Direct communication with social media followers is a relatively new tool for the state to narrate and characterize each use of force. For the purposes of international relations scholarship, the posts provide rich data to uncover the symbolic “mechanics” of how a state sold a violent national security strategy in general and how Israel sold Operation Protective Edge (OPE) to its Anglophone followers in particular. To accomplish this constructivist IR research agenda, in this article, I rely on sociological methods of interpretation. In particular, I analyze English-language social media discourse produced and shared by Israel Defense Forces, the Office of the Prime Minister of Israel, and the Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs just before and during the 2014 operation.

On July 23, 2014, fifteen days into Operation Protective Edge – air strikes and an Israeli ground invasion of Gaza – Lt. Col. (Ret) Avital Leibovich, creator of the Israel Defense Forces’ (IDF) social media unit and director of the American Jewish Committee in Israel at the time of writing, stated during an interview with CNBC that:

Social media is a warzone for us here in Israel. It’s a way to communicate with a large variety of audiences, worldwide, without an editor interfering. Here we can have our own campaigns, we can decide the size of the headline, what that headline will be, exactly which pictures and footage to upload. So it really enables us to reach millions and millions of people who use social media as their sole source of information.

2013–2015 was the peak of production by the IDF and Prime Minister’s Office of hundreds of colorful graphics overlaid by additional text disseminated on social media. When social media posts combine visual imagery with concise text they serve as persuasive vehicles that together carry many political, cultural, and emotional codes. The posts shared during OPE unequivocally legitimate Israel’s use of force and delegitimate Hamas’. This is not at all surprising; one would expect state agents to do this work on any platform. What is significant is how Israeli state agents used specific words and images to link Israel’s values to the West. We must keep in mind that while the association may appear obvious, a great deal of work goes into maintaining it. I ultimately argue that Israel establishes itself, in part through its unmediated social media discourse, as part of the Islamophobic hegemonic coalition that positions Israel as the eastern-most front of the United States’ “global war on terrorism”.

Operation Protective Edge

Operation Protective Edge is but one chapter in the larger narrative of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Following war and dispossession, the state of Israel was established in 1948. 1967 marked the beginning of Israel’s military occupation of Gaza, the West Bank, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai Peninsula. The Palestinian Authority was formed to govern Gaza and areas of the West Bank in 1994, pursuant of the Oslo Accords. In 2005, Israel “disengaged” from Gaza, removing all settlements and soldiers and subsequently the Islamist political organization Hamas was elected to lead Gaza. Israel maintained its occupation of the Palestinian Authority-controlled West Bank and led several military operations against Gaza throughout the ensuing nine years preceding OPE.

Early 2014 had been a period of relative quiet between Israelis and Palestinians characterized by U.S.-brokered peace talks and a mundane Israeli state social media presence that consisted mostly of good wishes from and profiles about soldiers and politicians. A few notable events then dramatically shifted the tenor of Israeli state social media. First, on April 23, 2014, Hamas and the Palestinian Authority announced a government unity pact. The two governments, representing Gaza and the West Bank, respectively, had been at odds over the years, thus this pact constituted a major change in Palestinian political dynamics. Second, in June, three Israeli Jewish teenage settlers were kidnapped and, after a high-stakes manhunt for the perpetrators, were ultimately found murdered near Hebron in the West Bank. Third, there were intermittent rocket fire exchanges between Hamas in Gaza and Israel. These events led to OPE in July. The operation began with airstrikes and evolved into a ground invasion, which, by the end of the operation in late August of the same year, became a targeted mission to eradicate Hamas’s network of tunnels.

Since Operation Protective Edge, structural and physical violence has continued in Gaza. During the 2018-2019 Great March of Return, snipers killed unarmed children, medical professionals, and journalists present at the peaceful protests demanding the rights of the Palestinian diaspora to return to their homeland. A botched raid in November 2018 resulted in the death of 7 Palestinians and Israel engaged in aerial bombings of Gaza once again in March 2019. Additionally, given the ways social media has proliferated and evolved in the last few years it is more important than ever to have an analytic record of the history of a state’s use of such platforms.

The Office of the Prime Minister of Israel, the IDF, and the Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs offered a binary framework on social media through which to understand the characters in the drama of OPE. The purpose of this analysis is to illuminate the symbolic mechanics by which the aerial campaign and ground invasion of Gaza were constructed as righteous and legitimate retaliatory violence in response to unacceptable and immoral offensive violence perpetrated by Hamas. How was the story told? How did events unfold, in what order? Who are the characters? What kinds of symbols and norms are drawn upon in the telling of the story.

The terror-trauma discourse

Trauma has long been fundamental to Jewish identity. From the destruction of the Temple in 70AD to exile and the horrors of the Holocaust, trauma and terror go hand in hand in the Jewish experience (e.g. Alexander 2004b; Alexander and Dromi, 2011; Ball, 2000; Zerubavel, 2002). Arguably, trauma has also been woven into Israel’s political identity since 1948, due to a perceived lack of support from the international community, “Arab terror,” and constant existential threat (Handelman and Katz, 1995; Yair, 2014). One interpretation of this observation is that trauma is a long-standing and durable background symbol for collective representations about terrorism in Israel.

After 9/11, terrorism was also presented in traumatic terms in the United States. For example, in the aftermath, media asked how the nation could “heal” and pointed to the resilience of American collective identity in the face of an evil existential threat. In other words, 9/11 merged terror and trauma discourses in the United States, long blended in the Israeli-Palestinian context, making trauma narratives an available background symbol for Israel’s state agents to construct a campaign likely to facilitate empathy from English-speaking audiences.

Conversely, narratives of Palestinian trauma are often denied (Sa’di and Abu-Lughod, 2007) and Palestinian invocations of trauma are even punishable by the state of Israel. The government of Israel has long characterized Palestinian nationalism and armed resistance as terrorism in both domestic and international arenas (Pappe, 2009).

When Palestinians who were expelled from their land and homes during the formal establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 attempted to return, they were labeled as “infiltrators” who returned to attack Jews (Morris, 1993). During the intifadas of 1987 and 2000, any Palestinian resistance, from stone-throwing to suicide bombing, was categorically labeled as terrorism, denying the alternative narrative of these times as the “shaking off” of occupation, which is the translation of intifada. Palestinian resistance against Israel’s continued blockade of Gaza after 2005 was also characterized as terrorism and led to the military operations Cast Lead (2008-2009) and Pillar of Defense (2012).

The so-called threat of Palestinian terror constitutes a key component of Israeli trauma narratives – a quotidian threat layered on top of multigenerational trauma over exile and genocide. More concretely, Israel’s actions are presented as moral and legal, and the state’s current plight is explained in light of Israel’s tragic past. Images of New York City burning then directly connect Israel’s military operations to the American military response to the “trauma” of 9/11. Conversely, Hamas is cast as a barbarous and irrational enemy with no legitimate claims to trauma, much like narrations about al Qaeda, the self-declared Islamic State, and the like.

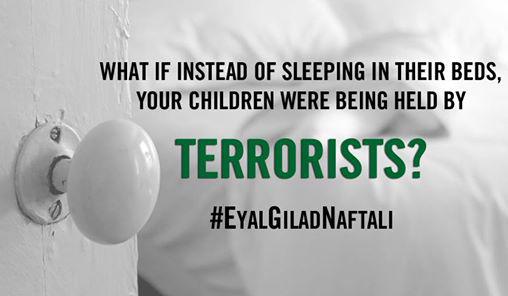

Israel’s state agents first used symbolic imagery and text to frame their plight as tragic and traumatized when the kidnapped Israeli-Jewish teenagers’ whereabouts remained unknown. Figure 1 (for all figures see below) draws on the universal imagery of a doorknob and symbolic colors like the green font often associated with Islam in general and Hamas in particular to ask audiences what they would do if they had to worry that their sleeping children may be harmed by terrorists. In this way, the domestic sanctuary of the bedroom can be disrupted at any time by the trauma of terrorist violence. This post evidences a securitization discourse: it offers a purely emotional appeal since actual rates of kidnapping as a tactic of terrorism are virtually nonexistent (Abulof 2014, Balzacq 2011, Buzan et al 1998).

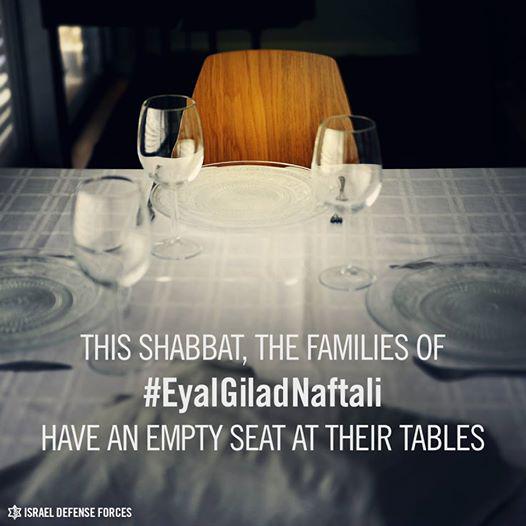

As seen in Figure 2, the Office of the Prime Minister reminded audiences that the families of the kidnapped boys “have an empty seat at their Shabbat table.” The simply set table and commonplace chair are meant to transport the viewer to their own dinner table. The image of the empty chair at the sacred Sabbath table, in particular, harkens back to all of the other empty chairs at Jewish Shabbat tables as a result of many, many losses over millennia. The empty chair, and the loss it symbolizes, fractures the family and community, thereby injuring the collective. The visual and narratological nature of the discourse extends trauma narratives to analogous rituals in the cultures and societies of the international social media audience.

The posts tie empty bedrooms and chairs in Israel to the traumatic emptiness of a space any loved one used to fill. Invocations of trauma are uniquely persuasive and silencing as they claim a moral high ground and set the chronology of offense and defense. Likewise, the denial of trauma is dehumanizing. Both are amplified when images and text are combined. The use of common and ordinary imagery makes plots and characters seem more familiar. Their repeated use influences culture more broadly, in ways that, in turn, further validate constructions of a virtuous state identity and “evil terrorists,” strengthening the alliances within and the Islamophobic framework of the hegemonic coalition in the “war on terrorism.”

In contrast to the justification of extreme means to prevent further trauma to the protagonists, social media discourse does not grant Palestinians in general and Hamas in particular legitimate rights to invoke their own trauma over occupation. For example, the Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs posted an animated YouTube video captioned:

You may have heard claims that Israel’s occupation of the Gaza Strip is the reason for hostilities in the region. Is this fact or fiction? Well, guess what: Israel DOES NOT occupy Gaza. It left Gaza in 2005, pulling out all its soldiers and leaving all its settlements. So who DOES occupy Gaza? Hamas. In 2007, this terrorist organization attacked the legitimate Palestinian Authority government and violently seized control of Gaza. It has ruled since then by force and without elections. Hamas turned the Gaza Strip into a terrorist base and uses its population as human shields (IMFA, 2014).

Claims that deny Israel’s control of Gaza’s sea and air space, the crossings between Gaza and Israel, and Gaza’s registry of population are part of a larger political effort to reject the Palestinian narrative of trauma. In 2009, The Guardian reported:

Israel’s education ministry…ordered the removal of the word nakba – Arabic for the ‘catastrophe’ of the 1948 war – from a school textbook for young Arab children…The decision will be seen as a blunt assertion by Binyamin Netanyahu’s Likud-led government of Israel’s historical narrative over the Palestinian one…Netanyahu…argued that using the word nakba in Arab schools was tantamount to spreading propaganda against Israel.

In sum, Israel invokes its own trauma and suppresses the trauma of Palestinians as its first tactic to sell its violent national security strategy to Anglophone social media audiences.

Analogical reasoning: “What would you do?” and “Hamas is ISIS”

Through posts such as Figure 3, Israel’s state agents expressed the urgency of the threat by asking audiences “what can you do in 15 seconds?” They contrast mundane activities such as tying ones’ shoes to Israeli civilians seeking shelter from rockets.

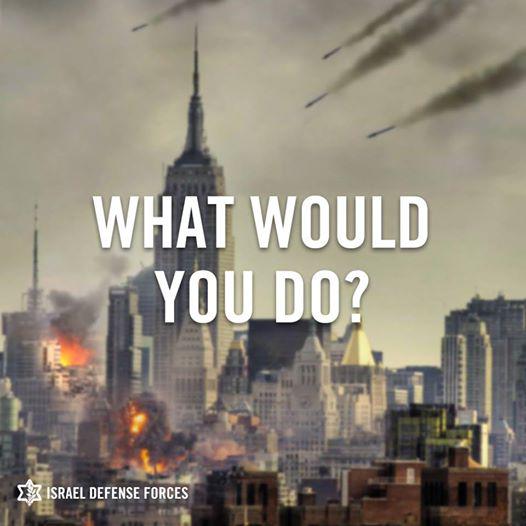

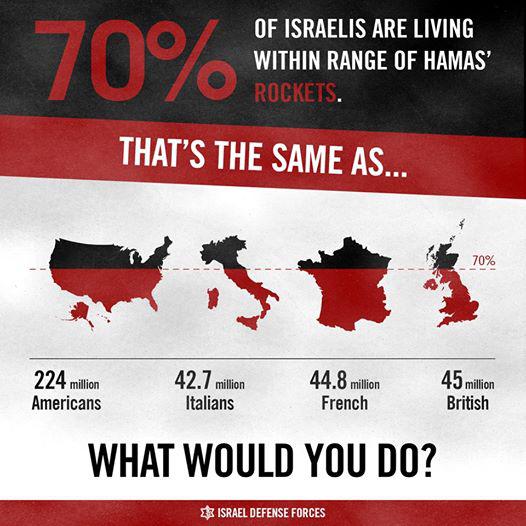

The most prevalent posts during OPE were images of global landmarks and capitals, ranging from New York’s Empire State Building, as seen in Figure 4, to Big Ben, the Eiffel Tower, and the Taj Mahal, as well as population maps, as seen in Figure 5, overlaid by the text “what would you do?” The series constituted the most explicit efforts to solicit empathy for the threat Israel faced. Israel often makes statements about how it is qualitatively different from its neighbors and more like the West, (e.g. “Israel is the only true democracy in the Middle East” (Netanyahu, 2015)), but the use of these images quite literally brings the violence home for a global audience. The range of global sites used presumably maximizes the international breadth of Israel’s supporters. Peter Beinart argues that Israel used this legitimization tactic because

Americans can identify with…being a powerful country attacked by Islamist terrorists. We don’t have to speculate about how we’d act. We know. And while we argue with each other about the wisdom of more recent military operations, we don’t generally question their morality. Herein lies the true brilliance of the “what would you do” question. It asks Americans to apply the same level of scrutiny to Israel’s ‘war on terror’ that we apply to our own. And it works because, overall, our level of internal scrutiny isn’t that high.

To solidify the analogical reasoning of the social media campaign, state agents compared Hamas – a group with local aims including self-determination of which international audiences may not be immediately aware – to “ISIS” – a group with global reach and imperial aspirations that international audiences would surely know about due to widely publicized acts like the beheading of American journalist James Foley during the time frame under study and subsequent attacks in France and Belgium, among others. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu explained,

Hamas is ISIS and ISIS is Hamas. They act in the same way. They are branches from the same poisonous tree. They are two extremist Islamic terrorist movements that abduct and murder innocents, that execute their own people, that shrink at nothing including the willful murder of children. Both movements are, in effect, making an effort to establish Islamic rule, caliphates, without human rights, across wide areas, by slaughtering minorities, by not respecting the human rights of anyone – neither women nor men, nor children, nor Christians, nobody.

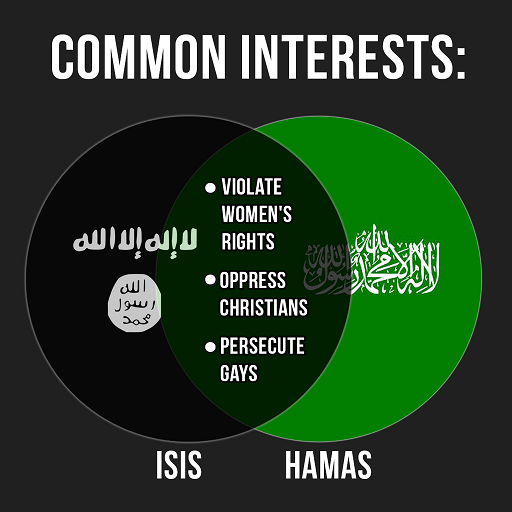

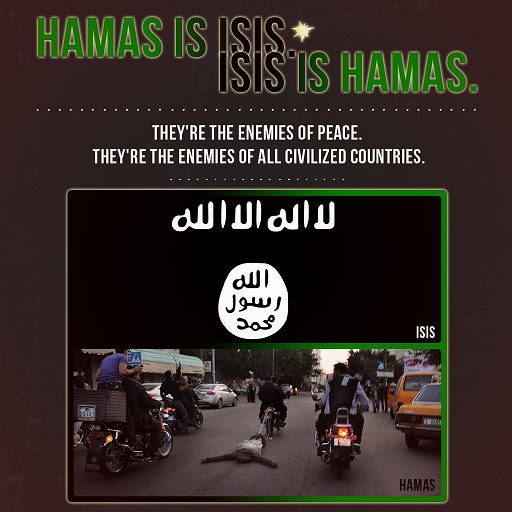

This message was reinforced with posts such as Figures 6 and 7, one using a Venn-diagram to highlight the two groups’ overlap and the other using a violent image of a body being dragged through the streets by a motorcycle. Posts recounting the violence common to both organizations reinforce Israel and the West’s shared moral values. More, this comparison eclipses grievances about the legacies of colonialism. “Terrorist” claims to victimhood – whether Hamas’s framing of its rocket fire as defensive retaliation in the face of an untenable military blockade or ISIS’ framing of the establishment of a multinational caliphate as a way to roll back the injustices of colonization – can be undermined by drawing comparisons between groups based their common opposition to everything the “civilized world” stands for. In sum, using analogical reasoning and direct comparisons is a second aspect of the symbolic mechanics of Israel’s social media strategy.

Righteous legitimacy and nefarious illegitimacy

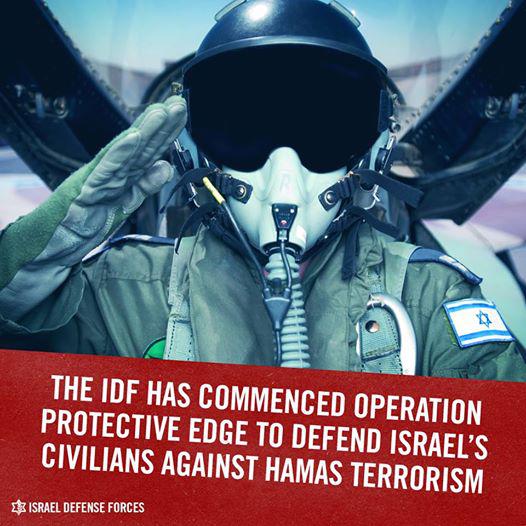

Figure 8 establishes Israel as a legitimate state actor, deploying its army for the just cause of defending its people. The pilot is saluting, wearing military gear with an Israeli flag patch, inside a jet, presumably used in the first week’s air strikes against Gaza. The image itself allows its viewer to empathize with the helmeted jet pilot who could be any Israeli conscript, while the text transforms the image into an announcement of the start of the war. Israel’s position is clearly defined as defensive against the illegitimate use of force labeled “Hamas terrorism.”

In Figure 9, several heavily armed men in black t-shirts and masks are labeled as “the people Israel fought in Gaza.” Unlike the anonymous state-sanctioned Israeli soldier, emphasizing Hamas’s use of masks is a securitizing move. It anonymizes them in ways that dehumanize and delegitimate. Without a uniform, they seem like criminal, non-state terrorists whose use of force is never legitimate, but in reality, Hamas is the democratically elected leadership of Gaza. Moreover, these images draw on a long legacy of characterizing all Palestinian resistance as terrorism in Israeli government rhetoric, news media, and academic literature. This construction relies on a long-standing narrative that Jews have biblical and historical rights to the land, while Palestinians declined opportunities to live peacefully as neighbors and have opted to use force.

Conversely, one of the ethical cornerstones of Israeli classification of the IDF as “the most moral army in the world,” is the notion of “purity of arms.” According to the IDF code of ethics posted on their English language blog,

The IDF servicemen and women will use their weapons and force only for the purpose of their mission, only to the necessary extent and will maintain their humanity even during combat. IDF soldiers will not use their weapons and force to harm human beings who are not combatants or prisoners of war, and will do all in their power to avoid causing harm to their lives, bodies, dignity and property.

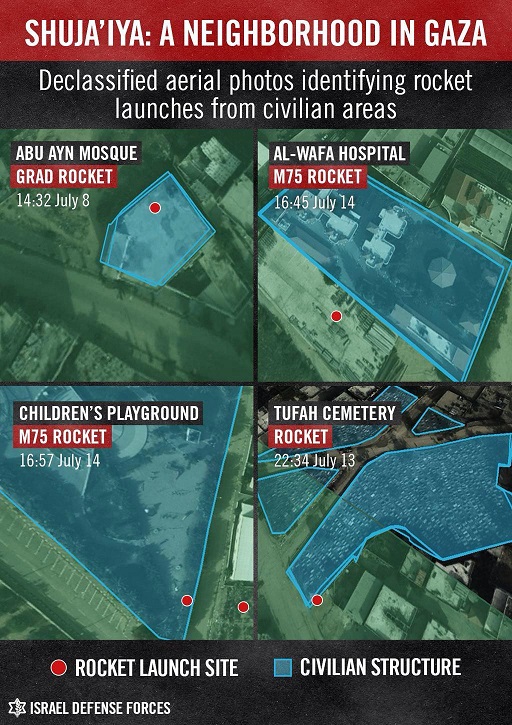

Figure 10 depicts a declassified aerial photo shared during the airstrike phase of the operation of a densely populated, civilian neighborhood in Gaza to demonstrate Israel’s commitment to operational transparency. More, it indicates that Hamas decided to embed its terrorist infrastructure within their own civilian population, justifying Israel’s choices in controversial targets and the discrepancy in civilian causalities between the two sides.

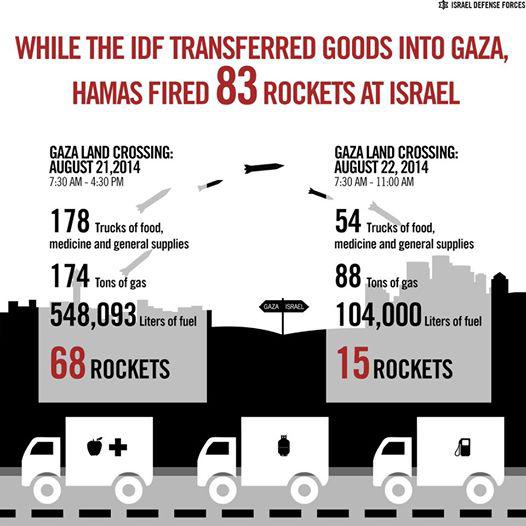

Across social media platforms, the IDF emphasized its concerted effort to limit civilian casualties by dropping leaflets, firing warning shots, and sending text messages prior to air strikes, and, as reported in Figure 11, Israel continued to provide essential foodstuffs, medical supplies, and gas to Gaza throughout the operation. This messaging about Israel’s moral humanitarianism is not unique to this particular war. According to Breaking the Silence, a collective of former IDF soldiers,

The state’s spokespeople argue that Israel does not withhold basic necessities from Palestinians or take actions that prompt humanitarian crises. Instead, despite its security needs, Israel ensures the Palestinian ‘fabric of life.’ These claims…are intended to suggest that life under Occupation can be tolerable, and that there is nothing to prevent Palestinians from living reasonably well (207).

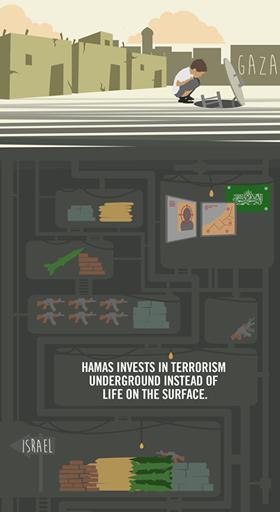

In addition to directly contrasting Israel’s moral actions and Hamas’s refusal to reciprocate, Israel’s state agents also featured Hamas’s network of “terror tunnels” as evidence of their immorality. Figure 12 represents the most common argument about the tunnels shared across social media: “Hamas invests in terrorism underground instead of life on the surface.” This tagline serves as a structural and geographic metaphor for motive (and a symbolic complement to the images of masked insurgency – tunnels and masks both conceal). The contrast between investment underground, bringing to mind hidden motives, and life on the surface, a signifier for transparency, reinforces narratives of Israeli morality and Hamas’s depravity. The image of the small child crouching then reframes the narrative about the tunnels within the binary of Israeli concern for life and Hamas’s blatant disregard for the life. Images of children facilitate securitization by making a very specific point about a military strategy during a particular operation emblematic of an existential threat; bringing to mind all of the suffering, lost, and deceased Israeli children throughout the history of the conflict, due to so-called immoral Palestinian violence.

In sum, the third salient tactic for selling OPE to Anglophone social media audiences, particularly in the United States, is to emphasize Israel as a nation-state that wields legitimate and defensive force in the face of illegitimate non-state actors who have no right to use force.

Conclusion

At the conclusion of Operation Protective Edge, the United Nations estimated that more than 2,100 Palestinians were killed, along with 66 Israeli soldiers and seven civilians in Israel. This grossly disproportionate statistic may not sway public opinion toward the plight of the Palestinians, but perhaps further study of Israel and other states’ legitimization tactics on social media can give us insights that allows us to more deeply understand the durable background symbols that make social media posts powerful, effective, and convincing in the realm of national security.

Figures

Figure 1 – https://www.facebook.com/idfonline

Figure 2 – https://www.facebook.com/IsraeliPM

Figure 3 – https://www.facebook.com/idfonline

Figure 4 – https://www.facebook.com/idfonline

Figure 5 – https://www.facebook.com/idfonline

Figure 6 – https://www.facebook.com/IsraeliPM

Figure 7 – https://www.facebook.com/IsraeliPM

Figure 8 – https://www.facebook.com/idfonline

Figure 9 – https://www.facebook.com/idfonline

Figure 10 – https://www.facebook.com/idfonline

Figure 11 – https://www.facebook.com/idfonline

Figure 12 – https://www.facebook.com/IsraeliPM

References

Abulof U (2014) Deep securitization and Israel’s “demographic demon.” International Political Sociology 8(4): 396-415.

Alexander JC (2004b) Cultural trauma and collective identity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Alexander JC and Dromi S (2011) Trauma construction and moral restriction: The ambiguity of the Holocaust for Israel. In Narrating trauma: On the impact of collective suffering. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers, pp. 107-132.

Ball K (2000) Introduction: Trauma and its institutional destinies. Cultural Critique 46: 1-44.

Balzacq T (2011) A theory of securitization: Origins, core assumptions, and variants. In Securitization theory: How security problems emerge and dissolve. New York: Routledge.

Buzan et al (1998) Security: A New Framework for Analysis. New York: Lynn Rienner.

Handelman D and Katz E (1995) State ceremonies of Israel: Remembrance Day and Independence Day. In: S Deshen, CS Liebman, and M Shokeid (eds.) Israeli Judaism: The sociology of religion in Israel. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, pp. 75–86.

Morris B (1993. Israel’s border wars, 1949-1956: Arab infiltration, Israeli retaliation, and the countdown to the Suez War, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Netanyahu B (2015) Full transcript of Netanyahu’s address to UN General Assembly. Available at: http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/1.678524 (accessed November 2, 2016).

Sa’di AH and Abu-Lughod L (2007) Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the claims of memory. New York: Columbia University Press.

Yair G (2014) Israeli existential anxiety: Cultural trauma and the constitution of national character. Social Identities: Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture 20 (4-5): 346-362.

Zerubavel Y (2002) The “Mythological Sabra” and Jewish past: Trauma, memory, and contested identities. Israel Studies 7.2: 115-44.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Dangers Within Humanitarianism to Israel’s National Security

- Assessing One-State and Two-State Proposals to Solve the Israel-Palestine Conflict

- Israel: A Democratic State?

- Opinion – Confronting Israel’s Annexation Plans: From Fear to Hope

- Why Jerusalem Is the Capital of Israel – And Palestine

- Opinion – Israel-Palestine Policy Under Biden