A moral, political & operational defense for the coalition’s military intervention in the 2011 Libyan uprising

On October 30th of 2011—shortly after the death of Muammar al-Qaddafi on August 23rd—NATO’s operations in Libya officially ended. With the final arrests of the Qaddafi circle, the people of Libya liberated themselves from a dictatorship that spanned over four decades. As Libyans now begin a new chapter in building a legitimate government of their own, some are still debating whether intervention in Libya was ever justified. Although Libyans took ownership of their revolution from the beginning, these efforts would have been fruitless were it not for the internationally backed coalition intervention. Indeed, the use of military force to protect civilians is an extremely delicate process with a highly contentious history. While most would agree that the relatively recent international recognition of humanitarian norms has positively contributed to the reduction of mass atrocities, military force justly remains a last resort option in the scope of foreign policy tools. When used, these emergency responses necessitate essential preconditions before becoming a viable foreign policy strategy. The following is an attempt to provide a case for military force applied to humanitarian intervention by observing the unique case of the Libyan Revolution of 2011.

I. MORAL OBLIGATION: THE COSTS OF INACTION

“Worse than war is the systematic killing of civilians as the world turns a blind eye.”

-Nicholas D. Kristof, New York Times, 3.3.2011

Substantive ethical arguments for the use of military force in order to protect civilians must prove that the costs of inaction would have been greater than were the costs of action. Because of Libya’s extreme repression and lock-down of communication that only intensified after the February 17th movement kicked off, our knowledge of the crimes committed against the Libyan people is limited to the independent reporting of civilians, journalists, and international human rights groups. While evidence of mass atrocities continued to transpire after the coalition involvement (i.e. the discovery of ‘13 more mass graves’[i]), this report will limit itself to evidence that was public before intervention because it aims to explain the international impetus for military interference. A cross examination of these reports reveals very significant reasons to believe hundreds of thousands of lives were at risk. Even if one were to ignore the historical and economic factors that imply Qaddafi’s potential for brutality, the moral case for intervention can confidently be made by exploring the conduct of the Libyan government forces in the context of Qaddafi’s threats. By following his rhetoric and actions, this section intends to emphasize the costs of inaction consisting of: 1) Libyans dying on a massive scale; 2) Qaddafi possibly remaining in power for years; and 3) a message being sent out to all dictators that ruthlessness and brutality works.

Qaddafi’s Actions & Rhetoric

“We are coming tonight. We will find you in your closets. We will have no mercy and no pity.”

-Muammar al-Qaddafi in a speech directed at Benghazi residents, 3.17.2011

As early as February 22nd the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navi Pillay, declared that the attacks against the Libyan people were both “widespread and systematic”—potentially amounting to crimes against humanity[ii]. Three days later and less than a week into the civilian protests, Ms. Pillay confirmed independent reports from human rights organizations that: “thousands may have been killed or injured”[iii]. By February 26th the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) had referred the case to the International Criminal Court (ICC) for crimes against humanity, all the while drawing on Libya’s responsibility to protect its citizens[iv]. In early March, the bombing by Libyan Air force of civilian populated towns in the east finally prompted the rebels to reluctantly call-in a formal request for foreign intervention[v].

For two weeks these requests for military assistance by Libya’s National Transitional Council (NTC) went completely unanswered as the world watched Qaddafi’s forces use planes, tanks, and gunboats on non-combatants in rebel-held territory[vi]. By March 12th, the then-president of the NTC, Mustafa Abdel Jalil, warned that if Qaddafi’s forces were to successfully bomb-and-advance into the rebel stronghold of Benghazi—as defected-Libyan pilots made clear Qaddafi’s intentions were[vii]—the onslaught would result in “the death of a half a million” people[viii]. On March 16th, the day before UNSCR 1973 was passed, Qaddafi’s son and military commander, Saif al-Islam declared: “The military operations are finished. In 48 hours everything will be over. Our forces are close to Benghazi.” Concerning the UNSC vote for intervention, he said: “Whatever decision is taken, it will be too late.”[ix]

The words “too late” galvanized the world’s political leaders at the emergency session of the UN Security Council. The rhetoric the Qaddafis had used up to this point was unequivocally clear. On February 20th, Saif al-Islam described the intended breadth and scope of the brutal government response. Saif warned the protesters that “thousands” would die, “rivers of blood would flow”, and that authorities would “fight [down] to the last man, woman, and bullet”[x]. Two days later, Qaddafi called on his supporters in a state television speech: “Come out of your homes and attack [the opposition] in their dens”. Muammar al-Qaddafi called the protesters “greasy rats” and “cockroaches”[xi]. His threats to “cleanse Libya house by house” harked back chilling memories of Rwanda, when in 1994 Radio Mille Collines’ broadcasts served to catalyze genocide[xii]. The speech praised the Chinese authorities’ crackdown of the famous protests in Tiananmen Square as an example of national unity being “worth more than a small number of protesters”. Surprisingly, Qaddafi’s rhetoric turned even more explicit when he dryly stated that: “anyone who plays games with the country’s unity will be executed”[xiii].

If the rhetoric could be dismissed as a maniacal scare tactic, the civilian body count certainly could not. Between February 15th & March 5th, two weeks before the NATO bombing campaign took place, 6,000 civilian casualties had been killed[xiv]. Only one week into the protests, Human Rights Watch submitted a report stating:

Colonel Gaddafi has admitted the systematic intent behind the violence unleashed on the Libyan population and has given cause for substantial concern that further violence will occur. [HRW 2.24.2011]

When it became evident that many within the Libyan military units were not going to fire on demonstrators, Qaddafi’s intentions were only made clearer by his conscription of thousands of African mercenaries that fall outside the normal line of command and control[xv]. Their march towards the rebel capital of Benghazi—a town with a population of 700,000—meant either the bloody end to a popular rebellion or a desperate last minute save by an international coalition.

Although it is impossible to determine how many lives were saved in averting Qaddafi’s takeover of the large eastern cities, his behavior in cities like Zawiya, Ras Lanuf, and Misrata showed an exemplary lack of concern for civilian life[xvi]. In Zawiya, Qaddafi’s forces bombed a mosque full of civilians[xvii], while at least 50 tanks opened fire on the city—by one protester’s account tearing it “down to the ashes”. In Ras Lanuf, Qaddafi’s warplanes fired missiles into residential areas[xviii]. Moreover, the indiscriminate rocket and mortar fire, as well as the landmines planted in and around Misrata resulted in up to 2,000 killed by the month of April[xix]. Furthermore, the International Criminal Court (ICC) later revealed in war crimes investigations that Qaddafi personally ordered the bombardment and starvation of the civilian population in Misrata[xx].

Qaddafi’s knowledge of the strategic significance in the NTC’s capital of Benghazi was clearly illustrated by the disposition of his military might towards the city[xxi]. His commitment to capturing the city at all costs was divulged when the International Federation for Human Rights revealed that on February 23rd: “130 [of Qaddafi’s] soldiers were executed by their [own] officers in Benghazi for refusing to fire on crowds of protesters”[xxii]. Just before the coalition forces produced air strikes that forced the retreat of Qaddafi’s troops, the fall of Benghazi seemed inevitable[xxiii]. Even if we assume the head of the NTC was exaggerating when he said 500,000 lives would be lost if Qaddafi’s forces were allowed to fully advance, there is no question that countless lives were saved[xxiv] by preventing an abrupt and violent end to the popular rebellion. Manal Omar, Director of the North Africa Programs at the United States Institute of Peace noted at a Brookings lecture[xxv]:

There’s a very strong acknowledgment consistently that the reason why Benghazi has the opposition and is able to operate, is due to the fact that the NATO intervened, and also an acknowledgment that they could have been Zawiya. [BI, Libya and the Responsibility to Protect 6.16.2011]

From the very beginning Qaddafi vowed to fight until “the last man standing, [and] even the last woman standing”[xxvi]. Not only did he declare that he would “die [in Libya] as a martyr”[xxvii], but a New York Times report revealed that Qaddafi had “tens of billions” of cash reserves (separate from the frozen international funds) to help finance a prolonged war against the rebels[xxviii]—forces which he already enjoyed tremendous military superiority over.

There is little doubt that Qaddafi would have continued to carry out his 42-year policy of eliminating opposition voices had he been given the chance[xxix]. Imagine a situation where Qaddafi was to stay in power and the intervention would have never taken place. Libya would enter into an era of isolation, sanction, and deprivation. Like North Korea, the international community would essentially be condemning the Libyan people to continuous poverty and degradation. The international implications for mass atrocity prevention would be crippling. The normative international principle of the Responsibility to Protect would be dealt a coup de grâce. Allowing the Qaddafis to stay in power rather than face the charges of both war crimes and crimes against humanity would have only empowered the tyrannical rulers of the world to use unrestrained violence in the future.

II. POLITICAL LEGITIMACY & LEGAL AUTHORITY

“I was the one who created Libya and I will be the one to destroy it.”

-Muammar al-Qaddafi directing pilots (who later defected) to bomb protesters, 2.20.2011[xxx]

Almost immediately after Qaddafi’s first violent reaction to the popular protests, an exodus of defectors began to emerge[xxxi]. By the time the emergency UN Security Council meeting took place in March, Qaddafi had very few people left to defend him. Calls from the Libyan people begged the international community to assist in every way short of direct military invasion. Upon hearing these desperate calls for help, diplomatic and popular support for stepping-in only increased. Qaddafi had effectively lost all domestic and international legitimacy. Regional support allowed for the most important political step needed to provide coalition assistance to the opposition.

What made the Libyan case so remarkable was not just the credible threat to a large civilian population, but the extent to which political and legal legitimacy for the operation was sought before launch. The Iraq invasion of 2003 provided an antithetical reference from which a legitimate mandate for Libyan intervention would be derived. Lessons from Iraq prompted both the NATO chief and the Obama Administration to set basic preconditions for deployment. NATO articulated their preconditions to be a: 1) demonstrable need; 2) clear legal basis; and 3) firm regional support. Similarly, the Obama Administration required: 1) local requests for intervention; 2) regional legitimacy; 3) legal legitimacy; and 4) a truly multilateral coalition that shared the burden of costs. The U.S. and NATO have both publically stated that these preconditions were all met[xxxii] [xxxiii]. By delineating how the coalition’s military actions were fulfilled, this section seeks to demonstrate its political legitimacy and legal authority.

Local Requests for Intervention

Mr. Jalil, the former-president of the NTC, gave his illustration of Libyan popular opinion when he quipped: “There is a feeling on the street that if Qaddafi can employ foreigners to fight for him then why cannot we?”[xxxiv] In order to provide basic political legitimacy, intervention would ideally have been requested from the Libyan population as a whole. Let us examine the credibility of the popular representation embodied in the NTC by looking at both data and on the ground, as well as coverage of public opinion.

While the NTC was not a representative body chosen through democratic elections, it is the de-facto interim-government of Libya and currently enjoys international recognition as their sole legitimate representative. However, at the time of intervention, the only country that had officially recognized the NTC was France, and the UN’s recognition of the NTC did not come until September 16th,2011[xxxv]. Nevertheless, the NTC defended its selection process by asserting that members were chosen in close collaboration with local tribes and revolutionary councils inside liberated zones[xxxvi]. Although its 45 members were chosen through a fairly narrow consultation process, the administrative body appears to boast extensive popular support[xxxvii].

Support for the NTC begins with the uniting of the populace against Muammar al-Qaddafi. Let us consider the percentage of the population represented in cities that are reported to have fallen out of Qaddafi’s control, even before tanks had been ordered to fire into crowds of peaceful protesters. As University of Michigan professor Juan Cole has pointed out, when one takes into account the populations of cities like Tobruk, Derna, Bayda, Benghazi, Zawiya, Zuara, and districts of Tripoli (Suq al-Juma & Tajourna), anywhere from 80-90% of the Libyan population is represented as anti-Qaddafi[xxxviii]. Clearly not all of the cities’ residents were participating in the February 17th movement, but it was from these cities that the vast majority of Libyans demanded a No-Fly Zone[xxxix]. Arezki Daoud, editor of the North Africa Journal, explained how already in the first week of the protests, Qaddafi had “few followers,” but that they were “very dangerous and very powerful. They’re essentially a trained security elite” Mr. Daoud went on to say on February 22nd: “Essentially all of the tribes are siding against [Qaddafi]. It’s unclear whether his own tribe is revolting. [But] the fact that Tripoli is revolting, which is the base of his tribe, says that even his tribe is against him.”[xl]

In what is arguably the first free Libyan public opinion poll, the Research and Consultation Center of the University of Benghazi (formerly Garyounis University) surveyed six liberated eastern cities and found that 92% of 2,500 respondents agreed with” the NTC “expresses the views and wishes of Libyans for change”. The same survey, conducted between March and April, found that 95% believe that it would be impossible to implement political reform if the Qaddafi family were to stay in power. Even more promising was that 96% of those polled shared the belief that Libya can pragmatically direct its revolutionary unity, specifically to build a democratic model based on a constitution that respects human rights[xli]. Although the survey cannot be seen as representing Libya as a whole (since it only covered eastern cities), it helps legitimize the NTC as a representative voice of the people.

On-the-ground reports of Libyan popular opinion before NATO took action overwhelmingly revealed intense frustration with the international community. The Guardian newspaper interviewed a chemical engineer in Libya just before the NATO campaign began. The incredulous resident cried: “Where are the air strikes? Why is the west waiting until it is too late? Sarkozy said it. Obama said it. Gaddafi must stop. So why do they do nothing? Is it just talk while we die?”[xlii] Another Libyan interviewed by the New York Times denounced the West as having “lost all credibility.” Harking back memories of Iraq in 1991, she went on to say: “I am not crying out of weakness […] but we will never forget the people who stood with us and the people who betrayed us.”[xliii] Many were beginning to wonder if it was too late to engage in a military intervention[xliv]. Perhaps that is why when NATO finally decided to intervene; the rebel capital of Benghazi resonated with relief in the form of “shouts of thanks to America and the West”[xlv].

Clear Legal Basis

“The biggest question people would ask me is how are we wiling to go with right to protect, and for [the opposition], it was hard for them to draw that line between regime change and protection of civilians. For them, it’s one. You can’t keep Qaddafi and expect people will remain safe. The moment that the international community starts to shift vision away from Libya, then Gaddafi will come in and Benghazi might then suffer the atrocities that it avoided.” -Manal Omar, Brookings Institute, 6.16.2011

Although the Responsibility to Protect is a useful principle for guiding international conventions, we must remember that it is simply a norm and not a law. In the Libyan case, there are two main issues to assess regarding the legality of the coalition intervention. The first legal question is whether the coalition had the legal right to intervene in Libya to begin with. The second is concerned with whether coalition forces were legally permitted to target loyalist forces—including Qaddafi himself.

Chapter 7 of the UN Charter provides a framework within which the Security Council may take enforcement action. The Security Council can “determine the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression” and take military and nonmilitary action to “restore international peace and security”. It was under this UN statute that France, the United Kingdom, and Lebanon proposed the adoption of the United Nations Security Council 1973. The vote on UNSCR 1973 provided the legal basis for military intervention in the Libyan Revolution by first demanding an immediate ceasefire, and then authorizing the international community to enforce a No-Fly Zone—approving “all necessary measures to protect civilians and civilian populated areas”[xlvi]. On March 17th the measure was unanimously adopted with ten Security Council member countries voting in the affirmative, five abstaining, and none opposing[xlvii]. UNSCR 1973 thus specifically authorized all coalition intervention—“excluding a foreign occupation force of any form on any part of Libyan territory”—aimed at the protection of civilians[xlviii].

As mandated by the resolution, over the course of three months legitimate attempts at “immediate ceasefire” repeatedly took place to no avail. All other viable political alternatives were completely exhausted leading up to the commitment of regime change. Negotiations proved to be near impossible when Qaddafi reaffirmed that his word could not be trusted. On March 18th Qaddafi formally accepted a ceasefire but failed to uphold it. His forces never stopped advancing-into and firing-on the southern outskirts of Benghazi as well as on the rebel city of Ajdabiyah[xlix]. It was only after it became blatantly obvious that Qaddafi showed no intention of suspending his military, that coalition leaders announced the start of military intervention[l]. At the beginning of April, the rebels offered a ceasefire agreement that included the withdrawal of loyalist forces from in and around opposition cities so that Libyans could safely protest—Qaddafi once again refused[li]. After such striking insincerity, the opposition could no longer afford to take chances and accept another disingenuous and piecemeal offer of a ceasefire. In mid-April, the Libyan leader met with delegates of the African Union and appeared to have accepted a “roadmap to peace”[lii]. However, the opposition rejected the deal, arguing that it was non-binding and did not address the issue of Qaddafi’s ouster[liii]. The NTC then toughened their conditions, clearly stating that there would be no ceasefire negotiation without the incorporation of a political process leading up to Qaddafi’s departure[liv]. Not surprisingly, when Qaddafi once again proposed a truce, he refused to accept the condition of ceding power[lv], effectively proposing a partition of the country. Since such an outcome would cripple the economy and completely contradicted one of the major goals of the revolution—to keep Libya unified—the opposition refused to consider it[lvi]. Last-ditch ceasefire negotiations through South African president Jacob Zuma suffered the same fate, as Qaddafi refused to accept a Libya without his supremacy and loyalist forces continued indiscriminate attacks[lvii]. With no reliable partner in political negotiation, military force was the only option that remained for the ousting of the Qaddafi regime.

The broad language of the resolution, not only licenses air support for the Libyan people, but also legally warrants the targeting of Libyan government forces. Targeted attacks on government forces are legally warranted because their engagement in the state’s crackdown have proved to pose an inherent existential threat to the civilian population. This threat has been covered in previous sections (see Moral Obligation: The Costs of Inaction), as well as heavily documented in the UN Human Rights Council’s International Commission of Inquiry for Libya. The report found that the threat to civilians included but was not limited to: 1) the use of indiscriminate and prohibited weapons in civilian populated areas (expanding bullets, cluster munitions, mines, white phosphorous, mortars, etc.); 2) the use of mercenaries; 3) arbitrary detention and torture; 4) denial of access to medical care; 5) sexual violence; and 6) the use of children in armed conflict[lviii]. Because these threats are posed by the Libyan government forces on the civilian population, UNSCR 1973 authorizes the elimination of these forces in order to protect “civilians and civilian populated areas”. It does not exclude the targeting of top officials—especially Qaddafi—as long as loyalist forces were to continue to carry out the systematic killing of civilians. Furthermore, some have falsely assumed that arming the opposition violates the UNSCR 1970 arms embargo imposed on Libya on February 26th 2011. In fact, UNSCR 1973 explicitly addresses this possible overlap by authorizing: “all necessary measures, notwithstanding paragraph 9 of resolution 1970”. Therefore, as Hillary Clinton has been keen to point out[lix], the resolution’s language specifically references the arms embargo in order to make a temporary exception[lx].

Firm Regional Support

While there were certainly Arab voices warning of imperialism and oil seizures and Israeli conspiracies, the overwhelming majority actively demanded Western intervention to protect the Libyan people and their revolution. The urgency of preventing the coming massacre mattered more to them, and despite all the legacies of Iraq they determined that the United States and the international community take on that responsibility. -Marc Lynch, Foreign Policy, 8.22.2011

Most analysts would agree that the biggest political obstacle for action rested in the consent of the Arab world. Without the Arab world’s explicit request for coalition intervention, the West risked being accused of neocolonial imperialist exercise. Thanks to Qaddafi’s unambiguous brutality—as well as his belligerence towards Arab neighbors over 42 years—those that favored supporting the Libyan opposition quickly emerged. Remarkably, a regional consensus transpired within mere weeks. Our survey of Arab solidarity in backing the Libyan opposition examines the reaction of influential regional IGOs and NGOs, as well as Arab popular sentiment. We then conclude the section by briefly evaluating the significance of responses from African countries in the region.

By February 25th, before even the formation of the NTC, 200 Arab NGOs coordinated their efforts by calling for the protection of civilians in Libya through a UN-sponsored and Arab League-led No-Fly Zone (NFZ)[lxi]. The diverse groups spanned 18 countries and included a public statement signed by 35 prominent Arab intellectuals:

The Libyan people are living through a defining moment in their history. Their demands for basic human rights and an end to 42 years of cruel oppression are legitimate. We shall not stand silent and watch them pay the price of this demand with their blood. Without urgent action from the UN Security Council supported by the EU, African Union and Arab League, the window of opportunity to protect civilians from the threat of further atrocities will close. We believe it is the personal and moral responsibility of each and every one of you to ensure immediate action is taken to stop the bloodshed in line with Chapter 7 of the UN Charter. [CONDEMNATION IS NOT ENOUGH! 2.25.2011]

Among the punitive measures they petitioned were sanctions, asset freezes, and an arms embargo. The UN implemented all of them only two days later[lxii]. Although the Security Council did not approve enforcement of a NFZ until nearly a month later, there is no question the agency of NGOs and prominent figures in the Arab world served to increase pressure on regional IGOs and raise awareness in the international community.

On March 11th, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) denounced Qaddafi’s regime as illegitimate and called on the Arab League to take action so as to stop the bloodshed[lxiii]. After establishing contact with the NTC, the GCC stated its support for a NFZ, in turn urging the UN Security Council to shoulder the responsibility of protecting Libyan civilians[lxiv]. Citing Qaddafi’s use of “heavy weapons against civilians”, the employment of foreign mercenaries against his own people, and the rejection of humanitarian aid packages, the GCC went so far as to call for an end to Qaddafi’s rule[lxv]. The following day the Arab League voted unanimously to establish a NFZ over Libya. The secretary general of the Arab League, Amr Moussa, declared that the limited military engagement was a matter of “humanitarian action,” and was the only way of “supporting the Libyan people in their fight for freedom against a regime that is more and more disdainful” [lxvi]. Even the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC)—a 57-member state group not least famous for their democratic accomplishments—supported a NFZ intended to protect civilians from air raids[lxvii].

Perhaps even more important is the popular support for the Libyan opposition. As the Arab Spring creates a new global cultural paradigm, human dignity, democracy, and more participatory involvement in the political process are becoming unifying ideals amongst the youthful Middle Eastern and North African population. Many young Arabs have called for intervention in Libya in part to renew hopes in the wilting Arab Spring. Shadi Hamid, Director of Research at the Brookings Doha Center, points out that Arab popular support for the Libyan intervention far exceeds that of the Iraq war in 2003[lxviii]. In an April poll of 1,000 people across 16 Arab states, only 10% of respondents still thought that Qaddafi’s regime was legitimate—compare that to 41% backing the NTC. The same poll found that 75% supported the forcible removal of Qaddafi from power, although most would have liked to see Arab governments take the lead in mounting the operation. The poll also revealed that the majority of Arabs showed greater support than opposition for NATO’s NFZ over Libya—many stating that: “Arab states can’t react in a timely and effective manner; and Arab states are unable to play any role due to the wave of revolutions.”[lxix]

Finally, although some have argued that the international community has ignored the African Union’s opposition to the NFZ, we point out that three African countries (Nigeria, Gabon, & South Africa) voted in favor of UNSCR 1973[lxx]. In fact, China’s statement explained its decision to abstain (as opposed to ‘veto’) the resolution by directly citing their “consideration of the wishes of the Arab League and the African Union”[lxxi]. Yet, the African Union has never been a very effective regional group. To their credit, the Peace and Security Council of the African Union, “strongly [condemned] the indiscriminate and excessive use of force and lethal weapons against peaceful protesters, in violation of human rights.”[lxxii] But with a big membership, a huge diversity of situations, and conflicts of interest by way of boundless favors from the Qaddafi regime, it does not have a very robust platform in international affairs. Many forget to mention that it was only ten years ago that the African Union was establishment thanks to the leadership of Qaddafi himself[lxxiii]. The Financial Times referred to Qaddafi’s relationship with the continent as a “complex web of allegiances he has cultivated both among governments and paramilitary and insurgent groups”[lxxiv]. The same article goes on to describe the extent of his influence across Africa:

Col Gaddafi has commercial, military and political footprints across much of the continent, where he has concentrated efforts at extending Libyan influence since giving up on promoting Arab unity in the 1990s. He has channeled billions of dollars of investment into as many as 31 African states and provided backing to numerous African politicians and leaders. [Gaddafi calls in favours from Africa, Financial Times, 3.27.2011]

To be fair many African countries distanced themselves from Qaddafi early on in the military campaign[lxxv]. However, in the previously mentioned poll, a staggering 97% of Libyans did not see the African Union as a neutral mediator to resolve the Libyan crisis[lxxvi]. Their suspicion comes with good reason. In February of 2009 he was appointed chairman, even though his election “caused some unease among some of the group’s member nations”[lxxvii]. Qaddafi worked hard to create strong bonds with the leaders of the 54 member countries in hopes that he would someday realize his long-standing dream of a unified pan-African state rivaling the EU and US[lxxviii]. In light of the African Union’s political history, it’s clear that the regional group could not be separated from its close ties to the Qaddafi regime.

Multilateral Coalition

Figure 1: Breakdown of the UNSCR 1973 vote

Pledging political support and promising military participation are often mistakenly conflated in the realm of coalition building. Due to great American unease over another US intervention[lxxix], the Obama Administration focused their sights on the former, thereby building a coalition based on formal multilateralism. Learning from the mistakes of Iraq in 2003, Obama sought broad political endorsements for the intervention, signaling to the international community that the Libyan campaign was not going to be another Western unilateral inquisition. Although Resolution 1973 had five abstentions, the Security Council passed it without opposition. For the first time in the UN’s history, the body had passed a “blanket resolution”—limited by neither scope nor time—authorizing the use of force in order to protect civilians[lxxx]. However, because UNSCR 1973 explicitly ruled out the possibility of “a foreign occupation force of any form on any part of Libyan territory”[lxxxi], individual pledges for military contributions were limited to those countries that were both willing and possessed the capabilities of advanced aircraft and naval vessels. Therefore, the operational multilateralism—that which concerns actual military inputs—was largely made up of NATO’s more militarily robust member states, along with a few Arab partners providing airpower. Since we’ve covered the formal multilateralism demonstrated by broad Arab state support, the subsequent tables provide the empirical evidence of operational multilateralism in terms of the shared military and humanitarian contributions.

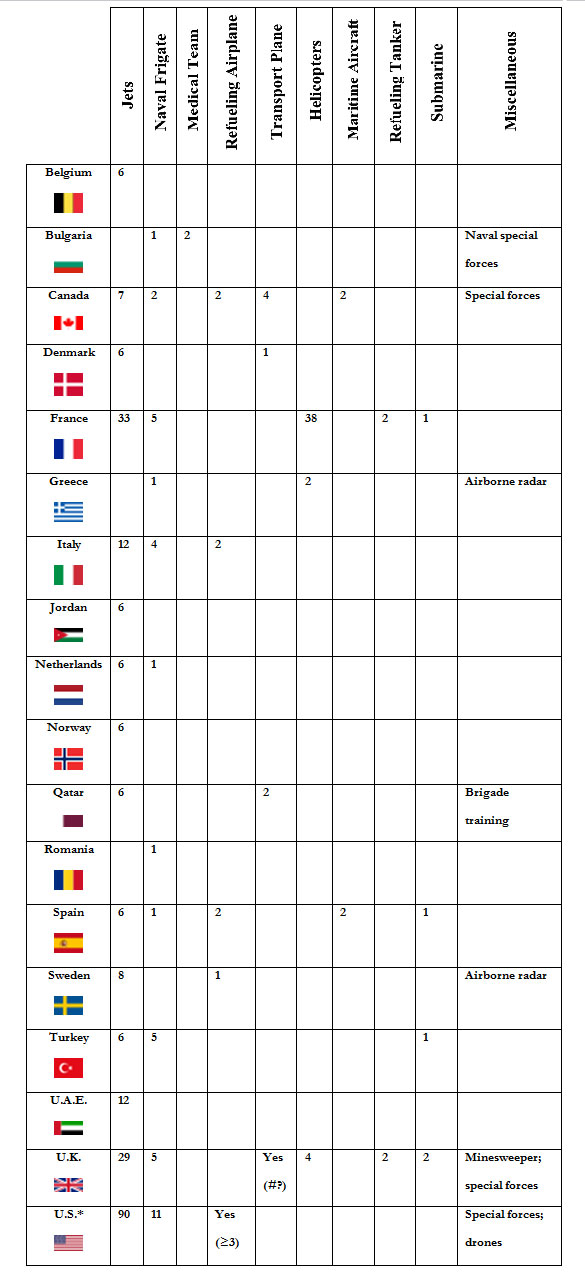

TABLE 1: ROUGH ASSESSMENT OF MILITARY CONTRIBUTION BY COUNTRY[lxxxii]

Note: In a little more than two weeks, the US officially relinquished operational control and withdrew its strike aircraft, transitioning into providing a supporting role.

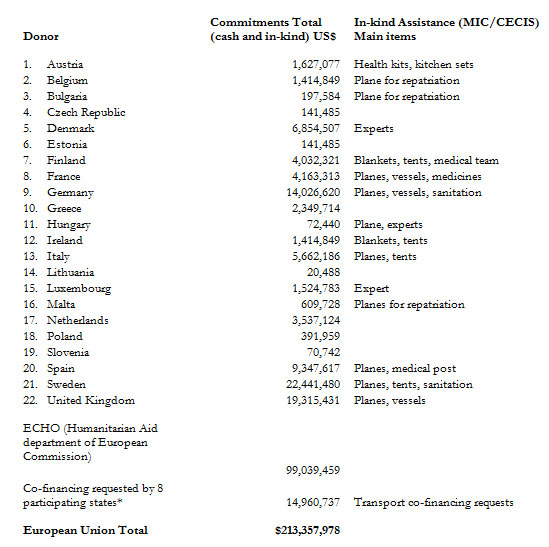

TABLE 2: SURVEY OF THE HUMANITARIAN AID BY COUNTRY[lxxxiii]

Note: *8 participating states are Belgium, Bulgaria, France, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Spain and Sweden

III. NATIONAL & REGIONAL INTERESTS

“Inaction is a decision, a policy with consequences. The wish to keep out of it all is entirely understandable; but it is every bit as much of a decision as acting.” -Tony Blair on Libya, Wall Street Journal, 3.19.2011

While the United States did not have “vital interests” in Libya, there were indirect political interests at stake. Beyond accomplishing a humanitarian goal, the political effect of supporting (rather than imposing) democratic change in Libya helps shift negative Arab perceptions of American foreign policy—especially with the youth-bulge, or so-called “Twitter and Facebook generation”. In aiding a popular struggle that is supported by Arab popular opinion, the U.S. signaled that its foreign policy narrative is willing to break with the American tradition of supporting repressive regimes. This stability paradigm that American foreign policy has stuck to over the last five decades has in many ways proved to be foolhardy in the realm of national security. There is a lot of evidence to show that the realist approach of backing regional “stability” through autocrats has itself contributed to the rise of Islamic extremism and militant radicalization[lxxxiv]. This section of the paper seeks to show how intervening in Libya served U.S. and regional interests by: 1) helping shift strategic perceptions of U.S. foreign policy; and 2) supporting our strategic allies in the European and Arab world.

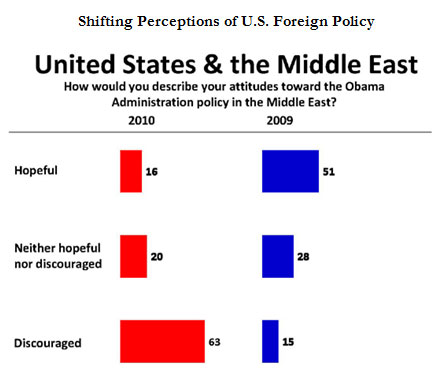

Figure 2: Brookings Institute Annual Arab Public Opinion Poll (2010)

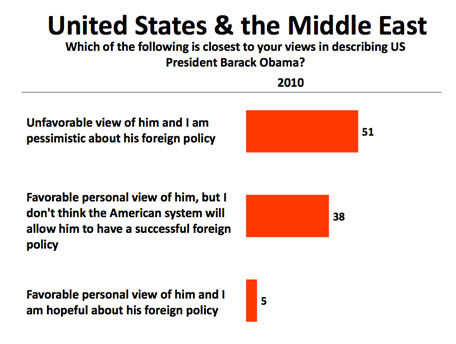

Like most Western powers, the United States has been caught on the wrong side of history on more than one occasion. The history of U.S. foreign policy in the Arab world has been plagued with ulterior motives and diplomatic hypocrisy[lxxxv]. American foreign policy has always publically championed democratic values, only to privately support regimes that rule through tyranny and show no concern for human rights. But diplomacy is always a complex balance of domestic and international concerns. Security interests like counterterrorism have made for strange diplomatic bedfellows. For instance, despite their incredibly repressive nature, the U.S. continues to support the corrupt regimes of Yemen[lxxxvi], Oman[lxxxvii], and Bahrain[lxxxviii]. Moreover, it was not until recently that the U.S. withdrew its support for the Mubarak regime in Egypt[lxxxix]. U.S. foreign policy cannot afford to continue to ignore Arab popular opinion. In an August 2010 survey conducted throughout the Arab world, 63% of those polled said they were “discouraged” towards the Obama Administration’s policy in the Middle East[xc] (see Figure 2). Yet the same poll shows that 38% have a “favorable personal view” of Obama (see Figure 3), implying that a revision of American foreign policy in light of the Arab Spring can significantly improve its image. For once, taking sides with the beleaguered people of Libya has aligned U.S. foreign policy actions with Arab popular sentiment. As Shadi Hamid from the Brookings Institute pointed out, “hatred of Qaddafi [trumped] anger towards the West”[xci].

Figure 3: Brookings Institute Annual Arab Public Opinion Poll (2010)

Regardless of Libya’s fate, the U.S. has improved its international standing by aligning itself with Arab support and working with the broad international community to prevent a grave humanitarian crisis. Former assistant defense secretary for the Reagan Administration, Lawrence Korb, has done a good job illustrating how in Libya “stopping the killing has gained us points in the Arab World and with our European allies”[xcii]. Alternatively, had the U.S. chosen to do nothing in the face of growing international consensus[xciii] against Qaddafi, it would have signaled to dictators that violence and brutality is an effective tool for staying in power. Libya’s certain isolation would have only increased Qaddafi’s will to interfere—as he had eagerly done in the past[xciv]—in the Arab uprisings of neighboring countries such as Tunisia and Egypt.

The troubled histories of Syria[xcv] and Algeria[xcvi] demonstrate how democratic movements can have a very difficult reemergence after facing systematic brutality and state crackdown. Libya sets a dramatic precedent for action on the part of the international community. A new ceiling, or international threshold, for state ruthlessness sends a message to would-be Qaddafis around the world. Long-run support for the universal democratic aspirations of Arabs will only continue to help reaffirm American political and moral leadership on the world stage. Just as the failure of these popular uprisings can lead to further militancy, their success can prove to be the antidote to Islamic extremism in the region. Since militant jihadists only represent marginal special interest groups in the Muslim world, supporting democratic movements will over the long-term naturally improve our national security condition. Perhaps American action in Libya can serve as the catalyst for a revised U.S. foreign policy that is more consistent with democratic values while remaining an effective counter-terrorism force.

Supporting Our Allies

With two wars and a budget crisis, from the outset the Obama Administration was more than reluctant to commit American resources in Libya[xcvii]. It was not until pressure from the European Union and the Arab League reached critical mass that the U.S. agreed to engage in a “limited capacity”. As we’ve shown in our analysis of coalition resources committed (see Table 1), U.S. military capacity was indispensable, even though its offensive leadership only lasted from March 19th to the 31st. One consequence of the “European demilitarization” trend that U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates has pointed out in the past[xcviii], is Europe’s reliance on unique American military capabilities. For better or for worse, European political aversion towards military investment means the U.S. will undoubtedly have to take a supporting role in securing future regional stability for its allies. If we evaluate the Libyan intervention on purely mercantilist terms, the U.S. is deeply indebted to its allies for their support in the wars of Iraq and Afghanistan. Had Qaddafi been permitted to continue killing his people, the long-term security of our Arab, African, and European allies would be at risk. Security experts have cautioned that al-Qaeda has in the past exploited the vast Saharan territory to serve as a safe-haven for planning attacks[xcix]. Investing in a democratic and unified Libya therefore works to stabilize regional security by preventing the proliferation of lawlessness, while looking out for the long-term energy security of our European allies.

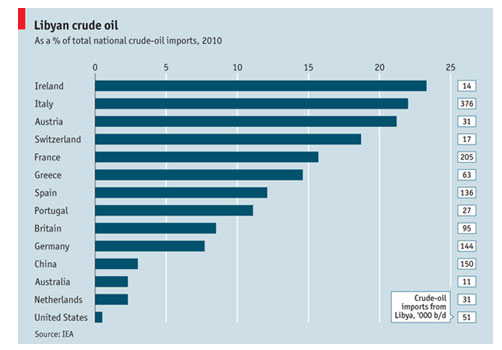

Some have simplistically argued that the only reason Western powers intervened in Libya was to secure oil interests. While future oil contracts certainly influenced the West’s engagement in Libya, it is highly unlikely that this prospect was enough to persuade it into endangering its existing contracts and the stability of world oil markets. Although Libya’s “sweet light crude oil” is highly valued due to its premium quality (low-sulfur content), it only accounts for 2% of the world’s oil supply[c]. Nevertheless, One might argue that with rising oil prices being considered a major threat to economic recovery[ci], it would be shortsighted to discount the extent to which the Libyan hydrocarbon industry fuels the economies of our allies. Indeed, Libya is the sixth largest energy supplier to the European Union and provides for 17% percent of all European energy needs[cii]. Below is a diagram of the countries that rely most on Libyan crude oil exports:

Figure 4: The Economist, “Relying on Libya” 2.25.2011[ciii]

While European energy security was clearly invested in Libya, arguing that it was the primary motivator for intervention is a hard point to defend. Beginning with the EU’s removal of sanctions in 2004, Libya was already well integrated into international oil markets. The UK’s British Petroleum, Italy’s ENI, and Spain Repsol all had billions of dollars in contracts already in place[civ]. Had oil interests been the sole determinant for guiding foreign policy in Libya, Europe would have simply waited for Qaddafi to crush the opposition. Given the “low tactical capacity of opposition forces”[cv] it would not have been long before Libyan oil was back on the market. Instead, the Libyan campaign shocked oil markets.

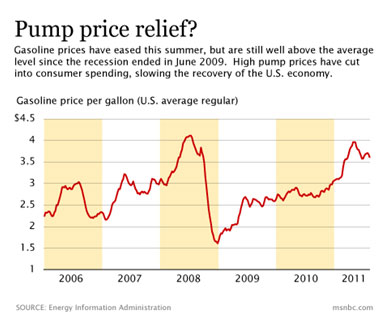

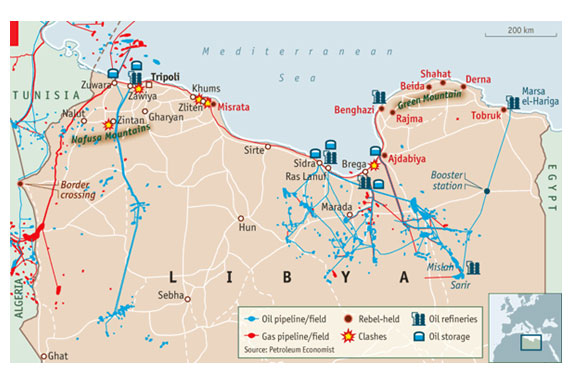

For only the second time since 1975, the spike in oil prices (see Pump price relief?) forced the U.S. to release oil from its strategic stockpile reserves this past summer[cvi]. The spike in oil prices hurt vested oil companies like ENI, Total SA, and Repsol[cvii]. As Figure 5 illustrates, loyalist forces severely damaged Libyan oil infrastructure by systematically targeting energy facilities. In a “scorched earth” policy they strategically targeted these locations in order to block oil production, knowing that this would take Libyan oil off the market for an indeterminate period of time. Extensive damage was done to the most productive oil refinery of Ras Lanuf[cviii], accounting for near 60% of the country’s national refining capacity[cix]. Libyan oil production currently sits at a fraction of where it once stood[cx], and it is widely reported that output could take years before it reaches pre-intervention levels[cxi]. These tremendous setbacks to the Libyan hydrocarbon industry indicate that while oil was probably not the most important factor for intervention, long-term European energy security was partially invested in Libyan crude oil exports.

Figure 5: The Economist, “The colonel is running on empty” 6.16.2011[cxii]

IV. OPERATIONAL FEASABILITY

While military intervention is never an ideal political solution, certain factors can make a purely air-enforced intervention more operationally feasible. In the case of Libya, favorable ground conditions as well as a local partnership with the rebels on the ground ensured that civilian casualties were significantly minimized. Moreover, since the NTC’s administrative leadership was organized and united by mid-March, coalition forces could count on a legitimate political partner during the highly volatile transitional stages. This section will review what made the Libyan case operationally suited for enforcing UNSCR 1973.

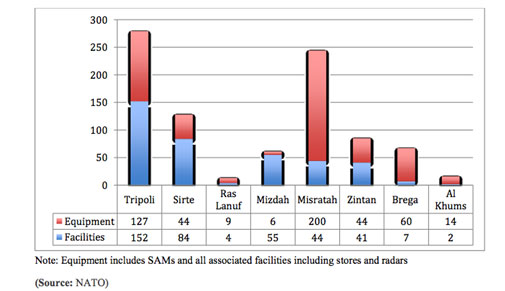

Figure 6: NATO’s targeting of Qaddafi’s equipment

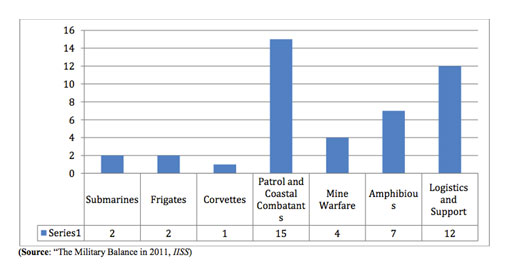

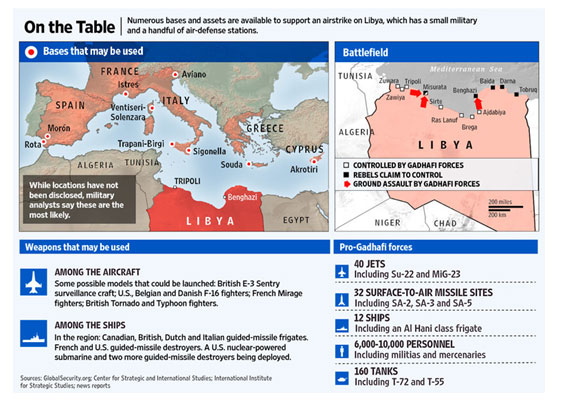

At only 6.4 million people[cxiii], Libya’s population is very small for how vast its territory is. Libya has the 4th lowest population density in Africa, and the 10th lowest in the world[cxiv]. The CIA World Fact Book describes the expansive Libyan territory as “mostly barren”, with “flat to undulating plains, plateaus, and depressions”[cxv]. These topographical features represent the best possible landscape conditions for calculated airstrikes. Since major air bases are geographically removed from large city centers like Tripoli and Benghazi, preemptively bombing these targets proved to be relatively easy for coalition partners[cxvi]. Notice that the Figure 6 above shows the coalition’s efforts to neutralize the ground exchange by targeting military capital in the first few weeks of the campaign. Next, compare the Figure 7 below with Table 1 (see section: Multilateral Coalition, p.12), and it becomes clear that the Libyan Navy’s pre-war resources were no-match for the coalition forces’ naval contributions.

Figure 7: Libyan Navy statistics pre-War 2011

The table found above (On the Table) was released in anticipation of NATO’s enforcement of UNSCR 1973. It further proves that Qaddafi’s forces posed no serious threat to the combined military capabilities of the coalition. His 40 outdated jets and 12 ships were both quantitatively and qualitatively inferior to the 195 aircrafts and 18 ships that the coalition had pledged by the beginning of April[cxvii]. Yet, where Qaddafi’s forces lacked sea and airpower, they made up for in ground control. In addition to the 160 tanks at their disposal, the Qaddafi forces enjoyed greater military training and organization than the rebels. But due to Qaddafi’s paranoia of the threat from coup d’états, Libya lacked a serious long-term investment in military infrastructure:

Historically, Libya invested in equipment and facilities rather than sound manpower infrastructure, and support base. This seriously hurt military effectiveness and morale, particularly after a decisive defeat in Chad at the hands of lightly armed Chadian forces. Its forces further declined in quality, and any reform attempts were token gestures with negligible impact on overall force quality, and certainly not resembling the scale of structural and ideological change needed for army-wide impact. [CSIS, The Libyan Uprising, 6.20.2011]

The fact that 25,000 mercenaries have been reported to be operating in Libya is a testament to the overall weakness of pro-Qaddafi forces[cxviii]. Because could no longer rely on ideological support, he became dependent on hired guns to fight in his name. Since UNSCR 1973 strictly prohibited NATO from sending in ground forces, it relied heavily on coordination with the Libyan rebel opposition and Special Forces. This partnership proved to be very effective in swiftly striking key military facilities before they were at risk of being used against the Libyan people (see Figure 6). The relative inferiority of the loyalist forces was only compounded by the practically ideal demographic conditions on the ground.

While some have argued that Libya’s past tribal influence during its colonial years makes it susceptible to falling into sectarian divide, we find these concerns to be rather anachronistic. Qaddafi’s forty-two years left Libya’s tribes completely stripped of political power[cxix]. Modernizing economic forces like labor mobility and specialization further diminished tribal influences in Libyan society. With an urbanization rate of 78%, Libyans are largely disconnected from their tribal history and it is not a primary means of identification[cxx]. Similarly, with a median age of 24.5[cxxi], there is a generational disconnect from tribalism since most Libyans have no memory of when it was prevalent. Moreover, the homogeneity of the population makes it extremely unlikely that religious and ethnic factions can absorb the momentum of the revolution. Libya has a largely uniform demographic breakdown with; 97% of its people being either Arabs or Berbers[cxxii]; 95% of the population speaking Arabic[cxxiii], and 97% of Sunni Muslim faith[cxxiv]. Qaddafi helped to enforce the religious homogenization of his former subjects by adopting a law that had limited one church per each foreign denomination per city[cxxv].

Qaddafi saw all extremist elements outside of his regime as potential threats to his power. He responded with heavy state crackdown on Islamic extremists, thereby virtually exterminating their influence in all populated regions of Libya[cxxvi]. The few parts of the country that might be responsive to extremist ideology are the least populated, educated, and developed places of the desert. In general, Libya is more educated and secular than its neighbors—making it much less susceptible to the influence of Islamic extremism[cxxvii]. With a population that has a literacy rate of 86.8%[cxxviii], the highest Human Development Index (HDI) on the African continent[cxxix], and a largely “internet savvy” youth[cxxx], there is little evidence to suggest that extremist elements can hijack the revolution.

The NTC and the rebel opposition have been clear since the beginning of the revolution that they want a unified Libya with Tripoli as its capital. While there have been reports of the dueling legitimacies disagreeing over the process in which the country’s political order will be rebuilt[cxxxi], the NTC has laid out a smart political roadmap towards democracy that incorporates the disarming of brigades in exchange for educational benefits and political participation[cxxxii]. NTC officials studied closely the faults of the Iraq political process, and are ensuring that political inclusion is central to the reconciliation that will ensue. Their hope is to continue to build on the current of unified Libyan popular support. The aforementioned Libyan popular opinion poll reminds them that: “98% of Libyans do not favor a sectarian divide. In addition, 94% said that Al-Qaeda had not played any role in the 17th of February revolution, and 91% thought it impossible for Al-Qaeda to play any political role in the new Libya.”[cxxxiii] Lastly, the NTC has taken many precautions that stem from the lessons from Iraq and the sectarian divide that arose after inclusion was not made a priority in the political system. By encouraging pluralism in a very homogeneous state, they are protecting themselves from the mistakes seen in previous interventions.

V. CONCLUDING STATEMENTS

It’s far too early to declare Libya “Mission Accomplished”. While Qaddafi supporters no longer pose a threat to the transitional government, Libyans must now manifest their democratic aspirations. Having absolutely no political institutions to build-up from could be seen as both a blessing and a curse. Although this limits the footprint of the former regime on Libya’s future, many question whether the NTC can build transitional bodies that encourage stability and have mechanisms for accountability. Similarly, the massive oil and natural gas endowment can act as either a great strength or a great weakness. In the past countries blessed with the “oil curse” have been reduced to failed states as there is a tendency for the natural resource to be used as a political tool used by demagogues. Conversely, if Libya learns from Norway’s history and outlaws political campaign promises over oil, its exports can feed into a long-term state sovereign wealth fund and lead to development and a diversification of the economy. We have yet to see if Libya can succeed in becoming a democratic model for the Arab world, but without the advent of intervention the possibility would have been inconceivable and the international community would have permitted a massacre.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[i] “PressTV – 13 more mass graves found in Libya” <http://www.presstv.ir/detail/199302.html >. Press TV. 15 September 2011.

[ii] “Civil Society: UN General Assembly should suspend Libya’s UN Human Rights Council membership.” Defending Human Rights Worldwide. Human Rights Watch, 24 Feb. 2011. Web. 18 Sept. 2011. <http://www.hrw.org/print/news/2011/02/24/civil-society-un-general-assembly-should-suspend-libya-s-un-human-rights-council-mem>.

[iii] “Libyan Crackdown ‘Escalates’ – UN” <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-12576427>. BBC News. 25 February 2011.

[iv] Cotler, Irwin, and Jared Genser. “Libya and the Responsibility to Protect.” The New York Times 28 Feb. 2011, sec. Opinion: 2. NYTimes.com. Web. 18 Sept. 2011.

[v] Fadel, Leila. “Libyan rebels call for foreign military help.” The Sydney Morning Herald [Sydney, Australia] 3 Mar. 2011: 2. smh.com.au. Web. 18 Sept. 2011.

[vi] Tran, Mark. “Gaddafi troops pound Libya rebels out of Ras Lanuf.” Guardian. (2011): n. page. Web. 23 Oct. 2011. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/mar/10/ras-lanuf-rebel-retreat-libya>.

[vii] “Updated: Libyan fighter jets arrive in Malta” The Times of Malta. [Malta] 21 Feb. 2011.

<http://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20110221/local/two-libyan-fighter-jets-arrive-in-malta-two-helicopters-land.351349>

[viii] McGreal, Chris. “Gaddafi’s army will kill half a million warn Libyan rebels.” The Guardian [UK] 12 Mar. 2011: 2. Guardian News. Web. 18 Sept. 2011.

[ix] “UN chief calls for ceasefire in Libya” Al Jazeera. [Libya] 16 Mar. 2011. <http://english.aljazeera.net/news/africa/2011/03/201131614230683317.html>

[x] Walt, Vivienne. “Gaddafi’s Son: Last Gasp of Libya’s Dying Regime?” Time. 21 Feb. 2011. <http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2052842,00.html>

[xi] Stalinsky, Steven. “Gaddafi calls out ‘greasy rats’ and ‘foreign agents’” National Review. 22 Feb. 2011. <http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/260380/gaddafi-calls-out-greasy-rats-and-foreign-agents-steven-stalinsky>

[xii] “Responsibility to Protect: The lessons of Libya.” The Economist. 19 May 2011: 2. Print.

[xiii] “Libya protests: defiant Gaddafi refuses to quit” BBC. 22 February. 2011. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-12544624>

[xiv] “Libya uprising – Thursday 10 March” The Guardian. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/blog/2011/mar/10/libya-uprising-gaddafi-live#block-15>

[xv] Fahim, Kareem; Kirkpatrick, David D. “Qaddafi Massing Forces in Tripoli as Rebellion Spreads“ The New York Times. 23 February. 2011. <http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/24/world/africa/24libya.html?_r=1&hp=&pagewanted=all>

[xvi] Cole, Juan. Informed Comment. 22 August. 2011. <http://www.juancole.com/2011/08/top-ten-myths-about-the-libya-war.html>.

[xvii] “Qaddafi supporters attack mosque in Zawiya with anti-aircraft missile” Feb 17th News. 24 February. 2011. <http://feb17.info/news/qaddafi-supporters-attack-mosque-in-zawiya-with-anti-aircraft-missile/>

[xviii] “Libya: Gaddafi tanks and planes attack rebel towns” BBC News Africa. 8 March. 2011. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-12673956>

[xix] “How rebels held Misrata” Associated Press. 4 May. 2011 <http://feb17.info/news/how-rebels-held-misrata/>

[xx] “Muammar Gaddafi war crimes files revealed” The Guardian. 18 June. 2011. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/jun/18/muammar-gaddafi-war-crimes-files>

[xxi] Western, Jon. “Protecting States or Protecting Civilians.” The Massachusetts Review. 52.2 (Summer 2011): 348-357. Print.

[xxii] “Libya – 130 soldiers executed” News 24. 23 Feb. 2011. <http://www.news24.com/Africa/News/Libya-130-soldiers-executed-20110223>

[xxiii] “Libya: Benghazi about to fall… then came the planes” The Telegraph. 20 March. 2011. <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/libya/8393843/Libya-Benghazi-about-to-fall…-then-came-the-planes.html>

[xxiv] “Benghazi on the Hill” Foreign Policy. 18 June. 2011. <http://lynch.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2011/06/18/benghazi_on_the_hill>

[xxv] “Libya and the Responsibility to Protect” The Brookings Institution. 16 June. 2011. <http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Files/events/2011/0616_libya_responsibility/20110616_libya_responsibility.pdf>

[xxvi] “Analysis: Gaddafi will fight to the bitter end” ABC News. 28 Feb. 2011. <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-02-22/analysis-gaddafi-will-fight-to-the-bitter-end/1953380>

[xxvii] “Muammar Gaddafi says he will die a martyr rather than quit” The Guardian. 22 Feb. 2011. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/feb/22/muammar-gaddafi-libyan-tv-martyr>

[xxviii] “Hoard of Cash Lets Qaddafi Extend Fight Against Rebels” The New York Times. 9 March. 2011. <http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/10/world/africa/10qaddafi.html?_r=2&hp>

[xxix] “Challenges ahead as rebels reach Tripoli” The Financial Times. 22 August. 2011. <http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/c3e3ee3e-cc40-11e0-9176-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1ZsG1woPy>

[xxx] “Libya Update: The Violence of An Unraveling Regime [On Qaddafi’s Speech]” Jadaliyya. 21 Feb. 2011. <http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/707/libya-update_the-violence-of-an-unraveling-regime_>

[xxxi] “Defections From the Libyan Regime” The Wall Street Journal. 23 Feb. 2011. <http://blogs.wsj.com/dispatch/2011/02/23/defections-from-the-libyan-regime/>

[xxxii] “Obama’s Libya speech: Full text as delivered” Politico. 28 March. 2011. <http://www.politico.com/news/stories/0311/52093.html>

[xxxiii] “NATO says preconditions fulfilled for actions against Libya” Xinhua News Agency. 19 March. 2011. <http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/world/2011-03/19/c_13786742.htm>

[xxxiv] “Rebels in east Libya set up crisis committee” Reuters News Agency. 5 March. 2011. <http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/03/05/libya-east-council-idAFLDE7240EP20110305>

[xxxv] “UN assembly recognizes NTC” English.Libya.Tv. 16 September. 2011. <http://english.libya.tv/2011/09/16/un-assembly-recognizes-ntc/>

[xxxvi] “The rebellion’s leaders: Good intentions, fragile legitimacy” The Economist. 27 August. 2011. <http://www.economist.com/node/21526958>

[xxxvii] “Voice of the Libyan Street” National Transitional Council. Sourced from: Research and Consultation Center, Garyounis University, Benghazi <http://www.ntclibya.com/InnerPage.aspx?SSID=31&ParentID=0&LangID=1>

[xxxviii] “130 Libyan soldiers executed for mutiny” PressTV. 24 Feb. 2011. <http://www.presstv.ir/detail/166757.html>

[xxxix] “Top Ten Ways that Libya 2011 is Not Iraq 2003” Informed Comment. 22 March. 2011. <http://www.juancole.com/2011/03/top-ten-ways-that-libya-2011-is-not-iraq-2003.html>

[xl] “Gaddafi’s speech: Decoding a tyrant’s words” National Post. 22 Feb. 2011. <http://news.nationalpost.com/2011/02/22/gaddafis-speech-decoding-a-tyrant%E2%80%99s-words/>

[xli] “Eastern Libyans believe in national unity, distrust AU and Turkish mediation, survey reveals” English.Libya.TV. 25 April. 2011. <http://english.libya.tv/2011/04/25/eastern-libyans-believe-in-national-unity-distrust-au-and-turkish-mediation-survey-reveals/>

[xlii] “Benghazi rebels plead for Libya air strikes as Gaddafi forces advance” The Guardian. 19 March. 2011. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/mar/19/gaddafi-forces-battle-for-benghazi>

[xliii] “Weak and Crippled by Rivalry” The New York Times: Opinion Pages. 16 March. 2011. <http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2011/03/16/what-can-arab-leaders-do-about-libya/weak-and-crippled-by-rivalry>

[xliv] “Libya crisis: too late for UN military intervention?” The Guardian Blog. 23 Feb. 2011. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/blog/2011/feb/23/libya-crisis-gaddafi-un-military-intervention>

[xlv] Nordland, Rod. “In Libyan Rebel Capital, Shouts of Thanks to America and the West” The New York Times. 28 May. 2011. <http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/29/world/africa/29benghazi.html?_r=2&ref=world>

[xlvi] “Security Council authorizes ‘all necessary measures’ to protect civilians in Libya” UN News Centre. 17 March. 2011. <http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=37808>

[xlvii] “Libya: Nigeria votes in favour of no-fly resolution” Reuters News Agency. 18 March. 2011. <http://www.vanguardngr.com/2011/03/libya-nigeria-votes-in-favour-of-no-fly-resolution/>

[xlviii] “UN security council resolution 1973 (2011) on Libya – full text” The Guardian. 17 March. 2011. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/mar/17/un-security-council-resolution>

[xlix] “Rebels: Assaulted In Spite of Gaddafi ‘Cease Fire’” Time. 18 March. 2011. <http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2060366,00.html>

[l] “Gadhafi blasts ‘crusader’ aggression after strikes” MSNBC News. 19 March. 2011. <http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/42164455/ns/world_news-mideastn_africa/?gt1=43001#.TqDt5HEi7hE>

[li] “Gaddafi Forces Reject Rebels’ Cease-Fire” Reuters. 1 April. 2011. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/04/01/gaddafi-ceasefire-rebels-libya-news_n_843791.html>

[lii] “Libya: Gaddafi has accepted roadmap to peace, says Zuma” The Guardian. 10 April. 2011. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/apr/10/libya-african-union-gaddafi0-rebels-peace-talks>

[liii] “Libya Rebels Reject Cease-Fire That Doesn’t Oust Qaddafi” Bloomberg Businessweek. 11 April. 2011. <http://www.businessweek.com/news/2011-04-11/libya-rebels-reject-cease-fire-that-doesn-t-oust-qaddafi.html>

[liv] “The Future of Libya: A View from the Opposition” The Brookings Institution. 12 May. 2011. <http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Files/events/2011/0512_libya/20110512_libya.pdf>

[lv] “Gaddafi offers truce but not exit” Al Jazeera. 30 April. 2011. <http://english.aljazeera.net/news/africa/2011/04/201143021326235617.html>

[lvi] “Libyan rebel forces reject Muammar Gaddafi’s ceasefire offer” The Guardian. 30 April. 2011. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/apr/30/libyan-rebels-reject-gaddafi-offer>

[lvii] “Gaddafi insists on truce not departure” Albawaba News. 31 May. 2011. <http://www.albawaba.com/main-headlines/gaddafi-insists-truce-not-departure-375963>

[lviii] “Report of the International Commission of Inquiry to investigate all alleged violations of international human rights law in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya” Human Rights Council. 1 June. 2011. <http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/17session/A.HRC.17.44_AUV.pdf>

[lix] “Libya: Coalition divided on arming rebels” BBC News Africa. 29 March. 2011. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-12900706>

[lx] “Security Council Approves ‘No-Fly Zone’ over Libya, Authorizing ‘All Necessary Measures’ to Protect Civilians, by Vote of 10 in Favour with 5 Abstentions” UN Department of Public Information. 17 March. 2011. <http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2011/sc10200.doc.htm>

[lxi] Rogin, Josh. “Over 200 Arab groups call for Libya no-fly zone” Foreign Policy. 25 Feb. 2011. <http://thecable.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2011/02/25/over_200_arab_groups_call_for_libya_no_fly_zone>

[lxii] “UN Security Council Imposes Sanctions Against Libya’s Qaddafi” Bloomberg Businessweek. 27 Feb. 2011. <http://www.businessweek.com/news/2011-02-27/un-security-council-imposes-sanctions-against-libya-s-qaddafi.html>

[lxiii] “Libyan regime ‘lost legitimacy’—Arab League” Agence France-Presse. 13 March. 2011. <http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/breakingnews/world/view/20110313-325099/Libyan-regime-lost-legitimacyArab-League>

[lxiv] “GCC: Libya regime lost legitimacy” Al Jazeera. 11 March. 2011. <http://english.aljazeera.net/news/middleeast/2011/03/2011310211730606181.html>

[lxv] Shaheen, Kareem.“GCC wants no-fly zone over Libya” The National. 8 March. 2011. <http://www.thenational.ae/news/uae-news/politics/gcc-wants-no-fly-zone-over-libya>

[lxvi] Freeman, Colin. “Libya: Arab League calls for United Nations no-fly zone” The Telegraph. 12 March. 2011. <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/libya/8378392/Libya-Arab-League-calls-for-United-Nations-no-fly-zone.html>

[lxvii] “OIC plans to support no-fly zone over Libya” Gulf News. 16 March. 2011. <http://gulfnews.com/news/gulf/saudi-arabia/oic-plans-to-support-no-fly-zone-over-libya-1.778130>

[lxviii] “Ask a Think Tank: Brookings’ Shadi Hamid on Arab Support in Libya” Think Tanked. 21 March. 2011. <http://www.thinktankedblog.com/think-tanked/2011/03/ask-a-think-tank-brookings-shadi-hamid-on-arab-support-in-libya.html>

[lxix] “Huge majority of Arabs want Gaddafi removed from power” The Doha Debates. 18 May. 2011. <http://www.thedohadebates.com/news/item.asp?n=12791>

[lxx] “Libya: Nigeria votes in favour of no-fly resolution” Reuters. 18 May. 2011. <http://www.vanguardngr.com/2011/03/libya-nigeria-votes-in-favour-of-no-fly-resolution/>

[lxxi] “Security Council Approves ‘No-Fly Zone’ over Libya, Authorizing ‘All Necessary Measures’ to Protect Civilians, by Vote of 10 in Favour with 5 Abstentions” UN Department of Public Information. 17 March. 2011. <http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2011/sc10200.doc.htm>

[lxxii] “Libya: Africa’s Rights Body Should Act Now” Human Rights Watch. 25 Feb. 2011. <http://www.hrw.org/news/2011/02/25/libya-africa-s-rights-body-should-act-now>

[lxxiii] St, John (p.229) R. B. Libya: From Colony to Independence. Oxford: Oneworld, 2008. Print.

[lxxiv] “Gaddafi calls in favours from Africa” The Financial Times. 27 March. 2011. <http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/488d4fc6-5898-11e0-9b8a-00144feab49a.html#axzz1eJ9eTg6H>

[lxxv] “The Arab Spring: Hopes and Challenges” The Brookings Institution. 6 June. 2011. <http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Files/events/2011/0606_juppe/20110606_arab_spring_juppe.pdf>

[lxxvi] “Eastern Libyans believe in national unity, distrust AU and Turkish mediation, survey reveals” English.Libya.TV. 25 April. 2011. <http://english.libya.tv/2011/04/25/eastern-libyans-believe-in-national-unity-distrust-au-and-turkish-mediation-survey-reveals/>

[lxxvii] Polgreen, Lydia. “Qaddafi, as New African Union Head, Will Seek Single State” The New York Times. 2 Feb. 2011. <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/03/world/africa/03africa.html>

[lxxviii] Gettlemen, Jeffrey. “Libyan Oil Buys Allies for Qaddafi” 15 March. 2011. <http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/16/world/africa/16mali.html>

[lxxix] Landay, Jonathan S. “Despite reluctance, U.S. could be forced to act in Libya” 2 March. 2011. <http://www.mcclatchydc.com/2011/03/02/109737/despite-reluctance-us-could-be.html>

[lxxx] “Protection of Civilians – France ONU” <http://www.franceonu.org/spip.php?article4091>

[lxxxi] “Security Council Approves ‘No-Fly Zone’ over Libya, Authorizing ‘All Necessary Measures’ to Protect Civilians, by Vote of 10 in Favour with 5 Abstentions” UN Department of Public Information. 17 March. 2011. <http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2011/sc10200.doc.htm>

[lxxxii] “2011 military intervention in Libya: Forces Committed” 8 November. 2011. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2011_libyan_intervention#Forces_committed>

[lxxxiii] “Humanitarian aid in Libya: how much has each country donated?” The Guardian. 22 Aug. 2011. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/2011/aug/22/libya-humanitarian-aid-by-country>

[lxxxiv] Hamid, Shadi & Steven Brooke. “Promoting Democracy to Stop Terror, Revisited” Stanford University’s Hoover Institute. 1 Feb. 2011. <http://www.hoover.org/publications/policy-review/article/5285>

[lxxxv] Slim, Randa. “U.S. Intervention in Libya: Shifting the Narrative in U.S.-Arab relations” The Huffington Post. 23 March. 2011. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/randa-slim/us-intervention-in-libya-_b_839581.html>

[lxxxvi] Stewart, Phil. “U.S. urges Yemen transition, no aid cut-off-Pentagon” Reuters. 5 April. 2011. <http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/04/05/us-yemen-usa-pentagon-idUSTRE7346V720110405>

[lxxxvii] “Oman” U.S. State Department. 7 March. 2011. <http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/35834.htm>

[lxxxviii] “U.S. Backs Bahrain Royalty, Varying Playbook on Revolt” The Wall Street Journal. 1 March. 2011. <http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703409904576174830538031352.html>

[lxxxix] “Egypt unrest: Obama increases pressure on Mubarak” BBC News. 5 Feb. 2011. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-12371479>

[xc] Shibley, Telhami. “2010 Annual Arab Public Opinion Survey” The Brookings Institute. June 2010. <http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Files/rc/reports/2010/0805_arab_opinion_poll_telhami/0805_arabic_opinion_poll_telhami.pdf>

[xci] “Libya Action in U.S. National Interest” The Brookings Institute & Politico. 28 March. 2011. <http://www.brookings.edu/opinions/2011/0328_libya_telhami.aspx>

[xcii] Korb, Lawrence. “Obama helps U.S. interests In Libya” Politico. 23 March. 2011. <http://www.politico.com/news/stories/0311/51804_Page2.html>

[xciii] Hamid, Shadi. “Is Intervening in Libya in American Interests?” Democracy Arsenal. 19 March. 2011. <http://www.democracyarsenal.org/2011/03/is-intervening-in-libya-in-american-interests.html>

[xciv] Farah, Douglas. “Harvard for Tyrants” Foreign Policy. 4 March. 2011. <http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/03/04/harvard_for_tyrants>

[xcv] Charara, Walid. “Syria: a Monopoly on Democracy” Le Monde Diplomatique. 11 July. 2011. <http://mondediplo.com/2005/07/11syria>

[xcvi] Terranova, Brian. “Algeria: The Obstacles to Democracy” e-International Relations. 13 Aug. 2011. <http://www.e-ir.info/?p=12285>

[xcvii] Landay, Jonathan S. “Despite reluctance, U.S. could be forced to act in Libya” McClatchy. 2 March. 2011. <http://www.mcclatchydc.com/2011/03/02/109737/despite-reluctance-us-could-be.html>

[xcviii] Knowlton, Brian. “Gates Calls European Mood a Danger to Peace” The New York Times. 23 Feb. 2011. <http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/24/world/europe/24nato.html>

[xcix] Ouali, Aomar. “Nations focus on al-Qaida terror in Sahara Desert “ Associated Press. 7 Sep. 2011. <http://news.yahoo.com/nations-focus-al-qaida-terror-sahara-desert-115938377.html>

[c] Slim, Randa. “U.S. Intervention in Libya: Shifting the Narrative in U.S.-Arab relations” The Huffington Post. 23 March. 2011. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/randa-slim/us-intervention-in-libya-_b_839581.html>

[ci] Leonard, Andrew. “Libya. Oil. War. Is it that simple?” Salon.com. 21 March. 2011. <http://www.salon.com/2011/03/21/the_libyan_oil_war_connection/>

[cii] Abbasov, Namiq. “Energy potential of Libya: How is it essential for the European Energy Security?” Caspian Weekly. 21 October. 2011. <http://en.caspianweekly.org/component/content/article/41-articles/4110-energy-potential-of-libya-how-is-it-essential-for-the-european-energy-security.html>

[ciii] “Libyan Oil: Relying on Libya” The Economist. 25 Feb. 2011. <http://www.economist.com/blogs/dailychart/2011/02/libyan_oil>

[civ] Sanati, Cyrus. “Big Oil’s $50 billion bet on Libya at stake” CNN Money. 23 Feb. 2011. <http://money.cnn.com/2011/02/23/news/international/libya_eni_oil.fortune/index.htm>

[cv] [P.37] Vira, Varun; Anthony H. Cordesman; and Dr. Anthony H. Cordesman. “The Libyan Uprising: An Uncertain Trajectory” Center for Strategic and International Studies. 20 June. 2011. <http://csis.org/files/publication/110620_libya.pdf>

[cvi] Hargreaves, Steve. “Libyan oil could take years to come back” CNN Money. 22 Aug. 2011. <http://money.cnn.com/2011/08/22/markets/libya-oil-production/index.htm>

[cvii] Cole, Juan. “Top Ten Myths about the Libyan War” Informed Comment. 22 Aug. 2011. <http://www.juancole.com/2011/08/top-ten-myths-about-the-libya-war.html>

[cviii] [P.15] Vira, Varun; Anthony H. Cordesman; and Dr. Anthony H. Cordesman. “The Libyan Uprising: An Uncertain Trajectory” Center for Strategic and International Studies. 20 June. 2011. <http://csis.org/files/publication/110620_libya.pdf>

[cix] “Country Analysis Briefs: Libya” U.S. Department of Energy: Energy Information Administration. Feb 2011. <http://www.eia.gov/emeu/cabs/Libya/pdf.pdf>

[cx] Schoen, John W. “Restoring Libyan oil output could take years” MSNBC News. 22 Aug. 2011. <http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/44229170/ns/business-oil_and_energy/t/restoring-libyan-oil-output-could-take-years/#.TrE2xWC4If8>

[cxi] Hargreaves, Steve. “Libyan oil could take years to come back” CNN Money. 22 Aug. 2011. <http://money.cnn.com/2011/08/22/markets/libya-oil-production/index.htm>

[cxii] “The colonel is running on empty” The Economist. 16 June. 2011. <http://www.economist.com/node/18837167>

[cxiii] “World Development Indicators | Data” The World Bank. September 2011. <http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators?cid=GPD_WDI>

[cxiv] “World Population Prospects: the 2008 Revision” The United Nations: Development. 2008. <http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wpp2008/wpp2008_text_tables.pdf>

[cxv] “The World Fact Book: Field Listing: Terrain” Central Intelligence Agency. November 2011. <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2125.html>

[cxvi] [P.18] Vira, Varun; Anthony H. Cordesman; and Dr. Anthony H. Cordesman. “The Libyan Uprising: An Uncertain Trajectory” Center for Strategic and International Studies. 20 June. 2011. <http://csis.org/files/publication/110620_libya.pdf>

[cxvii] [P.20-37] Vira, Varun; Anthony H. Cordesman; and Dr. Anthony H. Cordesman. “The Libyan Uprising: An Uncertain Trajectory” Center for Strategic and International Studies. 20 June. 2011. <http://csis.org/files/publication/110620_libya.pdf>

[cxviii] [P.21] Vira, Varun; Anthony H. Cordesman; and Dr. Anthony H. Cordesman. “The Libyan Uprising: An Uncertain Trajectory” Center for Strategic and International Studies. 20 June. 2011. <http://csis.org/files/publication/110620_libya.pdf>

[cxix] Kurczy, Stephen; Drew Hinshaw. “Libya tribes: Who’s who?” The Christian Science Monitor. 24 Feb. 2011. <http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Backchannels/2011/0224/Libya-tribes-Who-s-who>

[cxx] Frederic Wehrey, “Libya’s Terra Incognito,” Foreign Affairs, February 28, 2011.

[cxxi] “The World Fact Book: Africa: Libya” Central Intelligence Agency. 17 Nov. 2011. <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ly.html>

[cxxii] Gleitz, Chloe. “Regionalism, ethnicity, and tribes in the trial of Libya’s democratic transition” Consultancy Africa Intelligence. 17 Oct. 2011. <http://www.consultancyafrica.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=872:regionalism-ethnicity-and-tribes-in-the-trial-of-libyas-democratic-transition-&catid=60:conflict-terrorism-discussion-papers&Itemid=265>

[cxxiii] “As Libya cheers, questions over brutal Gadhafi death” CTV News. 22 Oct. 2011. <http://www.ctv.ca/CTVNews/TopStories/20111022/libya-transitional-government-liberation-111022/>

[cxxiv] “The World Fact Book: Africa: Libya” Central Intelligence Agency. 17 Nov. 2011. <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ly.html>

[cxxv] “Libya: Country Reports on Human Rights Practices” U.S. Department of State: Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. 4 March. 2002. <http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2001/nea/8273.htm>

[cxxvi] [P.68] Vira, Varun; Anthony H. Cordesman; and Dr. Anthony H. Cordesman. “The Libyan Uprising: An Uncertain Trajectory” Center for Strategic and International Studies. 20 June. 2011. <http://csis.org/files/publication/110620_libya.pdf>

[cxxvii] [P.69] Vira, Varun; Anthony H. Cordesman; and Dr. Anthony H. Cordesman. “The Libyan Uprising: An Uncertain Trajectory” Center for Strategic and International Studies. 20 June. 2011. <http://csis.org/files/publication/110620_libya.pdf>

[cxxviii] “Education for All Global Monitoring report 2010” United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. 2010. <http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/ED/GMR/pdf/gmr2010/gmr2010-annex-04-stat-intro.pdf>

[cxxix] “Libya – African Economic Outlook” African Economic Outlook. 22 June. 2011. <http://www.africaneconomicoutlook.org/en/countries/north-africa/libya/>

[cxxx] Jawad, Rana. “Tripoli celebrates, but on a smaller scale” BBC News. 23 October. 2011. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/mobile/world-africa-15424278>

[cxxxi] Ghannoushi, Soumaya. “Dueling legitimacies in Libya” Al Jazeera: Opinion. 16 Sep. 2011. <http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2011/09/201191471810380175.html>

[cxxxii] “The Future of Libya: A View from the Opposition” The Brookings Institution. 12 May. 2011. <http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Files/events/2011/0512_libya/20110512_libya.pdf>

[cxxxiii] “Eastern Libyans believe in national unity, distrust AU and Turkish mediation, survey reveals” English.Libya.TV. 25 April. 2011. <http://english.libya.tv/2011/04/25/eastern-libyans-believe-in-national-unity-distrust-au-and-turkish-mediation-survey-reveals/>

—

Written by: Francis Ramoin

Written at: University of Washington, Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies

Written for: Kazimierz Poznanski

Date written: 12/2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- To What Extent Was the NATO Intervention in Libya a Humanitarian Intervention?

- The Effect of the Intervention in Libya on the International Debate about Syria

- Obama and ‘Learning’ in Foreign Policy: Military Intervention in Libya and Syria

- Egypt’s Security Paradox in Libya

- Will Armed Humanitarian Intervention Ever Be Both Lawful and Legitimate?

- A Critical Analysis of Libya’s State-Building Challenges Post-Revolution