“I’m Not A Feminist, But…”: An Investigation into the Attitudes of University of Kent Students who Identify with the Objectives of the Feminist Movement But Do Not Identify as a Feminist

1. INTRODUCTION

This dissertation addresses issues surrounding modern feminism and how young people are identifying with the feminist label. Although there is a wealth of variations of feminism, and thus multiple definitions which can be discussed in great detail, this project is going to understand the term as follows: the advocacy of women’s rights on the grounds of political, social, and economic equality to men. Given this definition it is evident that a key focus of feminism is equality. However, for many the term has lost this initial meaning and as a result there is often a Jekyll and Hyde quality to how feminists are perceived, wherein they are both widely admired and reviled (Edley and Wetherell, 2001). Although there are many who support both feminists and the feminist movement, there are also those who associate the term feminist with increasingly negative connotations, such as the misconception that all feminists are stereotypical man-hating activists who believe that men are the cause of all the problems in this world. Research suggests that it may be this negative stigma around the feminist label which can influence both men and women to not identify as a feminist, despite often agreeing with many feminist objectives (Anderson, 2009).

In efforts to neutralise the negative stigma which surrounds feminism in recent years there has been an increase of online publicity for the feminist cause, with A-list celebrities such as Emma Watson speaking out about gender inequality. In September 2014, Emma Watson appealed for people to pledge “to take action against all forms of violence and discrimination faced by women and girls” as part of the UN HeForShe campaign (HeForShe, 2015). To date (April 2015) this appeal has received support from almost 28,000 individuals from across the globe. Given this promotion from the UN it is evident that the pursuit of gender equality is both a contemporary and important issue to be discussed in modern politics. Furthermore it is not restricted to the pursuits for equality in the domestic sphere, with Whitworth (2008: 104) suggesting that in paying “greater attention to gender” we can “enrich our understanding and expectations associated with international security”.

Additionally, there has been an increase of civilian feminist activism online which some have ventured to identify as the fourth wave of feminism in which inequality can be challenged using social media as a platform (Munro, 2013). Examples include the #YesAllWomen and #BringBackOurGirls campaigns. #YesAllWomen became popular in May 2014 and created a community where individuals were able to share examples of everyday misogyny and showcase how it is so deeply rooted within society that it is often overlooked. The #BringBackOurGirls campaign arose in the wake of the internationally reported kidnapping of 300 girls in Nigeria in April 2014 and was endorsed by world renowned personalities such as Michelle Obama and Malala Yousafzai via Instagram.

However, despite positive publicity surrounding feminism in recent years, there are still those who actively disassociate with the label. For example, there are the ‘why I don’t need feminism’ and ‘meninist’ movements which have gained momentum through the use of social media, particularly focusing on Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr as platforms. It is interesting to note that a prevalent theme raised in both movements is the focus on believing in gender equality. Both campaigns scrutinize feminism for promoting female pre-eminence at the expense of men. This is an example of how there are those who no longer understand feminism by its aforementioned definition of equality, and have let negative stereotypes skew their perceptions of an entire movement. The UN Deputy Secretary General recently contested this perception that feminism is a female-centric movement, stating that in support of the feminist cause one is supporting the “emancipation of mankind as a whole … We are all benefitting, we are all strengthened, we are all empowered by gender equality” (UN.org, 2015).

This report is going to investigate a selection of these aforementioned negative stereotypes in endeavouring to gain an understanding of some of the factors which influence young people to disassociate with the feminist label despite supporting many of the objectives of the feminist movement. It will build on existing research in this field which identifies the phenomena and postulates that this disassociation with the feminist label is heavily influenced by the negative stereotypes that are deeply rooted in the perception of the movement that many people have. Although this relationship is postulated by scholars, it is has not been investigated and thus this report will be addressing this gap in the literature. This will be achieved through the completion of self-report questionnaires and follow-up focus groups from university students. This research is valuable to the field of study because in gaining a deeper understanding of the negative stigma around the feminist label only then will it be possible for society to work to eradicate it.

In the wake of research conducted by Anderson (2009) it is expected that negative stereotypes will be found to be the primary factor that influences individuals to disassociate with the feminist label, even when they agree with its objectives. However, given that it has been six years since Anderson conducted her research, an overall increase in association with the feminist label is predicted. This is in light of the suggestion that we are currently in a fourth wave of feminism (Munro, 2013), and research by Duncan (2010) identifies a positive correlation between the prevalence of feminism during the generation that an individual grows up, and the strength of their personal feminist identification. This literature will be discussed at greater length in the literature review.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

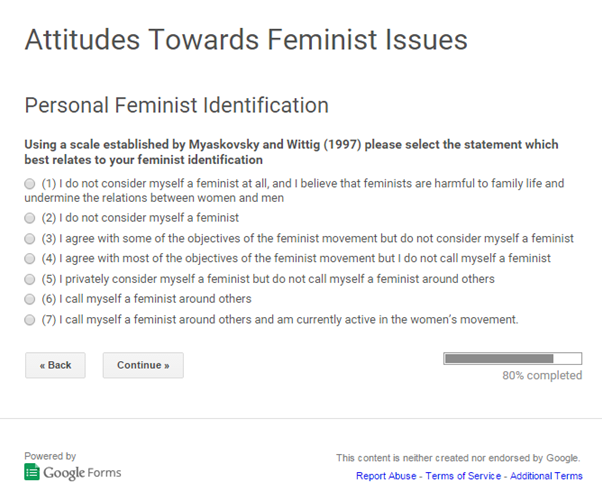

Anderson (2009) conducted a study in which 404 university students were asked to rate either men, women, feminist men or feminist women on 65 semantic differential scales that included measures of characteristics such as tame-ferocious, rational-irrational, homosexual-heterosexual and attractive-unattractive. On completion of this they were then asked to provide their personal information including their feminist identification. Feminist identification was measured using a scale established by Myaskovsky and Wittig (1997) in which a high score indicated strong feminist identification. Anderson (2009) found that the majority of women (45.4%) agreed with some of the objectives of the feminist movement but chose not to identify as a feminist, whilst this was the second most popular finding in men, with 32.6% agreeing with some feminist objectives, yet not identifying as a feminist. Further lack of association with the feminist label was seen with 17.9% of women and 7% of men agreeing with most of the objectives of the feminist movement, yet not identifying as a feminist. The minority of both female and male participants, 6.6% of women and 0.8% [n=1] of men, stated that they would identify themselves as a feminist either privately or publicly.

On evaluation of the responses to the semantic deferential scales which measured participant’s views on the characteristics of men, women, feminist men or feminist women, Anderson (2009) found that there was significant variation in the ways in which feminist men and women were viewed. Feminist men were associated with “more stereotypically feminine characteristics (i.e., cooperative, affectionate, patient … and weak, emotional, and submissive)” (Anderson, 2009: 212), whilst feminist women were rated lower in these categories and were thus deemed less feminine. Furthermore feminist women received low ratings on the attractiveness measure.

Twenge and Zucker (1999) similarly found that there were negative connotations with regards to both feminist men and women in their study. They asked students to react to one of two statements: ‘Michael calls himself a feminist’, or ‘Michelle calls herself a feminist’. Despite some positive reactions towards ‘Michael’ and ‘Michelle’, there were a significant number of negative reactions. Students mentioned overly assertive behaviour in response to ‘Michelle’ whilst more comments on homosexuality were seen in reaction to ‘Michael’. Contrastingly Breen and Karpinski (2008), whose study similarly relied on open-ended responses to hypothetical feminist males and females, found that feminist women were in fact viewed more favourably than their non-feminist counterparts. However this was not found to be true for feminist men. Given this, it would suggest that negative feminist stereotypes are more prevalent in men than women. Perhaps this would go some way to explaining why Anderson (2009) found that men were more reluctant than women to identify themselves as feminists.

Anderson (2009) suggests that the negative connotations which are widely seen to be associated with the feminist label for both men and women have created undesirable stereotypes. Although she postulates that it is because of this that both men and women are resistant to identifying as a feminist, she does not provide definitive causal evidence. Prati et al (2015) recognises that stereotypes can be both persistent and persuasive problems within modern society. Research has shown that if members of a group are aware of prejudice and discrimination towards the said group, they may worry that they will be perceived through negative stereotypes and thus treated undesirably (Steele, Spencer and Aronson, 2002). In the context of this project, this identifies how the prevalence of negative feminist stereotypes may be a motivator for individuals to disassociate with the feminist label, despite supporting feminist objectives.

Contrastingly, Duncan (2010) suggests that the generation in which an individual is raised affects their feminist identification. Her research found that women born between 1943 and 1960, known as ‘Baby Boomers’, were more likely to strongly identify as a feminist than ‘Generation X-ers’, born between 1961 and 1975. Duncan draws on research from Stewart and Healy (1989) who argue that significant social events that occur during an individual’s younger years will affect their fundamental values and expectations. She suggests that ‘Baby Boomers’ identify more strongly than their ‘Generation X’ counterparts because they were “young adults during the heyday of the second wave of feminism” and thus “were more likely to incorporate into their developing identities the notion of themselves as feminists” (Duncan, 2010: 505). On the other hand ‘Generation X-ers’, who were young adults during the feminist backlash of the 1980s, have a weaker feminist identification. In a similar vein, Aronson (2003) identifies that since the early 1980s

women in their teens and twenties [have been labelled] the “postfeminist generation”, … who are thought to benefit from the women’s movement through expanded access to employment and education … [but] do not push for further political change (p.904).

If this continues to hold true, this study would expect to find that the reasons behind feminist disassociation are related to a feeling of contentment of the present generation with the current status quo. However, the recent surge of online activity where “the internet has created a culture in which sexism or misogyny can be ‘called out’ and challenged” (Munro, 2013), has led some to suggest that we may be in the midst a fourth wave of feminism. This in turn would suggest that, in correspondence with Duncan’s (1989) study, the current generation’s young adults’ experience of this fourth wave would affect their values and expectations and thus their feminist identification. It could therefore be expected, in contrast to what Anderson (2009) proposes, that deep-rooted negative feminist stereotypes affect an individual’s willingness to identify as a feminist, and that an increase in feminist identification would instead be seen. This however must be viewed cautiously as it is a bold claim to suggest we are amidst a fourth wave of feminism without hindsight.

3. RESEARCH QUESTION AND HYPOTHESES

This project aims to build on existing research that finds that the majority of people agree with the objectives of the feminist movement, but do not identify as feminists. Current literature identifies negative stereotypes associated with the feminist label, and postulates that disassociation with the feminist label is due to these; however there has been no further investigation into this relationship. This dissertation aims to address this gap in the literature and to gain an understanding of this disassociation with the feminist label, primarily building upon the aforementioned research by Anderson (2009).

It should be noted that there are limitations to this study. It is not claiming to investigate the causes behind feminist disassociation, but rather aiming to understand some of the factors that may influence people’s reluctance to identify as a feminist, which have been overlooked in the current literature.

The research question for this project is:

- What are the primary factors that influence University of Kent students who agree with the objectives of the feminist movement to disassociate with the feminist label?

Based on the research discussed in the literature review which postulates that negative stereotypes will be an influential factor on disassociation with the feminist label this dissertation will be tested using the following research hypotheses:

- Research Hypothesis One H1: Negative feminist stereotypes are the primary influence on disassociation with the feminist label for University of Kent students who agree with the objectives of the feminist, but do not identify as feminists.

- Null Hypothesis One H0: Negative feminist stereotypes are not the primary influence on disassociation with the feminist label for University of Kent students who agree with the objectives of the feminist, but do not identify as feminists.

Subsidiary to H1, this research will also test an additional two hypotheses, which cover issues of the effect of gender and ones’ generation in their willingness to identify as a feminist. Such factors have been identified in the literature as potentially influential.

- Research Hypothesis Two H2: Men are more likely to disassociate with the feminist label than women, despite agreeing with the objectives of the feminist movement.

- Null Hypothesis Two H0: There is no gender influence in an individuals’ willingness to disassociate with the feminist label despite agreeing with the objectives of the feminist movement.

- Research Hypothesis Three H3: There will be an increased percentage of individuals openly identifying as a feminist than seen in research by Anderson (2009).

- Null Hypothesis Three H0: There will be no difference in percentage of individuals openly identifying as a feminist than seen in research by Anderson (2009).

4. METHODOLOGY

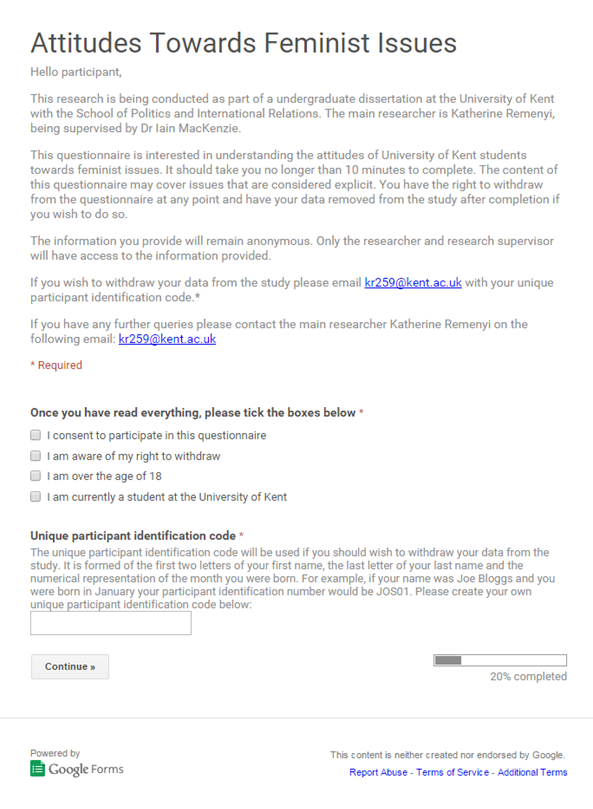

As the study calls for interaction with people this project required ethical approval, which was granted by the University of Kent. O’Leary (2005: 51) recognises that ethical studies must take “responsibility for the integrity of the production of knowledge and ensures that the mental, emotional and physical welfare of respondents is protected”, and these values have been prioritised throughout this project.

Data for this investigation was collected in two parts. Firstly, data which aims to determine how far participants agree with the objectives of the feminist movement and their personal feminist identification was collected through a questionnaire. On completion those who agreed with the objectives of the feminist movement, but disassociate with the feminist label, and who consented to take part, participated in focus groups which endeavoured to gain an understanding of the factors that influence their feminist disassociation.

4.1 Questionnaires

4.1.1 Background to Method

The questionnaire was distributed online, making it both cost and time efficient. Ruane (2005: 123) recognises this as the key strength of using questionnaires, noting that although they “lack the personal touch of the interview”, it is an extremely efficient data collection tool. The use of questionnaires made it possible to enquire into a number of issues, whilst at the same time reaching a substantial number of people. The questionnaire was hosted online by Google Forms, a popular and secure questionnaire hosting site, which assures full ownership of collected data to the creator of said questionnaire. Additionally Google Forms provided automated tabulation of the raw data which reduces data input work and subsequent risks of human error. Furthermore, as this section of the project required a structured approach, the use of questionnaires is ideal as all participants answered the same questions, measured on the same scale, making the data easy to process when searching for participants who meet the requirements for the second focus group section of the project.

4.1.2 Participants

Participants were University of Kent students and therefore it was expected that the age rage will be from 18-25. An understanding of the English language was also assumed. The questionnaires were distributed to my peers, as well as on public University of Kent forums, via Facebook. Participants were limited to University of Kent students to enable the study to focus on a specific group of people and to draw conclusions on this population. Data collection relied on a snowballing effect of participants passing the questionnaire on to their peers in order receive a substantial number of responses. Ruane (2005: 117) recognises that snowball sampling may be limiting in that “individuals who are “loners,” who are not “networked” with others in the research population, will likely be excluded”. Despite this, it was chosen as it was the most efficient method given time limitations.

Overall there were 95 responses to the questionnaire, however when cleaning the data responses from 8 students were excluded. Of these, 4 participants had answered the concentration question incorrectly and a further 4 participants had left fields blank. This left a sample of 87 students comprised of 57 females and 30 males, with ages ranging from 18-26.

4.1.3 Design

On opening the questionnaire participants received a short but concise briefing of the study (see Appendix 1). They were informed of the intent of the study, assured that the data will remain anonymous and that only the researcher and research supervisor will have access to the raw data. They were also provided with the researchers’ email and informed that they may make contact to remove their data from the study at any point they wish. Furthermore they were told they may request additional information on the study or its findings if they wished.

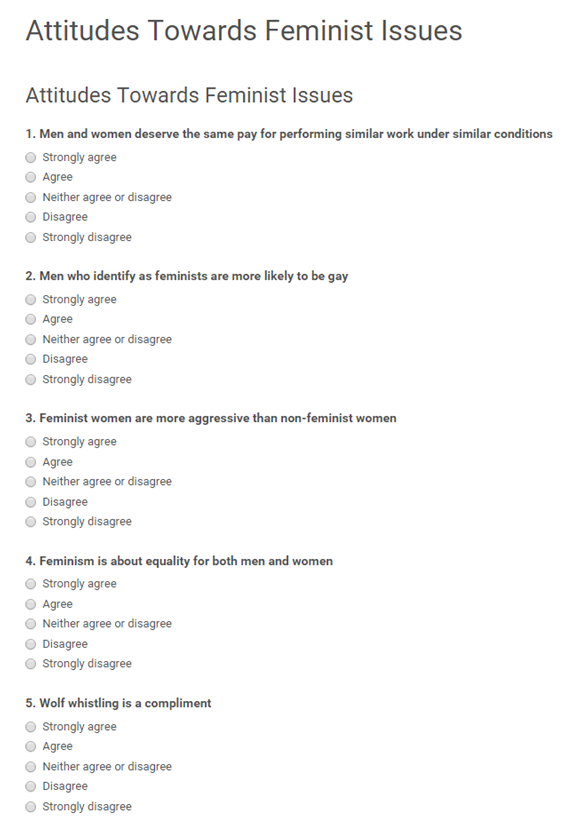

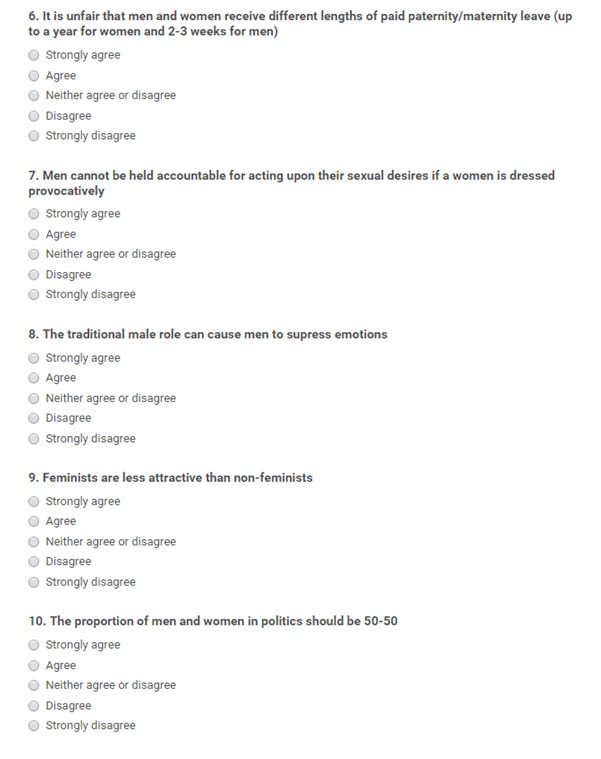

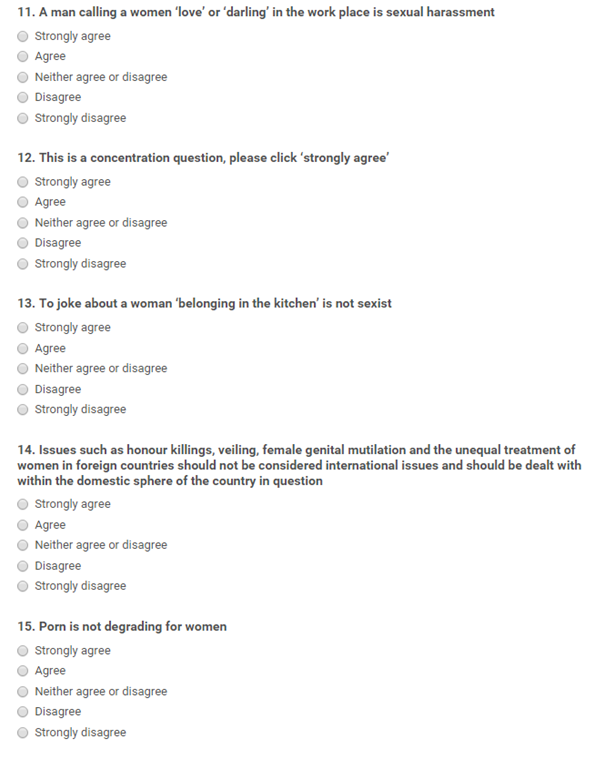

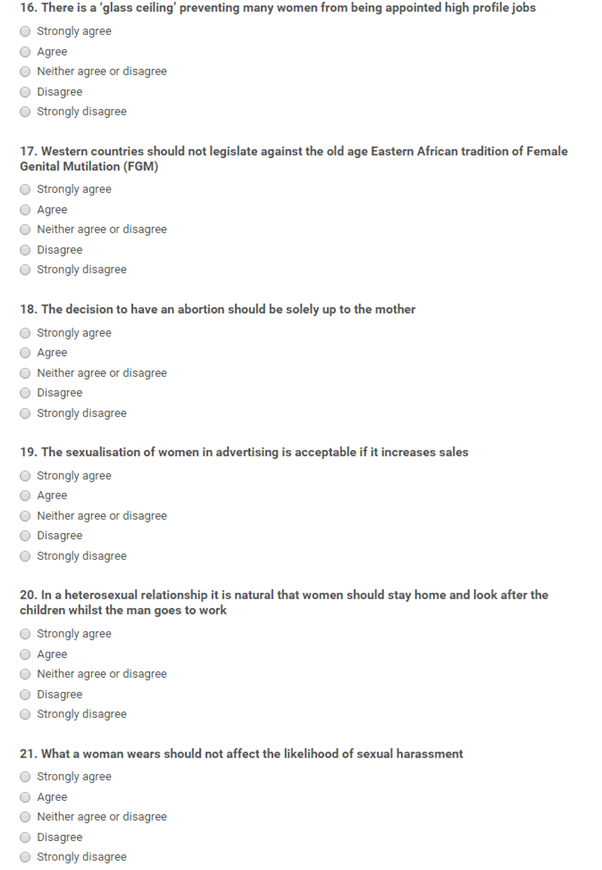

The online questionnaire consisted of two sections (see Appendix 2). Section one aimed to understand how far the participant agrees with the objectives of the feminist movement and consisted of 21 questions, 20 of which focused on feminist issues and one concentration question. The questionnaire took no longer than ten minutes to complete, and it was hoped that in keeping it concise it would maximize the number of participants willing to give their time to the research project. The questionnaire was developed from that of Anderson (2009) and covered topics which are widely discussed both by feminists and by others with regard to feminists. The second part of the questionnaire collected the participant’s personal information: age, gender, feminist identification. No personal data from which the participants could be identified was collected. Feminist identification was identified through a measure established by Myaskovsky and Wittig (1997) in which participants are asked to pick from one of the following statements: (1) I do not consider myself a feminist at all, and I believe that feminists are harmful to family life and undermine the relations between women and men; (2) I do not consider myself a feminist; (3) I agree with some of the objectives of the feminist movement but do not consider myself a feminist; (4) I agree with most of the objectives of the feminist movement but I do not call myself a feminist; (5) I privately consider myself a feminist but do not call myself a feminist around others; (6) I call myself a feminist around others; and (7) I call myself a feminist around others and am currently active in the women’s movement. Higher scores on Myaskovsky and Wittig’s scale indicate stronger feminist identification. At the end of the questionnaire participants were asked for permission to contact them at a later date to take part in a focus group to further understand their responses. If they answered yes, they were asked to provide their University of Kent email, through which it would not be possible to identify them. They were given the opportunity to say no to this question.

4.2 Focus Groups

4.2.1 Background to Method

Interviews were considered as a method for the second section of this research project as they share many of the appealing features of the focus group, in that they facilitate the exploration of a participant’s views, motivations and beliefs. Ultimately focus groups were chosen for the second part of this investigation, primarily because they are more time efficient. However, they have also been identified as being particularly useful in attitudinal research, which is the focus of this project. Ritchie (2014: 56) suggests that focus groups

involve discussion and hearing from others, and give participants more opportunity to refine what they have to say … Explaining or accounting for attitudes is sometimes easier for people when they hear different attitudes, or nuances on their own perspective against this backdrop.

4.2.2 Participants

Out of the 87 responses to the initial questionnaire, there were 40 participants who met the focus group conditions, which were that they agreed with the objectives of the feminist movement yet did not identify themselves as a feminist. This was determined by whether they openly identified as agreeing with most of the objectives of the feminist movement but do not call themselves a feminist (number 4 on the Myaskovsky and Wittig (1997) feminist identification scale), or had a feminist score the same as or higher than those in the aforementioned category.

Feminist score was determined by responding to each question with a numerical value between 1-5, where a response that was more feminist received a higher score. For example, for the statement “Feminism is about equality for both men and women”, the response Strongly agree was given a score of 5, Agree was given 4, Neither agree or disagree was given 3, Disagree was given 2, and Strongly Disagree was given 1. There were a number of reverse scored questions which needed to be accounted for and translated into positive scales before their analysis. Scores were assigned for each response to every question and the mean for each data set was calculated, thus determining the participant’s feminist score. Feminist scores ranged from 3.4-4.6 for those who agreed with most of the objections of the feminist movement, yet did not identify as feminists (number 4 on the feminist identification scale). Therefore it was decided that participants who did not publicly or privately identify themselves as feminists, yet had a feminist score of over 3.4 were deemed to meet focus group conditions. Of the 40 participants who met these conditions, 16 of them provided their emails to be contacted at a later date to participate in focus groups.

It was expected that there would be 2-3 focus groups with 5-7 participants in each. Fewer participants might limit the conversation, and too large a group may result in some participants being excluded from the discussion. Furthermore, although the focus groups have no set time limit, they were expected to last between 30-45 minutes as this amount of time is enough to collect a significant amount of data whilst still keeping the participants engaged. However, despite these expectations, the logistics of coordinating focus groups within a limited time period meant that only one focus group, comprised of 7 participants and lasting 30 minutes, was held. This generated some limitations, which will be discussed later.

4.2.3 Design

At the beginning of the focus group participants were told that the investigation was interested in their personal opinions and their understandings of the issues that were to be discussed, reassuring them that there was no right or wrong answer. Furthermore, they were reminded that their responses would remain anonymous. The focus groups were structured around a collection of predetermined open-ended questions (see Appendix 3), enabling the discussion to flow freely whilst also covering points which are key to the investigation. The questions stemmed from the issues which were covered in the questionnaire and aimed to get a further understanding of the participants’ attitudes towards feminism, and their personal disassociation with the feminist label.

5. RESULTS

This dissertation has utilized both quantitative and qualitative research methods in its pursuit of gaining a further understanding of factors which may influence an individuals’ reluctance to identify as a feminist despite agreeing with the objectives of the feminist movement. However, the quantitative data collected via questionnaires was primarily used as a tool for identifying those who met the focus group conditions. Given this, statistical analysis of the quantitative data will not be extensive as it is through analysis of the focus group findings that the research question will primarily be addressed.

5.1 Questionnaires

Before carrying out analyses on the data collected from the questionnaires it is important to check it for any abnormalities and its suitability to particular tests. After removing 8 responses and allocating the participants with feminists scores (as discussed in the methodology) the cleaned data comprised 87 responses. However in the questionnaire addressing participants’ views on feminist issues, there were a number of reversed scored items. These items needed to be reversed in order to create all positive scales to analyse. Raw data collected from the questionnaires can be seen in Appendix 5, and cleaned data in which all responses are measured on positive scales are in Appendix 6.

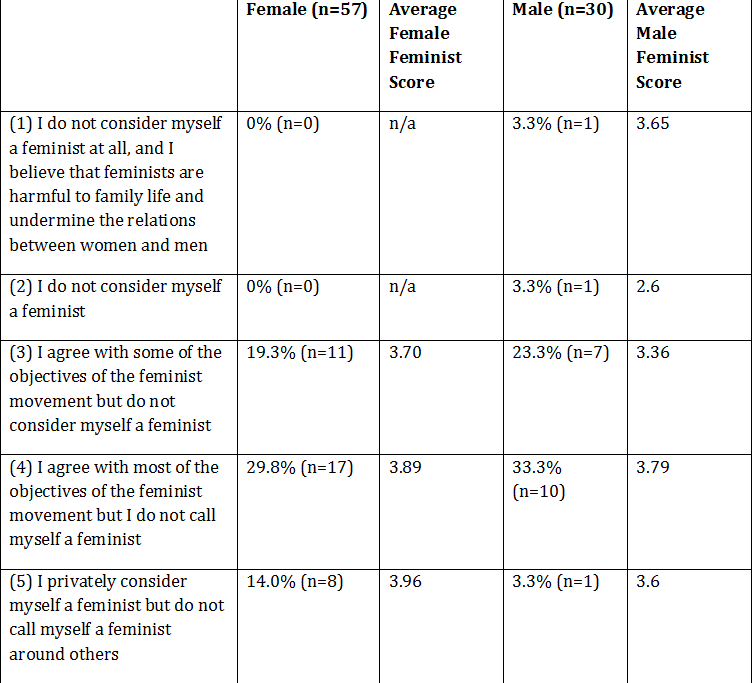

On average women (mean =4.01 and standard deviation =0.38) had significantly higher feminist scores than men (mean =3.73 and standard deviation =0.42). This was reflected in feminist identification, with a higher percentage of women than men identifying themselves as feminists, either publically or privately (numbers 6 and 7 on Myaskovsky and Wittig’s (1997) feminist identification scale). Of the male sample 36.7% (n=11) were willing to publically or privately identify themselves as feminist, compared to 50.9% (n=29) of the female sample. The most popular choice of feminist identification for women was to call themselves a feminist around others (31.6%, n=18), closely followed by those agreeing with most of the objectives of the feminist movement, but not identifying as a feminist (29.8%, n=17). For the male sample the most popular choice of feminist identification was those who agreed with most of the objectives of the feminist movement, but did not identify as a feminist (33.3%, n=10), followed by those who would call themselves a feminist around others (30%, n=9). No females identified themselves under the categories “I do not consider myself a feminist at all, and I believe that feminists are harmful to family life and undermine the relations between men and women” or “I do not consider myself a feminist” (numbers 1 and 2 on Myaskovsky and Wittig’s scale). Both categories received one male who identified as such. These categories, along with number 5: “I privately consider myself a feminist”, and number 7: “I call myself a feminist around others and am currently active in the women’s movement”, received one male vote making them the least popular categories for men. It should be noted that the male who identified himself as believing that feminists are harmful to family life received a feminist score of 3.65, which is as high as scores received by some who openly identified themselves as a feminist (this ranged from 3.65 to 4.75). The descriptive statistics discussed so far can be viewed in Table 1.

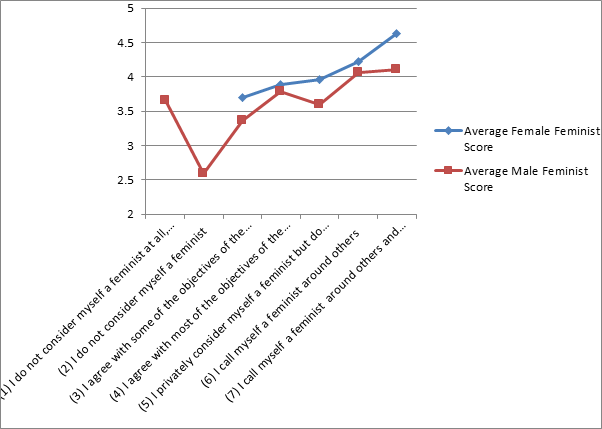

Given the above it can be identified that for the male sample, although there was a positive correlation between feminist identification from Myaskovsky and Wittig’s (1997) measure and feminist score, it was not strong in the same way as the female correlation. This can be seen through the calculation of the Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient’s, on which the male sample scored 0.68 and the female sample scored 0.96. From this it can be identified that for the male sample there is a moderate correlation between strength of personal feminist identification and feminist score, whilst for the female sample these two factors are very highly correlated. A visual representation of this can be seen in Graph 1.

Graph 1: A line graph showing the relationship between feminist identification (as measured on Myaskovsky and Wittig’s (1997) scale) and feminist scores for both men and women

Table 1: Table showing the number of females and males who identified as each category of Myaskovsky and Wittig’s (1997) feminist identification scale and the corresponding average feminist score

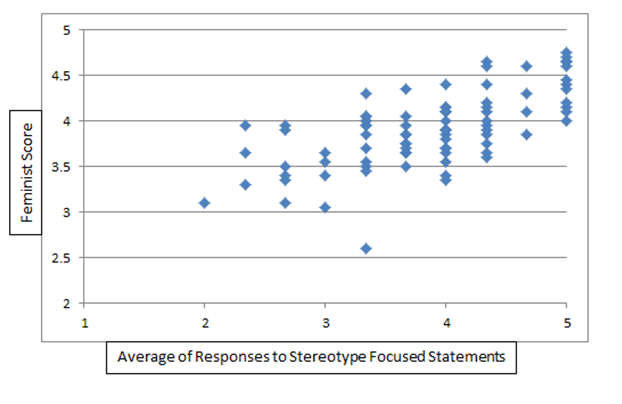

In the questionnaire there were three statements that directly addressed feminist stereotypes. These were: feminist women are more aggressive than non-feminist women; feminists are less attractive than non-feminists; men who identify as feminists are more likely to be gay. An average of participants’ responses to these statements was calculated and higher scores indicated that they did not subscribe to the negative feminist stereotypes. These averages were then plotted against their feminist score and a positive correlation was seen. A visual representation of this can be seen in Graph 2. The Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient score for these variables was 0.67 indicating that there is a moderate positive correlation between participants responses to stereotype focused statements and their feminist scores (generally the higher an individual’s feminist scores the less they subscribed to the negative feminist stereotypes examined in the three aforementioned statements).

Graph 2: Scatter graph showing the relationship between participants’ feminist scores and the average of their responses to stereotype focused statements.

Additionally Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient scores were calculated for the individual stereotype statements. There was a moderate positive correlation between feminist scores and participants responses to the statements “feminist women are more aggressive than non-feminist women” (Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient = 0.63) and “feminists are less attractive than non-feminists” (Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient = 0.55). A weak positive correlation was identified between participants response to the statement “men who identify as feminists are more likely to be gay” and their feminist scores (Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient = 0.33).

5.2 Focus Groups

Due to logistical factors of not having enough individuals willing to participate, and coordinating enough people in one location at a set time, only one focus group was held. It was comprised of seven people, three men and four women and lasted 30 minutes.

Analysis of the focus group data revealed three overarching key themes that influence an individuals’ reluctance to identify as a feminist: a misunderstanding of feminism, negative stereotypes, and complacency. These will be identified in the following section, giving note to numerous sub categories within the main themes. All quotes used within this section of this project are direct quotes from the focus group recordings.

5.2.1 Misunderstanding of Feminism

5.2.1.1 Only for the Benefit of Women

Participants discussed their belief that feminism is not about equality for both genders, but is instead only interested in the bettering of the position of females within society. It was suggested that it is the word itself, feminist, that gives the impression that it is only pro-women. This was identified by one of the male participants as a key reason that feminism had a bad reputation, particularly among males.

5.2.1.2 Parameters

A theme that arose among the group was the notion that feminists “jump on everything”. Many felt that feminists felt the need to perceive many events within society through a victimised lens, even when it may not necessarily be the case. They group suggested that feminists “make everything about feminism”. This raised the issue of a lack of understanding of the parameters of feminism, as the group believed that feminists have motivations in all aspects of life, with no clear goals.

5.2.1.3 Feminist = Active Protestor

One of the participants voiced that although they acknowledged that there were aspects of society that need to be changed, it was not enough to motivate them to go and actively protest in the streets. This will be considered later when discussing the theme of complacency, but it led to a discussion in which it was identified that all of the members of the group believed that in order to openly identify oneself as a feminist one must be an active participant in feminist demonstrations and/or protests.

5.2.2 Negative Stereotypes

Participants identified feminists with a range of negative descriptions such as opinionated, entitled, loud, argumentative, defensive and confrontational. It was however raised by a member of the group, and acknowledged by others, that these were stereotypical adjectives that may not be attributed to all feminists. Despite this, the general consensus was that the aforementioned attributes were nevertheless common and identified as a necessity for feminists who wanted their opinions to be heard.

5.2.2.1 Shaming from Feminists

An issue raised by one of the females in the group, which was met with agreement from the other females, was the notion that as a woman one is pressured into identifying as a feminist. It was suggested that if a woman did not identify as a feminist it seemed like feminists shamed them, suggesting they “don’t care about women’s rights or having equality with men and [they’re] happy to just look after children”. The females of the group voiced resentment towards this attitude from feminists.

5.2.3 Complacency

Although the group acknowledged the benefits of feminism concerning inequality and injustices abroad, for example regarding FGM, there was a consensus that it was simply not needed in the UK. Within the group all the females stated that they were content with their status within society, having never directly felt any limitations to their aspirations due to their gender. Furthermore the comparative aspect of equality in the UK being greater than it was in the past was raised, and it was suggested that this has now plateaued.

5.2.4.1 Inevitability of Inequality

There was a consensus within the group that the notion of gender equality is realistically unachievable. It was discussed that although it is good for society to reach a point where inequalities are minimal, ultimately “we are all different [and] we can’t pretend we’re all the same”. This notion was discussed within the framework of the role of the women as a mother and the male as the breadwinner.

5.2.4.1.1 Biological reasoning

Following the above notion of the inevitability of inequality a biological reasoning arose as a theme within the focus group. It should be noted that although not objected to by the males in the group, this section of the discussion was primarily female led. It was suggested that ultimately men and women are created for different purposes (i.e. women to carry and raise children), and as a result women are

more attached to nature, [they] carry children, [they] raise them, [they’re] better at that … certain things will never be completely equal, it just comes back to the fact that we are different and there will always be things that won’t be the same between men and women.

6. DISCUSSION

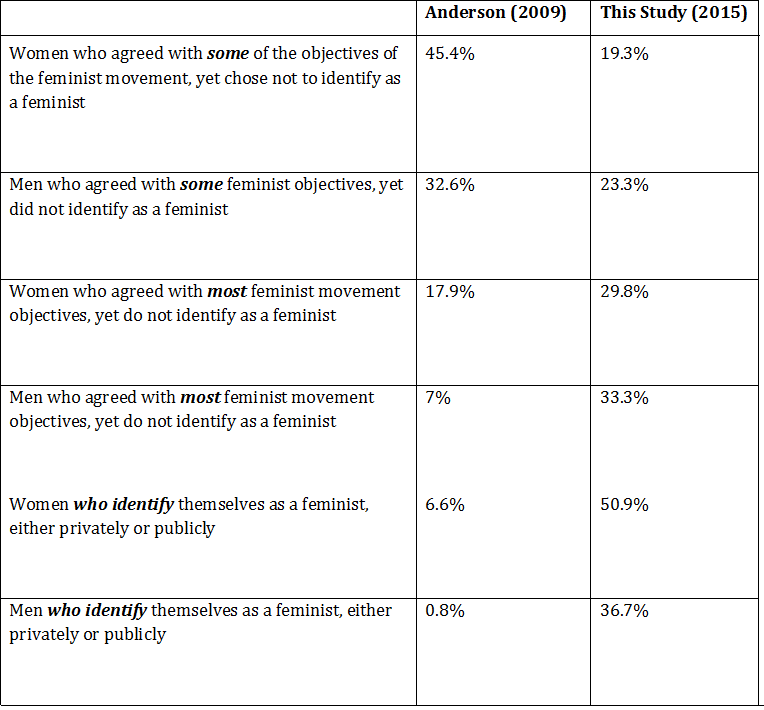

The structure of the questionnaire and quantitative aspects of this project has been developed from that of Anderson (2009), and thus it is interesting to compare some of the findings. The table below shows some of Anderson’s findings regarding feminist identification which were discussed in the literature review alongside some of the findings from this investigation.

Table 2: A table comparing Anderson’s (2009) feminist identification percentages to those found in this study

Given these results it can be seen that there has been a stark increase in feminist association for both genders: notably the final category of men who consider themselves feminists either publically or privately. In her study Anderson found only one man who identified as such, whereas in this investigation there were 11 men who were willing to do so. It should be noted that both Anderson’s study and this one were focused on university students. Furthermore, Anderson collected data from 404 participants, over four times as large as this projects’ sample of 87, and thus it would be expected that her sample would include a higher number of males identifying in these categories.

A study from Duncan (2010) which was discussed in the literature review may go some way in explaining this. Duncan (2010) found that the generation in which an individual is raised may affect their feminist identification. She identified that ‘baby boomers’ (born 1943-1960) who were young adults during the second wave of feminism had strong feminist identification. Contrastingly ‘Generation X-ers’ (born 1961-1975) who were young adults during the 1980s feminist backlash had weaker feminist identification. Therefore, perhaps the increase in association with the feminist label which has been found in this investigation compared to a study which was conducted six years earlier could be due to the idea that we are currently amidst a fourth wave of feminism. Scholars have been wary to suggest that we are in a fourth wave of feminism, as it is difficult to identify this without hindsight, but it has been speculated that this is currently occurring due to the surge of online feminist activism, using social media as a platform (Munro, 2013). It would be too bold to suggest that this data proves that we are in a fourth wave of feminism, but perhaps it could be considered an indicator of such a movement. Although this is an interesting point which has developed as a result of this research project, it is not the focus of this study which aims to gain an insight of factors that influence disassociation with the feminist label. Despite this, it is an unexpected and interesting finding that could be the focus of future research.

Furthermore, in analysing the questionnaire results it can be identified that men are more likely to disassociate with the feminist label than women. It was seen that on average women (mean =4.01 and standard deviation =0.38) had significantly higher feminist scores than men (mean =3.73 and standard deviation =0.42). This sentiment was reiterated in the participants’ personal feminist identification, with a higher percentage of women either publically or privately identifying themselves as feminists than men. Of the male sample 36.7% (n=11) were willing to publically or privately identify themselves as a feminist, compared to 50.9% (n=29) of the female sample. Moreover, the male Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient score of 0.68 indicates that although there is a moderate positive relationship between feminist identification and average feminist score, it is not as strong as the female correlation which scored 0.96. This implies that whilst for females there is a strong relationship between feminist score and personal feminist identification, and thus it can be expected that the higher a female’s feminist identification the higher their feminist score, this was not the case for men. Instead there is only a moderate correlation to suggest that females were better at identifying a personal feminist identification that is more in sync with their attitudes to feminist issues than men. This could otherwise be interpreted that men are more likely than women to disassociate with the feminist label, even when they agree with the objectives of the feminist movement. This can particularly be noted from the one male respondent who identified himself as believing that feminists are harmful to family life yet received a feminist score of 3.65, which is as high as scores received by some who openly identified themselves as a feminist.

Qualitative data from the focus groups revealed three key themes that can be factors that influence an individual to disassociate with the feminist label despite agreeing with the objectives. These were identified in the results chapter of this project as a misunderstanding of feminism, negative stereotypes, and complacency. The aforementioned male disassociation with the feminist label was also raised during the focus groups, falling under the identified theme of misunderstanding feminism. One participant questioned “can men be feminists?”. It was raised in conjunction with the thought that the feminist movement is about female empowerment beyond that of men, and thus it was suggested men can not be feminists. Although this was not considered the general consensus, it led the discussion to identify other factors which may put men off from identifying as feminists. The primary reason recognised was the female-centric nature of the word feminism: “the word itself makes it seem like it’s just pro women. For a lot of people, especially men, that’s why it can get a bad rep”. Moreover, other subcategories to the theme of misunderstanding feminism were identified. These were recognized as unknowing lack of knowledge concerning the parameters of issues which feminism addresses, and the belief that to identify oneself as a feminist one must be actively participating in protests or demonstrations.

Given the literature discussed in the literature review of this project, it was expected to find that negative stereotypes would be the primary influential factor behind disassociation with the feminist label, despite an individual’s attitudes to feminist objectives. Although this was identified as a key theme, it was not recognized to be more influential than other factors. Instead a misunderstanding of feminism seemed to be the most dominant theme that occurred, manifesting in a variety of ways.

Negative stereotypes did arise as an issue however and should not be overlooked, with descriptors such as opinionated, entitled, loud, argumentative, defensive and confrontational being used in relation to feminists. It should be noted that it was acknowledged by the group that such traits were stereotypes which may not necessarily be universally applied to all feminists, but there was the general feeling that they were nevertheless common among feminists. The questionnaire proposed three statements which were established in relation to previous research by Anderson (2009) and Twenge and Zucker (1999) that focused on such negative stereotypes, which were as follows: feminist women are more aggressive than non-feminist women; feminists are less attractive than non-feminists; men who identify as feminists are more likely to be gay. It was identified that there was a moderate positive Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient score of 0.67 between the participants’ feminist scores and an average of their responses to the stereotype focused statements. Additionally Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient scores were calculated for the individual stereotype statements correlation with participants’ feminist scores. They were identified as the following: “feminist women are more aggressive than non-feminist women” (Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient = 0.63); “feminists are less attractive than non-feminists” (Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient = 0.55); “men who identify as feminists are more likely to be gay” (Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient = 0.33). Given this, these statistics would suggest that a person’s feminist score may not be an indicator of their responses to negative feminist stereotypes and furthermore, this may also indicate that even those with high feminist scores may be influenced by negative stereotypes.

The final theme that was identified in the focus groups as an influencing factor behind disassociation with the feminist label was the notion of complacency. It was raised that although the group understood the need for feminism in circumstances of severe inequality, the backgrounds of the participants had never left them feeling marginalised enough to feel the need to identify as a feminist. There was the general consensus that the need for feminism in the UK had plateaued and any residual inequality in society was ultimately inevitable. Such sentiments were supported by the belief that ultimately men and women are biologically created differently and thus it would be impossible to achieve complete equality. It should be noted that this part of the discussion was primarily female led.

6.1 Strengths and Limitations

A significant limitation to this investigation is the small sample size to the focus group section of the research. This section was the primary source of data that directly addressed the research question. However, given that only one focus group consisting of seven participants was conducted, findings can not be considered reliable as there was no opportunity to identify consistently occurring themes over a number of groups. Furthermore, the sample used in this study was only University of Kent students, and thus the sample was limited to people all partaking in higher education that would perhaps be more aware of feminism and the objectives of the movements. Including participants from a wider variety of educational and socio-economic backgrounds would result in more inclusive findings.

The questionnaire section of the research however did receive a more notable sample size of 95 respondents, of which 87 data sets were usable once the data was cleaned, and from which valuable quantitative data was collected. Although not directly focused on the research question, which was heavily reliant on the qualitative data, questionnaire responses enabled the project to test H2 and H3, and given the sample size there is a higher degree of validity and reliability to these findings.

Furthermore, the use of both quantitative and qualitative methods for this research can be considered a strength. The mixture of methods gives a diverse perspective on the question at hand, enabling a thorough investigation.

6.2 Recommendations for Future Research

This discussion has identified the unexpected finding of a stark increase of association with the feminist label from both men and women in this study compared to the findings from Anderson (2009). I have postulated within the framework of research conducted by Duncan (2010) and Munro (2013) that this could be an indicator that we are currently in a fourth wave of feminism, but I have recognised the limitations of such suggestions. Perhaps further research focused on this area could be conducted to give insight into this concept which has yet to be investigated.

Furthermore, a major limitation to this study, which has been identified is the small number of people who ultimately took part in the focus groups. If this study were to be conducted again it would benefit significantly from an increased initial sample size, which one would expect would in turn increase the number of people meeting focus group conditions and who consent to taking part in them. Furthermore it would be beneficial to allocate more time for the organization of the focus groups, perhaps offering more options of days on which individuals could participate, as it was primarily logistical factors that prevented some of the willing participants from partaking in the focus groups.

CONCLUSIONS

This research project has never claimed to seek one reason as to why an individual may not identify with the feminist label despite agreeing with feminist ideals, but instead it has endeavoured to shed light on some of the factors which may influence an individual to do so. In seeking to explore the research question, “what are the primary factors that influence University of Kent students who agree with the objectives of the feminist movement to disassociate with the feminist label?”, this investigation has tested three hypotheses.

Given the findings, this investigation has rejected hypothesis one and accepted the null, in that it was found that negative feminist stereotypes are not the primary influence on disassociation with the feminist label for University of Kent students who agree with the objectives of the feminist but do not identify as feminists. Although this study did identify that negative feminist stereotypes are an influential issue in disassociation with the feminist label, it is not the primary factor. Instead a misunderstanding of feminism is identified as the most influential factor, with the notion of complacency also being a factor to be considered.

Hypothesis two was accepted, and the null was rejected, as it was found that men are more likely to disassociate with the feminist label despite agreeing with the objectives of the feminist movement than women.

Finally, hypothesis three was accepted and the null was rejected, as it was identified that there was an increased percentage of individuals openly identifying as a feminist than that seen in research by Anderson (2009).

REFERENCES

Anderson, V. (2009). What’s in a Label? Judgements of Feminist Men and Feminist Women. Psychology of Women Quarterly 2009 33: 206. http://pwq.sagepub.com/content/33/2/206 [Accessed 01/04/2015]

Breen, A. B., & Karpinski, A. (2008). What’s in a name? Two approaches to evaluating the label feminist. Sex Roles, 58, 299–310.

Duncan, L. (2010). Women’s relationships to feminism: Effects of generation and feminist self-labelling. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34 (2010), 498–507.

Edley, N., & Wetherell, M. (2001). Jekyll and Hyde: Men’s constructions of feminism and feminists. Feminism and Psychology, 11, 439–457.

HeForShe. (2015). Home – Heforshe. http://www.heforshe.org/ [Accessed 11/04/2015]

Munro, E. (2013). Feminism: A Fourth Wave? Political Studies Association. http://www.psa.ac.uk/insight-plus/feminism-fourth-wave [Accessed 07/04/2015]

Myaskovsky, L., & Wittig, M. A. (1997). Predictors of feminist social identity among college women. Sex Roles, 37, 861–883.

O’Leary, Z. (2005). Researching Real-World Problems: A guide to methods of inquiry. London: Sage Publications.

Prati, F., M. Vasilijevic, R. Crisp and M, Rubini. (2015). Some extended psychological benefits of challenging social stereotypes: Decreased dehumanization and a reduced reliance on heuristic thinking. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. http://gpi.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/02/25/1368430214567762.full.pdf+html [Accessed 09/04/2015]

Ritchie, J. (2014). Qualitative Research Practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Ruane, J. (2005). Essentials of Research Methods: A guide to social science research. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Stewart, A. J., & Healy, J. M., Jr. (1989). Linking individual development and social changes. American Psychologist, 44, 30–42.

Twenge, J. M., & Zucker, A. N. (1999).What is a feminist? Closed and open-ended responses. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23, 591–605.

Steele, C., S. Spencer and J, Aronson. (2002). Contending With Group Image: The psychology of group stereotype and social identity threat. Advances in social psychology. Vol 34, p 379-440. New York: Academic Press.

Un.org. (2015). Gender Equality For Women Benefits Men Too, Deputy Secretary-General Tells Barbershop Conference, Urging Stronger Role In Transformational Changes | Meetings Coverage And Press Releases. http://www.un.org/press/en/2015/dsgsm837.doc.htm [Accessed 10/04/2015]

Whitworth, S. (2008) ‘Feminist Perspectives’ in Williams, P. (2008) Security Studies: An Introduction London and New York: Routledge pp. 103-115

APPENDIX 1 – Questionnaire Briefing

APPENDIX 2 – Questionnaire

APPENDIX 3 – Focus Group Questions

- What comes to mind when you hear the word feminist?

- What factors make you shy away from calling yourself a feminist?

- Do you believe that feminism holds negative stereotypes?

- Do you believe feminism is about equality?

- What is your perspective on other social movements for equality, i.e. race and sexuality?

- Do you think there has been an increase in feminist activity in recent years?

- Is there a need for feminism in modern society?

Written by: Katherine Remenyi

Written at: University Of Kent

Written for: Iain McKenzie

Date written: 04/2015

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Protection Paradox: Why Security’s Focus on the State Is Not Enough

- Why Are Feminist Theorists in International Relations so Critical of UNSCR 1325?

- South Korea Is Not In Democratic Backslide (Yet)

- Emancipation and Epistemological Hierarchy: Why Research Methods Are Always Political

- Rojava’s Patriarchal Liberation: Solving the Feminist Anti-Militarism Problem?

- Limits of Liberal Feminist Peacebuilding in the Occupied Palestinian Territory