This is an excerpt from Varieties of European Subsidiarity: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Get your free download from E-International Relations.

While Canada’s historical evolution from a centralised nation state in 1867 to a decentralised one can be viewed as unique, the country shares a common dilemma with other nation states, and federations, in particular. Decisions need to be made over how decision-making authority will be divided between multiple levels of government. There is no single global solution for the division and jurisdiction of powers within a nation state or multi-level government structure (Friesen 2003). Some have opted for a more centralised structure while others favour greater decentralisation. In this context, the principle of subsidiarity can provide guidance. This principle holds generally that decision-making authority should be held as close to the constituents affected by the decision as possible while higher levels of authority should hold a subsidiarity role; delegation of authority essentially moves from the lower level upwards when a case can be made that the issue to be decided upon is of a common character, affecting more than one of the members, or could not be dealt with adequately at the lower level. Examples of each, respectively, could be common defence, trans-boundary water rights for a river across members’ territories, or a response to a natural disaster.

While in Canada’s case, subsidiarity is not formally declared in the Constitution of 1982 or the British North America Act (BNA) of 1867, it has arisen directly and indirectly through Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) decisions through modern cases involving disputes over the division of powers (Kong 2015). This is in contrast to the EU case, where the principle has been more formally adopted in treaties (Broullet 2011). It has, however, also arisen specifically over fiscal issues, namely different governance level’s ability to tax and spend. The argument here is that subsidiarity alone would not be enough to genuinely provide meaning and substance over the distribution of powers without the fiscal dimension being addressed. The principle of subsidiarity, in other words, is less meaningful, if a level of government does not have adequate revenue sources to act in its area of jurisdiction. The fiscal division of powers plays a vital role for this principal since it would essentially be violated if taxation and revenue raising powers did not match the remaining division of powers, in scope and intent.

This chapter has two core objectives. The first is to provide for the reader that is more familiar with the EU than with Canada some general characteristics that may be useful in understanding why Canada is likely to function more effectively and efficiently as a decentralised federation as opposed to a highly centralised nation state (Follesdal and Muñiz Fraticelli 2015, 90-1). On the one hand, considerable scope for autonomy exists at the provincial and territorial level, while on the other there is reason and interest for the thirteen members to see value in being together in a federation as opposed to separate nation states; despite the wide diversity in the population sizes of the Canadian provinces and territories, economic interests, and tensions over other areas such as language. The second objective is to examine the fiscal division of powers, notably over the powers to tax and spend.

Subsidiarity and fiscal decentralisation

The choice a multi-level government has over its structure can essentially be reduced to two sets of related questions. The first is the decision over which levels of government within the nation state should have jurisdiction over which areas. Should schools, healthcare, defence, infrastructure, education and language be held at the national, provincial/territorial, or municipal level of government? The second set of questions has to do with which level of government has ultimate power or authority over this set of decisions. Which level gets to decide in the end whether the jurisdiction is supposed to be at the local, provincial or national level? The nation-state may be viewed as being comprised of lower-level units which hold authority, for example, and delegate power upwards on a case-by-case basis. The reverse may also be true where the national level of government is deemed to hold the power to decide to delegate powers and jurisdiction downwards.

The principle of subsidiarity provides guidance not only over this division of powers, but also over how the decision over the division should take place. In its simplest form, this principle holds generally that decision-making authority should be held as close as possible to the people in whose interest the decision is going to be made. This means that the starting point is the local level with authority or jurisdiction being delegated upwards when a case can be made that the decision affects a wider group of people, or there are efficient and effective reasons to do so, such as responses to natural disasters. In these extreme situations the local level may not be able to respond. It follows from this principle further that the national level would essentially receive its reason for existing based on consent from below and it would play a subsidiary role, acting in those areas of common interest across the lower levels of government (Halberstam 2009).

The principle of subsidiarity can also be interpreted as providing guidance over the division of powers in a multi-level government structure in other essential ways. For instance, it also follows from this principle that the nation state is essentially the sum of its parts because it has derived its authority from the lower levels and not the reverse (Friesen 2003). This means that the nation-state itself is only legitimate so long as it is held as legitimate by the lower levels of government. In the case of a federation, it would be legitimate only in so far as the members of the federation viewed it as legitimate. The national level exists to serve the common interests of the members and cannot pursue policy, legislation or other activities that hinder or harm the lower levels.

Further, with powers and jurisdiction divided according to this principle, there are positive and negative aspects of subsidiarity (Cyr 2014). In particular, the principle outlines and protects the lower levels from infringement into areas specified as within their jurisdiction. This is the negative dimension in that it prevents the national level from undue interference. However, there is also a positive dimension in that the national level is expected to act, potentially interfering, in some situations for the benefit of citizens residing there, such as through providing assistance. This can be justified in cases where the lower level is unable to act effectively or efficiently. This could take place during an invasion, natural disaster, or perhaps even poor economic times where insufficient revenues may mean that citizens suffer. The idea that the higher level can step in provides substance and reason for being a member, after all, of the nation. Other cases may include when a decision by a lower level of government affects another region, such as regulating river flows or dams.

Modern interpretations of the principle of subsidiarity, beyond this element of strict division of conditions when one level could act in another, also stress the cooperative nature of the principle (Hueglin 2013). The different levels of government, therefore, according to subsidiarity are not meant to compete so much as complement each other. Citizens of a region of the country are both local and national citizens. It would not make sense for the federal level of government to pursue a policy that hinders lower levels of government from serving their own constituents. This is due to the fact that citizens in that polity are both local and national, and it would follow that the national level of government would be harming, not serving, some of its citizens. Further, a local level of government would not be permitted to harm other members of the country through its policies since that citizen is also a member of the whole, and reciprocity would dictate that it would be harmful to the whole if all the members sought such harmful courses of action against each other. Further, despite clear boundaries over jurisdiction, subsidiarity does hold that the higher level can intervene to provide assistance. Thus, rather than viewing the levels as distinct and acting within specified areas of jurisdiction, the principle also validates a cooperative role and argues against policies within the nation that seek to harm the ability of other levels, or citizens in another constituency.

While this principle provides guidance in making the core decisions over the division of powers and establishes some boundaries over behaviour between the levels, it can also be viewed as an efficient principle. Subsidiarity allows for multiple, legitimate majorities to exist within a nation due to the way powers are divided (Cyr 2014). If the central, national level of government held all decision-making power, or had the authority to impose its will across the nation, there would be some issues over which some sub-national levels would be satisfied while others would not. Perhaps a majority was achieved at the national level on some issue, such as the language of instruction, for instance. All schools in the country would then have to comply and adopt that language due to the will of the national majority, even if there was a single small region where few, if anyone, spoke that language. It could be held that satisfying the majority is sufficient. However, if language laws were decided at the sub-national level, all those regions who supported the national language would continue to do so at the local level and they would be at least no worse off. However, the smaller region with the other language would now be better off than before. In this case, more people would be satisfied in the nation with language policy if it were allocated to the sub-national, as opposed to the national level. Subsidiarity, because it favours policy decisions as close to the polity affected as possible, is more likely to result in greater satisfaction for greater numbers of people than if all the decisions were at the national level; it thus maximises social welfare which may or may not be consistent with a strict majority vote ruling. Due to dividing decision-making power the way it does, subsidiarity can be argued to be aligned with the ‘greatest happiness principle’ since it allows for multiple and legitimate majorities to take place within a nation state (Bentham 1988).

While many of these dimensions of subsidiarity have been adequately explored and helped prepare the way for understanding, one dimension typically left out is the division of fiscal powers. This fiscal dimension of subsidiarity is also crucial, if not of vital importance. If a lower level, such as a province, has specific powers, such as over health, education, local infrastructure, in line with the principle of subsidiarity, that a province is essentially entitled to pursue policies and activities in those areas that best reflect the interests, preferences, and priorities of its constituents. If the power to raise sufficient revenues to cover the costs involved in the provision of these areas is not also at this level, however, the province will find itself less free to pursue the areas within its jurisdiction as it sees fit. This could take place if the province had to rely on conditional transfers from another level of government to finance the decisions it makes within areas of its legitimate jurisdiction.

This dilemma can be seen more clearly by considering the case of a federation where the vast majority of public goods and services are provided at the regional (province, state or territory) level. However, all taxes are collected under the authority of the national government and then transferred to the provinces through some funding formula or with conditions attached. This would mean that the federal government, subject to majority rule at the national level, could in the end dictate to the lower level that they would only receive funds if they made decisions in line with what the majority of the country dictated. The federal level could withhold educational funds unless the lower level adopted, for example, the same language of instruction as the other provinces, territories or states. Thus, despite the fact that the province might have the legal authority to choose another language, or policy reflective of its interests, priorities and preferences, it would in effect be limited to going along with the will of the higher level of government which has the ability to withhold funding. This would render the lower level less able to pursue and use its legal authorities within areas under its jurisdiction.

It does not hold, however, that therefore all taxes should be collected at the lowest level possible and transferred upwards. This would also violate the division of powers. The example of national defence demonstrates the problem with financing from the bottom up. If all taxes were collected at the municipal level and transferred upwards, the municipalities could also hold the federal level hostage and prevent the federal level from delivering and acting in areas where it is expected and efficient to act. If an invasion took place on one side of the country, it would be cumbersome for the federal government to have to request from all the lower levels additional sufficient funding to defeat an invasion. Further, many municipalities, especially those further away from hostilities, might decide that the burden ought to rest with those closest to the conflict and transfer too little upwards in time. If they had the power to tax and decide to transfer, the entire nation would be potentially threatened by expansion of foreign invasion, and by the time the municipalities far away realised it was in their interest to pay more, it would be too late.

As a result, it is argued here that parallel to the discussion on the division of powers across multiple levels of government, the fiscal dimension, revenue raising and spending, must follow this principle. Adequate resources for financing decisions within the jurisdiction of the level of government must be allocated in line with subsidiarity. If a level of government does not have sufficient revenues, it will have to rely on another level of government for finances, and this would in effect violate the very dilemma that the principle of subsidiarity sought to resolve and avoid as far as possible. It also means that in those cases where a level of government is unable to serve its citizens, the national level has greater clarity in terms of providing assistance in addition to the possibility of unconditional and conditional grants to pursue issues of national concern.

To be sure, the principle of subsidiarity will not remove all controversy or disputes over areas of jurisdiction and financing. It will serve to reduce those disputes, however, especially in large diverse countries with multiple levels of governance. Evidence from Canada will help to show that despite being initially designed as a centralised power, there is sufficient diversity that likely explains the decentralised nature of modern Canada and the rationale for adopting the principle of subsidiarity. Further, data shows significant decentralisation of revenues across the country that matches spending, with areas of transfers and co-financing. In many aspects, Canada has embraced the cooperative nature of subsidiarity, the fiscal dimension, yet with significant tax and spending at the national level to pursue common interests.

Fiscal subsidiarity in Canada

According to the preamble of the BNA, the provinces of Canada (Ontario and Quebec), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, expressed their ‘desire to become federally united into one Dominion under the Crown of Great Britain and Ireland, with a Constitution similar in principle to that of the United Kingdom’ (British North America Act 1867). Among many reasons for forming this union were the raising of public credit, transportation and defence (Magnet 1978). At that time the former British colonies to the south had already declared independence nearly a century before and had recently concluded a bloody civil war. The remaining British colonies to the north had a scattered, largely rural, population of only 3.5 million with considerable concern over defence since their southern neighbours were beginning to expand westward and northward at a time when Britain did not want to become involved in additional war efforts to defend its remaining claims in North America. The formation of the Dominion government was thought to offer a viable solution to a common set of problems in terms of collective defence, the raising of sufficient funds for transportation and infrastructure to foster growth and development, and an internal common market (Norrie and Owram 1996; Pomfret 1981).

Beyond the BNA outlining a parliamentary system of government, it also divided legislative powers between the new federal government and the provinces. There was, at that time, considerable dispute over transferring power to the new government and a compromise was reached that favoured a strong central government with considerable economic power remaining in the hands of the provinces. In the sixth section of the Act, for example, Article 91 grants the national level with legislative authority over all matters related to peace, order and good government that do not exclusively fall within a list of specific powers granted to the provinces. Article 91 further lists 29 specific issues over which the national government has authority including matters such as defence, weights and measures, navigation and shipping, currency, banking and naturalisation, and ends by granting any residual matters not specifically outlined in the BNA at the time of writing to the national level.

Article 92 outlines the matters falling within provincial jurisdiction which were at that time thought to be less important; the growth of the social welfare state had not yet taken place. This article specifies 16 specific powers followed by additional articles over education (Article 95) and agriculture (Article 93). Most of the enumerated powers were thought to be of a more local nature, such as hospitals, justice administration, and control over municipalities. Further, while the provinces were limited to areas of direct taxation, the federal level had the power to raise funds by any mode or system of taxation, including over customs and excise taxes (Article 122). This latter tax was one of the main sources of government revenue at the time and even during the initial years of the new country, provinces received nearly half of their revenues from the federal government (Magnet 1978).

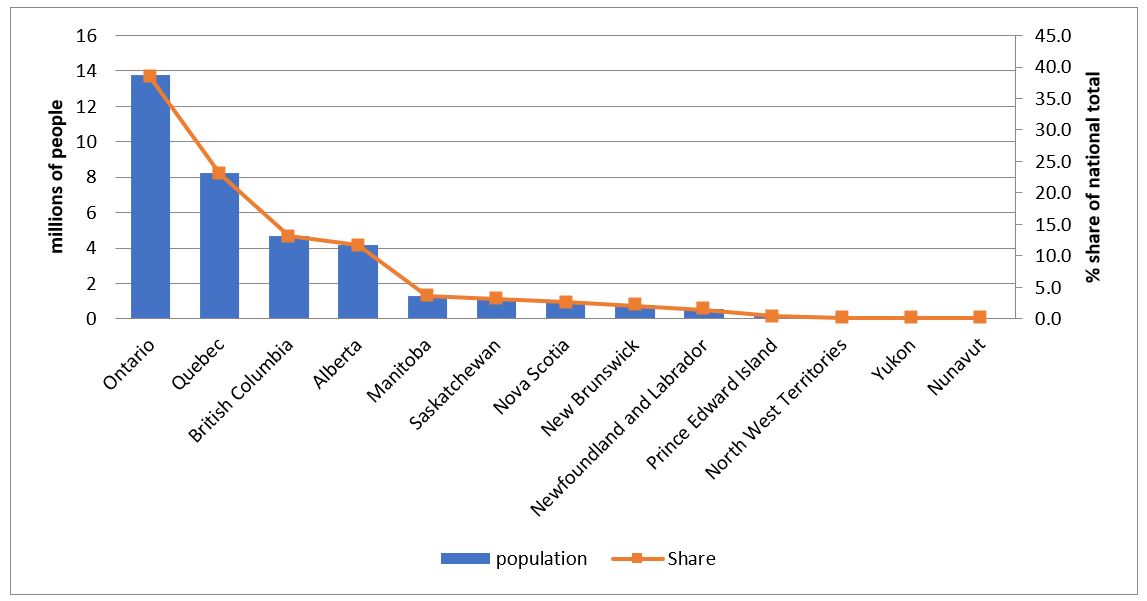

Canada today, however, stands in stark contrast to these original intentions and designs in 1867. It can be characterised as largely decentralised with considerably more room for tax and spending at the provincial and municipal levels combined than at the federal level (Simeon and Papillon 2006). Further, the country has grown to 36 million people with ten provinces and three territories. Figure 1 shows Canada’s population by number and percentage share across the provinces and territories and can help shed light on one of the key challenges the federation faces.

There are several critical observations that can be made from this figure with respect to federalism. First, of the 13 members of the federation, four provinces are large in terms of population while the remaining are small by comparison. In fact, the largest province, Ontario, has nearly 40 per cent of the nation’s population and together with the second largest, Quebec, 61.5 per cent. The four largest provinces together have 86.3 per cent of the national population. The rest of the people reside in the remaining six provinces and three territories. In fact, these smaller nine members of the federation have far less than 10 per cent each of the national total.

The distribution of Canada’s population across the provinces and territories poses a significant challenge to the governance of the federation. This can be seen more clearly if one were to imagine Canada as a highly centralised country where most decisions were to be made at the national level rather than at lower levels (provincial/territorial, municipal) across the country. If a policy, piece of legislation, or spending proposal satisfied the two largest provinces, or perhaps even all four of the largest together, they could form a majority, democratically, and dominate the national agenda. Even if the remaining nine provinces and territories significantly disagreed or sought a priority that was only in their interests. Even collectively they would not be able to achieve their objectives through a simple majority rule. If Canada, as a nation state, were organised in a centralised fashion, many of the members of the country would find it difficult to find a benefit in remaining within the country when it comes to policy disagreements.

It may be the case, however, that many across the country share much in common. There may even be agreement in many areas, meaning that disputes would be not so common and perhaps majorities of smaller members might be aligned with the larger ones. In a country with such diversity in terms of economic priorities, local infrastructure projects, or the level of prosperity, decentralisation over decision-making would, however, allow for multiple legitimate majorities (Cyr 2014). By having a division of powers between the federal government and provinces and territories, the nation as a whole can avoid dominance by the larger members and allow for divergences in preferences, priorities and views that can accommodate and avoid disputes from arising in those cases where interests diverge, and there is no reason for a higher level to impose its will on the lower level.

Incidentally, and secondly, it is also apparent in Figure 1 that the two largest members of the federation are Ontario and Quebec. Together, these two provinces located in the centre of the country have 61.5 per cent of the total national population, with 38.5 and 23 per cent respectively. While Ontario is an anglophone province, Quebec is francophone. On the one hand, the majority of Canada is in English dominated provinces and territories, and it would be hypothetically possible for a simple majority of the Canadian population to impose its will on Quebec if the country were highly centralised, especially in the area of language laws. A majority of Canadians could simply decide and vote to make the country unilingual, if it so desired. On the other hand, voters in Quebec and Ontario, hypothetically, could also vote together to collectively dominate the national agenda and trade votes strategically, including in areas of language laws. The benefit of dividing powers within the federation can be seen from this hypothetical example more clearly. Lower levels of government can pursue language laws, and the nation as a whole can achieve benefit by adopting and enshrining both English and French, even though Quebec has a sizeable portion, yet minority, of the country’s population. Decentralisation allows the members to pursue their own interests, especially where they diverge, yet remain together in a cooperative federal state.

It is also the case that during the past 150 years of Canada’s evolution from a centralised to a decentralised nation, many of the matters that were originally considered minor, such as health and education, have become much more important. These matters happen to also fall under provincial jurisdiction and the growth in expenditures to provide health and education in part explains the growth in level of spending at the provincial levels. This trend helps to explain how in Canada the share of public spending at the federal level has declined since the 19th century. Canada’s federal level of government spends about 35 per cent of the total public spending. This is similar to comparable data from Switzerland (34 per cent) while it is much lower than other states, such as the USA (61 per cent), Australia (53 per cent), and Germany (41 per cent). Thus, Canada appears by comparison to be one of the most decentralised federations by portion of budgetary spending (Simeon and Papillon 2006).

The share of total public spending could be somewhat misleading. It could be that the federal level of government collects the bulk of revenue and then transfers through some mechanism funds to lower levels of government. This takes place to some degree in Canada, but not to the degree that would take place in nation-states where the division of taxation powers is more centralised and exercised at that level. If this were the case in Canada, it would be possible, hypothetically, for the federal level of government to make decisions over the use of public funds at lower levels and impose conditions on receiving revenues. This would, in effect, leave lower levels with less decision-making authority than what might otherwise appear in terms of a constitutional division as stated on paper. For example, the federal level could withhold funding if it thought the lower level was not going to spend it in a way that the national level thought best, such as on a specific set of educational programs. The federal level could state that it would provide funding for vocational schools, colleges and universities to the sub-national level only if the lower level provided specific training in specific areas and in a specific language. Canada could state that it would provide funding to Quebec for higher education, but only if the language of instruction were in English, otherwise the funding would stop or not be provided. This makes the case clearer for why authority over revenue raising also plays a critical role in the distribution of powers in a federal state; without the ability to adequately raise revenue to spend on areas within an authority’s power, it would have potentially less real say in how it exercises its powers to meet local needs, priorities and preferences.

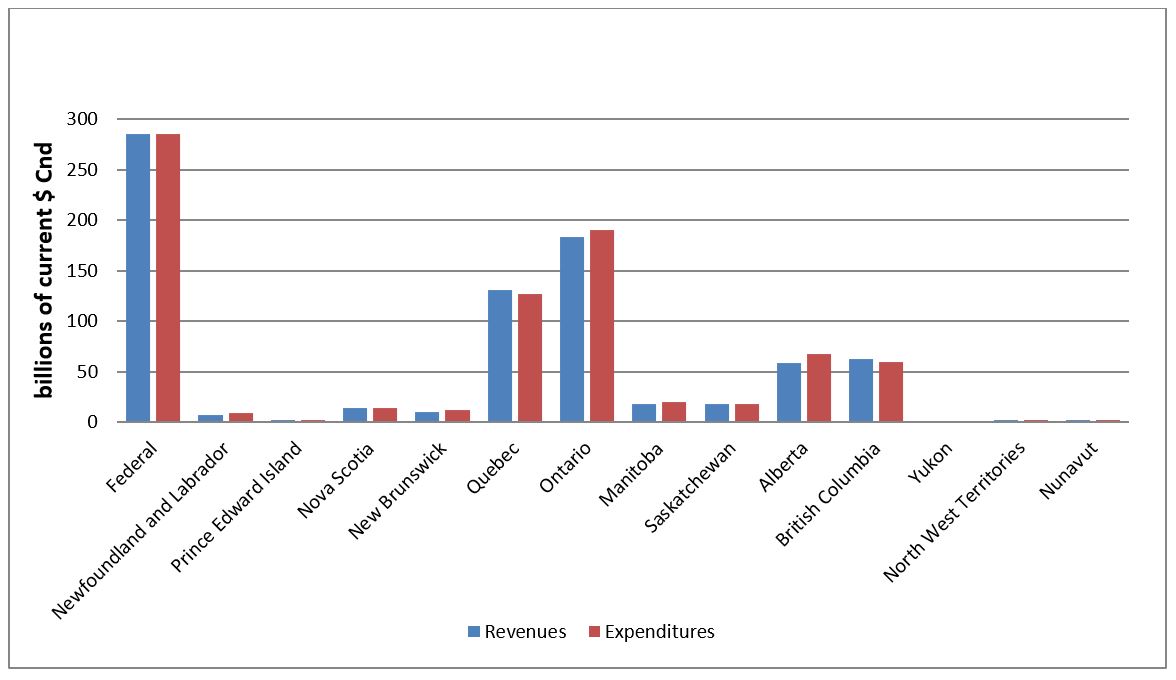

Figure 2 sheds some light on the revenue and expenditures by level of government in Canada’s federation. It shows the total in 2015 of revenues and expenditures by the federal level followed by each of the provinces and territories. Municipal and local level spending are included in the provincial and territorial totals. Although four members are too small to show up comparatively in the figure, namely Prince Edward Island, Yukon, the North West Territories and Nunavut, the overall trends remain similar. In Canada, the two levels of government have revenue bases that are similar to their expenditure level. In fact, Canadian provinces and territories have significant access to fiscal resources to cover the areas over which they exercise authority. This helps prevent the possibility that the significantly larger members could overshadow or dominate how smaller members of the federation use their powers. Second, it is evident from the figure that two provinces, Ontario and Quebec, appear on the national scene as being almost as large as the federal government when compared to the size of the other provinces. Third, it appears that Canada’s federation has not only significant powers at the principle or territorial level, but also a division of fiscal powers that provides a level of adequacy to hold considerable decision-making authority over the powers they have.

At the same time, for areas of common interest across the country, the national level plays a significant role in terms of tax and spending. The federal level has access to own resources to not be left completely dependent on seeking bilateral and multi-lateral deals constantly in order to access revenues and spend as it sees fit. This point is worth emphasising as well when it comes to decentralisation. It is not as if the country is completely decentralised in the hands of lower levels of government. The principle of subsidiarity holds that the higher level is delegated a subsidiary role and that power should remain at the lower level as far as possible. This does not deny that there are areas of national concern, such as national defence, inter-provincial infrastructure projects, or other policy areas that are in the legitimate sphere of power of the national level. Further, it would be cumbersome to relegate the role of the federal level to only engage in Canada at the consent of lower levels. This would mean that two to four large players would dominate the scene, and the federal government would essentially be the government of Ontario, Quebec, and plausibly Alberta and British Columbia. For the federal level to not be dominated by a small number of large members, and to also avoid the cumbersome process of seeking consent over legitimate national issues, it makes sense to have some power at that level. In fact, the federal level also has fiscal authority to raise and spend funds. It oddly has constitutionally the greatest power to tax, but through cooperation, court decisions, and evolution, does not actually play the role originally intended in 1867 today.

Not apparent in Figure 2 are some worthwhile nuances about the federal system in terms of subsidiarity and fiscal relations. Collecting taxes is not free. Tax administration is costly, and it would pose even more burden per capita on smaller members of the federation than on the larger, at least generally speaking. In areas where both the federal and provincial/territorial levels of government tax the same base, having separate tax administrations at both levels would replicate costs and pose an even greater burden on taxpayers across the country. Further, it could be argued that having provinces and territories carry out all taxation and transfer to the federal level might have some negative consequences, such as the larger members having more effective say in the country since they hold larger purse strings. It would also involve arguably more costs than perhaps having a nation-wide collection agency that transfers to the lower levels.

In Canada, although tax powers are divided in the 1867 BNA, with lower levels having less room to tax than the federal level, the federal level provides for the collection of the bulk of taxes collected in the country. The Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) collects personal income tax across the country, for example, with both provinces and the federal level taxing personal income similarly, but with some room for difference across the provinces. The share of provincial tax collected in a specific province is then transferred back. This is an example of subsidiarity potentially providing a basis for cooperative federalism, especially when it is considered that exceptions have also been tolerated. Within this general system, Quebec collects its own share of the personal income tax in that province. For corporate taxation, Alberta, Ontario and Quebec also collect their own portions separately (withheld at source). These nuanced details not only indicate some areas where there are federal-provincial tensions, but also where there is scope for cooperation and agreement to allow for diversity while remaining a nation state as a whole.

Although there is significant room for members of Canada’s federation to tax and spend in areas within its jurisdiction as outlined in the 1867 BNA and the 1982 Constitution, there are areas of national interest and overlap in some program areas. Although there are divisions and tensions, there is considerable room for dual identities. While citizens may view themselves as residents or members of a specific province or territory, and while these identities can remain quite strong even when members of the federation move to another province or territory, they are also citizens of the federation. In areas such as health, education, and other social programs, the provinces and territories would differ to some degree in their ability to raise revenues sufficiently to cover similar levels of these across the country simply because of income inequality and other economic differences, such as stability in regional economies over time.

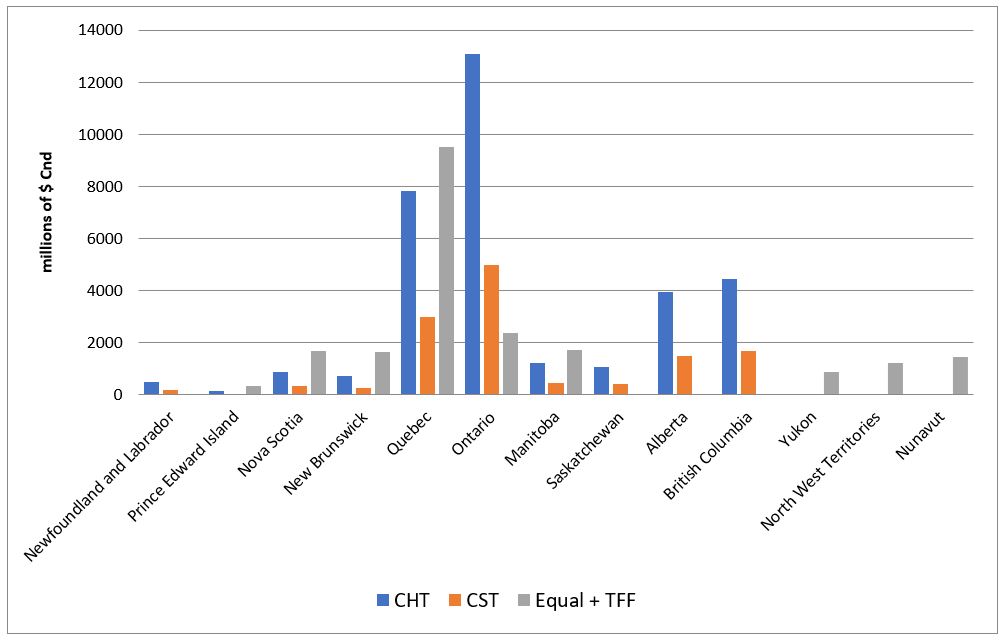

Due to differences in abilities to pay for social programs across the country, the federal level of government has four major transfers they make to provinces and territories: the Canada Health Transfer (CHT), the Canada Social Transfer (CST), equalisation payments to provinces, and a Territorial Financing Formula (TFF). From 2015 to 2016, the total transferred through all four programs from the federal to the sub-national levels was nearly $ Cnd 68 billion. While the first two are for financing specific programs, equalisation and TFF are considered unconditional grants, with the intention overall to ensure that citizens of the federation enjoy similar levels of what are considered critical social programs regardless of the province or territory in which they happen to reside. Without detailing a history of contentions over these sizeable transfers, such as interference into powers that are technically within the scope or jurisdiction of provinces, in terms of the principle of subsidiarity it could be argued that while the bulk of spending and revenue raising takes place at these lower levels, this overlap and transfer also provides citizens with benefits to being members of a federal state and a large common market.

Overlap also would indicate and be in line with modern interpretations of subsidiarity involving cooperative approaches to achieve equity, solidarity, efficiency and effectiveness in program delivery rather than defending strict divisions of powers as may be outlined in constitutional provisions. For example, education is technically within the scope of provincial jurisdiction, yet it might be nationally desirable to ensure that all Canadian citizens, regardless of where they live, have access to similar levels of educational programs, while at the same time recognising that local economies may have sufficient differences in needs, specialisation to permit some degree of diversity in funding, and programming.

Figure 3 provides an overview of the four major transfer programs in Canada for 2015 to 2016. Due to scaling issues, it is difficult to see the levels of all four across all provinces and territories. In that year, Newfoundland and Labrador, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia did not receive equalisation payments, but they did receive CHT and CST transfers. All three territories received TFF, and the remaining received a combination of all three (except TFF).

Thus, while Canada can be characterised as having a highly decentralised federation in terms of the share of public spending at the federal level, there is not only considerable room for lower level raising of revenue to act in areas under their jurisdiction, but also general overlap and cost sharing between the two levels to ensure that there is adequacy in terms of local provision of core public goods and services. Canada’s decentralised federation has characteristics of federal jurisdiction in some areas, provincial or territorial in others; yet overlap in fiscal terms despite clear legislative boundaries outlined in the original BNA of 1867. These fiscal dimensions indicate considerable evolution from the original intent to the reality of today.

Conclusion

The fiscal dimension of subsidiarity can help to understand how Canada can remain together as a highly decentralised federation. It is not arbitrariness, pure historical luck, or a history of ad hoc decisions made on a short-term basis. The country could have been configured, despite the division of powers in 1867, in favour of a strong centralised government that raised the bulk of taxes and found ways to impose its decisions through national majority rule on the provinces and lower levels of government. This would be difficult in a country like Canada due to several key features within the country. There is considerable diversity across the provinces and territories in terms of population, economic interests, culture and preferences. If the country were highly centralised, there would be considerable risk that national decisions would be dominated by a small number, perhaps even just two or three provinces. Economic interests and policy preferences and priorities of the remaining members would be considerably overshadowed with the exception of those few areas where there were coincidentally common views. These key features, when combined with the original division of powers, lends a degree of understanding as to why Canada is decentralised with considerable room for lower levels of government to make decisions that reflect local priorities, preferences and culture.

Further, this evolution of decentralised decision-making and jurisdiction in Canada appears to be consistent with the principle of subsidiarity in the sense that authority is closer to the constituents’ concerns with the federal level playing a subsidiary role. This also appears to be the case in the fiscal dimension since each level has considerable access to resources to act within those areas of its jurisdiction. Subsidiary is less meaningful, and potentially violated, if each level is not provided with the power to raise adequate revenues to cover the expenses involved in carrying out the decisions it has the power and authority to make. Subsidiarity, however, is not explicitly adopted in terms of the original division of powers in the 1867 BNA nor in the Constitution of 1982. In Canada’s case, the principle of subsidiarity has shown up instead directly and indirectly in modern Supreme Court decisions over jurisdictional disputes between the levels of government. Whether by intentional design, custom or habit, Canada has, effectively in these key ways, adopted the principle of subsidiarity lock, stock and barrel.

Figure 1: Canadian population, and share of national total, by province and territory, 2015. Source: Statistics Canada (2015).

Figure 2: Total government revenues and expenditures in Canada by level of government, 2015. Source: Statistics Canada (2015).

Figure 3: Transfers from federal to sub-national levels of government by province and territory, 2015–2016. Source: Government of Canada, Department of Finance (2017).

References

Bentham, J. (1988). The Principles of Morals and Legislation. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books.

British North America Act (1867) 30-31 Vict., c. 3. Available at: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/csj-sjc/constitution/lawreg-loireg/p1t11.html

Broullet, E. (2011). ‘Canadian Federalism and the Principle of Subsidiarity: Should we open Pandora’s box?’. The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference 54 (Article 21): 600–32.

Cyr, H. (2014). ‘Autonomy, Subsidiarity, Solidarity: Foundations of Cooperative Federalism’, Constitutional Forum 23(4): 20–40.

Follesdal, A. and V. M. Muñiz Fraticelli (2015). ‘The Principle of Subsidiarity as a Constitutional Principle in the EU and Canada’. The Ethics Forum 10(2): 89-106. Available at: https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/ateliers/1900-v1-n1-ateliers02386/1035329ar.pdf

Friesen, M. (2003). ‘Subsidiarity and Federalism: An Old Concept with Contemporary Relevance for Political Society’. Federal Governance 1(2): 1–22.

Government of Canada (2017). Federal Transfers to Provinces and Territories 2011-2012 to 2015-16. Department of Finance. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/programs/federal-transfers/major-federal-transfers.html

Halberstam, D. (2009). ‘Federal Powers and the Principle of Subsidiarity’. In V. Amar and M. Tushnet (eds) Global Perspectives on Constitutional Law, 34–47. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hueglin, T. O. (2013). ‘Two (or Three) Tales of Subsidiarity’. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association, June 4–6. Victoria, B.C. Available at: https://www.cpsa-acsp.ca/papers-2013/Hueglin.pdf

Kong, H. L. (2015). ‘Subsidiarity, Republicanism and the Division of Powers in Canada’, Revue de Droit de l’Université de Sherbrooke 45: 13–46.

Magnet, J. E. (1978). ‘The Constitutional Distribution of Taxation Powers in Canada’, Ottawa Law Review 10: 473–534.

Norrie, K. and D. Owram (1996). A History of the Canadian Economy. Toronto, Ontario: Harcourt Brace.

Pomfret, R. (1981). The Economic Development of Canada. Agincourt, Ontario: Methuen.

Statistics Canada (2015). Table 10-10-0017-01. Canadian Government Finance Statistics for the Provincial and Territorial Governments. Available at: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=298948

Statistics Canada (2015). Table 17-10-0005-01. Population Estimates on July 1st, by Age and Sex. Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000501

Simeon, R. and M. Papillon (2006). ‘Canada’. In A. Mujeed, R. L. Watts, D. M. Brown, and J. Kincaid (eds) Distribution of Powers and Responsibilities in Federal Countries, 91-122. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Subsidiarity and European Governance: Export and Investment Promotion Agencies

- Federalism, Functionalism and the EU: The Visions of Mitrany, Monnet and Spinelli

- Subsidiarity: A Principle for Global Trade Governance?

- An Unlikely Alliance? Canada-Japan Relations in the Justin Trudeau Years

- Opinion – Khalistan’s Impact on India-Canada Relations

- Opinion – Poland’s Territorial Defense Forces: A Solution for Revitalizing Canada’s Reservists