Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF) – also commonly referred to in Arabic as the Hashd al-Shaabi or in English as the Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) – comprise a diverse range of paramilitary groups that are constantly evolving as they seek to gain legitimacy and political and economic influence. A generally accepted estimate is that the PMF comprises 50 armed groups and around 150,000 fighters. These groups range in size from one thousand fighters or less, to as many as twenty thousand. The largest and most powerful PMF groups are led by influential figures who can be conceptualised as hybrid actors; that is, political actors who make claims to legitimacy on the basis of either state or non-state sources of authority, and create ambiguity by shifting between the two at different times or for different purposes. Having achieved a legal status that allows them to operate as a semi-autonomous, parallel security force, the PMF groups are now establishing themselves as influential political and economic actors, and this will have impacts for state and society in Iraq.

Defining the PMF

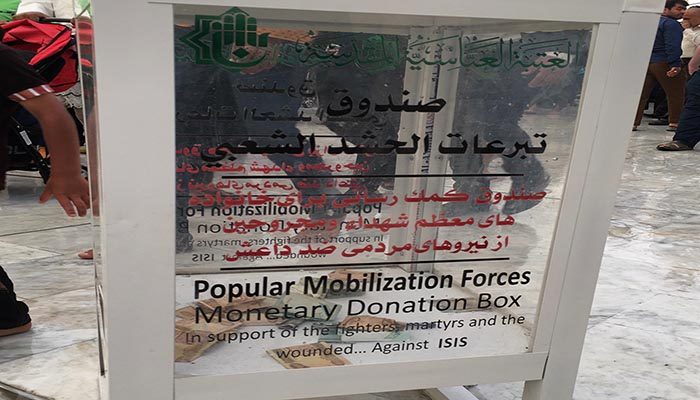

The conventional narrative of the PMF, common in the international media and in some policy and academic analysis, is that it was formed in response to the rapid emergence of Daesh, the so-called “Islamic State” terrorist group. The territorial expansion of Daesh prompted influential Shi’a religious leader, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, to urge pious Iraqis to volunteer to protect religious sites and communities across the country. The Grand Ayatollah’s 2014 statement came at a time when Daesh was making lightning territorial advances with an eye on capturing the capital, Baghdad, and the Iraqi security forces were proving incapable of countering the threat. Thousands of young Iraqis responded to the call and the PMF was formed as a network of paramilitaries fighting in a more or less coordinated manner. It went on to play a role in every major battle against Daesh in the years that followed.

It should be stressed, however, that a number of political actors and already well-established paramilitary groups capitalised on the Grand Ayatollah’s statement to recruit young people to their ranks, manufacture a degree of religious and moral legitimacy, and justify the deployment of their forces in various parts of the country. Not all PMF groups, therefore, were established in response to the threat of Daesh. Some date to the post-2003 period of insurgency and civil war following the US-led invasion and occupation of Iraq, established for the purpose of resisting occupation or protecting specific communities from predatory criminal violence. Others have an even longer history, having been formed during the long years of the Ba’ath regime.

While it is certainly true that the majority of the paramilitary groups that comprise the PMF can be described as Shi’a Muslim, in terms of either their stated religious and political aims or the predominant faith of their leaders and personnel, it is important to note that not all groups are Shi’a and that the Shi’a groups are not unified. Indeed, the Shi’a groups are frequently in disagreement, particularly when contesting for political or economic influence; this also leads, as shall be discussed below, to the continual formation and dissolution of alliances and the fragmentation of groups into smaller groups. The non-Shi’a groups within the PMF represent other religious or ethnic groups and tend to have the characteristics of a local self-defence force.

There is a tendency for international observers to view the PMF through the lens of Iranian regional influence and great power rivalry in the Middle East; the PMF groups are often characterised as “Iran-backed militias” or even “Iranian proxies”, and for some political actors and paramilitary units within the broad PMF grouping this is true to an extent. Some profess ideological commitment to the Iranian religious and political leadership, or have historical connections to political actors in Iran who provided financial or other support during periods of armed resistance to either the Ba’ath regime or the US occupation. Yet a common position on foreign influence in Iraq – including both Iranian and US – has recently emerged, perhaps in response to broader nationalist sentiment across Iraqi society, prompting PMF leaders to distance themselves from perceived loyalty to Iranian interests. The relationship between PMF leaders and their purported Iranian patrons is therefore subject to change and negotiation; the term “proxy” can at times be misleading and overly simplistic.

How the PMF is evolving

As they seek legitimacy, and the political and economic influence that it allows them to access, the PMF groups are evolving in three main ways: as a network of paramilitary groups, as a hybrid political class with growing access to the institutions of the state, and as a (legal and illegal) economic force in diverse sectors of society.

On the battlefield, the PMF groups have progressed through several developmental stages. Initially the religious and political mandate for their paramilitary activities allowed for the protection of holy sites such as shrine cities and mosques. Such sites were deliberately targeted by Daesh to create religious divisions and foment civil war along religious lines, just as they had been by Daesh’s forerunner, al-Qaeda in Iraq. PMF activities soon expanded to include frontline fighting against Daesh, alongside the Iraqi security forces, to halt and eventually roll-back the terrorist group’s territorial project. While the US was officially opposed to non-government paramilitary groups in Iraq, its forces cooperated with PMF groups during the war against Daesh. In areas liberated from Daesh occupation, some PMF groups now function as a “de facto national guard” that provides local security where the Iraqi security forces lack the resources to do so.

This shift in the scope of PMF activities has been accompanied by a growth in institutional power, which began with legitimising narratives about the role of PMF paramilitaries in protecting sacred sites and local communities as a national or religious duty. Next, the PMF achieved legal recognition in November 2016 with the passage of the “Law of Command of Hashd al-Shaabi and other Armed Groups”. Critically, the law recognised the PMF as an independent entity under the authority of the Prime Minister (the commander in chief), in parallel to, rather than subservient to, the security forces. In early 2019, PMF fighters were awarded salary and conditions on par with those of the Iraqi security forces.

When the defeat of Daesh was announced in December 2017, PMF groups enjoyed widespread popularity for their role in the fight against the terrorist group and their ability to step up when the Iraqi security forces were unable. At that time, some PMF leaders had already announced an intention to enter politics and there were concerns about the future role of certain PMF groups, particularly those of an overtly theocratic orientation, those considered proxies for Iranian political actors, and those accused of human rights violations during the war against Daesh. The following year prominent PMF leaders, having built their legitimacy and public profile on the battlefield, entered formal politics by establishing parties, forming electoral alliances, and participating in Iraq’s 12 May 2018 parliamentary election. Their Fatah Alliance secured the second largest number of votes, enabling it to play an influential role in the new government.

This new segment of the political elite is now competing and collaborating with other political actors. These include the Dawa Party, which until last year’s election had dominated Iraq’s post-2003 parliament, and the parties associated with influential religious figures such as Muqtada al-Sadr and Ammar al-Hakim. Reflecting its internal diversity, the emerging PMF political class is displaying the same tendency to fragmentation that is evident across Iraqi politics. In a contest for legitimacy and access to scarce resources, PMF leaders are now competing against each other and using “raids and purges” to remove internal threats and consolidate authority. The parliamentary presence of PMF leaders also allows access to the institutions of the Iraqi state, which since 2003 have been a mechanism for political parties to sustain patronage networks and control resources.

PMF groups are likewise establishing themselves as an economic power, both by leveraging their growing influence over certain institutions of the state to participate in post-war reconstruction work and deliver social services, and through illegal business enterprises. The ability of PMF groups to deliver social services has the potential to develop into a compelling legitimising narrative, particularly while many Iraqis remain sceptical of the government’s capacity to do so. There are, however, numerous examples of PMF activities that undermine its image as a social service provider. Recent reporting has highlighted the domination of regional post-war economies by some PMF paramilitary groups for the purpose of generating income from the territories in which they operate and ostensibly provide security. The behaviour of PMF groups that operate security checkpoints has been described as “mafia-like”. Some have gone so far as to accuse PMF groups of engaging in racketeering – that is, “violent involvement in ordinary business activities in order to raise money” – and effectively creating “feudal kingdoms” beyond the control of the legal system and the Iraqi security forces.

Impacts for Iraqi state and society

The evolution of the PMF from battlefield to parliament will have deep impacts on state and society in Iraq for the foreseeable future. While the relationship between political actors and paramilitary groups is not unique in Iraq’s modern history, the plurality of hybrid actors with the ability to command violent action creates an ongoing risk of political competition escalating into armed confrontation. The fragmentation and internal divisions of the PMF exacerbate this risk, although large-scale violent conflict is not in any party’s interest. This risk is also present in the territories liberated from Daesh where PMF groups may clash – with each other or with other armed groups – over access to, and control of, economic resources. There remains a need for PMF groups to be integrated into the Iraqi security forces over time, but the presence of PMF leaders in parliament will stall this process.

PMF leaders, in common with other Iraqi politicians, have expressed their opposition to the ongoing presence of US troops in the country. Indeed, the US government has stated that it believes PMF groups were responsible for two attacks against US facilities in Iraq during September 2018, while in February 2019 the PMF claimed (and the US denied) that its personnel had forcibly prevented US troops from conducting a planned operation in Mosul. There remains a risk that ongoing US military presence in Iraq, particularly as part of a wider action in relation to Iran, may be targeted by PMF paramilitary groups, although no PMF leaders would have an interest in allowing such action to escalate significantly.

Finally, PMF parliamentarians are positioned to influence the decisions of the Iraqi government, including the appointment of officials to government ministries. This provides opportunities for this new, hybrid segment of the political elite, which exercises elements of both state and non-state authority, to “capture” state institutions and embed patronage networks. In practical terms, this allows PMF leaders to leverage state resources to benefit their supporters, paramilitary personnel, and expanding business interests. At a higher level, it is yet another setback in Iraq’s ongoing struggle against corruption.

The quest for political legitimacy has seen the PMF evolve from a volunteer fighting force ostensibly mobilised for the protection of holy sites targeted by Daesh, to a multi-faceted social, economic, and political force with a firm footing in Iraq’s parliament and a parallel security force that receives government-funded salaries and generates income from expanding business interests. The emergence of this new paramilitary-parliamentary political class has occurred at a time when the Iraqi state – including, critically, its security forces – are still contending with deep-rooted problems of corruption, institutional weakness, and low levels of public trust. The PMF, having stepped forward when the Iraqi state faced a seemingly insurmountable challenge, has now become yet one more challenge to the slow process of building a stable and effective state capable of meeting the needs of its citizens.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Iraq’s Toughest Challenge: Controlling the Iranian-backed Militias

- Opinion – Political Challenges Ahead for the New Iraqi Prime Minister

- Water Scarcity and Environmental Peacebuilding: A Lens on Southern Iraq

- International Relations Theory and the ‘Islamic State’

- The PNAC (1997–2006) and the Post-Cold War ‘Neoconservative Moment’

- Huntington vs. Mearsheimer vs. Fukuyama: Which Post-Cold War Thesis is Most Accurate?