Securitisation is the process by which something is transformed into a real or imagined security threat, needing an urgent policy response. The securitisation of migration (the movement of people across borders for a multitude of different reasons) has been a topic of academic debate and political discussion in recent years. The migrant category of asylum-seeker is worth examining separately in the securitisation debate, due to the specific set of challenges that migrants seeking protection pose, or are framed as posing, to the nation state.

According to the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951) and 1967 Protocol, an individual can be recognised under international law as a refugee when they establish a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country, based on race, nationality, religion or membership of a particular social group (Adamson, 2006). These individuals qualify for the protection of another state and there is a specific set of rules under international refugee law that dictate their rights. According to Gibney (2014), there is an important distinction between the term refugee and asylum-seeker. He outlines two distinct groups of migrants that fit neatly into the definition of refugees: those that need help in fleeing to a safe country because of danger in their own country and those awaiting resettlement in a refugee camp. However, asylum-seekers are those that arrive at a national border claiming to need protection (Gibney, 2014). The important distinction here is that by this conceptualisation, refugees have already been defined as eligible for protection by the receiving state before they arrive in the country. Gibney (2014) puts forth an interesting argument, that although the claim for protection from persecution is the same for both refugees and asylum-seekers, asylum-seekers raise unique moral and practical issues. The politics around asylum-seekers are dominated by the fear that individuals are exploiting the asylum system by falsely claiming to be a refugee, because “to be an asylum-seeker an individual merely has to claim to be a refugee” (Gibney, 2014, p. 10).

For the purpose of this analysis, asylum-seekers are individuals or groups of people that are claiming asylum based on persecution but have not (yet) been granted refugee protection by the host country. Therefore, they are considered to have arrived, or intend to arrive, in a country with the intent to, or are in the process of, claiming asylum. This definition is important in order to understand the real or imagined threat to national security these individuals pose to the host country. Is their so-called threat status heightened because they arrived without pre-established permission, or refugee status? Does this liminal state, of claiming asylum but not yet having been granted it, make them an easier target for politicians who can leverage slow and expensive asylum procedures for political gain? Given these questions, how have asylum-seekers come to be framed, and perceived, as a threat to national security, particularly in the two historically migrant-rich, yet currently anti-migrant, countries of Australia and the United States?

The comparison between Australia and the United States of America, in relation to asylum-seekers, is interesting for a multitude of reasons. Firstly, both nations have a history of mass former immigration. Both the US and Australia, as former colonies of Britain, are nations built from ‘settler’ societies, marginalising and causing the death of the majority of the former indigenous inhabitants. Both states relied on immigration to boost population numbers, in colonial Australia (Macintyre, 2009) and in the US (Steckel, 1989) throughout the 1800s. During the Menzies government (1949-1966), politicians and policy makers believed Australia’s security could be increased through a stronger economy and increasing population through immigration (McLean, 2001). This begs the question however of which migrants were accepted and under which conditions, which will be explored later.

Secondly, it appears that both nations have become increasingly anti-immigration throughout the late 20th Century and early 21st Century, with the current Liberal government in Australia under Prime Ministers Tony Abbott (2013-2015), Malcolm Turnbull (2015-2018) and Scott Morrison (2018-current), and with the current Republican presidency of Donald Trump. This also raises questions about how new these policies are, and whether the conservative political rhetoric reflects greater historical forces or the contemporary political climate.

Thirdly, both nations have historically been perceived as a multicultural, immigrant society, as a melting pot of different (mostly European) cultures. McMaster (2002) opens his piece with the following remark: “Australia has the reputation of a tolerant multicultural nation; indeed, a fine example of a successful immigrant society” (p. 279), and then outlines the paradoxical nature of this reputation given the history of racist and controversial policies. The US is also built on immigration and consists of a mix of White, African American, American Indian, Asian, Hispanic/Latino or Middle-Eastern and North African (United States Census Bureau, 2017), but an Anglo-Saxon ideal has dominated ‘Americanisation’ (Schain, 2010). Although both nations are, or have historically, been perceived as a multicultural society, some cultures were “far less welcome as part of the melting pot” and others “excluded from the pot entirely” (Schain, 2010, p. 215-216).

National Security and the ‘Unidentifiable’ Threat

To analyse why asylum-seekers are considered, or framed as, a threat to national security, the concept security must first be defined. As explored by Williams (2007), security is a difficult term to define, and it has no objective meaning. Rather, “(in)security is what people make it” (Williams, 2007, p. 1022), speaking to the subjective and malleable nature of the concept. Williams (2007) continues to describe that most analysts consider security in terms of the alleviation of urgent and necessary threats, both in terms of conditions necessary for survival and to “pursue cherished political and social ambitions” (p. 1022).

Furthermore, the distinction between national and human security is important in the discussion on securitisation. The recent history of security can be split into roughly three phases: Cold War security, post-Cold War security and post-9/11 security. Whilst Cold War security was primarily concerned with the threat of communism militarily and politically, after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 bipolarity in international affairs subsided and security became about threats to global peace.[1] Consequently, a human security agenda persisted in the 1990s concerned with a doctrine of protection and an increase of multi-lateral humanitarian interventions.[2] The concept of human security, born out of the 1994 United Nations Development Report, links the concepts of human rights, development and security through the idea that the individual should have freedom from fear and want (Ogata & Cels, 2003).

Michael Barnett (2011) in Empire of Humanity discussed increasing concerns with events happening abroad and how this could impact security of the individual at home. Barnett asserts that, “[i]n the 1990s, everything changed … Covered by 24-hour news agencies, the world could now watch in real time, the horrific spectacles of state failure, civil war, ethnic cleansing, and genocide”, implying that the changed interaction of the individual with media impacted evolving discourse on security. This perspective supports the idea that 9/11 cannot be regarded as the event that changed the nature of security – that continuity from the 90s exists.

A shift in concern from human to national security can be observed at the turn of the 21st Century. The post-9/11 security conceptualisation is embedded in state-centric concerns about the sovereignty and safety of the nation. In his inaugural address in 2005 George W. Bush, referring to the September 11 attack on the US in 2001, stated that “[w]e have seen our vulnerability … violence will gather, and multiply in destructive power, and cross the most defended border and raise a mortal threat” (“Key Quotes”, 2005). In this sense, weak states were conceptualised as dangerous, creating global insecurity, and state strength redefined as security created through pre-emptive resilience building.[3] Returning now to William’s (2007) definition of security as the alleviation of threat, the shift from human to national security has replaced the emphasis on alleviation of threat to individuals’ human rights with the alleviation of threats to the nation-state.

Securitisation theory has sought to define various aspects of a process that generally occurs, for something to be securitised. Securitisation is transformative – describing how something is turned into a threat to the nation-state. Fisher and Anderson (2015) explore how securitisation occurs as a speech act, usually by western policy makers, where an ‘event or space’ becomes an existential threat. This threat exists in reference to a Western state or population and is used in order to legitimate exceptional responses by political leaders (Fisher and Anderson, 2015). This response is beyond the scope of normal, accepted political behaviour, and thus could defy the norms and laws of a society. This breach is however justified by the imminent threat to the state or its population.

This definition posed by Fisher and Anderson (2015) raises a few issues needing to be explored further. The deliberate use of the word ‘existential’ to define the threat created by securitisation is important as it alludes to a blurring of the lines of real and imaginary. Existential means “implicitly or explicitly asserting actuality as opposed to possibility” (Miriam-Webster, 2018), and given that this threat is created through a speech act, it implies that even if the speech act is claiming a threat based in falsehood, it will create a very real perception of threat. This will be important to come back to given today’s discussion on ‘Fake News’ and how the actuality of the threat is not the most important factor in it being perceived as such.

The second element of this definition that is interesting in the context of asylum-seekers is the idea that an ‘event or space’ is transformed into an existential threat. What does this entail exactly, and does this mean that a person or group of people cannot be turned into an existential threat? Buzan, de Wilde and Waever (1998) discuss how securitisation is the transformation of an actor or issue into a matter of security, thus implying that individuals or groups can be securitised. To further answer this, one can look historically to what other ‘events or spaces’ have been labelled as threats to national security.

After World War Two, the major threat to American national security was labelled as Soviet expansionism and desire to dominate the Eurasian land mass and throughout the world (Leffler, 1984). During the Cold War era, from the perspective of both the United States and Australia, invasion by communism was the clearest threat to national security. Communism could, very clearly and tangibly, be labelled as the enemy of the state. In Australia, the ‘Domino Theory’ vividly dominated foreign policy and politics, which dictated that “communist movements in Asia formed part of a monolithic, inherently expansionist Communist world with headquarters in Moscow and Beijing” (McLean, 2001, p. 316). Australia’s similar labelling of communism as the national enemy has been called a by-product of US domination, and historians have debated on whether there was a real threat from communism (McLean, 2001), or whether this imagined threat was created through securitisation. Regardless, this common perceived threat to national security during the Cold War serves to make Australia and the United States an interesting comparison today.

In the United States, anti-communist bias defined asylum policy throughout the Cold War and asylum was used as a geopolitical tool. Cubans and Indochinese refugees fleeing the communist regime were granted asylum, whereas Haitians were proactively excluded from asylum throughout the 1960s and 70s (Hamlin, 2012). In the 1980s the US Coast Guard began interdiction at sea, to profile the refugees and make sure that only those with strategic political value were allowed in (Hamlin, 2012). Similarly, Australia’s first wave of Asian asylum-seekers arrived from Vietnam, where they were fleeing from communism (McMaster, 2002).

When the Cold War ended the threat of a communist invasion dissipated with it, and the enemy of the state became less clear. In post-Cold War international politics, non-state actors became increasingly important and threats to the state diversified.[4] Threats to national security can range anywhere from drugs, and associated criminal networks (Crick, 2012; Carrapicco, 2014), to public health (Kelle, 2007; Leboeuf & Broughton, 2008; Lo Yuk-ping & Thomas, 2010) and climate change (Broszka, 2009). The fall of the Soviet Union appeared to open-up the possibility for a broader range of phenomena to become associated with a threat to security.

A significant part of securitisation theory is to consider the context in which a current discourse is created, and the history in which it is embedded. Hamlin (2012), in a historical exploration of US asylum policy, explores how policy change can best be understood in terms of long-term processes. Hamlin (2012) argues that throughout the Cold War, changes regarding increases in border security, regimes of deterrence, expedited removal processes and mandatory detention of asylum-seekers were already occurring in the US. Although it appears as if a dramatic change occurred following the September 11 attacks, Hamlin (2012) argues that today’s restrictive measures have a long history. Therefore, the Cold War enabled exceptions for those fleeing communism, but there was underlying continuity in regimes of deterrence of asylum-seekers. The change lies in the fact that politicians became increasingly concerned with border security after 9/11 (Hamlin, 2012), perhaps because of the political capital to be gained.

That brings us to the central question – what is the current political discourse surrounding asylum-seekers and national security? How are asylum-seekers framed by those in power, and how are they consequently perceived by society? In the following section, we are concerned with the different aspects of the threat that asylum-seekers are framed as posing to Australia and the United States.

Elements of the Threat

Threat to National Sovereignty

State sovereignty is central to the discussion of asylum-seekers and national security, as well as a guiding principle in international law. According to liberal interdependence theorists, sovereignty is the “state’s ability to control actors and activities within and across its borders” (Thomson, 1995, p. 213). State sovereignty concerns its national borders and the right of the state to control and regulate who comes and goes from that state. Asylum-seekers, as non-nationals of the state, breach the state’s sovereignty when an unauthorised entrance occurs.

Torpey (1999) has discussed how the invention of the passport was used as a means of monopolising the control over the movement of individuals across borders, and is now an intrinsic part of the developed state and global system. However, as Adamson (2006) points out, in reality states do not have a monopoly over the movement of people, and non-state actors such people smugglers compete with the state. According to Adamson (2006), 30-50% of migrants to Western industrialised countries are so-called irregular migrants. Irregular migrants, sometimes called illegal migrants, are those that enter through illegal channels (Adamson, 2006). This can include those smuggled, trafficked or those that have entered without (adequate) documentation. Asylum-seekers are part of this group but do not make up the entire group, as it can also include economic migrants. When entering through these ‘illegal channels’, asylum-seekers can become conceived as a threat to national sovereignty because they have entered without the state’s authorisation thus breaching its sovereignty.

Hamlin (2012) discussed how the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)is concerned about mixed migration, where migrants with different motives arrive simultaneously to a country. In this situation, asylum-seekers can become conflated with other migrants as there is doubt cast over the motives of asylum-seekers. Doubt exists about whether asylum-seekers are actually in need of protection, and refugee status, or whether they are just seeking better economic fortunes (Hamlin, 2012). Hamlin (2012) warns however that states can choose how they categorise migrants according to their political needs at the time, and thus the categories of asylum-seeker, refugee and economic migrants reflect the political moment.

Whether an asylum-seeker is a ‘legitimate’ refugee is determined by the state-run asylum procedures and guidelines are outlined in international law, which is itself subject to extensive interpretation. The accuracy and subjective nature of asylum decisions has received much scholarly debate[5] and is beyond the scope of this paper, but the rejection of asylum-seekers plays a role in how they are perceived. In the 1990s, there were 6 million asylum applications in industrialised countries but only a small percentage were found to be legitimate (Adamson, 2006). This large rate of rejection of asylum-seekers can be used by some to justify why most asylum-seekers are not genuine refugees and thus represent a threat to national sovereignty. Hamlin (2012) argues that the evidence that the global acceptance rate for refugees has gone down, yet the number of applications rose, assumes both a good inquiry and interview process, as well as that deterrence policies haven’t hindered genuine refugees in applying.

McKenzie and Hasmath (2013) describe how strict asylum policies “aimed to address national anxieties of porous borders” (p. 420) in Australia. This is supported by Burke (2001), who points out that territorial integrity is perceived to be threatened by asylum seekers. This alludes to the idea that the border as a physical barrier should be impenetrable for a nation to maintain territorial integrity. When asylum seekers can make it through ‘holes’ in the borders, this therefore threatens the sovereignty of a nation. Importantly, wealthier countries can ensure that their border become less penetrable – which speaks volumes for the power dynamics of the securitisation of asylum seekers. Developed nations such as the United States and Australia can invest millions to ensure that the sovereignty of the nation-state is maintained over the human security of the individual seeking protection.

This is highlighted further in the idea that refugees, who have been granted asylum, are depicted as more deserving of protection in Australia. Those who arrive by boat were found by McKenzie and Hasmath (2013) to be framed as ‘jumping the queue’ – thus the manner of arrival appears to matter in the level threat posed. Perhaps this is a political statement of national sovereignty, as with asylum seekers the government does not control who enters.

Adamson (2006) sums up the issue of sovereignty well when she states that “the number of false asylum-seekers, combined with the high level of illegal immigration, contributes to the perception that sates are losing sovereign control over their borders” (p. 174). This is linked to a fear of globalisation and a fear that as the movement of goods and products increases transnational, the world will become increasingly borderless (McMaster, 2002).

Threat to Individual Safety

Asylum-seekers are labelled a threat to peace, and more specifically as a threat to an individual’s safety. Terrorism – both as an existential threat to the sovereignty of the nation, as well as to the safety of the individual (Buzan, 1991) – seems to be at the forefront of this discussion. Asylum-seekers, often having originated from countries involved in war or violent extremism, are labelled terrorists, or as bringing with them the violence they are attempting to escape. Seidman-Zager (2010), in a working paper on the securitisation of asylum-seekers in the UK, discusses how the perceived link between asylum-seekers and terrorists has been a recent development, brought on by the events of 9/11 and global war on terror. The asylum system is labelled as a way for individuals intent on committing terrorist attacks to enter a nation (Malloch & Stanley, 2005; Huysmans & Buonfino, 2008). Seidman-Zager (2010) describes how terrorism is perceived to cause fear, pain and violence, but simultaneously impossible to control, predict and understand. Lastly, he finds that because asylum-seekers are portrayed as anonymous, and their identity difficult to identify (Malloch & Stanley, 2005), it is impossible to know how many of them could potentially be terrorists. Thus, the conflation of asylum-seekers with terrorism causes them to be labelled a threat.

Other than a link with terrorism, asylum-seekers have also been labelled a threat to the individuals’ safety because it is vulnerable to exploitation by young men. Buchanan et al. (2003) found that a common stereotype of asylum-seekers was a dangerous male entering the UK to break up communities. Seidman-Zager (2010) explores how this labelling of asylum-seekers as dangerous is racist ‘othering’ of different religions and cultures. Xenophobic fear of others contributes to the homogenisation of the other, in this case as violent terrorists. In the United States border security heightened after 9/11 because America became afraid of terrorism (Adamson, 2006).

Threat to National Identity

Asylum-seekers are labelled as a threat to nation identity and cohesion because as Adamson (2006) put it, migrants may have split political loyalties. Unlike refugees, who are expected to give up their previous nationality or identity even when they receive the protection of the host country, asylum-seekers are still find themselves in a limbo where they have neither rejected their old loyalties nor adopted new ones. Perhaps this contributes to the fear of asylum-seekers, as they are viewed as having a volatile identity.

To understand how asylum-seekers are perceived as a threat to national identity, one must look historically. Australia’s national identity is rooted in white superiority, going back to immigration schemes in the 1800s. ‘Assisted passages’ were the most common way to migrate to Australia between 1831 and 1982, and these were “rarely extended to non-British persons” (McMaster, 2002, p. 281). The first non-white people that came to Australia were Chinese migrants during the gold rush of the mid 1800s, resulting in racial hostility, racial exclusion and subsequent fear that “the handful of white people would be ‘swamped’ by the hordes from the north” (McMaster, 2002, p. 282). Fears of immigrants quickly turned into exclusionary policies in the colonies of Queensland and New South Wales. Burke (2008) argues that it was fear of Asian invasion that prompted the colonies’ drive for Federation

McMaster (2002) argues that contemporary fears of asylum-seekers are entrenched in Australian society and originated as early as Federation in 1901. After becoming an independent state in 1901, Australian policy focussed on nation-building and the first Act passed was the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 (McMaster, 2002). This Act aimed to protect the newly formed nation against threats to social cohesion and reflected a broader fear of invasion from Asia. It incorporated the White Australia Policy, which continued into the early 1970s even as the government widened the immigration catchment area from Britain to Northern and Southern European countries. Immigration to Australia remained largely white, even as Australia admitted more than 170,000 (non-Asian) refugees before 1954 (McMaster, 2002). The persistence of an Australian national identity that is rooted in a racist sense of superiority and the exclusion of non-white nationals helps to explain why non-white asylum-seekers are labelled as a threat to this racial homogeneity.

Asylum-seekers may be presented on a threat to national identity because they may be unwilling to integrate into society (McDonald, 2011). Today, asylum-seekers are perceived as a threat to Australian national identity and way of life (McKay, Thomas and Kneebone, 2011). McDonald (2011) argues that the Australian nation was built on ‘borderphobia’ and thus had a strong fear of the ‘other’. McMaster (2002) summarises this well when he states, “asylum-seekers have been demonised and, like the ‘hordes’, defined as the other’ – to be feared and used as scapegoats in the name of border control and national security” (p. 281). Anderson and O’Dowd (1999) explore how social and communal boundaries are viewed as increasingly separate from physical territorial borders, and the “nation-state ideal of cultural homogeneity and centralized political power is both confirmed and disrupted at the border” (p. 596). They go on to explore how borders “generate a great dynamic for state projects of internal homogenization” (Anderson & O’Dowd, 1999, p. 598), signifying power and exclusion. McNevin (2007) discusses how this creates an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mentality that threatens national cohesion due to a moral and cultural ‘other-ness’. Lastly, Innes (2010) explores how it is not the individual that is perceived as a threat, but rather the “threatening homogenous collective” (p. 461).

Economic Threat

Asylum seekers are labelled as a threat economically, both to the individual and to the state. For the individual, the threat from asylum-seekers comes from the idea that addition people in the country will take away employment opportunities from current citizens. Huysmans (2000) explored how “scarcity makes immigrants and asylum-seekers rivals to national citizens in the labour market” (p.767). In Australia, a fear of the economic power of immigrants started in the mid 1800s, when Chinese immigrants working in the gold mines created feelings of economic insecurity among the settlers (McMaster, 2002).

Secondly, there is concern about the time spent in the host country while a claim is being processed, especially if the asylum-seekers is found not to be a legitimate refugee, due to the high costs of asylum processing (Kaye, 2013). The idea that the asylum-seeker is using valuable state resources, through the welfare system, is a concern that continues beyond the initial claim (Innes, 2010). Here the fear is that asylum-seekers are lazy and will rely on unemployment benefits provided by their host state, contributing to “[o]verwhelming state’s capacity to provide public services [which] can lead to conflicts over resources” (Adamson, 2006, p. 176). Innes (2010) discusses how the fear comes from the “encroachment upon the ability of a state to confine its resources to its citizens” (p. 461), and a common misconception that asylum-seekers will have priority in the welfare system (Huysmans, 2000).

The irony of the perceived economic threat is that detention of asylum-seekers “represents a serious financial cost to tax-payers” (Nakache, 2011, p. 94). In the 2018 Financial year, the US Department of Homeland Security is set to spend 3 billion on immigration detention (Benenson, 2018), and Australia’s detention program cost 2.5 billion in 2017 (Karp, 2018). Community ‘detention’ whilst awaiting the asylum decision is a third of the cost (Karp, 2018).

How Are Asylum-Seekers Labelled as a Threat?

Speech Acts as Technique of Securitisation

According to securitisation theory, it is through speech acts that issues become perceived of as threats to a political community (McDonald, 2011). The rhetoric of national leaders and politicians is extremely important in creating the idea of a security threat, because of the constructed nature of security (McDonald, 2011). Therefore the power of discourse is that it labels something as a threat, so it becomes one (Waever, 2004). In this sense, it is both productive and reproductive; political rhetoric identifies a threat to the nation, and through the very process of this identification, the threat is created, and through its perceived existence, the threat is heightened. The role of the media in picking up on and repeating certain rhetoric is also important in this discussion.

Illegality

In both the United States and Australia, a rhetoric of illegality is applied to asylum-seekers, whereby their entry into the country through illegal pathways renders their asylum request illegal also. Hamlin (2012) states that the US rhetoric of illegality has a long history and has always been applied to Haitians and Central Americans. This rhetoric is problematic because so-called ‘illegal pathways’, such as coming by boat to Australia or not crossing the Mexico-US border at an official port of entry, are sometimes the only option available to asylum-seekers.

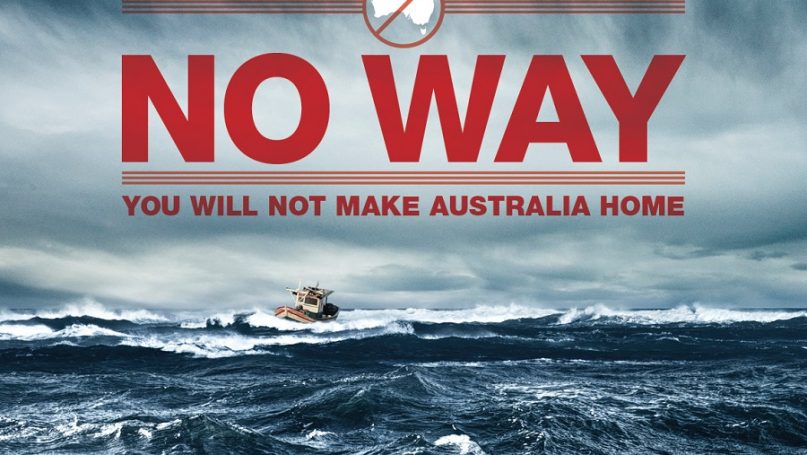

In Australia, the words ‘boat people’, ‘refugee’ and ‘illegals’ are used interchangeably by the media, and McKay, Thomas and Blood (2011) found that other inaccurate and derogatory terms such as ‘illegal asylum-seeker’ or ‘illegal refugee’ have been utilised. These terms, and the rhetoric that coming by boat breaches Australian law, implies that the actions of asylum-seekers are illegal. McKay, Thomas and Blood (2011) analyse how the Australian media played on social anxiety, moral panic and the potential risk that asylum-seekers pose for Australian society. In a welcome video displayed in detention centres to asylum-seekers that had arrived on Manus Island and Nauru, the then Immigration Minister Scott Morrison is quoted as saying, “You have been brought to this place here because you have sought to enter Australia illegally by boat” (‘Very Concerned’, 2015).

In the US, the rhetoric of illegality is often employed by the media to describe undocumented or irregular migrants. Fox News has been referring to the 2018 ‘Migrant Caravan’ as ‘illegal immigrants’, even before they reached the US border where most of them were planning to legally seek asylum (Mikelionis, 2018). The use of this terminology is deliberate and powerful in suggesting that migrants are breaking the law, and therefore are criminals. Despite the inherent contradiction of “illegal asylum-seekers”, as it is not illegal to seek asylum, the rhetoric of illegality persists and is advanced by Donald Trump.

Criminality

The rhetoric of illegality helps create a perception that asylum-seekers are criminals. As John Oliver summarised it, “[c]rossing the border is a crime, therefore anyone crossing it is a criminal, and since all criminals are dangerous, anyone crossing the border is a dangerous criminal.” (LastWeek Tonight, 2018).

This idea of criminality is advanced by Trump by repeatedly suggesting that the Migrant Caravan is joined by “criminals and unknown Middle Easterners” in a tweet on October 22nd 2018 (Trump, 2018), adding later that “many Gang Members and some very bad people are mixed into the Caravan” (Smith, 2018). Besides the racist profiling of all people from the Middle East as criminals, the labelling of migrants as criminals has been picked up news outlets such as Fox News who discussed the “criminal elements and a known convicted murderer” in the caravan (Fox News, 2018).

Beyond the Migrant Caravan, Trump has suggested that all Mexicans attempting to enter the United States are drug dealers, rapists and criminals. In a speech during his presidential campaign in 2016, Trump stated:

When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you. They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.

Donald Trump, June 16, 2015 (“Donald Trump speech”, 2018)

The rhetoric here is that asylum-seekers are gang members, intent on trafficking drugs into the country. A fear of drug trafficking networks, exemplified by the ‘war on drugs’, as well as general violence is linked to asylum seekers. Trump exclaimed in December 2018, “the people in this country don’t want criminals, and people that have lots of problems and drugs pouring into our country … shut it down for border security” (Jacobs, 2018).

In Australia, the criminality of asylum-seekers arriving by boat is twofold. Firstly, anyone found to assist asylum-seekers in their journey can be charged with a criminal offense. Thereby not only is arriving by boat illegal but assisting or encouraging anyone else to do the same is punishable by law. In his address to the new arrivals in detention centres, Morrison has stated:

If they have sought to support you or anyone else, they will come to the attention of the police, and may face charges and if convicted they will serve jail time, and if they are on a visa that visa will be cancelled.

Scott Morrison, August 19, 2015 (‘Very Concerned’, 2015)

Secondly, the criminality debate has been framed as a war against people smuggling. As McKay, Thomas and Blood (2011) explored, the media presented people smugglers as the new threat to Australians. Here it is the criminal networks of people smugglers that “Australia must wage a war against” (ABC News, 2013). Scott Morrison, in an interview with ABC News, repeatedly referred to the war against people smugglers and the popularised slogan of “we will stop the boats” (ABC News, 2013). The government presents stopping the boats from arriving in Australia as winning the ‘fight’ against people smugglers, thereby equating asylum-seekers with the criminal network of people smugglers, or as having been tricked by the criminals. Scott Morrison in his address to new arrivals has stated, “You have been told a lie by people smugglers. They have taken advantage of you. They have ripped you off” (‘Very Concerned’, 2015). Therefore asylum-seekers are either criminal people smugglers, or lacking agency in their stupidity.

A war on people smugglers is justified by politicians for the safety of the asylum-seekers. Scott Morrison has been quoted as saying that the “sea is a dangerous place” (ABC News, 2013), repeating the idea that stopping the boats is saving lives. Bill Shorten has been quoted as saying, “I think it’s clear that the combination of regional settlement, with offshore processing, and also the turn back policy, is defeating people smugglers” (Anderson, 2015).

Invasion/Sovereignty

A rhetoric of dangerosity in the United States refers specifically to the Migrant Caravan as an invasion, alluding to the idea that people seeking asylum are a threat when they breach the sovereignty of national borders. Trump tweeted on October 29th, 2018 that “[t]his is an invasion of our Country and our Military is waiting for you!” (Smith, 2018). The urgency of this invasion was highlighted when he said, “Oh, they’ll be here fast. They’re trying to get up any way they can” (Smith, 2018b). Trump further heightened the sense of urgency when he called the caravan a national emergency (Trump, 2018). Mike Pompeo, US Secretary of State, called the caravan an attempt to “violate the sovereignty of Mexico” in an interview with Fox News (‘Bctvguy’, 2018) and this language of invasion has been picked up by news outlets. Newt Gingrich, a Fox News correspondent, stated that “this is an invasion … attacking the United States sovereignty” (‘Bctvguy’, 2018).

The health of the caravan migrant has also been used in rhetoric to heighten fears of a biological invasion and present asylum-seekers as a threat to the health and safety of Americans. Former Immigration Minister David Ward was quoted as saying, “They’re coming in with diseases such as smallpox and leprosy and TB that are going to infect our people in the United States” (Smith, 2018b).

Australian rhetoric on sovereignty is exemplified in the name of the current border policy, Operation Sovereign Borders. Scott Morrison has repeatedly reiterated the importance of national security in the Pacific, but without explicit mention to asylum-seekers. In his first presentation on Australia’s foreign policy as Prime Minister, he stated that Australia’s national security relies on the Pacific in ensuring that the Pacific is “secure nationally, stable economically and sovereign politically” (ABC News, 2018). As spokesperson for immigration for the Opposition in 2013, Morrison also referred to the turning back of boats policy as necessary for the “safety of our own people”, as well as it being our “sovereign decision” (ABC News, 2013).

There is also an increasingly militarised rhetoric in Australian politics towards asylums seekers. Politicians refer to the interdiction of boats at sea as ‘missions’ and won’t reveal the specific policies, using a language of secrecy and security that heightens the perception of a threat to national security. Scott Morrison has said that he can’t reveal “moves made at sea and the tactics that compromise the mission” (ABC News 2013).

Securitisation Outcomes in Policy

Normalization of Extraordinary Measures

The eventual outcome of securitisation is the normalisation of extraordinary measures outside the political norm. This can be manipulated by politicians as a means to achieve an end, such as a political goal. As McDonald (2011) has summarised, “political actors attempt to use the language of security and threat to enable specific political responses” (p. 283). By creating a sense of urgency for the threat faced, more extreme policies can be passed as a response to this threat without too much political disapproval.

The extraordinary responses to asylum-seekers, in response to their threat to national security, take the form of the increased militarisation of asylum issues, mandatory detention policies, the interdiction of migrant vessels and the refusal to resettle those found to be legitimate refugees.

Militarisation

The rhetoric of invasion outlined earlier justifies a military response, because asylum-seekers are presented as a military problem. The response of the US government to the migrant caravan has been to send active duty troops to the US-Mexico border in anticipation for their arrival (Smith, 2018). The exact number of military personal deployed has received mixed reports in the media, but President Trump made threats of up to 15,000 (Smith, 2018b). The deployment of potentially armed military personnel to confront migrants who are unarmed and seeking protection is a clear indication of the militarisation of the response to asylum-seekers. In November 2018, American border officers used military style force on migrants attempting to cross the Mexico-US border to seek asylum (“US officers”, 2018). In response to the Migrant Caravan, Mexican authorities are increasingly using military force, with one migrant passing away in November after being hit by a rubber bullet when trying to enter Mexico (Smith, 2018b). Trump’s plan to build a wall along the Mexican border is a militarised image and alludes to a fortification of the United States’ border in line with traditional military defence.

Australia’s Operation Sovereign Borders policy similarly militarises the response to asylum-seekers through the deployment of the navy to police Australian waters. They navy vessels are instructed to either turn around the boats or escort them to an offshore processing facility to ensure migrants don’t reach Australian land (Doherty, 2017). This is a clear example of the use of the military to deal with a humanitarian issue, justified using the rhetoric of ‘war’ against people smugglers. If people smuggling is a crime, this justifies a militarised response.

Australia and the United States are not the first, or only, examples of the militarisation of asylum-seekers. Italy’s Mare Nostrum Operation involving their naval and air force personnel in the Mediterranean Sea saved thousands of migrants and brought them to the Italian coast (Taylor, 2018). The difference between the Italian deployment of the military and the Australian and American is that whilst the Italian navy appeared to adopt the role of humanitarians in conducting search and rescue operations, the US and Australia deployed the military as a defensive tool to strengthens one’s borders and keep migrants out. Arguably, Australia’s operations at sea have risked lives rather than saved them (Doherty, 2017).

Detention Centers

A detention clause has existed since 1901 for “unlawful non-citizens that seek to enter/remain in Australia without a valid visa or entry permit” (McMaster, 2002, p.283). Australia currently has one offshore detention centre, on Nauru, a small island state in the Pacific Ocean (Davidson, 2018). Nauru was first used as an offshore processing centre for asylum-seekers after the Tampa Incident in 2001 and is used by the Australian government to side-step its responsibilities under international law (Doherty, 2016). The detention centre on Nauru run by the Australian government has raised a multitude of human rights concerns, include indefinite arbitrary detention, detention of children and unsanitary and crowded living conditions. The Nauru Files, uncovered by The Guardian in 2016, detailed reports of abuse of children, severe mental health emergencies including suicide and self-harm and cases of sexual abuse (Evershed et al., 2016). Despite the publication of these abuses by the press and subsequent protest by human rights groups the detention facility remains in use on Nauru.

The Australian government closed a detention facility on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea, in 2017 and attempted to move the remaining refugees and asylum-seekers to alternative housing on the island (Fox, 2018). However this alternative was deemed unsafe by some, and hundreds of men remained in the rundown detention centre without access to electricity or running water (Fox, 2018). In November 2018, some refugees remaining on Manus Island were transferred to Nauru because of a worsening health crisis on Manus (Davidson, 2018). These individuals have been granted refugee status, can never resettle in Australia and are awaiting third-country resettlement (Davidson, 2018). The resettlement deal with the United States for 1,200 refugees is in place but moving slowly (Davidson, 2018).

A related extraordinary measure put in place by the Australian government appears to be the censorship in the press in relation to Nauru island. Visa costs for foreign journalists to Nauru cost 8,000 US dollars, and applications for this visa are difficult, if not impossible, to submit (Doherty, 2016). Secondly, the Australian Border Force Act 2015, article 42,bans those working in offshore detention facilities to disclose ‘protected information’, carrying a penalty of imprisonment for two years (Doherty, 2016).

The United States utilises immigration detention centres along the Mexican border that similarly breach the human rights of detainees (Gumbel, 2018). Under a new “zero tolerance policy” for irregular border crossings initiated by the government in April 2018, thousands of migrants were charged with illegal border crossing and sentenced to between 2 days and 6 months in prison (Gumbel, 2018). After they are released from prison, most will most likely be deported or wait in immigration detention whilst their asylum claim is being processed.

Under this policy, children have been held in detention separately as the parents go through the judicial process and end up in federal prisons (Holpuch, 2018). The prolonged separation of children as young as 18 months from their parents can cause irreparable harm psychologically doctors have reported, condemning the policy as cruel (Holpuch, 2018). Australia has similarly been criticised for causing harm to minors in detention centres (“Human rights groups”, 2018).

Detention is also an aspect of militarisation, or at least the criminalisation discussed earlier – detention centres, despite having a different name, are essentially prisons for migrants. As McMaster (2002) summarised, “since September 2001 detainees have been irresponsibly conflated with terrorists, so that the use of detention has acquired a military and defence rational” (p. 287-288). Detention further serves to dehumanise asylum-seekers through the conditions they are placed in, with US Immigration detention being likened to cages (Holpuch, 2018).

Refoulement

In Australia, a catch-cry of ‘turning back boats’ for the safety of asylum-seekers has caused migrant boats to be interdicted at sea. The policy is to not allow migrants to board Australian vessels but provide lifeboats to tow them back to where they came from (Schloenhardt & Craig, 2015). If entire boats of asylum-seekers are turned away, this means individual case assessment does not occur, resulting in some genuine refugees deserving protection being turned away. This policy, and similar policies by implemented by Italy to push back migrant boats in the Mediterranean (Agerholm, 2018) breach the international law principle of non-refoulement, which dictates that refugees may not be returned to the country in which they face persecution (United Nations, 1951). Under Australia’s hard-line border policy, even those found to have a legitimate fear of persecution, and thus given refugee status, will never be settled in Australia, instead opting for a ‘third country’ resettlement solution (Anderson, 2015).

In the United States, the expedited justice system put in place for the “zero tolerance” policy meant most migrants pleaded guilty to misdemeanour of crossing border illegally, resulting most likely in deportation after serving their misdemeanour sentence. 96.5% of migrants surveyed by the guardian pleaded guilty to the misdemeanour, influenced by lack of information and confusing processes (Solon et al., 2018). This mean that even those genuinely in need of protection may be deported.

Conclusions: The Importance of Context

These measures are extraordinary both in their disregard for international refugee and human rights law, in their inhumane treatment of those fleeing from persecution and in their extreme nature. They violate international agreements, as well as causing psychological and physical harm to those seeking asylum. Importantly, these measures mean that Australia and the United States do not allow asylum seekers fair and thorough evaluations of their cases, and thus do not uphold their obligations under international law to protect refugees. This raises the question of how these policies continue without serious backlash, and how the securitised rhetoric is received by the population. Second wave securitisation theorists have stated that the mere existence of a speech act is not enough for securitisation to occur. Rather, the right conditions must exist for the threats to be believed (McDonald, 2008). The audience’s receptiveness to securitisation rhetoric is central in the power that it holds – but which conditions make people more susceptible to securitised rhetoric?

McDonald (2008) discusses how perceived moments of political crisis influence securitisation. Heightened anxiety in society regarding migration, and the role of the 2015 ‘migration crisis’ in Europe, play a central role. Europe saw the highest level of asylum-seekers since the Second World War, with 1.8 million refugees arriving in Europe since 2015 (Henley, 2018). Migration has dominated political rhetoric, with the idea of “waves of asylum seekers” coming from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq feeding populist rhetoric (Nguyen & Summermatter, 2015). Although the US and Australia were less affected by the crisis, the securitisation of asylum seekers is in line with populist and anti-migration in Hungary, Italy and Germany (“Europe and Nationalism, 2018”). The urgency of that crisis justifies the urgency of policies and rhetoric that demand that something must be done, now. Securitised speech acts are a welcome answer to people’s anxieties, whilst simultaneously feeding these anxieties, creating a cycle that may be difficult to break.

Secondly, the current discussion surrounding ‘Fake News’, especially in the United States, heightens the idea that the threat does not have to exist for it to be perceived as such. Increased distrust of the media and misinformation means imagined threat are more likely to be believed, and asylum-seekers more likely to be perceived as a threat when they are not. Thirdly, the strength of identity narratives is an important condition for securitisation. Identity narratives make people more likely to accept securitised rhetoric (Wæver 2000). McDonald (2008) stresses the importance of existing narratives of sovereignty and identity, suggesting that these two elements are not only invoked in securitised rhetoric, but are underlying conditions.

An outcome of securitised rhetoric of asylum seekers beyond policy is a wider rejection from society by the individuals in that society. This raises the question of who can securitise? As argued by Seidman-Zager (2010), it is not just state representatives, or elites, that can take part in securitised rhetoric from a position of power. Instead the role of individuals perpetuating ideas about asylum seekers as threats must be examined. Countering rhetoric, for example from NGOs or activists, could also be considered in further analysis on society’s role in securitisation.

The policies in effect in the United States and Australia are legitimated through the securitised rhetoric of illegality, criminality and invasion, which present asylum-seekers as threats to national sovereignty, national identity, individual safety and economic resources. As both nations have been condemned for their refugee policies by the United Nations and other refugee and human rights advocacy groups, the broader question of how this securitised rhetoric is able to continue is left unanswered. Further research could explore how securitised rhetoric of asylum-seekers is normalised and perpetuated not only by elites and the media, but by individuals in our everyday lives. Security, and threat, beyond the speech acts of political leaders, takes on a life of its own, with mutations beyond the intent of the initial speech.

References

ABC News (Australia). (2013, July 18). Scott Morrison describes ‘war against people smuggling’ . Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aWraKw7BqfY

ABC News (Australia). (2018, November 7). Scott Morrison to upgrade Australia’s foreign policy FULL SPEECH ABC News . Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iaAEnJavJMU

Adamson, F. (2006). Crossing borders: international migration and national security. International security, 31(1), 165-199.

Agerholm, H. (2018, May 8). Italy sued over migrant ‘push back’ deal with Libya after 20 migrants drown in the Mediterranean. The Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/italy-libya-migrant-refugee-push-back-deal-mediterranean-a8342056.html

Anderson, J. & O’Dowd, L. (1999). Borders, Border Regions and Territoriality: Contradictory Meanings, Changing Significance. Regional Studies, 33(7), 593-604.

Anderson, S. (2015, July 24). Explore the history of Australia’s asylum seeker policy. SBS. Retrieved from https://www.sbs.com.au/news/explainer/explore-history-australias-asylum-seeker-policy

Barnett, M. (2011). Empire of humanity: A history of humanitarianism. Cornell University Press.

‘Bctvguy’ (2018, October 20). Immigrant INVASION Caravan – 19 October 2018 . Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KFCRD3ulEew

Benenson, L. (2018, May 9). The Math of Immigration Detention, 2018 Update: Costs Continue to Multiple. The National Immigration Forum. Retrieved from https://immigrationforum.org/article/math-immigration-detention-2018-update-costs-continue-mulitply/

Brzoska, M. (2009). The securitization of climate change and the power of conceptions of security. S&F Sicherheit und Frieden, 27(3), 137-145.

Buchanan, S., Grillo, B. and Threadgold, T. (2003). What’s the Story? Results from Research into Media Coverage of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK. Article 19. Retrieved from https://www.article19.org/data/files/pdfs/publications/refugees-what-s-the-story-.pdf

Burke, A. (2001). In fear of security: Australia’s invasion anxiety. Sydney: Pluto Press.

Burke, A. (2008). Fear of Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buzan, B. (1991). People, States, and Fear, Hemel Hempstead. Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Buzan, B., Wæver, O., & De Wilde, J. (1998). Security: a new framework for analysis. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Carrapico, H. (2014). Analysing the European Union’s responses to organized crime through different securitization lenses. European Security, 23(4), 601-617.

Crick, E. (2012). Drugs as an existential threat: An analysis of the international securitization of drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy, 23(5), 407-414.

Davidson, H. (2018, November 29). Group of Manus Island refugees move to Nauru amid worsening health crisis. The Guardian. Retrieved from

Doherty, B. (2016, August 9). A short history of Nauru, Australia’s dumping ground for refugees. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/10/a-short-history-of-nauru-australias-dumping-ground-for-refugees

Doherty, B. (2017, October 29). Australia’s asylum boat turnbacks are illegal and risk lives, UN told. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/oct/30/australias-asylum-boat-turnbacks-are-illegal-and-risk-lives-un-told

Donald Trump speech, debates and campaign quotes. (2018, November 9). Newsday. Retrieved from https://www.newsday.com/news/nation/donald-trump-speech-debates-and-campaign-quotes-1.11206532

Europe and nationalism: A country-by-country guide. (2018, September 10). BBC. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-36130006

Evershed, N., Lui, R., Farrell, P. & Davidson, H. (2016). The lives of asylum seekers in detention detailed in a unique database. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/ng-interactive/2016/aug/10/the-nauru-files-the-lives-of-asylum-seekers-in-detention-detailed-in-a-unique-database-interactive

Fisher, J. & Anderson, D. (2015). Authoritarianism and the securitisation of development in Africa. International Affairs, 91(1), 131-151.

Fox, L. (2018, October 31). Manus Island detention centre to permanently close today, 600 men refusing to leave. ABC News. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-10-31/manus-island-detention-centre-to-close-at-5pm-today/9102768

Fox News. (2018, December 3). Migrants gather at a new shelter area in Tijuana . Retrieved from https://video.foxnews.com/v/5974779306001/?#sp=show-clips

Gibney, M. (2004). The ethics and politics of asylum: Liberal democracy and the response to refugees. Cambridge University Press.

Gumbel, A. (2018, September 12). ‘They were laughing at us’: immigrants tell of cruelty, illness and filth in US detention’. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/sep/12/us-immigration-detention-facilities

Hamlin, R. (2012). Illegal refugees: Competing policy ideas and the rise of the regime of deterrence in American asylum politics. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 31(2), 33-53.

Henley, J. (2018, November 21). What is the current state of the migration crisis in Europe? The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jun/15/what-current-scale-migration-crisis-europe-future-outlook

Herlihy, J., & Turner, S. (2007). Asylum claims and memory of trauma: sharing our knowledge. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(1), 3-4.

Holpuch, A (2018, June 18). Why are families being separated at the US border? The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/jun/18/why-are-families-being-separated-at-the-us-border-explainer

Human rights groups call for children to be taken off Nauru. (2018, August 20). BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-45244149

Huysmans, J. (2000). The European Union and the securitization of migration. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 38(5), 751-777.

Huysmans, J. and Buonfino, A. (2008). Politics of Exception and Unease: Immigration, Asylum and Terrorism in Parliamentary Debates in the UK, Political Studies 56(4), 766-788.

Innes, A. (2010). When the threatened become the threat: The construction of asylum seekers in British media narratives. International Relations, 24(4), 456-477.

Jacobs, B. (2018, December 11). Nancy Pelosi calls public clash with Trump a ‘tickle contest with a skunk’ – as it happened. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/live/2018/dec/11/donald-trump-latest-news-manafort-google-live

Kagan, M. (2002). Is truth in the eye of the beholder-objective credibility assessment in refugee status determination. Georgetown Immigration Law Journal, 17, 367.

Karp, P. (2018, January 5) Australia’s ‘border protection’ policies cost taxpayers $4bn last year. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/jan/05/australias-border-protection-policies-cost-taxpayers-4bn-last-year

Kaye, R. (2013). Blaming the victim’: an analysis of press representation of refugees and asylum-seekers in the United Kingdom in the 1990s. In King, R. & Wood, N.

(Eds.). Media and Migration: constructions of Mobility and Difference, (pp. 63-80). Routledge.

Kelle, A. (2007). Securitization of international public health: implications for global health governance and the biological weapons prohibition regime. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 13(2), 217-235.

Key quotes: President Bush’s Speech. (2005, January 20). BBC. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/4192855.stm

Last Week Tonight. (2018, November 4). Family Separation: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO) . Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ygVX1z6tDGI

Leboeuf, A., & Broughton, E. (2008). Securitization of health and environmental issues: process and effects. A research outline. Health and Environment Working Document,

Institut Français des Relations Internationales. Retrieved from https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/Securitization_Health_Environment.pdf

Leffler, M. (1984). The American Conception of National Security and the Beginnings of the Cold War, 1945-48. The American Historical Review, 89(2), 346-381.

Lo Yuk-ping, C., & Thomas, N. (2010). How is health a security issue? Politics, responses and issues. Health Policy and Planning, 25(6), 447-453.

Macintyre, S. (2009). A Concise History of Australia (3rd ed.). Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Malloch, M. and Stanley, E. (2005) The Detention of Asylum Seekers in the UK: Representing Risk, Managing the Dangerous. Punishment Society, 7(1), 53-71.

McDonald, M. (2008). Securitization and the Construction of Security. European Journal of International Relations, 14(4), 563-587.

McDonald, M. (2011) Deliberation and Resecuritization: Australia, Asylum- Seekers and the Normative Limits of the Copenhagen School, Australian Journal of Political Science, 46(2), 281-295.

McKay, F., Thomas, S. and Kneebone, S. (2011). ‘It would be okay if they came through the proper channels’: Community perceptions and attitudes toward asylum seekers in Australia. Journal of Refugee Studies, 25, 113–33.

McKay, F., Thomas, S. & Blood, R. (2011). ‘Any one of these boat people could be a terrorist for all we know!’ Media representations and public perceptions of ‘boat people’ arrivals in Australia. Journalism, 12(5), 607-626.

McKenzie, J. & Hasmath, R. (2013) Deterring the ‘boat people’: Explaining the Australian government’s People Swap response to asylum seekers. Australian Journal of Political Science, 48(4), 417-430.

McLean, D. (2001). Australia in the Cold War: A Historiographical Review. The International History Review, 23(2), 299–321.

McMaster, D. (2002). Asylum-seekers and the insecurity of a nation. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 56(2), 279-290.

McNevin, A. (2007) The Liberal Paradox and the Politics of Asylum in Australia, Australian Journal of Political Science, 42(4), 611-630.

Mikelionis, L. (2018, December 4). Caravan migrants begin to breach border as frustration with slow asylum process grows. Fox News. Retrieved from https://www.foxnews.com/world/caravan-migrants-breach-us-border-amid-anger-from-slow-asylum-seeking-process

Miriam-Webster. (2018). Existential. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/existential

Nakache, D. (2011). The Human and Financial Cost of Detention of Asylum-seekers in Canada: written for the UNHCR. Retrieved from https://www.refworld.org/docid/4fafc44c2.html

Nguyen, D & Summermatter, S. (2015, December 18). 2015: when the wave of migrants hit Europe. Swiss Info. Retrieved from https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/politics/data-story_2015-when-the-wave-of-migrants-reached-europe/41844230

Ogata, S., & Cels, J. (2003). Human security-Protecting and empowering the people. Global Governance, 9, 273.

Pöllabauer, S. (2004). Interpreting in asylum hearings: Issues of role, responsibility and power. Interpreting, 6(2), 143-180.

Schain, M. (2010). Managing Difference: Immigrant Integration Policy in France, Britain. and the United States. Social Research, 77(1), 205–236.

Schloenhardt, A., & Craig, C. (2015). ‘Turning Back the Boats’: Australia’s Interdiction of Irregular Migrants at Sea. International Journal of Refugee Law, 27(4), 536-572.

Seidman-Zager, J. (2010). The securitisation of asylum: protecting UK residents. (Refugee Studies Centre Working Paper). Retrieved from University of Oxford Refugee Studies Centre https://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/publications/the-securitization-of-asylum-protecting-uk-residents

Smith, D. (2018, October 29). Trump accused of stoking immigration fears by sending 52,000 troops to border. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/oct/29/trump-immigration-troops-border-midterms

Smith, D. (2018b, October 31). Trump further stokes immigration fears by saying he’ll send 15,000 troops to order. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/oct/31/trump-migrant-caravan-immigration-us-troops-mexico

Solon, O., Wong, J., Duncan, P., Katcher, M. Timmons, P. & Morris, S. (2018, October 14). 3,121 desperate journeys: Exposing a week of chaos under Trump’s zero tolerance. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2018/oct/14/donald-trump-zero-tolerance-policy-special-investigation-immigrant-journeys

Southam, K. (2011). Who am I and Who Do You Want Me to Be-Effectively Defining a Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Social Group in Asylum Applications. Chicago-Kent Law Review, 86, 1363.

Steckel, R. H. (1989). Household migration and rural settlement in the United States, 1850-1860. Explorations in Economic History, 26(2), 190-218.

Taylor, A. (2018, April 20). Italy ran an operation that saved thousands of migrants from drowning in the Mediterranean. Why did it stop?. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/04/20/italy-ran-an-operation-that-save-thousands-of-migrants-from-drowning-in-the-mediterranean-why-did-it-stop/?utm_term=.71949860856b

Thomson, J. (1995). State Sovereignty in International Relations: Bridging the Gap between Theory and Empirical Research. International Studies Quarterly, 39(2), 213-233.

Torpey, J. (1999) The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship, and the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trump, D. [realDonaldTrump]. (2018, October 22). Sadly, it looks like Mexico’s Police and Military are unable to stop the Caravan heading to the South Border of the United States. Criminals and unknown Middle Easterners are mixed in. I have alerted Border Patrol and Military that this is a National Mergy. Must change laws! [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1054351078328885248?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1054351078328885248&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cnbc.com%2F2018%2F10%2F22%2Ftrump-says-unknown-middle-easterners-are-mixed-in-migrant-caravan.html

United Nations. (1951). The Refugee Convention. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/4ca34be29.pdf

United States Census Bureau. (2017). Population. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/IPE120217

US officers fire teargas at migrant caravan – video. (2018, November 26). The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/global/video/2018/nov/26/us-officers-fire-tear-gas-at-migrant-caravan-video

‘Very Concerned’. (2015, August 19). Australian Immigration Minister Scot Morrison tells asylum seekers to go home . Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mq3ijRs-ilw

Wæver, O. (2004, March 20) ‘Aberystwyth, Paris, Copenhagen: New Schools in Security Theory and the Origins between Core and Periphery’. Paper presented at International Studies Association, Montreal.

Wæver, O. (2000). The EU as a Security Actor: Reflections from a Pessimistic Constructivist on European Integration. In M. Kelstrup and M. Williams. (Eds). International relations theory and the politics of European Integration. (pp. 250-294).London: Routledge.

Williams, P. D. (2007). Thinking about security in Africa. International Affairs, 83(6), 1021-1038.

Notes

[1] Mohamedou, M. (2018, October 22). The Post-Cold War Era and Interventionism: Session Five. [Class PowerPoint]. State-Building and War-Making in the Developing World, Graduate Institute Geneva.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Mohamedou, M. (2018, October 29). The Post-Cold 9/11 World and Securitization: Session Six. [Class PowerPoint]. State-Building and War-Making in the Developing World, Graduate Institute Geneva.

[4] Mohamedou, M. (2018, October 22). The Post-Cold War Era and Interventionism: Session Five. [Class PowerPoint]. State-Building and War-Making in the Developing World, Graduate Institute Geneva.

[5] For further literature on the subjectivity of asylum decisions, see Kagan, 2002; Pöllabauer, 2004, Herlihy & Turner, 2007 or Southam, 2011.

Written at: Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies

Written for: Mohammad-Mahmoud Ould Mohamedou

Date written: December 2018

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Queer Asylum Seekers as a Threat to the State: An Analysis of UK Border Controls

- The Legitimisation of Australia’s Deterrent Migration Policy

- Australia on the United Nations Security Council 2013-14: An Evaluation

- Migration in the European Union: Mirroring American and Australian Policies

- Australia: International Agreements as Obligation in the Case of Climate Change

- Climate Security in the United States and Australia: A Human Security Critique