The Cold War ended with hopes and expectations about the possibilities of a new world order. It facilitated the resolution of half a dozen lingering conflicts in Central America, Asia and Southern Africa and a renaissance of sorts in the United Nations (Murphy and Weiss, 2012: 116). President George H.W. Bush foresaw the advent of an era freer from the threat of terror, stronger in the pursuit of justice and more secure in the quest for peace, in which all the nations of the world could live and prosper in harmony (Bush, 1990). These hopes and aspirations were short lived as ending the Cold War failed to bring an end to conflicts; instead it paved the way for more striking issues like identity, liberation, nationalism, terrorism, national self-determination and religion to constantly trigger instability and insecurity. Specifically, the emergence of nationalism as a force in Eastern Europe raised the problem of the relevance of domestic factors in the relations between states and the relevance to security of the internal structure of states against the traditional emphasis on the international, heralding a more complicated scenario, where for every local war that ended at least one new one erupted (Murphy and Weiss, 2012: 116). The fragility of the state regarding central issues in international security was further exposed in the face of complex forces and new forms of violence interlinking local political conflicts and organized crime. Internationalized disputes show that violence is a problem for the rich and the poor, with more than 80 percent of fatalities from terrorist attacks over the last decade happening in the non-western hemisphere (World Bank, 2011: 5).

Attacks in one region can impose costs on all through global markets, for example in the four weeks following the beginning of the uprising in Libya, oil prices increased by 15 percent, so also the attacks of ISIS on sensitive Iraq oil sites. Michael Brown (2003: 1) noted that in the twentieth century, armed conflicts killed tens of millions of people, wounded tens of millions of people, and drove tens of millions of people from their homes. Accordingly, international terrorism appeared to be the major challenge to global peace at the very beginning of the 21st century including terrorist groups like al-Qaeda and the Taliban. Currently international security is challenged with issues of terrorism that start as a very simple insignificant religious problem and grows larger into a borderless phenomenon that snowballs into a monster striking in the name of religion such as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). International terrorism feeds off local problems but increasingly has been synergistic with regional and global level confrontations making terror threat a globalized affair (Booth and Wheeler, 2008:271). This article will discuss the evolution of ISIS, its ideology, similarities to other terrorist groups like Al Qaeda and show how religion is reconstructed through new media in creating a religious identity among plenteous target audience. Specifically, the novel modernity that ISIS brings is a key element that should be closely examined in order to better understand the group.

Evolution of Islamic State

There are many speculations regarding the nature of ISIS because not enough is known about the group. Defining the group as Islamic State (IS), or the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), or ISIL (Islamic State in Iraq and Levant) as called by Barak Obama, or even Daesh (acronym for Al Dawla al-Islamyia fil Iraq wa’al Slam) as referred to by Francois Hollande, is therefore quite problematic. Several narratives surround its evolution, including some relating to ideology, Salafism, Wahabism, genealogy and linkage to Al Qaeda have been offered. However, according to Devji (2005), a common interest in establishing a virtuous Islamic order or ideas in common about the anti-Muslim policies is that the effects of jihad agglomerate diverse countries and peoples that are divorced from any prior history and that display little if any commonality. These forms of accounting are not helpful in understanding ISIS because it is a group that brings to the fore something that is simple and new. The group originated in 1999 as Jamaat al-Tawhid wal-Jihad, initially under Abu Musab al-Zarqawi with an oath to Al Qaeda, later called Al Qaeda in Iraq. After the death of Al Zarqawi in 2006, leadership was transferred to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi under whom it morphed into the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI). In April 2013 during the uprising against Bashar al-Assad, the group branded itself as the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham[1], Al Dawla al-Islamiya fi al-Iraq wa’al Sham and declared a caliphate, a state for all Muslims (Black, 2014).

Ideology

It is this so-called radical Islamic group that has seized large amounts of land in eastern Syria and Western Iraq, some of which include Raqqa, Qaim, Haditha, Ana, Falluja, Baiji, Mosul, and Sinjar; ISIS controls territory greater than many countries and now rivals Al Qaeda as the world’s most powerful jihadist group (Cambanis, 2014). Their goal is to establish a caliphate, a state ruled by a single political and religious leader according to Islamic law (Sharia), break the borders of Jordan and Lebanon and to free Palestine. The mode of operations of ISIS are quite austere and brutal including mass killings, abductions of members of religious and ethnic minorities, beheadings of soldiers and Western journalists. Religious minorities, particularly the Yazidis[2], have been specifically targeted by the group. Scholars like Devji argue that a group such as ISIS is more inclined to what he termed as “the politics of the surface”[3] due to its simplicity and superficiality. For example, the very attempt to broadcast forms of violence deliberately to the public can be seen as a sign of superficiality, or a preference for everything being on the surface, as self-evident. Common studies on terrorist groups are in line with the classical desire to constantly think about depth, interiority, an inner life and a transformation of this inner life as reasons for the creation of militants, terrorists and activists. According to Devji, understanding ISIS as a profound and subterranean group and attempting to find an astute ideology for their existence is difficult, given the superficiality of their actions. On the contrary, perhaps shallowness and superficiality are key to understanding the problem. A group like ISIS is greatly de-ideologised, which is evidenced by the display of apathy to its actions. It seems to draw its target audience easily through new media from all over the world without much difficulty in radicalizing in the first place. This form of radicalization is unprecedented in its manifestation; it does not require the more traditional training like that of Al Qaeda.

ISIS and Al Qaeda and Other Terrorist Groups- Differences

ISIS differs from other known terrorist groups such as Al Qaeda and the Taliban through its modes of operation. Al Qaeda is a global network that explicitly disavowed a formal identity as a state and never claimed a caliphate for itself. It is a global network that refused to be territorialised; it was more concerned with taking away the enemy. The reasoning process of Al Qaeda is grounded in a strategy of mirroring its enemy. A copycat type of reasoning is used by the group, i.e. “you kill ours so we kill yours.” One major aspect that the group believed in was suicide bombing (martyrdom) and operated entirely within the territory of its enemy, for example the 9/11 and 7/7 bombings. This further explains how Al Baghdadi’s vision differs from that of Osama Bin Laden mainly through its simplistic use of articulation of language as a way forward in applying military force in order to create an Islamic state that tears down the border between Syria and Iraq. As opposed to Al Qaeda, ISIS has territorialised itself; it has money, very good media outreach (perhaps better than other terrorist groups), geography and a caliphate. It has created a modern religious identity for itself, about a religious land full of love, purity and freedom. One major similarity with Al Qaeda is the use of the orange Guantanamo Bay prison style of clothing, which all their captured Western prisoners are forced to wear. However, occasionally it has adopted the mirroring language logic that Al Qaeda has used, with the killing of James Wright Foley, David Haines and Alan Henning for example. Yet, they do not make use of suicide bombings, which were prevailing strategies for Al Qaeda. The ISIS state is very different from the original Islamic States such as the Islamic Republic of Iran, because the Islamic States based their model on a kind of ethical vision of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) and his ruler ship in Madinah.

ISIS and the use of Religion and Social Media in shaping identity

Terrorism is often described as a process of radicalization, and radicalization is simply the process by which individuals are introduced to an overtly ideological message and belief system that encourages movement from moderate mainstream beliefs towards extreme views (Barlett and Miller, 2011). The latter can explain the existence of ISIS. The Internet’s unprecedented global reach and scope combined with the difficulty in monitoring and tracing communications makes the internet a prime tool for extremists and terrorists (Simon Wiesenthal Center and Snider Social Action, 2015). What is striking in this new context is that most of those recruited into ISIS are well educated and from middle upper class families, which shows that fanaticism knows no socio-economic level. They can join easily because the message is simple, aesthetic and straight forward. The difficulty here is that as a group so powerful, dangerous and disastrous, ISIS is at the same time very simple and superficial, which rapidly radicalises young boys and girls through the use of social media. In addition, the release of the ISIS Annual Report (al Naba[4]) serves as a motivational factor to these young souls as it depicts a group that is modern and organized with a free flow of information to potential targets. These annual reports showcase the group’s performances for potential and current donors because they contain all the operations carried out by the group such as assassinations, bombings and the liberation of prisoners. Because, ISIS is organised, modern and detailed, unlike Al Qaeda and the Taliban, it attracts numerous potential donors. It creates stimulation and intoxication to its target audience as has been evidenced by the ease and rapidness with which young girls and boys from Europe and other parts of the world run off to join ISIS. A report issued by the Simon Wiesenthal Centre (2013), found an alarmingly high incidence of digital hate and terror on Twitter specifically, used by terrorists to recruit, socialize with and embolden other potential terrorists. It can be argued that the spread of extremism online, especially social media can act as a surrogate offline social network.

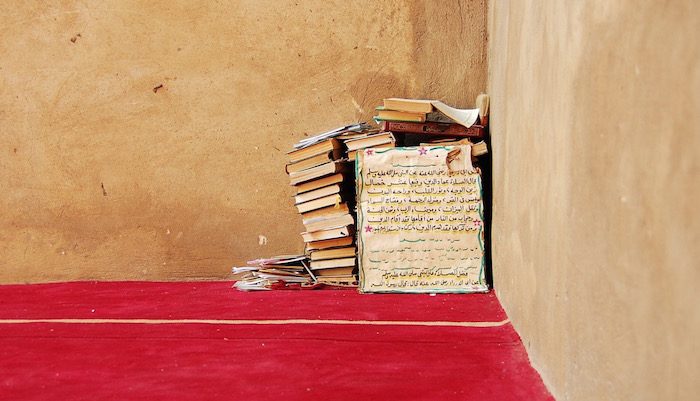

ISIS also uses the language of religion: ISIS’ actions are in the name of Allah and this is supported by verses of the Quran[5]. The message spread here is about a land of freedom, love, with clean shops, peace and where no guards are required. The beautiful peaceful image presented to the listener is capable of creating a sense of wishful identity and a sense of belonging to the group. Furthermore, Western teen recruits are used by ISIS in sending out messages of support and antipathy. This is a new propaganda element used to issue warnings and portray the West, especially the United States, as satanic to new followers. This was illustrated by the 17 year old Australian boy who acted as a spokesperson for the group.

A video, titled “Message from Dabiq”, showed three western jihadists, one from Britain, France and Germany daring the West to send in ground troops. All three made use of the sentence, “we are waiting for you.” The message relayed is customised and personalised specifically for the youth. The use of words and phrases like “we,” “us,” “your homeland,” “we are fighting for a cause,” “strengthen us and gives us purpose,” constructs a religious identity and a sense of belonging to the target audience. The language easily appeals simply by constructing the idea of a secure identity that is accepted and welcomed by a larger movement. The element of risk, danger and undisguised excitement serves to readily appeal to the youth, especially the love for youthful adventure and fun. Once recruited, they tend to view the group in a positive way with claims that ISIS is on the right track and that ISIS do not execute without evidence of wrong-doing[6]. This can be illustrated in a video posted by ISIS where John Cantlie, a captured British journalist, claims that there are two sides to every story, and accuses the Western media of twisting and manipulating stories for the public in the West. In the video, Cantlie directly accuses Britain and the United States of abandoning its captured citizens by refusing to negotiate their release like the other European countries. Of similar relevance is the video released by the group showing a British jihadist motivating others to join the Islamic state. This is a direct message encouraging people in the West to join ISIS, by sending out information about a peaceful land to potential recruits. The level of professionalism and quality of technology used by the group effectively portray a twenty first century, modern jihad movement with high sales marketing and spin which attempts to engage one billion Muslims all over the world. Hence, tweets and videos released through social media make recruitment easy for ISIS.

The modernity and simple sophistication deployed by ISIS help shape and reconstruct the unique religious identities of the target audience. They achieve this through the creation of a sense of belonging by simply calling out to their target audience to come home to a land of peace, love and join their brothers from other parts of the world for the cause of no other but Allah (God). The impact achieved by ISIS through the use of new media serves to escalate the conflicts between Western countries and ISIS. The group is recruiting more young boys and girls from Western countries, which in the end, produces a culture of hate and enmity between these youths and their home countries.

Notes

[1] Historic name for Syria.

[2] Yazidis are Kurdish ethno-religious community religion is linked to Zoroastrianism, Jewish, Nestorian Christian, Islamic and Mesopotamian elements.

[3] The notion of “the politics of the surface” was communicated in a seminar conducted by Devji.

[4] Arabic word for “the news”. A corporate style annual report released by ISIS on their military campaigns since 2012. So far three reports have been published in 2012, 2013, and 2014.

[5] See for example the video posted by Journeyman TV (2010).

[6] See for example the “Young Ex-ISIS hostage: They are right” video, where Merwan Hussein from Kobane speaks in favour of ISIS.

References

Bartlett, J. & Miller, C. (2011) “The Edge of Violence: Towards Telling the Difference Between Violent and Non-Violent Radicalization” Terrorism and Political Violence, 24(1), pp. 1-21.

Black, I. (2014) “The Islamic State: is it Isis, Isil – or possibly Daesh” [online] available at: http://gu.com/p/4xm5b/sbl [Accessed 19 May 2015]

Booth, K., & Wheeler N.J. (2008) The Security Dilemma: Fear, Cooperation and Trust in World Politics. Palgrave Macmillan

Brown, M. (2003) “Introduction: Security Challenges in the Twentieth Century” in Brown, M. (ed) Grave New World: Security Challenges in the 21st Century, Washington DC: Georgetown University Press

Bush, G. H.W. (11/09/1990) “Address Before a Joint Session of Congress” [online]. Transcript available: http://millercenter.org/president/speeches/speech-3425 [Accessed 23 April 2015]

Cambanis, T., (2014) “Sunni Fighters Gain as they Battle Two Governments, and other Rebels” New York Times [online] available: http://nyti.ms/1pHZgvx [Accessed 19 May 2015]

Devji, F., (2005) Landscapes of the Jihad: Militancy, Morality, Modernity. Cornell University Press Ithaca, New York.

ISIS (16/10/2014) “Message from Daqib” [online] available at: http://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=message+from+dabiq+video+youtube&FORM=VIRE3#view=detail&mid=ABAECBF7F3847C21F8E9ABAECBF7F3847C21F8E9 [Accessed 19 May 2015]

ISIS (6/10/2014) “Young Ex-ISIS hostage: ‘They are Right’” [online] available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ajh2HxBngg0 [Accessed 19 May 2015]

Journeyman TV (2014) “Inside ISIS and the Iraq Caliphate: Social networking for Islamist Extremists” [online], available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yvE-ZYTziTU [Accessed 23 April 2015]

Murphy, C.N. and Weiss, T.G (2012) “International Peace and Security at a Multilateral Moment: What We Seem to Know and What We Don’t, and Why” in Croft, S. and Terriff T. (eds) Critical Reflections on Security and Change, Abingdon: Routledge

Reynalds, J., (2013) “Simon Wiesenthal Canter’s 2013 Digital Terror and Hate Report: Instances of Online Hate up by 30 percent” [online] available at: http://www.christianplusfi.com/news/simon-wiesenthal-centers-2013-digital-terror-and-hate-report-instances-of-online-hate-up-30-percent/#.VVpSJv1Usus.gmail [Accessed 15 May 2015]

Simon Wiesenthal Center and Snider Social Action Institute (2013) ‘Online Terror and Hate: The First Decade” [online], available at: http://www.wiesenthal.com/atf/cf/%7BDFD2AAC1-2ADE-428A-9263-35234229D8D8%7D/IREPORT.PDF [Accessed 23 April 2015]

The Guardian UK (2014), “ISIS declare caliphate in Iraq and Syria” [online] available at: www.theguardian.com/world/middle-east-live/2014/jun/30/isis-declares-caliphate-in-iraq-and-syria-live-updates [Accessed 19 May 2015]

The World Bank (2011) “World Development Report 2011”. Conflict, Security and Development. [online] available at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWDRS/Resources/WDR2011_Full_Text.pdf [Accessed 19 May 2015]

Watson, L. (2014) “Jihadi Terror Group Plc: ISIS zealots log assassinations, suicide missions and bombings in annual report for financial backers” [online], available: www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2661007 [Accessed 19 May 2015]

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- 5 Reasons Why the West Got Islamist Terrorism Wrong

- Unmasking ‘Religious’ Conflicts and Religious Radicalisation in the Middle East

- Realism, Post-Realism and ISIS

- Is the Conflict in Anglophone Cameroon an Ethnonational Conflict?

- United Moderate Religion vs. Secular and Religious Extremes?

- Islamic State Men and Women Must be Treated the Same