President Nicolás Maduro celebrated his first year in power in Venezuela on April 19th 2014. Though he ascended to the post on an auspicious date, the anniversary of the protests against Spanish rule that marked the beginning of the independence movement in Venezuela, his first year in power has been marked by protests against him and not as the continuation of the Bolivar-inspired style of governance of his predecessor. Despite increased national revenue from soaring oil prices, protests have been larger and more frequently oppressed than any since the beginning of Hugo Chavez’s government and his political ideology (Chavismo) in 1999. Moreover, Maduro has received support (or at least a kind blind eye) from neighbors (Cave 2014) as he battles to contain the protests and carry on with the next five years of his term.

I argue that Venezuela’s considerable oil endowment has played a dual role in the current protests. On one hand, oil income has not been effective at reducing the protests domestically. On the other, oil has been effective at maintaining the support for the regime internationally. Specifically, protests have risen in spite of a steady increase in the price of oil. At the same time, neighboring countries and the regional multilateral organization have, at best, ignored the increasing levels of unrest in Venezuela and, at worst, discredited it (The Economist 2014; Correa Guatarasma 2014).

Though protests are not a new phenomenon in Venezuela, both the scale of the protests and the level of repression against them are new to Venezuela and to Chavismo. Existing work in political science has shown that protests were occurring in Venezuela even during the period in which the country was being touted as the best example of Latin American democracy. Margarita Lopez Maya, Edgardo Lander, and Dick Parker argue against Venezuelan democracy’s exceptionalism and find that the frequency and themes of the protests of the 1980s were comparable to those of the golden period in the 1970s, though the latter did not receive as much attention (Maya, Lander, & Parker 2005).

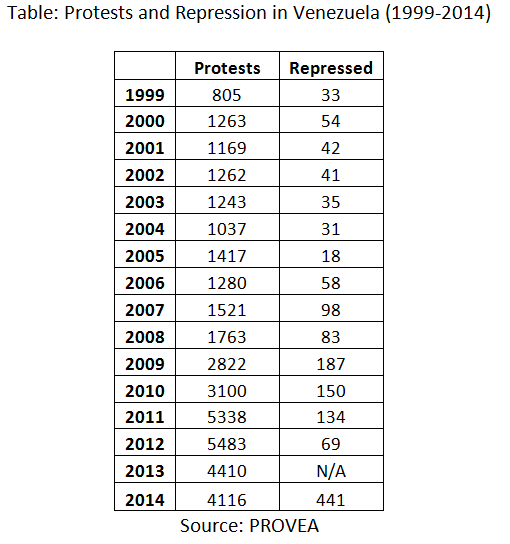

Recent protests, however, far exceed anything that has been seen in Venezuela, as shown in Table 1. According to the local NGO Observatorio Venezolano de la Conflictividad Social (Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict), there were 4,116 protests in the first three months of 2014. Another Venezuelan NGO, the Foro Penal Venezolano (Venezuelan Penal Forum), estimates that since February of this year, 2,118 people have been arrested for protesting, including opposition leader Leopoldo Lopez (De la Rosa 2014). Both the scale and frequency of the protests, and the degree of repression, indicate a move toward authoritarianism by Nicolas Maduro. If the trend continues, 2014 is on track to see 16,000 protests.

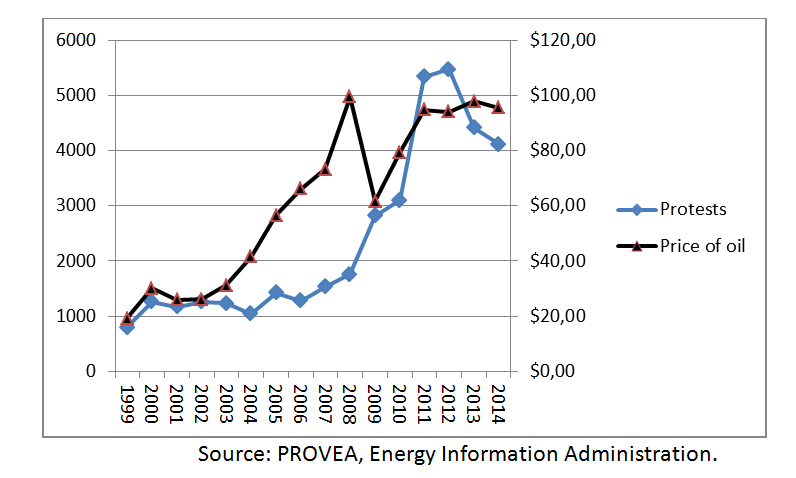

Moreover, the recent protests have come despite increased revenue from oil prices, which are about $35 per barrel above the price that Venezuela had anticipated when it created its budget for 2014. Taking into account just exports to the US (which decreased to 792,000 barrels per day from a high of 1.6 million barrels per day in 1998), Venezuela is receiving $27 million dollars per day more than it had expected it would. That the protests come at a time of high oil prices is surprising, considering that Venezuela’s last major urban protest, the Caracazo, marked the end of the oil bonanza years (Maya 2003). The Caracazo occurred when oil prices were tumbling, prices were being liberalized, and the cost of gas and public transportation was doubling overnight (Corrales 2003).

Graph: Protests in Venezuela and the Price of Oil

The recent protests are different in that they are coming in a time of oil bonanza, if not economic bonanza. According to the Observatorio, the protests are a response to high indices of criminality, food shortages, inflation, and the right to free speech. Some of the protests have also been self-referencing in that people have taken to the streets in response to the repression to protest that their right to political participation is being denied.

Not all of the causes of the protests could have been addressed through better use of oil revenue and increased production. It is unclear how high oil prices would affect homicide rates or free speech. Food shortages and inflation, on the other hand, are primarily a direct result of mismanagement of the long-running exchange rate control and nationalization of consumer industries.

In January of this year, 26 of every 100 essential food items were unavailable to consumers due to severe shortages (Salmeron 2014). Some of the items missing from grocery shelves are items that were produced in Venezuela by companies that have been nationalized. This was the case for Cargill’s rice plants in the country, which were nationalized in 2009 (El Universal 2010). The second direct cause of food shortages is price regulation of essential items, which has discouraged their production. Production of the varieties of cheese for which price is regulated, for example, has fallen steadily since 2010, as producers have shifted to producing other types of cheese (El Universal 2010).

According to the country’s Central Bank, Venezuela’s annual inflation rate rose to 57.3% in February, the month the protests started. Inflation is partly a response to the food shortages and to the country’s exchange rate control regime. Though the exchange rate regime has been frequently modified since it was first implemented more than a decade ago, it continues to distort the currency. The Economist’s Big Mac index, for example, estimates that the Bolivar Fuerte is overvalued by more than 50%, making it perhaps the second most overvalued currency behind the Norwegian krone.

Maduro could better administer the significant oil windfall to address at least the economic concerns of the protesters, if not those associated with the quality of democracy. The silence of Venezuela’s neighbors and the refusal of the Organization of American States (OAS)[1] to hear the oppositions’ side, however, allow Maduro room to dismiss the protesters as long as they are not undermining the international legitimacy of his regime.

Thirty-five states are members of the OAS, including Cuba, though as a non-democratic state, it has been excluded from participating since 1962. The member states vary tremendously: the economy of the United States, the largest member state, is more than 16,000 times larger than that of its smallest member, St Kitts and Nevis. Yet the Americas are the birthplace of the principle of sovereign equality, so the vote of St Kitts and Nevis has the same weight as that of the United States (Finnemore & Jurkovich 2014).

The principle of one-state, one-vote is central to multilateralism. However, it allows the more astute players in the system to use their power to ensure that their influence in the organization exceeds the one vote granted to it. In the case of Venezuela, the regime leveraged its access to oil to win the favor of some of the smaller players in the OAS. Venezuela’s outsize influence in the OAS has been put to the test as opposition and protest leaders have tried to get the organization to address the situation in the country.

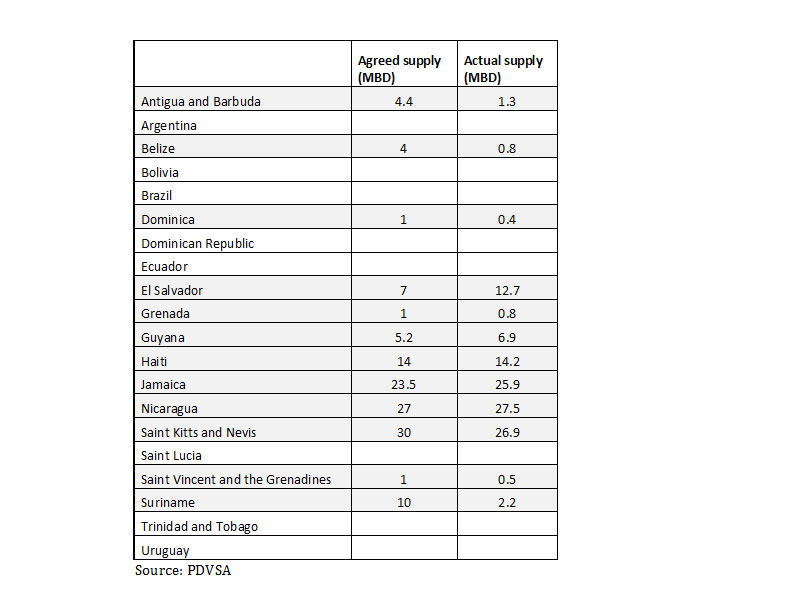

The treatment of opposition parliamentarian Maria Corina Machado demonstrates this outsize influence. In March, Panama volunteered to make Machado a temporary member of its diplomatic delegation to the organism and to cede to her their allotted speech time (El Universal 2014). Prior to Machado’s remarks, a vote was taken on whether to allow the media to attend for her presentation. Nicaragua put forth a motion to have a closed-door meeting for Machado’s presentation. Twenty-two countries voted in favor of Nicaragua’s motion, eleven voted against, and one country, Barbados, abstained. The eleven countries that voted against Nicaragua were Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, México, Paraguay, Peru, and the United States (El Universal 2014). Of these, only Honduras participates in Venezuela’s subsidized oil program, Petrocaribe, though it has not yet received any oil from the country. Guatemala withdrew last year (Fieser 2013). In contrast, nearly all of the countries that voted in favor of keeping the media out of the event are beneficiaries of Petrocaribe, with Nicaragua being the biggest recipient of Venezuelan crude (Grisanti 2011).

Table: Countries that voted against allowing the media in (voted with Nicaragua) and their participation in Petrocaribe (in millions of barrels per day, 2012)

The vote at the OAS illustrates how an oil-rich regime might be able to influence a multilateral organization. However, it is not clear how far the example would be able to travel outside of this context, since the conditions present at the OAS are in some respects unique. In this organization, the largest member and the most oil-rich member are not the same. Moreover, the interests of the largest member and those of the oil-rich member are very different. Second, the membership is relatively small; a group of only 18 states constitutes a majority. Third, the largest member has appeared uninterested in the organization (and arguably in the region as a whole) and has not tried to court the votes of the smaller states (or at least it has not done so as actively as Venezuela has).

Of the 22 countries that opposed media access to the meeting, 18 were beneficiaries of Petrocaribe. Venezuela exported close to 100,000 barrels daily to the 14 Caribbean countries members of Petrocaribe. At the OAS, these countries joined larger countries that have been supporters of the regime – Bolivia, Ecuador, Brazil – in keeping the media out of the meeting. Though Maduro has apparently been unable to use oil to stem the protests, he is benefitting from his predecessor’s use of oil to gain influence in the region. Thus, the protests are not being calmed by oil largesse, but rather, increasingly repression in Venezuela is being ignored by the influence of oil. While oil does not seem to be contributing domestically to Maduro’s staying in power, it is providing important leverage internationally that allows him to carry on, especially since there won’t be a presidential election until 2018.

[1] OAS is the regional organization charged with promoting and consolidating representative democracy.

References

Cave, D. 2014, ‘Response from Latin American leaders on Venezuelan unrest is muted’, The New York Times, 22 February 22.

Corrales, J. 2003, Presidents without parties: The politics of economic reform in Argentina and Venezuela in the 1990s, Penn State Press.

Correa Guatarasma, A. 2014, ‘Jacobson: US disappointed at OAS’ stance on Venezuela’, El Universal, 30 April 30.

De la Rosa, A. 2014,‘Foro Penal reporta 2.118 detenciones en todo el país’, El Universal, 3 April.

El Universal 2010, ‘Cronología de nacionalizaciones y expropiaciones en Venezuela desde 2007’, 26 October.

El Universal 2011, ‘Producción de quesos disminuyó 8,35% durante 2010’, 27 April.

El Universal 2014, Conozca los países que votaron a favor y en contra de la sesión pública, 21 March.

El Universal 2014, Panamá cederá asiento a María Corina Machado para que hable en la OEA, 18 March 18.

Fieser, E. 2013, ‘Venezuela’s regional energy program Petrocaribe wobbles’ The Christian Science Monitor, 15 November.

Finnemore, M. & Jurkovich, M. 2014, ‘Getting a Seat at the Table: The Origins of Universal Participation and Modern Multilateral Conferences’, Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, vol. 20, no 3.

Grisanti, A. 2011, ‘Venezuela’s Oil Tale’, Americas Quarterly, Spring.

Maya, M. L. 2003, ‘The Venezuelan Caracazo of 1989: popular protest and institutional weakness’, Journal of Latin American Studies, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 117-137.

Maya, M. L., Lander, L., & Parker, D. 2005, ‘Popular protest in Venezuela: Novelties and continuities’, Latin American Perspectives, pp. 92-108.

Salmeron, V. 2014, Escasez de alimentos en enero es la más alta en cinco años, El Universal, 13 February.

The Economist, ‘Protests in Venezuela: Stop the spiral’ 2014, March 1, 2014.

World Bank. ‘Indicators’, accessed 1 April, 2014.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Disputing Venezuela’s Disputes

- Venezuela: A Difficult Puzzle to Solve

- Opinion – The Survival of Venezuela’s Bolivarian Revolution

- China-Venezuela Relations in the Context of Covid-19

- The Venezuelan Crisis: Maduro’s Regime Legitimacy and Potential Outcomes

- Opinion – Venezuela’s Migrants and the Challenges of Trinidad and Tobago