Slums are one of the major growing global challenges in developing countries. Improving slum dwellers’ living conditions is one of the targets of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) Target 11: ‘To improve the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers by 2020’ (Khalifa, 2011). Therefore, several initiatives have been launched to address the issue of slums. Different kinds of interventions are being implemented to improve slum conditions, including provision of infrastructure, housing upgrades, income generation interventions, as with supporting the informal sector, promoting good governance, and others. Some of these programmes are adopting a participatory approach in their design and implementation in order to increase their effectiveness.

This paper will examine one of the urban poverty alleviation interventions in Egypt. The first section will introduce the participatory approach. The second section will discuss the urban poverty situation in Egypt. The third section will present the Participatory Development Programme in Urban Areas (PDP) as one of the interventions addressing urban poverty in Egypt. The fourth section will evaluate the strengths and weakness of this programme. Then, conclusions will be drawn.

Participatory Approach

Participatory approaches can be described as having adoptable methodologies that are introduced to ensure people’s participation in development projects and to empower the local community to be able to control the development process (Mitlin and Thompson, 1995). The terms ‘participatory development’ and ‘participation’ refer to the same idea and are often used interchangeably. Many definitions have been coined by donor agencies. Among them is the GTZ definition (Long, 2001):

‘Participation is seen as a principle to promote initiative, self-determination and the taking over of responsibility by beneficiaries, thus representing a critical factor for meeting a project’s objectives … The term is understood as a social-political process concerning the relationships between different stakeholders in a society, such as social groups, community, policy level and service delivering institutions. In this meaning participation aims at an increase in self-determination and re-adjustment of control over development initiatives and resources’.

Participatory development approaches appeared for the first time at the end of the 1970s and in beginning of the 1980s, and they were developed as effective methods for information collection purposes. These approaches were outsider controlled, but, later, local people became perceived as important contributors to development, unlike before when they were perceived as just beneficiaries. Local communities became much more involved in the development process. Participatory approaches are widely adopted in development projects, programmes, and research, and they are often used in rural development and health programmes and projects. Over time, these methods have come to prevail in urban development programmes and projects (Mitlin and Thompson, 1995).

Urban Poverty in Egypt

Slums are commonly known in Egypt as ‘Ashwaiyyat’, which means haphazard. This word is used to refer to slums/informal areas in Egypt that are characterized by a lack of good infrastructure and services, overcrowded population, and many other forms of urban poverty. The capital city of Egypt, Cairo, has four ‘mega slums’ out of the 30 largest slums in the world. Slums in Egypt are classified under two main categories: ‘unsafe areas’ where inhabitants’ lives are subject to threat due to risks like inadequate shelter; and ‘unplanned areas’ where housing is not compliant with state building regulations (Khalifa, 2011).

The emergence of slums in Egypt started after the end of the Second World War. They began to spread in the 1960s because of rapid domestic migration from rural to urban areas (Khalifa, 2011) due to the centralization of employment in the industry and services sectors in the capital (Kipper, 2009). The informal settlements increased further during the military conflict between Israel and Egypt from 1967 to 1973, as the government stopped all public investment in the housing sector and allocated the majority of financial resources to military mobilisation. As a result, the informal sector was the only available alternative. Urbanization and the associated increase in slums was accelerated during the ‘Oil boom’ from 1974 to 1985, when the Gulf states attracted Egyptian labourers who would send remittances that were invested in the informal building sector in Egypt (UN-HABITAT, 2003; Khalifa, 2011; El-Batran and Arandel, 1998).

Different kinds of interventions have been made by the government of Egypt and aid agencies to address urban poverty issues, particularly through targeting informal areas. Two Masterplans were presented in 1965 and the 1980s that aimed at providing a good alternative to slums and stopping urban growth at the expense of agriculture lands, through the creation of new settlements. The upgrading of informal areas was another type of intervention that the state later adopted (El-Batran and Arandel, 1998). In addition, many slum-upgrading projects were implemented in collaboration with aid organizations such as the World Bank and the German Technical Cooperation (Khalifa, 2011). The Participatory Development Programme in Urban Areas was among these efforts seeking to alleviate urban poverty.

The Participatory Development Programme in Urban Areas (PDP) in Egypt

In response to the Egyptian government’s request to the German government to contribute to finding a sustainable solution for the informal areas in Egypt, the PDP was launched. This was in collaboration with the Egyptian Ministry of Planning, the German Technical Cooperation (GIZ) and the German Financial Cooperation developing bank (KFW), in addition to the Egyptian Ministry of Local Development, NGOs, and the three governorates of Cairo, Giza, and Alexandria. It is being implemented over different phases from 2004 to 2014 (PDP, 2012a; Germany-WUF4, 2012). This programme has two schemes of international cooperation: a technical cooperation scheme implemented by GIZ and a grant aid scheme by KFW (Nour, 2011).

The programme was first launched in two pilot areas: the districts of Boulaq El Dakrour in the Giza governorate and of Manshiet Nasser in the Cairo governorate. Thereon after, the programme expanded to cover the district of Helwan in Cairo (Piffero, 2010) and, then, three areas from the Alexandria governorate in 2006 (PDP, 2012b; 2012e). Overall, it aims at promoting cooperation between public administration and civil society in order to meet the urban poor’s needs. This involves supporting the Egyptian counterparts, including the involved ministers and the targeted governorates, to find and implement sustainable solutions for informal areas (PDP, 2012a; 2012e).

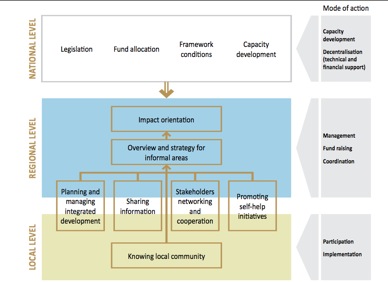

The PDP team believes that development of informal urban areas requires policy changes and a good level of decentralization that would allow for the employment of participatory approaches to be carried out. Therefore, the PDP concept is to come up with a holistic methodology that promotes the implementation of participatory methods during the upgrading of informal areas. These methods are carried out at three levels: a local level, such as municipalities and NGOs; a regional level, such as governorates; and a national level, such as ministers (Gracia Luis et al., 2010; PDP, 2012c). On the national level, PDP offers advice to ministers on how to integrate participatory development into policies; on the regional level, a number of participatory methods are presented to the municipalities and implemented in the four pilot areas; while, the problems at the local level are addressed through supporting local initiatives and building trust between local people and local administration (Germany-WUF4, 2012). The below diagram shows the three levels of intervention and each one’s mode of action:

(Source: Abdelhalim, 2010, p.15).

The overall goals of the programme are to achieve sustainable urban development, to alleviate poverty in urban areas, and to attain social inclusion, good governance and democracy. There is a set of ‘programme fields’ that are necessary to the achievement of the overall goals of the programme: upgrade of informal areas, participation, capacity development, decentralization and institutionalization, in addition to a set of principles adopted in the programme fields phase, such as local ownership, partnership, empowerment, gender equality and building trust (PDP, 2012c).

Evaluation of the Participatory Development Programme in Urban Areas (PDP) in Egypt

Strengths

The programme is having a positive impact on different levels: on the micro level, the programme is able to promote self-help initiatives through supporting a number of NGOs that empower people to become capable of finding solutions for their problems. It has also succeeded in building trust between people of informal areas and local government. On the meso level, local administrations in the pilot areas have implemented participatory approaches for better service delivery, and people have become involved in different stages of the programme. A number of departments were set up in Greater Cairo that became responsible for urban poor areas, which is a good step, according to the decentralization plans of the state. On the macro level, the upgrade of slums and addressing urban poverty issues has become a top priority for the government, and, in addition, the participatory development approach has become embedded in the state’s policy (GIZ, 2012).

Improving solid waste management was one of the positive activities carried out by the programme. It has worked on asserting that waste collection is the joint responsibility of all stakeholders, including the government, the people, and the private sector. For example, in Boulaq El Dakrour, a ‘container collection system’ was established to overcome the solid waste problems, which is a good response to one of the top needs of the district’s residents (Nour, 2011).

One of the significant successes of this programme is the provision of potable water and sewage services (Piffero, 2009), since the provision of clean water reduces the burden on the informal areas’ inhabitants, especially women. It will also reduce infection from water related diseases and improve people’s living conditions (UN-HABITAT, 2003). The programme has also succeeded in mobilizing the required funds from KFW and other stakeholders to achieve remarkable outcomes, especially in the districts of Manshiet Nasser and Boulaq El Dakrour, where physical upgrading has been carried out (PDP, 2012d).

The programme has launched a ‘Local Initiatives Fund’ project in light of the programme activities to alleviate urban poverty. This project has funded 200 initiatives, and 80% of these initiatives have been sustained. The project has created job opportunities, and the unemployment rate among youth and women has dropped (PDP, 2012d). Generally, providing funds for local initiatives has been working in accordance with the MDG recognition of microfinance as a strong tool to eliminate poverty (Gebru, 2011).

The programme has trained technical staff on GIS and information exchange systems, and possesses comprehensive information and maps for informal areas (Abdelhalim, 2010). The increasing demand of the GIS of the programme from governmental authorities and universities, for having comprehensive and accurate information on slums, has proved the importance of the GIS established by the programme (PDP, 2012d).

Apart from the tangible results of the programme, the adaptation of participatory approaches in development projects is often associated with dynamics of power relations that result in the empowerment of vulnerable groups by participating in planning, and increasing their influential power on the policy makers. This, arguably, is likely to spread throughout the whole country and, in the long run, will lead to social justice and democracy (Piffero, 2009). Thus, embracing participatory approaches in the urban context shows to be an important step towards achieving social equity (Richter and Weiland, 2012).

The involvement of all stakeholders in any development programme under a participatory approach is likely to result in cost effectiveness, owing to stakeholder contributions in different ways, either in kind or in cash. It also ensures the sustainability of the programme, as stakeholders who are involved from the beginning will be keen to keep the programme operating after donor phase-out (Piffero, 2009).

In order to ensure the sustainability and the successful replication of the programme, PDP has developed a guidance book in both Arabic and English on the PDP implementation experiences in the pilot areas. This was developed as a guidebook for decision-makers in Egypt on how to implement participatory approaches to upgrade informal areas and carry out participatory governance activities. So, the Egyptian government, in the future, can use it to replicate the pilot projects in other parts of Egypt. Furthermore, training courses on using the manual are being held for the Egyptian counterparts (Abdelhalim, 2010). Such guidelines produced on practical experience will help the government reduce urban poverty through appropriate interventions in upgrading informal areas.

Weaknesses

On the other hand, when looking at what has been pointed out as weakness of the programme, Piffero highlights that the participation concept in PDP is vague. He has found that the official documents of the programme perceive the project objectives and participation from different dimensions and that these documents do not make the priority in participatory activities clear (Piffero, 2010), which would cause confusion for the staff working on the programme. Accordingly, agreement should be made in advance on the definition of participation and the potential activities. Moreover, PDP staff do not read any critical reviews about participation, despite being given a number of donors’ manuals about it (Piffero, 2010). It is recommended that the participatory development programme team gain knowledge of the common issues that might occur, so that it can be well prepared to overcome them (Thomforde, 1998).

One of the main problems of this programme is that local government has no true willingness to adopt participatory approaches in urban development projects. It embraces participation in the programme because it perceives participation as acting as a tool to get the private sector involved, which would contribute in cash or in kind to fulfil the government’s infrastructure investment plans (Piffero, 2010). This lack of willingness is rooted back in the 1990s. The former regime in Egypt used to ignore informal areas, but they changed this strategy of ignorance in the 1990s, when a remarkable confrontation existed between the Islamists and the state. The 1992 earthquake resulted in huge damage in informal areas where Islamic organizations supported the earthquake victims who were in competition with the state. This was in addition to ‘the provocative proclamation of the Islamic Republic of Imbaba’ (an informal area in Cairo dominated at that time by Islamists), urging the government to pay much more attention to informal areas to ensure that they are kept under the control of the state (Piffero, 2009).

Based on this, the government’s (hidden) purpose seems different from the PDP’s aim: the government wanted to keep control of informal areas due to a fear of the rising power of fundamental Islamists, but, possibly, not to actually get the people involved in the development or comprehensively upgrade the informal areas’ conditions. It could be helpful if the programme staff were to employ a tool to help them to find out the real rationale behind government involvement in the project and the extent to which they will keep their promises. They could use ‘triangulation’ as a tool to find that out. Amis (1994) has highlighted the importance of using triangulation as a tool in urban contexts to check the accuracy of facts, such as government statements, from different sources.

As for target groups, PDP was set up on the assumption that informal areas represent the stereotypical image of urban poverty, i.e. where the poor are concentrated. But, the programme has ignored the fact that informal areas are varied and have different conditions according to the typology under which each of these slums comes (Piffero, 2010). There are four types of informal area in Greater Cairo. The first are those that have been built on former private agricultural land; the second type involves squatting on deserted former state land; the third type is the ‘deteriorated historic core’; the fourth type includes ‘deteriorated urban pockets’ (Sims et al., 2003). They are all different in nature. For example, informal areas that belong to the first type, former agriculture lands, have better conditions than others (Piffero, 2010). Ignoring such differences would have negative impacts on the interventions’ outcomes.

One problem is linked to people’s capability of participating. A report drafted on Citizens’ Satisfaction Surveys shows the answers of the people indicating that people are not aware of performance measurement tools and techniques, so they could not really evaluate the performance of the local administration (Piffero, 2009). Arguably, people should explained the different ways of measuring performance, in order to monitor and evaluate local government performance in achieving the desirable level of effective participation by local people. However, it should be considered that it is very difficult to measure the performance of complex activities like those carried out within participatory approaches (Holmes, 2001).

The situation of some projects also reveal how people’s voices were not given much consideration, in contrast to the programme’s concept. For example, in the Boulaq El Dakrour pilot project in Cairo, the team leader of the project has reported that physical upgrading in the district is a top priority, but, in consultation with the participants, they expressed income-generating activities to be more important for them than physical upgrades. Then, later, when a street with high congestion was chosen to be renovated and improved, shopkeepers and mini-bus drivers were harmed, as the pavement and the new method of traffic operation negatively affected the economic activities of the two groups (Piffero, 2009).

Regarding power relations, in some areas inside the Manshiet Nasser district, people have established their own governance model, which is a governance and conflict resolution council of the elders among them, known as the ‘Arab Council’ (Tekce et al., 1997). In such a system, power relations bias is likely to occur and people will not be fairly represented. It can be noticed that PDP has not addressed issues relating to power relations that would affect the programme’s objectives.

Continued involvement of people in development processes, especially when outsiders are facilitating, can raise people’s expectations that are not that easy to meet, particularly as fast as they would like, and this can result in problems (Pretty, 1995; Thomforde, 1998). This happened in the case of PDP when people’s expectations were raised and the Egyptian government did not commit to their pledge of offering funds. Consequently, GTZ had to seek another alternative, which was that KFW had to agree to fill the gap left by the Egyptian government and fund the physical upgrade of activities to meet people’s expectations (Piffero, 2010).

As for gender, despite the programme guidelines mentioning the importance of considering women’s representation in impact monitoring and evaluation (Abdelhalim, 2010), the PDP team did not give much attention to women in the early stages of the programme. Not until 2008, did they recognize that they have to include women in the programme structure. However, they did not have a clear strategy to include women nor did they place them at the top of priorities (Piffero, 2009).

Regarding the empowerment and mobilization of NGOs to represent the community in observing the development activities and becoming an active stakeholder, and also in negotiation with local government about meeting people’s needs, NGOs have failed to make the local government more responsive, transparent, and accountable to the people. The reason behind this failure is the weak capacity of many of these NGOs, which have more focused on charitable activities. They seem less interested in expanding their activities apart from charity, while the rest have shown, in the past, to have had strong links with the autocratic ruling party of the time, obstructing the means for change (Piffero, 2009).

Conclusion

This paper has presented the participatory approach as a concept, particularly in the context of urban poverty in Egypt. The Participatory development Programme in Urban Areas (PDP), which specifically seeks to alleviate urban poverty through such approaches, has been presented and evaluated in terms of its weaknesses and strengths. Despite the weaknesses of this programme, it has contributed to urban poverty reduction in some of the most well-known informal areas in Egypt, achieving many tangible results, such as with physical upgrades, GIS and the sharing of information on informal areas, funding of local initiatives, and others. As for the participatory approach in general, many drawbacks were associated with the implementation of participatory methods; however, the country’s political situation should be taken into consideration as either a hindrance or contributor to the success of participatory attempts. It is a great challenge to implement participatory approaches and to find the right tools to empower the local people in a country, like Egypt, that has to deal with such authoritarian rule and structures. Nevertheless, after the Egyptian people managed to break the wall of silence in the 25th of January Revolution, participatory approaches show to be more applicable in different areas of development. This is especially in urban poverty development, since power relations have changed, and people’s voices are more likely to be heard than before, thanks to the 25th Jan Revolution.

Bibliography

Abdelhalim, K. (2010) Participatory upgrading of informal areas: A decision-makers’ guide for action. Cairo: Participatory Development Programme in Urban Areas (PDP) in Egypt.

Amis, P. (1994) “Urban management training, action learning and rapid analysis methods”, In RRA Notes 21, Special Issue on Participatory Tools and Techniques for Urban Areas (pp. 13-16). London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

Cracia Lusi, B. Lincoln, B. Altami, C. Hassan, E. et al. (2010) Improving informal areas in greater Cairo: The cases of Ezzbet Al Nast and Dayer El Nahia. Berlin: Berlin University of Technology.

El-Batran, M. and Arandel, C. (1998) A shelter of their own: Informal settlement expansion in Greater Cairo and government responses. Environment and Urbanization. 10 (1): 217-232.

Gebru, B. (2011) Role of micro-finance in alleviating urban poverty in Ethiopia. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa. 13 (6) 165-180.

Germany-WUF4 (2012) German Technical Cooperation GTZ, Egypt. [online]. Available from: http://www.germany-wuf4.de/en/institutions/gtz [Accessed 16 April 2012].

GIZ (2012) Participation-oriented development programme in densely populated urban areas. [online]. Available from: http://www.gtz.de/en/praxis/5663.htm. [Accessed 18 April 2012].

Holmes, T. (2001) A participation approach in practice: Understanding field workers’ use of Participatory Rural Appraisal in ACTIONAID the Gambia. Working Paper number 123. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

Khalifa, M. (2011) Redefining slums in Egypt: Unplanned versus unsafe areas. Habitat International. 35: 40-49.

Kipper, R. (2009) “Cairo: A broader view”, In Kipper, R. and Fischer, M. (eds.) Cairo’s informal areas between urban challenges and hidden potential. Cairo: GTZ Egypt and Participatory Development Programme in Urban Areas (PDP) in Egypt.

Long, C. (2001) Participation of the poor in development initiatives: Taking their rightful place. London: Institute for Development Research, Earthscan Publications Ltd.

Mitlin, D. and Thompson, J. (1995) Participatory approaches in urban areas: Strengthening civil society or reinforcing the status quo?. Environment and Urbanization. 7 (1): 231-250.

Nour, A. (2011) Challenges and advantages of community participation as an approach for sustainable urban development in Egypt. Journal of Sustainable Development, 4 (1) 79-91.

Participatory Development Programme in Urban Areas (PDP) (2012a) About PDP [online]. Available from: http://egypt-urban.net/about-pdp [Accessed 17 April 2012].

Participatory Development Programme in Urban Areas (PDP) (2012b) Pilot Areas [online]. Available from: http://egypt-urban.net/pilot-areas [Accessed 17 April 2012].

Participatory Development Programme in Urban Areas (PDP) (2012c) PDP concept [online]. Available from: http://egypt-urban.net/pdps-concept [Accessed 18 April 2012].

Participatory Development Programme in Urban Areas PDP (2012d) Impact [online]. Available from: http://egypt-urban.net/impact [Accessed 18 April 2012].

Participatory Development Programme in Urban Areas (PDP) (2012e) Fact sheet [online]. Available from: http://egypt-urban.net/new-pdp-fact-sheet [Accessed 16 April 2012].

Piffero, E. (2010). ‘Best practices’ in practice: A critical reflection on international cooperation and participatory urban development in Cairo’s informal areas (Egypt). Universitas Forum, 2(1). [online] Available from: http://www.universitasforum.org/index.php/ojs/article/view/46/191 [Accessed 16 April 2012].

Piffero, E. (2009) What happened to participation? Urban development and authoritarian upgrading in Cairo’s informal neighbourhoods. Bologna: Libera La Ricerca.

Pretty, J. Guijt, I., Thompson, J. and Scoones, I (1995) Participatory learning and action: A trainer’s guide. London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

Richter, M. and Weiland, U. (2012) Urban ecology: A global framework. Haywards Heath: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Sims, D., with M. El-Shorbagi and M. Séjoumé (2003) Understanding Slums; Cairo Egypt: Case Studies for the Global Report on Human Settlements 2003 [online]. Available from: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/dpu-projects/Global_Report/cities/cairo.htm [Accessed 19 April 2012].

Tekce, B., Oldham, L. and Shorter, F. (1997) “Manshiet Nasser: A Cairo neighborhood”, InHopkins, N. and Ibrahim, S. (eds.) Arab society: Class, gender, power and development. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

Thomforde, D. (1998) “Participatory assessment for people with disabilities”, In PLA Notes 33, Special Issue on Participatory Tools and Techniques for Urban Areas (pp. 74-78). London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

UN-HABITAT (2003a) Guide to monitoring target 11: Improving the lives of 100 million slum dwellers, progress towards the Millennium Development Goals. Nairobi: UNHABITAT.

UN-HABITAT (2003b) The challenge of slums: Global report on human settlements. London: UN-HABITAT.

—

Written by: Abdelfatah Ibrahim

Written at: University of Birmingham

Written for: Dr. Philip Amis

Date written: April/2012

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Egypt’s Security Paradox in Libya

- Neo-Colonialism in Africa? An Analysis of a UK-Funded Volunteer Abroad Programme

- Egypt’s Social Welfare: A Lifeline for the People or the Ruling Regime?

- Oppressing Islamists and Domestic Insecurity in Egypt and Tajikistan

- Evaluating Russia’s Grand Strategy in Ukraine

- Gendered Implications of Neoliberal Development Policies in Guangdong Province