Storm Sandy was a natural catastrophe that came with a great cost. The hurricane devastated parts of New York and New Jersey, killing around 149 people as it swept through America and the Caribbean. Lower Manhattan, arguably the greatest concentration of financial power in the world, was plunged into darkness and normal life suspended for weeks. Indeed, Gerard Toal states that the most remarkable geopolitical development of 2012 was how climate change hit home in the United States.

One headline that caught my attention in the aftermath of the storm was not one describing the devastation or detailing the effects of climate change, but one concerning the role of the insurance market Lloyds of London in underwriting the damage caused by this natural disaster. Lloyds announced that they expected to face claims of between $2-2.5bn for the damage, making Sandy the costliest storm for the insurance sector since Hurricane Katrina.

When reading the BBC article, I was reminded of Luis Lobo-Guerrero’s latest book, ‘Insuring War: Sovereignty, Security and Risk’ (2012). There, Lobo-Guerrero articulates the importance of Lloyds in international relations since the 17th Century – specifically in relation to the maritime industry and warfare. He also highlights how the insurantial has been marginalised within geopolitical and security discourse, an absence at odds with the geopolitical significance of the insurance industry in the world today. The case study of Storm Sandy highlights how the practice of underwriting risk and uncertainty is becoming increasingly salient as the threats and risks around us become increasingly uncertain and their consequences increasingly catastrophic and expensive. Indeed, with debates surrounding climate change raging, and environmental disasters occupying the headlines with increasing frequency, insuring against natural disasters has become big business. This practice provides a fascinating alternative geopolitical scripting. Not only does it demonstrate how a hybrid or extra sovereign is created in the ‘concerted art of managing uncertainty’ (Lobo-Guerrero) but it also highlights the role that these non-state actors play in the stochastic re-interpretation of risk as opportunity and uncertainty as profitability.

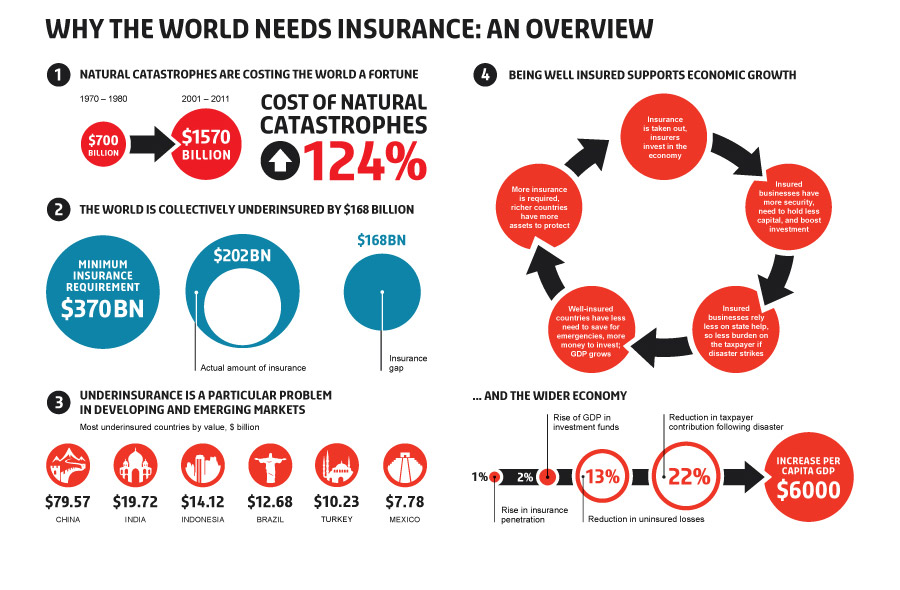

In a recent interview with Hank Watkins (President of Lloyds America), the interviewer stated that Sandy had highlighted the importance of insurance following catastrophic events. Increasing insurance cover by 1% can reduce state liability for disasters by as much as 22%, but this has yet to persuade certain Governments that this delegation of sovereignty is the way forward. Fast growing countries such as China, India and Brazil may be ensuring that they have a stake in the global market but, as figure one demonstrates they are not insuring against natural catastrophes, suggesting a reluctance to delegate sovereignty and governance away from the state. Whilst countries such as the United States and the UK spend around 4-5% of GDP on insurance, China is ailing behind at 1%. To put this into context, the 2008 Sichuan Province earthquake in China led to $125 billion of damage. Only 0.3% of this cost was carried by insurers – the rest by the Government and therefore the people.

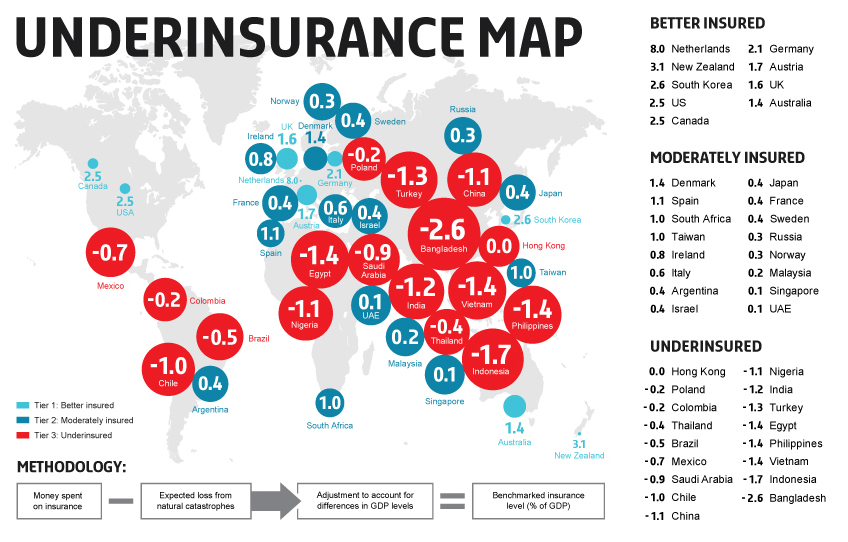

Figure 1: Map showing areas of the world that are ‘underinsured’ – or areas that are ‘at risk’ should disaster strike.

Figure 1: Map showing areas of the world that are ‘underinsured’ – or areas that are ‘at risk’ should disaster strike.

The transferral of agency and sovereignty to these private actors clearly has distinct political geographies which shape the response of individual states to natural catastrophes. A state that cannot afford insurance such as Haiti, is limited in its capacity to react to crises, whilst China’s political culture inhibits its willingness to lay off risk to a private actor. As it stands, and as the map demonstrates (with the exception of Russia), insurance is remains a liberal, Western technology of Governance, however it will be extremely interesting to see how this changes in the future.

In addition to the creation of an extra sovereign, Lloyds is also interesting in the way in which it produces risk and security as commodities. Watkins describes how brokers bring risk to the market place, creating a space in which ‘risk and capitol come together to form insurance protection’. Watkins is describing an industry that engages with insecurity and risk without seeking to challenge it. Indeed the entire industry relies on pushing frailty to optimise profitability and on the perpetual existence of the risk that it seeks to manage on behalf of states. In order to do this, risk is reduced to an actuarial model. When discussing the financial implications of Sandy, Lloyd’s Chief Executive Richard Ward stated, “the Lloyd’s insurance market remains financially strong and, while claims from this storm could still evolve over time, the market’s total exposure is well within the worst-case scenarios we model and prepare for.” This stochastic modelling of risk and the transformation of security into a set of calculated practices reduces even the most catastrophic of emergencies into an intelligible, financial figure that becomes manageable and actualised.

Figure 2: A chart from Lloyds selling insurance to the world and highlighting the ‘problem’ of under insurance.

This is an area of geopolitics and security that will no doubt continue to evolve and which warrants significant further investigation, see for instance Kevin Grove’s work on what he calls the ‘financialisation of disaster management’ in Caribbean member states. Lloyds continue to monitor and insure against a host of security problems ranging from cyber attacks to piracy, to water stewardship. The political economy of risk is enormous, cementing the role of actors such as Lloyds not as anomalies of geopolitics and security but as agents. Risk, as Lloyd’s demonstrate, is far from being a zero sum game. Ensuring a state is prepared for disaster increasingly involves insuring against that disaster. As such, the liability of a state in an emergency situation is dependent on the degree to which that state has invested in this extra sovereign to negotiate catastrophe on their behalf.

—

Rachael Squire is working towards an MSc in Geopolitics and Security at Royal Holloway as part of her ESRC funded PhD studentship on the geopolitics of rumour and conspiracy. Rachael also works part time for a Member of Parliament. Read more of GPS: Geopolitics and Security – Critical Perspectives From Royal Holloway.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Climate Change and Food Security in the Pacific

- Reducing Greenhouse Gases Is a Security Issue

- Pakistan’s Role in Western and Middle East Security

- Posthuman Security and Care in the Anthropocene

- Global Security in a Posthuman Age? IR and the Anthropocene Challenge

- ‘Firepower’ and Environmental Security in the Anthropocene