Figure 1. Office of the District Commissioner, Faisalabad. (23/6/2010, photograph by author)

The story of local government in Pakistan is extraordinary. It is also very important: it explains a lot about Pakistan, and the challenges Pakistan faces in deepening democracy and allocating public goods; but it also explains a lot about local government: about what it is for, how it turns out, and about how you can, and how you shouldn’t, design a system to localise power.

Rarely has such an ambitious scheme as the 2001 Pakistani local government reforms – the “nazim” (mayor) system – ever been attempted, least of all in a developing country. Indonesia’s experiment in devolution around the same time is the only thing that comes close (DSD, 2006). Moreover, rarely has a devolution scheme been so heavily supported by international donor agencies – the Asian Development Bank alone spent over $200 million on supporting the scheme (ADB, 2010) and they were by no means alone. The idea was that this would revolutionise development – by bringing it closer to the people but also, as Shandana Mohmand (in Gelner and Hachhethu, 2008) astutely pointed out, by a neo-liberal rolling back of the role of the State. It didn’t do any of these things.

It was a complicated system but this was the gist of it: Three new layers of local government were introduced. The lowest, the Union Council (or “UC”), was to be the size of just a few villages – a unit far smaller than had ever been previously attempted. UCs were grouped into “tehsils” and tehsils into “districts”. Elections would be non-political and only the lowest – UC – tier would be directly elected. The elected UC nazims would act as the local executive mayor and also form the council of the higher tiers of the system. Most importantly they would form the electorate which would go on to vote for the executive heads of the higher tiers: the tehsil nazims and the district nazim.

Many commentators were upbeat about the prospects for the new system. In 2006 a comprehensive multi-agency study on Pakistani devolution (DSD, 2006) said, “In reality, devolution is undoubtedly a fact of life, it is not plausible to expect any substantial return to a discredited set of institutional arrangements with a proven track record of failure”.

Yet by 2008 the system was already unravelling: the instigator of the system – President Musharraf – was ousted, local government was made a provincial responsibility, and the new provincial governments immediately set out to abolish the system.

From 2009 to 2012 local government existed in a legalistic limbo: the elected officials’ terms having expired they were immediately shown the door; but no new elections were held, nor was any new system introduced. During this state of limbo civil servants were put in direct command of local government – to their delight, but also (for reasons we shall discuss) to the delight of provincial politicians.

Baluchistan immediately abolished local government and went back to the previous, civil-servant-led model. Other provinces are just now finalising arrangements: the newly named Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the Punjab both recently decided upon hybrid systems whereby executive power would be held by civil servants but there would also be (non-party) elections for councils. Meanwhile the situation in Sindh remains the subject of protracted debate.

Overview

The received wisdom is that devolution deepens and strengthens democracy. However, that is not the consensus in Pakistan. It has been well argued by many in Pakistani academia that thus far devolution has largely been used by the military and the bureaucracy as a tool for undermining democracy (Waseem, 2006). The political parties certainly believe that, hence their all-out assault on local government.

Historically this has always been seen as a clash of tiers: the formation of political parties in Pakistan has been strongly tied to provincial identity and the provincial assemblies. In turn various military dictatorships have always tried to circumvent the provinces by forming an alliance between local power, often based in patronage, and the federal state (Waseem, 2000).

What follows is research undertaken by the author in 2009. Two questions were addressed in an attempt to shed some light onto how Pakistan’s new system of local government influenced this struggle between the province and the centre

(1) How does the provision of local public goods by officials at the local level (i.e. via Nazims) differ from the provision of local public goods by officials at the provincial level? Which is the preferable vehicle for service delivery?

(2) How does the development of democracy, and the role of politicians, differ between the two tiers? Can they coexist, and why are they in conflict?

In response to the first question, it can be suggested that there were material advantages to development spending being allocated by local governments over provincial governments. Service delivery certainly appears to have been more equitable and the role of provincial and national politicians in deciding who benefits from development aid was limited. However it is not quite as black-and-white as to say that the latter consequence was universally beneficial: in a country where the selection of development projects is such a vital issue it is surely legitimate to give political parties, and their agents national politicians, a role in it.

Which brings us to the second question: it appears that the political cadre have no interest in making a local layer work. This is not entirely unreasonable: it does seem that this system made no meaningful attempt to deepen democracy.

The question as to wether devolution and democracy always have to be in conflict in Pakistan is more interesting, and it is a question as to what the role of a national Pakistani politician should be. Are the best interests of local people best served if national politicians take a keen interest in their affairs or if they stay out of it and concentrate on national issues? This is not a rhetorical question, and we will discuss it in detail.

Method and theory – general

There is a wealth of very strong writing on devolution theory. Most germane to this discussion is the work of Bardhan and Mookerjee (2001), who established a highly persuasive model for the actual effects of devolution in developing countries – and one which is widely accepted (often unwittingly) in Pakistan.

They propose that the lower the level to which power is devolved, the more responsive and equitable service delivery is. This is supported by the majority of other writings on the subject which state, amongst many other positive attributes of devolution, that by empowering the bottom layer you accelerate the processes of democratic development. This point goes back at very least to Stigler (1957) and arguably to Adam Smith (1776).

However, it is Bardhan and Mookerjee’s (2001) caveat which is so interesting. Their persuasive thesis is that if the system of governance is captured by an elite then all these positive effects can be negated; and, crucially, the risk of elite capture is also related to the level to which power is devolved: the lower the level, the greater the risk of elite capture – because when you divide a region into silos you reduce the power of the multitude, and increase the power of the local fief, within each silo. So devolution becomes a gamble: the more you devolve, the more equitable service delivery becomes if it is not captured by elite forces, but the greater the risk that that will happen.

Such is the general understanding of their work. But there is more to it. To explain let us consider a graphical representation of their theory.

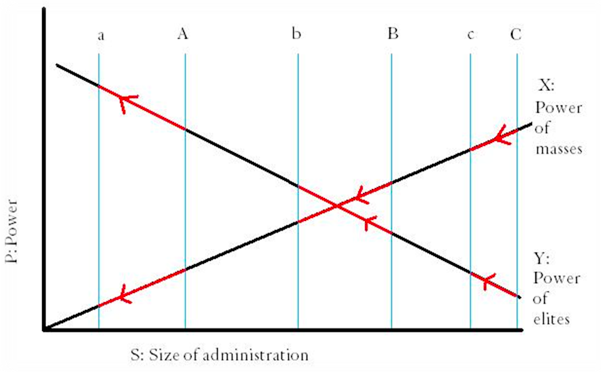

Figure 2. Three generalised devolutions.

We have three entirely general acts of devolution – independent of relative size or geographic location: A to a, B to b and C to c. In this simplification -X=nS and Y= -mS where n and m are functions of the factors outlined in Bardhan and Mookerjee’s work. In other words, in all cases, devolution (the red line) has moved the seat of power to a place where the power of the masses (line X) is lesser and the power of elites (line Y) is greater, making the capture of the system by the elites more likely.

Bardhan and Mookerjee (2001) also contend that under a system of local democracy the power of the mass group is based upon their ability to win elections (formula 8 in their model). Khan et al’s (writing in Waseem ed., 2002) analysis of Bardhan and Mookerjee’s work (their formula 1) suggests that confidence in service delivery is one of the main factors in determining the outcome of elections. We also know that the lower the level to which power is devolved, the more responsive and equitable service delivery is for the mass group.

This is not a contradiction, it just means that whilst X=nS (the smaller the administration, the lesser the power of the mass), one of the factors that makes up that function “n” is how much devolution there is (Geddes (1994) describes essentially the same concept as “insulation”). Of course this is a simplification as n is a composite of many factors.

Let us now revisit our generalised three devolutions after some considerable time has passed.

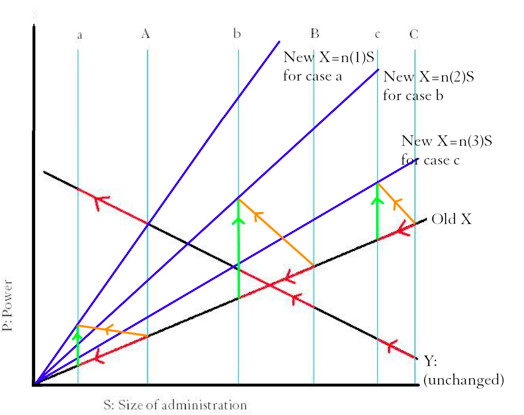

Figure 3. Generalised devolutions some time later.

One could argue that in case a (the most devolved) the fact that service delivery is more equitable and responsive has increased the masses’ ability to win elections; there is therefore a new value of n – let’s call it n(1) – in the formula X=nS and this new n(1) is a much stronger function. There are also new ‘n’s – call them n(2) and n(3) for cases b and c.

This would suggest that as well as the short term effects of devolution (red line) described by Bardhan and Mookerjee, their model also implicitly suggests a long-term effect (green line). The overall effect (orange line) is not always necessarily positive but depends upon the relative strength of these forces.

Whether or not it actually is positive or negative depends upon the other factors: these are generalised cases, these lines could be at any height and could have any gradient, depending upon the specifics of the case and a host of other factors (they may not even be linear). However the argument is that, contrary to popular interpretation, it is implicit in Badhan and Mookerjee’s own work that the effect of devolution is not necessarily negative.

Method and theory – Pakistan

Mohammad Waseem’s (1994) study of the 1993 elections describes the Pakistani electoral landscape primarily in terms of “big men” or brokers who operate large banks of “hundreds or thousands” of votes. In the crudest examples they gain control over this number of voters through bribes, murders and intimidation. In more sophisticated strategies, they gain control as a quid-pro-quo for providing services of access-to, and mediation-with, the state: patronage. They trade these vote banks with the political parties in exchange for, in some instances, money and more generally local public goods which further enhance their reputation and access. There is an economy of patronage in which public goods are the primary currency.

To determine if this was still the case, I conducted a series of formal and informal interviews with politicians, civil servants, journalists and academics, during three weeks in June 2010 in Pakistan, primarily in Faisalabad, Lahore and Islamabad. This created some 14,000 words worth of short hand notes.

Figure 4: Map of Pakistan available under creative comms licence from World of Maps. Islamabad, the federal capital, is marked by a star in the (red) capital territory. Lahore is the state capital of the (green) Punjab, Pakistan’s most populous and economically important province. Fasalabad is due west of Lahore, and is one of the largest cities in the industrial north of the Punjab.

The original intention was to use this to form the basis of a more qualitative, ethnographic, approach to investigating the question – but lacking, at that time, the requisite background I did not approach the task in a particularly structured way – and given the sensitivities involved many interviewees did not want to be linked to the information they gave me. These interviews therefore should merely be taken as deep background, and as an acknowledgement that what follows was influenced by many fascinating conversations with many brilliant and candid people – a list of whom appear in the back.

Waseem updated his 1993 study with regards to the 2002 elections (2006) in which he delved more deeply into issues of mobilization and seduction of individual voters based upon horizontal groupings: be they religious, ethnic, kinship or ideological. He still concludes that all the major parties operated as grand patronage networks – albeit devolution has now introduced a second patronage network in competition with the first.

Wilder (1999) also based his analysis primarily on the 1993 elections. He focussed his research on the influences on individual choice, concluding that party identification is the strongest determining factor – largely trumping the force of biraderi other horizontal groupings. Party identification is partly, and increasingly, based on ideology and service delivery; but the main driver is patronage, which in turn is linked to development spending. So whilst coming at the question from different angles, Waseem and Wilder conclude in agreement – a conclusion shared by such other studies as there are (Yusufzai, 1999).

The consequence of this approach to democracy is that development funding, always a major issue in developing countries, becomes a matter of electoral survival. The Pakistani approach to this, which does at least allow for some transparency, is a form of legalised pork-barrel politics whereby provincial politicians are given pots of money to spend on development at their discretion. Provincial politicians also play a key role in deciding spending priorities for the provincial government’s main development budget. Thus they effectively had a monopoly on the provision of local public goods until the introduction of devolution (Zadai, 1999). Now they have it once again.

Of course this suits them down to the ground, and any non-partisan system of local government is going to be a threat to the development of political parties – but parties feel that devolution is always a threat as at the local level they would be out-competed by local elites in any instance. The hope of democrats within the main political parties is that if power over the provision of public goods can be concentrated at a high enough level for local elites to be locked out, then maybe Pakistani democracy can develop and mature – and maybe MPs can start to control the local elites rather than the local elites controlling MPs. If, in the meantime, that means elected provincial politicians taking on significant powers of patronage themselves, then that is a price they are willing, nay eager, to pay. (Waseem and Burkhi 2002, Cheema 2010, Zadai 1999)

In terms of analysing how this can be measured, I owe a huge amount to the work of Ali Cheema, Shandana Mohmand and others at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (Cheema and Mohmand, 2006).

What follows is a study into an area which had not so far been examined; the budgets of the city district of Faisalabad were scrutinised to determine, spatially, where the money had been going over the last ten years, and to draw out comparisons between characteristics of the system during the years when local government dominated, with those of the system period in which the province was dominant.

The case study: Faisalabad

Faisalabad was chosen as the area for the UK’s DfID (Department for International Development) to pilot a Strategic Policy Unit (SPU). This unit (initially funded and enabled by DfID but locally staffed and now entirely locally owned) was envisaged as an appendage of the devolved local government which would provide budgetary analysis and strategic advice. One of the most valuable things the SPU did is to greatly increase the transparency of local government finances. They performed detailed analyses, undertaking a series of case studies – also publicly available on their website – and conducting an in-depth investigation into how much was spent by third parties and the provincial government between 2001 and 2005. Crucially they made large amounts of the raw data from these investigations available for further study.

Faisalabad was thus chosen because of the availability of the data – without which it would have been difficult to conduct a meaningful study. Although no city is “typical” Faisalabad is thought to be reasonably representative of large cities of the northern Punjab. However of course the Heisenberg Uncertainty principle applies even more strongly to governments than it does to atomic particles – the act of measurement itself influences behaviour, and politicians and civil servants behave very differently when they know somebody is watching.

There were significant changes of format in the data between 2001-5 and 2005-7, after 2005 the data becomes patchy, and after 2007 the data stops entirely. Moreover, conducting a spatial analysis required a certain amount of detective work as the delimitation of political boundaries is problematic and incomplete.

To this we must add yet further caveats for a multitude of reasons. There is no benchmark data, many of the most important public goods (such as schools and hospitals) provide “spillover” good to neighbouring areas, it is virtually impossible to distinguish spending by type, there is not a one-to-one mapping between the units (such as councils) that matter to local politicians and those (such as polling stations) that matter to provincial ones, and there is a (surprisingly vague) difference in areas of responsibility between the tiers.

I would therefore be reluctant to say anything was proved, but the data seemed to suggest the following.

The data

The interpretation presented here tend to support the conclusions of Ali Cheema and Shandana Mohmand (2006), who have done extensive amount of work on other tiers of the same system.

Firstly, development spending administered by the districts (local level) appears to be more equitable and more reliable than development spending administered by the province.

To analyse this data the period from 2001 to 2005 was used, as it is only here that we have uninterrupted data of sufficient detail. Every piece of development spending in the four years was categorised by Union Council and by source of funding: provincial or district. In this time the district spent 1,840 million rupees whilst the province spent 340 million rupees. A Gini coefficient[1] analysis on the results found that the Gini coefficient for district spend between Union Councils over the 4 years is 0.58, for provincial spend it is 0.86. A Gini coefficient analysis on the year on year changes in spending per Union Council found that district spend had an average year-on-year Gini coefficient of 0.39 whereas provincial spend averaged 0.68.

Analysis: it would seem that provincial politicians have a preference for a few large schemes whereas local government leads to a more diffuse approach. From personal experience I know that the bureaucracy has a distaste for this kind of approach – they regard it as “frittering away” budgets.

It appears to be a universal bureaucratic desire to build impressive edifices and this also satisfies the requirements of National Politicians to have one or two marquee projects which they can be personally associated with for electoral purposes. With a tier of local politicians each clamouring for their share of the developmental pie such projects become harder to realise. And while bureaucrats may bemoan what they see as a lack of strategic direction to development this does mean individual areas are less likely to be overlooked.

Anecdotally, this also has consequences for the kinds of development that are prioritised. Under devolution you get a concentration on schemes such as sanitation, local roads, and water facilities that provide very concentrated benefits to specific villages. Under civil servant, or national, control you get schemes such as flyovers, but also schools and hospitals, which provide for a better photo-op but also provide for a benefit to a much larger area. It would be wrong to say that one set of priorities is “better” than the other, but it did appear to this author that, after many years of development priorities being set nationally, the pendulum had perhaps swung too far one way. The political party of the local Provincial Politician seems to be absolutely vital in determining whether a local area receives funding from the province. It may also have some limited impact in deciding whether a local area receives funding from the district.

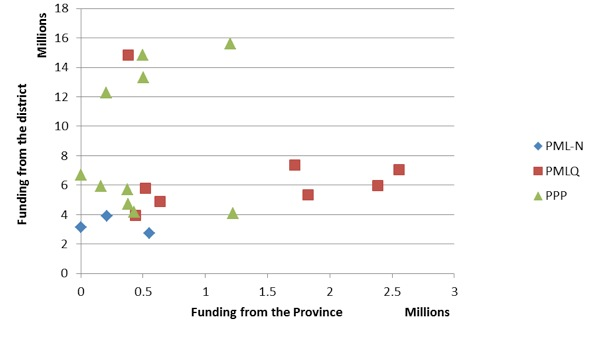

Figure 5. Average funding received by Union Councils within each MPA’s constituency from the province and from the district. (The chart – but not the calculations – omit the constituency PP55: a PML-Q constituency at the 10 million by 10 million intersection, ie a red square far to the right of the current graph. As such it is in keeping with the trend depicted here but cannot be shown without making the scale unwieldy)

This was analysed using the same dataset as in the previous experiment. Each Union Council was mapped into its corresponding provincial seat. An Anova test was then run for the statistical significance of the political party represented in that seat. This revealed a P-value of 0.060 for the political party of the provincial politician being statistically significant with regards to district funding but a P-value of 0.000010 when it comes to provincial funding.

Analysis: as we can see from the graph, being a member of the PML-Q – the party that controlled the Punjab for the duration of the dataset – was absolutely key to attracting funding from the province. It is much less clear that there was any impact on district funding, or what that impact was.

Thus you could perhaps argue that patronage based on political parties is less evident in local government than provincial government. It was thought in some circles to be an open secret that the “non-partisan” Nazims were nothing of the sort, and were all of the political persuasion dominant in the area. This data could perhaps argue against that, although we must be careful – there are other ways to read it (perhaps, due to the trappings of power, all the Nazims were allied to the PML-Q) and we have only demonstrated a correlation, not ascribed cause. What does seem evident is that if you live in an opposition held area you have very little chance of attracting development funding from the province, but devolved local government might suit you better. Re-election as a Union Council Nazim is strongly dependent upon your ability to attract development funding to your Union Council. Yet it is far less clear that re-election as an MPA is dependent upon your ability to attract development funding for your constituency.

Analysing the data for the Union Councils for which we have accurate information shows that, on average Nazims who successfully stood for re-election in 2005 attracted 10 million rupees more funding per Union Council in the course of their term than those which were not returned – a finding with a p value of 0.021. However this is based upon a sample of only the 9.2% of union councils for which we have accurate election data. Nevertheless, given the seemingly random nature of the sample this is however a large enough sample for us to have some confidence in this finding. Indeed, using a sample size calculator we calculate that given the sample size is 26 we can have a 99% confidence in this finding with a margin for error of 12%. Putting this another way we can say with a p value of 0.031 that across Faisalabad winning Nazims attracted somewhere between 12,150,000 and 7,850,000 more development funding from the district than losing Nazims.

Unfortunately we cannot do a like-for-like analysis with the provincial data. The most approximate term of provincial elections to this term in local elections the 2002-2008 term. Sadly in 2005 the data provided by the SPU changes format drastically and significantly reduces the detail of the information available.

However, if we convert our 2001-05 data into the 2005-08 format and run a Pearson’s correlation coefficient test we can see that there is a strong positive correlation between the two sets of data – with a correlation coefficient of 0.24 and a P-value of 0.000010. In other words the two sets of data are very similar: spending patterns did not change markedly.

Therefore, it may not be entirely without value to extrapolate our 2002-05 data and attempt to apply it to the 2008 provincial election. If we do this then we discover that those provincial politicians that were successfully returned only attracted, on average, 1.4 million more rupees in provincial funding (out of a total spend of nearly 340 million) spent in their constituency in the course of the test period – giving a p value of 0.88. In other words, there appears to be no correlation at all between spending and re-election for provincial politicians. Of course this is an extrapolation based upon very incomplete data, and based upon extrapolating spending patterns for three years over six. But if politicians were behaving very differently in the second half of their term to the first then this is significant in itself.

Analysis: It may be that 2008 was simply a freak election. 2008 was a “change” election, in which the party of the former military dictator was swept from power, and it may be that this larger theme swamped any potential correlation there may have been.

Of the 22 provincial seats in Faisalabad, 12 changed hands. Moreover, in an election which elsewhere saw the PML-Q virtually wiped out, the PML-N come to power in the Punjab, and the PPP win the national election – Faisalabad bucked the trend.

Table 1. Election results for MPAs seats in Faisalabad in 2008.

| Now PPP | Now PML-N | Now PML-Q | Now IND | |

| Was PPP | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Was PML –N | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Was PML –Q | 3 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

However it would seem more likely that our data had no significance and was merely a consequence of the national picture if Faisalabad had followed the national trend rather than bucking it. At any rate, as the result of the election was the return of traditional, anti-devolution, political parties, the Nazim system never lasted long enough for us to find out.

But, subject to these many caveats, it does appear that re-election is far more closely tied to “achievement” (as measured by the ability to attract development spending) in the local system than it is in the provincial system.

Of course we have shown correlation not causality and so we can only speculate as to what that means. Potentially it could mean that, if being a good politician is measured by attracting funding for your area, then it would seem that local elections are more meritocratic than provincial ones. But that is a substantial if; perhaps it shows the maturity in provincial elections in that they are less susceptible to such reductive voting patterns and other factors come into play.

A few further reflections

One thing everyone, even the provincially appointed administrators themselves agree upon is that the reintroduction of the primacy of the provincial layer has made government more distant. This is literally true: whereas previously there was a Union Councillor in virtually every village, and a Union Nazim within 2 or 3 miles of every village, now one must go to the municipal offices in central Faisalabad to contact the state (a distance of some 50 miles from some parts of Faisalabad district) or find a telephone or email, which for many rural Punjabis is an even greater challenge.

It is also metaphorically true: by the Faisalabad DCO’s (District Coordinating Officer – the civil servant who now runs a district) own admission, he does not have the time or the resources, and does not consider it his role, to make himself available for discussion with the public – far less to go out and talk to people on their doorsteps. For many, interface with the state is now a matter of knowing people in high places: in other words of the system of brokerage and patronage.

Perhaps the most valuable role Nazims could have played was in interfacing with the state – forming a link between local people and the bureaucracy which did not necessarily require brokers or “big men”. This is a hard thing to quantify but a UNDP social audit report (2010), and the testimonies of residents, suggest that this did happen in many cases.

Perhaps for this reason Local government is very popular with the Pakistani public, as is shown in satisfaction surveys. Opinion polls suggest 64% want directly elected system of Local Government whilst 79% oppose a return to the 1979 system (FAFEN, 2009).

Conclusion

The dominant view held within Pakistan is that, however flawed the current crop of political parties are as vessels for the aspirations of the people of Pakistan, democracy in Pakistan will only grow and deepen if it does so through the existing political parties. These political parties remain deeply wedded to government through the provinces.

Yet devolution increases the ability for the public to interact with the state, and the level to which good performance in attracting development is rewarded electorally. It counteracts the bureaucracy and national politicians’ distain for the kind of unexciting, small, hyper-local, development projects – such as the village sewer – which were so overlooked under the previous system. It made larger projects more difficult, but arguably there had been an over concentration of resources on larger development schemes – perhaps not schools and hospitals but certainly flyovers.

However, it does not support the idea that a process of democratic deepening is taking place, as defined, from Wilder (1999) as the motivation of voters horizontally rather than vertically – indeed insofar as the data presents an opinion it is that the opposite is taking place

Purely from a development perspective, it seems having spending determined by the lowest tier has several advantages over its being determined by the province. It is more equitable and reliable, and it seems to manage to reward good performance. One Union Nazim told me that before the 2001 devolution there had been no development in his area for 60 years: if you were overlooked in the previous system you remained overlooked. The fact that every small area had a champion of sorts was certainly a positive development. This argues strongly, again from a purely developmental perspective, in favour of attempting to devolve decisions regarding development to a sub-provincial democratic tier.

In developing countries there is a legitimate role of an elected official in championing ones area when it comes to development. On the other hand, surely it is not healthy to regard “meritocratic” elections purely in terms of the politicians’ ability to attract development projects. As Ali Cheema said to me, “why should we aspire to elect a politician based upon their skills when it comes to pork-barrel spending?”

Making democracy about Wilder’s (1999) horizontal, rather than vertical, divisions, and electing politicians based upon something other than patronage, involves moving away from the obsession with local public goods and towards parties, ideologies, and manifestos – the building blocks of modern politics. Currently this is only happening at the provincial tier.

However the positive attributes of devolution and of developing a system of elected local government could bring benefits too – for political parties are as poorly served as everyone else by the lack of engagement at the grass roots. The roots of Pakistani democracy are shallow and, whilst the reasons may be historical, part of the solution is surely for political parties to become more local and interact directly with the public, thus eventually superseding brokers and similar networks of patronage. Political parties in Pakistan may be right to feel that at the local level they will be outcompeted by local elites, but the mistake they make is to think that means they must utterly ignore the local level.

—

Fred Carver is a PhD candidate at Kings College London, investigating the effects of urbanisation on patronage and power in the Pakistani Punjab. He previously had a career in British Politics and has written and spoken on elections and democracy in Africa, Central Asia and South Asia for television, radio, newspapers, blogs and journals. He also has a “day job” running a small human rights NGO: the Sri Lanka Campaign for Peace and Justice.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the City District Government of Faisalabad for placing so much financial information in the public domain and so making this study possible. All my interviewees were very generous with both their time and their knowledge. Professor David Taylor’s encouragement, knowledge, approachability and contacts are what made this paper possible. Of those he introduced me to, in particular Professor Ali Cheema and Professor Mohammed Waseem of LUMS were invaluable in their insight and suggestions for the direction this paper should take. Azhar Ali of the DfID and Zaman Khan of the Human Rights commission for Pakistan went to great lengths to provide me with contacts during my time in Pakistan, all of who were helpful, professional and candid. In addition Zaman and his colleagues Iftikhar and Qasar Daniel were extraordinary generous and informative hosts and guides both in Faisalabad and Lahore. All numbers are given to two significant figures and all errors are my own.

References:

Full list of those interviewed (in chronological order):

- Asif M Shah – Public finance specialist, Local Government, Asian Development bank

- Ali Azhar – Governance advisor, DfID

- Dr M Yasim – Thesil Nazim, Saddar Town, 2001-2005

- Syed Sadar Bukhari – Vice President, District Bar Association

- Anonymous police officer

- Dr Hamir Raza – journalist and publisher of the Daily Gulf

- Malik Mohammed Aslan – President, Faisalabad Press Club

- Mr Siddiqui – resident editor, Daily Mussavat

- Sheikh Quaram – President of Faisalabad Centre of Commerce

- Zaman Khan – Human Rights Commission of Pakistan

- Chaudhry Talib Hosseini – former basic democrat, MPA, MNA, and minister

- Saema Syed – Assistant Financial Secretary: Social Services, Government of the Punjab

- Mohammed Mahmood Rai and his deputy – Assistant Financial Secretary: local government, Government of the Punjab

- Faisal Rashid – Assistant Secretary: Finances, Government of the Punjab

- Sheryar Sultan – Assistant Secretary: Local Government, Government of the Punjab

- Professor Ail Cheema – LUMS

- Mohammed Arshad – Assistant Financial Secretary, budget director, Government of the Punjab

- Iftikhar (surname unknown) – Sustainable development for Pakistan (NGO)

- Abdul Sattar and his son – Union Nazim UC 160

- Farzana Choudhry – Union Nazim UC 207

- Miah Taharayyub – Union Nazim UC 206

- Saeed Wahla – DCO Faisalabad

- Zia Ul Haq – Deputy Commissioner (local Government), City District Government of Faisalabad

- Dr Tariq Sattar – Director development finance for Faisalabad, Jhang, Chiniot and Toba Tek Singh, former director SPU

- Abdul Mohamadin – Assistant election commissioner, Election Commission of Pakistan

- Professor Mohammed Waseem – LUMS

- Mr Rehman – Chair, Human Rights Commission of Pakistan

Works consulted:

ADB, 2010, Project information document Available from http://www.adb.org/Projects/project.asp?id=34328 [Accessed 18/02/2011]

Ali, T., 2009, The Duel: Pakistan on the Flight Path of American Power, London: Simon & Schuster

Ali., S. M., and Saqib, M. A., eds, 2008, Devolution and Governance Reforms in Pakistan, Karachi: Oxford University Press

Anon, 2010, Unpublished manuscript, Lahore: unpublished

Bardhan, P., and Mookherjee, D., 2001. “Corruption and Decentralization of Infrastructure Delivery in Developing Countries”, Journal of Development Economics, Available from http://grade.org.pe/eventos/lacea/papers/ddinf1.pdf [Accessed 14/09/2010]

Cheema, A, Khwaja. A. I, and Qadir., 2005, Local Government Reforms In Pakistan: Context, Content And Causes. Available from http://www.hks.harvard.edu/fs/akhwaja/papers/Chapter8.pdf [Accessed 14/09/2010]

Cheema, A., and Mohmand, S. K., 2006, Bringing Electoral Politics to the Doorstep: Who Gains Who Loses? Available from http://www0.gsb.columbia.edu/ipd/pub/Cheema_revised.pdf [Accessed 14/09/2010]

Cheema, A., Khan, A., and Myerson, R., 2010, Breaking the countercyclical pattern of local democracy in Pakistan, Available from http://home.uchicago.edu/~rmyerson/research/pakdemoc.pdf [Accessed 14/09/2010]

Dewey, C., 1993, Anglo-Indian Attitudes: The Mind of the Indian Civil Service, London: Hambledon Press.

DSD (ADB, DfID and World Bank), 2003, Devolution in Pakistan – preparing for service delivery improvements, Islamabad: DSD

DSD (ADB, DfID and World Bank), 2006. Devolution in Pakistan: Volumes one, two and three, Islamabad: DSD

Estache, A., and Sinha, S., 1995, “Does decentralisation increase public infrastructure expenditure?” in Estache, A. eds, Decentralizing infrastructure: advantages and limitations Washington: World Bank

FAFEN, 2009, Reform, But No Rollback. Local Government System: A View from the Districts Online, Islamabad: FAFEN, Available from http://www.fafen.org/v1.fafen/admin/products/p4a82956dbc6c1.pdf [Accessed 14/09/2010]

Geddes, B., 1994, Politician’s dilemma: building state capacity in Latin America, Berkley: University of California Press

Gelner, D. and Hachhethu, K., eds, 2008, Local democracy in South Asia: microprocesses of democratization in Nepal and its neighbours, New Delhi: SAGE Publications

ICG, 2004, Devolution in Pakistan: Reform or regression?, Available from http://www.crisisgroup.org/library/documents/asia/south_asia/077_pakistan_devolution.pdf [Accessed 14/09/2010]

Jamil, M., 1996, Local government in LDCs and some related issues, Lahore: Ferozsons

Kennedy, C., 2001, Analysis of Pakistan’s devolution plan, Islamabad: DfID

Khan, S. R., Akhtar, A. S., and Khan, F. S., 2007, Initiating Devolution for service delivery in Pakistan: Ignoring the power structure, Karachi: OUP

Kitschelt, H., and Palmer, D., 2009, Expert Survey on Citizen-Politician Linkages: Initial Findings for Pakistan in Comparative Context, Durham (NC): Duke University Press

NRB, 2005, Community Empowerment under Devolution: Progress, Challenges and the Way Forward, Islamabad: NRB

Pattan, 2005, Role of Civil Society Organizations in Local Government Election 2005, Islamabad: Pattan

Rehman, I.A., 1999, No Room for Illusion, The News International, 14/11/1999

Shaikh, M., 2007, Satellite television and social change in Pakistan: a case study in rural Sindh, Karachi: Orient books

Smith, A., 1776, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, London:Methuen & Co., Ltd.

Stigler, G., 1957. “The Tenable Range of Functions of Local Government.” In Joint Economic Committee, Subcommittee on Fiscal Policy, U.S. Congress ed, Federal Expenditure Policy for Economic Growth and Stability, Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Takashi, K., 2006, “Community and Economic Development in Pakistan: The Case of Citizen Community Boards in Hafizabad and a Japanese Perspectives (sic)”, The Pakistan Development Review, 45

UNDP, 2010, Social audit of local governance and delivery of public services, Islamabad: UNDP

Wajidi, M., 2000, Local government in Pakistan: a case study of K.M.C., Karachi: Royal Book Company

Waseem, M., 1994, The 1993 Elections in Pakistan, Karachi: OUP

Waseem, M., 2000, Devolution plan: a critique, Dawn, 11/06/2000

Waseem, M., and Burki, S., 2002, Strengthening democracy in Pakistan, Islamabad: DfID

Waseem, M., eds, 2002, Electoral reform in Pakistan, Islamabad: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung

Waseem, M., 2006, Democratization in Pakistan : a study of the 2002 elections, Karachi: OUP

Wilder, A., 1999, The Pakistani voter : electoral politics and voting behaviour in the Punjab, Karachi: OUP

Yusufzai, R., 1999, As and when deemed fit, The News International

Zadai, S., 1999, The new development paradigm: papers on institutions, NGOs, gender and local government, Karachi: OUP

1. The decision to use a version of relative mean difference (RMD) as a measure of the equitability of distribution instead of standard deviation (SD) was based upon the fact that RMD, unlike SD, is not defined in terms of a specific measure of central tendency – and the central tendency for development spending in the Punjab has not been determined. The Gini Coefficient was chosen as Gini is a scaled version of RMD (RMD=Ginix2) and so occupies a more pleasing 0 to 1 scale and will be more familiar to political scientists as a measure of inequality. Whilst direct comparison with the Gini coefficients of the wealth of nations is to be avoided – they are not directly comparable – it will give readers an idea as to what constitutes a high or low coefficient.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Pakistan’s New Approach to Gilgit-Baltistan

- The Challenges and Inconsistencies of the Iran-Pakistan Relationship

- Opinion – Is the Coronavirus War Narrative Helping Pakistan?

- Pakistan’s Role in Western and Middle East Security

- Opinion – Pakistan’s Perilous Status

- Opinion – The Contours of the Saudi Arabia-Pakistan Relationship