This is an excerpt from Conflict and Diplomacy in the Middle East: External Actors and Regional Rivalries. Get your free copy here.

The Middle East has been a historically contested ground for intertwined and conflicting interests. The gradual US withdrawal from the region combined with China’s growing economic interests; Beijing’s more confident stance towards foreign interactions; as well as China’s “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) initiative since 2013, have resulted in rising speculation about the trajectory of bilateral relations between China and the nations of the Middle East. Specifically, there is a rising voice arguing that China is developing a grand new Arab policy and actively pivoting towards the Middle East in order to fill the power vacuum left by US withdrawal (Ghosal 2016; Dusek and Kaiouz 2017; Luft 2016; Hayoun 2016, Romaniuk and Burgers 2016). On the other hand, there are scholars challenging the shifting nature of China’s Middle East Policy, arguing that Beijing’s policy towards the Middle East is driven by its domestic economic needs and China’s military and diplomatic involvements in the region are superficial and symbolic at best (Scobell and Nader 2016; Calabrese 2017).

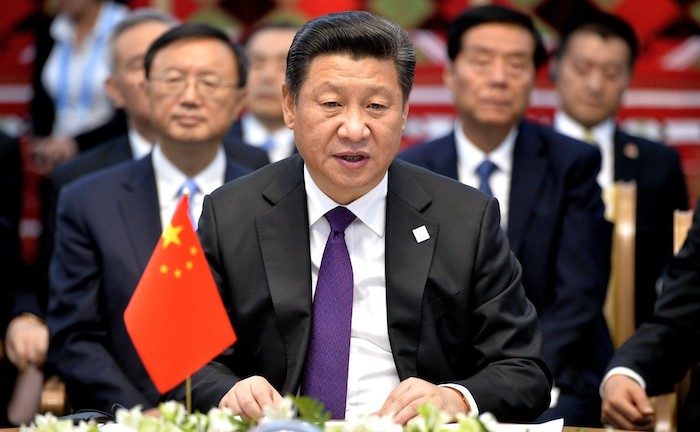

China’s engagement with the Middle East has expanded dramatically since the end of the Cold War. With China’s growing energy demands, Beijing’s economic engagement with the region has further amplified during the past years. Most recently, 2016 marked a milestone in China–Middle East relations with a series of unusual political moves by Beijing, including Beijing’s release of the first Arab Policy Paper on 13 January (State Council of the PRC 2016), Chinese President Xi Jinping’s first trip to the Middle East countries of Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Iran during January 19–23 (Xinhuanet 2016), as well as China’s self-interpretation of the trip as a new type of international relations and diplomacy (Xinhuanet 2016; Xu 2016). These prominent signs of change seem to suggest a changed policy towards the region. They also raise a series of questions: Is China’s Middle East Policy going through drastic changes? Towards which direction is it evolving? To what extent is Beijing pivoting towards the Middle East? Is Xi Jinping’s China actively filling the power vacuum in the Middle East left by the US? Or has Beijing primarily continued its non-interference foreign policy? And finally, what does the Middle East mean to today’s China politically, economically, and strategically? This research explores these questions via archival research and analysis of government documents and the official rhetoric of the Xi Jinping administration. By exploring the existing literature, government documents/data, official Xinhua news reports, as well as speeches/talks delivered by Chinese government officials since 2013 specifically, the research maps out the dynamics of China’s engagement with the Middle East in a broader historical context.

The History of China–Middle East Relations

Despite over 2000 years of recorded history of bilateral engagement and interactions (Gao 2015; Scobell and Nader 2016), the exchange between the two entities has not always been smooth (Ma 2010). While the 1955 Bandung Asian–African Conference first kindled bilateral interactions between the People’s Republic of China and Middle Eastern countries such as Egypt, Syria, and Yemen, the Sino–Soviet split (1956–1966) and the Chinese Cultural Revolution disrupted relations (Olimat 2014). The two parties did not resume interactions until the early 1970s when the PRC was admitted into the United Nations (UN), thus resulting in the establishment of diplomatic ties between China and Iran, Kuwait, Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey (Shicor 1979). Under Deng Xiaoping, China’s diplomatic success reached another height as Beijing established diplomatic relations with all Middle Eastern countries in the 1990s. China’s rapidly growing economy offered products and opportunities. Middle Eastern countries, in turn, helped China fulfill its soaring need for energy and resources.

Although the Middle East became deeply embroiled in military conflicts fueled by the US at the beginning of the new millennium, relations between China and the region remained strong. With growing economic interests, China created the China–Arab States Cooperation Forum (CASCF) in 2004, which aims to “serve as a platform for exchanging views between China and Arab nations, promoting cooperation in politics, the economy and trade, culture, technology and international affairs while advancing peace and development” (Xinhuanet 2016). Since then, the forum has functioned as an important mechanism facilitating trade and cooperation between the two sides. Despite twists and turns in bilateral relations, Beijing has consistently upheld its official rhetoric of non-interference and non-intervention in regional internal affairs. This staunch neutrality, however, was put to the test in recent years due to significant changes in both China’s domestic politics and the regional situation in the Middle East.

Recent Dynamics in China–Middle East Relations

With Xi’s rise to power, China formally departed from Deng Xiaoping’s world view of “keeping a low profile”. The One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative proposed by Xi in 2013 was believed to substantively “expand China’s economic and diplomatic influence over the Middle East at the expense of the US supremacy” (Chaziza 2016; Xinhuanet 2016; Sharma and Kundu 2016). China’s growing political and economic interests in the region increased the need and urgency for China to enhance its engagement with the Middle East. Additionally, rising domestic challenges such as domestic Islamic terrorism and economic rebalancing also push China towards greater engagement and closer cooperation with the region. As China acquired the status of a newly self-conscious power under Xi (Dittmer 2015), this newly assumed and more assertive national identity also raised expectations for Beijing to shoulder more responsibilities in regional and international affairs, thus putting pressures on China to participate in more substantive ways in constructing peace in the Middle East. As the research reveals, China’s engagement with the Middle East under Xi has proliferated in both volume and significance and Beijing’s interactions with the region have expanded economically, diplomatically, militarily and culturally.

Economic Engagement

According to the US Energy Information Administration, China overtook the US as the largest net importer of crude oil from the Middle East in 2013 and it again surpassed the US by becoming the largest importer or crude oil worldwide in 2017 (EIA 2018). Although China has attempted to diversify its sources of oil from non-OPEC countries over the past decade, by 2030, the Middle East is expected to account for 70 percent of China’s energy needs (Olimat 2014). As significant as this statistic is, China’s economic engagement with the Middle East goes far beyond the energy field. Driven by China’s OBOR initiative and facilitated by the CASCF, China is engaging the region in multiple areas. In 2014, China proposed a “1+2+3” model of cooperation with the Middle East in the 6th Ministerial Conference of the China–Arab Forum. The proposal expanded bilateral cooperation from energy into diverse areas such as infrastructure, trade, and investment – as well as high tech cooperation in nuclear energy, space satellites, and other new energy initiatives. As the proposal materialized, China’s investment in the region soared (Arun 2018). China’s investment in Iraq’s oil industry and its bilateral trade with Saudi Arabia are among the most noteworthy (Reuters 2015; State Council of the PRC 2015; Jin 2016; Erdbrink 2016; Ghosal 2016). In addition to an extensive cooperation on oil and energy, China and Saudi Arabia vowed to develop comprehensive strategic partnerships and cooperation in the fields of aerospace, finance, and nuclear power. In 2016 the two states established a bilateral mechanism, the China–Saudi Arabia High Level Joint Committee to facilitate the comprehensive partnership. In all, the whirlwind diplomacy conducted during Xi’s first trip to the Middle East in 2016 secured no fewer than 50 cooperation agreements and memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with Middle East countries (Perlez 2016; Su 2016; Xinhuanet 2016).

China has also expanded economic cooperation with Palestine and Israel in recent years. Chinese officials including President Xi Jinping, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, as well as foreign minister Wang Yi invariably reiterated China’s commitment to deepening economic cooperation with both Israel and Palestine during official visits paid by Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Palestine’s President Mahmoud Abbas in 2017 (Foreign Ministry of the PRC [FMPRC] 2017). Specifically, China announced its commitment to actively speed up negotiations on a China–Israel free trade zone. The two sides discussed deepening their collaboration in multiple areas ranging from advanced technology, clean energy, and communications. Israel also extended an invitation for China to participate in infrastructure construction projects in Israel (FMPRC 2017). With regard to Palestine, China committed to assist Palestine in increasing its self-help capacity by building industrial parks, developing solar power stations, and increasing investment and economic aid (FMPRC 2017). Both Israel and Palestine confirmed their eagerness to jointly build OBOR with China (FMPRC 2017).

The OBOR is expected to be the driving force of closer China–Middle East ties. At the time of writing, the Xi administration has stated that over 100 countries have welcomed the OBOR initiative and over 40 countries and international organizations have signed bilateral agreements with China to jointly build the OBOR. Moreover, China’s investment in the countries along the OBOR route already reached $50 billion at the beginning of 2017 (N.D. 2017). As of now, major regional powers including Israel, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Iran all stand ready to jointly build the OBOR with China and many of these countries have taken practical steps to be part of this grand initiative. In September 2017, Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif commented during a visit to Beijing that Iran hoped to conduct integration with the Chinese side as soon as possible (FMPRC 2017). In late 2017, King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud of Saudi Arabia also expressed Saudi Arabia’s eagerness to integrate Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 with the Belt and Road Initiative through the China–Saudi Arabia High Level Joint Committee in Beijing.

Diplomatic Engagement

Prominent Chinese diplomatic activities in the Middle East are commonplace during the Xi administration, with China playing an increasing role of peace mediator or peace broker for major conflicts in the region. China mediated the Yemen Crisis by hosting talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia during 2015–2016 (Middle East Observer, 2016). In December 2017, China hosted the “Palestinian–Israeli Peace Symposium” (Xinhuanet 2017). In May 2018, China also hosted the International Symposium on Syrian issues (FMPRC 2018). As part of the mediation efforts, China’s special envoy to the Middle East made extensive visits to relevant countries to facilitate peace talks and political settlements during both the Libya and Syrian crisis (FMPRC, 2017). With regard to the Iran Nuclear Crisis, Beijing both facilitated and supported the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) via its bilateral consultation mechanism with Iran (FMPRC 2017).

Above and beyond being a peace mediator or broker, China also attempts to actively shape affairs by being more assertive in the UN Security Council – including by using multiple vetoes on the Syrian crisis – and by sharing Chinese wisdom in managing Middle East conflicts. After initially sharing a four point proposal in resolving the Syrian crisis in 2012, Chinese officials have repeatedly reiterated the “China approach” which emphasizes political, inclusive, and transitional means of managing the Syrian crisis. Beijing also made timely adjustments to its Syrian approach as the situation in the country changed. For example, in November 2017, Chinese Foreign Minister, Wang Yi, proposed counter-terrorism, dialogue and reconstruction as three key points for solving the Syrian crisis (FMPRC 2017).

In the case of the Israel–Palestine Conflict, Xi proposed a four point approach to Mahmoud Abbas in July 2017 promoting political settlement of the issue. The four points are advancing the Two-State Solution based on 1967 borders; upholding the concept of common, comprehensive, co-operative and sustainable security, immediately ending Israeli settlement building, taking immediate measures to prevent violence against civilians, and calling for an early resumption of peace talks; coordinating international efforts to put forward peace promoting measures that entail joint participation at an early date; as well as promoting peace through development and cooperation between the Palestinians and Israel. Additionally, Xi also proposed a China–Palestine–Israel trilateral dialogue mechanism shortly afterward (FMPRC 2017). Throughout the process of mediation between Palestine and Israel, China has consistently upheld the Two-State Solution and supported the establishment of a Palestinian state enjoying full sovereignty and independence on the basis of the 1967 borders with East Jerusalem as its capital (FMPRC 2017). More widely, China has engaged in political consultations with a wide range of states and organizations like Turkey, Iran, France, Israel, the Arab League, the EU, the BRICS, as well as the UN in mediating peace in the Middle East.

China under Xi has clearly augmented its engagement with the region diplomatically at an unprecedented level. This diplomatic activism, however, should not be exaggerated as a hegemonic Chinese aspiration to replace the US in the Middle East. The very fact that China has consistently maintained its neutral position towards the Yemen Crisis, the Palestine–Israel Conflict, and the Syria and Libya Crises clearly shows China’s efforts to avoid the interventionist US path in the region. On multiple occasions, Chinese officials emphasized that China had no private interests in the Middle East and the country stood ready to play a constructive role in the Middle East by upholding an unbiased and objective position on the regional affairs. In Xi’s speech to the Arab League in 2016, he reiterated this:

Instead of looking for a proxy in the Middle East, we promote peace talks; instead of seeking any sphere of influence, we call on all parties to join the circle of friends for the Belt and Road Initiative; instead of attempting to fill the “vacuum”, we build a cooperative partnership network for win–win outcomes (Xinhua 2016).

In the same speech, Xi stressed that China would strive to be constructor of the Middle East peace, promoter of Middle East development, propeller of Middle East industrialization, supporter of Middle East stability, as well as a partner of Middle Eastern public diplomacy (N.D. 2017). The following year, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, further reiterated Beijing’s stance at a joint press conference held with the Foreign Minister of Palestine:

China has no geopolitical consideration in its role in the Middle East, nor intention to make a balance with any other country. We always propose historical justice and uphold international righteousness in the Middle East issue. China welcomes any country outside the region including the US that wants to support the Middle East more, and give more attention to the Palestine–Israel issue (FMPRC 2017).

Wang Yi further expounded China’s position at the joint press conference with the Jordanian Minister of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates, Ayman Safadi, three months later:

China’s role in the Middle East issue is definitely a constructive one. China pursues no geographical interests and seeks no sphere of influence in the Middle East, and will not be partial to any party. The Chinese side stands ready to adhere to the objective and impartial stance to push forward the political settlement of regional hotspot issues (FMPRC 2017).

Military Engagement

Besides flourishing economic and diplomatic activities, China has engaged the region militarily via arms sales, the presence of its navy forces, its participation in peacekeeping, and its collaboration with the regional anti-terrorism fight (Olimat 2014). Driven by the security challenges posed by extremists among the Chinese Muslims in Xinjiang, China passed its first anti-terrorism law in December 2015 paving the way for an active military involvement in anti-terror missions at home and abroad. Under the framework of bilateral cooperation, China actively supported Iraq in its fight against ISIS by sharing intelligence and providing training (Chaziza 2016). Additionally, military cooperation with Iran also expanded when the two countries held a joint military exercise in the Persian Gulf in June 2017 (South China Morning Post, 2017). China also held a joint anti-terrorism military exercise with Saudi Arabia in Chongqing, China. To contain the threat posed by the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), China also actively sought enhanced counter-terrorism cooperation with Turkey (Reuters 2017). On top of this, Xi earmarked $300 million in aid to the Arab League in 2016 to enhance the capacity of the member states in preserving regional stability (N.D. 2017).

China’s increased military collaborations across the Middle East went hand-in-hand with Xi’s initiative to modernize China’s military and increase Chinese military participation in global governance. Since Xi took office in 2013, he has emphasized the importance of modernizing the Chinese military in general and strengthening the navy in particular (N.D. 2017). China’s military modernization is proceeding faster than expected to the extent that “it is China and no longer Russia, that increasingly provides the benchmark against which Washington judges the capability requirements for its own armed forces” (Marcus 2018). As part of comprehensive efforts to improve military management and capacity, China has formed a Ministry of Veterans Affairs in March 2018 and has committed itself to more extensive financial and personnel participation in UN peacekeeping endeavors. Despite the burgeoning military collaboration with Middle Eastern countries on the anti-terrorism front, it is noteworthy that China remains reluctant to align with any state militarily in the region. According to China’s Foreign Minister, Wang Yi, “China will not take part in any coalition fighting ‘terrorist groups’ in the Middle East, but will do its fair share in its own way.” (Irish 2016).

Cultural Engagement

China has vigorously promoted cultural exchanges with the Middle East under the Xi Administration. These efforts were primarily driven by China’s OBOR propaganda campaigns on the international stage. As shared by Xi Jinping at the Arab League in 2016 – to facilitate exchange of ideas and talents, China and the Middle East committed to engage in various cultural and academic initiatives such as the China–Arab Year, a China–Arab Research Center, the “Silk Road Book Translation” program, exchange programs for scholars, and scholarships to Arab students and artists to visit and study in China. China announced its plan to jointly translate 100 classic books into both Arabian and Chinese. China also promised to support an exchange of 100 scholars and experts annually, to provide 1,000 training opportunities for young Arab leaders, and invite 1,500 leaders of Arab political parties to visit China. Additionally, China committed to provide 10,000 scholarships and 10,000 training opportunities for Arab states and organize mutual visits for 10,000 Chinese and Arab artists in the same year. Finally, China initiated cooperation between 100 cultural institutions from both sides. By 2016, the number of students sent to China had exceed 14,000 and there are currently nearly a dozen Confucius Institutes in Arab states (CRI, 2016).

With these heightened cultural exchanges emerging between China and the Middle East, a mutual understanding among the people from the two sides is growing. The public sentiment about China, however, is volatile in the Middle East. There were difficult feelings about China when Beijing supported regimes like Syria and Iran. In the Syrian case, many people took to the streets to protest against the Chinese government in the wake of China’s veto of the UN resolution on Syria. In addition, the public remained skeptical about China’s alleged sincerity in promoting economic development in the region (Olimat 2014). With regard to Iran, Middle East public opinion was by no means positive about the country. Despite an overall positive perception of China among the wider public in the Middle East, China’s influence in the region was almost invisible in the eyes of the people of the region in comparison to the US, Russia, and Turkey as revealed in a 2017 PEW survey (Fetterolf and Poushter 2017).

Conclusion

There are prominent signs of both changes and continuities in Beijing’s engagement with the Middle East under Xi Jinping’s administration. It is evident that both Beijing’s interests and its stakes in the Middle East have been considerably augmented since 2013 when the Middle East, ceased to be a peripheral interest. With China’s soaring trade volume, heavy investment in the region, proactive diplomacy as peace mediator, expanded military interactions, as well as Beijing’s keen projection of its soft power – China undoubtedly became a more visible player in the region. This heightened presence nonetheless reflects the status of the country as a newly self-conscious great power that is becoming more assertive and confident on the international stage. As China further enters into practical cooperation with Middle East countries along the OBOR route and Beijing recalibrates its foreign policy in line with its status as a great power, it is likely that that Beijing’s involvement in the region will deepen in the years to come.

However, China’s enhanced economic, military, cultural, and diplomatic activism in the Middle East should not be exaggerated. The neutrality Beijing exercises when working with regional conflicts, its pronounced position of not finding proxies in the region, and its commitment to not align with any parties even in the antiterrorism coalition – as well as its insistence on political settlements of all regional conflicts – invariably confirmed China’s intention to avoid deep entanglements in regional affairs. Instead, Beijing is more enthusiastic about promoting its own model of engaging the Middle East. China seems to hope that by promoting regional economic prosperity under the framework of the OBOR and also advocating political settlements of the region’s conflicts, it will foster stability and cement its power and influence as a newly emerged great power with minimum cost. However, the OBOR will not be implemented smoothly without a proper settlement of the military conflicts in the region. As China continues to push for its OBOR initiative, the more deeply intertwined interests between China and the region – and the rising international expectations for China thereafter – will likely push Beijing to take a more decisive stand. Beijing will have to articulate its Arab Policy and define its interests in the region much more clearly. Before this happens, Beijing is likely to continue to walk the tightrope as a wary dragon between symbolically involving itself in Middle East conflicts and simultaneously protecting its expanded economic interests in the region. China’s new grand Middle East Policy is yet to emerge. However, Beijing’s friendly relations with the governments of the region, its rising international influence, and its more assertive foreign policy will – if managed well – combine to enable China to play a more substantial role in the region.

References

Arun, Swati. 2018. “China” in P.R. Kumaraswarmy and Meena Singh Roy eds, Persian Gulf 2016–2017: Indian’s Relations with the Region. New Delhi: Pentacon Press.

Calabrese, John. 2017. “China’s Role in Post Hegemonic Middle East”. Middle East Institute. May 01, 2017. http://www.mei.edu/content/article/chinas-role-post-hegemonic-middle-east.

Chaziza, Mordechai. 2016. “China’s Middle East Policy: The ISIS Factor”. Middle East Policy, Vol. XXIII, No. 1, Spring.

Dittmer, Lowell. 2015. “China Dream, China World”. In the China Dreams: China’s New Leadership and Future Impacts edited by Chn-Shian Liou and Arthur S. Ding, 33–56. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co.

Dusek, Mirek and Maroun Kairouz. 2017. “Is China Pivoting towards the Middle East?”, World Economic Forum, April 4, 2017,https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/04/is-china-pivoting-towards-the-middle-east/.

Erdbrink, Thomas. 2016. “China Deepens its Footprint in Iran after Lifting of Sanctions”. The New York Times, 24 January 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/25/world/middleeast/china-deepens-its-footprint-in-iran-after-lifting-of-sanctions.html.

Fetterolf, Janell and Jacob Poushter. “Key Middle East Publics See Russia, Turkey and US All Playing Larger Roles in Region”. Pew Research Center, December 11, 2017. http://www.pewglobal.org/2017/12/11/key-middle-east-publics-see-russia-turkey-and-u-s-all-playing-larger-roles-in-region/.

Gao, Zugui. 2015. “China-Middle East Relations since the Middle East Crisis”. Arab World Studies, No. 1. 14–22. http://www.mesi.shisu.edu.cn/_upload/article/04/29/01adacbb411085376090ae9285d7/ca7422ce-07a4-48d7-a98a-e9a46607695f.pdf

Ghosal, Debalina. 2016. “China Pivots to the Middle East and Iran”. Yale Global Online, July 7, 2016. https://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/china-pivots-middle-east-and-iran.

Hayoun, Massound, 2016. “China’s Approach to the Middle East Looks Familiar”. The Diplomat, November 29. https://thediplomat.com/2016/11/chinas-approach-to-the-middle-east-looks-familiar/.

Irish, John. 2016. “China Rules out Joining Anti-Terrorism Coalitions, Says Helping Iraq”. Reuters, February 12, 2016. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-china/china-rules-out-joining-anti-terrorism-coalitions-says-helping-iraq-idUSKCN0VL1SV.

Jin, Wang. 2016. “China and Saudi Arabia: A New Alliance?”. The Diplomat, September 2, 2016. https://thediplomat.com/2016/09/china-and-saudi-arabia-a-new-alliance/.

Liao, Janet Xuanli. 2013. “China’s Energy Diplomacy and its peaceful rise ambition: the case of Sudan and Iran”. Asian Journal of Peacebuidling, Vol. 1, No. 2, 197–225.

Luft, Gal. “China’s Grand Strategy for the Middle East”. Foreign Policy, 26 January 2016. http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/01/26/chinas-new-middle-east-grand-strategy-iran-saudi-arabia-oil-xi-jinping/.

Ma, Xiaolin. 2010. “Chinese Media Coverage of the Middle East over the Past 60 Years.” Arab World Studies. No. 2. 49–60. http://www.mesi.shisu.edu.cn/_upload/article/d1/8f/cd08a3cf44bcacf6e08bd5efa50b/05267127-4d1b-4bce-899f-28ec91cc2169.pdf.

Marcus, Jonathan. “The ‘globalisation’ of China’s military power”. BBC, February 13, 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-43036302.

N.D.. 2017. Xin Jinping on Governance (Volume 2). Beijing: Foreign Language Publishing House.

Olimat, Muhamad. 2013. China and the Middle East: From Silk Road to Arab Spring. New York: Routledge.

Olimat, Muhamad S. 2014. China and the Middle East since World War II. New York: Rowman & Littlefied-Lexignton.

Pan, Guang. 1997. “China’s Success in the Middle East”, Middle East Quarterly, December: 35–40. https://www.meforum.org/articles/other/china-s-success-in-the-middle-east

Perlez, Jane, “President Xi Jinping of China Is All Business in Middle East Visit”. The New York Times, January 30, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/31/world/asia/xi-jinping-visits-saudi-iran.html.

Romaniuk, Scott M. and Tobias J. Burgers. 2016. “China’s ‘Arab Pivot’ Signals the End of Non-Interference: China’s Interests in the Middle East may Lead Beijing to Assure a Military Role in the Affair of Arab States.” The Diplomat, December 20, 2016. https://thediplomat.com/2016/12/chinas-arab-pivot-signals-the-end-of-non-intervention/.

Scobell, Andrew and Alirera Nader. 2016. China in the Middle East. New York: Rand Corporation

Sharma, Bal Krishan and Nivedita Das Kundu. eds. 2016. China’s One Belt One Road: Intiative, Challenges, and Prospects. New Delhi: Vij Books India Pvt Ltd.

Shicor, Yizhak. 1979. The Middle East in China’s Foreign Policy, 1947–1977. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Simpfenforfer, Ben. 2009. The New Silk Road: How A Rising Arab World is Turning away from the West and Rediscovering China. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Su, Alice. 2016. “‘Let’s not Talk Politics’: China Builds Middle East Ties Through Business”. Al-Jazeera America, 20 February 2016. http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2016/2/20/china-middle-east-business-politics.html

Vice, Margaret. “In global popularity contest, US and China – not Russia – vie for first”. Pew Research Center, August 23, 2017. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/08/23/in-global-popularity-contest-u-s-and-china-not-russia-vie-for-first/.

Wagner, Daniel and Giorgio Cafiero. “Is the US Losing Saudi Arabia to China?”. Huffington Post, January 23, 2014. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/daniel-wagner/is-the-us-losing-saudi-ar_b_4176729.html

Xu, Qinduo. “Xi Jinping in the Middle East, Treading New Ground”. Xinhuanet, January 24, 2016. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2016-01/20/c_135028537.htm

“Arab Policy Paper”. Xinhua, 13 January 2016. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2016-01/13/c_135006619.htm

“Backgrounder: China-Arab States Cooperation Forum”. Xinhuanet. May 12, 2016. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-05/12/c_135354230.htm.

“China Holds First Anti-Terror drills with Saudi Arabia”. Reuters, October 27, 2016. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-saudi-security-idUSKCN12R0FD.

“China to host Palestine-Israel peace symposium”. Xinhuanet, December 15, 2017. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-12/15/c_136829097.htm.

“China, Jerusalem and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict”. Middle East Institute, February 20, 2018. http://www.mei.edu/content/map/china-jerusalem-and-israeli-palestinian-conflict.

“China Seeks Support for Israel-Palestinian Peace Plan,” South China Morning Post, August 1, 2017. http://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/2104968/china-seeks-support-israel-palestinian-peace-plan.

“China Issues Arab Policy Paper”. State Council, The People’s Republic of China, January 13, 2016. http://english.gov.cn/news/international_exchanges/2016/01/13/content_281475271410542.htm

“China Surpassed the United States as the World’s Largest Crude Oil Importer in 2017”. EIA, February 5, 2018. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=34812.

“China and Iran Carry out Naval Exercise near Strait of Hormuz as US Holds Drill with Qatar”. South China Morning Post, June 19, 2017. http://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy-defence/article/2098898/china-and-iran-carry-out-naval-exercise-near-strait.

Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hong Lei’s Remarks on the UN Security Council’s Vote on the Draft Resolution to Refer the Situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court. Ministry of Foreign Affairs (FMPRC), May 23, 2014. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/2535_665405/t1158923.shtml.

“News Analysis: Belt & Road Initiative shores up China-Mideast cooperation”. Xinhuanet, January 23, 2016. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-01/23/c_135038752.htm.

“Palestine-Israel Peace Symposium: Two State Solution only Viable Option”. Xinhuanet, December 23, 2017. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-12/23/c_136846269.htm.

“Special Envoy of the Chinese Government on Syrian Issue Xie Xiaoyan Attends Geneva Peace Talks on Syrian Issue”. Foreign Ministry of the People’s Republic of China (FMPRC), March 28, 2017. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/zzjg_663340/xybfs_663590/xwlb_663592/t1450517.shtml.

“Special Envoy of the Chinese Government on Syrian Issue Xie Xiaoyan Visits Syria”. FMPRC, June 18, 2017. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/zzjg_663340/xybfs_663590/xwlb_663592/t1472117.shtml.

“Special Envoy of the Chinese Government on Syrian Issue Xie Xiaoyan Visits Egypt”. FMPRC, April 24, 2017. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/zzjg_663340/xybfs_663590/xwlb_663592/t1457302.shtml.

“The Great Well of China, Economists”. The Economist, June 20, 2015. https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2015/06/18/the-great-well-of-china.

“China’s Xi says to prioritize energy cooperation with Iran”, Reuters, September 29, 2015. https://ca.reuters.com/article/topNews/idCAKCN0RT0B920150929.

“China, Iraq sign memo to promote energy partnership”. State Council of the People’s Republic of China, December 23, 2015. http://english.gov.cn/premier/news/2015/12/23/content_281475259135066.htm.

“New Analysis: Belt and Road Initiative Shores up China-Mideast Cooperation”. Xinhuanet, January 23, 2016. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-01/23/c_135038752.htm.

“Work Together for a Bright Future of China-Arab Relations” (Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Speech at the Arab League Headquarter). January 21, 2016. http://english.cri.cn/12394/2016/01/22/4182s914033.htm.

“The Middle East’s Pivot to Asia”. Foreign Policy, April 24, 2015. http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/04/24/the-middle-easts-pivot-to-asia-china/.

“Xi’s Fruitful Middle East Tour Highlights China’s Commitment to Building New Type of Int’l Relations”. Xinhuanet, January 24, 2016. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-01/24/c_135040319.htm.

“President Xi Jinping Visits Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iran”. Xinhuanet. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/cnleaders/201601xjp/index.htm.

“China’s Xi Calls for Greater Counter-Terrorism Cooperation with Turkey”. Reuters, May 13, 2017. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-silkroad-turkey/chinas-xi-calls-for-greater-counter-terrorism-cooperation-with-turkey-idUSKBN18A01D.

“ Dont Expect ‘Quick Fix’ in Syria, China Tells EU”. EUObserver, April 26, 2017. https://euobserver.com/foreign/137680.

“China Adopts First Counter-Terrorism Law in History”. Xinhuanet, December 27, 2015.http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2015-12/27/c_134956054.htm.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Influence of China in Bringing Peace to Myanmar

- Opinion – Beijing’s Position on the Myanmar Coup

- Opinion – China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Pragmatism over Morals?

- Opinion – The Impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative on Central Asia and the South Caucasus

- Opinion – The Risks of China’s Growing Influence in the Middle East

- The Role of the Maldives in the Indo-Pacific Security Space in South Asia