Introduction

This project will aim to explore and discuss whether there has been a change in national party system mechanics in Croatia, as a result of Europeanization and EU influence. It will explore the Europeanization approach and draw conclusions as to whether specific changes in the Croatian national party system can be attributed to pressure from the EU. Through looking at the changes in two different time-frames, from 1999-2004 and 2005-2013, it will be possible to discuss the variations that may take place, and as a prediction, the further Croatia is said to be Europeanized, the more pro-European change we should see in the national party system. The pioneers of the framework of research into the Europeanization of political parties and party systems (Mair 2000 and Ladrech 2002) have traditionally defined three areas of National Party Europeanization: national political parties: the national party system and the transnational party level of organization and functioning. This project will focus only upon the national party system, including its mechanical framework, as this will assist in the understanding of the political significance of parties.

Background

The widespread currency of the term Europeanization has been hotly debated by political scholars for more than a decade, with strong belief that there is no single and correct definition of the approach. Europeanization, like globalization, can be considered a useful entry point for greater understanding of important changes occurring in politics and society. It is not simply a synonym for European regional integration or convergence (Featherstone, 2003). Research regarding Europeanization has developed primarily in the context of the EU’s eastern enlargement, linked with the transition to democracy, the market economy, and the adaptation to the exigencies of the Western models. Gradually, as the scope of Europeanization has widened, it is now applied to an extensive range of referent objects, including the Western Balkans. Europeanization is most often associated with adaption to the pressures emanating directly or indirectly from EU membership. However, it is also important in the exploration of the rapid changes that have been undertaken by European candidate countries in the escalation to EU membership.

Europeanization is present in day-to-day national policy and its influence on domestic politics can be seen in varying degrees in most EU member and candidate states. Although Europeanization through European integration is based on the same EU principles, rules and procedures, its impact varies in practice from country to country (Anastasakis, 2005). For the Western Balkans, Europeanization has meant adjustment to advanced western models alongside security and prosperity for the future. New member states of the EU like Croatia are regarded as more similar to candidates than longer-standing members, as the adjustment pressures of membership are different for those states who did not participate in the making of the rules (Sedelmeier, 2011; Bulmer and Lequesne, 2012). Moreover, the distinctive nature of candidate country Europeanization raises questions as to how durable the EU’s pre-accession influence is, and how much change regarding EU-aspiring countries it is responsible for.

There is no doubt that Europeanization as a result of European accession has had a profound impact upon the public policy functions of the aspiring member states. Regarding the Western Balkans this emulates from the ‘Stability and Accession Processes’ negotiated by the EU where countries including Croatia were made to fulfil a high degree of alignment to the EU acquis. This has resulted in considerable changes to the national party system mechanics which as a result affects the governing body, the voters and the domestic institutions.

Context

Croatia became the 28th member state of the EU on 1 July 2013, having first applied in 2003. Their application for membership was then confirmed in June 2004 and accession talks began in 2005. The closure of accession negotiations, arguably the most difficult in the history of the EU enlargement, was a historical success for a country of the Balkans.

As a member of the former Yugoslav republic, it is recognition that Croatia has conquered its chequered past, even though the country was shattered by war less than 20 years ago. The long-lasting continuity, sustainability and irreversibility of the reforms in Croatia through EU accession can be seen as a token for the future effective functioning of Croatia as an EU Member State.

In a May 1991 referendum, following the collapse of Communism in Europe, over 93% of Croatian citizens voted for a ‘sovereign and independent Croatian state’ free from the Serb-dominated Federal Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia (Vukovar, 2008). The Croatian War of Independence was then fought between 1991-1995, with the objective that Croatia would leave Yugoslavia and become a sovereign country with independence and preservation of its borders. The war ended with a total Croatian victory, but however, much of Croatia was devastated, with estimates ranging from 21-25% of its economy destroyed and an estimated US$37 billion in damaged infrastructure, lost output and refugee-related costs (Europe Review, 2003: 75). The main challenges Croatia faced as a newly established republic were the consolidation of the statehood, the building of new institutions and the upheaval of the economy.

Many post-socialist countries have been confronted with the challenges associated with transformation; socio, economic and politico-institutional (Fink-Hafner, 2007). The Croatian case displays almost all of the typical controversies and challenges associated with the former Yugoslav successor states that subsequently developed a dependency on EU funding and support. As a result of the costs accrued from war, Croatia found itself victim to financial dependence on the West due to its feeble economic situation. The international recognition of the Republic of Croatia on 15 January 1993 marked the beginning of the development of relations between Croatia and the EU. Since it joined in 1993, Croatia has also received a great deal of support from the World Bank ($2.254 billion in 2013) with the global development institution assisting through financial and technical assistance, policy advice and analytical services (World Bank, 2014).

The SAP is the EU’s policy framework for the countries of the Western Balkans – Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Serbia and Montenegro. It was launched in June 1999 and strengthened at the Thessaloniki Summit in June 2003 incorporating elements of the accession process. The countries of the Western Balkans were involved in a progressive partnership with a view of stabilising the region and establishing a free-trade area through common political and economic goals. Interestingly, Croatia is the only state to have succeeded in gaining membership to the EU at this point in time, and therefore could be seen as a role-model for other candidate states.

Croatia has been chosen as a case study in this project due to being the only member state of the Western Balkans that has achieved membership from completion of the SAA/SAP as set by the EU. Extensive research has already been undertaken by scholars regarding the Europeanization of both the domestic and foreign policies of the countries of the Central Eastern enlargement era and some of this research will lay the foundations for the analysis of national party systems throughout this project (Ladrech 2005; Sedelmeier 2011). However, there is a distinguishable gap of scholarly work regarding the Europeanization of the countries of the Western Balkans.

The Croatian political system is a parliamentary, representative democracy where the Prime Minister is the head of government in a multi-party system. This multi-party system contains numerous parties in which it is highly unlikely that one party will ever have a chance of gaining power alone, imposing collaboration between parties to form coalition governments. A statistic from the 2011 parliamentary election suggests that there are 116 registered political parties in Croatia (Europa, 2014). However, the two main parties, the SDP and the HDZ, are both very different in terms of policy aims and ideology. The SDP are a centre left party, firmly grounded in ideas of social democracy and anti-fascism. The HDZ are centre-right, and firm believers in Christian democracy and national conservatism. These two parties rely heavily oncoalition building with smaller parties and therefore party system mechanics are often changeable as a result of elections.

Methodology

This project aims to employ an intrinsic case study method to identify how Europeanization has affected national party systems in Croatia. It looks to support the argument that Europeanization has had a significant effect on changes to the national party system by focusing on a single country as a case study. Through examining using case study methodology it ensures intensive scrutiny throughout the project. I aim to make the findings of this project internally valid, contributing the previous academic literature on national party systems in Croatia.

Case studies emphasise detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions and their relationships (Burnham, 2008; Halperin and Heath, 2012).

This project aims to employ this methodology as a powerful tool for examining whether the concept of Europeanization can be successfully applied to an area as specific as Croatian national party systems. However, the main limitation of a case study that is this specific is that it may be ungeneralisable to other contexts. This hurdle may be overcome by Chapter 1 – a chapter that will discuss the approach of Europeanization, as this research could be applied to alternative domestic policy areas in different European countries.

Content Analysis involves the systematic analysis of textual information. Due to both time and financial constraints, it became impossible to complete any primary research for this project. It could be argued that if primary research had been conducted through qualitative interviews, particularly in the area of voter attitudes towards Europeanization, it could have increased the overall validity of the project. As a result of this predicament, the alternative has been to use secondary research, which may have been subject to bias from those who have conducted or cited it. Content analysis enables access to subjects that are impossible to research through direct personal contact, and also allows the study of more documents and journals than would be possible through either interviews or direct observation.

The empirical focus of the project is limited through the general focus of the Europeanization literature on the domestic response to top-down adjustment pressures stemming from the EU hierarchy. The dependent variable of the analysis will be the extent to which the EU has influenced national party change in Croatia. To concur, the general purpose of this project is to understand the political significance and political change visible in national party systems when states are heavily impacted by the EU.

List of Abbreviations

EU – European Union

SAP – Stabilisation and Accession Process

CEEC’S – Central Eastern and European Countries

EFTA – European Free Trade Association

SAA – Stabilisation and Association Agreement

HDZ – Hrvatska Demokratska Zajednica – Croatian Democratic Union

SDP – Socijal demokratska Partija Hrvatska – Social Democratic Party of Croatia

HSLS – Hrvatska Socijalno-Liberalna Stranka – Croatian Social-Liberal Party

HSS – Hrvatska Selja čka Stranka – Croatian Peasant Party

HNS – Hrvatska Narodna Stranka – Croatian People’s Party

IDS – Istarski Demokratski Sabor – Istrian Democratic Assembly

HLS – Liberalna Stranka – Liberal Party

HKDU – Hrvatska kršćanska demokratska unija

SDSS – Samostalna Demokratska Srpska Stranka – Independent Democratic Serbian Party

EPP – European People’s Party

NATO – North Atlantic Treaty Organisation

WTO – World Trade Organisation

HSP – Croatian Party of Rights

ICTY – International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

EEAS – European External Action Service

CHAPTER 1: EUROPEANIZATION

The exploration of the impact of integration upon member states, applicants or neighbours of the European Union is elusively termed ‘Europeanization’. Robert Ladrech provided one of the first and most widely cited definitions of Europeanization; seeing the approach as ‘an incremental process reorienting the direction and shape of politics to the degree that EC political and economic dynamics become part of the organisational logic of national politics and policy making’ (1994: 69). Inherent in this conception is the notion that actors redefine their interests and behaviour to meet the imperatives, norms and logic of EU membership. Scholars who support Ladrech’s definition see Europeanization in broad terms; as a process of cultural, political and social change along European lines, within and beyond the borders of Europe. However, there are other scholars with a narrower view who choose to associate the term only with current member states of the EU (Mair, 2000). Conversely, when the approach is applied, it is clear that these different meanings are a result of the fact that Europeanization is internalized differently by various states or national actors, and that its degree of success relies on their ability and willingness to change (Anastasakis, 2005).

Europeanization speaks of a relationship between a member state and the EU, where any action taken must be coordinated at and between at least two levels, the domestic and the European, so that proposals in Brussels are consistent with national imperatives. There is consensus that, when trying to understand the impact of the EU on domestic politics, it is a two-way process: ‘member states are not simply passive recipients of pressures from the EU; they also try to project national policy preferences upwards’ (George, 2001: 1). As research has progressed, students of European integration have become increasingly interested in the impact of European processes and institutions on the member states, predicting convergence and cooperation in the national political system. This ‘top-down’ analysis concentrates on the effect of the evolving European system of governance on the member states. In conjunction with this ‘top-down’ coordination, it is argued there is an uploading process from the EU member states to the EU itself (Borzel, 1999). In this process, member states impact upon institutional changes at the EU level; a clear example being the creation of the EEAS.

The research interest in this project is restricted to the ‘top-down’ Europeanization of certain aspects of party system adaptation, as it assesses Croatia as a candidate state, and therefore uploading to the EU is arguably limited.

Radaelli’s definition of Europeanization includes processes of diffusion, construction, institutionalization of formal and informal rules, procedures, styles, appropriate behaviours and shared beliefs and norms (2000: 7). This definition is narrow and EU-centric through specification that rules and procedures are defined by the EU and only afterwards incorporated into domestic discourses, identities and political structures. Nevertheless, Radaelli importantly stresses the importance of ‘cultural encounters’ such as shared beliefs and norms (2000: 8). ‘EU-ization’ was a concept introduced by Helen Wallace, which differs from Europeanization regarding its particular focus on the EU, and its predominant concern with the transfer of institutional and organizational practices and policies (2000: 14). ‘EU-ization’ is guilty of disregarding cultural encounters, but despite this there is a great deal of overlap in content, agents, processes and structures. Europeanization concentrates on constitutive rules – that is, rules which constitute a community, whilst EU-ization is mainly concerned with regulative rules – that is rules which regulate behaviour within a society (Searle, 1995). This project will concentrate on the approach of Europeanization as opposed to ‘EU-ization’ as the empirical focus of Europeanization is far broader than the empirical focus of ‘EU-ization’. Furthermore, this project assesses changing voter attitudes with regard to the Croatian National Party System, which is a clear reflection of the cultural encounters that Radaelli references.

In addition, there is emerging literature and an exponential growth of research projects focusing on the impact of Europeanization and European Integration on domestic, political and social processes of member states. The majority of studies concentrating on Europeanization as a factor of domestic change find that there must be some ‘misfit’ (Borzel, 1999) between EU and domestic policies, processes and institutions. Borzel argues that Europeanization must be ‘inconvenient’, and that there should be an incompatibility between European level process, policies and institutions on the one hand, and domestic level processes, policies and institutions on the other (2003: Online).

To reiterate, in order to produce domestic effects, EU policy must be somewhat difficult to absorb at the domestic level. This degree of either ‘fit or misfit’ will then lead to adaptational pressures, which constitute a necessary but not sufficient condition for expecting domestic change.

In broad terms, the above is a result of the variations in the pressure emanating from the EU-level and therefore variations in the response of domestic actors and institutions according to how these pressures fit with domestic preferences and practices. This is very much the political aspect of Europeanization. It is also important not to forget that ‘fit or misfit’; through adaptational pressures and domestic responses to Europeanization are not simply static phenomena. Europeanization pressures are constantly in motion and ostensibly so are the domestic adaptations to them. Furthermore, it is important to consider that the term Europeanization acquires a different meaning through the different countries or regions involved in the process. Previous studies of Europeanization have dealt almost exclusively with countries that are members of the EU, yet similar, if not the same pressures, are exerted on applicants.

The Europeanization of candidate countries and new member states is a recent research area that has grown strongly in the past decade, primarily in the context of the Eastern Enlargement. The post-communist CEEC’s were arguably the first group of countries subject to direct attempts by the EU to influence domestic developments. The adjustment requirements of these candidate countries for membership did not solely focus on the adoption of the Copenhagen criteria and ‘acquis communautaire’ like applicant states previously. In addition to the acquis, the EU used the attractiveness of its membership incentive to influence the breadth of political conditionality and change proposed. The adaptational pressures for the CEEC’s were far higher than the 1995 EFTA countries, as the legacy of post-communism created high adjustment costs and therefore, the EU dictated an explicit pre-accession conditionality agreement. The creation of formal accession conditions gave the EU much wider leverage to pressure compliance from the member states. It also reduced the ability of applicants to negotiate concessions such as transitional periods and derogations in comparison with previous enlargements (Radaelli, 2003). Furthermore, this led to an increase in the study of the Europeanization of applicant states. This is because these countries were already subjected to substantially the same pressures of adaption to EU policies as current member states.

The successful conditionality agreement with the CEEC’s eventually led to the formation of the SAP proposed to the Western Balkans, in conjunction with the aim of eventual EU membership. Although the two conditionality agreements followed similar requirements, it is argued that the Western Balkan stipulation particularly concentrated upon adjustment to advanced western models through democratization. Additionally, through the SAP, the EU was making an effort to transfer rules and norms of democratic behaviour to new member states, going well beyond the domain of the single market (Bulmer, 2004). This progressive partnership aspired to stabilise the region, set out common economic and political goals and establish a free-trade area. The SAP’s were tailored to each individual country, with Croatia and Macedonia benefiting from a further accession partnership (the SAA), which took into account their specialist status as candidate countries. Progress with regard to EU integration was dependent on Croatia’s fulfilment of its commitments under the SAA.

This project will propose that Europeanization can be assessed through a process of institutionalization in which the stability of the party system evolves. Institutions refer to social phenomena that can create stable patterns of collective and individual behaviour. Olsen argues that institutional adaption ‘refers to the long term substitution of existing practices and structures with new ones’ (1997: 159). However, this point is in need of clarification. In practice it is clearly inefficient to demand replacement of the previous rules, norms and practices of the member states, which could lead to a loss of member state identity. Therefore institutional adaption should refer to the gradual transformation of these rules, practices and structures. In this project, institutionalisation of the national party system stems from previously stated institutional adaption through the EU’s indirect influence on national political systems and their practices. It is assumed that when a member state party system is institutionalised, voters are then able to make reasonable choices and as a result are able to put pressure on party orientations (Fink-Hafner, 2007; Sartori, 1976). Assessing the institutionalisation of a party system is best understood as a continuum of party system characteristics; stability of the main parties, party links with important state structures, political legitimacy, and strong party roots in society.

This project will also discuss the impact of Europeanization as a process of socialization. When an individual or state is a recipient to pressures from a higher influential level, sociological approaches argue that actors are guided by collectively shared understandings of what constitutes proper (e.g. socially accepted) behaviour in a given rule structure (Borzel, 2004). As a result, this can strongly influence the way that actors define their goals. According to this logic, member states and their elites then change their behaviour at the domestic level as a result of socialisation from EU pressures. This can be measured from examination of the links between national parties and European-level party federations, the support for EU integration from socialized elites and changing party characteristics under the influence of EU-level party federations (Fink-Hafner, 2007). The aforementioned ‘misfit’ of European policies can be assisted by socialization, which then may lead to the internalization of new norms by actors, such as national party elites.

One of the least researched areas regarding Europeanization is the EU’s impact on political parties, party systems and interest groups. Candidate country party system Europeanization has stemmed from research into effects of the EU on domestic politics. It is argued by some European Integration scholars, that Europeanization only acts in an indirect manner on national political parties (Ladrech, 2012). This reference relates primarily to the absence of direct and legal EU inputs into parties’ primary operating environments; such as rules, environments and campaigns. Therefore, it would appear that political parties and party systems are not, at first, ideal candidates to assess through an Europeanization research agenda, due to their insularity from EU influence. However, with the intention to explore the EU’s direct impact, we can argue that it is upon the domestic political environment in which parties operate, rather than on parties per se. Furthermore, party systems respond to indirect pressures that result from changes in the domestic political system, including public opinion and voter attitudes. Croatian voter attitudes will be assessed through this project, as a further assessment of Europeanization.

In terms of specific political parties, Enyedi and Lewis conclude that EU institutions and the European integration process in general, have been able to strengthen the position of some parties and weaken others. More importantly, through influencing coalition-making strategies and facilitating the ideological reorientation of certain parties, EU integration has contributed to changes in the mechanisms of party systems (Enyedi and Lewis, 2006). Moreover, this point clarifies that the EU has indirectly influenced the party systems in candidate states. However, the measurement of the aforementioned Europeanization effects is very important. There is a very clear risk that Europeanization studies may attribute all empirical findings of adjustment through indirect EU effects, when this may not be the case. Slovakia is the only example of an EU accession country where the EU has directly interfered in domestic politics, using the EU membership initiative as a sufficient instrument to intervene in party system dynamics. As a result, pro-European political parties emerged as election winners at elections and enabled Slovakia to remain in the 2004 EU enlargement group of countries.

Furthermore, regarding the Europeanization of the Croatian national party system, the changes are far more speculative regarding the party mechanism differentiation, and therefore it is difficult to distinguish between pressures from the EU and other domestic variables. In reference to accession, it can be claimed that party competition in Croatia may have been impaired by the decision of most parties in the political spectrum to remain unanimous over the policy content of the EU acquis, to remove any restriction from joining the EU as soon as possible. Nonetheless, this does not explicitly mean that all parties did agree, as there has been a visible rise in support for Eurosceptic parties since gaining official membership in 2013. The attention to the formation of Eurosceptic parties can be associated with generally higher levels of Eurosceptic public opinion, resulting from a more significant presence or intrusion of the EU in domestic affairs.

It is clear that Croatian national parties, as organisations, are removed from direct and legal obligations and effects by the EU. Although the EU may influence certain aspects of parties’ operating environments in the domestic political system, they are themselves insulated from direct EU inputs. However, research has proposed that with accession to the EU, new members become more engaged in internal processes, resulting in an excellent placement to influence the content, agenda and the direction of Europeanization. Therefore Europeanization is administered by the EU through an indirect process; using methods of institutionalisation and socialisation that stem from the accession criteria to instate this. It is important not to overlook other domestic external factors which may act as variables in the assessment of National Party Europeanization, and to recognise the effects that these may have had on any conclusions reached throughout this project.

Furthermore, it is also imperative that throughout this project, Europeanization is assessed as an externally driven process, whereby the EU acts as the main generator of changes and reform, and candidate and member states are legally bound to follow the set conditionality agreements.

CHAPTER 2: NATIONAL PARTY SYSTEM EUROPEANIZATION IN CROATIA FROM 1999-2004

The previous chapter examined the concept of Europeanization; through looking closely at both top-down and bottom-up approaches, the growth of study in the Europeanization of candidate countries, and concluded with a definition that can be applied throughout the investigation in this project. However, before exploration of the National Party System Europeanization of Croatia can be undertaken, it is necessary to define the term ‘party system’ in order to achieve a coherent analysis. Hague and Harrop provide the most accurate definition: ‘A party system denotes the number of significant parties and the patterns of interaction between them. In a democracy, parties respond to each other’s initiative in a competitive interplay’ (2007: 244). There are three overlapping formats of party systems; dominant – whereby one party outdistances all others, two-party – visible in the United States where two major parties compete for electoral support and thirdly multi-party systems – seen in Croatia. In multi-party systems, several parties achieve significant representation in parliament, becoming serious contenders for a place in a governing coalition. The underlying philosophy is that political parties represent specific social groups in historically divided societies (Hague and Harrop, 2007). Although this multi-party system is clearly visible in Croatia, where there are around 116 different parties that stand for election, it is also common to find in other European states, particularly the former Yugoslav Republics that have been through both the trauma of civil war (Lukic, 2008).

The exploration of national party system mechanics in the field of EU matters can be assessed through the following variables, as identified by Fink-Hafner 2007. Firstly, we must analyse the institutionalisation of the national party system, furthered by the European socialization of national party elites, and also changing voters’ attitudes towards their countries integration in the EU. This structure will be applied throughout this project, to identify a change in national party systems that can be attributed as a causality of Europeanization and EU influence.

This chapter will focus on the time period between 1999 – 2004, previous to Croatian EU membership conformation, but after Croatia had signed the SAA, the first formal contractual relationship with the EU. The Christian Democratic centre right (HDZ) regime in Croatia collapsed at the end of the 1990’s when controversial authoritarian leader Tudjman died in 1999. Driven by fear of a complete loss at the next election, in 2000 the HDZ abandoned the electoral system (that was driven by a majority structure) and replaced it with proportional representation. This electoral system change could be attributed as a contributing factor to any party system changes rather than Europeanization, and therefore this factor must not be dismissed. The key opposition party, the SPD, was created in 1999 after a merger of the relatively large Croatian League of Communists, Democratic Party for Change and Social Democratic Party of Croatia (Leakovic, 2004). The SPD won the 2000 election mainly as a result of the proportional representation regime, gaining power and beginning the transformation of key political institutions.

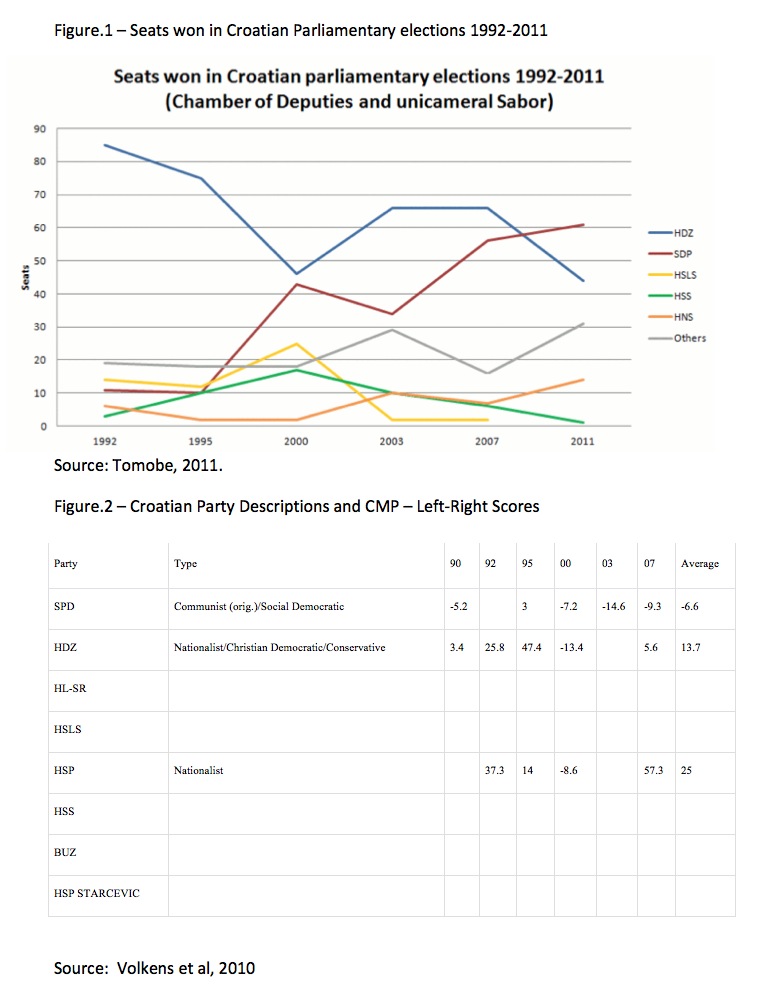

The full implementation of the SAA was intended to help Croatia in its preparations for EU Membership and set out common political and economic goals of which progress evaluation was based on Croatia’s own success and individual merits. Progress in the accession negotiations was dependent of Croatia’s fulfilment of the commitments set and failure would result in a likelihood of a far longer accession period. The demands set were extremely high, and arguably may have placed great strain on those parties that were in government at the time. In 2000 the Croatian SDP and the Croatian HLS parties held a majority in government by forming a coalition and winning the election with 38.7% of the vote, leading to the gaining of 71 out of 151 seats (Leakovic, 2004) [See Figure 1]. This was the coalition whom committed Croatia to the SAA, but the period it was in power was said to be marred with constant disagreement among coalition members on various economic issues, most of which were impacted by EU accession.

Institutionalisation of the National Party System

The institutionalisation of the national party system can be explored through many variations of analysis. This sub-section will concentrate on analysing the stability of the core parties in the national party system and the strength of party roots that are visible in society between 1999-2004.

If it were possible, this section would also explore the tolerance between a conflict of interests between members of party elites and other influential social positions, party links with important state structures (the military and the secret police) and influential veteran interest organisations (Fink-Hafner, 2007). However, due to restrictions and contradictory data, these influences have been discarded for use in this project. It can be argued that as the state becomes more Europeanized and more susceptible to European influence, the stronger the institutionalisation of the party system will be. This is because Europeanization will influence the inherent adoption of EU norms in the national party system.

It can be disputed that the HDZ’s defeat in 2000 was due to numerous circumstances; increasing dissatisfaction among the population (bad economic situation, corruption scandals) but mainly due to a voter demand for the Croatian government to seek assistance to become a member of the EU (Stojarova, 2013). As a multi-party system emerged, it is argued that Croatian social democrats looked to the example of social democratic parties of the more privileged stable democracies, in particular those democracies that were member states of the EU. The effort to achieve integration with western European structures represented an important influence in the consolidation of democracy in Croatia and the need for a more Europhile government. However, the HDZ were still strong in the political arena, and kept a large political following. In spite of the fact that more democratically orientated voters left the HDZ, it was only this party that did not lose its principal democratic support among the electorate.

In this time-period, it could be said that the Croatian party system did become institutionalized in some aspects, as there were several core political parties that retained powerful support in the system. Furthermore, it can be argued that there was a stabilisation of the parties in the Croatian party system as the electorate voted for a strong centre-left government who were very pro European integration. In their manifesto, the SPD coalition – combining the SDP, HNS, IDS and HSU parties, emphasised a ‘European path’ throughout the election, with ‘interests within the global European world’ (Kukuriku, 2011). However, research has concluded that both the centre-left parties (SPD coalition) and centre-right (HDZ) were both keen to pursue European integration and therefore the neutral policy of European accession may have impacted on the stabilisation of the core parties in the party system at this time (Leakovic, 2004; Storajova, 2013) [See Figure 3].

Secondly, throughout this period, there is a recorded drop in party identification by the public, showing an intensive retreat from party ties. Party identification was recorded as being around 56% in 1995, but by 2003 it had dropped to 36% (Cular, 2005). In conjunction with this, according to public opinion polls in 1990 and 1999 only about 12% of voter’s substantially or fully trusted political parties, whilst at the end of 1999 46% of the Croatian citizens interviewed did not trust the parties at all (Fink-Hafner, 2007). Overall, the picture of the Croatian party system between 1999-2004 shows that party preferences, party identification and the level of democratic legitimacy in the last election 2003, are lower than in the previous period. However, it is important to remember that in 2000, there was a change in the electoral system to proportional representation, which as Duverger suggests, encourages a multi-party system (Duverger, 1972). This variable of domestic political change may have affected the stability of the core political parties in the system and party identification – the institutionalisation of the national party system, rather than Europeanization.

The European Socialization of National Party Elites

The socialization of national party elites is a visible example of Europeanization as it suggests that interaction with other states or individuals will lead to shared conceptions of an identity or role, which further influences the creation of preferences of further cooperation and integration (Fink-Hafner, 2007). This construction can be assessed through; the links between national parties and European level party federations, the importance of EU level party links in relation to other party links such an international party associations and additionally changing domestic party characteristics under the influence of EU-level party federations (Vujovic, 2007). In terms of national party elites, socialisation can be seen through individual representatives of the party interacting with their counterpart European party federations. Since political parties in the potential candidate countries for EU integration have been traditionally centred on the extreme politicization of ethnic feelings, it is expected that the European socialization of national parties may be a relatively important factor in the assessment of party-system Europeanization. In candidate countries where all major parties are pro-western and reform-minded, international socialization has been smooth and has produced stable, consolidated democracies.

In contrast, in states dominated by nationalist, populist, and/or authoritarian political forces, international socialization has appeared to fail. An example of this would be Belarus under Alexander Lukashenko, which is often known as Europe’s ‘last dictatorship’ (Kelly, 2012).

Croatia is a state that has far longer experiences of links to European party federations and other political actors at the EU level than other Western Balkan countries such as Serbia and Montenegro. Throughout the period 1999-2004, Croatia was not an official member state of the EU and had not yet had its application for membership confirmed. However, throughout the assessment and monitoring of the SAP, there were many interactions between parties at the domestic and at the European Level. A clear example of the socialisation of Croatian National Party elites is the Croatian SPD, the party which initiated a clear policy of Croatian integration into the EU after its parliamentary victory in 2000, which became an associated member of the Party of European Socialists in April 2004 (Fink-Hafner, 2007).

A further example is that Ivo Sanader – the President of the HDZ, who led the Croatian accession negotiations within the EU, created strong links with the European party federation the European People’s Party (EPP), of which it became a member of in 2002. The party’s reorientation under the EPP influence have included the intensification of bilateral contacts with EPP members, emphasizing the party’s European integration in addressing policy issues, proving that the HDZ shares the values and principles of the EPP (e.g. successful integration of national minorities – Serbs in Croatia) and the development of a network and regional cooperation with party counterparts in South East Europe (Sanader, 2006). All of these changes provide illustrations of visible Europeanization through the socialisation of national party elites, as they are examples of domestic change and party realignment which has been influenced by European Integration.

Voter Attitudes

This sub-section will concentrate on Croatian voters’ attitudes to integration with the EU, which is an excellent representative of whether Europeanization can influence a strong pro-European voter orientation. The time period previous to this chapter was marred with financial difficulty, particularly influenced by the loss of investors in the Croatian market. However, the EU’s SAP brought about a great deal of development, including; harmonisation of the law (e.g. upheaval of VAT law), reforms to education, new tax codes and financial support (European Commission, 2003). All of the aforementioned could arguably be deemed aspects of Europeanization and therefore factors that may have influenced voter attitudes in favour of European integration. Conversely, throughout the period discussed in this chapter, the EU’s pre-conditions for membership were amongst implementation and many citizens were subject to lifestyle changes as a result.

National survey data accumulated by the EU suggests that the Croatian electorate were supportive of EU integration and eventual membership. In data collected in 2003, almost 6 out of 10 Croatians believed that Croatia’s future should lie within the EU, even though at this time the pre-conditions were amidst implementation and an upheaval of the economy was underway. Further data stated that 82% of respondents who believed that Croatia should be a member state of the EU also saw Croatia’s future in a positive light, compared to only 70% of those who opposed EU membership (Eurobarometer, 2011). The citizens of Croatia in the aforementioned survey were informed of the EU’s preconditions, but still the majority showed support for European integration processes. It is imperative to conclude from this data that the prospect of EU membership at this time appeared to accompany positive attitudes to the country’s future.

Regarding the Croatian political parties, the Crobarometar survey in 2004 shows fluctuations in the support for the political parties in the Croatian party system (2004: Online). However, it has been publicised that the majority of the parties in the party system did at this time support European integration, particularly the centre left (SDP) and the centre right (HDZ) and that there was no obvious difference between the two parties concerning Europe. In conjunction with this, the SDP had also succeeded in admittance to NATO’s partnership for peace and the WTO– the first of the former Yugoslav countries to do so. The new government then was the recipient of generous European and American financial assistance which resulted in positive development through economic prosperity and welfare assistance for the citizens of the country. This further international integration may have affected the voter attitudes of the electorate in a positive light, as they may have seen this progress as a result of European Integration alone.

This attribution of the growth of the economy in this time solely as a result of EU assistance is incorrect, but still may have encouraged support for a pro-European campaign from voters.

igure 4 displays a rise in Euroscepticism and a decline in positive attitudes concerning accession at the end of the time period analysed in this chapter. This has consequently affected the party system, and there is evidence of protest voting for other parties such as the HSS, HSLS, HSP and HSL who were more sceptical about EU pre-conditions for membership. It appears that voter’s demands do play quite an important role in shaping the party system by offering pro-versus anti-European competition. For example, the HSP have attracted the Eurosceptic voters whilst both HDZ and SDP supporters are regarded as being more pro-European.

Overall, between 1999-2004, Croatian party system mechanics seem to have responded to dual pro-European pressures. It can be argued that the institutionalisation of the party system was beginning to be achieved due to stability of the core political parties, but not fully achieved due to the sheer drop in party identification by Croatian voters. The socialisation of national party elites is possibly the most visible example of Europeanization as Croatian parties have begun to form ties and links with European sector parties which have then influenced party policy within the country. An example of this is the SDP joining the Party of European Socialists and proceeding to position themselves on the centre-left rather than far-left of the political spectrum. The sub-section of voter attitudes is perhaps the most inconclusive as data collected by the independent Eurobarometer and independent Croatian research is contradictory. However, it is apparent that both a strong pro-European orientation and a strong anti-European orientation by voters are unable to directly impact the national party system in elections due to the proportional electoral system that was currently in place at this time.

CHAPTER 3: NATIONAL PARTY SYSTEM EUROPEANIZATION IN CROATIA FROM 2005-2013

This chapter will follow the same framework as the previous chapter, by using the structure of analysing national party system mechanics as created by Danika Fink-Hafner (2007). This construction will be used in the assessment of national party system mechanics in the time period between 2005 and 2013 in Croatia, after the country had its status as a future EU member state confirmed. It is hoped that through the analysis of institutionalisation, socialization and voter attitudes, a conclusion as to whether the causality of changes in the Croatian national party system can be attributed as a result of Europeanization can be reached. Furthermore, it is predicted that, as a result of Europeanization, the Croatian party system will be more institutionalised and the national party elites will be more socialised in this time-frame than the previous, due to the country having developed a far closer relationship with the European Union after the 2004 membership conformation.

The first key event in this time was the 2005 progress report conducted by the European Commission. In 2004, the European Council noted with satisfaction the progress made by Croatia in preparation for the opening of accession negotiations and as a result, the SAA between the EU and Croatia entered into force in February 2005. The SAA aimed to provide the legal framework for Croatian relations with the EU in terms of political dialogue and enhanced regional cooperation. Furthermore, its institutional framework provided a mechanism for implementation, management and monitoring in all areas of relations (EU Commission, 2005). The majority of the report appeared to conclude that Croatia had made good progress with its own organisational preparations for the accession negotiations and that this could be seen through increasing Croatian convergence to EU conditions.

In order to examine the national party system mechanics throughout this time, it is important to have a fundamental understanding of the changes in political governance and leadership, and the parties that held the most influence whilst the SAA’s were amidst implementation. Throughout this phase in Croatian history, there were only two Presidential elections that took place, in 2005 and 2011.

In 2005, joint candidate of the HNS, HSS, HLS and IDS parties Stjepan Mesic won the Presidency, with a second round voting majority of 56%. This was a re-election for Mesic, whom held the Presidency from 2000-2005. President Mesic was widely known for his activism in foreign policy, and his promotion of Croatian ambition to achieve membership for both the EU and NATO. In 2011 Ivo Josipovic, the SPD candidate, was supported by the HNS party, the IDS party the HSU party and the Greens. He won the Presidential election with 60.2% of the vote. Both Presidents who achieved power and a place in government at this time were supported by almost the same group of parties, showing little variation in the elections in this time period. However, it can be argued that the Presidential elections are a poor representation of Croatian change with regards to Europeanization because Presidents hold little power in terms of domestic governance – this position falls to the Prime Minister, who is elected in the Parliamentary elections.

For further examination of the political atmosphere in this time, we must look closely at the two elections of the Croatian Parliament, which took place in 2007 and 2011. In 2007 the governing centre-right Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) emerged as the winner of the election, despite failing to obtain an outright majority. The Croatian SDP, despite losing the election, achieved its best result in the percentage of votes they had gained, which was 31.2% [See Figure 5]. Other small parties lost seats, both the HSS and HNS parties lost four seats from the 2003 election and the Croatian Party of Rights suffered the heaviest election loss, losing seven seats and winning only one. This could be attributed to Europeanization as these smaller parties struggled to find EU support for some of their rather extreme policies towards immigration and nationalisation.

The 2011 elections were the first to be held after the conclusion of EU accession talks in June 2011. In 2011, voter’s ousted Croatia’s ruling HDZ conservative party, instead handing the centre-left opposition a strong mandate to modernize and overhaul the economy before the country joined the EU in 2013. The opposition party coalition, known as Kukuriki, which consisted of the main opposition parties in Croatia joining to form a pre-electoral coalition, won 83 seats in the 151 seat parliament. The ruling HDZ party gained 40 seats and consequently came second place. These statistics showed an interesting change considering the HDZ had previously ruled for 16 of Croatia’s 20 years as an independent state and once again could be attributed as a result of Europeanization.

This is because the SDP who were the key party within the Kukuriku coalition, had grown to achieve a strong relationship with the Party of European Socialists and consequently their political manifesto was altered to align with other members of the European Party Federations.

Institutionalisation of the National Party System

The institutionalisation of the national party system can be examined through its electoral volatility – the stability of the party system and the core political parties within it.Electoral volatility describes shifts of electoral support within the party system between two subsequent elections (Birch, 2001: 1). In other words, ‘the most predictable a party system is, the more it is a system as such, and hence the more institutionalized it becomes’ (Mair, 2000: 38). Weak party institutionalization can also be attributed to problematic democratic consolidation, as parties in such circumstances are unsure of their survival or stability in terms of electoral support. If there is a visible problem with democratic consolidation an argument could be made against the Europeanization of the national party system, as democratization is one of the key attributes the EU aims to promote through its accession criteria. In order to see a positive correlation of Europeanization as a result of further EU influence, it can be predicted that the core parties in the party system will remain more or less the same, and that their positions on the political spectrum will be more centre-orientated and mild, due to the lack of support for extremist parties within the EU.

In Croatia, there was a very low number of effective parties in the 1990’s which were determined by the existence of the HDZ as the dominant party. After the landmark elections of 2000, the effective number of parties has grown considerably. In both the 2007 and 2011 elections, the political and party landscape appeared to be stable, with the party system bipolar with two main actors – the HDZ and the SDP, in addition to some other minor parties. There appears to be a consensus about the future orientation of Croatia throughout the entire political spectrum with complete unanimity towards EU integration. The leading post-war party, the HDZ, has attempted to become more moderate and has moved towards the centre on the right-left axis towards becoming a standard conservative party [See Figure 6].

Even though the HDZ has strived to take on the appearance of a pro-European, pro-democratic party, it retains some relics of its nationalist past keeping it to the right of the spectrum. It has been asserted that one result of the Europeanization of western European party systems is a reduction in competition – a narrowing of competitive space – in the realm of policies (particularly economic), which may have also influenced the orientation to the centre of both main Croatian parties, the SDP and the HDZ.

In terms of party identification, there was a distinct lack of research for the time frame in this chapter resulting in a lack of ability to make any comparisons in this area between this chapter and the previous.

The European Socialization of National Party Elites

Regarding Europeanization, it can be predicted that the further Croatia will be under pressure to meet accession criteria, such as that identified in the 2005 progress report, the more socialized through Europeanization Croatian national party elites will become. Parliament members are part of the so-called political elites, which also includes executives and leaders of political parties, primarily those who hold a seat in the parliament. This sub-section will identify the further socialisation of national party elites through the links between national parties and European level party federations, to see whether more intricate partnerships have been formed as a result of the official membership conformation. It will also attempt to identify any changing party characteristics from the influence of EU party federations.

As mentioned in the previous chapter, interaction with other states or individuals is said to lead to shared conceptions of an identity of a role. Due to the fact that membership of the EU is expected to merge European political identities (Sedelmeier, 2005), much scholarship on identity and Europeanization has focused on ways in which European elites and institutions socialize candidate states into change (Johansson, 2002; Schimmelfennig 2005). Cooperation of the European political groups with political parties of the non-member countries is carried out in accordance with their political programs and closer relations are established between parties with similar political programmes. This can lead to the Europeanization of the candidate country political party, as often, issues related to the process of European integration are of particular importance for both sides.

Currently, European party links do not only include the main Croatian political parties, but also party youth organizations. The Croatian SDP Youth organisation joined forces with the Youth of the European People’s Party and the Democratic Youth Community of Europe in 2005, showing further European socialisation, particularly of those political elites of the future. The process of Europeanization can also in some aspects at least be seen in the more intensive contacts of leading party elite members (in particular from the Prime Ministers – Ivica Racan and Ivo Sanader) since the beginning of the accession stage. The President of the HDZ, the central party which led the Croatian accession negotiations with the EU, Sanader has placed an emphasis on not only the import of European values into his party through its links with the EPP, but also the use of these links for pursuing his party and country’s interests in relation with the EU. In a speech in 2006, he reiterated that ‘My answer to the question why I am so much in favour of the EU is because Croatia has always been a part of Europe. Croatia practices European values, and that has only been formalized by accession’ (Sanader, 2006). This theme of support for European policies became much more prominent after 2005, and all major parties on the political spectrum have begun to establish policies specifically related to the EU, such as the HDZ aiming to secure more EU funding in their most recent manifesto.

Voter Attitudes

In this time frame, when looking at the Croatian electorate, it is important to also keep in mind the unfinished transition, as well as a number of other features including the ongoing war tribunals. When the Croatian political scientist, Ivan Siber, analysed electoral behaviour since 1989, he concluded that it is not yet possible to bind the social structure with a political orientation, due to the process of transition, the institutionalisation of a new sovereign and independent state, and the war (Siber,1993). However, this sub-section will aim to identify patterns in Croatian voter’s attitudes towards Europe, and attribute as to whether or not these can be seen to be influenced by Europeanization.

Perhaps the most obvious example of voter attitudes towards EU integration would be the national referendum on Croatian membership of the EU, which took place in 2012. Two-thirds of Croatian’s voted in favour of the membership, but turnout was only 43.5% (welection, 2013).

Although this referendum passed by a clear majority, the HKDU party were the only party to stand for slower European integration, launching campaigns against membership and confirming the idea that the Croatian right were Eurosceptic.

However, Eurobarometer shows that the share of citizens who were against accession remained much the same throughout this time [See Figure 7]. Surveys and focus groups showed that an important determinant of the Euroscepticism among Croatian citizens was their perception of the EU’s political relationship with Croatia. The most common argument against the EU that participant mentioned was the perceived unfair treatment of Croatia during the accession process (Franc, 2013). In both 2009 and 2010, Gallup’s research showed that more people were against that in favour of EU membership. In fact in 2010, the support for EU membership was at an historic low – only 25% of the population supported EU membership. This changed only in 2011, when 44% were in favour and 37% against (Gallup Monitor, 2010).

These attitudes were to a large extent influenced by relationships between the country and the ICTY, alongside bilateral disputed with neighbouring EU countries: Slovenia (about Piran Bay) and Italy (about the Ecological and Fisheries Protection Zone). In addition, more than 70% of Croatians believe that their country was in a subjugated position during the process of negotiations with the EU (Crobarometer, 2011). Moreover, there was a lack of information about the EU accessible for Croatian voters as the majority of the negotiations took place between specialized groups of politicians, bureaucrats and experts, and were kept behind closed doors.

Furthermore, in 2013, Croatia held their first EU elections, which were an exceptionally low 20.84% – the lowest turnout in any EU election bar Slovakia (Gallup-Monitor, 2010).. However, very low turnout in EU elections has appeared to be the norm in the newest EU states, where enthusiasm for becoming members has been unable to translate into interest in the EU parliament. Therefore, this turnout could be seen as an example of Euroscepticism. However, both Presidents’ elected in this time period were pro EU, emphasising membership and further integration in their campaign manifestos, showing a still prominent pro-EU voter orientation (Kukuriku, 2011).

Overall, in this time frame there appears to be a deeper institutionalisation of the national party system present, with many parties conforming to a more centre orientated position and pursuing pro-European interests. For those parties who do not take a stance on the EU, there has been a loss of support unless a coalition with a pro European party is formed. A clear example of this is both the HNS and HSS parties, who have had to form the Kukuriku coalition in order to keep support. Further, the socialization of national party elites has continued with many Croatian youth organisations also becoming members of European party federations. Alongside this, among elites there has been a much more positive rhetoric involving the EU, particularly by the Presidents of the two key parties in the Croatian system. On the other hand, voter attitudes in this period have appeared to become more Eurosceptic, and opinion polls suggest that in the next election the majority of support will return back to the HDZ, who although are a pro-European party, campaign for slower European influence than the SPD. It can also be argued that since Croatia has become a member state in this time period, the impact of Europeanization may change post membership as it now becomes a two way process, both uploading and downloading.

Conclusion

This project has aimed to provide an evaluation of National Party System Europeanization, through focusing on a case study of Croatia, the newest member state of the EU. In order to enable further analysis, this project has investigated the Europeanization of the Croatian party system from 1999-2004, contrasting it to the time period 2005-2013 when Croatia gained eventual EU membership. This comparison has allowed the exploration as to whether there is a significant difference visible as Croatian politics become subject to further European influence. Furthermore, this project has also paid close attention to the institutionalisation of the national party system, the socialisation of national party elites and voter attitudes towards changing European influence. The previous attributes have all assisted in the provision of a fundamental analysis as to the extent of the effects of Europeanization and how the impact of this is visible through change in party system mechanisms.

Croatia’s transition and consolidation have been marked by its recent wartime experience and the states success in achieving EU membership is likely to encourage other candidates and potential candidates in the post-Yugoslav area. In addition, the fact that a country of the Western Balkans has completed its EU reforms to a level deemed sufficient for full membership, will certainly play a positive role for the remaining countries of the region. Often, European Union membership can provide states with a chequered history a chance to modernize and democratize through EU membership conditionality.

The academic emphasis on Europeanization in this project reflects the ‘deepening’ of European integration since the late 1980’s and the resultant research interest in the possible causal significance of the EU for domestic change. Tanya Borzel’s explanation of top down Europeanization has been extremely useful in underpinning the research of this project, through emphasising the significant impact the EU has had in instigating changes where member states themselves have not pre-empted external pressures for reform (Borzel, 1999). The ‘top-down’ explanation of Europeanization has also proved extremely useful in explaining the changes to national party systems as a result of indirect pressures exerted by the EU on the Croatian state.

The analysis of the institutionalisation of the Croatian national party system has created a strong positive correlation between institutionalisation and Europeanization. Robert Ladrech has maintained that ‘the continuing degree of party system institutionalisation in most post-communist party systems can be partly explained by the development of stable linkages between party policies and voter presences, due to the repositioning of political parties before and after accession’ (2009: 17). In both time frames, the party system can be argued as being institutionalised, as there were several core parties that retained the majority of support in the party system. In addition to this, a number of other smaller parties, such as the Croatian Party of Rights also lost a great deal of support and the percentage of votes they gain at elections continued to decrease. Furthermore, both main Croatian parties, the SPD and the HDZ have moved towards the centre of the political axis as a result of European influence. These are all examples of institutionalisation of the national party system, which can be attributed to Europeanization as the EU does not provide a great deal of support for extremist parties. Party identification is contradictory in the period from 1999-2004, but there is a lack of data available in this area between 2005-2013 meaning that no conclusions can be reached regarding this area of institutionalisation. Alongside this, the results regarding party identification in Chapter 2 cannot only be attributed as a result of Europeanization as there were a number of other variables such as electoral change that may have influenced the results.

In terms of the socialization of national party elites, the results throughout this project show that in both time periods Croatian party elites have begun to establish relationships with EU party federations. These relationships are often key in influencing party values at the national level, as European party federations often dictate manifestos. The central example of this is the Party of European Socialists and their influence on the Croatian SPD. As a result of this relationship and a change to the SPD manifesto, the party have initiated a move away from the Trade Unions that they previously relied on for support. Furthermore, throughout the past fifteen years, central party leaders such as Ivo Sanader, have also began to use the EU as a strategic tool in their speeches to the Croatian electorate.

The sub-section of Voter Attitudes to European integration is the only aspect of this project deemed to be inconclusive through the fact that the data in this area is contradictory. In Chapter 2, the data collected regarding Euroscepticism by voters is a direct contrast between the Eurobarometer (data collected by the EU) and the Crobarometer (data collected by the Croatian state). Furthermore in the recent EU parliament election discussed in Chapter 3, electoral turnout was undeniably low and Euroscepticism appears to be growing, but these facts cannot directly be attributed as a result of Europeanization. This is because voter attitudes are easy influenced by many other factors; economic stability, family ties, dissatisfaction with the national government.

The lesson that this project has established is that because EU membership is conditional on states meeting certain standards, there is a distinct pressure for reform on candidate countries even before they are EU member states. The problem with the application of Europeanization to Croatian national party systems is that not all changes can be attributed directly to influence from the EU. Although there are positive changes within the system, such as institutionalisation, socialisation, modernization and democratization, Croatia throughout the past 15 years has also been subject to influence from other Western organisations such as NATO and the WTO.

Ultimately, this project has successfully concluded that national party mechanisms change their norms, practices and procedures through Europeanization because they have calculated that it is utility-maximising to do so. Therefore, financial and technical assistance offered by the EU, alongside the other positives of membership, enables EU norms and reformation to become plausible for the member states, and as a result they begin to alter party mechanisms. It can be concluded that Croatia has been subject to national party system Europeanization as the institutionalisation of the party system and the socialization of national party elites both appear to have progressively increased from Chapter 2 to Chapter 3. In terms of Voter Attitudes, there is further research that should be undertaken in this area as the data available is contradictory and therefore inconclusive.

Bibliography

Anastasakis, O., 2005. The Europeanization of the Balkans. Available from: http://www.sant.ox.ac.uk/seesox/anastasakis_publications/Anastasakis_Brown.pdf [Last Accessed 4 October 2013].

Bartlett, W., 2006. Croatia: Between Europe and the Balkans (Post-communist States and Nations). USA: Routledge.

Birch, S., 2001. Electoral Systems and Party System Stability in Post-Communist Europe. In: Paper presented at the American Political Association Meeting.

Borzel, T.A., 2003. Conceptualizing the Domestic Impact of Europe. In: Radaelli, C.M. and K. Featherstone(eds) – The Politics of Europeanization. New York: Oxford University Press.

Börzel, T.A. and T. Risse, 2004. One Size Fits All! EU Policies for the Promotion of Human Rights, Democracy, and the Rule of Law. In: Paper presented for the Workshop on Democracy Promotion organized by the Centre for Development, Democracy, and the Rule of Law, Stanford University, October 4-5.

Bulmer, S. and C. Lequesne, 2012. The Member States of the European Union, Second Edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bulmer, S. and C.M. Radaelli, 2004. The Europeanization of National Policy. Queens Papers on Europeanization. 1 (1).

Burnham, P., Gilland Lutz, K., Grant, W and Layton-Henry, Z., 2008. Research Methods in Politics Second Edition. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Council of the European Union, 2012. Council Decision: 2012/642/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against Belarus. Available from: “COUNCIL DECISION 2012/642/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against Belarus”. [Last Accessed 14 February 2014].

Croatia European Union Official Webpage, 2013. Available from: http://www.croatia.eu/article.php?lang=2&id=26 [Last Accessed 12 December 2013].

Cular,G., 2005. Izbori i knosolidacija demokracije u Hrvatskoj. Fakultet politickih znanosti. Zagreb: Sveucilista u Zagrebu.

Delegation of the European Union to the Republic of Croatia. Available from: http://www.delhrv.ec.europa.eu/?lang=en&content=62 [Last Accessed 29 January 2014].

Duverger, M., 1972. Factors in a Two-Party and Multiparty system – Party Politics and Pressure Groups. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell p. 23-32

Enyedi, Z., and P.G. Lewis, 2006. The Impact of the European Union on Party Politics in Central and Eastern Europe. In: Lewis, P., and Z. Mansfeldova (eds)- The European Union and Party Politics in Central and Eastern Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

European Commission, 2005.Croatia 2005 Progress Report. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/archives/pdf/key_documents/2005/package/sec_1424_final_progress_report_hr_en.pdf [Last Accessed 19 February 2014].

European Union Institute, 2010. Available From: http://www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Research/Media/eup/parties.html. [Last Accessed 20 March 2014].

Featherstone, K. and C. Radaelli, 2003. The Politics of Europeanization. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fink-Hafner, D., 2007. Factors of Party System Europeanization: a Comparison of Croatia, Serbia and Montenegro. Available from: http://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/6343 [Last Accessed 1 March 2014]

Fink-Hafner, D., and A. Dezelen. 2007. The Democratisation and Europeanization of Party Systems. Available from: http://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/6341/ssoar-pceur-2007-12-fink-hafner-the_democratisation_and_europeanisation_of.pdf?sequence=1 [Last Accessed 28 February 2014].

Gallup Balkan Monitor, 2010. Survey Data: Insights and Perceptions: Voices of the Balkans. Available from: http://www.balkan-monitor.eu/index.php/dashboard. [Last Accessed 21 March 2014].

George, S., 2001. The Europeanisation of UK Politics and Policy-making: the Effect of European Integration on the UK. Queens Papers on Europeanization. 8 (1).

Gfk Hrvatska, 2006. Public Support for EU Accession in Croatia. Available from: https://www.askgfk.hr/index.php?id=7&L=hr. [Last Accessed 24 March 2014].

Franc, R. And V. Medjucorac, 2013, Support for EU Membership has Dramatically Fallen. Available From: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2013/04/02/croatia-euroscepticism/ [Last Accessed 20 March 2014].

Hague, R., and M. Harrop. Comparative Government and Politics, an Introduction. 7th edition. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Halperin, S. and O. Heath, 2012. Political Research, Methods and Practical Skills. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ipsos Puls, 2011. Stavovi hrvatskih grañana prema priključenju Europskoj uniji. Available From: http://www.delhrv.ec.europa.eu/files/file/vijesti/Ipsos_DEU_2011_hr_v2.pdf. [Available From: 24 March 2014].

Kelly, L., 2012. Belarus’s Lukashenko, Better a Dictator than Gay. Available from: http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/03/04/us-belarus-dicator-idUSTRE8230T320120304. [Last Accessed 20 March 2014].

Kukuriku, 2014. The Kukuriku Coalition Official Website. Available from: http://www.kukuriku.org/. [Last Accessed 14 March 2014].

Ladrech, R., 1994. Europeanization of Domestic Policies and Institutions: The Case of France. Journal of Common Market Studies. 31 (1), p. 278-304.

Ladrech, R., 2002. Causality and Mechanisms of Change in Party Europeanization Research. Keele: KEPRU Working Papers.

Ladrech, R., 2009. Europeanization and Party System Instability in Post-Communist States. Available from: http://www.keele.ac.uk/media/keeleuniversity/group/kepru/KEPRU%20WP%2027.pdf [Last Accessed 29March 2014]

Leuffen, D., Rittberger, B.and F. Schimmelfennig, 2012. Differentiated Integration: Explaining Variation in the European Union. USA: Palgrave Macmillan.

Liviu, A. and C. Anamaria, 2010. Croatia: Administrative Reform and Regional Development in the Context of EU Accession. Available from: http://www.rtsa.ro/en/files/TRAS-31E-6-IVAN,%20IOV.pdf [Last Accessed 14 October 2013]

Lukic, R., 2008. Croatia since Independence: War, Politics, Society, Foreign Relations. Croatia: Oldenbourg Wissensch.Vlg.

Mair, P., 2000. The Limited Impact of Europe on National Party Systems. West European Politics, 23 (4): p. 27–51

Mihalia, R., 2012. Europeanization Faces Balkanisation: Political Conditionality and Democratisation – Croatia and Macedonia in Comparative Perspective. European Perspectives – Journal on European Perspectives of the Western Balkans Vol. 4, No. 1 (6). [Last Accessed 1 March 2014].

Nugent, N., 2010. The Government and Politics of the European Union, Seventh Edition. USA: Palgrave Macmillan.

Olsen, J.P., 1997. Institutional Design in Democratic Contexts. The Journal of Political Philosophy. (5) p. 203-229.

Radaelli, C.M., 2000. Whither Europeanization? Concept stretching and substantive change. Available: http://www.eiop.or.at/eiop/pdf/2000-008.pdf. [Last Accessed 30 December 2013.]

Sanader, I., 2006. Transnational Parties in Regional Cooperation: The Impact of the EPP on Central and South-East Europe. European View, special issue on Transnational Parties and European Democracy, p.135–141.

Sartori, G., 2005. Parties and Party Systems. Colchester: ECPR

Schimmelfennig, F. And U. Sedelmeier, 2005. The Europeanization of Central and Eastern Europe. New York: Cornell University Press.

Searle, J., 2005. The Construction of Social Reality. London: Penguin Books. p.31-59.

Sedelmeier, U., 2011. Europeanisation in New Member and Candidate States. Available from: http://europeangovernance.livingreviews.org/open?pubNo=lreg-2011-1&page=articlese4.html [Last Accessed 14 March 2014].

Siber, I., 2006. Politicko ponasanje. Istrazivanje hrvatskog drustva. Zagreb: Zagreb University Press.

State Election Committee, 2007. Election Results of 2007. Available From: http://www.izbori.hr/2007Sabor/rezultati/rezultati_izbora_sluzbeni.pdf. [Last Accessed 10 March 2014].

State Election Committee, 2011. Election Results for 2011.Available From: http://www.izbori.hr/izbori/dip_ws.nsf/0/5740EBF523B42CE5C12579A3005AD353/$file/Izvjesce_o_provedenom_nadzoru_finaciranja_izb_promidzbe_Sabor.pdf. [Last Accessed 10 March 2014].

Storajova, V., and P. Emerson, 2010. Party Politics in the Western Balkans. New York: Routledge.

The World Bank Group. (2014). Croatia Data. Available: http://data.worldbank.org/country/croatia. [Last Accessed 20 February 2014].

Tomobe, 2011. Croatia Sabor Seats, 1999-2011. Available From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Croatia-Sabor-Seats-1992-2011.gif. [Last Accessed: 14 March 2014].

Udwin, E and J.C Filori, 2013. Croatia becomes a candidate for EU Membership – Frequently asked questions on the Accession Process. Available from: http://www.delhrv.ec.europa.eu/images/article/File/FAQcroatia04_14-06_en.pdf [Last Accessed 30 September 2013]

Wallace, H., W. Wallace and M.A. Pollock, 2000. Policy-Making in the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vataman, D., 2012. Croatia, the 28th Member State of the European Union. Available from: http://www.doaj.org/cks.univnt.ro/uploads/cks_2013_articles/index.php?dir=1_Juridical_Sciences%2F&download=cks_2013_law_art_082.pdf [Last Accessed 15October 2013].

Volkens, A., O. Lacewell, S. Regel, H. Schultze and A. Werner, 2010. The Manifesto Data Collection: Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

Vukovar, A., 2008. Croatian Defence. Available: http://cascarino.homestead.com/. [Last Accessed 6 March 2014].

Vujovic, Z., 2007. Europeanization of National Political Parties and Party System: Case Study of Montenegro. The Journal of the Central European Political Science Association 3, (1). p. 51-70.

Zidaric, Z., 2010. Adding a New Dimension to the Political Spectrum. Available From: http://www.domovod.info/entry.php?48-Adding-a-new-Dimension-to-the-Political-Spectrum. [Last Accessed: 20 March 2014].

Appendices

Written by: Janeeth Devgun

Written at: University of the West of England, Bristol

Supervised by: Dr Gunter Walzenbach

Date Written: April 2014

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Australia on the United Nations Security Council 2013-14: An Evaluation

- Terrorists or Freedom Fighters: A Case Study of ETA

- Ontological Insecurity: A Case Study on Israeli-Palestinian Conflict in Jerusalem

- Water Crisis or What are Crises? A Case Study of India-Bangladesh Relations

- Does Presentism Work? An Evaluation of the Memory Politics of Fidesz

- The Tension Between National Energy Sovereignty and Intra-European Solidarity