The 2008 US Presidential Elections was a watershed in American politics which culminated with Barack Obama being sworn in as the nation’s first African-American president. Being a relatively untested candidate in the political scene as compared to his more seasoned opponents such as Hilary Clinton and John McCain, Obama’s presidential campaign had to convince voters that he was the best choice to deal with the myriad of problems facing America despite his lack of experience in public office. The “Progress” poster by street artist Shepard Fairey could be said to be an important medium in which the message and ideals of Barack Obama could be instantly transmitted to the public. It is a powerful visual icon that has achieved pop culture status with variations of the image being emblazoned on clothes, stickers and other paraphernalia, affirming the cliché that images have a certain “social or psychological power of their own”.[1] This paper will attempt to examine how the “Progress” poster relates to its political meaning by looking in depth into different aspects of the image and then consider the consequences of this image on the election campaign and presidency of Barack Obama.

The “Progress” Poster and the 2008 US Presidential Elections

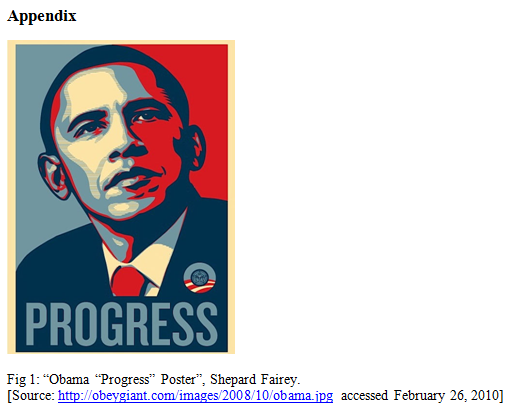

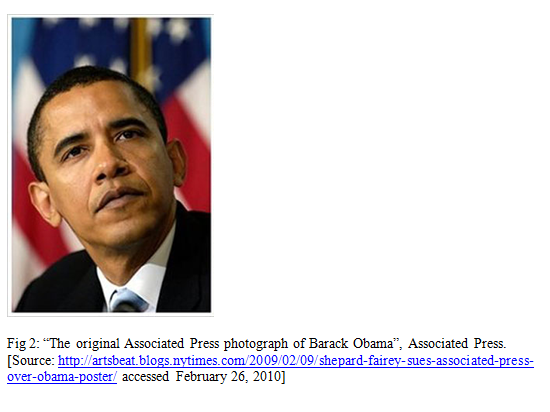

The image is an 85x55cm screen-print of Barack Obama above the word “Progress” (Fig.1). Another variant of the same image with the word “Hope” now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, cementing the image’s role “an emblem of a significant election, as well as a new presidency” as mentioned by Martin E. Sullivan, director of the National Portrait Gallery.[2] The poster is simple in its imagery, showing only Obama’s upturned face on a red, white and blue field, inviting the viewer to link Obama with the rhetoric of “progress” for America. The image itself was lifted from a photograph from the Associated Press taken of Barack Obama at the National Press Club in 2006 (Fig. 2). The resulting lawsuits and counter lawsuits between Fairey and the photographer, as well as its mundane inspirational origins, seems to run contrary to the messages of ‘progress’ and ‘hope’ and deflates the idea of Obama as a visionary and saviour.[3] Nonetheless, the image itself remains an interesting example of political symbolism and how imagery can be an effective tool to be yielded in a national election.

Election campaigns are highly visual events with millions of dollars spent by candidates to improve their image to the electorate. While the use of imagery is not new in politics, visual images are especially important in democracies where the perception of candidates go a long way towards shaping voter reaction. As Hacker points out, election campaigns are more about the candidates and how they portray themselves as the best person to deal with issues and less about the issues per se.[4] Hence, visual tools such as political posters play an important role in providing cues about a candidate’s political ideology – the set of beliefs that “presents a social order as if it were a natural order”.[5] Studies have shown this by confirming that political advertising do have an effect on the image of a candidate.[6] For a political unknown like Obama, visual cues are especially important in his campaign for presenting his ideas to the American public. This poster would hence allow supporters of Obama to coalesce around a symbol. Another advantage of political posters is that they remind the voter of a variety of characteristics and attributes of the candidate that would make him or her the most suitable candidate, proving true that adage that “a picture is worth a thousand words”.[7] When an object such as a political poster gains enough prominence so that it can “crowd out” other issues and considerations the audience would have, leaving only the message that the candidate wishes to impart.[8] Images also help shape public opinion by communicating what Hairman and Lucaites call “social knowledge”, deep seated beliefs about society held by members of the public.[9] The “social knowledge” here would be that anyone can be President of the United States, and the colour of Obama’s skin should be no barrier to running for the highest office in the land. The “Progress” poster fulfills all of this by utilising several visual approaches which will be discussed below.

Visual Analysis of the “Progress” Poster

The medium of the visual image is in itself telling. It is a poster, something that is easily available to the mass public as opposed to artwork displayed in offices, museums or galleries.[10] A political poster would allow for maximum public outreach, and the use of the same image on other paraphernalia ensures that it is transmitted as widely across America as possible. As Fairey stated in an interview with the Huffington Post,

I think what then happened was that there were a lot of people who were digging Obama but they didn’t have any way to symbolically show their support. Once there was an image that represented their support for Obama then that became their Facebook image or their email signature or something they use on their MySpace page. Or they printed out the image and made their own little sign that they taped up in their office. Once that exists it starts to perpetuate and it replicates itself.[11]

In other words, the image soon went viral. The fact that the image was created by Fairey, a street artist in America, also speaks volumes. The image was not commissioned by the Obama campaign and the original poster with its message of “Progress” was in fact frowned upon by the Obama campaign for sounding too “Marxist”.[12] It is, however, a testament to Obama’s popularity that such a project was undertaken out of Fairey’s own initiative. The use of street art is also significant in that street art is viewed as anti-establishment and “constitute a political counterattack against the traditional mode of artistic creation and distribution in Western culture”.[13] This would fit with Obama’s image as a politician who remains “outside the beltway”, someone who would change the way the politics was run in Washington. Lastly, street art is also an artistic form that resonates with the youth of America, one of Obama’s most supportive constituents.

The second aspect of the image that stands out is the colours used. This image is recognizably different from the usual red, black and beige that Fairey favours in his other prints.[14] Red, white and blue are colours that are instantly recognized as American and Fairey uses them to give a patriotic edge to his poster.[15] Hill argues that value of patriotism is intertwined with the image evoking the value and the emotions aroused by that value.[16] Once this association has been constructed in the minds of the viewers, the image becomes synonymous with the value of patriotism and can be used to trigger the accompanying emotions.[17] Hence political images remain powerful in the sense that they arouse in their viewers involuntary reactions about patriotism, not unlike how advertisements featuring children evoke feelings of sympathy in most people.[18] However, the colours of red and blue have also been used in connection with the Republican and Democratic Party respectively. By uniting the colours with white in between, Fairey paints Obama as someone who is above partisan politics, able to unite Americans especially in light of a bruising campaign dividing American into blue and red states. This echoes Obama’s own words at the 2004 Democratic National Convention where he calls for a “United States of America” instead of a liberal or conservative America, an America with blue and red states.[19] Obama reiterates the need for bipartisanship and unity in a nation divided in red and blue when he writes in The Audacity of Hope that Americans should not “paint [their] faces red or blue and cheer our side and boo their side… for winning is all that matters”.[20] Being the first African-American presidential candidate, Obama’s run for president was always dogged by the matter of race and his mixed parentage even raised cries of whether he was ‘black enough’.[21] The colours also render the matter of Obama’s skin colour as a non-issue. By portraying him in red, blue and white, it can be said that the artist makes Obama’s identity as an African American subordinate to his identity as an American. Nonetheless, the predominance of the colour blue clearly tells the viewer which party Obama belongs to. Reinforcing Obama as American was especially important given his upbringing outside of the United States and the resulting controversy over whether he was deemed “American” enough to be the Commander-in-Chief. Lastly, the simplicity of the image, as shown by the utilisation of only three colours and the bold lines, serve as a kind of visual enthymeme – arguments with gaps to be filled in by the participants or viewers.[22] Although the image makes no mention of Obama’s political rivals, it is no leap of the imagination to infer that “progress” would not be achieved by voting for them. Furthermore, there is no mention anywhere about what Obama is supposed to be the ‘hope’ of, or why ‘progress’ is needed. To any other viewer from another time or place, these may seem like any other campaign rhetoric and pretentious political promises made by any other presidential hopeful. However, when placed in the context of America in 2008, what the poster, and Obama, promises is especially appealing for voters. It is the hope that sons and daughters would soon come home safely from fighting wars in two parts of the world, and that progress would be achieved in areas such as healthcare, climate change and most of all, the economy. Any American who has kin in active combat or has just been retrenched or been denied healthcare due to insufficient insurance coverage would be able to relate to the message of the poster.

The other striking feature of this image is the gaze of the subject. Fairey chose a photograph of Obama that made him look “wise but not intimidating”.[23] Obama is painted gazing in the distance, giving one the impression of an optimistic future led by a farsighted leader. His expression is solemn and he appears to be deep in thought, undoubtedly because of the many troubles plaguing America. Yet he maintains a calm countenance and stoic acceptance of the fact, as befitting his nickname of “No Drama Obama”, and ponders the best way out for America. Indeed, by changing the subject’s gaze, numerous parodies of the poster have been created of Obama’s political rivals (Fig 3). Adding a squint to John McCain gives him a quizzical and puzzled expression and Sarah Palin with her open mouthed grin and wide-eyed stare is made to look comical and foolish. Utilising the same colour scheme as the original “Progress” poster allows the viewer to juxtapose in his or her mind the original image of Obama with the satirical images of McCain and Palin to reach an unflattering conclusion on the Republican candidates. The gaze has also led some to remark on the resemblance between Fairey’s poster and another iconic image – that of Che Guevara created by Jim Fitzpatrick (Fig 4).[24] Visual resemblance aside, both images represent a revolutionary ideal and a rejection of convention that appeals to the youth.

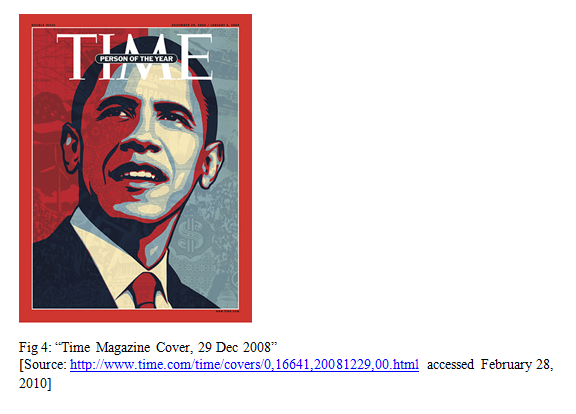

With the image emerging on the national consciousness and becoming an iconic representation of Barack Obama, it was almost inevitable that it would be adapted for other intents. Time Magazine commissioned Fairey in 2009 to produce a similar picture for its cover page honouring Barack Obama as the Person of the Year (Fig 4). While the resulting cover page is similar to the original image in terms of style and colours, Fairey embellished it with numerous issues such as the economy, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and climate change, all of which require much needed ‘progress’. Nonetheless, using such a conspicuous campaign image inevitably led to questions about the impartiality of the publication and whether Time Magazine was campaigning for Obama.[25]

Creating the Myth of Barack Obama

Besides drawing on national myths, political images also serve to create a myth of the candidate to present to the public as political images portray the candidate not as himself, but as an idealized version of himself. Strachan and Kendall go as far as to argue that political images often paint candidates with “mythical, larger-than-life qualities”, associating the values of the nation with the values of the candidate, so that by reflecting core American values such as freedom and equality, the candidate’s claim to political office is legitimized.[26] However, this begs the question of whether such a myth is sustainable after the election and the consequences of constructing this glorified image of the candidate.

With Obama winning the 2008 Presidential Elections with 52% of the popular vote, it could be said that the goal of Fairey in creating the image was accomplished. However, Obama has seen a turnaround in his political fortunes one year into his presidency with his approval rating dropping 18% since he first took office.[27] He has been besieged with opposition to his domestic policies, especially with healthcare reform, and now faces a resurgent conservative movement. While this reversal of fortunes may appear to have nothing to do with the “Progress” poster, I would suggest that by creating and perpetuating the ‘myth’ of Obama as a near messianic figure here to solve all of America’s woes, it has led to inevitable disappointment when his campaign promises fail to materialize. Indeed, public indignation was expressed at Obama’s Noble Peace Prize win in 2009 for making little progress, especially with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Obama’s skilful rhetoric and his ability to communicate a message of hope, change and progress has proven to be a proverbial double-edged sword.[28] While this message, as illustrated in the “Progress” poster, may have won him the White House, it has also raised the public’s expectations about the whole range of issues which Obama has to solve, as evident in the Time Magazine cover in Fig 4.

Conclusion

The “Progress” poster is arguably one of the most famous images of Obama. The image conveys a sense of serenity and optimism that would reverberate with Americans who were facing many difficulties and found Obama’s message of hope inspiring. Through the use of simple colours and bold lines, Fairey has created an iconic presentation of Obama that would rival Fitzpatrick’s representation of Che Guevara. However, by raising the hopes and expectations of the American people to fevered levels, the “Progress” poster has also set unrealistic demands on Obama to solve most, if not all, of America’s pressing problems.

[1] W. J. T. Mitchell, What do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 32.

[2] Martin E.Sullivan, comment on “NPG Acquires Shepard Fairey’s Portrait of Barack Obama,” The National Portrait Gallery Blog, comment posted January 7, 2009, http://face2face.si.edu/my_weblog/2009/01/npg-acquires-shepard-faireys-portrait-of-barack-obama.html (accessed February 26, 2010).

[3] Peter Schjeldahl, “Hope and Glory: A Shepard Fairey Moment,” The New Yorker, February 23, 2009, http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/artworld/2009/02/23/090223craw_artworld_schjeldahl?currentPage=1, (accessed February 26, 2010).

[4] Kenneth L. Hacker, “Introduction: The Importance of Candidate Images in Presidential Elections,” in Candidate Images in Presidential Elections, ed. Kenneth L. Hacker (Westport: Praeger, 1995), xiv.

[5] Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites, No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 9.

[6] Lynda Lee Kaid and Mike Chanslor, “Changing Candidate Images: The Effects of Political Advertising,” in Candidate Images in Presidential Elections, in ed. Kenneth L. Hacker (Westport: Praeger, 1995), 89.

[7] Kathleen E. Kendall and Scott C. Paine, “Political Images and Voting Decisions,” in Candidate Images in Presidential Elections, in ed. Kenneth L. Hacker (Westport: Praeger, 1995), 28.

[8] Charles A. Hill, “The Psychology of Rhetorical Images,” in Defining Visual Rhetorics, in ed. Charles A. Hill and Marguerite Helmers (Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004), 29.

[9] Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites, No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 10.

[10] Paul Von Blum, “New Visions, New Viewers, New Vehicles: Twentieth-Century Developments in North American Political Art,” Leonardo 26 (1993): 465.

[11] Ben Arnon, “How the Obama “Hope” Poster Reached a Tipping Point and Became a Cultural Phenomenon: An Interview with the Artist Shepard Fairey,” The Huffington Post, October 13, 2008, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ben-arnon/how-the-obama-hope-poster_b_133874.html, (accessed February 28, 2010).

[12] Jenna Wortham, “‘Obey’ Street Artist Churns Out ‘Hope’ for Obama,” Wired, September 21, 2008, http://www.wired.com/underwire/2008/09/poster-boy-shep/, (accessed February 27, 2010).

[13] Paul Von Blum, “New Visions, New Viewers, New Vehicles: Twentieth-Century Developments in North American Political Art,” Leonardo 26 (1993): 465.

[14] See http://obeygiant.com/fine-art for examples of work from Shepard Fairey.

[15] William Booth, “Street Artist Fairey Gives Obama a Line of Cred,” The Washington Post, May 18, 2008, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/artsandliving/style/features/2008/obama-poster-051808/graphic.html?sid=ST2008051602005, (accessed February 28, 2010).

[16] Charles A. Hill, “The Psychology of Rhetorical Images,” in Defining Visual Rhetorics, in ed. Charles A. Hill and Marguerite Helmers (Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004), 35.

[17] Ibid.

[18] J. Anthony Blair, “The Rhetoric of Visual Arguments,” in Defining Visual Rhetorics, in ed. Charles A. Hill and Marguerite Helmers (Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004), 54.

[19] Barack Obama, (Keynote Address at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, FleetCenter, Boston, MA, July 27, 2004).

[20] Barack Obama, The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream (New York: Vintage Books, 2008), 51.

[21] Gary Younge, “Is Obama Black Enough,” The Guardian, March 1, 2007, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2007/mar/01/usa.uselections2008, (accessed February 28, 2010).

[22] J. Anthony Blair, “The Rhetoric of Visual Arguments,” in Defining Visual Rhetorics, in ed. Charles A. Hill and Marguerite Helmers (Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004), 52.

[23] William Booth, “Street Artist Fairey Gives Obama a Line of Cred,” The Washington Post, May 18, 2008, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/artsandliving/style/features/2008/obama-poster-051808/graphic.html?sid=ST2008051602005, (accessed February 28, 2010).

[24] Laura Barton, “Hope – the image that is already an American classic,” The Guardian, November 10, 2008, http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2008/nov/10/barackobama-usa (accessed March 3, 2010).

[25] Brian Stelter, “Time Cover Sure Looks a Lot Like a Campaign Image,” The New York Times, December 22, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/22/business/worldbusiness/22iht-22time.18859117.html?_r=2, (accessed March 3, 2010).

[26] J. Cherie Strachan and Kathleen E. Kendall, “Political Candidates’ Convention Films: Finding the Perfect Image – An Overview of Political Image Making,” in Defining Visual Rhetorics, in ed. Charles A. Hill and Marguerite Helmers (Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004), 135-136.

[27] Gallup, “Gallup Daily: Obama Job Approval,” http://www.gallup.com/poll/113980/Gallup-Daily-Obama-Job-Approval.aspx, (accessed March 6, 2010).

[28] Frank Rich, “The Up-or-Down Vote on Obama’s Presidency,” The New York Times, March 6, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/07/opinion/07rich.html?em, (accessed March 7, 2010).

—

Written by: Jeremy Low

Written at: National University of Singapore

Written for: Dr. Luke O’Sullivan

Date: March 2010

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Obama and ‘Learning’ in Foreign Policy: Military Intervention in Libya and Syria

- Populism and Extractivism in Mexico and Brazil: Progress or Power Consolidation?

- Between Pepe and Beyoncé: The Role of Popular Culture in Political Research

- Agents of Change: Policy Entrepreneurs and Inducements in International Politics

- How Do Travel Vlogs Contribute to GDP’s Dominance in World Politics?

- The Cosmopolitan-Communitarian Clash over Syria in Conservative Politics