When it comes to discussing the events of September 2001 between the members of my family, my mother always recalls how when she first saw coverage of the attacks in the television. For a longer while she thought she was watching just another action movie. It was only as she received a call from my father when she realised that the footage of planes crushing into a skyscraper or people jumping out of the windows desperately trying to save their lives, was in fact live footage from New York City, Pennsylvania and Washington, D. C. The series of events which certainly resembled a film more than the reality set in motion a process of deep changes in the consciousness of the mainstream public, introducing multiple sets of institutional practices (including military and intelligence operations, special government bodies or legislation) as well as an accompanying discursive project (Jackson, 2005). Although the atrocity of terrorism is undeniable and utterly horrendous, the method of dealing with it is an issue of contestation for many. According to Bonafede (2002, p. 162) state practice post-9/11 shifted towards a loosening of the proportionality regulation on the right to self-defence in terms of responding to international terrorism. Some important questions to consider here, include for instance whether the events of September 11 justify the extent of US military interventions around the globe? Was the American government still acting within the bounds of self-defence? Certainly those and many other questions are terribly difficult to give a simple answer to, as the concept of proportionality in international relations is deeply complex. This essay shall argue that the ‘war on terror’ was not a proportionate way to combat terrorism. It served as a mean of securitising global terrorism as a threat significant and dangerous enough to legitimise the extraordinary use of force undertaken by the American government. The formalisation of terrorism as a war can thus be considered as a crucial mode of naturalising a new social reality which allows for the use of extraordinary measures, effectively suspending the normal political functions of a state. This essay will make use of the securitisation theory developed by the Copenhagen School, which I shall elucidate in line with an analysis of the discourse of Bush’s administration, making use of the Foulcauldian concept of discourse, understood as a powerful set of assumptions, expectations or explanations, which define mainstream social or cultural reality through language and practices (Hodges, 2011).

Background

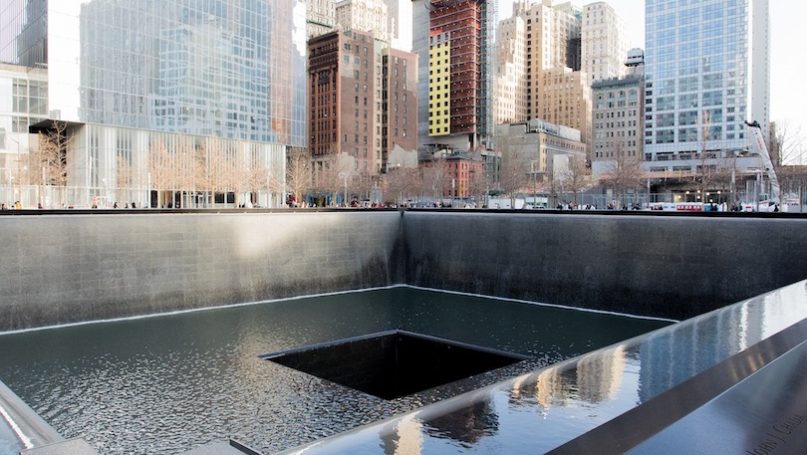

The events of September 2001 can certainly be considered as one of the most ground-breaking in the 21st century history of the world, triggering profound military, political and diplomatic changes. In the morning of 11 September hijacked commercial planes destroyed the World Trade Centre in New York and parts of Pentagon, attacking the key economic and military symbols of American power, killing about 3000 people and injuring over 25 000 (Suganami, 2003 p.3, Morgan 2009, p.222). As Gokay and Walker (2003, p.1) explain “No one predicted the tragic events of 11 September. They were not inevitable but neither did they come out of blue. They were the product of long-term structural developments and conjectural individual actions that might have turned out differently.” In 2002, Osama bin Laden – the founder of al-Qaeda, wrote the “Letter to America” (2002) where he stated the motives for declaring the holy war against the US, which included American support of Israel or the sanctions and operations in Iraq, Somalia or India. Bin Laden’s messages point to his hope for ‘destroying and bankrupting’ the United States (bin Laden, 2004). According to a Watson Institute report, since 2001 it has cost the taxpayers over $6.4 trillion (Watson Institute, 2020). The ‘war on terror’ certainly did not ‘bankrupt’ the American government, although statistics may prove that bin Laden did in fact achieve a great success.

The US struggle against terrorism exceeded American territory, resulting in increasing involvement in countries such as Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom), Yemen (multiple military strikes) or Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom). According to a report released by Neta C. Crawford of the Watson Institute (2018) an estimated of between 480,000 and 507,000 people have been killed in the post-9/11 wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan and over 500,000 people died in the Syrian War. Those numbers are however most likely a significant undercount, as it is difficult to track death toll considering for instance bodies that have not been recovered or ‘indirect deaths’ (such as those due to long term lack of water, food etc) (Crawford, 2018). On top of that, the US-led wars have caused millions to flee the war zones their homes have become, seeking refuge in other countries.

Research shows, that the overwhelming majority of deaths from terrorism around the world is centred in the Middle East, Africa and South Asia – in 2017 95 per cent of terrorism-caused deaths occurred there, whereas deaths in Europe, the Americas and Oceania were less than 2 per cent (Ritchie et al., 2019) Most terrorism occurs in countries with high levels of internal conflicts, for instance Iraq and Syria combined accounted for almost 80 per cent of terrorism-caused deaths in the region and one-in-three globally (Ritchie et al., 2019). One might relatively easy draw a line, connecting this issue with US involvement in internal conflicts, or even directly causing them – this is however an issue for a separate analysis. Although the overwhelming majority of terrorist attacks occurs in the Middle East, Africa and South Asia, and the average deaths in for instance America, over the period 1996 to 2017 ranges around 0.006 per cent (with the exception of 2001 when less than 0.01 per cent of the deaths resulted from terrorism) half of the US population is worried about them or a family member becoming a victim of terrorism (Ritchie et al, 2019). Understandably, the concerns were spiking after major attacks in Western industrialised countries which got an extensive media coverage. However, even in 2001, the number of deaths due to terrorism was significantly lower than for instance car-related accidents, gun crimes or suicides (Jackson, 2005, p. 157). In the aftermath of the attacks, the Department of Homeland Security has been created in order to coordinate anti-terrorism efforts. Three days after the attack, the American Congress passed the Authorisation for Use of Military Force (AUMF), which granted the President the authority to use all “necessary and appropriate force” to anybody who could be suspected of having any connections to terrorist operations (AUMF, 2001). A little while after, the USA Patriot Act has been signed, further strengthening the powers of the federal government.

According to Runciman (2006, p.11) the events of September 11 provided the Bush administration with a “convenient prop on which to hang a set of military and ideological objectives that had been identified well in advance”. The ‘window of opportunity’ appeared, and the US government did not hesitate to use terrorism as an exemplary existential threat which oughts to be combated by any means. The national crisis provided citizens with an emotional and physical distraction, making them more likely to turn a blind eye (or often go through the nearest future with their eyes completely closed) to actions of the government which they normally would not accept. The issue which might be quite important to look into here, is whether throughout the years terrorism really was a threat as serious as it has been portrayed. It can be argued that although it certainly has created a great amount of suffering and has caused unbelievable anguish to those directly affected by it, ‘war on terror’ was not an appropriate was to address terrorism.

Creating Discourses

According to Adam Hodges (2011, Introduction) the truth is “not simply an object external to social interaction; but rather, a form of knowledge emergent from that interaction”. Any event, although it actually does happen, does not however intrinsically contain its own interpretation. The interpretation, conducted by the means of language provides the public with protagonists, motivations and explanations, thus creating a certain narrative which contains very powerful set of assumptions. For the purpose of this essay, the argument shall be largely based on Foucault’s understanding of the term discourse, referring not only to the sociolinguistic analysis of situated use of language, but also to discourse as a “way of representing the knowledge about […] a particular topic at a particular historical moment” (Hall 1997, p. 44; Brown and Yule, 1983). James Paul Gee (1996, 2005) differentiates two notions of discourse, labelling them as ‘little d’ discourse and ‘big D’ discourse. The ‘little d’ discourse relates to the linguistic understanding of discourse, whereas the ‘big D’ discourse to the forms of cultural knowledge bound in specific language use (Gee, 1996, 2005; Hodges, 2011). The latter constitutes what is the Faulcauldian understanding of discourse, which moreover not only refers to objects of knowledge, but goes as far as constituting them (Hodges, 2011, Introduction).

According to Jackson (2005), through analysing public political discourse one might expose certain power relations, a hierarchy of different forms of knowledge and ways through which power practices are legitimised and normalised. The use of language always represents some ideological perspective, it is never neutral. In Jackson’s (2005, p.148) words, “Political discourses […] have a reality-making effect” acting as “constructions of meaning that contribute to the production, reproduction, and transformation of relations of domination in society”. It can be argued thus that only with the help of this deliberately and carefully planned discourse was ‘war on terror’ possible as it normalised counter-terrorism practices and legitimised extraordinary use of force.

The Copenhagen School and Security

The theory of securitisation on which the argument of this essay shall be largely based, has been developed by a group of scholars such as Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver and other collaborators, whose collective work is referred to as the ‘Copenhagen School’. The theory arose as a product of a compromise between the orthodox realist understanding of the concept of security, which pays the utmost focus to the phenomenon of war, and the postmodernist widening conceptions of security as a historical and social construct (Romaniuk and Webb, 2015; Vultee, 2010; Williams, 2003). The debate over the nature of security shifts towards the constructivist theories of International Relations, treating ‘security’ as the outcome of a specific process, rather than an objective condition (Williams, 2003, p 513). This process of securitisation of an issue can thus be defined as successfully casting an issue as an extraordinary existential threat, which calls for the suspension of normal political functions (Vultee, 2010; Wæver, 1995, p.55). The construction of a security issue as an ‘existential threat’ is then analysed by looking into ‘securitising speech-acts’ which according to the Copenhagen School define and create threats (Williams, 2003, p 513). Those speech-acts are then a fundamental part of creating a broader discourse which defines a certain social reality.

Securitising Global Terrorism

After the events of 9/11 the United States’ Homeland Security expenditures have increased significantly. As John Mueller and Mark G. Stewart (2011, Table I.1) explain, by 2011 the expenditures on domestic Homeland Security have increased by almost $360 billion since 2001. Additionally, the expenditures of federal national intelligence with a main goal of defeating global terrorism both within the territory of the United States and abroad increased by $110 billion, while state, local, and private-sector expenditures have gone up around $220 billion more (Mueller and Stewart, 2011, Introduction). The emergence of, what John Mueller (2006) calls, an entire ‘terrorism industry’: consultants, counter-terrorism experts and pundits, can be associated with sustaining the permanent war economy. According to Thomas K. Duncan and Christopher J. Coyne (2011; 2013) starting with World War II the United States’ government retains the character of a war economy even in times of peace. The second half of the 20th century, largely marked by the bipolar world order and constant competition between two superpowers, provided the United States with a long-standing enemy – USSR – politically, economically and above all existentially threatening the country. According to Buzan (2006, p1101) the fall of the Soviet Union created a threat deficit on the part of the United States, to which “[t]he terrorist attacks of 9/11 offered a solution” providing a “long-term cure for Washington’s threat deficit”.

The events of 9/11 were quickly labelled as ‘acts of war’ to which the common sense way to respond was with a ‘war on terror’. It was not however a war on a specific organisation, and although al-Qaeda was the organisation most commonly associated with it, it was a war on virtually anybody that could be related to using terror tactics, what according to Romaniuk and Webb (2015, p 222) gave the American government “a carte blanche to involve American security forces around the globe in counterterrorism (CT) and counterinsurgency (COIN) operations”. On 20 September 2001, just a few days after the attacks, George Bush (2001) said “Our war on terror begins with al-Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated”. Given the construction of terrorism as an existential threat to the security, the functioning and the very existence of Western democracies, the ‘war on terror’ became represented as the only possibility to effectively respond it. It emerged as the only way to properly deal with global terrorism, creating a ‘micro-framework’ within which a different scenario did not exist and even the criticism of the war has been conducted within the war framework (Vultee, 2010, p36). Identifying the opponent as terrorist, delegitimises their political goals, leaving no room for contestations over whether the state’s reaction is in fact legitimate (Vultee, 2010, p 36). Having securitised the threat of global terrorism, the use of overwhelming force in the name of freedom, democracy and liberal values has been legitimised, and the American interests have been framed as universal principles (Buzan 2006; Romaniuk and Webb, 2015). Romaniuk and Webb (2015, p. 223) identified the extraordinary measures as for instance: the military campaign and long-term presence in Iraq and Afghanistan; human rights violations, including torture and extreme forms of interrogation; reduction of civil liberties (phone-tapping, excessive surveillance, acceptance of excessive collateral damage in order to meet the objectives of the ‘war on terror’); targeted killing operations. The logics of exceptionality have convinced a significant part of the public to formally accept such actions as the only effective way to deal with transnational terrorism, leaving very little room for objections as to whether it was in fact a proportionate way to deal with it. It is however only once the mainstream public accepts it when a threat is successfully securitised. The following chapter will intend to demonstrate that in order to do so, the US administration has conducted a careful strategy of creating a broader cultural narrative to what has been happening.

The ‘War on Terror’ Narrative

An aspect very important to the process of securitisation, is that for an issue to be successfully securitised, the securitising actor must hold a great deal of power and therewith the capability to socially and politically construct a threat (Vultee, 2010, p34). In order to get a good grasp of this process, it may be quite useful to come back to the Faucauldian concept of interdependence between power and knowledge, and his understanding of ‘big D’ Discourse. According to Richard Jackson (2005) the language of the ‘war on terror’ has been deliberately constructed to present it as the only reasonable, responsible and inherently ‘good’ response to terrorism. It provided the ‘official story’, accumulating into a broad cultural narrative. Thus, for instance the events of 9/11 become ‘acts of war’ that launched a ‘war on terror’ (Hodges, 2011). The Narrative, situated within the genre or war, by establishing shared meanings constructs the social reality of a ‘nation at war’ which naturalises certain cultural understanding of terrorism, and what ought to be done with it (Hodges, 2011, Chapter 2).

Richard Jackson (2005, p.149) distinguished four elements of the process of creating the narrative of the ‘war on terrorism’: 1. Discursive construction of the events of 9/11, 2. Re-affirmation of new identities, 3. Construction of the threat of terrorism as an existential threat to Western Democracies, 4. Legitimisation of the concept of ‘good war’. Firstly, in order to create a general social discourse of terrorism a sense of communal victimhood has been awoken. The attacks of 9/11 became represented within a war narrative, rather than criminal justice-based narrative giving it a sensation of a supreme emergency justifying the extraordinary solutions to it. It has been put into the context of ‘clash of civilisations’ giving it a symbolic meaning of the eternal struggle of the ‘barbarians’ with the ‘civilised’. The West thus only exists in contract with the ‘Oriental’ Other what in Said’s terms creates an ever-lasting division between ‘us’ and ‘them’ (Said, 1978). The perception of a political identity is thus based on the identification of an enemy, relating to the second element of Jackson’s analysis. The ‘us’ and ‘them’ are given certain inherent characteristics which make them do what they do. Clear divisions between ‘good’,’civilised’ ‘us’ and ‘evil’,‘barbaric’ ‘them’ serve as a powerful demagogic act of decontextualisation and dehistoricisation of terrorists’ actions, presented as lacking any political context and dehumanised. American people however are contrasted with ‘them’ as kind, loving, brave and heroic. The myth of ‘heroic Americans’ versus ‘cowardly terrorists’, is moreover strongly enforced in the popular culture. Thirdly, the events of 9/11 mark a beginning of a whole new ‘age of terrorism’. The ‘war on terror’ becomes a public display of military power, a struggle against the ‘threat to civilisation’, to ‘the very essence of what you do’ or ‘to our way of life’, providing the US government with a discourse of threat and danger. Finally, it is commonly represented within a meta-narrative of a ‘good war’ along with WWII or the Cold War. Counter-terrorism operations turn into a divinely sanctioned war. By bringing justice to the perpetrators, America by definition has God on its side what legitimises its actions.

This deliberately constructed Narrative leaves no questions for the mainstream public regarding the justness and validity of this ‘inherently Just War’. The specific language use creates and establishes cultural knowledge, providing the public with a notion of exceptionality and supremacy of the American culture which circumstantiated occasional use of force due to its supposedly inherently good intentions.

Conclusion

The ‘War on terror’ certainly is between the most broadly contested and discussed issues in the 21st century. It has had a deep influence on politics, society, international relations, popular culture and many more. Although the atrocity of terrorism is undeniable, this essay argued, that the way it has been dealt with was not proportionate. ‘War on terror’ provided means of securitising global terrorism as an existential threat which had to be combated by any means necessary. Bush’s administration discourse, representing the events of 9/11 within the genre of war, rather than of crime, allowed the securitisation of terrorism as a ‘threat to civilisation’, giving the American government almost total freedom in dealing with it, as it became a ‘supreme emergency’. Throughout the essay, the arguments have been elucidated in line with the theory of securitisation developed by scholars of the Copenhagen School, as well as an analysis of the common discourse regarding the narrative of the ‘war on terror’. It came to the conclusion, that the threat of global terrorism has been securitised through microlevel discursive actions creating an official, dominant frame of the state of affairs, which legitimised extraordinary use of force during the ‘war on terror’. The ideological hegemony, aided by its often almost frivolous, propaganda-like reproduction in popular culture and mainstream media, places the discussion about its proportionateness within the war framework. In Jackson’s words (2005, pp. 164-165) “The language powerfully combines World War II, Civilization Versus Barbarism, Good Versus Evil, and Just War narratives into a new super-narrative—a textual symphony—that legitimizes and normalizes the practice of American domestic and foreign policy.” One might draw a line between such super-narrative and the logics of exceptionality marking American policy, which as this essay intended to demonstrate, should be treated with a certain dose of wariness. Failing to acknowledge the context of terrorism and the reasons behind it, the search for more effective solutions becomes practically impossible. By attributing it to pure ‘evilness’ one negates the real motivations and aims of the terrorists. One must not forget about the right to question the world and challenge what seems to be ‘natural’ in order to always reach towards possibly best solutions.

Bibliography

AUMF (2001) S.J.Res. 23 (107th): Authorization for Use of Military Force. Available from: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/107/sjres23/text [Accessed 16/06/2020]

bin Laden, O. (2002) Full text: bin Laden’s ‘letter to America’ [Online] The Guardian Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/nov/24/theobserver [Accessed 16/06/2020]

bin Laden, O. (2004) Full transcript of bin Ladin’s speech [Online] Al Jazeera Available from: https://www.aljazeera.com/archive/2004/11/200849163336457223.html?xif=%20online%20here [Accessed 16/06/2020]

Bonafede, M.,C. (2002) Here, There, and Everywhere: Assessing the Proportionality Doctrine and U.S. Uses of Force in Response to Terrorism after the September 11 Attacks, 88 Cornell L. Rev. 155

Brown, G., Yule, G. (1983) Discourse Analysis. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Bush, G. (2001) Transcript of President Bush’s address. 20 September 2001 Available here: http://edition.cnn.com/2001/US/09/20/gen.bush.transcript/ [Accessed 15/06/2020]

Buzan, B (2006) Will the ‘Global War on Terrorism’ be the New Cold War? International Affairs, 82(6) pp 1101-18

Crawford, N., C. (2018) Human Cost of the Post-9/11 Wars: Lethality and the Need for Transparency. Costs of War. Watson Institute. Brown University

Duncan, T., K., Coyne, Ch., J. (2011) The Overlooked Costs of the Permanent War Economy: A Market Process Approach. George Mason University. Department of Economics

Duncan, T., K., Coyne, Ch., J. (2013) The Origins of the Permanent War Economy. The Independent Review 18(2) pp. 219-240

Gee, J. P. (1996) Social Linguistics and Literacies.: Ideology in Discourse (2nd ed.). London: Taylor and Francis.

Gee, J., P. (2005) An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. New York: Routledge.

Gokay, B., Walker, R., B., J (2003) 11 September 2001: War, Terror and Judgement. Taylor & Francis Group, London.

Jackson, R. (2005) Security, Democracy, and the Rhetoric of Counter-Terrorism. Democracy and Security. 1(2) pp.147-171

Hall, S. (1997) The Work of Representation. In Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, Stuart Hall (ed.), 13–74. London, Sage.

Hodges, A. (2011) The “War on Terror” Narrative: Discourse and Intertextuality in the Construction and Contestation of Sociopolitical Reality. Oxford University Press, New York;Oxford

Klein, N. (2007) The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. Toronto, Alfred A. Knopf Canada.

Morgan, M., J. (2009) The Impact of 9/11 on Politics and War: The Day that Changed Everything? Palgrave Macmillan

Mueller, J. (2006) Overblown: How Politicians and the Terrorism Industry Inflate National Security Threats, and Why We Believe Them. New York, Free Press

Mueller, J., Stewart, M. G. (2011) Terror, Security, and Money: Balancing the Risks, Benefits, and Costs of Homeland Security.Oxford University Press, New York.

Ritchie, H., Hasell, J., Appel, C., Roser, M. (2019) Terrorism. [Online] Our World in Data. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/terrorism#which-regions-experience-the-most-terrorism [Accessed 17/06/2020]

Romaniuk, S. N., Webb, S. T. (2015) Extraordinary Measures: Drone Warfare, Securitization, and the “War on Terror”. Slovak Journal of Political Science, 15 (3) pp 221- 245

Runciman, D. (2006) The Politics of Good Intentions: History, Fear and Hypocrisy in the New World Order. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Said, E. (1978) Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books

Suganami, H. (2003) Reflections on 11 September. In 11 September 2001: War, Terror and Judgement. Edited by Gokay, B., Walker, R., B., J (2003) pp. 3-12 Taylor & Francis Group, London.

Vultee, F. (2010) Securitisation. A New Approach to the Framing of the War on Terror” Journalism Practice, 4(1) pp 33-47

Watson Institute (2020) Summary of War Spending, in Billions of Current Dollars. Costs of War. Watson Institute [Online] Available from: https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/figures/2019/budgetary-costs-post-911-wars-through-fy2020-64-trillion [Accessed 18/06/2020]

Wæver, O. (1995) Securitization and Desecuritization. In On Security, edited by R. Lipschutz, pp. 46–86. New York: Columbia University Press

Williams, M. C. (2003) Words, Images, Enemies: Securitization and International Politics. International Studies Quarterly, 47, pp 511-531

Written at: Technische Universität Dresden

Written for: Stefan Schmitt

Date written: June 2020

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Meaning of US Drone Warfare in the War on Terror

- ‘Illegal Criminals Invading’: Securitising Asylum-Seekers in Australia and the US

- From 9/11 to Humanise Palestine: Investigating the Terror of Grievability

- The Spread of Islamic Terror in the Contemporary World

- Incubators of Terror: Anatomising the Determinants of Domestic Terrorism

- Fighting over War: Change and Continuity in the Nature and Character of War