As the scale of the horrors of the Holocaust was unveiled, presidents, diplomats, military leaders, and journalists were galvanised in their commitment that never again would such atrocities be allowed to go unchallenged. And yet, on several occasions over the following 60 years, that is precisely what happened: on the killing fields of Cambodia; during the slaughter of the Kurds in Iraq; as Bosnian Serbs murdered thousands of Muslims; and while Hutus in Rwanda tried to eliminate the Tutsi people.

As the scale of the horrors of the Holocaust was unveiled, presidents, diplomats, military leaders, and journalists were galvanised in their commitment that never again would such atrocities be allowed to go unchallenged. And yet, on several occasions over the following 60 years, that is precisely what happened: on the killing fields of Cambodia; during the slaughter of the Kurds in Iraq; as Bosnian Serbs murdered thousands of Muslims; and while Hutus in Rwanda tried to eliminate the Tutsi people.

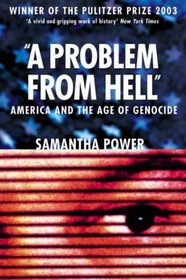

In her Pulitzer Prize winning “A Problem from Hell”: America and the Age of Genocide, journalist, academic, and currently Special Assistant to President Obama, Samantha Power explores America’s shamefully ineffective response to genocide in the Twentieth Century. As the sole power with the military, financial, and diplomatic arsenal to pursue meaningful intervention, America’s inaction emboldened mass murderers and genocidal tyrants. Why, asks Power, did America stand so idly by?

Worse than America’s “toleration of unspeakable atrocities,”[1] argues Power, was that on occasion the United States directly or indirectly aided those committing genocide. It orchestrated the vote in the UN Credentials Committee to favour the Khmer Rouge; it supplied agricultural and manufacturing credits to Iraq while Saddam Hussein was trying to wipe out the country’s Kurds; it maintained an arms embargo against the Bosnian Muslims preventing them from defending themselves; and it pressed the UN Security Council to withdraw UN peacekeepers from Rwanda.

Using a chronological framework Power explores America’s response, or lack thereof, to the genocides in Cambodia, Iraq, Bosnia [including a separate chapter on the Srebrenica massacre], Rwanda and Kosovo. She also looks back pre-Holocaust, to the Turkish genocide of Armenians, before providing an instructive chapter on the origins of the term itself[2] and its unanimous passage into international law at the United Nations General Assembly in 1948; the product of a remarkable 15-year battle by Raphael Lemkin, a Polish linguist and lawyer of Jewish descent who lost 49 relatives in the Holocaust and emigrated to the United States in 1941. But as Power concludes the chapter she notes despairingly that it would be nearly four decades before the United States would ratify the treaty and fifty years before anyone would be convicted for genocide.

In answering her own question, why America did so little, Power challenges the two most common responses given by presidents, state officials, military leaders and journalists through the decades. First, that government simply didn’t know. This wasn’t true, counters Power. The information was imperfect and officials did not know all there was to know about the nature and scale of the violence but “they knew a remarkable amount.”[3]

Second, that the United States could have done little to stop the horrors. Although impossible to prove the outcome of actions never tried, Power cites America’s successes in creating a safe haven for Kurds in Northern Iraq; in bringing the Bosnian War to an end after three and a half years; in pressuring Hutu militias not to attack the Tutsi inhabitants of a hotel after a phone call from a US diplomat. Even these small belated steps, posits Power, saved hundreds of thousands of lives: “If the United States had made genocide prevention a priority, it could have saved countless more.”[4]

The real reason the United States did not do what it could and should have done to stop genocide – out of both moral necessity and self-interest – was not a lack of knowledge or influence, concludes Power, but a lack of will. American leaders believed genocide was wrong, but were not prepared to invest the military, financial, diplomatic or domestic capital needed to stop it. With war fatigue from two costly missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, and a troubled economy, it’s unlikely that modus operandi is set to change in the near future.

Chris McCarthy is a member of the e-IR editorial team. He is currently at KCL’s War Studies Department, holds an MSc in International Public Policy from UCL and a BA in History from Durham University.

[1] Power, Samantha, “A Problem from Hell”: America and the Age of Genocide, (London; Harper Perennial, 2007), p503

[2] The word genocide is a hybrid that combined the Greek derivative geno, meaning “race” or “tribe”, with the Latin derivative cide from caedere, meaning “killing.”

[3] Power, “A Problem from Hell”, p505

[4] Power, “A Problem from Hell”, p507