Can theories of International Negotiations Explain the Failure of the Iranian Nuclear Negotiations in November 2014?

Introduction

Research Motivation and Outline

Theories regarding international negotiations are abstract at best and unrealistic and over-simplistic at worst. Having spent many a lecture trying to wrap my head around game theory and how it proposes to solve complex issues of conflict between people, let alone nations, I had developed the belief that those theories could hardly offer any assistance when trying to understand real-life scenarios and that if one were to apply different theories they would likely be contradicting. Therefore, I decided to write this term paper on precisely that: the question of whether those abstract models could believably and consistently explain the outcome of a conflict which really took, and still takes, place. The conflict which I chose for the case study is the debate surrounding the Iranian nuclear ambitions. Talks surrounding nuclear proliferation are held on high policy maker levels and inspire great involvement of all the parties involved, as the significant loss or the gain of national security is at stake. The fundamentally conflicting interests of the parties allow for extreme best and worst outcome scenarios and can thereby be more easily simplified to fit the framework of a theoretical model.

I began my research by reading up on the existing theories of international negotiations, in order to make up my mind which ones I would try to apply to the Iranian Nuclear Talks. Soon I realised that there are far more models available than one could hope to squeeze into a single essay, so I decided to first have a glance at theories of bilateral bargaining, seeing that those are the basis for many more theories. Next I would attempt to formulate a game theoretic model of the Iranian Nuclear Negotiations, as this theory claims to be capable of explaining actors’ strategies and decision-making based on mathematics. I was curious to see how such an abstract approach would do justice to an issue that is positively impossible to quantify. Then I decided to move away from these most traditional approaches to examine how less general analyses of negotiations could explain the failure of the Iranian Nuclear Negotiations in 2014. The aspects I chose to bring into this term paper are power asymmetries, individual negotiation styles, international mediation, and information. I chose power asymmetries as the first aspect as it seemed quite clear to me that the negotiations between the US and Iran were obviously marked by the power imbalance caused by the strong position of the US. Individual Negotiation styles seem to be of small importance when looking at the negotiations between such internally fractured actors as states. However, I was interested in learning how negotiators themselves assess their influence. My choice to bring mediation into the essay was based on a similar reason, however I wanted to examine how much power a mediator can have when trying to interfere in talks between such powerful actors. Information was one aspect that is being referred to in almost all other theories on international negotiations, therefore I decided it was an important influence on the negotiations.

After giving an overview over the theories relating to those aspects in the second section, I will turn to the application of the models to the Iranian Nuclear Negotiations in the third section. I will apply the traditional theories by recreating their models as graphs featuring the key facts of the negotiations and examine whether or not those models speak in favour or against a negotiated solution. Then I will move on to the more specific aspects of bargaining, by examining which power asymmetries exist between Iran and the US and how they should theoretically affect the negotiations, by categorising the individual negotiation styles of the countries’ representatives and which outcome their combination should yield, by analysing the mediation approach used in the Iranian Nuclear Issue and how that is supposed to affect the talks, and lastly, by assessing how efficiently information is exchanged between the parties and whether that is beneficial or damaging for the negotiations. Lastly, after establishing whether or not the different theories explain the failure of the talks, I will draw my conclusion in the last section.

Theoretical Framework

Models of Bilateral Bargaining

This section aims to give an overview on the theory of bilateral bargaining by explaining how to map an international conflict as a simplified model. Understanding the framework one can use to create such a model will enable us to create a game theoretic description of a conflict, which can help in “describ[ing] a conflict in terms of general theory [and] of some general principles covering human action”, in “gain[ing] insights into [the] behaviour of participants in a conflict” and in “advis[ing] those who are involved in a concrete conflict” (Avenhaus, 2009, p. 87). The first two of those benefits will make it possible to identifying the reasons for the failure of a negotiation and the latter is crucial to give a qualified recommendation on how the repetition of such a failure might be avoided.

Bargaining can be understood as the negotiation between two or more nations and will occur both in times of peace for the building and strengthening of relations, and in times of conflict for the solving of problems. A negotiation involves two strategies: coercion and accommodation (Snyder & Diesing, 1977, p. 4). It is assumed that parties of negotiations can make concessions (accommodative aspect), but also force an adversary into making concessions (coercive aspect) in order to reach a desirable outcome (ibid., pp. 22). Those two negotiation behaviours leave an actor with a choice: to accept or to reject the offer made by the other party. When presented with an offer of concession, the actor can risk to reach an agreement for the possibility to receive an even better offer; while when presented with a coercive proposal, the actor may hope that through not accepting the coercive measure will be withdrawn, but therefore risks that it will be carried out (ibid. 23).

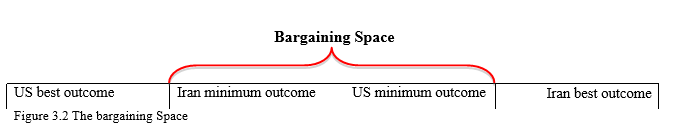

To set up a simple model of bargaining, one can consider that two actors are in a dispute over the distribution of a good (which can be physical, such as tariffs, or abstract, such as security). Both want said good or a certain amount of it for themselves, and thereby have to exchange bids proposing a certain distribution until an agreement is reached or until the negotiation is abandoned (ibid., p. 34). Such bids move along the “conflict line” (ibid, p. 35), and are limited by the minimum desirable outcome of each party, where no agreement is more attractive to one party than a settlement. Any proposals that fall into the space between minimal expectations may result in agreement. That space is called the “bargaining space” (ibid.) The larger the bargaining space (i.e. the closer each actor’s minimal desirable outcome falls to the optimal outcome of the other actor), the easier it is to reach an agreeable distribution of the good. Equally, if at least one negotiator considers even the slightest gain for the other negotiator to be his own worst outcome, reaching an agreement is near impossible. Acts of concession or coercion can change the conflict line and impact the desired outcomes. If party A offers to make a concession in an issue outside of the current conflict, party B’s minimal desired outcome might decrease. Also threats will influence those boundaries: If A threatens a measure in case of non-agreement, B’s willingness to cease negotiations will decrease which will elevate his minimum desirable outcome.

Since not one single player can determine the outcome, as the interests and decisions of the actors are interdependent, such bargaining can be constructed as a game (Brams, 2003, p. xxii). There are two sorts of games: zero-sum games and non-zero-sum games. The former applies to situations where an outcome will benefit one player as much as it harms the other, thereby resulting in a total change of zero (it is to be noted, that, according to Snyder and Diesing, this “is not empirically to be found in international politics” (1977, p. 38)). The latter assumes that in some situations, total value can differentiate from zero, either by making both players better off, or by making one player worse off than the other one gained in relation to that loss.

In every game, each player has to follow a strategy and pursue it with corresponding tactics (Snyder & Diesing, 1977, p.38). One can identify five strategies which can be ranged according to their willingness for accommodation or coercion: the first is the “extreme accommodative strategy” (ibid.), which aims to find the most useful concession to make in order to reach agreement, the second is a “mixed strategy” (ibid.), which will make moderate concessions without giving in on vital issues, the third is a “firm strategy” (ibid.), which strictly denies making concessions, the fourth is an “escalating strategy” (ibid.), which accepts the risk of war in order to make the adversary yield and the fifth is an “attack strategy” (ibid.), which only participates in negotiations in order to gain time to prepare an overt attack (ibid.).

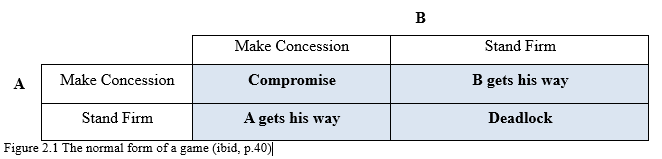

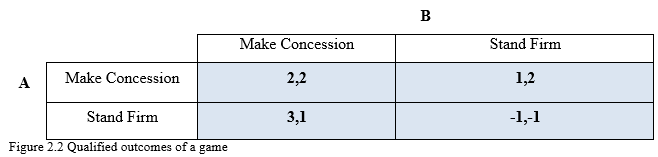

There are two most common ways of representing a game: the normal form and the extensive form. The normal form constructs a matrix which represents the strategies and the expected outcomes for each player.

In figure 2.1 one can see the different outcomes that each combination of strategies will result in. To make those outcomes quantifiable, one can assign values to them as I did in figure 2.2. A compromise for example might make both players better off, giving them a (2/2) outcome. If A gets his way, this might give the players a (3/1) outcome, which means that this is a better outcome for A than for B. If B gets his way, the outcome might be (1/2), which means that although it is a more favourable outcome for B, the benefit for that player is not as high as it would be the other way around. In case of a deadlock, it is possible that both parties face a negative outcome of (-1/-1).

The extensive form of a game is useful if the decisions of the players are not taken simultaneously but chronologically. As in most bargaining situations the players exchange a large amount of bids, one would have to construct this form for each stage of negotiation, which can be exceedingly difficult, seeing that one has to assign values for each bid and also make projections of how the players react to every single bid. This is probably an approach too detailed to be practically useful.

Constructing such models is crucial to finding equilibrium solutions which can be reached. In order to project which strategy a player will chose, game theory assumes that players are rational and therefore chose the strategy most likely to give them the best outcome (Mascheler, Solan & Zamir, 2013, p. 86). Said outcome can be found by eliminating dominated strategies (or strategies which result in a worse payoff). Strategies can be strictly dominant if they give the player the highest payoff regardless of which strategy the other player chooses; or weakly dominant, if they always result in at least the same payoff for all strategies of the adversary and in a higher payoff for at least one of them (ibid., p. 90). For the game in figure 2.2 that means that player B will eliminate the strategy “Stand Firm”, as “Make Concession” is weakly dominant. Since player A knows that player B is rational (ibid, p. 87), he will assume player B to use the strategy “Make Concession”. Therefore, he will pick the strategy “Stand Firm”, as it now strictly dominates the other strategy. This means that the rational equilibrium outcome for this game is “Stand Firm”/”Make Concession”. Another solution concept is the Nash equilibrium, which can be found where no player can improve his outcome given that the other player does not change his strategy. Such an equilibrium exhibits stability through a “self-fulfilling agreement” (ibid., p. 101), as no player will be willing to change their strategy and thereby adheres to the agreed outcome. For the example above the Nash equilibrium lies at “Make concession”/”Stand Firm”, as it is the only outcome where neither player can improve his outcome by changing, given that the other player keeps his strategy.

While the models described above can assist us in understanding crisis bargaining, they meet several limitations: bilateral negotiations are seldom conducted by unitary rational actors, information is rarely universally available and correctly processed, and the factor of time pressure does not feature in traditional bargaining models (Snyder & Diesing, 1977, p.181).

Aspects of International Negotiations and their Impact

In this section I will move from the traditional bargaining models presented earlier in order to examine some other aspects which influence negotiations and which can only indirectly be reflected in game theoretic models. Those influences which I chose to investigate are power relations, individual negotiation styles, mediation and information. Of course, one could also examine the impacts that the internal organisation of a state has on its bargaining behaviour, the possible effects of the international political climate and the changing of a negotiation’s course due to time pressure.

The first aspect of negotiations that has an impact on bargaining is power asymmetry. Such imbalances reflect the interdependence of states, and how usually, one is more dependent than the other, and the leverage which stems from such dependence (Wolfe & McGinn, 2005, p. 1). In order to examine the influence power and power asymmetries have on negotiations, one needs to move away from the classical definition of power, that lies in the ability to make someone do something even against their will (Dahl, 1957), as this definition focuses on the outcome of an interaction (or negotiation) and does not account for the sources of power. Also just focusing on the resources of power is not sufficient, as this does not imply that they will actually be put to use. According to Habeeb, “power thus lies between its source (resources) and its result (outcomes)” (1988, p. 14). One might therefore choose to use the definition that “power is the way in which actor A uses its resources in a process with actor B so as to bring about changes that cause preferred outcomes in its relationship with B” (Odell in ibid., p.15). Habeeb identifies three dimensions of a nation’s power: aggregate structural power (the resources a country has), issue power (resources which relate to the specific issue under negotiation) and tactical power which describes the ability to use resources in order to reach a goal (ibid., p.129). Each of those dimensions can have a different impact on bilateral negotiations, however it seems that the most important one is issue power, as the negotiation process is essentially aimed at shifting this power relation (ibid., p. 130). This dimension is influenced by the three components alternatives, commitment and control; where alternatives describes the dependence of an actor on one specific outcome (the more alternatives he has, the less dependent he is), commitment refers to the value an actor places on his desired outcome (if the desire stems from inherent values rather than needs, this is a source of power) and control relates to the ability of an actor to reach its desired outcome unilaterally outside of negotiations (ibid., p.20ff). In the limited frame of this paper, it may be best to focus on this power dimension as it has the largest impact on the outcome of negotiations.

Another factor which will influence the process of a negotiation is the individual negotiator. Different styles of negotiation will cause the bargaining process to develop in different ways and result in different outcomes. Two styles that one can identify are cooperative/problem-solving and competitive/adversarial negotiators (Craver, 2003). The former share a more forthcoming attitude to their negotiation partners, seek to maximise the benefit of both sides, are interested in disclosing information, understanding the other side’s point of view and are willing to make concessions (ibid., p. 1). When two cooperative parties negotiate, both sides tend to follow this approach (ibid., p. 4). Competitive negotiators stand in stark contrast. They assume an adversarial attitude to their partner, only wish to maximise their own benefit, withhold information, focus on their own point of view and are unyielding in their position (ibid., p. 1). When two such negotiators face each other in a bargaining situation, this behaviour will lead to a lack of information on both sides, while in a negotiation between the two different styles the cooperative partner’s willingness to share information will lead to an advantage for the competitive negotiator (ibid., p. 4). Three assumptions can be made about the outcomes of negotiations depending on the different styles: agreements which strongly favour one side of the negotiation are usually obtained by competitive negotiators, but also the abandonment of negotiations is often caused by competitive negotiators due to their unaccommodative nature; lastly, cooperative negotiators tend to realise their goal of maximising joint benefit of negotiations (ibid., pp. 3f). However, in international negotiations between states it may be doubtful how large the impact of bargaining styles really is. After all, the diplomats in charge of speaking on behalf of their country have to follow the orders given by their superiors. Only if the negotiations take place at the very highest level between head of states, this might change. Still, the only ones which enjoy some personal decision-making power are heads of totalitarian systems, who can more easily push a personal agenda than the head of a democratic state who will have to justify his actions to different scrutinising institutions, the (more or less) unbiased media and the general public.

Mediation is “a form of peacemaking in which an outsider to a dispute intervenes on his own or accepts the invitation of disputing parties to assist them in reaching agreement” (Douglas in Bercovitch 2011, p. 67). Bercovitch lists the following characteristics of mediation: it is a branch of “peaceful conflict management”, it requires a third party to step into a conflict between several conflicting states, it is a “non-coercive, non-violent and ultimately non-binding” approach to conflict resolution, the mediator has the aim of impacting the conflict positively, but cannot be considered unbiased and lastly, all parties participate in the mediation process on a voluntary basis (Bercovitch, 2011, p. 70). Mediation becomes an option for the resolution of a conflict when the parties’ efforts to settle the conflict have proven fruitless, the conflict remains and both parties are willing to cooperate to avoid further damages (ibid., p. 73). The motives for individuals to step up as mediator can stem both from the desire to make a positive impact by ending or amending a crisis, but also from self-serving reasons such as the search for personal proliferation (ibid.); for persons acting on behalf of an institution or state an additional motivation is the fulfillment of a prescribed duty (ibid., p. 74). The conflict parties’ motivation for seeking mediation are the possibility of a conflict settlement, the hope that the mediator will influence the other side in a beneficial manner, the public expression of commitment to a peaceful solution, the option to lay blame on the mediator should negotiations fail, and the service of supervising and safeguarding a possible agreement (ibid.). When called upon, a mediator can use three different strategies that offer different tactics. The first is a facilitative-communicative strategy, which relies on improving the communications between the negotiation partners and aiding in mutual understanding. The second is a formulative strategy, which aims at establishing rules for the negotiation and balancing out power asymmetries. The third is a directive strategy, which actively manipulates the parties into reaching an agreement (ibid., p. 77). The choice of strategy depends on the conflict under discussion and will be adapted as the conflict develops (ibid.).

Evaluating the success of mediation can be achieved in two ways. The first is the subjective criteria, which focuses on the perception the participants have of the mediation effort. If the conflict parties share the impression that it was successful in positively amending or even dissolving the conflict, the mediation meets the subjective criteria of success, although such perceptions can be hard to quantify (ibid., pp. 85f). The second way of assessing success is the objective criteria which examines the hard facts surrounding the mediation, such as “permanence of the agreement, the speed with which it was achieved, the reduction in the level of hostilities between the disputants, [and] the number of issues on which agreement was achieved” (ibid., p. 86). To come back to the issue of power asymmetry, it is notable that while most attempts to peacefully settle asymmetric conflicts will not be attempted or are expected to fail, mediation is often called upon in such situations (Quinn et al., 2009, p. 188). Quinn et al. even go so far as to formulate the hypotheses that “ mediated asymmetric crises are more are more likely to end in formal agreement than are mediated symmetric crises” and that “mediated asymmetric crises are more likely to result in long-term, post-crisis tension reductions than are mediated symmetric crises” (ibid., p. 193). However, this likelihood of success also depends on the strategy pursued by the mediator and “will be highest when mediation is manipulative, lower when mediation is formulative and lowest when mediation is facilitative” (ibid., p. 195).

The last aspect which influences negotiations that I will turn to is information sharing. There exists a dilemma regarding information sharing in negotiations: if each participant provides the other side with free and accurate information, this increases the chance to obtain a more beneficial outcome for both parties, but if only one side shares information, it may be used to his disadvantage by the other side, who may either deny to provide information or misinform his adversary (Murninghan et al., 1999, p.313). If negotiators are unclear about their partner’s preferences and intentions, it is difficult to establish what one would actually lose in case of concessions, and how far concessions need to go in order to be beneficial for the finding of an agreement. As each side is aware that revealing information can be used against them, neither will be able to trust the revelations of the other, resulting in a deadlock and the loss of useful information.

The Iranian Nuclear Negotiations

The Iranian Nuclear Issue

Iran’s history with nuclear energy began in November 1967 with its first operating research reactor which was supplied by the US (Arms Control Association, 2014). During the 1970’s Iran ratified the Non-proliferation Treaty and heavily promoted peaceful usage of nuclear energy through the Atomic Energy Organisation of Iran (AEIO), before the revolution in 1979 and the succeeding break with the US halt those plans (ibid.). The 1980’s saw the introduction of severe US sanctions against Iran as a sponsor of terrorism and the Iranian acquisition of the technical plans for a centrifuge used for uranium enrichment from the Abdul Qadeer Khan network (ibid.). In the 1990’s the US declared an embargo against Iran aimed at preventing it from acquiring advanced conventional weapons and prohibited heavy investments of US firms in Iran’s energy sector. Still, in cooperation with Argentina, Iran built the Tehran Research Reactor (ibid.). In 2002 the political branch of the terrorist group Mujahideen-e Khalq revealed the construction of nuclear sites near Natanz and Arak by Iran (ibid.). After the proposition made by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in 2003, Iran agreed to halt all enrichment activities and allow local investigations through IAEA representatives. The following years were marked by a back and forth between Iran and the UNSC, which included Iran agreeing to comply with resolutions, revealing that it broke them and the UNSC imposing further sanctions (ibid.). In 2009 the US announced it was planning to fully partake in P5+1 (UNSC permanent members and Germany) talks with Iran and convinced Iran to agree on another deal to halt enrichment. Iran broke the deal in 2010 and declared that it has enriched uranium to 20 percent, the UN, and the US and the EU impose further sanctions (ibid.).

In 2012 further talks failed, but during that year several negotiations took place in Istanbul, Baghdad and Moscow, which lead Israel to declare a “red-line” of attack on Iran as soon as it amassed enough 20 percent uranium for the construction of a nuclear bomb; during all this, Iran continues to advance its nuclear programme and to enrich uranium to 20 percent (ibid.). In 2013 it became clear that the 2012 negotiations failed (ibid.). After the election of Hassan Rouhani, new talks with the P5+1 were undertaken in Geneva and were said to follow a very positive development (ibid.). In November the Joint Plan for Action was signed and prescribed several measures taken by both sides over a six months period (ibid.). Early in 2014, the implementation of the framework began and is reported to be adhered to by IAEA observers, while the P5+1 and Iran kept searching for an agreement of how to proceed after the six months (ibid.). In August it became clear that Iran had failed to meet certain crucial deadlines and to provide information on its plans for possible military usage of uranium (ibid.). The parties set a deadline for their talks for November 24, and entered a round of intense negotiations (ibid.). However, on that day the only agreement which was been reached was that negotiations shall continue for at least seven months; no new goals for the parties have been set and no new action plans signed (ibid.).

The reactions to that outcome in Iran were disappointment and exhaustion in the face of ongoing sanctions (The Guardian, 2014), while most American politicians agree that an extension of the talks is preferable to a negative outcome, but consider further sanctions a possibility (Sanger & Gordon, 2014). This can by no accounts be considered a complete tale of Iran’s nuclear programme, as it is unclear whether Iran has concealed any more nuclear sites or developments which are not yet known to the P5+1 (Lodgaard, 2007, p. 99).

Explaining the Failure of the Iranian Nuclear Negotiations

To analyse the Iranian Nuclear Negotiations, I will proceed by first mapping the bargaining situation, secondly by creating a game theoretic representation, and then by investigating how the aspects of power relations, individual negotiation styles, mediation and information affect the negotiations.

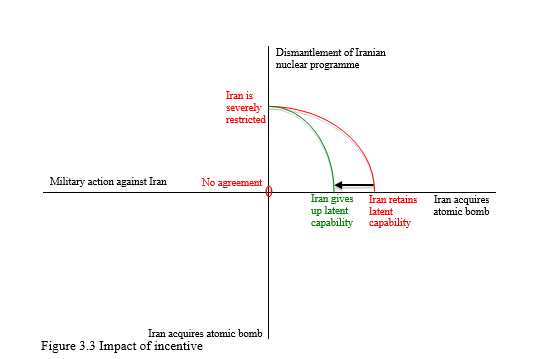

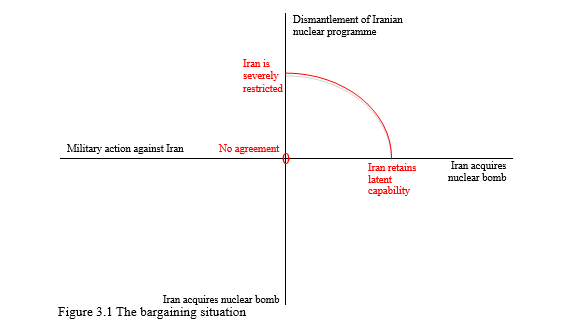

To create a representation of the bargaining situation between the two sides of the Iranian Nuclear Negotiations (I will assume the US to be the driving force of the conflict management as it was the first country to put in place sanctions in response to Iran’s nuclear policies and is still prominently represented at the negotiation table), one has to define the cornerstones of the conflict by answering the following question: Which are the outcomes with the highest and lowest utility for the US and for Iran respectively? As it is assumed, although denied by Iran, that Iran seeks to establish nuclear weapons capacities for itself, it is arguable that the worst outcome for the US is the acquisition of a nuclear bomb by Iran (Sebenius & Singh, 2012, p. 13). Such an assumption is based on the presence of the reactor in Arak (the same kind aided India and Israel in their quests for nuclear proliferation), the question why a country with access to such abundant sources of oil and gas needs nuclear energy, and the efforts to conceal the nuclear programme from the rest of the world (Lodgaard, 2007, p. 100). The exact opposite of this outcome, the dismantlement of the Iranian nuclear programme is the US’s preferred outcome, as it reduces the threat of an Iranian nuclear bomb the most. For Iran, the best outcome is obviously that which constitutes the worst outcome for the US: the ability to develop its nuclear programme enough to reach the goal of nuclear weapons capability. However, the possibility of a military response to such an achievement by the US is high, and this outcome would likely be devastating for Iran due to the US’s superior military capabilities (ibid., p. 15). Having thus established the four cornerstones of the bargaining situation, we can draft the following graph:

Here, the X axis shows us the utility any outcome will have for Iran and the Y axis shows such utility for the US. The best and worst outcomes can be found at the maximal and minimal points of the axes respectively. At the point 0 no agreement is reached and any outcome located to the South West will be negative for both parties. The red line represents the conflict line, which indicates the relation between the minimal desired outcomes. To reach a deal, any bids must fall to the North East of this line (Snyder & Diesing, 1977, p. 35). While there are degrees to which the US might want to restrict Iran’s ability to produce a nuclear weapon (Sebenius & Singh, 2012, p. 23), it can generally be said that the minimal desirable outcome for the US is a severe inhibition of Iran’s nuclear abilities. For Iran, it is desirable to keep a “foot in the door” to nuclear proliferation, which depends on the degree of restriction on nuclear activities and on the sanctions that the US imposes (ibid., 25). Thus, in order to reach an agreement, the US and Iran need to find a deal which satisfies both those conditions. The range of deals which can be considered is represented in the graph below:

As it can be assumed that the US’s position does not plan to allow Iran latent capabilities, the bargaining space is limited to zero (ibid, p. 26). In order to widen the bargaining space, either the US or Iran can make use of concessional or coercive means, i.e. incentives or sanctions. The following graph illustrates the change of the conflict line after the preposition of an incentive (e.g. the reduction of sanctions) by the US:

The green line represents the new conflict line, which increases the amount of possible deals to the North East by decreasing Iran’s minimum desirable outcome while that of the US remains the same. The black arrow equals the expected benefit which accumulates to Iran from the incentive. This indicates that when looking at the negotiations through the lens of models of bilateral bargaining, it might be most effective to work with measures of coercion and incentives to widen the array of viable deal options (ibid., p. 48).

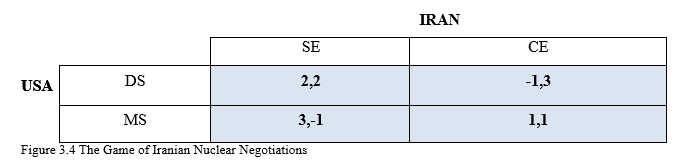

Another way of drafting a bargaining situation is through a game theoretic payoff matrix. For this end, one has to first decide on which strategies one can imagine either party to pursue. As Iran’s optimal outcome is the construction of a nuclear arsenal, its strategies will be to either continue to enrich uranium and to pursue their goal of nuclear proliferation or to cease such activities and to comply with international restrictions in order to use nuclear energy only for peaceful means. For the US, as we have observed, sanctions as a coercive means may be a viable strategy to keep Iran from reaching nuclear weapons capabilities. Therefore, its two strategies are to either use coercive means such as sanctions against Iran, or to drop those sanctions and to accept Iran’s approach to uranium enrichment. Such a game might look as follows:

Strategies: USA: DS: drop sanctions, MS: maintain sanctions;

IRAN: SE: stop enrichment, CE: continue enrichment

The different combinations of strategies represent different situations and yield different outcomes for the players. The first outcome which is the result of strategy set DS,SE leads to the highest joint benefit for most players. It represents the situation in which Iran and the US find an agreeable deal and adhere to it. Iran stops the enrichment of uranium, retains the option to use it for peaceful means and also experiences the benefit from abandoned sanctions. While giving an exact value for the resulting benefit is impossible, but the end of the oil boycott and the restrictions for trade with Iranian banks is likely to spur a very effective means to boost Iran’s economy and to halt inflation (ibid., 37). For the US, such an outcome is also beneficial, as it can be considered a win for American diplomacy and seen as a manifestation of global American authority. In addition, a successful deal may greatly improve US-Iranian relations, which have suffered greatly during the past decades of severed relations (ibid., p.26). Such an improvement may grant the US the option to further influence Iranian policies for its and its allies’ advantage.

However, despite this generally beneficial outcome, the results for DS,CE and for MS,SE are even better for either one of the parties. If the strategies DS and CE are followed, this could be noted as an incredible win for Iran, as it indicates that the US dropped all demands and allowed Iran free reign in regard to nuclear energy. In the absence of restrictions and international supervision and with all sanctions gone, Iran’s goal to achieve nuclear weapons capability is within short reach. Therefore, in addition to the benefits enjoyed in the first case, Iran also greatly improves its global standing and security. Obviously, such an outcome would be devastating for the US, as it means a huge loss of global status as guardian of stability (ibid., p. 15), an increasing likelihood for more powerful adversaries in the Middle East (ibid., p. 16) and the complete loss of influence on Iran’s politics. Therefore, it is entirely unlikely that such an outcome will see the light of day.

Also the third outcome (MS,SE) is not much more probable. This outcome is very positive for the US, as a deal that forces Iran to stop its enrichment activities but allows the US to maintain the restrictions and sanctions on Iran severely limits Iran’s ability to acquire an atomic bomb, but gives the US the option to control Iran’s policies in the future, possibly for the pursuit of different issues which the US and Iran differ on. In addition, such a deal is another manifestation of American authority, as it shows the ability of the US to coerce another country into agreeing to a very unbeneficial deal. Iran is very unlikely to accept a proposition which removes it furthest from giving up any options to pursue nuclear proliferation. Why would it comply with an agreement without receiving any benefits, but lose international standing?

The most likely outcome can be found when the parties follow the strategies MS,CE. And indeed, this is the current situation. When the US maintains its sanctions against Iran and Iran is unwilling to reduce its nuclear enrichment, the benefits are low, although they are still higher than the worst case scenarios. Maintaining sanctions gives the US the possibility to hinder Iran’s progress in the field of nuclear development, but is unable to stop it. Similarly, Iran is able to proceed with its plans for proliferation, but is slowed down due to sanctions (O’Sullivan, 2012).

So what equilibrium outcomes can one identify with the help of game theory? While it is obvious that the result with the largest joint benefit is the one which entails concessions for both parties, according to game theory it is unlikely that this option will materialise. The reason for this is firstly that rational playing will eliminate this option, but also the possibility, that in the face of damaged bilateral relations, the level of mistrust is high. If Iran chooses to stop enrichment trusting the US to drop the sanctions, it is possible that the US will deflect and break the contract by instead keeping sanctions in place. Of course, if that happens, Iran will be quick to drop its part of the bargain and resume its uranium enrichment activities. The other way around is also not trustworthy for the US, as Iran might break its word by resorting to clandestine nuclear proliferation. Instead, the most likely outcome is the stalemate created in the fourth scenario. If both parties eliminate the dominated strategies, this is the result of their remaining strategy. The Nash equilibrium for this game can also be found in that outcome. Neither the US nor Iran can improve their outcome, so long as the other sticks to his strategy. If the US changed to DS, it will lose benefits, and the same is true if Iran changes to SE. Therefore, the stalemate enforces itself according to game theory.

This result reinforces the result deducted earlier, that at this point, according to traditional models of bargaining, there is no solution to the Iranian Nuclear Negotiations.

Moving on to the examination of power asymmetries between the US and Iran, one thing becomes clear at first glance: Speaking in terms of Aggregate Structural Power, the US has the upper hand. Looking at indicators such as size and location of territory, population, raw materials, economic structure, technological development and financial strength, one realises that the US, being the fourth largest country in the world having 320 million inhabitants, rich and diverse resources and the most diversified economy worldwide with the highest GNP, highly developed technologies and a strong financial market far outmatches Iran (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2015). Iran’s territory is a third of that of the US and located in a war-ridden region, the population of 77 million, the high reliance on natural gas and oil (which is however abundant), and the hindered development of the economy due to international isolation caused by both autarkic Iranian politicians and sanctions can not be made up for by the only factor which gives Iran an advantage: the nature of its borders which are mostly constituted by high, not easily crossed mountain ranges (ibid., 2014).

Turning to Issue-Specific Power, the approach is less straightforward. To assess how the factors of alternatives, commitment and control are spread among the two nations, one has to do a bit of guesswork, as there is no quantifiable data available. Alternatives are defined as “each actor’s ability to gain its preferred outcomes from a relationship other than that with the opposing actor” (Habeeb, 1988, p. 21). For the US, such an alternative does not exist. Its preferred outcome of preventing Iran from acquiring an atomic bomb depends on Iran’s ability to make said achievement. Therefore, the US is entirely dependent on reaching an outcome in accordance with Iran and is thusly more dependent on successful negotiations. This gives Iran more power, as Iran does indeed have alternatives to reaching its preferred outcome of nuclear proliferation: As its nuclear programme has before been supported by terrorist networks, North Korea and Bangladesh, Iran has the option to turn to these actors for support for its programme.

The existence of such an asymmetry in this factor of power is another reason for the ongoing stalemate in US-Iranian negotiations: “[Iran] may be able to achieve much of its preferred outcome by not negotiating, or by stalling in the negotiations” (ibid.). The second determinant of Issue-Specific Power, commitment, might be the hardest to assess. For the US, preventing the nuclear proliferation of Iran is a top priority. Its fears in case of a possible failure include the loss of Israel’s nuclear dominance in the Middle East (and thereby a loss of American influence in the region), the chance of a nuclear first strike against one of the US’s allies, an increased support for terrorism by Iran (and maybe even the transfer of nuclear weapons to terrorist networks) and the growing nuclear ambitions of further countries in that region (Waltz, 2012). Those are grave consequences and even without consideration for the loss of international credibility and standing that the US would suffer, it is clear that the US has a very high commitment to achieving its goal. Iran’s motivations for acquiring nuclear weapons capability is based both on external and internal needs: An atomic bomb provides both defensive and offensive capabilities and thus increases national security greatly; also, the tangible achievement presented by acquiring the bomb will help Iran’s government to legitimise its rule and to justify the past suffering from economic sanctions (Sherrill, 2012). In addition to that, the ability to defy the US, the “watchdog” of global security, would provide benefits such as an increased international recognition for Iran. Therefore, the commitment to achieve the most beneficial outcome is practically equally high for both countries, which means that this indicator cannot serve to offset power imbalances arising from alternatives and therefore reinforces the probability of a stalemate. The third component of Issue-Specific Power, control, is “the degree to which one side can unilaterally achieve its preferred outcome”. If no agreement is reached, either because the negotiations are ended or because they draw on indefinitely, the US has but one option of reaching its goal unilaterally: a military invention in Iran. However, the US has already repeatedly distanced itself from this option (Sebenius & Singh, 2012) due to the high costs of such an undertaking: both the possible ways in which Iran could retaliate directly or indirectly and the financial burden pose significant drawbacks (Long & Luers, 2012). Therefore it seems that the US’s access to control is diminished in comparison to that of Iran, who can unilaterally resume its target of developing a nuclear weapon and already seems to be doing so (Dueck & Takeyh, 2007, p. 191). Although the existing sanctions slow this process, Iran has full control for reaching its target and therefore has an additional motivation for drawing out the stalemate.

The last aspect of power, Behavioural Power, refers to the actors’ ability to make use of their Aggregate Structural and Issue-Specific Power in order to steer the negotiations and to reach an outcome (Habeeb, 1988, p. 23). This implies how well actors can make use of coercive and accommodative means, such as threats and incentives. For example, in order for a threat to be credible, the issuing actor must have the resources to carry it out. Obviously, the US can rely on a large range of resources to make its threats of sanctions very credible and thereby important to Iran. However, its threats of military intervention are lessened due to previous distancing from such an action. On the other hand, making promises as another tool of Behavioural Power, can no longer credibly be made by Iran due to its carefree treatment of the previous agreements it has entered into. This decline in credibility leaves only stalling as a possible tactic for Iran. And as we have previously discussed, Iran has a high interest in drawing the negotiations out from its own secure position. Therefore, while the US originally has a strong Behavioural Power position, it cannot in fact make use of it.

To analyse the effect that personal negotiation styles can have on international negotiations, one faces a major problem: how to get information on how participants of the Iranian Nuclear Talks approach negotiations. During the multilateral meetings, no press was allowed. So the only people that actually know how the talks went are the national representatives themselves. Even if one manages to get a hold of these people, it is questionable whether their self-assessment is reliable. The representatives might want to be seen as cooperative and forthcoming, in order to stifle questions of whether it might have been their fault the negotiations do not go well, while actually taking a competitive approach and using fake cooperation as a feint to gain an advantage over their adversary. Still, as those self-assessments are the only obtainable information, one might use them as a basis of argumentation. To investigate the influence personal negotiation styles can have and to classify which style the individual negotiators represent, I would ask them or their spokesperson the following questions:

- How freely can representatives of international institutions / states rely on their personal approaches to negotiation?

- Does every single bid need to be cleared with the institution / the state they represent?

- Does the negotiator seek to understand and to accommodate the other side’s point of view, or does he more frequently refer to his own position?

- How concerned is the negotiator with the maximisation of joint benefits?

- Will the negotiator rather choose to retain his position and risk non-agreement, or give in for agreement’s sake?

- What level of trust does the negotiator place in the information provided by the other parties of the negotiation?

Questions 1 and 2 seek to investigate how much impact one single negotiator can actually have. Although theories of negotiation assign a large role to the different styles, this assumption might not be applicable to international negotiations. However, I assume that when the highest level of representatives of states or institutions enter negotiations, they do not need to clear every single proposal with the ones they represent. This would mean that there is a certain degree to which negotiators can influence the outcome of a negotiation through personal styles, although I find it doubtful that this impact goes as far as negotiation theories assume. The questions 3 to 6 are aimed at classifying the individual negotiation styles. If the answer to question three is that the negotiator attempts to comprehend the other side, asks them many questions and shows understanding for their point of view, this negotiator shows signs of being cooperative. If on the other hand he refers to only his own point of view and tries to make the other side comprehend their perspective, this is an indicator for a competitive negotiator. Question 4 is likely to be answered in a way that shows the good will of the negotiator. Saying up front that they are only concerned with their own gain would likely worsen the other side’s willingness to cooperate. Still, it would be interesting to see whether this answer offers a contrasting argument to that of question 3, as this could be used to corroborate the point that competitive negotiators tend to “disguise” as cooperative to manipulate their adversaries. Question 5 might pose a dilemma to the interviewee, as neither answer sheds a positive light on the negotiator, especially in the case of the Iranian Nuclear Negotiations. Both the outcome of non-agreement and of an undesirable deal are difficult to justify to those they represent. The cost of both outcome is high, however, non-agreement is exactly what was reached in November 2014. Therefore, it is possible that unaccommodative negotiation styles might have played a role. An answer that confirms that non-agreement is preferential indicates that the negotiator uses a competitive style. Question 6 is not formulated as a direct inquiry on whether or not the negotiator is truthful, because they obviously have to agree to such a question in order to be credible. However, asking how truthful they assume the other side to be can give us just as much insight into their negotiation style: cooperative negotiators assume that their adversaries are equally interested in the maximization of joint benefits and therefore willing to share honest information. If a negotiator assumes that the other side is providing false information, it can be concluded that they approach negotiations from a competitive standpoint. Due to the outcome that was reached and due to the lack of trust the P5+1 exhibit towards Iran, I find it likely that the negotiators all assume a more or less competitive stance. This could, according to negotiation theories lead to either an extremely favourable outcome for one side, or a non-agreement.

During the Iranian Nuclear Negotiations, the country of Oman, represented by their foreign minister Yusuf bin Alawi, has played the role of host for the talks and has worked as mediator (Lee & Klaper, 2014). Seeing that the conflict between the US and Iran about Nuclear issues dates back over 30 years, it is not surprising that both parties are interested in mediation. While it can be assumed that Oman has an interest in a resolution of the conflict for peace’s sake, it can also be assumed that Oman is welcoming this opportunity to enlarge its own influence and that of the Gulf region (Gray, 2014). As with personal negotiation styles, assessing which mediation strategy the mediator used can only be done by interviewing the negotiation parties. Questions for the mediator that could be asked are:

- Did you avoid representing mostly one side’s point of view, and did you seek to establish communication channels between the parties?

- Did you supply missing information and try to clarify?

- Did you arrange the time, location and agenda for meetings and did you chair the talks?

- Did you seek to point out mutual interests, assist parties is avoiding humiliation and work to maintain the negotiations?

- Did you personally endorse negotiators’ proposals or make your own proposals for concessions?

- Did you threaten to withdraw from the negotiations or point out the consequences of non-agreement?

The questions 1 and 2 seek to verify whether the mediator used a facilitative-communicative strategy and thereby acted as “go-between” to help the conflict parties to a better understanding of each other’s point of view (Bercovitch, Lee, 2003). Questions 3 and 4, if affirmed, indicate that the mediator used a procedural-formulative strategy to establish a context in which the conflict might be resolved more easily (ibid.). Lastly, questions 5 and 6 can signal whether the mediator’s strategy was directive and thereby highly interventionist. As it is unfortunately not possible to obtain such answers from the Omani foreign ministry, one can only rely on the assessments of observers of the negotiations’ development, such as that of Trita Parsi, president of the National Iranian American Council, who describes Alawi’s involvement mostly in terms of communication facilitating (Parsi in Gray, 2014). However, due to the fact that Oman hosted several rounds of the negotiations, it is possible that Oman also played the role of procedure formulator by setting up a framework for talks between Iran and the US. In any case, the one strategy that can clearly be excluded is the directive strategy, which means that Alawi never sought to use to intervene more strongly in the negotiations.

To evaluate how successful this mix of facilitative and procedure-formulative strategies was, one needs to establish whether the subjective criterion and the objective criterion were fulfilled. With regard to the former, it seems to be clear that the parties are not satisfied by the outcome of the negotiations. The further extension of talks and the inability of both sides to agree on a deal can be considered a non-agreement, which is undesirable for the US and Iran (although, as pointed out above, Iran could still be able to reach its goal). Therefore, the subjective criterion was not fulfilled and mediation in this regard was unsuccessful. The objective criterion also was not satisfied, as no agreement was reached at all. As both criteria remain unmet, one needs to conclude that mediation has failed. But why did the efforts undertaken by Oman not lead to an agreement? According to theories of international mediation, in conflicts which unravel between countries who exhibit power asymmetries, mediation has a higher likelihood of success than in symmetric conflicts. This should have aided the mediation efforts. However, this success depends on the strategy the mediator used. Manipulative or directive strategies are assumed to be the best suited way to handle mediation, while procedural-formulative strategies will yield worse results and communication-facilitative strategies are most likely to fail. As Alawi pursued less interventionist strategies and did not undertake to actively manipulate the US and Iran into reaching an agreement, the mediation effort was doomed to fail.

Lastly, I will examine how information sharing has affected the Iranian Nuclear Talks. One crucial piece of information, which is highly contested, is the question whether or not Iran has interest in nuclear energy beyond peaceful uses. The official statements concerning this question from Iran’s leadership are that no such interest exists (Sebenius & Singh, 2012, p. 13). If theories of negotiations assumed that every bit of information disclosed is always true, such statements would strongly impact the nuclear talks. In terms of traditional bargaining models, the minimal and optimal desirable outcomes would be changed beyond recognition. The bargaining space would be greatly enlarged, and bids would no longer need to fall between the incompatible goals “Iran is severely restricted” and “Iran retains latent capability”, but could all fall into a range of agreements that severely restrict Iran. It is much more likely that a deal would be reached. Also the game theoretic modelling of the talks would be changed: The negative impact that the US would suffer from Iran’s continuing of enrichment would be lessened which would mean that the US might be less averse to dropping sanctions. Therefore, also this model would speak for a resolution of the conflict, if the US assumed that Iran’s information was correct. If the information were indeed truthful, the information dilemma would lead the US to make wrong assumptions and to thereby miscalculate the costs of concession. However, the course of the previous negotiations and the repeated treaty infringements made by Iran lessen the credibility of its promises in addition to the skepticism prescribed by the information dilemma.

Regardless of whether or not the denial of Iran’s interest in nuclear weapons capability is true, if the US were able to accept it as correct, the negotiations would more likely end in an agreement. This is another way in which an aspect of negotiation theories reconfirms the failure of the Iranian Nuclear Negotiations.

Conclusion

Summary

In this essay I sought to answer the question whether theories of international negotiations could explain the failure of the Iranian Nuclear Negotiations in November 2014. After conducting my research and examining different theories of negotiations I have come to the conclusion that yes indeed, those theories and the aspects they analyse are exceedingly helpful in understanding why Iran and the P5+1 were unable to reach a deal. Traditional bargaining theory revealed that the worst possible outcomes for the two parties were incompatible, making it impossible to find a solution which could satisfy both sides, and that any coercive or accommodating measures would prove fruitless. Game theory very clearly predicts the exact outcome which was produced in the latest round of negotiations: a stalemate between the parties, in which neither is willing to make concessions and in which Iran can more or less comfortable keep pursuing its goal. The theory also helped to explain why making heavy concessions was an impossible option for both sides and why the generally beneficial outcome of mutually accommodating behaviour has not been reached in the talks. The analysis of US-Iranian power relations showed that although the US has, due to its superior Aggregate Structural Power, the upper hand when it comes to employing bargaining tactics such as threats or promises, Iran has the high ground with regard to Issue-Specific Power. It has more alternatives and more control over the outcome, despite the fact that both countries show similar levels of commitment. This distribution of power results – according to negotiation theories – in a stalemate in which Iran will seek to prolong the negotiations while pursuing its goal outside of the talks. Although I was unable to directly interview negotiation parties on their individual negotiation styles, one can reasonably assume, that although the influence single negotiators have on the outcome of multilateral bargaining must be small, it can have certain impacts. Judging by the development the negotiations took and by the failure of the parties to reach an agreement, it can be deducted that the individual styles can all be categorised as competitive, which lowers the chances of a beneficial outcome. Also the mediation strategy used by Oman cannot be verified beyond a doubt due to the lack of transparency into the negotiations. Still, the impression observers had of Alawi’s approach to the talks points at non-interventionist strategies, which are unlikely to succeed in asymmetric negotiations. The last aspect of negotiation theories which I investigated explains why the US cannot trust the information provided by Iran and why it must assume that the worst outcome is indeed a nuclear Iran.

To conclude, all of these theories and aspects of negotiations confirm that the stalemate and the inability by the parties to find a solution were inevitable. While I had expected that at least some theoretical approaches, such as the analysis of power asymmetries, would reveal solutions to the conflict or would be in contradiction to the other theories, it has become evident that all theories point to the same outcome.

Concerning a prediction for the future of the talks, I find it unlikely that the US will find a threat powerful enough to make Iran give up on its nuclear ambitions, which would be the only way to broaden the bargaining space and to find a deal. This means that it is very possible that the negotiations will continue to prove fruitless and will draw on for an indefinite time. During this time it is probable that Iran will continue to work on its nuclear programme and that it will slowly but surely succeed in reaching its goal of nuclear capability. Therefore, it might be time to consider how the world would change if Iran had the bomb. While this is considered a catastrophic outcome by the US leadership, there are some who propose that it would not indeed be a problem, but maybe even desirable. Kenneth Waltz refers to the rationality of the Iranian government in arguing that Iran is on its way to balance out the nuclear hegemony of Israel in the Middle East, which should result in a more stable region, that Iran would be incredibly irrational to actually make use of its nuclear capabilities, that other new nuclear powers have distanced themselves form terrorism and that it is therefore unlikely that Iran will provide terrorist groups with nuclear weapons, and that lastly, Iran’s acquisition of the bomb would not result in a regional arms race, as neither has that of Israel in the 1960s (Waltz, 2012).

Remarks, Limitations and Further Research Needs

One problem one faces when attempting to squeeze a huge issue into a few tiny models is that important aspects will not be done justice. Some questions which could be answered in a work of bigger scope would be which threats the US could actually utter to make Iran give up its nuclear programme? Can such a threat even be found, or is this the entirely wrong approach, and should the US give promises of rewards to Iran? Would such behaviour encourage more countries to provoke a conflict? Which effect does the international climate have on the negotiations, or more precisely, how do the US-Israeli negotiations influence US decision-making? How has the rising time pressure influenced US bargaining behaviour and how will it continue to do so in the future? Is Iran affected by time pressure at all? How does the political system of the countries involved affect their bargaining behaviour? Is a country with more centralised policy making procedures more flexible in negotiations? And the other way round: how does a government “sell” its bargaining behaviour to its people? These are a big pile of questions, leading to even more questions and it seems probable that each one of them will yield information crucial to understanding the negotiation behaviour of the US and Iran.

Another issue when dealing with theories such as game theory, that seek to qualify an abstract issue, demand that one assigns more or less random numbers to issues beyond the grasp of mathematics. While I tried to make arguments for why I used the values that I did, it is entirely possible that any other person would argue differently and assign a different value. For example, while I assumed that a worst outcome scenario would be equally bad for the US and Iran, one might find that in fact, for Iran making unreciprocated concessions might be worse than it would be for the US; or the other way around. This would change the outcome of the game and might be in complete contradiction to my findings.

Lastly, the problem that I faced when I tried to examine individual negotiation styles is that those are not easily researched. There is no press present at the meetings between the countries and one can only rely on official statements issued by the negotiators themselves. Therefore, such self-assessment cannot be verified or falsified, and one can only use their statements as basis of argumentation, but not see them as facts. Still, any such statements would have been useful for the writing of this paper, and the fact that I was unable to reach contact persons willing to be interviewed was frustrating. Even those who had previously agreed to answer a few questions shied away from this favour once I sent the questions listed above. This is either because a Bachelor degree student’s request is not considered worth the effort, or because spokespersons seek to withhold information which could be used against them in upcoming talks. It would be interesting to see whether established journalists and academic researchers would face the same lack of cooperation. The search for information on Oman’s mediation efforts proved equally fruitless and might also only be successful in the hands of professional researchers. I hope to one day read a complete assessment of the Iranian Nuclear negotiations that will answer my remaining questions.

References

Avenhaus, R. (2009) Game Theory as an Approach to Conflict Resolution. In: Bercovitch, J., Kremenyuk, V., Zartman, I.W., The SAGE Handbook of Conflict Resolution, London, SAGE Publications, pp. 86-101.

Arms Control Association (2014) Timeline of Nuclear Diplomacy with Iran, Available from: <http://www.armscontrol.org/factsheet/Timeline-of-Nuclear-Diplomacy-With-Iran> [Accessed on: 06.02.2015].

Bercovitch, J. (2011) Theory and Practice of International Mediation: Selected Essays, New York, Routledge.

Bercovitch, J., Lee, S. (2003) Mediating International Conflicts: Examining the Effectiveness of Directive Strategies, The International Journal of Peace Studies, 8 (1), pp. 1-17.

Brams, S.J. (2003) Negotiation Games: Applying Game Theory to Bargaining and Arbitration, 2nd edition, London, Routledge.

Craver, C.B. (2003) Negotiation Styles: The Impact on Bargaining Transactions, GW Law Publications and Other Works.

Dahl, R.A. (1957) The Concept of Power, Behavioral Science, 2 (3), pp. 201-215.

Dueck, C., Takeyh, R. (2007) Iran’s Nuclear Challenge, Political Science Quarterly, 122 (2), pp. 189-205.

Encyclopaedia Britannica (2014) Iran, Available from <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/293359/Iran> [Accessed on: 10.02.2015].

Encyclopaedia Britannica (2015) United States, Available from <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/616563/United-States> [Accessed on: 10.02.2015].

Gray, R. for Buzzfeed (2014) How A Gulf Monarchy Became A Key Player In The Iran Talks, Available from <http://www.buzzfeed.com/rosiegray/oman-is-playing-a-key-if-low-key-role-in-iran-talks#.nrpVK5Nl42> [Accessed on: 17.02.2015].

Habeeb, W.M., (1988) Power and Tactics in International Negotiation: How Weak Nations Bargain with Strong Nations, Baltimore and London, The John Hopkins University Press.

Lee, M., Klapper, B. for PBS (2014) Kerry Meets with Arab Mediator Ahead of Iran Nuclear Deadline, Available from <http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/kerry-meets-arab-mediator-ahead-iran-nuclear-deadline/> [Accessed on: 17.02.2015].

Lodgaard, S. (2007) Iran’s Uncertain Nuclear Ambitions. In: Mærli, M. B., Lodgaard, S. Nuclear Proliferation and International Security, New York, Routledge.

Long, A., Luers, W. (2012) Weighing Benefits and Costs of Military Action Against Iran, New York, The Iran Project.

Mascheler, M., Solan, E., Zamir, S. (2013) Game Theory, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Murninghan J.K. et al. (1999) The Information Dilemma in Negotiations: Effects of Experience, Incentives and Integrative Potential, The International Journal of Conflict Management 10 (9), pp. 313-339.

O’Sullivan, M.L. for Los Angeles Times (2012) Will Iran Crack?, Available from: <http://articles.latimes.com/2012/jul/06/opinion/la-oe-0705-osullivan-sanctions-iran-20120706> [Accessed on: 09.02.2015].

Quinn, D. et al. (2009) Power Play: Mediation in Symmetric and Asymmetric International Crises. In: Bercovitch, J., Gartner, S.S. International Conflict Mediation: New Approaches and Findings, New York, Routledge.

Sanger, D.E., Gordon, M.R. for The New York Times (2014) US and Allies Extend Iran Nuclear Talks by 7 Months, Available from <http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/25/world/middleeast/iran-nuclear-talks.html>, [Accessed on: 06.02.2015].

Sebenius, J.K, Singh, M.K. (2012) Is a Nuclear Deal with Iran Possible? An Analytical Framework for the Iran Nuclear Negotiations, International Security 37 (3).

Sherrill, C.W. (2012), Why Iran Wants the Bomb and What it Means for US Policy, The Nonproliferation Review 19 (1), pp. 31-49

Snyder, G.H., Diesing, P. (1977) Conflict Among Nations: Bargaining, Decision Making, and System Structures in International Crises, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

The Guardian (2014) Tehran reacts to nuclear deal, Available from: <http://www.theguardian.com/world/iran-blog/2014/nov/25/-sp-iranian-nuclear-talks-tehran-reactions>, [Accessed on: 06.02.2015].

Waltz, K.N. (2012), Why Iran Should Get the Bomb: Nuclear Balancing Would Mean Stability, Foreign Affairs 91 (4), pp. 2-5.

Wolfe, R.J., McGinn, K.L. (2005) Perceived Relative Power and its Influence on Negotiations, Group Decision and Negotiation 14 (1), pp. 3–20.

—

Written by: Alina Ptok

Written at: Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences

Written for: Dr. Dieter Reinhard

Date written: February 2015

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- 1.5 to Stay Alive: The Influence of AOSIS in International Climate Negotiations

- The Puzzle of U.S. Foreign Policy Revision Regarding Iran’s Nuclear Program

- Do Coups d’État Influence Peace Negotiations During Civil War?

- The Right to Be Here: A Case for the Inclusion of Women in Peace Negotiations

- The Instrumentalization of Energy and Arms Sales in Russia’s Middle East Policy

- Rogue Relations under Max-Pressure: Iran-Venezuela Bilateral Engagement 2013–2020