Before the economic, political and social crises in Venezuela began in 2013 under the administration of Nicolás Maduro, China had established a strategic partnership with the former President Hugo Chávez in 2001. The strategic partnership was later upgraded and became a comprehensive strategic partnership in 2014 [1]. This approach strengthens the integration and interdependence between both countries. Despite not having a Free Trade Agreement, currently China is the second trade partner of Venezuela, after the United States (U.S.), which favours China’s strategic interests (see Table 1). However, the arrival of Maduro to power has contributed to diminishing in some measure the Chinese economic-commercial presence by recurring tensions, due to chronic internal economic, political and social problems. An example is what took place on January 24th, 2019 regarding the self-proclamation of Juan Guaidó as President of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and the risks of armed conflicts and economic-financial sanctions imposed by the U.S.

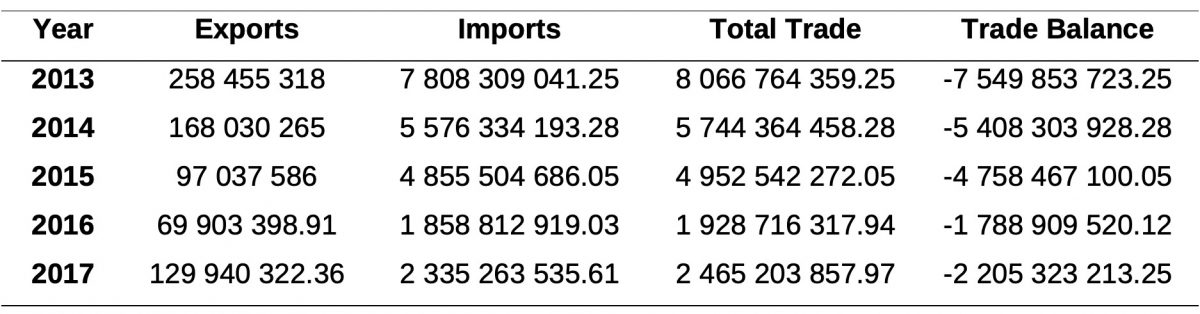

Table 1. Exports, imports and trade balance of Venezuela with China during the government of President Nicolás Maduro, 2013-2017 (In billions of US Dollars). Source: Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Venezuela [2]

Under this context, China has become one of the main investors and lenders of Venezuela and of several Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) states. According to Margaret Myers and Kevin Gallagher in their “China-Latin America Finance Database” report, between 2005 and 2018 China lent more than 627.000 billion dollars to Venezuela, representing 47 percent of total Chinese policy bank finance to LAC, for the most part of China Development Bank and China Eximbank. Likewise, China is a prospective member of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) since 2017. It is also important to emphasise the sign of the Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation within the framework of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative between Venezuela and China in 2018. China has an active role in infrastructure investment and over the development of large transport and energy projects within Venezuelan territory.

According to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela is the main Latin American country that has assigned the largest resources to these types of contracts with the Chinese companies with a percentage of 38.3, followed by 15.4 percent from 2000 to 2015. Current and future investments in infrastructure and other Chinese economic projects are likely to be under the Belt and Road Initiative. However, Chinese President Xi Jinping has maintained a cautious foreign policy toward the South American country’s conflict, but has supported President Maduro’s regime against the aggressive and interventionist policy that President Donald Trump has implemented against Maduro´s regime.

Although this attitude could likely be explained from different approaches, this brief article is aimed towards analysing Chinese foreign policy in relation to Venezuela, which the government assures is a policy of non-intervention, but promotes free trade policy, particularly among its strategic partners of the Global South. China seeks to project its image as an international actor with global responsibility, primarily in the Western World. However, China is not interested in the establishment of a democratic regime in Venezuela, neither in the defence of human rights. China does not interfere in the internal affairs of other states and Chinese authorities expect the same reciprocity from others. This article describes the non-intervention policy as a pragmatic and cautious instrument that serves for the achievement of their national interests. The pragmatic position maintains a sense of urgency and provides practical solutions in the process of adaptation in a global context, helping to reinforce the legitimacy of power and permanence of the Chinese Communist Party. This cautious position seeks not to interfere into possible conflicts with other states.

Historically, the non-intervention principle has its origins in the signature of the Tibet Agreement between China and India, signed in 1954. This agreement defined the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence for China and the Five Virtues (Panchsheel in Sanskrit) for India. They are: mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. These principles have led China´s foreign policy at different levels, mostly when it claims rights related to sovereignty and the principle of non-intervention in its internal affairs.

The spread of Covid-19 has deteriorated the bilateral relations of China with the U.S., and it has escalated into an economic-commercial, technological and scientific conflict. The Chinese government has had a prominent presence in LAC, particularly in Venezuela, while the U.S. presence in the region is weaker. In May, during the 73rd session of the World Health Assembly, President Xi Jinping declared that “when the Covid-19 vaccine is development and available in China, it would be granted as a global public good”. By July 20th, the Venezuelan government reported the lowest number of Covid-19 confirmed cases in the region, with about 12334 people infected and 116 confirmed deaths.

The Chinese government has tried to take advantage of the pandemic to increase its power and improve its position as a global leader. A good example concerns Chinese opportunism within fragile states such as Venezuela. China has shipped at least one million rapid coronavirus tests, 150.000 molecular diagnostic kits, and approximately 8 million face masks. Besides, the government has distributed nearly two million disposable gloves, up to 135.000 protective suits, more than 23.000 infrared thermometers, and 14.000 lens protectors – a total of 46 tons of medical supplies imported since March 19. On June 6th, a new Chinese cargo plane arrived in Venezuela, carrying 70 tons of medical equipment.

Due to the fragile situation in Venezuela and the intensification of tensions with the U.S., the Maduro government needs to recognise China’s humanitarian assistance, which might have serious repercussions on its sovereignty and autonomy. Furthermore, there is a risk that Venezuela might be the recipient of Chinese unilateral imposition. In the context of this asymmetrical relationship, Sino-Venezuelan cooperation has been ineffective in finding solutions to old crises. China´s presence in Venezuela is not the best option to diminish the social crisis, but it is an option to maintain the current Venezuelan government. Moreover, Venezuela has been subject to a double dependence with China and with the U.S. In the medium term, the Venezuelan government´s narrative would be to present itself as a victim of the hegemonic powers, legitimating its aggressive action against its population.

Nevertheless, Venezuela is facing other severe domestic challenges despite the Covid-19 pandemic. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) revealed that undernourishment has increased fourfold, from 6.4 percent in 2012-2014 to 21.2 percent in 2016-2018, which pushed at least 6.8 million Venezuelans to starvation. Likewise, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), between 2016 and November 2019, the crises have caused the massive exodus of migrants from Venezuela. It is estimated that about 4.6 million men, women, and children have left the country. A low-level infection of the Covid-19 virus coincides with an increase in migration, and a reduction in the Venezuelan population. Nonetheless, facing the breakdown of multilateralism or global collective leadership, Venezuela and China have not yet expressed their willingness to work in a coordinated manner to fight against the social subsidence. Even though China stresses its position: “In difficult times China and Venezuela are always together”, as the current Chinese ambassador to Venezuela, Li Baorong stated.

A national economic deterioration including the drop in GDP of around 70.1 percent between 2013 and 2019, and the external debt which exceeds 157.000 billion dollars in 2018, and its international reserves, fell by around 832 million in January 2020 – generating important challenges for the Maduro government to overcome. These factors have contributed to deepening poverty and social marginalisation, as a result the homicide rates are rising [3], the organised criminal groups are increasing, alongside unemployment [4], malnutrition, fuel shortages, a lack of basic drinking water access, power outages and public health deterioration, among other challenges.

Likewise, the deterioration in the health care system and the lack of medical personnel make it difficult to contain COVID-19, due to the fear among Venezuelans of being treated in unsanitary conditions. Another external challenge regards diplomatic recognition and support of almost 60 countries to Juan Guaidó, and the adoption of coercive measures against the Maduro government. On July 2nd 2020, the English High Court recognised Juan Guaidó as the “constitutional interim president”, granting him the control of $1 billion of its gold stored in the Bank of England. According to the Maduro government, the 31 tons of gold would be used to confront the pandemic in Venezuela. Juan Guaidó’s recognition by Britain as Venezuela’s legitimate and legal president, as well as the support from other states, has contributed the administering of these funds by the interim government.

China´s diplomatic position

It is accurate that the Chinese government has changed its position toward the situation in Venezuela to abide by the basic principles of international law and to oppose foreign and military intervention in Venezuela. Likewise, China also refuses to use humanitarian aid for political purposes to create instability in the Bolivarian country. However, there is some intentional ambiguity between discourse and facts, it has only been pronounced that the Venezuelan government and the opposition seek “a political solution through dialogue and consultations” but without directly intervening or actively participating in the conflict. On one hand, China rejects the integration of the Montevideo Group proposed by Mexico and Uruguay that is aimed towards avoiding the intervention of the U.S. in the Lima Group, yet on the other hand, openly criticises Western interference in the form of “humanitarian aid”. By taking a stand in favour of Maduro, China would barely have the intention and credibility to negotiate with the Venezuelan opposition.

Amid the Covid-19 pandemic, in the state daily newspaper People’s Daily, China criticised the U.S. for the lack of global commitment to the fight against the new and unexpected virus:

Besides, the U.S. sanctions against Iran, Cuba and Venezuela seriously damaged these countries’ efforts to fight the pandemic. Is the U.S. still calling itself the guardian of global human rights?

Meanwhile, Chinese diplomats call fiercely worldwide for the end of virus-related stigma toward China, called “the China Virus”, “the Chinese Virus”, “the Wuhan Virus” and “the Wuhan Flu”. In Venezuela, the Chinese Embassy condemned the attacks against the Asian nation made by some Venezuelan opposition deputies: “We suggest that some people also take the political virus seriously”.

Two questions arise concerning the Chinese position on non-intervention: What will political-diplomatic cost be to maintain a low profile in the Venezuelan crisis? What are the limits of the China´s non-intervention policy? New concepts have emerged among Chinese academics so that China assumes a major responsibility in global conflicts, concepts such as “creative involvement” in 2011 by Professor Wang Yizhou, Vice Dean of the School of International Studies at Peking University; “constructive participation” in 2011 by Professor Zhao Huasheng of Fudan University [5] and “cooperative engagement”. [6] Although in this case, China has shown a strict adherence to the principle of non-intervention, given the geopolitical circumstances of Venezuela, it is proposed that China seeks a “co-responsible participation”, namely, a shared responsibility with others global players or actors to find a peaceful solution to the humanitarian crisis in Venezuela and other countries in conflict, while China is increasingly engaged in global peace processes: moving from being a peacekeeper to an active peacemaker, as it did during the Civil War in South Sudan. Even so, the defence of peace is also a fundamental and obligatory principle of Chinese foreign policy, adopted in the Constitution of China of 1982. Although China is not responsible for the crisis in Venezuela, it is responsible for continually supporting Maduro’s government, unable to guarantee national and regional stability.

China’s involvement in the Venezuelan crisis will depend on the threat of their interests in the conflict zone, after all, China responds to geopolitical interests. Although the answer is still unclear, currently the Chinese government is not interested in involving itself in an armed conflict. In Venezuela, China has tried to remain prudent and distinct from Maduro’s government, despite being its main economical and political supporter.

Is China intervening in Venezuela?

It depends on the interpretation of the concept of non-intervention. If intervention is understood as the support for the Maduro government to attack the opposition, to and decide what type of political and economic regime Venezuela should implement, then, there is no Chinese intervention. Nevertheless, there are indicators that demonstrate the intervention and influence of China.First, there is an oil-lending policy that has helped the Venezuelan political elite to remain in power. Although Venezuelan oil exports have dropped in 2019 due to the U.S. sanctions that deprived Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA), China continued importing Venezuelan crude oil, and has displaced its primary American market. The damage caused by the economic sanctions have represented a severe blow to the state-owned companies, for example, China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC) and its units halted the loading of Venezuelan crude in the second half of 2019. In the same year, Venezuela sent an average of 319.507 barrels per day to China.

Second, Russia and China use their veto power because they consider that coercive measures and military force should not be used to isolate and attack Maduro´s Venezuela. Until April 2019, four plenary sessions of the UN Security Council were held to address the Venezuelan crisis.

Third, China´s arms sales to Venezuela empowers the Maduro government to commit violations or human rights abuses against the opposition and the Venezuelan population. For SIPRI, the Venezuelan military spending has been drastically reduced, and Venezuelan arms imports fell by 83 percent between 2009–13 and 2014–18. According to the Venezuelan non-governmental organization Control Ciudadano: “Since 2013, China has had the largest military equipment contracts with Venezuela. In that year, Beijing signed a contract for the sale of weapons systems, and in 2014 acquired another ten weapons systems”. Although the economic crisis has forced to reduce the arms acquisition, in 2016 Venezuela´s arms purchases from China increased once again. Due to Venezuela’s secrecy regarding these purchases, it is difficult to estimate the influence China has had on military and technological cooperation with Venezuela.

Fourth, in 2013, China’s acceptance of the credentials of the Venezuelan ambassador, Iván Zerpa Guerrero, is a way of influence over Venezuelan internal affairs. An explicit recognition of the current Venezuelan government until today.

Fifth, the effort to straighten and reinforce the Sino-Venezuelan cooperation or Chinese aid on health matters is another probe of support of the Maduro regime from Beijing in order to continue safeguarding its strategic position in LAC.

However, it is legitimate for China to continue recognizing the Maduro government, a government that arrived democratically in 2013 and with which China has established strategic diplomatic relations. In addition, it is also legitimate for China to protect its interests, despite sometimes contradicting the principle of non-intervention. Therefore, although its traditional principle of non-intervention continuously regulates its international actions, sometimes the interpretation of this principle is rigid and flexible. China´s non-intervention policy in the non-questioning of the Maduro government has prevailed, however, this traditional principle of foreign policy has been relaxed at certain times. For example, China has sought the International Contact Groups and the Venezuelan opposition led by Juan Guaidó to find a political solution, this does not mean a Chinese direct intervention.

Financial support for oil and gas extraction is unfavourable for fragile states such as the South American country, but it is important for ascendant powers such as China, especially for being rich in these strategic natural resources. This is an asymmetric game of international power, but empowers the Maduro regime’s political elite, and it helps to expand Chinese interests and to increase its influence in Venezuela and LAC. Besides this, dependence would likely be reinforced as a result of the pandemic.

China has tried to be “careful” by not interfering in an open manner as traditional powers, European and American, have done in the internal affairs of weak states. To some extent, China is covertly doing this due to Venezuela’s degree of vulnerability and dependence. Thus, China´s non-intervention policy could be understood more as a geopolitical instrument than as an end in itself. In sum, the orientation of China’s foreign policy based on the principles of peaceful coexistence could contribute to pacify the Venezuelan situation, taking distance from the interventionist policy of the U.S., to take advantage of the benefits offered by the Sino-Venezuelan strategic partnership and its long-term relationship with LAC.

Final thoughts

China’s presence and influence in Venezuela in times of crisis forces deeper reflection on its place in the world and its acquisition of responsibilities as a consequence of its rising global relevance. In this sense, it is important to ask: How China’s non-intervention principle could be adapted to the new global conflicts?

Due to the decline of multilateralism, China’s diplomatic activism during Covid-19 has had a greater global projection and it has reinforced its leadership at geographically distant zones. The weak responsiveness of the Latin American governments to face new challenges and old structural problems has been evidenced and exacerbated due to the virus. It has also allowed a new opportunity for China to rethink its agenda for cooperation on issues related to the Covid-19 pandemic, such as medical supplies, collaboration to develop a coronavirus vaccine, exchange of information, and results in the adoption of public policies to mitigate and prevent the spread of the new virus. It is important to mention that China unilaterally has not imposed its political preferences and moral values.

China has positioned itself in Venezuela and it has halted a foreign policy that is active and cautious in the face a relative power vacuum left by the U.S. China´s influence in Venezuela has caused geopolitical clashes between China and the U.S. Moreover, Latin America is the U.S.’s traditional zone of influence and the American government, regardless of their political ideology, seek to contain Chinese expansion. Meanwhile, China has taken a leading role in favour of globalisation, and it has adopted a collaborative position in the structure of the liberal international system and China has backed its institutions such as the World Health Organization (WHO). One of the biggest challenges to China´s diplomacy in Venezuela is the demand for protection of the basic rights guaranteed to the people of Venezuela under the international law, China should avoid regionalization of conflict and strengthen regional multilateralism to support Venezuela out of the crisis. This is undoubtedly an opportune time for China to be congruent with its foreign policy principles and objectives in the context of the transition process of the global power centre displacement from the U.S. to China.

Notes

[1] At the bilateral level, China establishes partnerships with its foreign counterparts and establishes a cooperation agenda in multiple areas. Each association is different in the degree of geopolitical importance. There are four types of partnerships -from minor to major degree of importance-: comprehensive cooperation, strategic, comprehensive strategic and global strategic. Nonetheless, the foreign partner must fulfill the following conditions to create strategic partnership with China: to recognize China’s position that Taiwan is an inalienable part of the territory of the People’s Republic of China and not intervene in Chinese internal affairs.

[2] There is little official information concerning the bilateral trade and the database is not up to date.

[3] According to the Global Study on Homicide 2019 of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, there are 56.8 intentional homicides per 100.000 population.

[4] According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), unemployment will rise by about 44.3 percent in 2019; the coronavirus can deepen unemployment by nearly 47.9 percent in 2020.

[5] Chen, Z. (2016) “China Debates the Non-Interference Principle,” The Chinese Journal of International Politics, Vol. 9, No.3, 357.

[6] Yizhou, W. (2017) Creative Involvement: The Evolution of China’s Global Role. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis, 47.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – The Survival of Venezuela’s Bolivarian Revolution

- Disputing Venezuela’s Disputes

- Venezuela: A Difficult Puzzle to Solve

- Opinion – Venezuela’s Migrants and the Challenges of Trinidad and Tobago

- UK-China Film Exchange: Cultural Relations in a Competitive Age

- Regional Responses to Venezuela’s Mass Population Displacement