In this paper I will write using a feminist perspective, and investigate the overall concept of “intersectionality[1],” which can be found in two major events in the battle for gender equality in Switzerland. With regard to intersectionality, “Intersectionality does not produce a normative straightjacket for monitoring feminist inquiry in search of the ‘correct line’. Instead, it encourages each feminist scholar to engage critically with her own assumptions in the interests of reflexive, critical and accountable feminist inquiry” (Davis (2008) page 70). Thus, the goal of this paper is not to demonstrate that there is only one answer, but on the contrary, I attempt to give a discourse that aims to encourage involvedness, original opinions, and try to, throughout the whole, give ways to develop new questions for feminist scholars.

This paper focuses on women’s political emancipation in 1971 in Switzerland. This key date is when women finally got the right to vote on national issues. It may seem surprising for other democratic nations to learn that women, in one of the oldest modern democracies in Europe, lacked the right to express their voice on national matters well past the middle of the twentieth century. Nevertheless, women finally gained that right and as such, won another battle towards gender equality by crossing many social barriers.

Swiss women’s political emancipation took place not long after 1968, a key year in which the “Sexual Revolution” took place throughout the Western world. Through this revolution, the female role was redefined. Developments took place due to social, economic, technological, medical, and other advancements in our society. It was increasingly eminent that women would bring more to society, rather than staying in their traditional role, which was often defined by staying at home.

This paper investigates the relationship between the two key emancipation events that were major steps in the battle for gender-equality in Switzerland. I neglect any racial issues because it is a subject that, as far as my research goes, had very little influence on this matter, in Switzerland. As such, my thesis is that the “Sexual Revolution” influenced the success of emancipation in the political realm of Switzerland. Nevertheless, I shall demonstrate later in the paper that the previous event (the sexual revolution of women) was not essential in the establishment of new rights for women, but merely advanced the success of the political emancipation. Therefore, in order to be able to successfully investigate the relationship, my problem statement is: Did the Swiss “Sexual Revolution” of ‘68 influence the women’s political emancipation of ‘71 in Switzerland?

In order to effectively answer the problem statement mentioned above, there are three main parts to the paper, and it is essential to go through those three steps in order to understand their relationship with the political emancipation of women, and to find any link there may be between them. First, the “Sexual Revolution” of ’68 is investigated. In light of the event, I will try to explore how it may have emerged, and then, explore how ‘68 affected the roles of women. The goal throughout this section is to gain a better knowledge of what happened during that key event.

The second part of the paper focuses on the women’s political emancipation of 1971. More information shall follow in regard to what women’s political emancipation actually means. As was done in the previous chapter, I attempt to find the initiating social class. With anything that has to do with Swiss political decisions, a referendum was initiated over this matter, and it is interesting to investigate the pros and cons that existed during that period. The importance of this section is that it will help to find a clearer relationship between the ‘68 event and the ‘71 event.

The last section attempts to answer the problem statement; which is trying to figure out how the “Sexual Revolution” influenced women’s political emancipation three years later. As such, this section is composed of two sub-parts, with the first attempting to demonstrate the affiliation between the two happenings. The purpose is to reveal the correctness of the first part of the theory stated above, which affirms an actual link between them. The second sub-part is meant to exhibit the redundant importance of the link between them by demonstrating how much Switzerland actually changed after 1971.

Chapter 1: Sexual Revolution 1968

The Sexual Revolution is also known as the “sexual liberation.” I have taken the time to give a synonym to the ‘68 event because, even though the word sex is in it, its contextualization has no relevance to the true purpose of the event. On the contrary, it was just part of many other changes. Throughout the era, it is true that there was a differentiation between “erotic” and “pornography.” This enabled people, mainly females, to acquire new attire, such as clothes that would have been labeled as “trashy” in the previous generation. To keep this topic short, I plan to share the fundamental difference, which was noted in a documentary entitled Comprendre la liberation sexuelle qui est ineluctable from the “Television Suisse Romande” (TSR), which aired on 20/06/1968: Erotism is cold, since it is a matter of intellect and Pornography is warm because it is working around the lust of any human.

However, as mentioned above, the revolution was not solely about sexual content. On the contrary, its main focus was any social outlook which challenged the role of women in Western society. Throughout the whole period, intersectional roles of women emerged and gained space in mainstream Western society. People generally took new stances over contraception, the pill, public nudity, the normalization of other sexual orientations other than heterosexuality, and depending on whom you ask, the most important one was the legalization of abortion.[2]

I believe that we are able to possess a fundamental understanding in regard to what the Sexual Revolution was actually about. Nevertheless, it is questionable where this whole stream of changes began. Through my research, it was not clear exactly where it actually began. Nonetheless, it becomes clear that it emerged from the social class labeled as the “Elite Class.” This encompasses all upper class, business, successful, and influential circles, and is a highly educated community. The logic behind this reasoning is quite basic as far as it can be conveyed. In order for new thoughts to emerge, there needs to be a certain independence for it to happen. As such, it needed to emerge from a social background where higher education and a certain level of autonomy existed. Hence, the sexual revolution would never have happened if the elite class did not exist. After all, ‘68 enabled the transfer of this revolution to the rest of society, and as a result, it democratized the social movement.

So far, I have defined the sexual revolution and where it originated from. This revolution changed how women perceived themselves in Western society. It could be defined so far as a “new breed” of female emerging in the world. In order to convey this flow of thought, it is my belief that Kamen has showcased the best example in her book, Her way: young women remake the sexual revolution (2000). In it, she analyzes the Clinton-Lewinsky affair that took place in the USA in the 90s. In this passage, she clearly points out the difference between women who lived and were raised prior to, and after, 1968: “overall, Lewinsky, raised in the 1980s, acted entirely differently than the typical 21-year-old woman raised in the 1950s and 1960s would have done. Young women today feel entitled to conduct their sex lives on their own terms” (Kamen (2000) page 2). To rephrase this quote in a much larger sense, women started to act as men had before; they take control and are not afraid to have superior rule. It seems that beforehand, women were supposed to stay in the shadow of a man and be happy with such a role. Happily, now women are finally able to do a number of different things and are able to talk on equal terms with their colleagues.

The problem statement of this paper has been developed to study the relationships and importance that emerged from the sexual revolution, which occurred throughout the Western world in regard to women’s political emancipation. In accordance, I have noted the characterization, the origin, and the changes it shaped.

Chapter 2: Women’s Political Emancipation of 1971

In the previous chapter, the focus was on the sexual revolution, but this chapter will focus on women’s political emancipation. A fundamental knowledge of the two feminist movements is essential to have, in order to be able to analyze any relationship between them. In this chapter, I will define what exactly the 1971 emancipation was about. Additionally, I will also discuss the emergence which made it possible, and the arguments of both parties.

Emancipation, also known as ex manus capere (take out of the hand), is used to define the battle process from one era to another through extreme changes, and it usually refers to a specific community within our society. In this case, “emancipation” defines the battle in which women finally entered an era where they had the right to take part in the Swiss Confederation’s politics as Swiss citizens. After all, all national decisions in Switzerland are made through referendums because, unlike its peers, it uses a direct democracy system. This referendum took place in 1971. However, it was not the first attempt in the Confederation to give women the right to vote, in fact, initial voting took place in 1952. Conversely, whenever the constitution is susceptible to change through a referendum, a total of 2/3 of the voters must vote yes. However, in 1952, only half of the voters supported women’s political emancipation.

Nevertheless, dissimilar to the rest of the Western world, Switzerland was the last nation in Western Europe to offer equal citizenship at a political level between genders. This means that the Confederation went through the Sexual Revolution before it agreed to not differentiate between a man and a woman. Nonetheless, if there is any true link between the two events, then it will be discussed later on.

Women’s emancipation has now been sufficiently defined. To continue on, we will attempt to reflect on the emergence of the desire for equality, and this is no easy matter. The reason is that, in an era where women were often not taken seriously, it was difficult to keep track of the evolution of their thoughts. However, it is possible to date the start of the battle to the end of the 19th century. This assumption, of course, does not mean in any way the feminist movement did not exist before in the rest of Europe. The first recognized feminist association was established in 1868.[3] One of the members of this organization, Emilie Kempin-Spyri[4], the first female federal lawyer, claimed that all women should have the right to vote. Kempin-Spyri argued her position by referring to the Swiss Constitution: “All Swiss are equal before the law.” This means that despite gender, there should be no special treatment before the law. Their first win can be dated to a century later, to the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, when some cantons, especially in the French part of Switzerland, such as in Vaud, Geneva, and Neuchatel, offered a certain level of emancipation which enabled women to vote on all matters besides those pertaining to the Confederation. As such, it is evident that the whole process of gender-equality was by no means a new issue by the end of the 60’s. Additionally, some women (though very few) already had a position in the Swiss Parliament at the start of the 60’s.

Thus, it becomes clear that the ones who began the movement, which resulted in the granting of emancipation for all women, were from the elite sphere. What I mean by this is that the women who started fighting for gender-equality had many years of studies behind them from the start. Consequently, it becomes evident that such an event can clearly be linked to the elite social class.

In this chapter, thus far, I have detailed both what women’s emancipation was about, and its origin. However, I have not yet discussed the debates that were exchanged between the supporters of, and the opposition to, the referendum. I will describe both camps’ arguments because it will provide a better understanding of how people thought in a time when it was not generally accepted that women were equal vis-à-vis to men. Also, it came to my attention that the composition of one side or another was not based on the gender of the people, as can be seen in many documentaries. Moreover, on September 17th, 1967, a journalist went to the streets to ask the opinion of simple street walkers in the Swiss city of Sion (Canton Valais) about extending the right to vote to women.[5] It is clear that this matter divided the nation, even despite an individual’s gender, social status, or any other background.

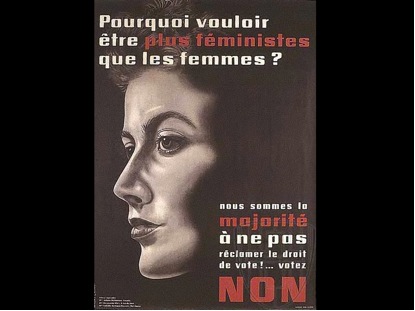

The arguments that were raised, to a certain extent, lacked any originality. For instance, the side that was against noted that the majority of women actually did not want such a right (See Appendix 1). Through the mentioned poster, it becomes evident that a wish to give women the right to vote was nothing more than fiction and that it should not be something to be granted for their own good.

The first reasoning is based on biological arguments. It was claimed that since women’s brains were smaller, they would lack the intelligence of men when it came to voting on the correct issue. Additionally, it was feared that they would start new habits where they would abandon their position at home and start campaigns. Second, their modest nature would prone them to natural inequality. It was believed that since a woman was naturally kind, then she would not go vote. Even more, since there was a larger birth rate in the countryside, it was feared that an unfair advantage over city populations would arise. Lastly, it was also a question of male pride. If a woman was actually elected, this would be the high point of humiliation for any man. He would end up doing a woman’s chores in his own home. Naturally, with time, each of those ideas was proven wrong. Nevertheless, such views lasted until 1993 when it was stated in the Swiss constitution that all genders are expected to receive equal treatment.[6]

All of the reasons for letting a woman vote are so evident that it seems almost futile to state them. Nevertheless, for the purpose of this paper, I still intend to pinpoint three that are, in my opinion, the most important, and are also why people eventually decided to support the cause.

The primary reason was provided in the previous century. In the Swiss constitution, it is written that all are equal, despite being a woman or a man, in front of the law (article 8).[7] Thus, fundamentally, women should be enabled to vote. The second reason regards the fact that there is no difference of intellectual capability between a man and a woman. This means that despite gender, a person would still make the same kind of decision.

The third point is in regard to the percentage of the population. Entering the 20th century, the population of women was superior to the male population.[8] Also, 51.1% of the population in 1970 was composed of women and consequently only 48.8% was of male gender.[9] Therefore, letting a minority of the population decide how the country should be run lasted for far too long.

As was mentioned, the purpose of this paper is to examine if there are any apparent influences between the Social Revolution and women’s political emancipation. The first chapter focused on the subject of the Sexual Revolution, which took place throughout the Western world in 1968. Thus, I have defined the event, discussed the emergence of its origin, and discussed how it has influenced the world afterwards. This chapter focused on the entire process in order to extend the realm of the right to vote to also include women. I have defined the event of ‘71, its emergence, and the subjects of debate which made extending voting rights to women such an important issue.

Having discussed the two main events, the next chapter will focus on any links that can be drawn between them. Moreover, I will show to what extent Switzerland actually changed once women’s voting rights were adopted.

Chapter 3: Discussion of the Relationship of the Events

In order for this paper to be logical, I have discussed the base of what constituted the sexual revolution, also known as the social revolution in 1968, and women’s political emancipation in 1971. Now, I can start to link them in an attempt to finish this chapter with a clear answer to the problem statement. After all, the purpose of this paper is to investigate if there is a relationship between the one that took place in 1968 and the one that took place in 1971, and if there is, how deep is the relationship. To do so, I plan to showcase any relationship that they have. In addition, in order to grasp the importance of the relationship between the two events, I shall illustrate how much Switzerland changed after 1971.

It is my opinion that there are three apparent links that can be drawn. The main links regard women’s role in our society, equal treatment between genders, and proving myths are nothing more than myths. In order to gain a better understanding of those topics, more details will be provided.

The first point is in regard to the role that a woman has in a society. It was largely perceived that a woman had her place at home. She was expected to clean the house, prepare meals, and take care of the children. Meanwhile, the man would have to acquire a job and insure financial stability. Though, this way of thinking strongly changed. The vision of ‘68 and ’71 has shown that women can bring much more to society. In ‘68, it meant that they could influence the economic aspect, meaning, that it was not only the man that would have to work. In ‘71, it implied that a woman should have the same respect when it came to politics.

The second point is in regard to the equality of gender. This means that the feminist movement had the chance to successfully prove that despite their sex, the quality of the workload would not differ. “We would produce new terms to delineate what they cannot. In the meantime, gender variance, cannot be relied on to produce a radical and oppositional politics simply by virtue of representing difference” (Cohen & Kennedy (2000) p. 560). Such a statement gives a clear reasoning as to why it was no longer possible to differentiate the ends by the means.

The third point is about fictional myths, which discredited the female gender. It was believed that women lacked intelligence due to their brains being smaller. Furthermore, since they give birth, they tended to be more modest and less objective, in order to make the right decisions when it mattered most. It is quite evident by looking at their treatment and input in modern society that such myths have been disproven.

Even though I have shown links, in no way can I prove that those links were intertwined just between the two events. The reason is that, even before the social revolution took place, there had already been a couple of attempts to extend the right to vote to women in Switzerland. Accordingly, it seems that even though both of the events had a major influence on the evolution of gender equality, they each happened for reasons which are different, and affected separate areas. To summarize, the sexual revolution affected the social role in Western women’s emancipation and changed their political participation. Eventually, this would have a big influence in how Switzerland would be shaped.

In order to prove the above statement, I shall demonstrate what actually changed after 1971. Poll attendance rose slightly but not significantly. Also, there have been studies, such as the one from Burton and Russell, which affirm that the outcome of voting is influenced by the income of the individual and not by gender: “evidence I beginning to build that suffrage extensions that lower the income if the decisive voter leads to an expansion of the public sector redistribution in particular.”[10]

The intersectionality aspect of this paper demonstrates that two different waves of feminism have taken place. I have demonstrated that different aspects have been found in both events. Nonetheless, the links between them are phony. What is meant is that even though one can find issues and solutions that may occur in both areas, their impact leaves them autonomous from each other. Hence, the sexual revolution of ’68 was purely a social wave and consequently, the women’s emancipation of ’71, a political wave.

Conclusion

To conclude, I can now answer the initial problem statement, which discusses if there was any influence originating from the Sexual Revolution of 1968 on the women’s political emancipation of 1971. My first theory, as written in the introduction, is that women’s political emancipation was greatly influenced by the movement of ‘68. As it was shown in the previous chapter, it is irrelevant and therefore, erroneous. Nevertheless my second theory is that the emancipation would still have taken place even if the movement was inexistent. Since both events were not linked directly to each other, my second thesis is, at a certain level, accurate.

The reason is that even though both events left a significant mark in feminist history, none of them was related to the other. Indeed, the fight for women’s suffrage in Switzerland can be dated back to the 19th century. Additionally, many cantons had already given the opportunity of equality between genders, a decade before the social revolution occurred. The sexual revolution may have made its mark in Switzerland, however, it did not focus itself on that country. On the contrary, it occurred throughout the Western world, and thus, had a more general meaning which ended up only changing the social aspects.

Thus, it was not the social revolution that influenced the emancipation in 1971. Nevertheless, it can be questioned if it was not the battle for women’s suffrage that influenced the impact of the Sexual Revolution when it occurred in Switzerland in 1968. Further investigation is needed in order to file a response to this new theory that seems to have emerged from this paper.

Appendix

Closset, A. (1952) Pourquoi vouloir etre plus feminists que les femmes? Votez Non. Retrieved December 16, 2010 from http://ccsa.admin.ch/cgi-bin/hi-res/get_thumb.cgi?image=GEVBGE_Da1567.jpg

Bibliography

Ackermann, G. (Journalist), Dalain, Y. (Director) (1962, February 1) Le Vote Des Femmes, Actualites. Television Suisse Romande Archives from http://archives.tsr.ch/player/integrale-votefemme

Ackermann, G. (Journalist), Dalain, Y. (Director) (1962, February 1) Eve A L’Urne. Television Suisse Romande Archives from http://archives.tsr.ch/player/suffrage-eve

Bardet, F. (Director) (1968, June 20). La Liberation Sexuelle. Continent Sans Visa. Television Suisse Romande Archives from http://archives.tsr.ch/player/integrale-liberationsexe

Banaszak, L. (1996). Why movements succeed or fail: Opportunity, Culture, and the Struggle for Woman Suffrage. Publisher Princeton University, New Jersey USA

Banaszak, L. (1996). When Waves Collide: Cycles of Protest and the Swiss and American Women’s Movements (pp. 837-860) in Political Research Quarterly. Publisher Pennsylvania State University, USA

Bezaguet, L. (2010, March 5). A Geneve, le droit de vote des femmes a 50 ans. Tribunes de Genève. Geneva, Switzerland

Burton, A. Abrams; Russell, F. Settle (1999). Women’s suffrage and growth of the welfare state (pp. 289-300) in Public Choice, Publisher Springer

Cohen, R.; Kennedy, P. (2000). Race and Ethnicity (pp. 106-111). In Global Sociology. Publisher New York University Press. New York, USA

Daniels, R. (1989). Year of the Heroic Guerrilla: World Revolution and Counterrevolution in 1968. Publisher Besic Books, Inc. Ed First Harvard University Press Paperback, USA

Edge, S. (1995). ‘Women are trouble, did you know that Fergus’Neil Jordan’s The Crying Game (pp. 173-186). In Feminist Review.

Häusermann, S.; Mach A.; Papadopoulos, Y. (2004). Corporation to Political Science Review (pp. 33-59) in Swiss Political Science Review. Publisher Swiss Political Science Association

Kamen, P. (2000). Her Way: Young Women remake the Sexual Revolution. Publisher New York University Press, New York and London

Keller M. (2007, September28) Beaucoup de femmes votes toujours comme il y a 87 ans, soit pas du tout. Tribunes de Genève. Geneva, Switzerland

Nicod J-F (Journalist), Pichard, F. (Director) (1968, March 16). Femmes et Politique. Madame TV. Television Suisse Romande Archives from http://archives.tsr.ch/player/politique-femme

Nicod J-F (Journalist), Pichard, F. (Director) (1968, March 16). Et les Femmes. Madame TV. Television Suisse Romande Archives from http://archives.tsr.ch/player/politique-femme2

Nussle, A. (Journalist), Pellaud J-C (Director) (1970, September 19) La femme du Gardiem. Madame TV. Television Suisse Romande Archives from http://archives.tsr.ch/player/suffrage-evolene

Pasteur, C; Genoud, A; Breithaupt, F. (2008, March 8) Trois femmes, trios generations. Tribunes de Genève. Geneva, Switzerland

Swiss Confederation (1999, April 18). Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation of 18 April 199. Retrieved December 19, 2010 from http://www.admin.ch/ch/e/rs/c101.html

Swiss Federal Statistics Office (2009). Homme et Femmes: Population residante selon le sexe. Etat et Structure de la population – Indicateurs. Retrieved December 16, 2010 from http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/fr/index/themen/01/02/blank/key/frauen_und_maenner.html

Swissworld.org (n.d.) Women. Retrieved December 4, 2010 from http://www.swissworld.org/en/history/the_20th_century/women/

Swissworld.org (n.d.) The Right to Vote. Retrieved December 15, 2010 from http://www.swissworld.org/en/people/women/the_right_to_vote/

Webster’s Online Dictionary (n.d.) Definition of intersectionality. Retrieved December 18, 2010 from http://www.websters-online-dictionary.org/definitions/intersectionality?cx=partner-pub-0939450753529744%3Av0qd01-tdlq&cof=FORID%3A9&ie=UTF-8&q=intersectionality&sa=Search#922

Women’s Suffrage (n.d.) Women in Politics. Retrieved December 4, 2010 from http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/suffrage.htm

Zoller, P-H. (Journalist), Caviezel, A. (Director) (1969, June 1). Question de Mentalite. Horizons. Television Suisse Romande Archives from http://archives.tsr.ch/player/suffrage-paysans

Zuercher, C. (2008, December 10). Le vote des femmes, un droit acquis tardivement en Suisse. Tribune de Genève. Geneva, Switzerland

(2010) Women, Business and the Law: Measuring Legal Gender Parity for Entrepreneurs and Workers in 128 Economies. Publisher The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, Washington D.C. USA

(1967, September 19) Carrefour 19.09.67. Carrefour. Television Suisse Romande Archives from http://archives.tsr.ch/player/integrale-mcar670919

(1967, September 19) Le Vote aux Femmes. Carrefour. Television Suisse Romande Archives from http://archives.tsr.ch/player/inconnu-votefemme

[1] Intersectionality is a theory which seeks to examine the ways in which various socially and culturally constructed categories interact on multiple levels to manifest themselves as inequality in society (Source: Webster-Online.com).

[2] Kamen, P. (2000)

[3] Swissworld.org (n.d.) The Right to Vote

[4] Swissworld.org (n.d.) The Right to Vote

[5] (1967, September 19) Carrefour 19.09.67. Carrefour

[6] (2010) Women, Business and the Law: Measuring Legal Gender Parity for Entrepreneurs and Workers in 128 Economies

[7] Swiss Confederation (1999, April 18)

[8] Swiss Federal Statistics Office (2009)

[9] Swiss Federal Statistics Office (2009)

[10] Burton, A. Abrams; Russell, F. Settle (1999) p. 298

—

Written by: Pierce N. S. Lohman

Written at: Maastricht University

Written for: Anna Martens

Date written: December 2010

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- “The Women in White” – Protesting for a Peaceful Political Emancipation in Belarus

- Silent Birangonas: Sexual Violence, Women’s Voices and Male Conflict Narratives

- How Does Hegemonic Masculinity Influence Wartime Sexual Violence?

- Emancipation and Epistemological Hierarchy: Why Research Methods Are Always Political

- How the Securitisation of Sexual Violence in Conflict Fails Us

- ISIS’ Use of Sexual Violence as a Strategy of Terrorism in Iraq