Cross-Communal Sporting Projects (henceforth CCSPs) aim to improve intergroup relations and promote reconciliation in numerous post-war societies. Such projects exist in Israel, Palestine, South Africa (Höglund & Sundberg, 2008), India and Pakistan (Sorek, 2013, 266). Despite their abundance, there is no consensus on their effectiveness. Although some scholars believe that sport can cement existing ties between communities, others stress that sport inflames militant feelings amongst participants and spectators (Sugden & Harvie, 1995). Indeed, national and regional sporting teams are associated with strong ties and feelings which often exclude other groups, as is exemplified by the persistent problem of hooliganism and racism in European football (Jarvie, 1993). This also explains why the theoretical role of sport has divided scholars of the peace process in Northern Ireland. Most aspects of Northern Irish society are divided along religious and communal lines, and sport is no exception. Irish sports, institutionalised by the Gaelic Athletics Association (GAA), and ‘foreign’ sports – those strongly related to British identity (such as rugby, hockey and cricket) – reflect the broader psychological and geographic segregation between the nationalist Catholic community and its unionist Protestant counterpart (Sugden & Barnier, 1993).

Using mixed methods, this essay will examine the extent to which CCSPs have contributed to the reconciliation process in Northern Ireland, and discern between the “ideal” and the “real world” role of sport (Saudners & Sugden, 1997). The first part will outline how sport can promote reconciliation according to relevant literature. We will then statistically test these assumptions within a Northern Irish context. Notably, we test the effect of CCSP participation on (1) people’s attitude towards their out-group and (2) people’s evaluation of intergroup relations. During the research, it became apparent that sport in Northern Ireland could not be understood merely through a quantitative lens. Therefore, the final section will focus on the GAA in order to examine the politicisation and symbolism of sport.

Literature Review and Theoretical Background

CCSPs have existed in Northern Ireland since the ‘Troubles’ started in the 1960s and were the most popular type of reconciliation project in 1997 (Saunders & Sugden, 1997). Yet the value of such projects has come under increasing scrutiny. Indeed, Bairner (2013) questions the foundations of the ‘vague notion’ that sports can improve community relations. Although the mechanisms behind how CCSPs contribute to the process of reconciliation are relatively unexplored, it is possible to place sport into a broader field of reconciliation research. This section will outline the theories which lead both scholars and policy-makers to believe that sport can be an efficient channel for reconciliation.

The reconciliation process is of utmost importance in preventing the resurgence of conflict in post-war societies. Northern Ireland’s Good Friday Agreement is what Boyce describes as a “rough blueprint” towards peace (Boyce, 2002, 8), whereas efforts to change the perception of the out-group, or “mutual acceptance by groups of each other” (Staub, 2006, 868), is a long and ongoing process of reconciliation. The primary focus of reconciliation is to reshape identities, what Kelman calls a process of “negotiating identity” (2010, 3). He states that removing the negation of the other group’s identity as a central component of one’s own identity is key to preventing the re-emergence of conflict (Kelman, 2010, 4). In many respects, conflict resolution has been achieved in Northern Ireland. Reconciliation – when different societies learn to live together – however, is arguably still in its early phases. Sporting initiatives that seek to bring together opposing communities are no doubt part of this process.

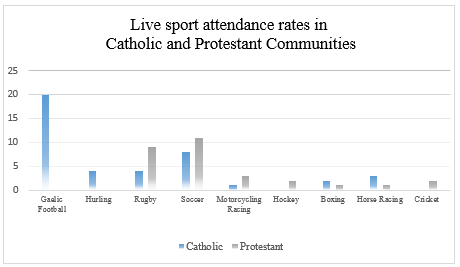

Gordon Allport is credited with the Intergroup Contact Theory or the ‘Contact Hypothesis’, which stipulates that contact between two groups can have positive effects including greater acceptance of the ‘other’ (Pettigrew, 1998, 66). Allport described the ‘in-group’ as a group of individuals that use the term “we” with the same essential significance (Allport, 1979, 31). They usually share the same loyalties and prejudices – some of which are inherited (or “ascribed”), others which are fought for (or “achieved”). Although Allport argues that an out-group is not a precondition for the formation of an in-group, he admits that it can strengthen the in-group’s sense of belonging (1979, 40). The family is the smallest and strongest in-group, but an individual can be part of a number of in-groups which grow weaker as the circle of inclusion becomes larger. Sport in Northern Ireland is still extremely segregated along communal ties (see appendix, figure ii). Although not all Catholics are GAA members, almost all GAA members are Catholic. Therefore, being a GAA member is an in-group within the larger Catholic in-group. It is conceivable that CCSPs bridge the gap between two sporting in-groups by circumventing the larger in-group of religion. Allport lists a number of conditions for effective intergroup contact. The most relevant to this study is that there is support of the authorities, laws and customs. Our analysis of the GAA raises doubts as to whether this condition is present in Northern Ireland.

Barnier (2013) describes CCSPs as giving Irish nationalists the opportunity to play games traditionally associated with the unionist population, and vice versa. In this sense, the goal of CCSPs is to forge mutual understanding and cross-communal integration by changing attitudes and societal institutions. CCSPs in Northern Ireland are not easily categorised into reconciliation project models, but probably fall somewhere between what Maoz (2011) calls the ‘Coexistence Model’ and the ‘Joint Projects Model.’ In essence, it is coexistence, but playing a sport also has elements of working together towards a “common, superordinate goal” (winning) which reduces intergroup hostilities and fosters a common identity (Maoz, 2011, 119). Staub (2006) outlines three reconciliation processes: changing attitudes of people, changing words and actions of those who influence, and creating and changing societal institutions. CCSPs should contribute to changing the attitudes of people and the societal institutions within which people interact. It is striking that Staub does not offer a hierarchy or temporal aspect to these processes. Is one to assume that these processes happen simultaneously, or can one process be instrumental for the development of another?

Maoz (2011) claims that long protracted ethno-political conflicts, like Northern Ireland, create psychological phenomena such as mutual prejudice, de-legitimisation and dehumanisation. The ‘Contact Hypothesis’ suggests that intergroup contact can effectively reduce these prejudices. Bar-Tal (2000) outlines that in order to create a collective ethos, eight societal beliefs must be addressed. Intergroup contact should significantly affect two of Bar-Tal’s societal beliefs: beliefs about the adversary group and beliefs about intergroup relations. Based on these theories, we can extract the following hypotheses:

H1: Individuals who have taken part in a CCSP will have a more positive attitude towards their out-group.

H2: Individuals who have taken part in a CCSP will have a more positive outlook on intergroup relations.

Testing these hypotheses should shed light on the effectiveness of CCSPs in Northern Ireland and the accuracy of relevant reconciliation literature.

Research: Mixed Methods

2.1 A Tentative Quantitative Study

This statistical analysis draws on aspects from a study by Hewstone et al. (2006). Some variables are the same, but the actual models are significantly tailored in order to examine CCSP participation. We used data from the Northern Ireland LIFE & TIMES survey[1], a yearly survey that has its roots in the Northern Ireland Social Attitudes Survey, the same used by Hewstone et al. to explore intergroup contact in 1989. 1210 adults were interviewed for the 2013 survey on issues regarding community relations, minority ethnic people, sport and social exclusion, LGBT issues, political attitudes and personal background information. Importantly for this study, 2013 was the first survey to have a section entirely dedicated to sport.

Like Hewstone et al. (2006), we constructed a variable to measure respondents’ attitudes toward mixing with the out-group based on a five-question scale. The questions asked respondents whether they were in favour of more or less segregation in schools; where people live; where people work; in people’s leisure and sports activities; and in people’s marriages. Higher scores indicated more favourable attitudes towards mixing with the out-group. In their analysis, Hewstone et al. used class and education as explanatory variables for an individual’s attitude to the out-group. We included similar variables in two regression model alongside whether the person’s neighbourhood had experienced rioting in the past year, general levels of happiness and if they had ever taken part in a CCSP.

Two regression models were built in order to test the relationship between CCSP participation and (1) an individual’s perception of their out-group and (2) general intergroup relations.

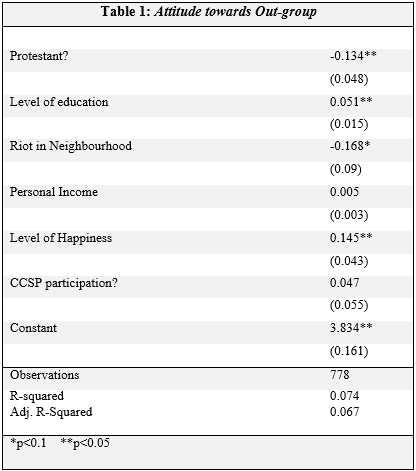

Table 1 was constructed to test hypothesis 1. It shows that there is no statistically significant relationship between taking part in a CCSP and an individual’s attitude towards their out-group. The other independent variables are more effective in explaining what shapes a person’s prejudice or acceptance of the ‘other’. Interestingly, the Protestant community tends to have a slightly more negative attitude towards mixing with Catholics. This may be explained by the political context at the time, notably Belfast’s flag protests in 2012 and 2013 (Bairner, 2013, 227). According to this test, there is no relationship between CCSP participation and an individual’s attitude to their out-group. We therefore fail to reject the null hypothesis and find no evidence to support the assumptions underpinning hypothesis 1.

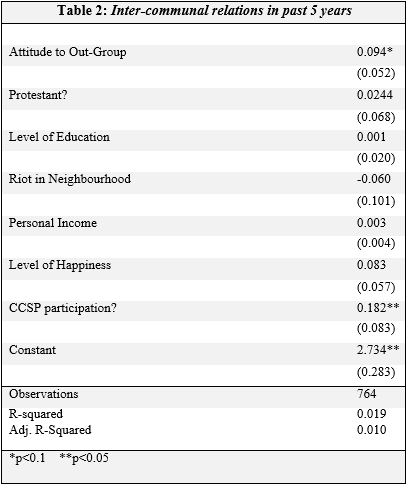

Table 2 shows that there is a positive relationship between an individual’s attitude towards their out-group and the belief that relations between both communities had improved in the past five years. Importantly for this study, having taken part in a CCSP is statistically significant and has a strong effect on the dependent variable. Therefore, this model supports hypothesis 2 – individuals that take part in CCSPs are more likely to have a positive outlook on intergroup relations. It is important to draw attention to a low adjusted R-squared score, which shows that the model only accounts for 1% of the variance of our dependent variable. We are trying to explain human sentiments and therefore expect a low R-squared. It is still possible to draw inferences from statistically significant results. This test indicates that CCSPs have a positive effect on participants’ outlook on intercommunal relations.

2.2 The GAA: an institution not yet reconciled

A qualitative analysis of the GAA shows that the mixed results of our explorative statistical investigation is best explained by the lack of reconciliation in sport as a societal institution. This section will examine a number of issues which challenge the GAA’s ability to promote inter-group contact.

The GAA was founded in 1884 and ever since has possessed an “undeniably political persona” (Hassan, 2003, 92). It was part of the ‘Gaelic Revival’, a time when the movement for a more independent Ireland was growing in support and leading figures in Ireland sought to encourage the renaissance of a distinctively Irish identity. The principle aim of the movement and the GAA was to organise opposition to British cultural hegemony in Ireland (Hassan, 2003). The founding fathers of the GAA were Fenians and GAA sporting events were often used by the Irish Republican Brotherhood to recruit (Connell, 2011, 66). The history of the GAA is strongly related to the Irish struggle for independence and the re-emergence of an Irish identity. This, to a certain extent, remains true today. Indeed, the GAA’s mission statement still emphasises the aim to “develop and promote Gaelic Games at the core of Irish identity and culture.”[2]

The GAA’s relationship with nationalism has been well-studied and documented. Saunders & Sugden (1997, 39) claim that sport is one of the most significant forums within which people in Northern Ireland can display their community identity and, especially relevant to the GAA, their political aspirations. In the same vein, Hassan (2010, 99) describes the GAA as a “sporting manifestation of their [nationalists in Northern Ireland] political utopia.” The political nature of the GAA make it a prime target of sectarian attacks. A report by the Institute for Conflict Research presents figures of sectarian attacks on “properties that have specific symbolic value” between 1994 and 2005, and naturally list GAA clubs alongside Orange Halls and churches (Jarman, 2005, 14). Until recently, two GAA rules added to the political personality of the institution. Rule 21 (abolished in 2001) prevented members of the British Armed Forces or British police personnel in Ireland from becoming GAA members. Rule 42 (amended in 2005) effectively banned soccer and rugby from being played on GAA grounds (Fulton & Bairner, 2007). Scholars agree that the GAA has historically played an important political role for nationalism in Northern Ireland. By banning or amending these controversial rules, the GAA is clearly taking steps to promote reconciliation.

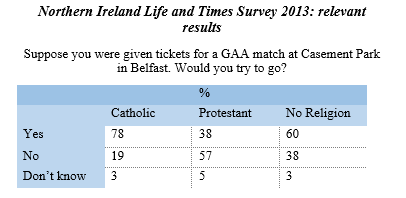

The naming of GAA clubs and grounds has received greater attention in Irish media than from scholars of reconciliation. “Hill 16” and “the Hogan Stand” in Croke Park commemorate the Easter Rising and the Tipperary footballer who was killed on Bloody Sunday, when British forces opened fire on spectators and players during a game of Gaelic football in 1920 (Fulton & Bairner, 2007, 62). The GAA’s main ground in Belfast is named after Roger Casement, a republican hero and British traitor (Sugden & Barnier, 1993, 173). The naming of GAA grounds and clubs continues to cause tension in Northern Ireland. In 2013, the day after Stormont First Minister Peter Robinson commended the GAA for its role in improving community relations, Joe Brolly, a GAA pundit and former player for County Derry, defended the naming of his home club after a republican hunger striker, Kevin Lynch, and told reporters that “people can either like it or lump it.”[3] This received strong criticism by the Protestant community, and Unionist leader Jim Allister claimed that Joe Brolly’s remarks underscored how “foolish” Peter Robinson was in praising the GAA for “supposedly reaching out across the divide.”[4] The names of certain GAA clubs and grounds automatically repel the protestant community from taking part in or supporting GAA sports. In 2013, only 38% of Protestants said that they would try to attend a GAA match in Casement Park if they were given tickets, compared to 78% of Catholics (see appendix, table i).

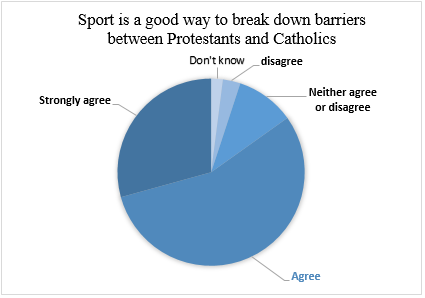

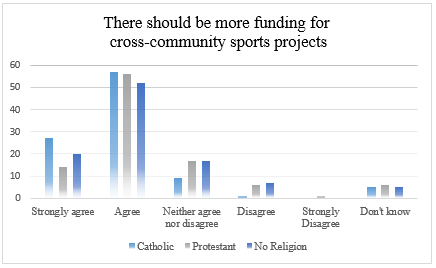

The relationship between the GAA and the Catholic community in Northern Ireland remains strong. Indeed, live sport attendance rates in Catholic and Protestant Communities in 2013 show a clear segregation in sport (see appendix, figure ii). Despite this, an overwhelming majority of people from both communities believe that sport is a good way to break down barriers between Protestants and Catholics (see appendix, figure iii) and that there should be more funding for CCSPs (see appendix, figure iv). Our findings do not support these public opinions. There is an “ideal” role that sport should play and possibly can play, but it is still too early in Northern Ireland. Sport still plays a prominent role in shaping the identity of conflicting groups, and therefore, we argue that sporting institutions like the GAA are too polarised to be used as vehicles of the reconciliation process.

The GAA is an extreme case. According to figures ii and iii, it is the institution that is most affiliated with one of the two conflicting communities. Nevertheless, it sheds light on the nature of sporting institutions in Northern Ireland. Removing politically significant and contentious bans is a step towards making the GAA more accessible to both communities. However, the political and ideational symbolism of the GAA, exemplified by the naming of its clubs and grounds, hinders its ability to house intergroup contact. This no doubt explain the weak or non-existent relationship between CCSP participation and indicators of reconciliation found in section 2.1.

Conclusion

These findings have important implications on reconciliation theory and policy in Northern Ireland. Staub’s three processes of reconciliation remain relevant. However, as sport in Northern Ireland shows, the rate of reconciliation within one process may have the ability to impede or enhance reconciliation in others. The GAA is a societal institution which is almost exclusively Catholic. This is due to historical significance and sectarian violence targeting the GAA, but also through its own making, exemplified by the naming of its grounds after prominent nationalist individuals and controversial internal regulations. It shows that the GAA, and possibly sport in general, is still too politicised. This, we argue, diminishes its ability to change the attitudes of people.

The results of this research have important implications for policy-makers. Stormont should not seek to expand CCSPs, especially those between GAA and non-GAA sports. Instead, other avenues should be pursued. It is important that the GAA carries out reforms before it can play a more prominent role in Northern Ireland’s reconciliation process. Abolishing and amending regulation that fosters segregation is a step in right direction, but more needs to be done. More broadly, our findings substantiate the idea that there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to reconciliation. Although we find that sport is not an effective vehicle for reconciliation in Northern Ireland, this does not mean that sport cannot play a role in other post-conflict societies. Instead, our key finding is that reconciliation projects should be avoided within societal institutions that remain too politically and ideationally symbolic.

Appendix

Source: ARK. Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey, 2013 [computer file]. ARK www.ark.ac.uk/nilt [distributor], June 2014.

Bibliography

Books

Allport, G. (1979). The Nature of Prejudice. US: Basic Books

Boyce, J. K. (2002). Investing in Peace: Aid and Conditionality after Civil Wars. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Jarvie, G. (1993). ‘Sport, nationalism and cultural identity’. In: Allison, L., (ed.), The Changing Politics of Sport. UK: Manchester University Press

Sorek, T. (2013). ‘Sport, Palestine, and Israel’. In: Andrews, D., Carrington, B., (eds.), A Companion to Sport. US: Wiley-Blackwell

Sugden, J., Barnier, A. (1993). ‘National Identity, community relations and the sporting life in Northern Ireland’. In: Allison, L., (ed.), The Changing Politics of Sport. UK: Manchester University Press

Sugden, J., Harvie, S. (1995). Sport and Community Relations in Northern Ireland: Centre for the Study of Conflict. UK: University of Ulster

Journal Articles

Bairner, A. (2013). ‘Sport, the Northern Ireland peace process, and the politics of identity’, Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 5:4, pp. 220-229

Bar-Tal, D. (2000). ‘From Intractable Conflict Through Conflict Resolution to Reconciliation: Psychological Analysis’, Political Psychology, 21:2, pp. 351-365

Connell, J. (2011). ‘Countdown to 2016: The GAA and the development of nationalism’, History Ireland, 19:2, pp. 66

Fulton, G., Bairner, A. (2007). ‘Sport, Space and National Identity in Ireland: The GAA, Croke Park and Rule 42’, Space and Polity, 11:1, pp. 55-74

Hassan, D. (2003). ‘Still Hibernia Irredenta? The Gaelic Athletic Association, Northern Nationalists and Modern Ireland’, Culture, Sport, Society, 6:1, pp. 92-110

Hewstone, M., Cairns, E., Voci, A., Hamberger, J., Niens, U. (2006). ‘Intergroup Contact, Forgiveness, and Experience of ‘The Troubles’ in Northern Ireland’, Journal of Social Issues, 62:1, pp. 99-120

Höglun, K., Sundberg, R. (2008). ‘Reconciliation through Sports? The case of South Africa’, Third World Quarterly, 29:4, pp. 805-818

Jarman, Neil. (2005). No Longer A Problem? Sectarian Violence in Northern Ireland, (Commissioned by Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister; OFMDFM), Belfast: Institute for Conflict Research

Kellan, H. (2010). ‘Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation: A Social-Psychological Perspective on Ending Violent, Landscapes of Violence, 1:1, 1-9

Maoz, I., (2011). ‘Does Contact Work in Protracted Asymmetrical Conflict? Appraising 20 Years of Reconciliation-aimed Encounters between Israeli-Jews and Palestinians’, Journal of Peace Research, 48:1, pp. 115-125

Pettigrew, T. (1998). ‘Intergroup Contact Theory’, Annu. Rev. Psychol., 49, pp. 65-85

Saudners, E., Sugden, J. (1997). ‘Sport and community relations in Northern Ireland’, Managing Leisure, 2:1, pp. 39-54

Staub, E. (2006). ‘Reconciliation after Genocide, Mass Killing, or Intractable Conflict: Understanding the Roots of Violence, Psychological Recovery, and Steps toward a General Theory’, Political Psychology, 27:6, pp. 867–894

Online Newspaper Articles

Young, D. (2013). Joe Brolly: ‘It’s nobody’s business if GAA clubs are named after dead republican paramilitaries’. The Irish Independent. [Online] 18 October 2013. Available from: www.independent.ie [Accessed on 17/04/2015]

Footnotes

[1] ARK. Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey, 2013 [computer file]. ARK www.ark.ac.uk/nilt [distributor], June 2014.

[2] https://www.gaa.ie/about-the-gaa/mission-and-vision/

[3] Young, D. (2013). Joe Brolly: ‘It’s nobody’s business if GAA clubs are named after dead republican paramilitaries’. The Irish Independent. [Online] 18 October 2013. Available from: www.independent.ie [Accessed on 17/04/2015]

[4] Ibid

Written by: Christopher Rickard

Written at: University College London

Written for: Dr. Kristin Bakke

Date written: March 2015

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Group Rights and the Protection of Individual Autonomy

- Taiwan’s Democratisation and China’s Quest for Cross-Strait Reunification

- The Constraints of Transitional Justice in Promoting Intergroup Reconciliation

- Overcoming Empire’s Seduction: Decolonizing International Relations

- Pinkwashing the Occupation: Narratives of Interracial Gay Relations in Israeli Film

- A Geostrategic Explanation of India-Myanmar Bilateral Relations since the 1990s