While Africa after de-colonialization has experienced many internal conflicts, there has been a puzzling lack of interstate wars. Why is this so? Given the historically rootless borders, lack of vital resources like water, and prevalence of dictatorships, one could have predicted that several African interstate wars would have taken place. I argue that national political structures in Africa combined with the existence of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and its principles of non-intervention and national sovereignty contributed to the relative lack of interstate wars from de-colonialization to the end of the Cold War. The explanatory framework is a simple rational choice framework, where national rulers are the central actors. These actors care mainly about their own continuation in office, and take into account how their present actions might affect the future. A modified version of Keohane’s (1984) theory on international regimes is presented formally. The model implies that non-intervention strategies can constitute an equilibrium even if there are short term gains from intervention.[2] The logic can be shortly summarized as follows: Political leaders refrain from intervening in another country because they fear this increases the probability of a foreign intervention into their own country later. This equilibrium becomes even more likely under the presence of a regime like the OAU.

In this paper, the state is shed as unit of analysis. The chosen unit of analysis is the national political leadership. This choice is based on insights produced by Africanist scholars on how national politics works on the continent. Political power, or more specifically staying in office, is portrayed as the ultimate objective for the actors, which resembles «realist» thinking on political motivation. However, as «neo-liberalist» scholars persuasively have argued, international regimes might matter for political outcomes, even if one models actors as instrumentally rational with fixed preferences. By combining these insights into a coherent theoretical framework, plausible explanations of the relative absence of interstate wars in Africa are generated.

Below, I first give a brief description of interstate wars in post-colonial Africa, and some alternative explanations of the puzzling «African Peace». Thereafter, I presents some central features of African politics that are of relevance to the later analysis, before I briefly describe the OAU. After that, I present this paper’s theoretical framework in a non-formal manner, whereafter I develop a simple game-theoretic model and present empirical implications. Finally, I look at how these different empirical implications match up against different pieces of empirical evidence.

Interstate wars in Africa

Africa has seen its fair share of conflicts after de-colonialization. From 1960 to 1999, 33 of the world’s 79 civil wars took place in Africa (Collier, Hoeffler and Sambanis, 2005:4-5). However, Collier and Hoeffler (2002) show that the high frequency of civil wars in Africa is largely due to the continent’s social and economic conditions, and not some Africa-specific effect. Nevertheless, there have been few African interstate wars or other direct governmental military interventions by African countries into other African countries.[3] As will be elaborated on below, Africa has seen fewer (intracontinental) interstate wars relatively (wars/countries) than regions such as the Middle East and Asia in the period from 1960 to the end of the Cold War.[4] Francis (2006:75) lists the interstate wars in Africa, and these were «Ethiopia-Somalia in 1977-78, Uganda-Tanzania in 1978-79, Ghana-Mali in the 1980s, Nigeria-Cameroon, Mali-Burkina Faso 1986, and recently between Eritrea and Ethiopia, 1998-2000».[5] In addition the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset (Gleditsch et al., 2002) counts the border conflict between Algeria and Morocco in 1963 and Chad’s conflicts with Nigeria and Libya in 1983 and 1987 respectively.[6] Moreover, there have been some «internationalized internal armed conflicts» where governments of African states have intervened on both sides, notably in the Congo Wars and in the conflict involving, among other actors, Angola and South Africa.

Nevertheless, the number of interstate wars between African countries in this period was quite low, particularly when considering the large number of states, and the many potential border disputes (see Englebert et al., 2002). According to Francis (2006:76) the few traditional interstate wars that have taken place have often been over contested borders. Even so, due to the nature of African borders, arbitrarily drawn up by colonial powers with little ethnic or geographical rationale, one could have expected more border-conflicts in Africa. Weak states without deep historical roots, dispersion of ethnic groups across borders, little economic integration in the form of bilateral trade and FDI, and dictatorial rule should all have contributed to a high probability of interstate war, but Africa saw relatively few.[7] Lemke (2003) has called this puzzling trait the «African peace».

Some explanations for the African Peace have been offered. For example, Lake and O’Mahony (2006) argue that a low average state size reduces the probability of interstate wars and this could help explain the low number of wars in Africa after 1960. This mechanism might be complementary to those presented in the analysis below. A second explanation relates to the broader geo-political context, and the roles of the USA and the Soviet Union more in particular. The superpowers established spheres of influences comprising various African states. One argument is that the potential costs of an interstate war between two or more African states, perhaps expanding to draw in the superpowers themselves, made the USA and Soviet Union use their influence to reduce the probability of African governments going to war in the first place (see e.g. Clapham, 1996: 17-18). This may contribute to explain the relative lack of interstate wars in Africa during the Cold War, but it is unlikely the whole story: One indication is that other regions, like Asia and the Middle East, were also arenas for superpower rivalry, and these regions experienced a higher relative frequency of interstate wars in the same period. Thirdly, Francis (2006:75) points out that interstate wars are often costly, and that limited resources on the part of African rulers and states might explain the absence of wars. This is also possibly a relevant explanation. Nevertheless, the cost of waging and winning a war depends to a large degree on the relative capabilities of the parties (see Hegre et al. 2009). If your potential victim is weak in terms of military capabilities, a large fleet of jet-planes and high-tech equipment might not be necessary to go to war and ultimately win it. There were plenty of wars in 18th century-Europe for example, and as shown below, other regions with relatively similar levels of economic development experienced a higher frequency of interstate wars. Hence, one should look for additional explanations of the African peace.

The political structure of post-colonial Africa

Africanist scholars have pointed out differences in political structures between Africa and the Western World, one being the structures of states. Labels such as «quasi-state» (Jackson, 1990) have been assigned to the «archetypical» African, state and Clapham (1998) advices us to think in terms of «degrees of statehood». I will not survey the literature on the African state, but rather provide a concentrated argument for why one should think twice before choosing the state as unit of analysis in an African context. Particularly within a rational choice framework, where actors are assumed to be unitary with complete and transitive preference-orderings, a misspecification of unit of analysis can cause problems for understanding political dynamics.

Weakly institutionalized state apparatuses and weak state capacity have been central in descriptions of African states. The African state’s abilities to penetrate society and conduct policies have been described as relatively weak when it comes to social and economic policy, but also when it comes to security-issues (Dokken, 2008). Although there has been important variation between countries (see Bach 2011), neo-patrimonial structures have dominated in African politics (e.g. Medard, 1996), with political processes and distributive policies being managed within vertical, personalized networks rather than through formal state institutions. This has led to the description of African political institutions as being «privatized» (Jackson, 1987 and Clapham, 1998). It is argued that formal state apparatuses in Africa are, or at least were, often nothing but formal, juridical shells, with state offices being personal «possessions rather than positions» (Jackson, 1987:528). Others have described African politics as «informalized» (Chabal and Daloz, 1999).

Another reason for being skeptical towards the state as a unit of analysis in Africa is the prevalence of dictatorship on the continent. Up until the dramatic political events in the early 1990’s, post-colonial Africa was mainly ruled by dictators (e.g. Bratton and van de Walle, 1997). A couple of small countries like Botswana and Mauritius have had relatively stable democracies since de-colonialization. However, most of the newly created states fell to dictatorial rule under Huntington’s (1991) second reverse wave after de-colonization. It is problematic to assume that ‘national interests’ are followed even in democracies, partly because the concept is difficult to define (Arrow, 1951; Schumpeter, 1976). Additionally, policy makers have their own particular interests that might deviate from those of their electorates. In dictatorships, the lack political accountability generating mechanisms like free and fair elections, the right to organize, and freedom of speech makes it even harder to assume that political leaders will follow the interests of citizens. Thus, when combining the lack of political accountability mechanisms with the personalized style of African politics, one has a situation where political leaders’ interests are crucial to political decision making.

This should have implications also for analysis of African international politics. Clapham (1996:62) argues that as a general rule, «it may be assumed that African leaders sought to maximize their own security and freedom». Clapham deals largely with revenue-generating foreign policies, but as I argue below, the interest in keeping office also has implications for the reluctance of African leaders to wage interstate wars. A better unit of analysis than the state is therefore the political leader, perhaps also including his crucial backers, the winning coalition (Bueno de Mesquita et al., 2003). Guerilla leaders and other actors not in government have sometimes been important in African international affairs (Clapham, 1996). However, the analysis here will focus on interaction between actors represented within the OAU-framework, and therefore only government-leaders will be recognized explicitly as central actors.[8]

Having argued that privatized politics and dictatorial government should lead meto utilize the ruler and his backers as the central unit of analysis, I need to make assumptions on their preferences. The main assumption made here is that they care largely about survival in office. Personal power is a strong motivational force in its own right, but other interests can also be served best through holding political office (see Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003). In post-colonial Africa, political office has been instrumental for controlling revenue streams from natural resources and trade, and political power has also been extensively used to appropriate economic resources from corruption and property grabbing. One extreme example is Mobutu’s amassment of a personal fortune that made him one of the three richest persons in the world (Sørensen, 1998:80). Even if rulers want to promote particular ideologies or support ethnic brethren, political office is the key instrument to achieve also such aims. I will therefore in the following assume that leaders are mainly motivated by holding office, but I allow for other objectives as well, as becomes clear from the specification of gains from intervening into another country below.

The OAU

With the new state system in Africa in the 1960s emerged the OAU. The OAU was established at a conference in Addis Abeba in 1963, with representatives from 30 African states present. The Pan-African movement, led by Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah had hoped to use an African-wide IGO as a vehicle for promoting African integration, but there were several blocs of countries represented at the conference with different aims for the scope and depth of such an organization (Francis, 2006:16-24). The blocs finally converged around the OAU Charter. The Charter included principles stating opposition towards colonialism on the continent and white minority rule in South Africa and Rhodesia.[9] However, the principles most relevant for the analysis here are the principles of «Non-interference in the affairs of States» and «Respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of each State and for its inalienable right to independent existence» (OAU Charter, 1963:4). According to Dokken (2008:19) «the OAU’s explicit focus on national sovereignty underscores how important the concept of state security was to the organization. OAU members were committed to respecting the territorial integrity and independence of all African countries».

National sovereignty has been a basic cornerstone in international politics more generally, but in African international relations the principle has been stressed to a comparatively high degree. One reason might be that any breach of the principle of sovereignty or territorial integrity could carry with it the risk of fall from power for political rulers in these newly created and perceived unstable states. Herbst (1989) has called it a paradox that Africa with its artificially created borders has seen so few border adjustments and revisions. Given the motivational force of continuation in office for African rulers, however, the stress put on these principles could be interpreted as a quite rational response. It was especially important for African governments to not break the principles of national sovereignty and territorial integrity, because «all parties know that once African borders begin to change there would be an infinite period of chaos», and the OAU was «instrumental in establishing the decision-making rules that created the boundaries and promoted their stability» (Herbst, 1989:689). Clapham (1998:145) also argues that the embracement of the Westphalian norms of state sovereignty and non-interference was instrumentally motivated: «[Q]uasi-statehood understandably led the rulers of weak states to place an emphasis on sovereignty … The key criteria for absolute sovereignty – the maintenance of existing frontiers, the insistence on the principle of non-intervention in the internal affairs of states, and the claim to the state’s right to regulate the management of its own domestic economy – were built into such documents as the Charter of the Organization of African Unity». The insights provided by Herbst and Clapham will be specified and formalized below.

Theory and context; a modified version of Keohane’s theory

A common statement in the Africanist literature is that much theorizing in political science is based on Western experiences. The implication sometimes drawn is that such theorizing is unfruitful when applied to the African context, and that Africanists should develop novel frameworks (e.g. Dunn and Shaw, 2001). This implication might be drawn too far. If one throws away existing theoretical frameworks for understanding politics, whether institutionalist or rational choice-based, one wastes a lot of valuable insight. Development economists, for example, have generated insights on how developing economies, such as those of African countries, work by using modified frameworks from general economic theory. The same strategy of modifying existing theory to suit the particular context can be used for understanding African politics. Here, Keohane’s (1984) theory of international regimes and cooperation will be modified by taking into account that political rulers rather than states are the central actors in African international politics.

It may be useful to consider the OAU as an international regime. Krasner (1982:186) defines international regimes as «sets of implicit or explicit principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures around which actors’ expectations converge in a given area of international relations». Keohane, in «After Hegemony», developed a theoretical framework for understanding how international regimes may contribute to enhancing cooperation between actors, particularly states. One of Keohane’s main points of departure is game theory, although he does not provide formal analysis. According to Keohane, several types of interactions between states in the international system have a «prisoner’s dilemma» structure. The key feature of this interaction structure is that the dominant strategy in one-shot games is to not cooperate. The equilibrium where all actors choose non-cooperation is, however, not optimal, and actors would have been better of by coordinating on cooperation.

However, when moving from one-shot to infinitely repeated games, the so-called folk-theorem (e.g. McCarty and Meirowitz, 2007:260-61) implies that there are an infinite number of subgame perfect Nash equlibria (SPNE) where actors can rationally arrive at cooperative outcomes. Rational actors can choose to cooperate because they will be punished in the next round of the repeated game if they do not cooperate. In other words, fear of punishment in the future may induce cooperation, even if there are short-term gains from not cooperating.

International relations are characterized by such «repeated games-structures» with actors that are likely to engage in interaction several times also in the future. Keohane’s main point is that international regimes exercise several functions that will increase the probability of arriving at cooperative equilibria. International regimes are designed to enable «stable mutual expectations about others’ pattern of behavior and to develop working relationships that will allow the parties to adapt their practices to new situations» (Keohane, 1984:89). International regimes bring a stabilizing element into international politics because they introduce, solidify or specify practices, principles and norms. This makes cooperation between rational, self-interested actors easier to establish because actors can converge around the norms and principles set down by the regime.

Keohane specifies the cooperation-enhancing functions of international regimes: Regimes can, for example, reduce information costs, making information on others’ actions easier to obtain and more reliable. Breaches of cooperation can therefore more easily be quickly identified, and with a higher degree of certainty. Regimes also provide forums for institutionalized dialogue between actors. This reduces the transaction costs related to engaging in dialogue and generally reduces uncertainty, thereby also mitigating the probability of unfounded breaches in cooperation based on fears that others might be in the process of breaching it. The probably most important function, however, is that the principles, norms and procedures laid down by the regime function as measuring rods for behavior. By clearly specifying what constitutes prescribed cooperative behavior, it is easier to establish when certain actors have breached cooperation. This again will lead to more certain punishment, which again deters actors from breaching cooperation in the first place.

A game-theoretic model

As indicated above, the model constructed here takes the national political rulers as units of analyses. The rulers carry a flag and represent a state, but it is really the preferences and goals of rulers that matter. Personal enrichment and power are identified as central goals in the non-formal literature on African politics, and this should carry over to a formal model’s actors and their utility functions. Personal wealth and power in African politics hinges upon control of the formal state apparatus. I can therefore parsimoniously model these regimes as interested in maximizing their probability of remaining in office. When I combine these insights with Keohane’s (1984), I can establish a model that helps explain the lack of interstate wars in Africa under the OAU.

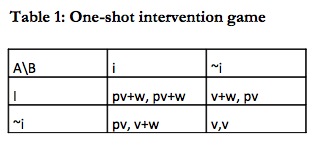

First I analyze the hypothetical one-shot prisoner’s dilemma game, where African rulers play against each other once. There are two actors (or players), ruler A and ruler B. The actors are identical in terms of parameters, pay-offs and possible strategies. The actors can either intervene, i, or refrain from intervening, ~i, into the other’s country. The rulers obtain a utility of v, from staying in power in their own state. If A intervenes or conducts an act of aggression against B, he gains a price, w, for example in the form of occupied territory, resources or utility gained from helping ethnic brethren abroad. When there is absence of external intervention in a country, the ruler in the country remains in office with a probability of 1. When there is an intervention, the ruler remains in office with a probability p. I further assume that the expected utility loss stemming from experiencing foreign intervention is larger than the utility gain from intervening, that is: (1-p)v>w. This follows the assumption that rulers are mainly concerned about office; even a relatively small probability of losing office cannot be compensated from the gains of intervening abroad. Table 1 illustrates the one-shot game:

Playing i is a dominant strategy for both players, since pv+w>pv and v+w>v. Both actors will gain from intervening, independently of what the other chooses. {i,i} is therefore the (only) Nash-equilibrium of the game. However, since (1-p)v>w, both players are worse off in this equilibrium than if they had coordinated on non-intervention. However, {~i,~i} is not a plausible solution to the one-shot game, since both players have individual incentives to deviate from this situation.

Playing i is a dominant strategy for both players, since pv+w>pv and v+w>v. Both actors will gain from intervening, independently of what the other chooses. {i,i} is therefore the (only) Nash-equilibrium of the game. However, since (1-p)v>w, both players are worse off in this equilibrium than if they had coordinated on non-intervention. However, {~i,~i} is not a plausible solution to the one-shot game, since both players have individual incentives to deviate from this situation.

What happens in a repeated games-structure? Could office-motivated African rulers escape the bad equilibrium of mutual intervention? Given certain assumptions, they could! The folk theorem states that there are infinitely many strategy-combinations that allow players to reach a better outcome, if the sequence of games is infinite (interpreted as unknown end-point of the game) and players are patient enough. Let me consider the simplest of these strategy-combinations, namely that all players play a grim-trigger strategy:[10] players start out cooperating in the first period, and play a history-contingent strategy in the following periods: If the other player cooperated in all earlier periods, then cooperate in this period. If the other player did not cooperate in at least one of the earlier periods, then don’t cooperate in this period. Cooperation in this game is ~i. The cooperative strategy can be simplistically stated as: «If you mind your own business and don’t intervene in my country, I won’t intervene in your country next time I have the opportunity». This may yield non-intervention SPNEs if the players are sufficiently patient, if the gains from intervening abroad relative to the gains of continuing in office are low or if the probability of losing office when experiencing foreign intervention is high.

I assume that all players have a discount factor of β, which is between 0 and 1. A low discount factor implies that the actor values the present relatively much compared to the future. I use a von Neumann-Morgenstern utility function, and the discounted utility for an actor from cooperating in every period, assuming that all players play grim-trigger, is:

I) v + βv+ β2v +….+ βnv+… = v/(1-β)

What is the discounted utility of playing i in the first period, thereby breaching the implicit or explicit cooperative agreement? Clearly, the player would be better of in the present period, as he gains an extra utility of w. However, the player will lose out in all subsequent periods, as pv+w<v. Moreover, I assume the ruler cannot come back to power once office is lost, and that he cannot gain from intervention from the period after office is lost. For simplicity, I also assume that all probabilities are independent. The discounted pay-off from breaching cooperation is thus:

II) (v+w) + β(pv+w) + β2(p2v+pw)….+ βn(pnv+pn-1w)…= (v+w/p)/(1-βp)

Hence, the rational African ruler chooses not to intervene if:

III) v/(1-β)>(v+w/p)/(1-βp)

One can see from inequality III) above that a high w, a low βand a low p contribute to the likelihood of intervention. In words, large gains from intervention, impatience and a low probability of being ousted from office given intervention by another player are factors that make breakdown of the non-intervention equilibrium more likely. I rewrite III) to:

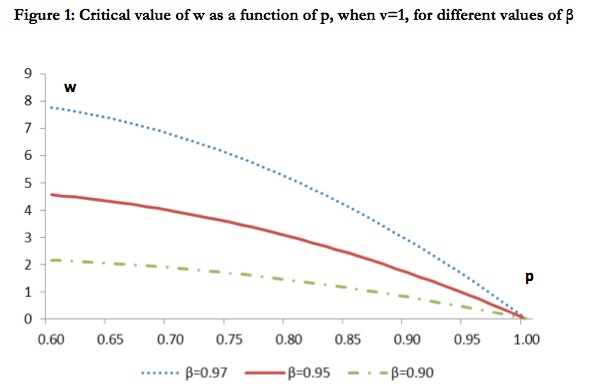

IV) p((v(1-βp)/(1-β))-pv>w

If one normalizes v to 1, and set the the value of p to 0.8 and β to 0.95, non-intervention is ensured whenever the value of w is lower than 3.04. That is, the value stemming from intervention has to be more than three times higher than remaining in office. If one recalibrates p to 0.95, the critical value of w is 0.90, which is still very high and indicates that the gain from intervention should be almost as high as the gain from sitting in office. For p equal to 0.99, the critical value of w falls to 0.19. One therefore needs a very low probability of being ousted from power after intervening in another country in this model to make intervention a likely strategy. Figure 1 shows how the critical value of w for breaching cooperation varies with p and β.[11]

What if B poses a direct threat to A? That is, what if the existence of B reduces the probability for A of staying in office, even if there is no intervention. Intervention in the foreign country with the intention of overthrowing the ruler next door might now actually increase the probability of staying in office. At least, the net reduction in probability of survival due to intervention is lower than in the model above. I model this by including a probability, q, of survival in the case of non-intervention. The ruler will now cooperate if the inequality in V) is satisfied.

V) v/(1-βq)>(v+w/p)/(1-βp)

Whether q is larger than or smaller than p, is context-contingent. However, it is straightforward to see from the comparison of III) and V), that the critical value of w will be lower, ceteris paribus, than in the analysis above. Rulers will therefore be more likely to intervene. If q is lower than or equal to p, the ruler will always intervene, given that w is not a too large negative number. One empirical prediction from the model is thus that external intervention in Africa was more likely to occur where the ruler of a country posed a direct threat to the ruler of another country. Were there certain types of intervention that could reduce q, but at the same time keep p relatively low? That is, was it possible to get rid of the dangerous foreign ruler, without generating too high risks of intervention from other actors in the future? Might proxy-wars, which Africa has seen many of, represent such a situation?

The idea of reciprocal mechanisms underlying non-intervention in African politics is not novel. Herbst (1989) provides an excellent qualitative presentation of the logic, mainly related to border-issues, and recognizes the relevance of international regime theory. Herbst (1989:689) explicitly claims that the reciprocal agreement followed by African leaders was that «one nation will not attack or be attacked by another as long as minimal administrative presence is demonstrated». The consequence of a conflict over borders could have produced a feared domino-effect throughout the continent, since most countries have had problems with secessionist groups or arbitrary borders including relatively larger powers like Nigeria and Zaire, whose leaders could otherwise have had the strongest incentive to attack neighbors. Herbst also touches upon the large number of African states. A large number of actors could increase the probability of a breakdown in a cooperative agreement, especially if there is actor heterogeneity and the actors play a strategy such as grim-trigger. This problem was not explicitly dealt with above. However, Herbst claims that the large number of actors was not crucial in Africa. Actually, the large number of bordering states implied that the consequences of a breakdown of a system would be even more immense, which could be interpreted as a low p in the model. Moreover, Africa had the OAU, with its likely stabilizing role on the system.

Plausibly, the interaction between the OAU-based international security regime and the specific domestic political context in many African states contributed to making the low-conflict equilibrium more likely. As mentioned, the low level of institutionalization, and correspondingly high level of personalization, of African politics meant that rulers often had a very large personal stake in remaining in power (high v). Moreover, conflicts could have potentially dramatic consequences in terms of cascades of revisions of «arbitrary borders» and changes in governments (low p). Hence, the political structure of the African «Quasi-State» (Jackson and Rosberg, 1982), and the nature of its borders and lack of historical legitimacy, may have played a vital role in deterring African governements from going to war with each other. The OAU likely enabled the regimes to coordinate more easily to avoid such potentially costly wars. Moreover, coordination was likely helped by the long tenures, and thus long time horizons (high β), of African leaders.

More specific political-economic aspects may also have contributed to the reduction in conflict risk. As mentioned, political office in post-colonial Africa was often used to generate substantial incomes for the ruler and his close supporters, which provided a strong incentive to hold on to power. One specific and important area was the control of revenues from trade across borders, both legal and illicit (see e.g. Bach, 1999). Hence, several actors, including those in power, often had strong incentives to stabilize existing border arrangements to ensure the continuation of particular trading patterns and practices in which they had made complementary investments. This could, in turn, contribute to reduced gains (lower w) and increased costs (lower v) resulting from border wars.

How might an international regime like the OAU matter in the model-framework above? Keohane (1984) specified the different functions an international regime might have for different states interacting, and these are also relevant when rulers are the unit of analysis. The main result from Keohane is that the existence of international regimes eases cooperative behavior. The explicit principles of non-interference and sovereignty set out in the OAU provided clear benchmarks for behavioral norms and made it easier for rulers to accurately point out when other rulers breached the cooperation on non-intervention. When it comes to providing yardsticks, the OAU also established the principle that he who controlled the capital was the legitimate leader of the state, thereby clearly defining who were and were not participants in the international regime. This rule provided «adequate information to allow other powers to understand where they can and, more important, cannot intervene in modern African politics» (Herbst, 1989:688). Additionally, the OAU provided a forum for diplomacy and talks, which again eased the flow of communication between rulers. This mitigated uncertainty and unfounded fears of another leader considering intervention. Information and transaction costs for political leaders were therefore likely lower under the OAU than if no such organization had existed. The OAU could also link localized events between two African countries to a broader framework. By multi-lateralizing African foreign policies, the OAU could potentially lead to several leaders reacting to breaches of a single country’s sovereignty, thereby impending larger costs on the intervener.[12]

How could one model the possible effects of OAU within the framework presented above? Indeed, several of the parameters in III) could be impacted. First, the likely more rapid response to an intervention by foreign leaders under a regime like the OAU will lead to «shorter time periods» in the model. This could be modeled through an increased discount factor, β. Second, w might decrease if other leaders than the one who faced intervention were more likely to push through different types of formal or informal sanctions on the intervening leader. Moreover, p might increase under the OAU: If intervention leads to an increased probability of one or several forms of retribution by either the leader intervened upon or other leaders, the future probability of losing office will be higher. A high β, a low w and a low p all make it easier for inequality III) to hold. The main empirical implication from the theoretical framework presented here is therefore that the OAU contributed to reducing the probability of foreign intervention in Africa, potentially through multiple mechanisms. According to former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere, the OAU developed into «a «trade union» of African leaders, essentially designing rules for their own survival» (Herbst, 1989:676). OAU has also been labeled «a club for dictators» (Meredith, 2006:680). The model above helps clarify how this club assisted the dictators in securing their vital interests of staying in power.

Empirical implications and pieces of evidence

It is admittedly difficult to draw precise conclusions on the empirical relevance of the model presented, including on the actual relevance of the OAU. We cannot rerun history and observe the counterfactual, namely post-colonial Africa without the OAU. As Herbst (1989:690) notes «[t]he OAU itself serves as the nominal «strongman» to remind leaders of the continent’s norms and prevent any defections, but given the self-evident dangers, it is unclear if the OAU is even needed to preserve the current boundary system». Nevertheless, I will tease out different observational implications from the model and evaluate their empirical relevance with available evidence.

I will not conduct a statistical analysis here, simply because such analysis has been conducted in a proper manner before. Drawing on the Correlates of War data and using a global sample from 1950-1992, Lemke found that African countries were significantly less likely to engage in interstate wars, even when controlling for several other variables. The «African Peace» is therefore not only a trait to be found in descriptive statistics:

Of specific interest is the African Dyad variable. It suggests there is something different, something exceptional about Africa in terms of interstate war. The negative coefficient for this variable indicates that African dyads are disproportionately less likely to experience war than are non-African dyads. Not only is the effect statistically significant, but it is also substantively large. The risk ratio indicates that African dyads are only about one-tenth as likely to experience war as are other dyads. Even controlling for all of the «usual suspects», African dyads are disproportionately peaceful according to this analysis (Lemke, 2003:119).

Lemke shows that parts of this effect can be explained by missing data and measurement error. Nevertheless, even after adjusting for these methodological factors, there is still a significant Africa-effect. This suggests that there was something substantively specific about African international politics from de-colonialization to the end of the Cold War. My model suggests that the structure of African politics, that is the interaction of national political structures related to personalized politics and the existence of the OAU, might be a vital part of the explanation for why Africa was different.[13]

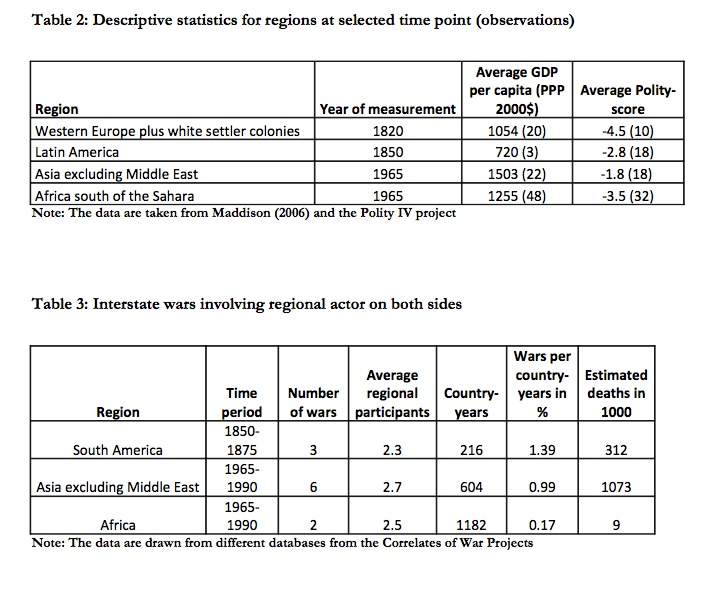

One indication of the OAU’s relevance is based on the comparison of the post-colonial African experience with historical epochs in other regions. Three relatively comparable cases can be picked out: Asia after de-colonialization in the second half of the 20th century, Latin America after de-colonialization in the 19th century, and Europe in the 17th and 18th century when its border and state structures were still far from frozen. How settled state and border structures are is one important variable, but so are the level of economic development and the nature of national political regimes in the region. As Table 2 shows, there are relatively small differences between the four cases in terms of average degree of democracy and GDP per capita-level. The Asian experience also coincides temporally with the African. The Western European numbers most likely show a higher income level and degree of democracy than the real numbers in the 17th and 18th centuries, as the lack of data forces me to use 1820 numbers.[14]

As Table 3 shows, Asia had a higher incidence of war than Africa from 1965 to 1990; the number of wars divided by country-years in the period was almost six times higher in Asia, excluding the Middle East. When it comes to Latin America between 1850 and 1875, the frequency of interstate wars was even higher than that in Asia from 1965-1990. It is difficult to find comparable data for 17th and 18th-century Europe, but a cursory reading of European history indicates that there was a much higher incidence rate here than that found in Africa under the OAU, and possibly also than in the other cases.[15] The incidence rate of war in 19th-century Europe is shown by Lake and Mahony to have been well above that of post-colonial Africa, especially after the breakdown of one of the first international regimes on security, the Vienna Congress System. The system was established after the Napoleonic Wars, but broke down after a few years.[16] The logic of the model is actually supported by the relatively low incidence of wars under the Vienna Congress system, as it can be considered a relatively structured European security regime. Such a regime lacked in Latin America during the period under investigation, as Simón Bolivar failed in his attempts to create a union between the newly independent countries. In Asia, ASEAN was created in 1967, but crucially only included five Southeast Asian countries until 1984.[17] Therefore, the existence of the OAU in post-colonial Africa separates Africa from the other cases. The other factors, namely lack of historically solidified boundaries, low level of economic development and a high incidence of non-democratic regimes, were relatively similar between the cases. These variable-configurations lend support to the claim that the OAU contributed to a relatively low incidence of interstate wars in Africa.

Another type of (indirect) evidence is the actions taken by the OAU and its members when actual conflict or dispute over territory broke out. The norm of territorial integrity was tested eight times after 1973 (Zacher, 2001). Only one of these violations of the territorial norm was successful; the Moroccan inclusion of Western Sahara even before de-colonialization from Spain in the mid-1970s. Most of the OAU-members opposed the move, but were unsuccessful in pressuring the Moroccans. In all the other territorial disputes, the norm of territorial integrity triumphed, and the aggressors came out empty-handed. Also before 1973 the OAU is credited for successfully defending the norm of territorial integrity. In 1964, when Somalia sent troops into Ethiopia and Kenya, «Somalia was pressured by the OAU to withdraw» (Zacher, 2001:230). Likewise in 1965, «the OAU also successfully pressured Ghana to withdraw from a small area of neighboring Upper Volta» (Zacher, 2001:230). One important implication of these unsuccessful attempts is their effect on the beliefs of African leaders when it comes to the probability of gaining territory by invasion without incurring costs imposed by other members. Since the OAU-norms were consequently followed, it would not be likely that future ventures could lead to easy gains through intervention. In terms of the model, the estimated w was low, and probably also negative if large and coordinated sanctions from OAU-members followed attempts of occupation. According to Zacher, «[t]he OAU members have exerted significant diplomatic pressure on aggressing states, and they have influenced outside powers to back OAU positions against territorial aggression» (Zacher, 2001:231). This, in turn, would lead rational leaders to think twice before intervening into a neighboring country for territorial gain.

An additional argument for the plausibility of an effect of the OAU-based security regime is derived from cases where one a priori could have expected that different African actors would have intervened («most likely cases»), but where intervention did not happen. Clapham (1996:188-90) assesses three such cases, where actors could have intervened on humanitarian grounds or because of other concerns: Amin’s regime in Uganda, Bokassa’s regime in The Central African Republic and Nguemas’ regime in Equatorial Guinea.[18] As Clapham notes, these cases show the malfunctioning of the principles of sovereignty and non-interference when it comes to protecting citizens and humanitarian rights. But, they also illustrate how these principles could function in the interest of African rulers wanting to stay in power. Despite criticism from many corners, other African countries and the OAU as an organization did little to act upon human rights abuses in these three countries and the passivity can be explained by the framework above.

All three regimes came to an end in 1979, and as the Tanzanian intervention into Uganda shows, there are no deterministic regularities in the social sciences.[19] Indeed Clapham (1996:189) argues that when the three regimes, including that of Amin’s, were overthrown, «the sense of continental relief was such that external involvement was tacitly ignored». If this is true, and it was known by Nyerere before the invasion, the model would suggest that the estimated high p could have been crucial to Nyerere before taking the invasion-decision. Tacit approval by other leaders meant a minimal risk of retribution at a later point in time. There is more to this case that actually illustrates the logic of the model. Amin had before the invasion allowed his soldiers to plunder in Northern Tanzania, and Nyerere’s response can therefore be considered as an illustration of the reciprocal logic of the model: Amin’s disrespect for the territorial integrity of a neighbor triggered a response that «in the next period» cost him his power. Moreover, Meredith (2006:238) claims that it was the fear of dissension within Amin’s army, his most important backers, that led him to allow troops to go into Tanzania in an attempt to divert them from internal fighting. In terms of the model’s logic, Amin feared that his chance of losing power would be high without intervention, but the intervention triggered a response from a foreign ruler that led to his downfall.

One of the hypotheses derived above was that intervention was more likely if the potential intervened-upon country posited a government that was considered threatening to the security of the leader in the potentially intervening country. Regional expansions of civil wars in Africa have come in circumstances where national regimes outside the civil war zone have had large stakes there. Although these are not traditional interstate wars, the interaction pattern sheds some light on the logic proposed above. The ECOWAS-force, ECOMOG, which intervened in the Liberian civil war in the early 1990s, was largely initiated by Nigeria. It can be argued that the spill-over potential of this civil war was one factor that led Nigerian and other West-African leaders to intervene in that conflict (Dokken, 2008:64). A spill-over of conflict is, of course, not desired by leaders who would like to stay in power. Dokken explicitly claims that the Babangida-regime in Nigeria felt threatened and believed that its own government could be overthrown as a consequence of Charles Taylor’s successes in Liberia. Another interesting point is that the Nigerian President Babangida actually justified the invasion with a reference to defense of territorial integrity, as Charles Taylor’s forces had «killed thousands of Nigerians who were hiding in the Nigerian Embassy» (Dokken, 2008:64). By invoking the norm of territorial integrity after the embassy attack, the Nigerian government could thereby more easily escape reciprocal actions from other actors. Note also that the intervention here was under the ECOWAS-umbrella. A cooperative intervention reduces the risk of making enemies with other rulers within the «regional security complex» (Buzan, 1991), thereby making it possible to uphold a cooperative equilibrium after the end of the Liberian conflict.

A second example comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo’s (DRC) bloody civil wars, where several foreign actors intervened. The total collapse of the Congolese state posited a grave security threat to many neighboring regimes, such as those in Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda. The Kagame-regime in Rwanda, for example, was threatened by the Hutu-militias hiding in the Congolese jungles. This security threat was arguably the most important reason for the Kagame-regime intervening, although some analysts point to many different objectives underlying the intervention, especially in the Second Congo War (Longman, 2002). One objective was likely the importance of using the external enemies in the DRC as a means of shoring up support inside Rwanda and uniting the country behind the regime (Longman, 2002). This is in line with the argument of regime security being a dominant motivation. Several actors intervened in the Second Congo War, and not all of these faced imminent regime threats from events in the DRC. However, the pattern of several regimes intervening on behalf of the Congolese government, like the regimes of Zimbabwe, Angola, Namibia, Chad, Sudan and Libya seems to fit the logic of reciprocal intervention, even if these actors did not attack for example Rwandan territory, but operated within Congo itself. The principles of sovereignty and upholding a legal national government in the DRC were the official justifications behind for example Zimbabwe’s intervention (Rupiya, 2002), although the motivation of controling economic resources is likely to have been a key driving force (Koyame and Clark, 2002). Nevertheless, security of regime-considerations was among the most important factors for the first actors intervening, and the war does therefore not dramatically undermine the model. One also has to remember that this is not a case within the core domain of the model, as it is not a traditional interstate war and the war played out in the waning days of the OAU, with the relative decline of the principle of non-interference (Dokken, 2008; Francis, 2006).

One of the best tests of the hypotheses deduced above might however come from observing the pattern of interstate conflicts in Africa over the next decades. The international political environment has changed in Africa after the end of the Cold War, temporarily culminating with the construction of the African Union to replace the OAU in 2001. Under the AU-regime «the notion of national sovereignty does not have such a strong standing as used to be the case with the OAU» (Dokken, 2008:21). In the words of Francis (2006:129) «[p]olitical sovereignty is no longer sacrosant, and it is now replaced by the right to intervene in member states in situations of state collapse, war crimes, genocide and for human right protection purposes». If one asserts that international regimes and their make-up might matter for conflict-patterns, the empirical prediction is that there will be more interstate conflicts in Africa in the years to come.[20] Indeed, the perhaps most clear-cut example of a traditional interstate war, between Eritrea and Ethiopia, came in the last days of the OAU, after the principles of that international regime had been weakened.[21]

Summary and conclusions

It may seem strange that a framework developed by Keohane (1984) for understanding the cooperation between states in political economic matters can be modified and applied to security issues on the African continent. However, as Jackson (1987:521) notes, international regimes are relevant also when it comes to issues of sovereign statehood and intervention. The Keohanian framework was modified so that states were substituted with political leaders as units of analysis. A formal model was specified to provide precision and stringency to the argument. In this model, the actors’ cooperation relate to not attacking each other’s territories, driven by the fear of future retribution.

The OAU has been called a failure by many analysts for not providing security to citizens of different African states from internal civil war, human rights violations and persecution. This might be true, but given the identification of the rulers as relevant actors’ and their motivational structure the OAU was certainly not a failure for the rulers themselves. The OAU contributed to relative international stability, thereby bolstering the position of Africa’s Big Men, known for their long tenures in power (Chabal and Daloz, 1999:32-37). Some empirical evidence was also presented, and these pieces of evidence were largely in line with the model’s predictions. As Jackson and Rosberg (1982:18) acknowledged, «there is a common interest in the support of international rules and institutions and state jurisdictions in the African region that derives from the common vulnerability of states and the insecurity of statesmen», and this insight is core to the analysis above.

One contribution from this article is an elaboration on the link between national regime type and interstate war. The argument in this article does of course not rock the boat for the democratic-peace thesis. The empirical regularity that democracies seldom fight each other is one of the strongest regularities in the social sciences.[22] However, the argument in this article could provide insights into the specific conditions that may lead dictators to refrain from engaging in warfare. African dictators were often in power for a long time, and interacted under a clearly specified framework set out by the OAU. Combined with a top priority of continuation in office, these features may have led the dictators to coordinate on a non-intervention equilibrium, out of fear for retribution and loss of office in the future. Would dictators with a high probability of staying in office despite intervention, with a short time horizon, or interacting under a less well-specified international regime have acted similarly? I believe not. My proposition is that African dictators did not refrain from international warfare because of an inherent respect for others’ borders. They by and large minded their own business because they were afraid that acting otherwise could cost them their position in the future.

Carl Henrik Knutsen is Ph.D Fellow at the Department of Political Science, University of Oslo and Associated Researcher at CSCW, PRIO and at ESOP, Department of Economics, University of Oslo. This piece was originally published in Dynamiques Internationales.

Literature

ARROW, Kenneth, Social Choice and Individual Values, New York: Wiley.

BACH, Daniel, « The African neopatrimonial state as a global prototype » , in CLAES, Dag Harald, and KNUTSEN, Carl Henrik (eds.), Governing the Global Economy: Politics, Institutions and Economic Development, London: Routledge, 2011, pp. 153-159.

BADURA, Jason, and HEO, Uk, « Determinants of Militarized Interstate Disputes: An Integrated Theory and Empirical Test », paper presented at The Annual Meeting of the International Studies Association, San Diego, March 21st-25th 2006.

BRATTON, Michael, and VAN DE WALLE, Nicolas, Democratic Experiments in Africa. Regime Transitions in Comparative Perspective, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

BUENO DE MESQUITA, Bruce, SMITH, Alistair, SIVERSON, Randolph M., and MORROW, James D., The Logic of Political Survival, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003.

BUZAN, Barry, People, States and Fear: An Agenda for International Security Studies in the Post-Cold War Era, London: Harvester WheatsHeaf, 1991.

CHABAL, Patrick, and DALOZ, Jean-Pascal, Africa Works: Disorder as Political Instrument, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999.

CLAPHAM, Christopher, Africa and the International System. The Politics of State Survival, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

CLAPHAM, Christopher, « Degrees of statehood », Review of International Studies, vol. 24, n0 2, 1998, pp. 143-57.

COLLIER, Paul, and HOEFFLER, Anke, « On the Incidence of Civil War in Africa », Journal of Conflict Resolution, vol. 46, n0 1, 2002, pp. 13-28.

COLLIER, Paul, HOEFFLER, Anke, and SAMBANIS, Nicholas, « The Collier-Hoeffler Model of Civil War Onset and the Case Study Project Research Design », in COLLIER, Paul, and SAMBANIS, Nicholas (eds.), Understanding Civil War. Volume 1: Africa, Washington D.C.: The World Bank, 2005, pp. 1-33.

CORRELATES OF WAR PROJECT, « State System Membership List, v2008.1. », 2008 (http://correlatesofwar.org).

DOKKEN, Karin, African Security Politics Redefined, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

DUNN, Kevin, and SHAW, Timothy M. (eds.), Africa’s Challenge to International Relations Theory, Houndmills: Palgrave, 2001.

ENGLEBERT, Pierre, TARANGO, Stacy, and CARTER, Matthew, « Dismemberment and Suffocation: A Contribution to the Debate on African Boundaries », Comparative Political Studies, vol. 35, no 10, 2002, pp.1093-1118.

FRANCIS, David J., Uniting Africa – Building Regional Peace and Security Systems, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006.

GHOSN, Faten, PALMER, Glenn, and BREMER, Stuart, « The MID3 Data Set, 1993–2001: Procedures, Coding Rules, and Description. » Conflict Management and Peace Science, vol. 21, n0 2, 2004, pp. 133-54.

GLEDITSCH, Nils Petter, WALLENSTEEN, Peter, ERIKSSON, Mikael, SOLLENBERG, Margareta, and STRAND, Håvard, « Armed Conflict 1946-2001: A New Dataset », Journal of Peace Research, vol. 39, no 5, pp. 615-637.

GOLDSMITH, Benjamin E., « A Liberal Peace in Asia? », Journal of Peace Research, vol. 44, n0 1, 2007, pp. 5-27.

HEGRE, Håvard, HØYLAND, Bjørn, and KNUTSEN, Carl Henrik, « Development and the Utility of Interstate War », Oslo: University of Oslo and Prio, Working Paper, 2009.

HERBST, Jeffrey, « The Creation and Maintenance of National Boundaries in Africa », International Organisation, vol. 43, n0 4, 1989, pp. 673-92.

HUNTINGTON, Samuel P, The Third Wave. Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century, Oklahoma: The University of Oklahoma Press, 1991.

JACKSON, Robert H., « Quasi-States, Dual Regimes and Neoclassical Theory: International Jurisprudence and the Third World », International Organization, vol. 41, n0 4, 1987, pp. 519-50.

JACKSON, Robert H., Quasi-States: Sovereignty, International Relations and the Third World, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

JACKSON, Robert H., and ROSBERG, Carl G., « Why Africa’s Weak States Persist: The Empirical and the Juridical in Statehood », World Politics, vol. 35, n0 1, 1982, pp. 1-24.

KEOHANE, Robert O., After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

KOYAME, Mungbalemwe, and CLARK, John F., « The Economic Impact of the Congo War », in CLARK, John F. (ed.), The African Stakes of the Congo War, Houndmills: Palgrave, 2002, pp. 201-23.

LAKE, David A., and O’MAHONY, Angela, « Territory and War: State Size and Patterns of Interstate Conflict », in KAHLER, Miles and WALTER, Barbara F. (eds.), Territoriality and Conflict in an Era of Globalization, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 133-55.

LEMKE, Douglas, « African Lessons for International Relations Research », World Politics, vol. 56, no 1, 2003, pp. 114-38.

LONGMAN, Timothy, « The Complex Reasons for Rwanda’s Engagement in Congo », in CLARK, John F. (ed.), The African Stakes of the Congo War, Houndmills: Palgrave, 2002, pp. 129-44.

MADDISON, Angus, The World Economy, Paris: OECD Publishing, 2006.

MCCARTY, Nolan, and MEIROWITZ, Adam, Political Game Theory: An Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

MÉDARD, Jean-Francois, « Patrimonialism, Neo-Patrimonialism and the Study of the Post-colonial State in Subsaharian Africa », in MARKUSEN, Henrik Secher (ed.), Improved Natural Resource Management – the Role of Formal Organizations and Informal Networks and Institutions, Occasional Paper 17, International Development Studies, Roskilde University, 1996, pp. 76-97.

MEREDITH, Martin,The State of Africa – A History of Fifty Years of Independence, London: The Free Press, 2006.

OAU, « The OAU Charter, 25 may 1963 », 1963 (www.africa-union.org)

PALMER, R.R., COLTON, Joel, and KRAMER, Lloyd, A History of the Modern World, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002.

PUTNAM, Robert D., « Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: the Logic of Two-Level Games ». International Organization, vol 42, no 3, 1988, pp. 427-60.

RAKNERUD, Arvid, and HEGRE, Håvard, « The Hazard of War: Reassessing the Evidence for the Democratic Peace ». Journal of Peace Research, vol 34, no 4, 1987, pp. 385-404.

RUPIYA, Martin R., « A Political and Military Review of Zimbabwe’s Involvement in the Second Congo War », in CLARK, John F. (ed.), The African Stakes of the Congo War, Houndmills: Palgrave, 2002, pp. 93-105.

SAIDEMAN, Stephen M., The Ties That Divide – Ethnic Politics, Foreign Policy & International Conflict, New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

SARKEES, Meredith Reid, « The Correlates of War Data on War: An Update to 1997 », Conflict Management and Peace Science, vol 18, n0 1, 2000, pp. 123-44.

SCHUMPETER, Joseph A., Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, New York: Harper Perennial, 1976.

SØRENSEN, Georg, Democracy and Democratization. Processes and Prospects in a Changing World, Boulder: Westview Press, 1998.

ZACHER, Mark W, « The Territorial Integrity Norm: International Boundaries and the Use of Force », International Organization, vol. 55, no 2, 2001, pp. 215-50.

[1] I would like to thank Scott Gates, Jon Hovi, an anonymous reviewer, and the participants at the 3rd Annual GARNET Conference in Bordeaux and at the CSCW workshop on The Dynamics of Institutional Change and Conflict in Oslo for very helpful comments and suggestions.

[2] The term ’intervention’ is broader than that of starting an interstate war. The main type of intervention I am concerned with here, however, is interstate war. Hence, the terms are used interchangeably throughout the text.

[3] One important modification is that Africa has experienced several shadow or proxy wars. These have often taken the form of a government in country A supporting a rebel movement in country B, which it is sympathetic towards. Typically, the government in country B also supports an armed opposition movement in country A. Saideman (2001) claims that intervention, when interpreted more broadly, has been far more common in Africa than usually acknowledged. One should therefore not overdo the point of lacking external interventions in Africa. However, the choices of more subtle types of intervention in Africa are interesting, and these choices can be related to the logic of the analysis below. Intervention through proxy-war might be a less risky project for a leader than a full-blown interstate war. It might for example be harder establish precisely the degree of external intervention, which might lessen the risk of sanctions from other parties.

[4] It should be noted that the explanatory framework presented below is related to the existence of the OAU, and the principles of non-interference and national sovereignty play important roles. These norms have in recent years been increasingly challenged by different sets of norms related to human rights protection abroad and the «Responsibility to Protect», globally and in Africa. In Africa, this change was accompanied by the formation of the African Union, and the demise of the OAU. Indeed, the model framework presented below indicates that these trends may be followed by another trend in the coming decades; that of increased relative frequency of interstate wars in Africa. This will be discussed briefly in the conclusion.

[5] Figures from the Correlates of War dataset, based on a more stringent definition, exclude several of these instances when coding interstate wars (Ghosn, Palmer and Bremer, 2004).

[6] For references to other minor disputes, see e.g. Englebert et al. (2002).

[7] The literature on determinants of interstate conflicts is large. See e.g. Badura and Heo (2006) for a review and some empirical results.

[8] The game modeled below focuses on the interaction of rulers, but it could certainly be modified as a kind of two-level game (Putnam, 1988), by incorporating that rulers are linked to a winning coalition of backers through patron-client networks. The main logic of the model below is that rulers motivated by staying in power will not invade other countries because of the risk of retribution from other actors, and the subsequent increased risk of losing office. In a two-level game, the winning coalition could be modeled as motivated by material consumption, and backs its ruler if he maximizes its abilities for consumption. What implications would this have? If there are material resources to be gained from invading a foreign country, the winning coalition might force the ruler to undertake more adventures abroad than implied by the model presented below. However, if the main concern of the winning coalition is keeping their ruler in office at any cost to maintain material advantages related to patronage, the winning coalition would not want to increase the probability of the ruler losing office. If so, there is not much to be gained from a two-level model, as it yields similar predictions as the more parsimonious model.

[9] Since the eradication of white minority rule was an explicit ambition of the OAU and many African nations, the relations between white minority regimes and other African regimes are not particularly relevant for the model framework below.

[10] I could have investigated other reciprocal strategies, which are less strict than the grim-trigger in the sense that they allow for cooperation after a certain period of time after a breach. Examples are tit-for-tat and other “intermediate punishment strategies” (McCarty and Meirowitz, 2007:256-60). The main logic is, however, the same as in grim-trigger games: Credible threats of future punishment can induce actors to forego short-term gains from breaching cooperation. There are therefore SPNEs where all parties cooperate also when “milder” strategies than grim-trigger are played, but the parameter requirements for cooperation are more demanding.

[11] The model could have been made more realistic by assuming that actors are unable to intervene in every period. The possibility of intervention could be contingent on several factors, such as national and international political climate, availability of resources, readiness of the army, etc. This could be modeled through an exogenous probability of opportunity to intervene. This adjustment would have made the mathematics more complex, but the main result is that intervention would be rational for a broader set of values of p and β. The reason is that a breach of cooperation would not with certainty lead to intervention in the breacher’s own country in the next period(-s). This would lower the probability of being thrown out of office in subsequent periods and the expected cost of intervening would go down. The comparative statics related to how increases in p and β affect the likelihood of intervention would, however, be qualitatively similar to those from the model presented.

[12] There could also be other effects that are not captured by the rational choice framework presented here. If leaders meeting in the OAU developed a certain extent of “community-feeling”, where the leaders cared for one another’s well-being, or if the OAU-norms were internalized cognitively, the predicted relevance of the OAU for keeping the African peace would be even stronger than predicted by the framework above.

[13] Lemke (2003) suggests that if taking into account the many non-state actors, such as guerrilla groups, in Africa, one might come to different results. This would blur the distinction between civil and interstate war. Also, when taking into account such actors, one would not only increase the number of relevant wars, but also relevant units, and this would at least partly offset the suspected increase in the frequency rate.

[14] Data are taken from Maddison (2006) and the Polity IV database. The Polity score ranges from -10 to 10, with 10 being very democratic.

[15] Some of the most known examples are the Thirty Years’ War, The Nine Years’ War, The Great Northern War, The War of the Spanish Succession, The War of the Quadruple Alliance, The War of the Austrian Succession, The Seven Years’ War and The Revolutionary Wars. Even a moderately strong country such as Sweden fought in more than 20 wars between 1600 and 1820, involving several opponents in some of these (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Swedish_wars).

[16] See for example Palmer, Colton and Kramer (2002:460-61).

[17] Indeed, Goldsmith provides some evidence for the hypothesis that ASEAN membership significantly reduced the probability of disputes, when studying an Asian sample (Goldsmith, 2007:14).

[18] Amin eventually fell due to a Tanzanian invasion, a rare example of an African dictator being ousted in this way, but Clapham argues that one could have expected intervention long before.

[19] Interestingly, Gabon, Cote d’Ivoire, Tanzania and Zambia supported Biafra under the Nigerian civil war. Even if the model above deals mainly with interstate wars, the explicit support for secessionist movements within the boundaries of one of the more powerful actors in the system runs contrary to the self-interested coordination logic (Saideman 2001:74-83). However, most African regimes supported the Nigerian government, with 36 or more votes to 4 on Nigerian government-Biafra issues in the OAU (Saideman, 2001:99). The Nigerian civil war was also particularly notable for the degree of external support for the secessionist movement, making it a “special case” in the post-colonial African context (Clapham, 1996:112).

[20] For good discussions on how the major African nations’ leaders saw it in their interest to reform the OAU and ultimately from the AU, see Francis (2006:24-31) and Dokken (2008:122-26).

[21] Saideman (2001) ran statistical tests on support of ethnic groups in other countries in the 1990s, and found that such external support was not less prevalent in Africa than other places. Saideman portraits this as a finding that the reciprocal logic utilized here has poor explanatory power in general, but the model presented here was mainly applicable from 1963 to the end of the Cold War. Moreover, support for ethnic groups is not equivalent to conducting an interstate war.

[22] See for example Raknerud and Hegre (1997).

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Trust Me If You Can: Voluntary Sustainability Programs in the Uranium Industry

- Women, Peace and… Continued Militarism? Revisiting UNSCR 1325 and Its African Roots

- “You Blaspheme, You Die”—The Rise of Anti-Blasphemy in Pakistan

- Selective Justice and Persecution? The African View of the ICC-UNSC Relationship

- Do Coups d’État Influence Peace Negotiations During Civil War?

- “Fake It Till You Make It?” Post-Coloniality and Consumer Culture in Africa