues. None of the MDGs can be met without major improvement in the quality and quantity of energy services in developing countries. (UNDP, 2011)

Many studies have been completed to analyze rural development and energy poverty. However, specific strategies that place SSC, as a forum through which a developmental framework may be created to address rural development and energy poverty within the global South itself, have not necessarily established the best approach to address the replication of small-scale projects under the umbrella of SSC.

Sustainable development was officially defined in 1987 by the UN World Commission on Environment and Development, known as the Brutland Commission, as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (United Nations, 1987, art. 1). In rural areas around the developing South, projects and programmes established to aid their development have generally met immediate needs and implemented activities based on current practices, which are not always sustainable for the long run. However, many projects such as the Alleviation of Poverty through the Provision of Local Energy Services (APPLES) programme have a stated goal “to find a sustainable mechanism for the effective delivery of improved local energy services to poor communities in South Africa” (APPLES, 2009, p. 6). Such objectives fit the Brutland Commission’s sustainable development paradigm to meet future needs and contribute to environmental sustainability.

It is not just about addressing energy poverty; it is about addressing it in a sustainable manner.

1.1.5 Energy Poverty and Sustainability

Shifting from unsustainable practices into sustainable ones is not always clearly achieved. However, beginning with sustainable practices sets a norm for future practices. Thus, a clear opportunity exists for renewable, clean sources of energy to be employed, specifically for those without energy access:

More than a quarter of the world’s population, mostly in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, suffers from acute energy poverty with no access to electricity. In India alone, 600 million people—roughly half the population—are off the electric grid. Hundreds of millions suffer chronic power outages due to an unreliable electricity system. In addition, roughly 40 percent of the world population still relies on traditional wood, crop residues and animal waste as their main cooking and heating fuels. Clearly for this half of humanity the meaning of energy security is different from that of the developed world. (Luft & Korin, 2009, p. 5)

Most of these areas lack access to electric grids. The costs of extending these grids are insurmountable. Solar power, hydropower, and wind power exemplify sustainable energy practices[2], which are renewable and ensure that the needs of both the future and the present are met.

Most renewable energy systems are generally decentralized and hence do not need to rely on the extension of grids for their implementation. Electricity “allows individuals to extend the length of time spent on production and hence on income producing activities. It also allows children time to read or do homework and access to television and film, which opens rural residents to new information that can instill the idea of change and the potential for self-improvement” (Baker Institute Energy Forum[3], n.d.). Without energy, human progress and development stalls in both the short and most importantly, the long term. Its effects transcend beyond the immediate community and affect overall national and regional development.

1.1.6 Electricity and Rural Development Linkages

Energy usage is generally evident in two main sectors: transportation and power generation (electricity). The focus of this study will be on this latter aspect of energy. The U.S. Energy Information Administration defines electricity as “the flow of electrical power or charge […] Electricity is actually a secondary energy source, also referred to as an energy carrier. That means that we get electricity from the conversion of other sources of energy, such as coal, nuclear, or solar energy” (2010a). Electricity can be generated by both renewable (for example solar, wind, geothermal, and hydropower) and non-renewable (for example coal, oil, and natural gas) sources of energy.

Renewable sources, as implied by the word, cannot be exhausted. On the other hand, non-renewable sources generally originate from fossil fuels. Oil, natural gas, and coal have a time stamp on them. They are also the types of sources that emit greenhouse gases and are not environmentally friendly. “Throughout the world today electricity is generated from coal (41%), natural gas (20.5%), renewable like hydroelectric, biomass, solar, wind and geothermal power (18.5%) and nuclear power (15%) […] Only 5% of world electricity is made from petroleum” (Luft & Korin, 2009, p. 6).

Climate change discourse today focuses on the use of technologies that will mitigate the effects of non-renewable energy sources such as coal and oil. However, an increased usage of renewable resources has not been on the top of the agenda due to the high costs associated with their implementation and the simple fact that solar power cannot work without sun, hydropower needs strong currents of water (droughts can affect this), and wind power is based on strong wind currents.

Notwithstanding, “electricity generation is entering a period of transformation as investment shifts to low-carbon technologies—the result of higher fossil-fuel process and government policies to enhance energy security and to curb emissions of CO2” (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development/International Energy Agency [OECD/IEA], 2010, p. 8). The global community seeks changes to the manner in which electricity is generated, however many rural areas still have no access to electricity. This in turn has generated a natural process of rural-urban migration. In many instances, “urbanization becomes a problem when urban population growth exceeds the growth of employment or of housing, infrastructure and services. In that case, the growing urban population can find neither work nor housing, and rural-to-urban migration leads only to the urbanization of poverty” (Sheng, 2003, p. 143). Thus, it is imperative for governmental policies to address both urban and rural growth. Addressing rural development through the provision of electricity would affect urban development in a positive manner through the alleviation of migratory pressures.

Unfortunately, geopolitical and economic concerns sometimes prevent and hinder electricity provision in these rural areas. “Energy security means different things to different countries based on their geographical location, their geological endowment, their international relations, their political system, and their economic disposition” (Luft & Korin, 2009, p. 5). Exporters of energy seek demand guarantees, while importers of energy seek guarantees of supply. The focus of this study is on the energy security of rural areas, of those 1.6 billion people who lack access to electricity and of those 2.4 billion people who still rely on biomass (wood, dung, agricultural residues, etc), which causes health problems (Baker Institute Energy Forum, n.d.). In many parts of the rural South, electricity usage is not as high as it would be in the North, where air conditioning, refrigeration, and other residential uses utilize a high portion of electricity.

In rural areas, “the most common uses of electricity are lighting and television, and there is some resistance to using electricity for cooking” (The World Bank Group, 2011a). Simple, basic uses that can make a world of difference in their lives; just lightning alone allows young children to study after the sun goes down and for parents to expand their ability to work from home or access information through the television or computers that can improve their living standards.

Electricity can be measured in units of power known as watts and kilowatts. “A kilowatthour (kWh) is equal to the energy of 1,000 watts working for one hour” (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2010b). In rural areas, unlike urban areas, electricity use is minimal. Unfortunately, electric grid extensions do not reach these areas due to high costs and a policy focus on urban areas. Fortunately, rural energy development has been addressed in many forms by various NGOs and international organizations, which have succeeded in many of their projects as is the case with SELF. In the project of Benin, this NGO installed

an innovative solar-powered drip irrigation system to pump water for food crops. [… As a consequence,] not only are the women better fed, but so are the children and the rest of the villagers who now have year-round access to a steady supply of highly nutritious fruits and vegetables. (SELF, n.d)

The success of SELF will be replicated in another 8 villages in Benin. In view of its achievement, it would seem only natural that its replication by other organizations, governments, and various international entities would follow. Unfortunately, many of these sustainable projects do not always transform into larger scale projects that could affect the overall rural development of a nation or of a region.

1.1.7 Purpose of this Study: SSC-Energy Poverty Linkage

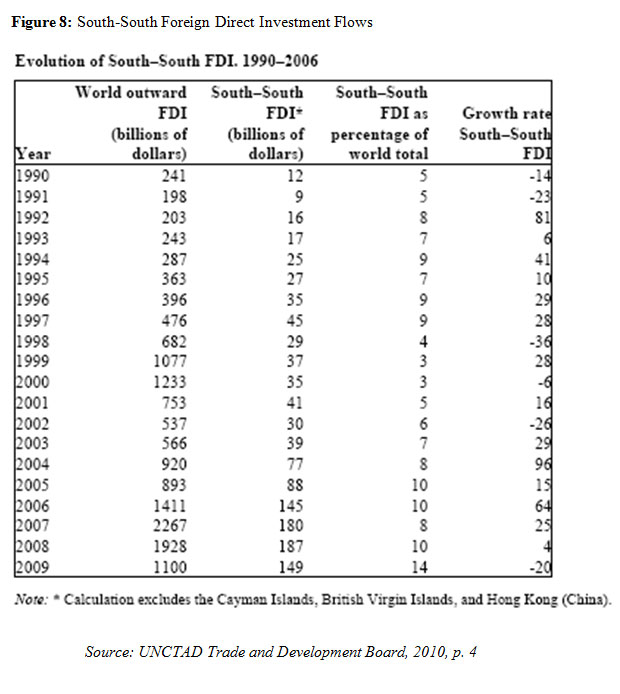

With 1.6 billion inhabitants without electricity, international, regional, and national priorities should clearly emphasize the replication of such projects, which address energy poverty in a sustainable manner. 90% of these rural residents reside in the South. Thus, it only seems natural that SSC represents the movement through which replication of successful renewable energy projects can be achieved in these areas. Specific development strategies need to be elaborated, which are applicable on a local, national, sub-regional, regional, and global level. However, SSC takes on many forms; in fact, many initiatives can be considered a part of SSC, from regional bodies such as the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) and the African Union (AU) to numerous bilateral agreements between Southern nations. Foreign direct investment (FDI), sovereign wealth fund (SWFs) investments, and development assistance amongst Southern nations also falls under this category.

In recent years, SSC has also evolved to include the North in many of its initiatives: triangular cooperation can be defined “as partnerships between [Northern] donors and pivotal countries (providers of South-South Cooperation) to implement development cooperation programmes/projects in beneficiary countries (recipients of development aid)” (Fordelone, 2009, p. 4). Triangular cooperation allows for the best of both worlds: North and South. The global North provides expertise and financing, while the global South contributes financing in addition to technologies and above all an understanding of common developmental challenges. A UNDP study showed that:

what makes Brazilian cooperation stand out and in fact prove more effective than traditional North-South cooperation is that it owns current technology that developed, ‘Northern’ countries do not have, as they no longer face those issues – and if they once had it, it has now become obsolete, or the institutional memory has been lost. (UNDP, 2009, p. 64)

Herein lies the future success of SSC development strategies and its potential contribution towards addressing energy poverty in rural areas of the developing world.

The purpose of this study will be to establish development strategies applicable to local rural contexts for international, regional, and national entities under the SSC umbrella with the goal of promoting, implementing, and replicating rural renewable energy projects. Many small projects sponsored by NGOs have proven their value in addressing energy poverty on a small, local scale. Moving forward, it will be imperative for these projects to become applicable on a larger scale, so that other rural areas may benefit from these advancements and further their development prospects.

The goal of this study is to determine the best mechanisms in which small-scale, successful projects may be replicated in other rural areas of the global South. Thus, the three main objectives of this research will be:

- To demonstrate successful cases of sustainable energy development within rural areas of the global South;

- Examine SSC policies on a subregional, regional, and international scale; and finally

- Recommend SSC development strategies to address energy poverty in rural areas and empower both national and local initiatives.

This study will also explore renewable energy technologies (RETs) as a means towards achieving rural development. Standard electric grid extensions are accessible to few rural villages as proximity to urban areas is a requirement for their expansion. High costs associated with their extension also hinder access to these grids. Decentralized, non-grid electric systems represent the best alternative for rural villages to access electricity and begin to improve their daily lives. “Poverty remains largely a rural problem, and a majority of the world’s poor will live in rural areas for many decades to come” (International Fund for Agricultural Development [IFAD], 2010, p. 47). Rural development is therefore crucial for the well-balanced development of a nation.

Access to electricity, a resource often taken for granted in the developed world, will allow for rural residents to access education, income, food, and clean water. “Now and for the foreseeable future, it is thus critical to direct greater attention and resources to creating new economic opportunities in the rural areas for tomorrow’s generations” (IFAD, 2010, p. 70). Currently, a great opportunity exists for rural development strategies to adapt sustainable measures to ensure that the needs of both the present and the future are met.

Access to renewable sources of energy, which are not cost-prohibitive, is key for development to truly move forward. This research will focus on electricity as a source of energy. Its availability and access in rural areas improves livelihoods through better access to education, technology, training, and effective and efficient agricultural practices. Electricity represents the foundation through which future development projects may be implemented and through which the vicious poverty cycle might be broken. Many successful rural renewable energy access projects go unnoticed, thus the main theme behind the final recommendations for SSC development strategies is about scaling up small-scale projects and replicating them in other parts of the South.

1.2 METHODOLOGY

SSC represents quite a large movement. In addition, rural development and energy poverty are large topics. As part of the research, these three large areas were narrowed down to allow for a proper analysis to be completed and recommendations to be formulated within the allotted time frame of three months. Thus, the concept of SSC was limited to policy recommendations enacted to address sustainable development. Energy poverty was delineated according to access to electricity and not coal and oil, which is what can be commonly inferred by the term. Rural development encompasses a range of strategies and outcomes. Its focus can vary from the provision of schools and clinics to rural-urban migration strategies and agriculture and non-farm economies. Since many rural villages subsist primarily through agricultural means, a specific focus on case studies, which improved agricultural subsistence using RETs, was chosen. Indeed, these three main aspects of the topic (SSC, energy poverty, and rural development) deserve further research.

The implementation of development strategies, which apply to all aspects of rural development, would greatly benefit these villages. However, adaptation to local needs is required in all endeavors, thus the recommended development strategies presented at the end of this study have the potential of adaptation to other areas of rural development such as health, education, and the non-farm rural economy. Due to the time constraints and the inability to conduct field research, this study’s main focus is based on the application of development strategies within the framework of SSC. This research emphasized a qualitative analytical approach with the inclusion of some quantitative data analysis to support the information gathered with the qualitative methods. Analysis was completed based on qualitative data collection methods, which included desk research, interactive research, and case study analysis.

1.2.1 Desk Research and Literature Review

The first goal of this study was to attain an understanding of what SSC encompasses. The concept of energy poverty as an inherent weakness of rural development was also a key topic required for the completion of this study. Without this initial groundwork, development strategies could not be recommended that would apply to the rural South. With this in mind, internet and literature research was conducted with the following objectives:

- Establish a clear definition of SSC and the various policies enacted under the multilateral framework;

- Review the relevant international instruments applicable to SSC;

- Define energy poverty and determine its influence on rural development;

- Gain an understanding of current international best practices addressing energy poverty in rural areas;

- Review the importance of RETs for rural development; and

- Determine the SSC framework under which development strategies could be recommended that would benefit overall rural development and address energy poverty.

Literature on the concept of SSC development strategies for energy poverty was not readily available. However, extensive research, through studies conducted by UN agencies and other organizations in addition to a few published books, was found on the SSC movement history and its main programmes of action. A thorough review of different UN agencies’ resolutions was required to provide a context in which development strategies could be recommended. It also allowed for a greater understanding on how the various governments of the South view SSC and energy access in rural areas. The most current information, case studies, and recommendations were found online through the websites of these various organizations and their published case studies.

With its growing popularity and the emergence of the BRICS economies, SSC has moved to the forefront of many bilateral agreements, UN agencies and international organizations’ mandates, and multilateral cooperative initiatives. On the other hand, the concept of energy poverty exists in many completed UN case studies, especially under the auspices of the various regional and country offices of the UNDP. However, studies on specific regional and global SSC strategies addressing energy poverty as a means towards achieving sustainable rural development are not readily available.

Energy poverty, rural development, and SSC are very large topics individually. There is always more to read on them, especially once one branches out and treats each topic individually. For example, energy poverty has an opposite side of the coin: energy security, which deals with the supply and demand of energy on a national scale. It is about the securitization of energy on a national and international scale. The specific focus of this study allowed for a more narrow analysis of this desk research and permitted a more critical approach towards the available publications from the various organizations conducting field work, case studies, and policy reviews.

1.2.2 Case Study Analysis

Due to time limitations and the lack of funding resources to complete field research, a full comprehensive review of selected case studies was limited. Going forward, field research could be completed within each village and a more comprehensive analytical study concluded on the various energy-related projects in rural areas of the South. Many governments and NGOs address energy poverty through their rural electrification programs (such is the case with China, Nepal, and South Africa for example). Visiting rural areas would allow for a more comprehensive study on the positive and negative outcomes of the application of decentralized RETs in rural areas. In many cases, the work of rural cooperatives also goes mostly undocumented. Thus, further case studies could be analyzed based on local initiatives and field research.

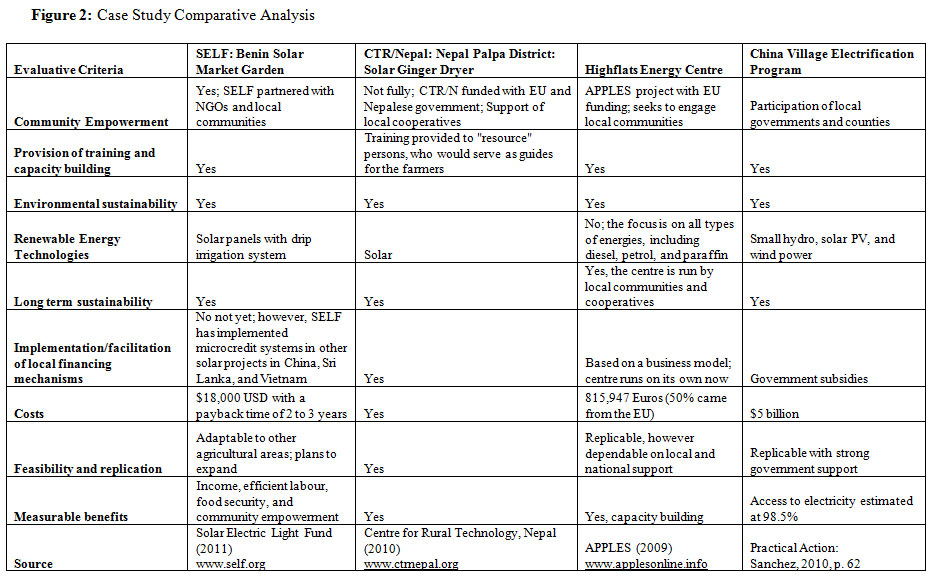

Notwithstanding these limitations, a review of available case study documentation was completed. The initial case studies selected for this research were based on the following evaluative criteria:

- Application of RETs;

- Community empowerment;

- Environmental sustainability;

- Feasibility of replication;

- Implementation of financing mechanisms that allow for local ownership;

- Long-tern developmental sustainability;

- Measurable benefits such as increased income; and

- The provision of training and capacity building.

The desk research allowed for the establishment of these preliminary criteria, which represent key elements required for the successful replication of these projects in other rural parts of the global South. With the correct development strategies in place, governments of the global South can set up the proper mechanisms to replicate these projects. The establishment of these evaluative criteria limited the choice of case studies for analysis as few projects were found that could truly serve as a basis by which comprehensive development strategies could be applied.

For this reason, a greater emphasis was placed on the analysis of SELF’s Solar Market Garden in the Northern District of Benin. Projects such as the solar ginger dryer in Nepal and the Highflats Energy Centre in South Africa address energy poverty in a limited manner. They do not necessarily represent easily replicable projects that could be implemented in other rural areas around the South as they lack a certain commonality with other rural areas. The Centre for Rural Technology, Nepal (CTR/N)’s Solar Ginger Drier focuses exclusively on dried goods, while the Highflats Energy Center does not provide for a suitable framework through which rural development can be addressed in an all encompassing manner such as SELF has achieved in Benin.

Notwithstanding, these projects and many others are important as their benefits in rural areas can be measured and experienced. An initial comparative case study analysis was completed for this research to ensure the feasibility of the Solar Market Garden’s replication potential. However, this comparative analysis does not serve as the main analytical framework for Chapter 3’s case study review[4]. Instead, the research focused on the measurable outcomes of the SELF project and its future replication potential throughout the global South.

1.2.3 Interactive Research

In addition to desk research and a case study analysis, interactive research was conducted to provide a context in which development strategies may be recommended based on the most current information from experts in the field. Interactive research was completed in two manners: through one-on-one interviews and through attendance at conferences in the Geneva area. The search for experts’ opinion allowed for further insight into the workings of various NGOs, international organizations, and governments. Without these, final recommendations on how to address energy poverty would not be as thorough. Personal communication interviews also allowed for a more analytical perspective to take place as the inclusion of expert opinions from those who work in the field helped fill the gap, which might have otherwise have been filled with fieldwork.

The goal behind interactive research was to avoid unnecessary repetition of recommended polices already made explicit through the various studies referenced in this research. Expert opinions allowed for recommendations to be based on current best practices and not just those which were referenced in publications. Moreover, this component of the research allowed for the final recommendations to be based on the present developmental context and the best way to move forward in addressing such an important problem as energy access in rural areas.

Finding the right experts to speak with was not an easy task in the fast paced environment of Geneva. Many practitioners are quite busy and had limited time available. Interviews were conducted in person where possible, however a certain level of flexibility was required and thus phone and email interviews were also completed. Many experts were also located outside of Geneva in locations such as Washington DC and Paris. A total of ten interviews were conducted with:

- Two UN Agencies

- Two NGOs working in rural areas

- Three NGOs based in Geneva

- One solar advocate; and

- One governmental Mission to the UN.

UN Agencies were chosen as entities which are truly international in scope; NGOs were selected due to their focus on specific issues and their ability to work closely with local populations; the interview with the solar advocate was conducted due to his experience in promoting solar energy with NGOs and social enterprises throughout the global South, while the opportunity to interview a governmental mission allowed for a greater understanding of the governmental barriers faced in the implementation of rural renewable energy policies.

Given more time, further interviews could be completed to deepen the research scope. Due to access constraints for these interviews, information gathered from conferences contributed towards the final research findings. The following conferences were attended:

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Conferences on South-South Cooperation held throughout Fall 2010 (the main focus was on the development of productive capacities);

- UNCTAD Short Course on South-South Cooperation held December 6, 2010;

- First International Gateway to Africa Conference titled “Africa’s Challenges Today and Tomorrow” held April 4-6, 2011; and

- UNCTAD Seminar on “Green Global Value Chains” held May 4, 2011.

These conferences provided a governmental perspective, which was missing from the interviews (as only one governmental interview was completed). In addition, these conferences permitted access to other experts in the field and increased an understanding of the research topic.

Data obtained from the interviews and the conferences was compared using a categorization system based on: Value of RETs, Dissemination Mechanisms, Value of SSC, Governmental Policies, and Financing Mechanisms. Once the data was separated into these various categories, a comparison was made between the interview and conference data obtained. In this manner, a final analysis was completed to determine best practices. Data collected from the interactive research was presented partially in Chapter 3, yet most of it can be found under Chapter 4. Overall, interviews and conferences provided the context in which development strategies could be recommended based on current policy space.

1.2.4 Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis

Case study data, interactive research, and quantitative data gathered from various sources lead to a thorough analysis of the many different aspects that affect energy poverty in rural areas. Data on these numerous factors was gathered from different sources with the goal of providing a comprehensive approach towards the establishment of SSC strategies. Without these different features, the final recommendations would be missing a key link. Thus, the following areas represented a key focus throughout this research:

- SSC policies;

- Financing mechanisms on a large scale (such as investments) and on a smaller scale (such as microfinancing);

- NGO and international organization projects and programmes;

- RETs policies, costs, and sustainability; and

- Rural development programmes.

Without a comprehensive review of these different areas, a complete analysis would not be possible.

To this end, interview responses, data obtained from conferences, and the literature review were categorized under the following headings:

- Financing Mechanisms;

- Government Policies;

- Programme Dissemination;

- Programme Replication;

- Value of RETs; and

- Value of SSC.

This initial categorization allowed for a more focused approach towards the literature review and the case study analysis. The goal was to combine expert opinions and experiences with the data obtained from the desk research.

Quantitative research was not based on the collection of new data, but on the analysis of existing data, which was obtained from many diverse sources to establish the necessary foundations required to recommend SSC development strategies, which seek to address the needs of the rural South. Quantitative data was collected to analyze the potential financing mechanisms required. Thus, FDI, Official Development Assistance (ODA), rural energy costs, and the Benin project costs were evaluated to obtain a true understanding of required costs.

Research on the costs of RETs was also completed to provide a context under which financing may occur. The results varied. The costs for each country, depending on infrastructure, transportation, and access to technology were mixed. Thus data on average costs was not easily found. Time constraints also prevented a calculation on these costs, as data collection of the national costs of each technology within the 130 or so countries of the South would not be feasible within the time frame provided for this study. As a result, average costs as calculated by Practical Action, an international development charity, and Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century (REN21), a network established by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), were used as a measurement. Both these organizations provided the most thorough data on the different types of RETs available to rural communities.

1.2.5 Final Analysis

Throughout this brief research period of three months, comparable projects to SELF’s were not found. Many projects did not meet more than 75% of the evaluative criteria mentioned above. Thus, this study focuses on SELF’s work in Benin and its potential for future replication in many others areas of the global South. In addition, the success of SELF in these two rural villages of Northern Benin is truly amazing. Its replication in other parts of the South would have positive long-term ramifications for many rural inhabitants. Thus, one of the main questions behind the case study analysis was: what made it so successful and how can it be replicated?

Final analyses of both quantitative and qualitative data lead to the creation of an Energy Access diagram, presented in Chapter 4. This diagram combines all the distinct elements involved in addressing energy poverty in rural areas. It is divided into three main elements: The Rural Cycle, based on access to RETs and knowledge awareness; Governments and SSC, based on Dissemination, Regulation, and Financing; and the Multiplier Effect, based on the long-term effects of the Rural Cycle’s positive outcomes.

Each of the main components could easily become a study of its own; however, due to the limitations of this research, focus was placed on the most salient features of each element with the goal of enhancing an understanding of each aspect and how it may affect rural renewable energy development. It is about scaling up small-scale projects into larger projects. The literature review provided the groundwork for the development of this diagram; however, it was the interactive research that allowed for the refining and adaptation of this concluding diagram to today’s current developmental context.

Consequently, Chapter 2 will present the literature review findings, whilst chapter 3 will introduce and analyze the selected case study and the possibility of its replication throughout the global South. In addition, this section seeks to demonstrate the long-term effects of addressing energy poverty in a sustainable manner in rural areas. Chapter 4 will recommend likely financing mechanisms and will also suggest SSC development strategies that could potentially serve as a future framework to address energy poverty in rural areas. Finally, Chapter 5 will present the conclusion of this study.

Chapter 2: Learning the Path

2.1 SOUTH-SOUTH COOPERATION’S CONTRIBUTION TO DEVELOPMENT

In its myriad forms, SSC has contributed to both urban and rural development since the mid-1950s at its inception. However, in many instances it has had limited success. To address energy poverty in rural areas, SSC will need to enhance its international instruments and strengthen South-South relationships. Due to the fact that most people living without electricity can be found in the South[5], it thus becomes imperative for SSC to seek mechanisms in which it can address this serious problem. It is not only a moral obligation, but also one related to economic factors. If rural development is not addressed, rural to urban migration will continue placing a further strain on the resources of urban areas and creating “brain drain” in rural areas.

Sound economic policy should include both urban and rural development. Notwithstanding these migratory patterns, this study will focus on the needs of rural areas, specifically related to access to sustainable energy, without which, rural development cannot move forward. SSC traces its history back for at least 60 years; in that time, it has established many mechanisms and international instruments that will pave the path for increased cooperation in rural development and in many other areas relevant to the global South.

2.1.1 History of SSC and its International Instruments

South-South Cooperation dates as far back as the mid-1950s and 1960s, when the Arab League was formed, the Latin America Free Trade Association was established, and the Cold War led to the creation of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM)[6]. However, it was not until 1964 when the Group of 77 (G-77) came to life under the auspices of UNCTAD that the idea of SSC established itself as its own entity.

Since then, SSC has taken on many different shapes and engendered alliances, partnerships, and agreements amongst the many developing nations of the South. However, the main goal of all these diverse organizations and initiatives has always been to promote economic and social development as declared within the Charter of Algiers (which established the G-77): “The representatives of developing countries, […] united by common aspirations and identity with their economic interests, and determined to pursue their joint efforts towards economic and social development, peace and prosperity” (Group of 77 [G-77], 1967, part 1). Under the context of the Cold War, the third world nations of the global South established a framework through which they could ensure the protection of their own interests and not have their interests subjected to the whims of the great powers of the time.

The idea of SSC originates in the NAM, the G-77, and most importantly in the enactment of the Buenos Aires Plan of Action.

On 12 September 1978 in Buenos Aires, capital of Argentina, delegations from 138 States adopted by consensus a Plan of Action for Promoting and Implementing Technical Cooperation among Developing Countries (TCDC). […] The consensus adoption of the Buenos Aires Plan of Action marked the full success of this Conference, tributes to which were still being paid in the United Nations General Assembly when, in December 1978, it resolved to endorse the Plan and urged all Governments and elements of the United Nations system to implement its recommendations. (UNDP, n.d.)

Based on this Plan of Action, UNDP established the “Special Unit for South-South Cooperation” in 1978 to help promote this cooperative initiative amongst these nations. This plan established the means through which SSC could become fully effective. It set out a list of recommendations for the national, subregional, regional, interregional, and global actors. It established an overall objective “for developing countries to foster national and collective self-reliance by promoting cooperation in all areas. The aim is to supplement, not supplant, cooperation with developed countries” (UN General Assembly, 2009, p. 3).

The framework under which SSC can succeed depends on the will to establish cooperation amongst all the different nations and to ensure that this will diffuses itself within the different communities and societies. Full sustainable and equitable development is not possible without the contribution of small stakeholders such as those present in rural areas. The Buenos Aires Plan of Action established clear objectives and recommendations for the global South to attain social and economic development.

Despite these vital goals, SSC as a movement relapsed throughout the 1970s and 1980s. It was not until the beginning of the current millennium that SSC regained its impetus. In the year 2000, the MDGs were implemented at the United Nations Summit in September of the same year. They called on all nations to commit to eight goals ranging from poverty eradication to environmental sustainability and the reduction of maternal and child mortality by 2015. The declaration itself states the following:

We believe that the central challenge we face today is to ensure that globalization becomes a positive force for all the world’s people. For while globalization offers great opportunities, at present its benefits are very unevenly shared, while its costs are unevenly distributed. We recognize that developing countries and countries with economies in transition face special difficulties in responding to this central challenge. Thus, only through broad and sustained efforts to create a shared future, based upon our common humanity in all its diversity, can globalization be made fully inclusive and equitable. These efforts must include policies and measures, at the global level, which correspond to the needs of developing countries and economies in transition and are formulated and implemented with their effective participation. (UN General Assembly, 2000, art. I.5)

For the developing South, these MDGs resonate clearly with the economic and social requirements needed to ensure true development. These goals are non-binding commitments to be fulfilled by both the global North and the global South. The responsibility lies with all nations. Following this declaration, SSC’s regained impetus led to many high-level conferences, declarations, agreements, and programmes of action that all call for the implementation of an effective SSC framework.

In the same year as the MDGs, the Havana Programme of Action reiterated the importance of SSC for the developing world. One of its main articles noted:

South-South cooperation is a crucially important tool for developing and strengthening the economic independence of developing countries and achieving development and as one of the means of ensuring the equitable and effective participation of developing countries in the emerging global economic order. (G-77, 2000, art. IV.1)

SSC permits the developing world to join forces and implement the necessary actions in order to achieve a similar development level as that of the global North. The main objectives for SSC under the Havana Programme of Action include the renewal of efforts “to stimulate the expansion of South-South trade and investment […] to strengthen cooperation in the monetary and financial field […], to strengthen cooperation in promoting social development [such as] the enhancing of capacity-building and human resources [and] to promote multilateral cooperation and arrangements towards the expansion of [SSC]” (G-77, 2000, art. IV). In conjunction with the Buenos Aires Plan of Action, SSC has a strong foothold on which to base its initiatives. Trade, multilateral cooperation, capacity building, technical cooperation, and many other important objectives have set the groundwork by which SSC may succeed.

Of particular note, the 2003 G-77 Marrakech Declaration on South-South Cooperation established a framework of implementation for SSC. Many of its provisions include the enhancement of coordination and joint efforts within multilateral settings such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), supporting existing platforms of regional cooperation, and promoting investment within developing nations (G-77, 2003). These latter objectives call for enhanced efforts towards the achievement of an equitable and sustainable developmental vision for the global South. The impetus exists in the South and the supporting legal instruments, both soft and hard, are also in place.

However, development within the South has not been equitable. Some nations have advanced further than others, while many have fallen even further behind. In this sense, SSC does not always represent a true exchange among equals. Common challenges continue to exist; yet the emergence of new global powers, especially those within the South, changes the rules of the game for both the North and the South.

2.1.2 The State of Development within the South

The rapid growth and emergence of the BRICS economies as new global players represents a clear advantage for the global South. “Malaysia, South Africa, India and Brazil have all been characterized by their extensive use of financial and political resources aimed at promoting developing-country perspectives in multilateral institutions and regional bodies” (Alden, 2010, p. 132). The promotion of the South’s interests by these emerging economies aids the promotion of their own interests. Their growing power permits them to exercise increasing influence within multilateral organizations. In fact, since the implementation of the Havana Programme of Action, “the G-77 noted that developing countries were committed to a global system based on the rule of international law, democracy in decision-making and the UN Charter. They drew attention to the importance of regional cooperation and integration as well as to the growing scientific and technological North-South gap” (Alden, 2010, p. 114).

The growing influence of the South, especially of the BRICS, displays a new shift in the natural order of North-South relations. In fact,

in 2009 China became the leading trade partner of Brazil, India and South Africa. The Indian multinational Tata is now the second most active investor in sub-Saharan Africa. Over 40% of the world’s researchers are now in Asia. As of 2008, developing countries were holding USD 4.2 trillion in foreign currency reserves, more than one and a half times the amount held by rich countries. (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], 2010, p. 15)

South-South trade is growing considerably in importance, as is its influence within the global market. The BRICS economies themselves have been paving this road through the expansion of FDI, research, trade, and investments.

The international arena reflects these emerging changes. However, a UNDP study noted that

the development context varies among the countries of the South. Some countries have taken a lead in South-South cooperation and do not require support from the United Nations system; others have requested UNDP support for their initiatives. Some countries have yet to fully recognize the potential of South-South cooperation and require encouragement to stimulate demand. (UNDP, 2007, p. X)

The various nations of the South are not developing under the same terms, conditions, and advantages. The agenda and subsequent initiatives for SSC must consider the various social and economic conditions, which these nations share, to help bridge the development gap. International organizations and UN agencies have played an important role in aiding these agendas and programmes of action, however the real impetus for true cooperation must stem from the will of the governments themselves. In this respect, the development achieved by Brazil, India, China, and South Africa has set them apart from other nations. If SSC does not remodel itself to address the needs of the other hundred or so nations, than a new developmental gap will emerge within the South itself.

Notwithstanding this necessary remodeling, SSC is “viewed by those participating in it from the perspective of political solidarity of the South, utilization of complementarities between developing countries and direct cooperation between larger developing countries and other countries in the South” (Yu, 2009). The growth of the BRICS creates leader nations within the South that will allow for international solidarity amongst all these developing nations. The assurance that the promotion of the South’s development interests will be considered within the multilateral forum thanks to these leading BRICS represents a powerful mechanism under which SSC can and will flourish.

In fact, SSC embodies a forum under which best practices can be discussed within the framework of international cooperation, one that goes beyond the usual custom of international cooperation and transcends into a forum by which common challenges may be addressed. A United Nations General Assembly Resolution noted

the significant increase and expanded use of South-South cooperation by developing countries as an important and effective instrument of international cooperation, and in this connection urges developing countries in a position to do so to intensify technical and economic cooperation initiatives at the regional and interregional levels in areas such as health, education, training, agriculture, science and new technologies, and in particular information and communication technologies. (2002, p. 2)

The underdevelopment of rural areas throughout the South is one such area in which SSC can play an important role in ensuring that rural areas are not left behind in development plans.

Within the global South, a high percentage of the population still lives in rural areas[7]. In fact, “at least 70 per cent of the world’s very poor people are rural, and a large proportion of the poor and hungry are children and young people. Neither of these facts is likely to change in the immediate future, despite widespread urbanization and demographic changes in all regions” (IFAD, 2010, p. 16). The high percentage of people living in rural areas, in conditions of poverty, gives rise to an obligation by the international community to ensure access to resources with the goal of eradicating poverty. In fact,

there is an ongoing debate on how best to manage aid flows; there is a growing recognition that the current mix of bilateral and multilateral arrangements causes aid to be too politicized, too unpredictable, too conditional and too diffused to act as a catalyst for growth and domestic resource mobilization. A stronger South–South and regional dimension in coordinating and channelling aid flows may be one way to improve the effectiveness of the aid system. (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development [UNCTAD] Trade and Development Board, 2010, p. 18, art. 69)

This obligation rests heavily upon the shoulders of national governments.

Since these governments can mostly be found in the global South, the opportunity exists to truly create development strategies which are applicable to local contexts and which are based on best practices in regions with similar overall development challenges. In this respect,

developing countries have accumulated abundant experience in rural poverty reduction through their long-term anti-poverty endeavors. It has been proven by practice that it is easier for countries with similar stages, levels and philosophies of development to share experiences among themselves. South-South cooperation is undoubtedly a key mechanism for partnerships among developing countries. (Omura, 2010)

Thus SSC serves as the framework under which rural development can be accomplished. Since the world’s poor live mostly in rural areas, elevating rural development to the forefront of SSC will be key towards ensuring an equitable and sustainable development for all. Addressing energy poverty represents one of the first steps towards achieving this goal.

2.2 THE PATH TOWARDS DEVELOPMENT

Energy poverty and rural underdevelopment go hand in hand. Access to electricity permits rural development, without which poverty may not be fully eradicated. Inadequate development in rural areas has lead to increased migration towards urban areas, further eroding the possibilities of development in rural areas as labour departs. This outward migration transforms into a detrimental migration of labour and innovation.

Unfortunately, circumstances in rural areas lead towards this increased migration. “1.6 billion people today do not have access to electricity, particularly in rural areas of developing countries” (Mueller, 2008, p. 166). A lack of access to electricity prevents innovation, education, and a well-balanced progress for all involved. Unfortunately, extending electricity services towards these areas has met with many challenges such as financing and proximity to urban centers and/or electric grids. Although,

Energy is a basic necessity for human activity and economic and social development […], global strategies for how to meet this basic need for the world’s rapidly growing population are sorely lacking. Lack of energy services is directly correlated with key elements of poverty, including low education levels, restriction of opportunity to subsistence activity, and conflict. (Baker Institute Energy Forum, n.d.)

Rural development transcends beyond a moral imperative to aid the world’s poor and meeting a key MDG goal. It has the potential to address economic development for the entire nation and ensure a balanced social development for the people of a nation. Unfortunately, rural development has not been prioritized in many key SSC instruments.

In many areas of the global rural South, agriculture represents a key component for survival; it also helps ensure food security within a nation. However, many small farmers are barely able to feed themselves, much less take their goods to the market. “Electricity allows tasks previously performed by hand or animal power to be done much more quickly with electric powered machines. Electric lighting allows individuals to extend the length of time spent on production and hence on income producing activities” (Baker Institute Energy Forum, n.d.). Energy leads to an overall improvement in the livelihoods of rural stakeholders. Without it, rural development cannot take place. Forthcoming agendas to address rural development under SSC will need to consider energy development as a key component of its programmes.

2.2.1 Energy and Rural Development

Energy poverty is closely linked with rural development, especially in the global South, where many of the world’s rural populations can be found living without access to electricity, a commodity which is taken for granted throughout the North and in many urban areas of the world. In addition,

the production of energy also affects agriculture at the global level. Energy consumption and income are linked. It is estimated that there are five billion low-income people in countries with rapid economic growth rate. These people are increasingly looking for additional energy suppliers. (Mueller, 2008, p. 166)

Demand for energy exists, yet the market does not seem to have effectively adjusted to supply this demand. In many rural areas, distance from urban zones inhibits access to electricity and impedes natural market mechanisms due to a lack of infrastructure. Under these circumstances, alternative solutions such as decentralized electricity generation through renewable energy sources represent the best solutions.

Notwithstanding, “grid electricity has been the most important means of increasing electricity access in the past, including in urban and peri-urban areas […]. However, for rural areas and especially for isolated areas this option becomes economically uncompetitive compared to standalone options” (Sanchez, 2010, p. 37). Energy poverty strategies must address these isolated areas, but they must go beyond the simple provision of energy services. Sustainable options will need to be provided if rural development is to truly succeed in the long-term. “When burned, traditional fuels often produce hazardous chemicals with negative health impacts, especially when used indoors” (UNCTAD, 2010, p. 2). In addition, “traditional fuels cannot produce a range of modern energy services such as mechanical power and electricity limits their ability to improve other aspects of life, including education and employment” (UNCTAD, 2010, p. 3). A reliance on traditional fuels to generate energy for daily usage is not sustainable in the long-term and affects the health of the household.

Renewable energy will be needed for rural areas to ensure energy sustainability and long-term viability. “RETs are energy-providing technologies that utilize energy sources in ways that do not deplete the Earth’s natural resources and are as environmentally benign as possible. […] By exploiting these energy sources, RETs have great potential to meet the energy needs of rural societies in a sustainable way” (UNCTAD, 2010, p. 5). Solar power, wind power, and hydropower are some examples of RETs, which can be used to address rural development. Their sustainable and generally environmentally friendly nature also implies long-term viability. Start-up costs are usually high, especially for solar power. However, in the medium and long-term, their benefits far outweigh their costs.

2.2.2 Energy Poverty and SSC

Renewable energy usually entails decentralized systems of power generation, which are off-grid and hence more easily accessible to rural populations located far from normal grid access. “One of the most important advantages of small decentralized systems is that they can be sized according to the specific needs of a community and they allow the involvement of the users at all stages of implementation, encouraging control and ownership by the users” (Sanchez, 2010, p. 39). Decentralized rural electrification not only ensures local participation, but also allows for the implementation of RETs, thus guaranteeing environmental sustainability.

In fact, these “renewable energy technologies are fertile ground for innovation; the possibilities for further developments and cost reductions are from being exhausted” (World Bank, 1996, p. 62). The advantages of these technologies are numerous; these sustainable technologies are environmentally friendly and cost effective in the long run. However,

new renewable energy technologies still account for less than 2 percent of the primary energy supplies of developing countries, but in light of their promise, with good economic and environmental policies and with the development of the necessary support systems for installation and maintenance, their market shares should expand. Investments will also be required to acquaint energy engineers and managers with the technologies and to educate and train engineers and skilled workers. (World Bank, 1996, p. 62)

The developing countries of the global South have a clear opportunity to implement policies that promote RETs, which will be beneficial for rural areas’ environments and allow for economic development.

Trade in energy technologies will be key to allow SSC in conjunction with the North to enable access to these technologies for rural villages. For the success of RETs, training, and capacity building epitomize mandatory components. A World Bank study in the Pacific islands concluded that

many PV [solar/photovoltaic] systems failed after installation, and it was only when supporting services were introduced that the programs began to succeed. These services included training technicians, ensuring timely maintenance, collecting fees on a regular basis, providing proper oversight to prevent the diversion of revenues to other projects, and obtaining prompt feedback on needs from local user communities and passing the information on to the supplying utility. (1996, p. 62)

The technology exists, however inherent weaknesses persist in its implementation. Without training and capacity building, the South will be unable to implement the necessary policies and programmes to address energy poverty as a part of rural development. “Successful programs require two main ingredients: (a) paying proper attention to program development, for example, initiating surveys of renewable energy resources, carrying out project identification and preparation, and investing in education and training; and (b) creating good enabling conditions through economically efficient pricing, credit, and tax policies” (World Bank, 1996, p. 64). NGOs and international organizations create the proper conditions for programme development, while pricing, credit, and tax policies are the responsibility of the local and national government.

However, the role of the smallest stakeholders must not be underestimated. “These [rural] households may rely to varying degrees on smallholder farming, agricultural wage labour, wage or self-employment in the rural non-farm economy and migration. While some households rely primarily on one type of livelihood, most share a tendency to diversify their livelihoods base, to the extent possible, as a way to reduce risk and to maximize income” (IFAD, 2010, p. 70). The rural populace’s income base is not very diverse, hence the need to address energy poverty as a means towards expanding this income base. Access to sustainable electricity improves efficiency of small-holder farming and agricultural wage labour; wage and self-employment in the rural non-farm economy benefit from electricity access through innovation and efficient production.

In addition, the value of remittances obtained through migrant family members transforms this income into further investments. “Mobility out of poverty is associated with personal initiative and empowerment, and is highly correlated with household characteristics such as education and ownership of physical assets” (IFAD, 2010, p. 70). All of these factors contribute to better livelihoods in rural areas.

With these characteristics in place, projects may succeed. However, a lack of access to electricity inhibits their true progress:

Without modern energy services, millions of women and children face debilitating illness or premature death; basic social goods like health care and education are more costly in both real and human terms, and economic development is harder to perpetuate. The services that energy enables, such as electricity, can create conditions for improved living standards, especially in areas of public health, education, and family life. (Baker Institute Energy Forum, n.d.)

The provision of energy services to rural areas cannot be successful without the participation of local communities. Thus, “facilitating the empowerment of poor people—by making state and social institutions more responsive to them—is also key to reducing poverty” (World Bank, 2000, p. 3). In this respect, the work of grassroots organizations and NGOs stand out in these societies.

Most projects and programmes implemented are established directly within rural areas and with the participation of the local population. “Actions will generally be necessary in all three clusters—opportunity, empowerment, and security—because of the complementarities among the three” (World Bank, 2000, p. 7). National policies and good governance on a local and national level thus play a key role in ensuring that these grassroots organizations and NGOs may expand their work and aid other local communities. In the global South, national governments should note that

in rapidly developing agricultural regions, the provision of electricity helps to raise the productivity of local agro-industrial and commercial activities by supplying motive power, refrigeration, lightning, and process heating. In turn, increased earnings from agriculture and local industry and commerce raises households’ demands for electricity. However, when development efforts fail because of, say, poor crop pricing and marketing policies, electricity supplies may be able to do little to remedy the situation, nor will electricity or other modern fuels be in great demand. If it is to serve a useful purpose, electricity needs a “market,” as do other energy forms such as LPG [liquefied petroleum gas] and renewables. (World Bank, 1996, p. 39)

Development policies must reflect the demand and supply needs of a market. On the other hand, the environment in which a market may succeed must be first created.

By enabling a market for energy services in rural areas, potential development policies may succeed, as opportunities, local empowerment, and economic security become a daily part of rural lives, allowing people to improve their living standards. One improved household multiplies into several and eventually raises the economic standards of a whole nation. Thus the diverse roles played by the various actors in rural areas overlap and must be coordinated to ensure maximum benefits are achieved. “Market reforms can be central in expanding opportunities for poor people, but reforms need to reflect local and institutional and structural conditions” (World Bank, 2000, p. 7). In addition, market reforms allow for energy services to expand in rural communities; however, the groundwork must first be set through rural community participation, NGOs’ assistance, and effective, fair, and honest governmental reforms to minimize bureaucratic impediments.

Since many of the rural villages, which represent the focus of this study, are unable to access an electric grid, decentralized energy systems become a more cost-effective option to ensure access to electricity. “Decentralization that fosters community-driven choices for resource use and project implementation” (World Bank, 2000, p. 9) ensures local participation and the most effective mechanisms through which energy poverty can be addressed for the “roughly 1.6 billion people, which is one quarter of the global population” (Baker Institute Energy Forum, n.d.) without access to electricity in the global South. SSC can take on many shapes. Thus, its benefits for the Southern nations are clear. Targeting SSC development strategies towards addressing energy poverty in rural areas is key to sustain and to promote development for the nation overall. This fits in clearly with the stated goals of SSC.

Electricity’s contribution to development in any shape or form cannot be underestimated. Thus, development and energy poverty go hand in hand; for the success of development, the necessary policies must be in place to allow for economic growth. However, economic growth will be stalled if access to electricity is inexistent or very small; hence, the existence of an energy-development nexus. The addition of renewable technologies to this equation leads this nexus to expand into a new one: an energy-development-sustainability nexus. Hence, SSC encompasses this nexus and must seek to promote the sharing of best practices as well as the implementation of development projects.

With the growing BRICS economies, the South now has the necessary resources to propel SSC development policies even further. To ensure that the remaining Southern nations achieve economic growth, the North has an important role to play in assisting the South through their knowledge, technologies, and additional financing. Yet for SSC to succeed, projects should be implemented from the South for the South. Thus the North may act under the triangular cooperation umbrella or through the independent actions of numerous NGOs. However, the main task of energy provision will lie in the hands of the South itself.

Chapter 3: Forging the Path

3.1 COMBATING ENERGY POVERTY IN RURAL AREAS

The value of RETs is widely accepted; however this has not lead to their widespread use. High costs have usually inhibited their usage:

In the past, renewable energy has generally been more expensive to produce and use than fossil fuels. Renewable resources are often located in remote areas, and it is expensive to build power lines to the cities where the electricity they produce is needed. The use of renewable sources is also limited by the fact that they are not always available — cloudy days reduce solar power; calm days reduce wind power; and droughts reduce the water available for hydropower. (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2010c)

Standard non-renewable energy sources such as coal and oil still play an important role, if not a predominant one, in the matter of energy consumption around the world.

According to a United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) report, modern energy contributes to poverty reduction and rural development by

reducing the share of household income spent on cooking, lighting, and space heating; Improving the ability to cook staple foods; reducing post-harvest losses through better preservation; enabling irrigation to increase food production and access to nutrition; enabling enterprise development, utilizing locally available resources, and creating jobs; generating light to permit income generation beyond daylight; and powering machinery to increase productivity. (2009, p. 24)

RETs have already been defined in the previous chapter. Their value lies in their long-term sustainability not just for the environment, but for the livelihoods of rural populations. “The UN Millennium Development Goal of eradicating extreme poverty and hunger by 2015 will not be achieved unless substantial progress is made on improving energy access” (OECD/IEA, 2010, p. 14). Unfortunately, renewable energy has been stigmatized: the high start-up costs usually associated with these technologies inhibit their promotion and implementation. Most stakeholders do not think of their long-term cost effectiveness and viability.

It is not just about the environment, but also about better business practices, ones in which health and daily living standards are clearly affected. “Given the high costs of grid extension into areas of relatively sparse population and low energy demands, the rural areas are currently the most promising markets for alternative or renewable forms of energy generation” (Wiens, n.d., p. 1). The dilemma arises when a lack of knowledge on a local, national, or regional basis prevents true rural initiatives from flourishing.

However, there have been successful cases of energy development in rural areas. For example, China’s Rural Electrification Program based on hydro, solar, and wind power has brought energy to 98.5% of the population (Sanchez, 2010, p. 62); in fact, by 2015 the China Village Electrification program is expected to implement full electrification (Sanchez, 2010, p. 62). On the other hand, in Kenya, Practical Action East Africa funded a micro-hydro project, which now “generates an estimated 18 kilowatts of electrical energy. This amount can light 90 homes and Practical Action estimates that the power the system generates will benefit about 200 households” (Practical Action East Africa, n.d.). Many other projects around the world have implemented governmental and/or non-governmental initiatives to address the pressing concern of energy poverty in rural areas.

For a truly successful energy development program, the case of SELF is of particular note as it meets the main evaluative criteria noted above that will permit its replication in other villages. Based on an analysis of various case studies and the work of NGOs, certain elements are necessary for the success of rural renewable energy projects. RETs represent a path through which rural villages may gain access to electricity. Their generally decentralized nature offsets the costs of extending the electric grid to these villages[8].