On March 8, 2018, at least 400,000 people took to the streets in more than a hundred cities in Spain. Barcelona and Madrid were swept by protests that went on for the whole day. In addition, millions of workers, women joined by men, participated of partial or 24-hour strikes called by feminist organizations and ten trade unions across the country. Spain was one of the epicenters of a transnational campaign calling for feminist strikes and protests all over the world, in at least 170 countries. Since 2016, feminist activists and women’s groups have often gone into strike as a form of protest, as a “repertoire of contention” (Tilly, 2015, p. 41). Argentina, Paraguay and Poland, to name a few, witnessed historical protests and strikes over the last years, which denounced recurrent cases of violence against women and conservative threats against women’s reproductive rights (Friedman & Tabbush, 2016). Such demonstrations were not confined to the very streets occupied by protesters around the world. Women’s and feminist groups combined their presence in multiple arenas and engaged in various contentious practices. The demonstrations were trending on Twitter worldwide, and activists were also sending, via Facebook and Instagram, live videos and pictures before, during and after International Women’s Day on the 8 March 2018. The protesters wanted to spread urgent messages: any form of oppression or inequality based on gender needs to be addressed and eliminated.

Strikes are consolidated and modular repertoires of contention, recurrently used along social movements history for at least 300 years (Tarrow, 2009, p. 131). Workers all over the world go on strike in order to strengthen their positions in relation to employers or the State, to collective bargain for demands, or to offer mutual support (Tarrow, 2009, p. 132). Going on strike implies provoking changes in the routines of production of material or immaterial goods, either complete or partial stops. In the case of workers’ strikes in general, it puts into perspective the value of the time and energy spent by them to ultimately generate profit, which may be taken for granted. Such a concept has been expanded and reappropriated by women’s groups to shed light on pressing gender inequality issues.

Strikes are also an important landmark in the history of feminist contentious politics. In the beginning of the 20th century, trade unions and workers leagues were intensively protesting against the very precarious work conditions of women in the North American textile industries (Hermanson, 1993). The 1908-1910 women’s strikes in New York, including the “uprising of the 20,000” were unprecedented episodes of women’s mobilization (Durkin, 2008). In 1911, the tragic Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in New York City, which ended with 146 dead migrant workers, culminated to add symbolic meaning to the 8th of March as the international women’s day, a day to engage in resistance (Durkin, 2008).

Furthermore, there is another historical strike which is an important reference for feminist activists and social movements’ organizations: the 1975’s Icelanders national strike. On that episode, 90% of women in the country refused to work, do housework or care for one day. The strike intended to clearly show the relevance of women’s participation in society, but most importantly to call attention to gender gaps and patriarchal roles, and to show that women were actively fighting against them.

Such a legacy is part of the strategic and cultural references that inform how women mobilize nowadays. From the repertoires of contention they came to know, adapt, create and put into practice, they chose to call for a feminist strike, which encompasses a more comprehensive understanding of gender inequalities than general labor strikes. It means they intended to generate specific outcomes and impacts in order to have their demands recognized as valid and responded to. In that sense, suspending women’s presence and contribution from public and private spheres makes visible the sexual division of labor, the burden of unpaid care work, the unequal salaries. They stopped to denounce the overlapping oppressions women still face as part of their existence in patriarchal societies. They were clearly showing the personal is political.

The 2018M strikes did not took place only in Spain: women all over the world striked and protested, following the examples of the women’s strike in Poland and the Black Wednesday women’s strike in Argentina, both in 2016 (Friedman & Tabbush, 2016). Moreover, the 8 March, 2017 women’s strike was a stepping stone that showed it was possible to organize a large transnational event in 2018. Coalitions such as La Internacional Feminista helped to bring together groups and activists, to produce material, to track the events in different cities and to follow up the numerous demonstrations. Besides local meetings and national commissions, activists also coordinated among themselves via Facebook groups, Instagram, Telegram and e-mail lists, posting updates, suggestions and sharing resources and ideas. The 8th of March is an emblematic date that tends to concentrate multiple events, but in 2018 there was an specific effort to call for a strike, to stop daily routines and make women’s absence visible.

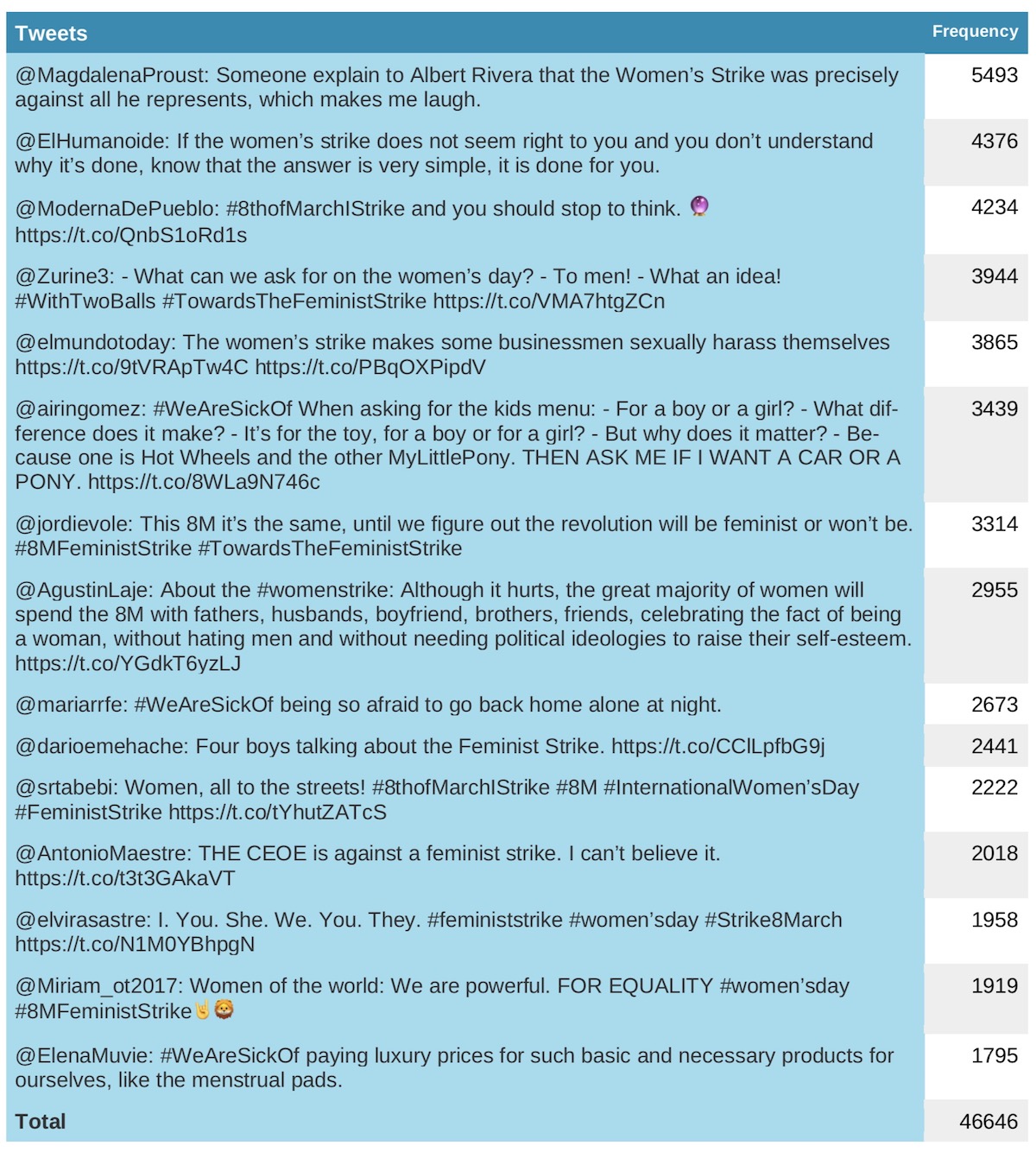

On Twitter, the 2018M women’s strike was also intensively discussed: a significant part of the messages intended to expose, to stand for the reasons behind the strike or to call women to the streets, while others responded to opposite arguments. On the chart below, we present the 15 most retweeted messages from 596,622 tweets containing hashtags related to the strike, collected from Twitter’s Application Programming Interface (API) between February 13th and March 13th, 2018. We can see that one of the greatest struggles was still to convince others there were enough and justifiable reasons to strike, that women still face multiple conditions of gender oppression. The posts shared also used humor and daily situations to generate empathy and to show how in the most simple situations women are treated differently, and often violently. Among the injustices they denounced were gender stereotypes, lack of reproductive rights, unreal beauty patterns, sexual violence, lack of political voice and economic inequalities.

The 15 most retweeted tweets related to the 2018M women’s strikes

Source: tweets database collected by the author from Twitter’s API. All of the tweets were translated from Spanish by the author.

The 2018 women’s strike in Spain was organized for eleven months, as different groups and activists built a network across the different communities of the Spanish State (Borraz, 2018). From April, 2017, feminist social movements and those women interested gathered for monthly meetings and neighborhood events (Boraz, 2018). Later on, hundreds of activists envisioned and planned the Spanish women’s strike campaign as they participated of two national encounters, the Encuentros in Elche and Zaragoza, in September, 2017 and January, 2018. Such articulation was crucial to build a national campaign, in which multiple organizations called to mobilize not only working women, but also students, children, the elderly (see map below). In Catalunya, for instance, more than 300 organizations supported the strike. The organizing commissions across Spain proposed a broad strike, which included stopping care responsibilities, buying products, working and studying. As the organizers declared,

It is not our aim to organize a “classic” workers strike but to go beyond this format: our plan is to paralyze all the different invisible tasks and activities that women usually do, in all different levels and places. Specifically, we call a housework and care strike in the private field, a labor strike and a consumers strike (both in the public field) and a students’ strike in all educational levels.

Although it was historically successful, the women’s strike in Spain was still internally and externally contentious. During the preparations, the groups and commissions battled to have different specific demands included. In the Barcelona meetings, the participation of migrant women was crucial to bring to the table the issues of precarious labor, extreme exploitation conditions, and systemic xenophobia experienced by them in Spain. Although the strike was organized by commissions that had members from different backgrounds and experiences, some women still felt their struggles and views were not included in the demands of the Catalunya’s regional manifesto. I participated in eight various meetings with activists, and it was clear there were tensions regarding different views of what the strike should be primarily about, what would be the main demands and which allies they would gather.

There were groups arguing the strike would benefit from having men as supporters, because that would mean the national and economic impact would be greater, as much as its repercussion. On the other hand, other women affirmed the strike should have them as protagonists, their absence should be acknowledged and reflected upon. Some student groups were particularly in favor of a mixed strike, after arguing that gender oppressions go hand in hand with the huge economic inequalities reproduced in capitalist societies. For them, these are two problems that should be faced as interdependent.

The internal disputes also related to the different and intersectional experiences these women went through. Multiple generational, cultural, political and economical perspectives brought to light issues that some face but others do not, which challenged them to discuss and address contradictions, but also to search for shared consensus. It is an on going struggle, in which these women (re)elaborate their understandings of new political paradigms. Feminist and women’s movements have tried to put into question systemic injustice mechanisms.

The 2018 feminist strike in Spain was a historic event: hundreds of thousands went to the streets, transportation services went into partial strike and the world looked closely at what those women had to say. The organizers were successful in coordinating nationally and joining what was a transnational campaign to make visible gender oppression. Calling for a feminist strike meant those groups and activists did not only want to publicize their demands, but to generate a broad impact that would be felt on the social organization of public and private spheres. Although successful, the women’s strike in Spain and in Barcelona was a contentious process, before and after it took place. However, it means these women are building new networks, sharing routines and ideas, (re)assessing and (re)combining their understandings of their political presence and views. Such process is disputed inside and outside these groups, but most importantly, it has opened crucial debates towards a more inclusive society.

References

Borraz, M. (2018). Espanha: como se gestou a grande greve feminista. Retrieved April 10, 2018 from https://outraspalavras.net/destaques/espanha-como-se-gestou-a-grande-greve-feminista/

Dias, T. (2018). 8 de marzo y la Huelga Feminista en España: luchas disruptivas y tecnopolítica. Retrieved March 24, 2018 from http://tecnopolitica.net/content/8-de-marzo-y-la-huelga-feminista-en-espa%C3%B1a-luchas-disruptivas-y-tecnopol%C3%ADtica

Durkin, K. (2008). A rich tradition: International Women’s Day. Retrieved April 10, 2018 from https://www.workers.org/2008/us/iwd_0313/

Friedman, E. J., & Tabbush, C. (2016). #NiUnaMenos: Not One Woman Less, Not One More Death! Retrieved December 31, 2016, from http://nacla.org/news/2016/11/01/niunamenos-not-one-woman-less-not-one-more-death.

Hermanson, J. (1993). Organizing for justice: ILGWU returns to social unionism to organize immigrant workers. Labor Research Review, 1(20), 8.

Tarrow, S. (2009). O poder em movimento: movimentos sociais e confronto político. Petrópolis: Vozes.

Tilly, C. (2015). Popular Contention in Great Britain, 1758-1834. Routledge.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Spain’s Request For NATO Coronavirus Aid: Will Turkey Answer?

- A Global Movement to End Violence against Women in Politics and Public Life

- Gender Troubled? Three Simple Steps to Avoid Silencing Gender in IR

- Opinion – It’s Time to Redefine Gender Mainstreaming

- Gender-Transformative Peacebuilding in Colombia

- Opinion – The Gendered Consequences of Coronavirus