An oft-made claim is that terrorism is an effective strategy to achieve political objectives. The aim of this essay is to examine this claim and gauge whether terrorism is an effective way to achieve political goals. The essay proceeds in five sections. The first section defines terrorism and explains what measurement of effectiveness is used in this essay. Alternative definitions and measurements will be highlighted so as to underscore the appropriate and limited applicability of this essay’s findings. The second section presents prominent explanations for why terrorism is effective and the evidence to support this position. While the hypotheses are lucid and coherent, there is limited evidence to back them up. The third section explains how terrorism is ineffective and presents evidence to support this position. The hypotheses are robust and backed up by several quantitative studies. The fourth section, building on the previous two, presents possible explanations for why terrorists persist, even though terrorism is ineffective at accomplishing political goals. The concluding section summarizes the major findings and presents possible implications.

CHAPTER ONE – Definitions

The definition of terrorism is a topic in itself in terrorism studies, as it is an “essentially contested concept” inviting value judgments (Jackson et al. 2011, 100). Across academia, law, policy and politics, there is no widely agreed-upon definition of terrorism. In fact, Schmid and Jongman (1988, 5-6) found more than a hundred definitions. The purposes of this essay will be satisfied with the common three-prong definition of terrorism as politically motivated violence by non-state actors against civilians (Lake 2002, 17; Kydd and Walter 2006, 52; Jones and Libnicki 2008, 3; Stanton 2013, 1010).

There are, however, broader definitions of terrorism (Schmid and Jongman 1988, 28). As the causes, methods and effectiveness of non-state terrorists differ from those of state terrorists (Kydd and Walter 2006, 52), state terrorism will not be considered. The motivations of terrorists have to be politically motivated, which excludes those who use violence against civilians for profit-motivated, sadistic or random purposes. Civilians have to be the targets of the violence, which excludes those who try to damage physical objects or cause economic harm.

There is a blurriness to the three-prong definition though. It may be difficult to distinguish non-state actors from state actors. After all, many terrorists function in anarchic environments, sometimes providing the most hierarchy available in a given territory and at other times even becoming state actors. Terrorists may also receive support from states. The distinction between civilians and non-civilians can also be blurred, as some would charge that citizens who comprise the support system of a military cannot truly be separated from armed soldiers (Held 2008, 19-21). The true motives of groups can also be complicated to gauge, as sadism and profit motives may be shrouded in political claims (Mueller 2000).

How does one determine the effectiveness of terrorism? According to the LA Times, pronouncements that “terrorists have won” had appeared hundreds of times in US newspapers and magazines less than two months after 9/11 (2001). In this context, the phrase usually referred to how the terrorist attacks themselves, public fears, or the heavy-handed response of the government constituted a victory for the terrorists. However, fear, provocation and the terrorist attacks themselves are merely a means to an end, not an end in itself.

When terrorism is considered as a means to an end, effectiveness takes on different meanings. Some academics take into account the distinct motives of individuals within terrorist organizations to gauge the effectiveness of terrorist organizations (Krause 2013, 272). In this way, terrorism may be considered effective if it accomplishes utility for its members. The ongoing survival of the organization may also constitute effectiveness, as terrorism helps an organization pursue resources and support to keep itself going (Krause 2013, 272). While individual and organizational motives are important to understand the functions of terrorist organizations, this essay solely concerns effectiveness as the accomplishment of stated political objectives. This means that a terrorist organization like the Shining Path, which is still active and which may bring utility to its members, will not be considered effective unless it fulfills its stated political objective, which is to establish communism in Peru.

CHAPTER TWO – The Effectiveness of Terrorism

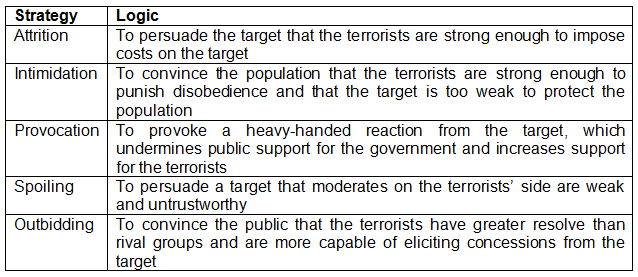

In the wake of 9/11, scholars tended to emphasize the effectiveness of terrorism (Lake 2002, Pape 2003, 2005, Kydd and Walter 2006). Of course, if one relies on the assumption that individuals are rational and that they calculate the potential benefits of terrorism versus its costs (Stanton 2013, 1010), it follows that those who choose terrorism do so because they figure out that it is effective (Pape 2003, 344). The strategic logic that the terrorists work under is to impose costs on a government so as to induce it to make concessions or provoke it to retaliate. Whatever action the government takes, the terrorists would improve their bargaining position as they received concessions or suffered retaliation, which would improve the public’s support of the terrorist cause (Lake 2002, 19-20; Pape 2005, 28: Kydd and Walter 2006, 50). Likewise, inaction undermines the government’s support as it would be incapable of protecting its citizens, a prime purpose of the state. David Lake suggests that terrorism is an effective method precisely because it forces a target to make a tricky trade-off between responding strongly to the terrorist threat and avoiding the radicalization of the public through its heavy-handed response (Lake 2002, 22). The power asymmetry between terrorists and a target makes the choice of extreme methods rational, as it is assumed that terrorists neither have popular backing nor a capability to achieve their goals through non-violent means (Lake 2002, 18; Pape 2005, 30). Any bargain between the would-be terrorists and the target is therefore unacceptable under the current distribution of capabilities, which motivates the would-be terrorists to shift the balance of power by using terrorist violence (Lake 2002, 17, 26). Kydd and Walter (2006, 51) outline five strategic logics of terrorism:

To date (April 2014), there is scant empirical evidence that suggests that terrorism is effective at achieving the political goals of terrorist organizations. The only empirical studies that support the notion that terrorism is effective are Robert Pape’s (2003, 2005). Pape (2003, 2005) is however limited to suicide terrorism, which he finds achieves “significant policy changes by the target toward the terrorists’ major political goals” about half the time. More accurately, suicide terrorism is successful as a method in 6 out of 11 campaigns in Pape (2003, 351) and in 7 out of 13 campaigns in Pape (2005). Such success rates would make suicide terrorism highly effective.

Pape’s conclusion that suicde terrorism is effective has been challenged on a few fronts though. Abrahms (2012, 368-369), for instance, notes that the success of several terrorist campaigns were exaggerated and that most of the cases examined by Pape were guerilla campaigns focused on military targets, not civilian targets. Pape’s 2003 study also suffers for its limited sample size of 11 suicide campaigns, 10 of which were directed against the same three states (Abrahms 2012, 368). Pape (2005, 258-263) excludes ongoing suicide campaigns from his analysis even though they have, on average, lasted significantly longer than the completed campaigns. If the on-going campaigns were counted as failures (given their lack of accomplishment), the success rate would be 24 percent (Moghadam 2006, 713).

The rational choice approaches suggest that suicide terrorism should be the most effective terrorist method. After all, most suicide terrorism campaigns have been fought for causes that are typically the most successful for violent campaigns. According to Cronin (2006, 13), ethnonationalist and separatist campaigns tend to last the longest. Chenoweth and Stephan (2011, 42-43) find that secessionist struggles are relatively effective. Given that sucide terrorism should be the most effective type of terrorism, Pape’s study can be seen as affirming the ineffectiveness of terrorism in general. If a 24 percent success rate for a conflation of terrorist campaigns with non-terrorist campaigns is the highest rate for the most effective type of terrorism, terrorism in general does not appear to be effective.

CHAPTER THREE – The Ineffectiveness of Terrorism

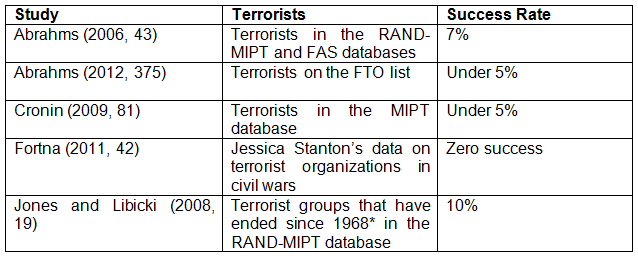

Whereas the empirical evidence is scant for the notion that terrorism is successful, several quantitative studies have shown that terrorism is ineffective (Abrahms 2006, 2012, Jones and Libicki 2008, Cronin 2009, Fortna 2011), confirming the suspicions of many pre-9/11 terrorism scholars (Laquer 1976, Crenshaw 1987, 15; Schelling 1991, 20). Abrahms (2006, 43) finds only three out of 42 cases (7 percent) where terrorists achieved their policy objectives. In comparing terrorist campaigns (civilian targets) with guerilla campaigns (military targets), Abrahms (2012, 375) also finds that guerilla campaigns are considerably more likely to achieve both partial and complete political objectives. A RAND study on the end of terrorists groups reached a similar conclusion as Abrahms (2006), and found that of all the terrorist organizations that have ended since 1968, only 10 percent were victorious (Jones and Libicki 2008, 19). While not laid out in the study itself, other authors have noted that the incorporation of active terrorist groups in the RAND data would drive the success rate down to 4 percent (Chenoweth et al. 2009, 197). Cronin (2009, 81) further confirms the ineffectiveness of terrorism, as she finds that the success rate is less than 5 percent.

Page Fortna has studied rebel organizations in the context of civil wars and contrasted those that used terrorism with those that did not. She finds no instance where a terrorist rebel organization achieved victory in a civil war (2011, 42). Rebels were also less likely to achieve peace agreements (which she interprets as a significant concession in favor of the terrorists) when terrorism had been used (2011, 42-43). Fortna’s study demonstrates, perhaps, the accuracy of Hannah Arendt’s claim that while “violence can destroy power; it is utterly incapable of creating it” (1970, 56). Terrorism has also been studied in the context of hostage negotiations. Gaibulloev and Sandler (2009, 751-752) and a forthcoming study by Abrahms and Gottfried have found that hostage takers are less likely to be accommodated if they harm their captives, which suggests that there is something about violence against civilians that makes governments less conciliatory.

The aforementioned studies find that terrorism is unsuccessful in general (See Table 1), in special circumstances and that terrorist campaigns are less effective than violent campaigns targeting mainly military personnel. While Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan do not study terrorism specifically, their study of nonviolent campaigns – which finds that nonviolent campaigns are twice as likely to achieve the partial or full achievement of goals than violent campaigns (Stephan and Chenoweth 2008, 8; Chenoweth and Stephan 2011, 40-41) – suggests that terrorist campaigns are also less effective than nonviolent campaigns.

Intriguingly, even when terrorists succeed, “in most cases, terrorism had little or nothing to do with the outcome” (Jones and Libicki 2008, 33) and “may actually have set back the broader cause” (Cronin 2009, 82). Even when terrorism directly sets a chain of events into action that allows them to achieve their goals, the reason for the success may lie in bizarre circumstances rather than the strategic rationales outlined in chapter 2. For example, the 2004 Madrid train bombings are often mentioned as a prominent case for how effective terrorism can be (Rose and Murphy 2007). Three days prior to the Spanish general elections, terrorists caused more than 2000 casualties, including 191 deaths (de Ceballos et al. 2005). Within those three days, the sitting government lost the lead that it had consistently held in opinion polls and ultimately lost the election. Many have consequently assumed that public fears and the demand for concessions allowed the terrorists to achieve their goal. However, it was not necessarily public fear or a demand for concessions that caused the shift. Some analysts would instead explain the shift by the uniquely incompetent handling of the terrorist attacks by the government, which publicly and incorrectly maintained that ETA had been responsible for the attacks (Gordon 2004).

Table 1.

* According to Chenoweth et al. (2009, 197), the incorporation of all terrorist groups in the RAND study (including active terrorist groups) would push the success rate down to 4%.

There are numerous reasons for why terrorism fails. In short, terrorism communicates poorly, precludes broad participation, induces the public to fight back rather than surrender, and empowers governments to respond with force.

First, terrorism is a bad communicative strategy. As Abrahms (2006, 56) argues, the target of terrorism may often remain ignorant of terrorist demands, even believing that terrorism is an end in itself. In some cases, educating the public regarding the terrorists’ demands is difficult, because the demands are changeable and many (Abrahms 2008, 102). In other cases, terrorists may carry out anonymous attacks, making it impossible to address their demands. Ignorance of terrorist demands consequently makes the population less concilliatory and more likely to support policies that eradicate the terrorist threat. As far as signals go, terrorism may also signal impotence and decline, as the group has to resort to underdog tactics (Fortna 2011, 20). Consequently, people on the sidelines will be less likely to join a terrorist organization, as it appears unlikely to bring them utility. Contrary to what early anarchists may have thought, terrorism does not appear to be “the most popular, the most potent, and the most irresistible form of propaganda” (Bakunin quoted in McMillan and Cavoli 2008, 24).

Second, terrorists fail to achieve the appropriate reaction among the population. Given the communicative failure of terrorism, the public may ignore or misunderstand the demands of terrorist organizations. No matter how they understand them, Abrahms (2012, 383) argues that the extremeness of the methods used to elicit political change signals inherently extreme political intentions. So rather than raise awareness over grievances and make the them appear legitimate, terrorism makes them look extreme. Stephan and Chenoweth (2008, 8-9) argue something similar, as they suggest that terrorism decreases the legitimacy of movements, making them less likely to attract domestic and international support. Chenoweth and Stephan (2011, 160) back this up by showing that nonviolent movements are much more likely to attract support from the international community (in the form of sanctions targeting regimes) than violent movements.

Even if the public supports the terrorist cause, there are significant moral hurdles that participants would have to cross relative to guerilla or nonviolent movements. They may tacitly support terrorism but would they be willing to kill civilians? Not necessarily. This precludes broad active participation. Kalyvas (2004, 105-106) also argues that the incentives for supporting a group decreases as the group resorts to indiscriminate violence, as their support will not protect them from the indiscriminate nature of the violence. Terrorist movements therefore forgo various mechanisms that Chenoweth and Stephan (2011, 48) argue greater levels of participation bring, such as “enhanced resilience, higher probabilities of tactical innovation, expanded civic disruption (thereby raising the costs to the regime of maintaining the status quo), and loyalty shifts involving the opponent’s erstwhile supporters, including members of the security forces”.

Kalyvas also argues that the perception that terrorists impose “unfair and immoderate” punishments makes people more willing to resist them (2004, 115). Short of inducing the population to make concessions, the revulsion arguably makes them more determined to fight those who resort to terrorist violence, empowering political leaders who are opposed to compromises with terrorists (Abrahms 2008, 102). Several studies show how terrorism boosts support for rightwing parties, which are the least likely to make concessions and most likely to promote stiff counterterrorism. Berrebi and Klor (2006, 924) find this effect in Israeli politics, Chowanietz (2011, 684-685) finds it in France, Germany, Spain, the UK and US, and a forthcoming study by König and Finke finds that terrorist attacks allow Germans to overcome intra-coalition and bicameral conflict to enact counterterrorist legislation.

Government repression can also be justified to the domestic population and international community with more ease when a government faces terrorists instead of guerillas or nonviolent campaigners (Stephan and Chenoweth 2008, 12; Chenoweth and Stephan 2011, 154). The notion that heavy-handed government repression radicalizes the affected populations also seems exaggerated. The drone campaign in the tribal regions of Pakistan has been presented as a case where the responses of governments to terrorism strengthen terrorists rather than undercut them (Boyle 2013, 12). While the drone campaign invokes revulsion among Pakistanis – intriguingly, the Pakistanis most opposed to the drone campaign are those who are the furthest away from the drone strike areas (Shinwari 2012, 89) – there is scant evidence that drone attacks increase terrorism or recruitment. Johnson and Sarbahi (2014) find that drone strikes are associated with decreases in the incidence and lethality of terrorist attacks. While the authors do not show how drone strikes affect the recruitment of terrorists, the fact that there is a substantial decline in terrorism could suggest that the vocal opposition to drone strikes is not necessarily being converted into strength for the terrorist organizations.

Governments are unlikely to make concessions to terrorists for several reasons. Cronin (2006, 27-28) suggests that public support for terrorism may be undermined due to fears among the population of government retaliation. Governments may also strike deals with moderate elements, which undercuts the strength of the terrorist organization. If the government resorts to repression, the repression may appear more justifiable if it targets terrorists rather than guerillas or nonviolent movements. If a government is battling terrorists that also target US interests, a forthcoming study by Boutton and Carter shows that governments receive far more foreign aid, which shows how counterterrorist efforts may gain the active support of members of the international community.

Even if a government were willing to make concessions, commitment problems prevent them. Fortna (2011, 25) suggests that terrorists are perceived as less trustworthy than other rebels and that terrorists are aware of this. This prevents both sides from trusting the other to comply with any agreement. The lack of restraint shown by terrorists also prevents loyalty shifts within the regime, as terrorists are seen as untrustworthy and seen as threatening to the lives and well-being of regime members, whether they make concessions or not. Fortna’s findings that civil wars involving terrorists last longer and are less likely to conclude with a peace agreement (Fortna 2011, 42-43) support these hypotheses.

CHAPTER FOUR – Why Do Terrorists Persist Then?

A prominent explanation for the persistence of ineffective terrorist groups is that other goals impinge on the stated political objectives of the organization. The goals of terrorist organizations can be split up into organizational goals and strategic goals. Organizational goals refer to the actions that are taken in order to strengthen the organization and ensure its survival, whereas strategic goals are about the achievement of the stated political objectives (Krause 2013, 271-272). Max Abrahms argues that the attempts to preserve the social unit often come at the expense of the official political goals of the terrorist organization. That partly explains seven puzzling facts about terrorist organizations that Abrahms (2008, 102) has presented:

- The reliance on a strategy that hardens government resistance

- The resistance to opportunities to participate in the democratic process

- The rejection of compromises

- Having many protean goals that can never be satisfied

- Anonymous attacks

- Violent competition with other groups with identical causes

- The refusal to split up after the accomplishment of political goals

There is scant evidence that all of these points apply to terrorists though (Chenoweth et al. 2009, 180-186). Jones and Libicki (2008) and Cronin (2006, 17-18; 2009), for instance, note that terrorists do, in fact, give up terrorism and become part of the political process in numerous instances, which shows that terrorists are both capable of compromising and that they disband after being victorious. Anonymous attacks can also serve the terrorist organization’s cause, for instance through spoiling (Kydd and Walter 2002). Other points are valid though. The fact that terrorist organizations compete with other groups with similar causes illustrates the need to ensure the survival of the organization over the achievement of the movement’s goals. Nemeth (2013, 349) supports the outbidding thesis as he finds that terrorist violence is more common when there is greater political competition. The unattainability of goals and the endless and changeable lists of them also supports the notion that terrorists are on an individual level motivated by something other than the accomplishment of political change. On an organizational level, this means that the lists of protean goals ensures the viability of the terrorist organization, as it will never achieve all of the stated goals and can therefore continue indefinitely. Whereas terrorism is ineffective at accomplishing political goals, Abrahms (2012, 366-368) notes that a consensus finds that terrorism is effective in furthering the organizational goals.

On an individual level, terrorists may perceive terrorism to be an effective strategy for accomplishing goals. After all, prominent terrorism scholars assumed it was, so why would not some would-be terrorists? Abrahms and Lula (2012) support the notion that terrorist leaders may, at least, be motivated by a genuine perception that terrorism is successful. They argue, however, that this is a result of the “demonstration effect”, whereby the use of certain tactics score highly visible victories. As violent anti-colonial struggles by asymmetric non-state actors were perceived to be a successful tactic, would-be terrorist leaders took it as indicative of the effectiveness of terrorism (Abrahms and Lula 2012, 50). However, most of the anti-colonial campaigns were not terrorist campaigns. They were violent campaigns targeting mainly military forces (Abrahms and Lula 2012, 52). To back this up, they note that all of the 65 campaigns that Al-Qaeda has invoked as analogies to predict their own success were guerilla campaigns that targeted armed forces, not terrorist campaigns that targeted civilians (Abrahms and Lula 2012, 54).

If not motivated by the perception that terrorism is an affective strategy to accomplish political objectives, what are individual terrorists motivated by? Psychological approaches have proposed that would-be terrorists are prone to social isolation and identity struggles (Victoroff 2005, 22-23), which may motivate them to seek out social solidarity and ways to affirm their identity. Daveed Gartenstein-Ross tells the story of a few Western jihadists as liars, frauds and phonies. He notes how John Walker Lindh adopted the persons of a black hip-hop artist on internet forums (despite being white), Daniel Boyd falsely claimed to have been a Vietnam War veteran and Nicholas Teausant pretended to have undergone basic military training (Gartenstein-Ross 2014). Byman and Fair (2010) also note that terrorist claims to piety are often undercut by their less-than pious actions. This illustrates a need to affirm a righteous identity and a desire for social acceptance.

A terrorist organization may provide the social solidarity and image of righteousness that some individuals crave and that no other voluntary organization can provide. Abrahms (2008, 100) argues that the dangers and costs of participation in terrorism necessarily make terrorist groups more tight-knit than other groups. To back up the assertion that individual terrorists seek social solidarity rather than achievement of political goals, he cites evidence that terrorists often fail to understand the basic purpose of their organization’s political purpose (Abrahms 2008, 99), that those who have friends and relatives in terrorist organizations are more likely to join the organizations, and that interviews with terrorists show that friendship rather than ideology motivated them to join the organizations (Abrahms 2008, 97-98). This might also explain why foreign fighters cluster in areas where other terrorist groups are, as they seek out comradery and adventures (Abrahms 2008, 100-101).

Conclusion

This essay has revealed several things. First, there is scant evidence to support the notion that terrorism is effective at achieving political goals. Second, there are several empirical findings that support the position that terrorism is highly unsuccessful. Third, terrorism is a wildly ineffective method to accomplish political goals relative to non-violent campaigns or violent methods that target mainly military personnel. Fourth, while terrorism is ineffective at achieving political goals, it is effective at ensuring the survival of the organizations that use the method and it may bring its members utility. Fifth, the survival of the terrorist organization and the utility that the organization’s activities bring its members may both impede the accomplishment of political objectives and ensure the continued existence of the organization despite persistent failure in accomplishing stated political objectives.

The research into the effectiveness of terrorism can have significant implications. If terrorism rarely achieves political objectives (Jones and Libicki 2008, Cronin 2009) and is significantly less effective than guerilla campaigns (Abrahms 2006, 2012, Fortna 2011) or non-violent campaigns (Stephan and Chenoweth 2008, Chenoweth and Stephan 2011), the pronouncement of terrorism’s ineffectiveness can have consequences. After all, if terrorist organizations are created, joined and supported because it is believed that terrorism is an effective strategy to achieve political goals, the realization that it is ineffective should deter would-be terrorist leaders, foot soldiers and supporters. Furthermore, the realization that non-violent or limited forms of violence are more effective should give those who earnestely pursue political objectives alternative methods for accomplishing them.

References

Abrahms, Max. 2006. “Why Terrorism Does Not Work.” International Security 31(2): 42-78.

Abrahms, Max. 2008. “What Terrorists Really Want: Terrorist Motives and Counterterrorism Strategy.” International Security, 32(4): 78-105.

Abrahms, Max. 2012. “The Political Effectiveness of Terrorism Revisited.” Comparative Political Studies 45(3): 366-393.

Abrahms, Max and Karolina Lula. 2012. “Why Terrorists Overestimate the Odds of Victory.” Perspective on Terrorism 6(4-5): 46-62.

Abrahms, Max and Matthew S. Gottfried. Forthcoming. “Does Terrorism Pay? An Empirical Analysis.” Working Paper. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/5470265/Does_Terrorism_Pay_An_Empirical_Analysis_forthcoming_with_Matthew_Gottfried_ (accessed 3 April 2014).

Arendt, Hannah. 1970. On Violence. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Berrebi, Claude and Esteban F. Klor. 2006. “On Terrorism and Electoral Outcomes Theory and Evidence from the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 50(6): 899-925.

Boutton, Andrew & David B. Carter. Forthcoming. “Fair Weather Allies: Terrorism and the Allocation of. U.S. Foreign Aid.” Journal of Conflict Resolution. DOI: 10.1177/0022002713492649

Boyle, Michael J. 2013. “The costs and consequences of drone warfare.” International Affairs 89(1): 1-29.

Byman, Daniel and Christine Fair. 2010. “The Case for Calling Them Nitwits.” The Atlantic, 8 June. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2010/07/the-case-for-calling-them-nitwits/308130/ (accessed 3 April 2014).

Chenoweth, Erica and Maria J. Stephan. 2011. Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, E-book version. New York: Columbia University Press.

Chenoweth, Erica, Nicholas Miller, Elizabeth McClellan, Hillel Frisch, Paul Staniland and Max Abrahms. 2009. “Correspondence: What Makes Terrorists Tick.” International Security 33(4): 180-202.

Chowanietz, Christophe. 2011. “Rallying around the flag or railing against the government? Political parties’ reactions to terrorist acts.” Party Politics 17(5): 673-698.

Crenshaw, Martha. 1987. “Theories of terrorism: Instrumental and organizational approaches.” Journal of Strategic Studies 10(4): 13-31.

Cronin, Audrey Kurth. 2006. “How al-Qaida Ends: The Decline and Demise of Terrorist Groups.” International Security 31: 7-48.

Cronin, Audrey Kurth. 2009. How Terrorism Ends: Understanding the Decline and Demise of Terrorist Campaigns. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

De Ceballos, J Peral Gutierrez, F Turegano-Fuentes, D Perez-Diaz, M Sanz-Sanchez,

C Martin-Llorente and JE Fuerrero-Sanz. 2005. “11 March 2004: The terrorist bomb explosions in Madrid, Spain – an analysis of the logistics, injuries sustained and clinical management of casualties treated at the closest hospital.” Critical Care 9(1): 104-111.

Fortna, Page. 2011. “Do Terrorists Win?: Rebels’ Use of Terrorism and Civil War Outcomes.” APSA 2011 Annual Meeting Paper. Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1900697 (accessed April 8, 2014).

Gaibulloev, Khusrav and Todd Sandler. 2009. “Hostage Taking: Determinants of Terrorist Logical and Negotiation Success.” Journal of Peace Research 46(6): 739-756.

Gartenstein-Ross, Daveed. 2014. “The Lies American Jihadists Tell Themselves.” Foreign Policy, 21 March. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2014/03/21/the_lies_american_jihadists_tell_themselves_teausant (accessed 2 April 2014).

Gordon, Philip H. 2004. “Madrid Bombings and U.S. Policy,” testimony to the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. Available at: http://www.brookings.edu/research/testimony/2004/03/31europe-gordon (accessed 13 October 2013).

Held, Virginia. 2008. How Terrorism is Wrong: Morality and Political Violence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jackson, Richard, Lee Jarvis, Jeroen Gunning and Marie Breen Smyth. 2011. Terrorism: A Critical Introduction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Johnson, Patrick B. and Anoop K. Sarbahi. 2014. “The Impact of U.S. Drone Strikes on Terrorism in Pakistan and Afghanistan.” Working Paper, 11 February. Available at: http://patrickjohnston.info/materials/drones.pdf (accessed 3 April 2014).

Jones, Seth G. and Martin C. Libicki. 2008. How Terrorist Groups End: Lessons for Countering al Qa’ida. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Kalyvas, Stathis N. 2004. “The Paradox of Terrorism in Civil War.” Journal of Ethics 8(1): 97-138

Krause, Peter. 2013. “The Political Effectiveness of Non-State Violence: A Two-Level Framework to Transform a Deceptive Debate.” Security Studies 22(2): 259-294.

Kydd, Andrew H. and Barbara F. Walter. 2002. “Sabotaging the peace: The politics of extremist violence.” International Organization 56(2): 263-296.

Kydd, Andrew H. and Barbara F. Walter. 2006. “The Strategies of Terrorism.” International Security 31(1): 49-79.

König, Thomas and Daniel Finke. Forthcoming. “Legislative Governance in Times of International Terrorism.” Journal of Conflict Resolution. DOI: 10.1177/0022002713503298

Lake, David A. 2002. “Rational Extremism: Understanding Terrorism in the Twenty-first Century.” Dialog-IO 1(1): 15-29.

Laqueur, Walter. 1976. “The futility of terrorism.” Harper’s Magazine, March. http://harpers.org/archive/1976/03/the-futility-of-terrorism/ (accessed 3 April 2014).

Los Angeles Times. 2001. “A Phrase That Turns Routine Acts Into Acts of War.” LATimes.com, 27 November. http://articles.latimes.com/2001/nov/27/news/lv-terrorwar27 (accessed 3 April, 2014).

McMillan, Joseph and Christopher Cavoli. 2008. “Countering Global Terrorism.” in Strategic Challenges: America’s Global Security Agenda, edited by Stephen J. Flanagan and James A. Schear, 20-60. Dulles: National Defense University Press and Potomac Books.

Moghadam, Assam. 2006. “Suicide Terrorism, Occupation, and the Globalization of Martyrdom: A Critique of Dying to Win.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 29(8): 707-729.

Mueller, John. 2000. “The Banality of “Ethnic War”.” International Security 25(1): 42-70.

Nemeth, Stephen. 2013. “The Effect of Competition on Terrorist Group Operations.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58(2): 336-362.

Pape, Robert A. 2003. “The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism.” American Political Science Review 97(3): 343-361.

Pape, Robert A. 2005. Dying to Win: The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism. New York: Random House.

Rose, William and Rysia Murphy. 2007. “Correspondence: Does Terrorism Ever Work? The 2004 Madrid Train Bombings.” International Security 32(1): 185-192.

Schelling, Thomas G. 1991. “What purposes can ‘international terrorism’ serve?” in Violence, Terrorism, and Justice, edited by Raymond Gillespie Frey and Christopher W. Morris, 18-32. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schmid, Alex and Albert Jongman. 1988. Political Terrorism: A Research Guide to Concepts, Theories, Databases, and Literature. New Brunswick: Transaction Books.

Shinwari, Naveed Ahmad. 2012. Understanding FATA: 2011. Islamabad: CAMP.

Sprinzak, Ehud. 2000. “Rational Fanatics.” Foreign Policy, 1 September. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2000/09/01/rational_fanatics (accessed 3 April 2014).

Stanton, Jessica A. 2013. “Terrorism in the Context of Civil War.” The Journal of Politics 75(4): 1009-1022.

Stephan, Maria J. and Erica Chenoweth. 2008. “Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict.” International Security 33(1): 7-44.

Victoroff, Jeff. 2005. “The Mind of the Terrorist: A Review and Critique of Psychological Approaches.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 49(1): 3-42.

—

Written by: Sverrir Steinsson

Written at: University of Iceland

Written for: Dr. Page Wilson

Date written: April 2014

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- How Effective is Terrorism in Exerting Political Influence: The Case of Hamas?

- How Helpful is ‘Effective Altruism’ as an Approach to Increasing Global Justice?

- Does Terrorism Work?

- Terrorists Need an Ideology

- How Effective Is the SCO as a Tool for Chinese Foreign Policy?

- Failed States and Terrorism: Engaging the Conventional Wisdom