Lebanese feminism cannot be understood unless contextualized within the postcolonial legacy that shapes politics in Lebanon and regulates its political discourse. This factor, which is common to other postcolonial societies, creates especially complex problems for feminists, who are continually being reminded, as they attempt to make their claims, that their discourse emanate from the mindset of the Western colonial powers. A history of colonialism and the existence of long-term Western hegemony in the Middle East mark all political and social movements in the region, which not only look inward towards achieving change in a given community or state, but also look outwards, to the West, inasmuch as the West provides both resources and limits.

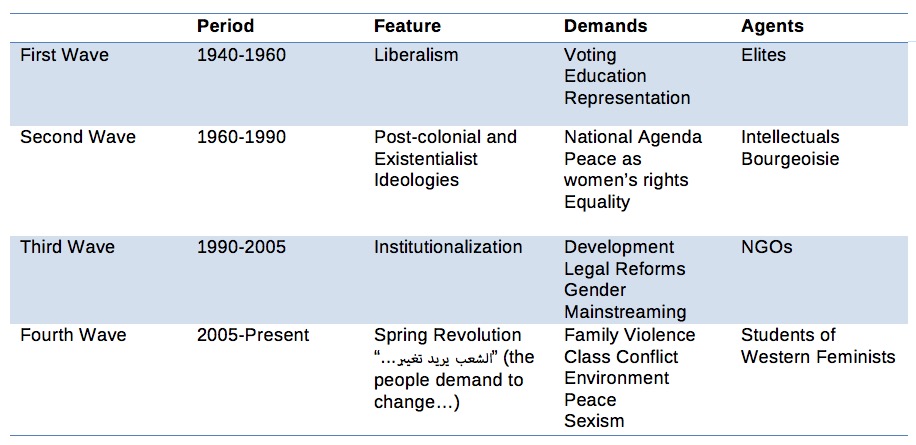

While American feminism has produced a historiography that traces the movement through different waves, rarely do we hear a discussion of waves of women’s rights activism or feminism in other parts of the world, which I argue exist at least in the Lebanese contexts. Waves are linked concretely to changes in the collectivity both of activists and of the social context in which they are acting. In fact, a discussion of feminist waves from a Lebanese perspective—summarized in the chart below—might be helpful to understanding the connections and temporal lags binding together the global struggle for women’s rights.

The First Wave

Lebanese feminism emerged with the pioneers (Raedat) who lived in the 1920s (Nisaa al Ishrinat). These women’s feminism was influenced by the enlightenment movement in Europe, the struggles with colonialism in the third world and the Middle East, and the social changes brought through Western missionaries, as well as Ottoman and Egyptian attempts for emancipating women. As European missionaries accompanied the European colonists into Asia, Africa, and the Americas, they carried with them a literature that carried the cautiously subversive message of education for women and their liberal ideologies. The “woman question,” as it was called, created an enormous amount of interest and controversy in Ottoman Turkey, as well as having echoes elsewhere in the Middle Eastern world.

Thus, the first wave of feminism in the Middle East found its supporters and creators among a level of elite women (as well as men) who were dedicated to a public life of charitable activism, part of which concerned the education of women and the improvement of their roles as mothers (Stephan, 2012). Against this background, it is no surprise that the first wave of Lebanese feminism had an elitist provenance, and was connected to a liberal ideology and religious reformism. As Lebanese society adapted to a print culture and a higher degree of emphasis on education and commerce, the first Lebanese women’s rights activists attempted to take advantage of these openings in journalism, educational programs, and charity organizations.

During the first wave of feminism in Lebanon, a major focus of activity was the establishment and running of charitable organizations, al-jam‘iyyat al-khayriya, that have sustained the presence and the historical leadership roles of an advanced feminist cadre. It was this group, and those they influenced, that concentrated on increasing women’s participation in public life through education and vocational training (Hijab 1988, 144). By the early twentieth century, women were extensively involved in charitable organizations as an opportunity to participate in public life without violating social norms and expectations. As women’s roles changed radically in a number of Middle Eastern states in the 1920s – in Egypt and Turkey, for example – the effect was felt in Lebanon.

The Second Wave

The end of first wave of feminism coincided with the era of nation-building that accompanied the establishment of the First Lebanese Republic in the years following independence from the French Mandate in 1943. These years featured competition between the various ruling families and continuous interference by foreign powers, especially France and Britain. In the late forties, an influx of Palestinian refugees from Israel was put in camps in Lebanon, initiating a situation that led to many conflicts within Lebanon between different factions. Eventually the constitutional compromise that had divided power between different denominations and ethnicities could not keep the peace, especially in the light of conflicts in areas close to Lebanon.

By 1947, two major women’s advocacy groups existed in Lebanon. The first group was the Lebanese Women Union, which was founded in 1920 in order to bring together Arab nationalists and leftists. The second group, the Christian Women’s Solidarity Association, was founded in 1947 and composed of elites and haute bourgeoisie women representatives from twenty Christian organizations throughout Lebanon. In 1952, both camps decided to form a permanent organization known as the Lebanese Council of Women. Political advocacy for women’s rights in Lebanon began with the Council’s fierce fight to obtain suffrage rights for women. The Council sustained an effective and united campaign and pressured the government to grant all Lebanese women voting rights on February 18, 1953 (Stephan 2010a). Upon obtaining the right to vote and be elected in 1953, one of the Council’s founders, Emily Fares Ibrahim, announced her candidacy for the 1953 parliamentary elections, but she was not elected [1]. However, later that year, three Council members were selected to Beirut’s City Council (Chkeir 2002, 57).

During the sixties and seventies, a number of political parties in Lebanese (especially communist and leftist) established committees for women in order to discuss their issues and raise their awareness (Stephan, 2012). Out of these committees, several women’s organizations were born, including the Women’s Democratic Gathering and the League of Lebanese Women’s Rights. The influence of socialism on Lebanese feminists of that era is noteworthy. However, the Lebanese Civil War broke out in 1975 as a direct result from the escalating tension between Palestinian refugees and the Christians, which the Syrians saw as an invitation to intervene. The war years were not propitious for pushing for civil rights for women; rather, activist energy turned to trying to negotiate a peace and end the debilitating and ferocious violence. The second wave of feminism was born in a climate filled with political tension, which left its mark on its mission and self-understanding. To the struggle for rights and justice was added the struggle for peace and security.

The idealism of the sixties was one of the victims of the 15-year civil war, during which the arming of all sides and their violent confrontation pushed women’s issues to the side. Women’s organizations that had been set up for peaceful struggle in the public sphere for civil rights were transformed by circumstances into agencies that disperse welfare services to the refugees and war victims. Evelyne Accad viewed feminist organizations as a non-tribal, non-interventionist model for making Lebanon a nation:

In Lebanon, both the outside forces – the Syrian and Israeli occupations, the big powers’ interferences, the Palestinian desperate struggles – and the inside tribal wars have equally brought the crisis to its peak. It is therefore necessary to work at solving both aspects of the conflict in order to reach results. The resolution of opposition between these two sides can be compared to the feminist association of the otherwise opposed personal and political realms, an association that has acquired even greater meaning in the present Lebanese situation.

All activities focusing on women’s rights were dismissed, and the Lebanese Women’s Council that was formed shortly before the conflict started became inactive.

The Third Wave

The launching of the United Nations’ Decade for Women in 1975 during the first World Conference on Women, held in Mexico City, marked the beginning of a global feminist initiative that took more seriously the voices of Third World feminists, who were positioned so as to debate and collaborate with their Western colleagues on more equal terms (Mohanty, Russo and Torres, 1991). In 1979, the General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), which is often described as an International Bill of Rights for Women. In 1985, the World Conference to Review and Appraise the Achievements of the United Nations Decade for Women: Equality, Development and Peace was held in Nairobi. The conference, which called together representatives of different governments, was paralleled by an NGO forum that was attended by 15,000 representatives of non-governmental organizations (NGOs). This event, which the United Nations describes as “the birth of global feminism,” founded the UN Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM). The Fourth World Conference on Women, held in Beijing in 1995, went a step further than the Nairobi Conference to assert women’s rights as human rights and to demand that member nations commit to ensuring respect for those rights. CEDAW and Beijing were significant because countries, including Lebanon, that signed on to CEDAW entered into an agreement to hold themselves accountable to the Convention’s directives.

The UN conference on women in Beijing marked the birth of the third wave feminism in Lebanon. This wave’s feminists took advantage of the augmented global attention to, and funding for, gender-related issues to launch those projects definitive of their third wave of feminism. In the 1990s, international organizations’ efforts brought the Lebanese government to form a partnership with women’s organizations in order to provide social welfare services and design the future of gender relations in the country. Activists in the various advocacy groups used this political opportunity to reach out to women of all denominations and ethnicities and increase their political awareness as they advance the laywoman’s attainments of education, work, and political rights (Stephan, 2012). This was the era of institutionalizing women’s organizations and introducing gender activism to the Arabic lexicon.

On June 27, 1990, a delegation from the Human Rights Association, headed by feminist Laure Moghaizel, visited the prime minister and proposed including a clause in the new Lebanese constitution to emphasize Lebanon’s commitment to the International Declaration of Human Rights (Nassif 1998). The Lebanese government adopted the Association’s recommendation and gave supremacy to international treaties over Lebanese law. This action has proved useful to contemporary activists, who apply this clause today to negotiate legal reforms based on its discrepancies with international treaties.

Thanks to the efforts of Laure Moghaizel and the Association for Human Rights, Lebanon officially gave jurisdictional authority to international treaties if they come into conflict with national law. The fact that many of the issues addressed in CEDAW are not mentioned in the Lebanese law indicates that Lebanon still lags behind the progressive CEDAW agenda. This lag gives woman’s rights organizations a clear mission: to agitate both for the enforcement of existing law and compliance with that part of the CEDAW agenda which Lebanese law does not recognize (Stephan, 2010a).

Guided by this mission, a number of structured and independent advocacy associations developed within the sphere of the women’s rights movement, creating a contrast between their discourse and goals and that of the confessional charitable system. By the end of the twentieth century, advocacy women’s organizations, al-jam‘iyyat al-matlabiya, were formed throughout Lebanon (Stephan, 2012). Lebanese women’s rights organizations organized themselves under two major coalitions that fall under the Lebanese Council of Women.

The first coalition is the National Coalition to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination against Women, founded in March 1999. The Meeting lobbies to implement the principles stated in the Lebanese constitution and in CEDAW and to reform the Lebanese personal status laws, and it has racked up some success in modifying certain labor and trade laws that discriminated against women and in changing the terminology of the social security laws to take out language discriminatory to women. The second coalition is the Lebanese Women’s Network, which was constituted in 2001 from connecting thirteen feminist organizations under the leadership of the Women’s Democratic Gathering. Its aims are to promote “complete equality” between men and women by eliminating all forms of discrimination and establishing a cooperative and empowering environment (Stephan, 2012).

Outside these two networks are notable women’s rights organizations such as the League of Lebanese Women’s Rights, which was founded in 1970 with the goal of defending women’s rights in all Lebanon including the rural areas. Its work involves political lobbying of women’s issues in parliament, encouraging women’s political participation, and initiating dialogue among the various political and social groups on the local level (Stephan, 2012).

The 1995 United Nations Conference on Women in Beijing also stimulated the formation of two organizations: the National Commission for Lebanese Women (NCLW) and the National Committee for the Follow Up of Women’s Issues. The NCLW was first created to prepare for the Beijing Conference in 1995 as the official Lebanese representatives to the UN. It was composed of members from both the governmental and nongovernmental sectors. After the conference, the year 1996 saw the NCLW become the official body responsible for monitoring the implementation of resolutions taken in Beijing. As of 2003, the First Lady heads the Commission and collaborates with a team of appointed women specialists. Likewise, the National Committee for the Follow Up of Women’s Issues was established in 1996 following the Beijing Conference. It is a nongovernmental entity that coordinates a network of various nongovernmental organizations that share the mission of promoting women’s participation in social, political, and economic fields, abolishing discriminatory barriers that impact upon women’s participation in the public sphere (Stephan, 2012).

Other members of the Lebanese Council of Women include organizations that more narrowly target issues of concern to women. Some focus on women’s rights in the labor force (e.g. the Working Women League), others through education and research like the Lebanese Association of Women Researchers (Bahithat), and a third group utilizes international development projects to improve women’s status in Lebanon such as the Collective for Research and Training on Development-Action (CRTD-A). Finally, a significant women’s rights organization, Lebanese Council to Resist Violence Against Women (LCRVAW) was established in 1997 as a response to the alarming rate of violent acts against women, and both publicizes violence against women and lobbies politicians to reform laws and procedures that make rape, honor killing, and assault acceptable, while providing services for victims, from hotlines to legal counseling and advocacy for women in courts. These organizations made the personal political, by bringing taboo topics such as domestic violence and sexuality to the public arena thus paving the way for the fourth wave feminism to emerge, as we shall see next.

The Fourth Wave: The Spring Revolution

The uneasy balance of power in Lebanon between Syrian troops and allies and Lebanese forces was overturned in favor of the Lebanese due what became known as the Spring Revolution or the Cedar Revolution. In March 2005, Lebanese civilians, in protest against the assassination of Rafik Hariri, demonstrated massively pressuring Syria to withdraw its troops from Lebanon. A United Nations resolution followed that in essence enshrined Lebanon’s right to full national sovereignty without outside interference. Observers inside and outside Lebanon noted the much enlarged role played by Lebanese women in these events, which energized political activism among women where it had, perhaps, grown tired. By openly protesting in the streets and nonviolently resisting the Syrian occupation, these women in essence added a feminist dimension to the liberation of Lebanon (Stephan, 2010b).

That year, 2005, was a year of turmoil in other spots in the Middle East than in Lebanon: notably, it was the second year of the American occupation in Iraq, when the war started heating up. And in 2006, things turned worse when Israel’s incursion into Lebanon turned into a defeat, making Hezbollah a more powerful and respected force in Lebanon. Fallout from the twin factors of a Shiite gain in Iraq and Hezbollah’s rise in status were felt as far into the future as 2011, when Najib Azmi Mikati, with Hezbollah’s support, was elected prime minister.

In this era, the rhetoric of global and multicultural feminisms seemed especially salient. Some feminists saw opportunities for the woman’s rights movement in the unstable situation in the Middle East, as old autocratic structures were falling and old alliances were coming apart. Some women’s organizations, like the Collective for Research and Training on Development-Action (CRTD-A) and KAFA, became a bridge between the third and fourth waves of Lebanese feminism. For instance, the CRTD-A, initiated in 1999, has a regional focus across the Arab world – primarily in Lebanon, Yemen, Egypt, Syria, Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria. It focuses on social development of local communities and organizations and on enhancing gender participation and developing women’s capacities (Stephan, 2012). Like CRTD-A, KAFA (‘Enough’) sprang out of LCRVAW in 2005 as a nonprofit, nonpolitical, and nonconfessional civil society organization. Its aims were to mitigate the causes and results of violence and exploitation of women and children through advocacy and lobbying, raising awareness, and offering social and legal services to vulnerable cases.

New organizations emerged in this era focusing on raising awareness of domestic violence and protesting the vulnerability of its victims in the legal system. They partnered up with activists struggling to seek legal protection of constituents who were not previously represented like migrant workers and sexual minorities. Taking on issues such as domestic violence and abuse of female domestic workers, as well as issues like the environment, women’s art, male-centered knowledge, and sexual diversity, organizations like Nasawiya in the post-2005 era use social media as a mean to disseminate information, recruit supporters, and raise awareness. Nasawiya’s website proclaims its opposition to a set of enemies that would be familiar to Western feminists: sexism, classism, heterosexism, racism, and capitalism. Claiming their voice as the subalterns in the Lebanese society and the Lebanese women’s rights movement, they aspire to give voice to the voiceless in the Lebanese society:

We strive to not only be a movement of educated and privileged women, but a movement by and for the single mothers, the refugees, the disabled, the sex workers, the migrant workers, the people of non-conforming gender identities and non-conforming sexualities, etc… [H]aving been united in marginalization, we can make an effort to unite in seeking a change in ourselves and in our society.

Nasawiya sees the current state of sexism as the expression of the still predominant feudal/patriarchal Lebanese culture and demand non-judgmental sexual health services and sexual education. Its members also want to eliminate all forms of harassment and gender-based violence. Considering equal rights of employment and equal treatment and pay in the workplace as a fundamental right, they demand that it be extended to domestic migrant workers who currently hold minimum rights in Lebanon and the Arab World.

Focusing on empowering each other, these feminists are promoting a positive self-image and are asserting their right to their bodies and their sexualities. They specify this right as the right to choose who to marry and whether or not to undergo an abortion. Internally, they are embracing responsible consumerism, protecting the environment, micro-financing, and economic sustainability. They also are urging women to seek full citizenship rights and to play an active role in the political process. By supporting other feminists in the Arab world, the Global South, and the rest of the world, these feminists are participating in the efforts to promote feminist art, women-friendly media, and women’s studies courses and institutes.

Nasawiya partners with organizations like KAFA and Beit el-Hanane on the issue of domestic violence. KAFA, which is mentioned above, aims to achieve a democratic and just society that is free from violence and exploitation (Nasawiya website). Likewise, Beit el-Hanane (Home of Tenderness) was established in 2008 to support women victims of abuse. It promotes community awareness and education. It also supports gender based violence survivors emotionally, psychologically, and physically through its counseling centers (Beit el-Hanane website).

In this regard, one of the new features of the current feminist landscape is a more forthright stance on gay and lesbian issues. Lebanon stands in the lead of countries in the region that have had a GLBT organization. Since its establishment in 2004,

Helem [has led] the peaceful struggle for the liberation of Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals and Transgendered (LGBT), and other persons with non-conforming sexuality or gender identity in Lebanon from all sorts of violations of civil, political, economic, social, or cultural rights.

Another organization, established in 2007, is Meem, which includes 350 lesbian, bisexual, queer women and transgender persons (including male-to-female and female-to-male). With a similar focus as Helem, Meem is based on values of self-empowerment, mutual support, confidentiality, and respect through self-organizing.

In the same vein, the Anti-Racism movement uses social media to documents violations against domestic workers. It presses charges against employers who endanger or abuse their domestic workers on a regular basis and organizes marches to protest the system under which the migrant laborer has to operate, and to press for accountability, monitoring, and anti-discrimination laws. As partners of the movement, women’s organizations were instrumental in organizing the April 29, 2010, march by recruiting participants through domestic and professional channels.

Traditionally, feminist activists relied on kinship ties, face to face relationships, and, to a certain extent, educational institutions in order to organize. The fourth wave of activists is more comfortable with internet social media, giving them a more immediate contact with other global and Arab feminists. Despite adopting a progressive platform, these activists expand the feminist approach to one that seeks inclusiveness beyond the Western oriented elite, as well as those who are involved with progressive politics.

As this survey of the four phases of Lebanon’s feminist history indicates, the women’s rights movement is connected to the Lebanese social space and reflects its shifts, while receiving and selecting certain theories, models, and practices from the West and other places in the global context. Lebanese feminism thus articulates the symbolic and practical interaction between local and global forces at every historical conjunction. Lebanese style of activism, while sometimes attempting to shape the parameters of Lebanese governance, has more often taken the course of “small steps” advocated by Laure Moghaizel, remaining within the parameters of Lebanon’s political, religious, and social structures and seeking to overcome local political cleavages, accommodate foreign interests, and take advantage of political opportunities that create openings to advance women’s rights.

The vast crowds of the Cedar Revolution have long gone, as Lebanon sits on the sidelines, anxious about a new civil war that seems to be spilling over from the conflict Syria. However, the Arab Spring has encouraged a certain amount of activity in the streets of Beirut. New social media outlets have provided a new outlet and a relatively safe space for these feminists to express their dissidence and discuss taboo issues like family violence and sexuality. The internet, Facebook, and Twitter have also become tools used by previously marginalized individuals and, in particular, disaffected youth to organize collectively and mobilize online to raise awareness of sexual diversity in the Arab world.

Notes

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the views of, and should not be attributed to the U.S. Department of State.

[1] According to Joseph (2000), between 1953 and 1972, seven women ran for parliament, but were unsuccessful. However, in 1960 Mirna al-Boustani al-Khazan Hikma was elected to complete the remaining 8 months of her father, Emile Boustani.

References

Chkeir, Iman C. 2002. Nisa’ fi imra’a: al-sirat Laure Moghaizel. Beirut: Annahar Publishing. Dibo, Amal. 1997. Interview with Laure Moghaizel in Beirut, Lebanon.[***this can be inserted directly in the text; interviews don’t have to be included in a bibliography]

Hijab, Nadia. 1988. Womanpower: The Arab Debate on Women at Work. Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Joseph, Suad. 1997b. “The Public/Private—The Imagined Boundary in the Imagined Nation/State/Community: The Lebanese Case.” Feminist Review[***issue no. is missing], 73–92.

Joseph, Suad 2000. Gender and Citizenship in the Middle East. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Joseph, Suad and Suan Slyomovics. 2001. Women and Power in the Middle East. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Mohanty, Chandra, Ann Russo and Lourdes Torres. 1991. Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism. Indiana University Press.

Moghaizel, Laure. 1985. al-Mar’a fi-l-tashri‘ al-lubnani fi daw’ al-itifaqiyat al-duwaliya ma‘ muqarana bi-l-tashri‘at al-‘arabiya. Beirut: Institute for Women’s Studies in the Arab World, Lebanese American University.

Moghaizel, Laure. 2000. Huquq al mar’a al-insan fi Lubnan: fi daw’ itifaqiyat al-qada’ ‘ala jamyi‘ ashkal al-tamyeez did al-mar’a. Beirut: The National Commission for Lebanese Women and Joseph and Lore Mogheizel Foundation.

Nassif, Nicolas. 1998. Joseph Moghaizel: The Journey of Love and Struggle. Beirut, Lebanon: Joseph and Laure Moghaizel Foundation.

Stephan, Rita. 2012. “Women’s Rights Movement in Lebanon” in Mapping Arab Women Movements: A Century of Transformation from Within edited by Nawar Al-Hassan Golley and Pernille Arenfeldt. American University of Cairo Press.

Stephan, Rita. 2010. “Couples’ Activism for Women’s Rights in Lebanon: The Legacy of Laure Moghaizel.” Women Studies International Forum 33:533–41.

Stephan, Rita. 2010b. “Leadership of Lebanese Women in the Cedar Revolution.” In Muslim Women in War and Crisis: Presentation and Representation, edited by Faegheh Shirazi. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Gender as a Post-Conflict Condition: Revisiting the Three Waves

- Opinion – COVID-19’s War on Feminism in the U.S.

- Introducing Feminism in International Relations Theory

- Transnational Feminist Networks and Contemporary Crises

- Opinion – Coming in from the Soviet Cold: Feminist Politics in Kazakhstan

- Opinion – A Feminist Foreign Policy for India: Where to Turn?