The Islamic State (IS) has carried out many attacks worldwide since declaring that it was restoring the Caliphate in 2014. Attacks such as swarming attacks (where multiple attackers target from multiple sides, or multiple locations using guns and bombs), vehicle ramming attacks, and suicide bombings have been widely used by the group. Many of these attacks have targeted the West, but some have also targeted predominantly Muslim countries targeting both Muslims, and Christians; these include attacks such as the 2015 Bardo National Museum attack in Tunis, Tunisia, the Riu hotel attack in Sousse, Tunisia, the May 2017 bus massacre in Egypt, and the recent attack on tourists in Hurghada, Egypt in July, 2017. On June 7, 2017 a swarming attack occurred in Tehran, Iran targeting the Iranian Parliament building and the mausoleum of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, by two groups of armed assailants. This attack was claimed by the Islamic State, and would be the first successful attack carried out in Iran by the group. Was this attack similar to the ones ISIS has carried out throughout Europe? How does this attack fit into the goal of the Islamic State, and what are the possible outcomes after this attack? This article will give a brief background on the Islamic State, and provide an analysis of the June 7th attack in Iran and how it was the same or different from the Islamic State’s other attacks in the EU.

The Rise of al-Zarqawi and the Islamic State

The history of the Islamic State can be traced back to Iraq in the mid-2000s. McCants (2015) recounts the birth of the Islamic State as a group whose genesis was started by Jordanian jihadist Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi. Zarqawi had traveled to Afghanistan twice, once in 1989 and a second time in 1999. During his first visit to Afghanistan, Zarqawi was introduced to Sheikh Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, a Salafist cleric. According to Weaver (2006), Zarqawi embraced Salafism and adopted Maqdisi’s hatred for the Shi’a. In 1993, Zarqawi and Maqdisi left Afghanistan for Jordan and traveled around Jordan preaching and recruiting jihadists. Later, they were both arrested for possession of hand grenades and sentenced to prison. They were released from prison in May 1999, following the declaration of a general amnesty by Jordan’s newly enthroned King Abdullah II.

In December 1999, Zarqawi went to Kandahar, Afghanistan, to seek support of al-Qaeda, in setting up a training camp. Zarqawi met with, but failed to impress Osama bin Laden. Zarqawi’s professed hatred on the Shi’a was potentially one of several divisive issues (bin Laden’s mother is a Shiite). However, Zarqawi was funded and he established a training camp in Herat, Afghanistan. Weaver (2006) estimated the camp size as 2,000 to 3,000 jihadists and family members.

Following the 2002 invasion of Afghanistan by the US and the fall of the Taliban, Zarqawi fled to Iraq, by way of Iran. Once in Iraq, Zarqawi established his clandestine network, Jama’at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad (English: Organization of Monotheism and Jihad). Zarqawi’s group claimed responsibility for the August 7th bombing of the Jordanian embassy and the August 19th bombing of the UN headquarters in Baghdad, as well as the August 29th, 2003 bombing of the Shi’a shrine in Najaf, the mosque of Imam Ali. This deadly bombing killed over 100 people, to include cleric Ayatollah Muhammad Baqr al-Hakim. Zarqawi had assistance in these attacks from former security officers in Saddam Hussein’s government, who were purged from office, following the US invasion of Iraq.

McCants (2015) identified Zarqawi’s plan in Iraq as being focused on provoking the Shi’a. By continually attacking the Shi’a, Zarqawi believed that the Shi’a would be forced to engage the jihadists in battle. By provoking the Shi’a into battle in Iraq, the resulting fight would force Sunnis to take the side of the jihadists against Iran and the US. Zarqawi offered his allegiance to al-Qaeda, on condition that they would accept his plan. Despite reservations, in October 2004 al-Qaeda accepted Zarqawi’s oath, and al-Qaeda in Iraq was born.

Zarqawi expressed a desire to form a caliphate in Iraq. Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri, al-Qaeda second-in-command at the time, warned him to wait until he had the support of the Sunni masses. Zarqawi’s actions were not winning Sunni support. Zarqawi became notorious for his videotaped beheadings. Zawahiri feared that Zarqawi would lose the support of Iraqi Sunnis with these tactics.

Burns (2006) reported that Zarqawi was killed in a US airstrike on an isolated safe house in Baqubah, north of Baghdad. McCants (2015) identified Zarqawi’s successor as Abu Ayyub al-Masri. In October 2006, Masri declared the formation of an Islamic State, and named Abu Umar al-Baghdadi as the “commander of the faithful.” The significance of this title (commander of the faithful), according to Pennell (2016), indicates either the caliphate or a level of authority beneath the caliphate. Al-Baghdadi was a complete unknown in the jihadist world. McCants (2015) stated that this announcement caught Zawahiri and bin Laden totally by surprise.

The Islamic State was not a real state, as it was unable to supply those functions expected of governance. The members of the Islamic State, however, operated with extreme brutality against other Sunni militant groups. According to Lewis (2013), in early 2007, the Islamic State was responsible for the deaths of approximately 2,500 civilians per month. By 2008, this number dropped to 500 per month. Masri and al-Baghdadi’s control of the Islamic State was ended in April 2010, when both were killed during a joint US and Iraqi forces raid. McCants (2015) reported that the Islamic State then named Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim Ali al-Badri as the next “commander of the faithful.” Despite Ibrahim being Sunni, he claimed descent from the tenth imam, and through him, Ibrahim traced his lineage to the first imam, Ali.

Upon his selection as “commander of the faithful,” Ibrahim chose the nom de guerre of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. McCants (2015) advised that following the death of bin Laden, Baghdadi made a public statement that the Islamic State was faithful to al-Zawahiri and al-Qaeda. At that time the announced departure of the US military from Iraq was an opportunity for the Islamic State to grow. The Islamic State targeted Iraqi military and Iraqi police.

According to McCants (2015), the expansion of the Islamic State into Syria was a result of President Bashar al-Assad’s release of an unknown number of jihadists from prison. Assad planned that this release would foster violence among the protestors of his regime. This would allow him to crack down on protestors. In response to the violence against the protestors, Zawahiri ordered the Islamic State to send a group to Syria. The Islamic State battled rival rebel groups for the city of Raqqa in northern Syria, until they captured it on January 14, 2014.

Jabhat al-Nusra, led by Abu Muhammad al-Jawlani, became al-Qaeda’s affiliated group in Syria. The Islamic State and al-Nusra clashed over their approach in dealing with Syrian locals and rebel groups. The Islamic State dealt with rebel groups with strict Shari’a law and violence; al-Nusra collaborated with other rebel groups. This led to Zawahiri and Baghdadi clashing over conflicts between the two groups. Finally, in February 2014, al-Qaeda removed the Islamic State as an affiliated group. This separation was complete with the suicide bombing attack by Islamic State martyrs against al-Qaeda representative Abu Khalid.

Following this schism, the Islamic State secured eastern Syria, to include its oil fields. Many of the al-Nusra fighters, and other rebel groups joined the Islamic State. Recruits from around the world flocked to fight under the black banner of the Islamic State. Belief in an apocalyptic battle between Muslims and non believers caused the Islamic State to fight for the strategically insignificant border town of Dabiq. The Islamic State produced an online English language magazine, Dabiq, to aid in recruiting funds and fighters.

A report by Public Radio International (2017) provides the following changes in Islamic State’s territorial holdings: in June 2014, the Islamic State started an offensive in northwestern Iraq, in which the city of Mosul was seized. This forced Christian and Yazidi sects to flee. In response to requests from the Iraqi government, the US conducted airstrikes against Islamic State positions in northern Iraq in August 2014. The Islamic State captured Tikrit at the end of March 2015, which was recaptured by Iraqi forces in June 2015. In November 2015, Iraqi Kurds recaptured the northern Sinjar region. In February 2016, the Sunni town of Ramadi was recaptured from Islamic State. In June 2016, Fallujah was recaptured by Iraqi forces.

Likewise, the Islamic State was being forced out of Syria: January 2015, Islamic State is forced out of Kobane, August 2016, forced out of Manbij, and October 2016, forced out of Dabiq. This led to renewed calls from the Islamic State for operatives worldwide to target in the countries they were in. The Islamic State launched terror attacks against the West and Russia, to include the October 31, 2015 bombing of Russian Metro Flight 9268 in Egypt, the multiple venue attacks in Paris on November 13, 2015, and the Brussels airport and subway attacks on March 22, 2016. Additionally, Islamic State-inspired jihadists conducted multiple attacks.

The Islamic State has been pushed into smaller and smaller territorial possessions in Syria and Iraq. Baghdadi has been reported as having been killed in air strikes at the end of May 2017, however, this has not been confirmed yet. The more ground the Islamic State is losing in Iraq and Syria, the more attacks they seem to be perpetrating in other countries.

Attack in Iran

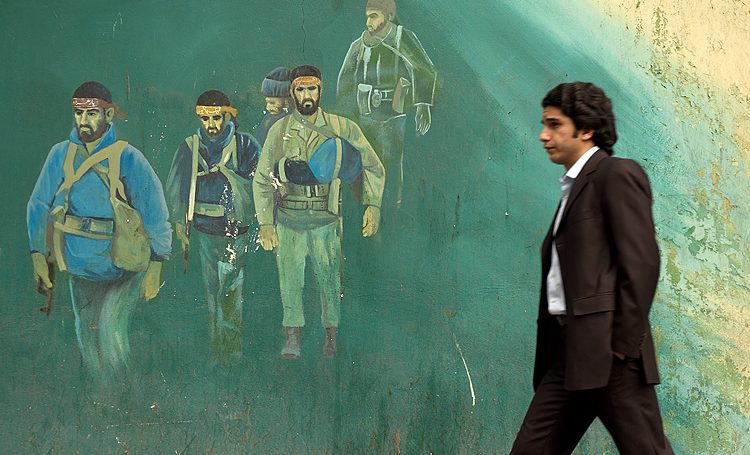

Although there have been no previous attacks by the Islamic State in Iran, Iranians have long been targeted by groups in the area. In Iraq, for example, there have been numerous bombings targeting Iranian Shia making pilgrimages to Karbala. Shia’s were also a target in Iraq during the Saddam Hussein regime, prior to Operation Desert Storm in 1991. Even after Nouri al-Maliki became Prime Minister in Iraq in 2006, there were tensions on his reliance on Shia militiamen to fight against ISIS in Iraq (Stern & Berger, 2015). These groups were believed to be closely aligned with Tehran, more than they were with Baghdad (Stern & Berger, 2015). Even after the fall of Mosul, the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) was created after a fatwa[1] was issued by the Shia Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani (Watling, 2016). Al-Sistani stated that fighting against the Islamic State was “a sacred defense” and those who would defend their country would be a martyr (Watling, 2016).

The most recent attack carried out by a Sunni group in Iran was in 2010; a twin suicide bombing targeting Shia worshippers outside a mosque in Iraq carried out by Jundullah. In 2016, however, Iran thwarted a series of planned attacks targeting Tehran to take place during the Ramadan holidays. According to Iran’s Tasmin news agency, the Iranian military is assisting Syrian commanders, as well as providing weapons, operational support, and assisting with strategic planning in the battle against the Islamic State, as well as an estimated thousand Iranians on-ground in Syria (Armstrong, 2016). Iran has also provided help fighting ISIS in Iraq. This, coupled with the fact that Iran is primarily a Shia country, creates a target on their back.

Nearly a year after the planned attacks on Tehran were foiled, a near simultaneous terrorist attack was committed in Tehran on June 7th, 2017. The two attacks targeted the Iranian Parliament and the tomb of Ayatollah Khomeini, and were carried out using guns and suicide bombers; a third attack was allegedly foiled according to the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence (Bozorgmehr & Dewan, 2017). The attacks left 17 dead and at least 50 wounded (O’Connor, 2017). Dozens have been arrested in connection with the bombings. The Islamic State claimed responsibility through their Amaq News channel via a video recorded in Arabic and Kurdish (Erdbrink, 2017). The message stated that the “brigade” of the Islamic State had carried out the attack in Iran, and would continue to carry out attacks there in the future as well. Iran believes that those responsible for the attacks in Tehran were Iranians who fought in Iraq and Syria and had returned to Iran (O’Connor, 2017).

The attacks in Tehran were nearly simultaneous attacks which are similar to the method used by the Islamic State to carry out attacks in Paris, and other cities in Europe. Several attackers entered each venue with guns and bombs which is also reminiscent of some of the Islamic State attacks carried out in Europe. The Islamic State claimed the attacks fairly quickly as was the case in many of their attacks throughout Europe. In the claim, the Islamic State also called for more attacks to occur in Iran, which is similar to statements made shortly after their attacks in Europe as well. Since the attackers are believed to have fought in Syria and Iraq before returning to Iran, there is naturally a concern about the threat posed by returnees from those conflict areas, not just in Iran, but in European countries as well.

The Future?

The Islamic State has focused on the Shi’a as the main enemy, from its inception to the present date. Zarqawi’s conversion to Salafism solidified his hatred of the Shi’a. Mamouri (2015) stated “… radical Salafists consider both Shiites and Jews the enemy of Islam.” Zarqawi’s 2003 bombing of the mosque of Imam Ali is just one example of this hatred. Zarqawi’s group had carried out many attacks not only against Shia in Iraq, but particularly targeting Iranian pilgrims in Karbala. Over the past several years, the war in Syria has increased the sectarian violence and had therefore only served to widen the divide between the two.

The attempted attack in Tehran during Ramadan in 2016 was believed to be an attack that was planned by the Islamic State. Their second attempt, just a year later, was successful. Since the availability of guns in Iran is tightly controlled, it is believed that the weapons for the Tehran attack were brought from outside the country (Bozorgmehr & Dewan, 2017). If this is the case, there may be a terror network that is operational inside, and outside Iran, which may point to further attacks being attempted in Iran in the future. The attack in Iran may also serve to increase tensions in the already volatile Middle East.

Notes

[1] A ruling or decree issued by a recognized Islamic authority or scholar.

References

Armstrong, P. (2016, June 20) Iran: ‘Ramadan Terror Plot’ on Tehran Foiled. CNN.

A timeline of the Islamic State’s gains and losses in Iraq and Syria (2017 February 19). PRI.

Bozorgmehr, S. & Dewan, A. (2017, June 7). ISIS Claims Attacks on Iran’s Parliament and Shrine, 12 Killed. The CNN Wire.

Burns, J.F. (2006, June 8). U.S. Strike Hits Insurgent at Safehouse. The New York Times.

Erdbrink, T. (2017, June 9). Iranian Kurds Are Implicated in Terrorist Attacks in Tehran. The New York Times.

Erdbrink, T. & Mashal, M. (2017, June 7). At least 12 killed in pair of terrorist attacks in Iran. The New York Times.

IS Claims through ‘Amaq its first attack in Iran (2017, June 7). Site Intelligence Group.

Lewis, J.D. (2013). “Al-Qaeda in Iraq Resurgent: The Breaking the Walls Campaign, Part I,” Institute for the Study of War, Middle East Security Report 14 (September, 2013): 8.

Mamouri, A. (2015, February 11). Why Salafists see Shiites as their greatest enemy. Al Monitor: the Pulse of the Middle East.

McCants, W. (2015). ISIS apocalypse: the history, strategy, and doomsday vision of the Islamic state. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

O’Connor, T. (2017, June 8). ISIS Militants Plotted Tehran Attacks for a Year, Fought in Iraq and Syria, Iran Says. Newsweek.

Pennell, Richard (11 March 2016). “What is the significance of the title ‘Amīr al-mu’minīn?'” The Journal of North African Studies. 21 (4): 623–644. doi:10.1080/13629387.2016.1157482

Stern, J. & Berger, J.M. (2015). ISIS: The State of Terror. New York: Harper-Collins

Watling, J. (2016). The Shia Militias of Iraq. The Atlantic, December 22, 2016.

Weaver, M.A. (2006). The short, violent life of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. The Atlantic, July/August, 2006.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- International Relations Theory and the ‘Islamic State’

- Violent Non-State Actors in the Middle East: Origins and Goals

- Islamic State Men and Women Must be Treated the Same

- The Separability of Jihad

- If There Was a Time to Support Reformists in Iran, It’s Now

- 5 Reasons Why the West Got Islamist Terrorism Wrong