Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Are Islam and Democracy Compatible?

3. Framework to Evaluate Islamist Parties

4. Case Studies and Lessons Learned

4.1 Hamas

4.2 Hizbullah

4.3 Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood

5. Policy Recommendations

Abstract

In order to support democracy development efforts in the Middle East, Western policymakers must be guided by a realistic and nuanced view of the region. Militancy and terrorism in the region have traditionally been viewed in terms of simple dichotomies and broad generalizations. To address this issue, this paper offers a framework for the evaluation of Islamist political parties and their participation in the varied political systems of the Middle East, and it provides policy recommendations for democratic development in the Middle East. Three case studies and their respective “lessons learned” are presented as evidence for the final policy recommendations of the paper. The case studies are that of the Palestinian Hamas, the Lebanese Hizbullah, and the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood.

1. Introduction

Recent political events in the Middle East signal the need for an urgent re-evaluation of the political playing field and the Islamist actors within it. In Iraq and Afghanistan, U.S.-led military interventions have been followed by attempts to build democratic systems of governance. Electoral gains by the parties linked to Moqtada al’Sadr’s Mehdi militia in Iraq; by Hamas in Palestine; and by Hizbullah in Lebanon have made some in the West doubtful that democracy should indeed be sought in the region. However, peaceful Islamists such as the AKP in Turkey and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt have also seen electoral success; a signal that both militant and peaceful Islamists have broad bases of support and general credibility in much of the region. Islamist parties and movements exist in most, if not all, countries in the Middle East, and their longstanding popularity suggests that instead of ignoring them, policy makers must try to understand them, analyze them, and engage with them.

2. Are Islam and Democracy Compatible?

There are two opposing viewpoints about the relationship between Islam and democracy that shape Western attitudes towards Islamist parties, and often the question about the compatibility of Islam and democracy is at the heart of this debate. There are those that argue that Islam is incompatible with democracy and, in light of the recent electoral successes by Islamist groups, it would be unwise to advance democracy in the region. Middle East scholar Vickie Langohr notes that those who are skeptical about the compatibility of Islam and democracy generally advance one of two arguments. The first is procedural: that although some Islamists have seemingly opted to effect change through the ballot box, they have chosen this method only because they do not yet have the power to use more forceful means. The second argument is that Islamists seek to impose Sharia, but considering that Sharia itself is discriminatory, it follows that Islamists will use their power to impose undemocratic policies.1 Historian Elie Kedouri succinctly captures this first point of view, claiming that democracy “is alien to the mind-set of Islam.” 2 Another statement that frequently surfaces is that Islamists only believe in one man, one vote and one time. This latter argument is commonly cited by autocrats in the as rhetoric to stymie progress towards democracy, since they argue that democratic elections would lead to the installment of Islamic theocracies.

The opposing viewpoint is that Islam is in fact compatible with democracy. Proponents of this view point to specific concepts in Islam which support this thesis; for example, in the Qur’an, the righteous are described as those people who, among other things, manage their affairs through “mutual consultation” or shura.3This is expanded through traditions of the Prophet and the sayings and actions of the early leaders of the Muslim community to mean that it is obligatory for Muslims, in managing their political affairs, to engage in mutual consultation. Both Sunni and Shiite scholars have stressed the importance of consultation in Islam when it comes to the affairs of the people. For example, Ayatollah Baqir al-Sadr, the Iraqi Shiite leader who was executed by Saddam Hussein said that “the people have a general right to dispose of their affairs on the basis of the principle of consultation.”4 Iranian Islamic reformist Abdul Karim Soroush has argued that “Islam and democracy are not only compatible, their association is inevitable. In a Muslim society, one without the other is not perfect.”[1] According to him, “the will and beliefs of the majority must shape the ideal Islamic state… Islam itself is evolving as a religion, which leaves it open to reinterpretation.”5 Citing such examples those in support of reaching out to Islamists have argued that there is nothing inherently contradictory between Islam and democracy and that Islamist groups can in fact be incorporated into a democratic system.

Aside from religious arguments there are several examples of Islamic oriented political parties that operate successfully in the political systems of predominantly Muslim countries. In Turkey, the Justice and Development Party (AKP), shares many Western political stances and advocates a liberal market economy and Turkish membership in the European Union.6 The AKP has been able to demonstrate that an Islamic party can govern while respecting the principles of modern democracy. In Indonesia, when the military regime of Suharto came to an end, the first democratically elected president was Abd al-Rahman Wahid, the leader of one of the largest Islamic organizations in the world. Even though he participated in the democratic system as a clearly identifiable Islamic leader, al-Rahman Wahid did not campaign on a platform of Islamizing the political system.7 The cases of Turkey and Indonesia have therefore proven that Islam and democracy can indeed be compatible.

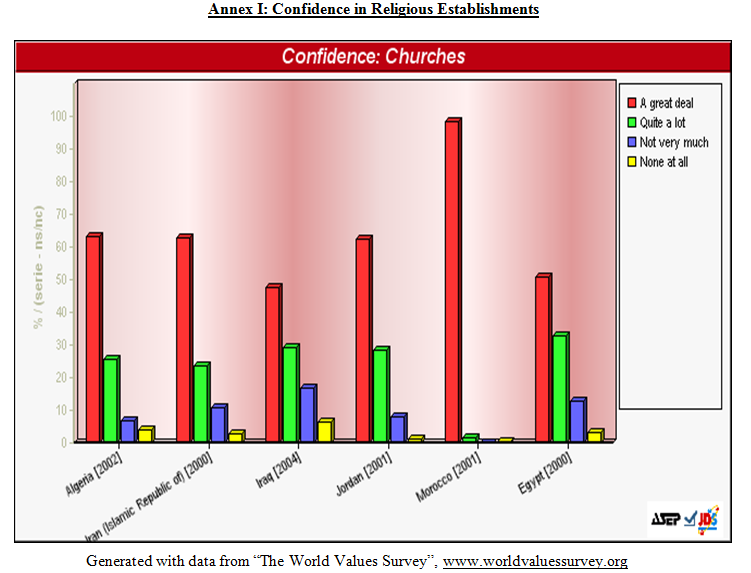

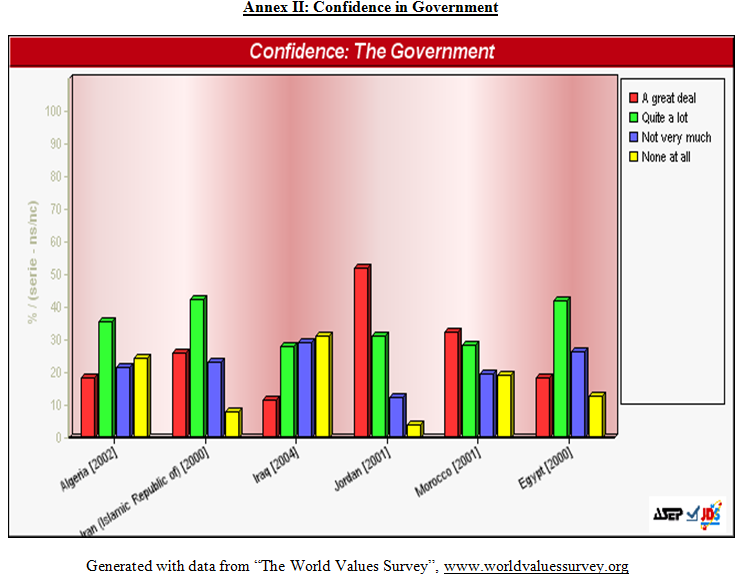

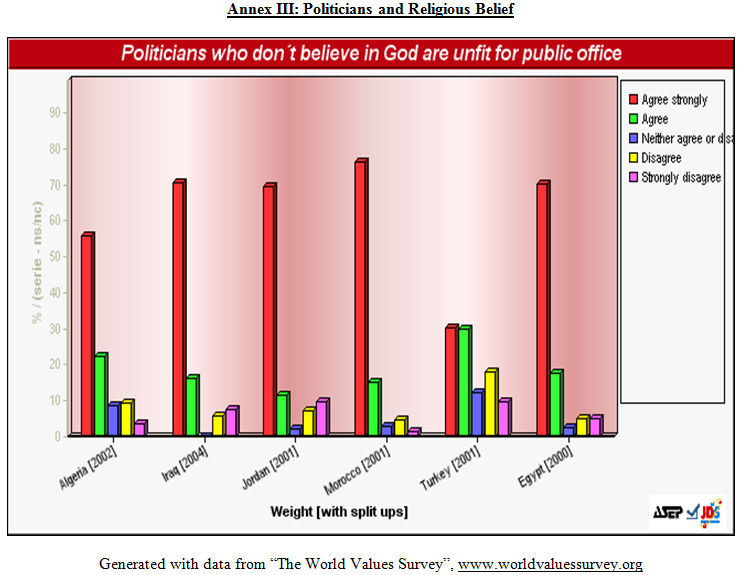

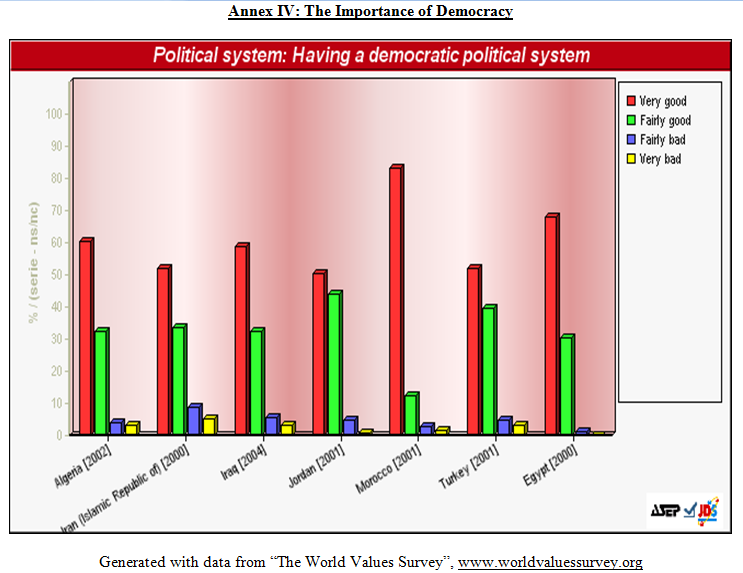

Regardless of Western political opinions on Islamist movements and parties, it is clear that militancy and democracy are not mutually exclusive in the Middle Eastern context. Islamist groups which are at once violent may simultaneously engage in the democratic process. In the near future, we can expect that such groups will continue to garner support since Middle Eastern citizens trust their religious establishments (see Annex I) – and those who profess loyalty to them – to a much greater degree than their governments (see Annex II). The future of Middle Eastern democracy is also, in all likelihood, an Islamic democratic future, as Middle Eastern populations (even in officially secular Turkey) overwhelming seek politicians who are religiously-oriented (see Annex III). In addition, it is apparent that democracy is not dismissed in the region; instead, it is viewed as both desirable and worthy of pursuit (see Annex IV).

3. Framework to Evaluate Islamists

Recognizing that Islamist parties are a political reality in the Middle East, what should be the Western response? When it comes to Western attitudes and policies towards the Middle East, the first hurdle is to resist the tendency to group all Islamist parties and movements into one category. When any party with a religious affiliation is grouped with the likes of Al Qaeda, strategic thinking and productive policy is handicapped, to great detriment. The reality of Islamist parties is significantly more nuanced, as well as more promising. Before examining the cases of several Islamic parties, it is therefore essential to understand the fault lines between groups to craft sensible policy towards them.[2] This can best be done with a framework as a point of reference.

In the literature, the most commonly used classification makes the distinction between armed jihadists (al Qaeda); militant organizations (Hamas and Hizbullah); and peaceful Islamists (Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood).[3] Although simple, this categorization is a useful first step. Within these categories, there is significant diversity. Furthermore, many analysts accuse Islamist parties of “double speak”: publishing one description of their platform and goals in English, and another less liberal version in Arabic.[4] Instead of meticulously picking through documents to discover Islamist parties’ “real” intentions, Hamzawy and Brown suggest that it is more worthwhile to examine the political system in which these Islamist parties operate to better understand them and to craft informed and nuanced policy.[5] The categories set forth by these authors are weak or failed states; inclusionary states (though not necessarily democratic); and exclusionary states.[6]

In the first category, weak and failed states, the authors describe several shared characteristics: there are “significant individual and organizational freedoms, plurality in the political system, and anemic state organs with little capacity to maintain law and order.”[7] In such states there is instability and most parties, not just Islamist parties, create or maintain militias. For example, in Iraq, Lebanon, and Palestine, nearly every political party or grouping-left, right, religious, secular-has a military wing.[8] This is not to say that militant activities of political parties are excusable, but just that Islamists in these situations should not be singled out.

The second category is that of inclusionary states which allow some political space for opposition parties, though they should not be mistaken for open liberal democracies. Algeria, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Morocco have allowed Islamist parties to participate in the political system to varying degrees. In general, Islamist parties in these countries share three characteristics: “respect for the institutional framework of the state in which they operate; acceptance of plurality as a legitimate mode of political existence; and a gradual retreat from ideological debates in favor of a growing concentration on pragmatic agendas that are primarily concerned with influencing public policies.”[9] Such parties have shown political maturity, yet might loose patience if the openings experienced to date are the full extent of “democratization” of the political processes in their respective countries.

Finally, there is the category of semi-authoritarian states that leave little political space for any opposition and whose treatment of Islamist parties are varied and unpredictable. Consequentially, parties tend to adopt unsteady strategies: sometimes they are highly critical of the state, and at other times they try to appease the strong-man ruler to avoid a clampdown. Such has been the case in Egypt and Sudan, and more recently in Jordan and Yemen. Hamzaway and Brown argue that “the most promising way to facilitate the transformation of such Islamist movements into responsible political actors is to guarantee them a stable mode of participation.”[10] This, they acknowledge, can only be done by the ruling elites.

The political context in the Middle East must not be regarded as uniform. By examining not only the Islamist parties themselves, but also the context in which they operate, blueprints can be laid for a nuanced Canadian policy towards democratization in the Middle East that need not pose a tradeoff between ballots and bullets. In the next section, the history of Hamas, Hizbullah, and the Muslim Brotherhood will be examined, as well as past and present Canadian policy towards them.

4. Case Studies and Lessons Learned

4.1 Hamas

Hamas is the largest and most influential Palestinian Islamist movement. In Arabic, the word “hamas” means zeal, and is also an acronym for “Harakat al-Muqawama al-Islamiya,” or Islamic Resistance Movement. Hamas grew out of the Muslim Brotherhood, a religious and political organization founded in Egypt with branches throughout the Arab world. Beginning in the late 1960s, Hamas founder and spiritual leader, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, preached and did charitable work in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. In 1973, Yassin established al-Mujamma’ al-Islami (the Islamic Center) to coordinate the Muslim Brotherhood’s political activities in Gaza, and in December 1987 he officially founded Hamas as the Muslim Brotherhood’s local political arm following the eruption of the first intifada.The group published its official charter in 1988, moving decidedly away from the Muslim Brotherhood’s ethos of nonviolence.[11] The group combines Palestinian nationalism with religious fundamentalism; its founding charter commits the group to the destruction of Israel, the replacement of the PA with an Islamist state on the West Bank and Gaza, and to raising “the banner of Allah over every inch of Palestine.”[12] Historically, Hamas has operated in Gaza and the West Bank as in opposition to the Palestinian Authority (PA) government dominated by the secular Fatah.

Hamas is both a militant organization as well as a mass social, political and religious movement. Hamas military and political leaders are based throughout the West Bank and Gaza and the organization maintains offices and representatives in Teheran, Damascus and Amman.[13] Its military wing, Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigade, has carried out attacks against Israel using suicide bombings, mortars and short-range rockets. In addition to its military activities, Hamas devotes much of its financial resources to an extensive social services network: the group funds schools, orphanages, mosques, healthcare clinics, soup kitchens and sports leagues. It is estimated that approximately 90 percent of Hamas’ budget is spent in social, welfare, cultural and educational activities.[14] The Fatah-led Palestinian Authority often fails to provide such services and the officials are notoriously corrupt; in contrast, Hamas’ social service provision and their repuation for honesty helps to explain their broad popularity and support in recent years. Much of Hamas’ funding that allows them to provide social services is known to come from Palestinian expatriates and private donors in Saudi Arabia and other oil-rich Gulf states. Iran is also known to provide significant support to Hamas which is estimated to be in the range of to $20 million to $30 million per year.[15]

At its beginning, Hamas was seen by Israel as a potential partner to balance the secular Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and its dominant faction, Yasser Arafat’s Fatah. The Israeli government officially recognized al-Mujamma’ al-Islami, the precursor to Hamas, by registering the group as a charity. This allowed Mujama members to set up an Islamic university and to build mosques, clubs and schools. Crucially, Israel often stood aside when the Islamists and their secular left-wing Palestinian rivals battled, sometimes violently, for influence in both Gaza and the West Bank.[16] Additionally, while Israel hunted down members of Fatah and other PLO factions in Gaza, it dropped harsh restrictions imposed on Islamic activists by the territory’s previous Egyptian rulers. Moreover, Gaza’s Israeli military governor at the time, General Yosef Kastel, had regular contacts with Sheikh Yassin, visiting his mosque and meeting with the cleric many times. In one instance, General Katsel even arranged for the sheikh to be taken to an Israeli hospital for treatment. According to the General, “Israel’s main enemy was Fatah and the cleric was still 100% peaceful towards Israel.”[17] However, in the early nineties, unlike Yasser Arafat’s Fatah, Hamas refused to accept the Oslo peace process or to recognize the state of Israel. At that point, Hamas replaced the PLO as Israel’s main target in the Palestinian territories. In the years following the Oslo accords, Hamas leaders intensified their rhetoric against Israel and vowed to derail the peace process through violent attacks. Hamas launched its first suicide bombing attack against Israel in April 1994.[18]

Hamas in Politics

In recent years Hamas has been on the rise politically in the Palestinian territories. Hamas began large-scale participation in the political scene in 2005 and made a strong showing in local municipal elections in the occupied territories, especially in Gaza: Hamas won 77 out of 118 seats in ten council elections. It was in January 2006, however, that Hamas caused a major upset in Palestinian politics by winning a majority in the Parliamentary elections, winning 74 out of 132 seats while Fatah, the Western backed and dominant party in the PLO, won only 45 seats.[19] The recent political activities of Hamas are a contrast to its previous strategy of boycotting Palestinian elections. Realizing the political gains made by other Islamist movements in elections throughout the region, Hamas has in recent years reversed its boycott and decided to engage directly in Palestinian politics. Since this change there has been a renewed emphasis on Hamas’ connection to its forerunner, the Muslim Brotherhood, in order to gain a “softer” Islamic image and regional acceptance. The group has also presented a political program in competition with that of the Palestinian Authority, based on a readiness to accept the principle of “stages” as a solution to the Palestinian problem which is similar to the PLO’s “stages” program adopted in 1974.[20] It was also widely noted that during the 2006 election campaign, some Hamas candidates made pragmatic statements indicating that they might deal with Israelis in certain situations. This new attitude towards political engagement coupled with a self imposed moratorium on suicide attacks raises new questions as to whether Hamas may transition into a peaceful political movement as the PLO did earlier.

The recent political gains of Hamas are significant because they exemplify the results of a growing trend in recent years of Arab and Muslim electorates who are fed up with corrupt secular governments and increasingly turning towards Islamist parties. Recent democratic elections in the Middle East have led not only to victory for Hamas in Palestine but also to impressive showings by both Shiite and Sunni religious parties in Iraq, Hizbullah in Lebanon and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt.[21] Islamists have demonstrated great electoral success in the Middle East largely because of the socio-political environment that exists in the region. In a region where corrupt dictators, weak democratic movements and military occupation are common, Islamists have come to be seen as the solution to society’s ills. Hence, Hamas’ political gains are the result of years of Israeli military occupation and corrupt Palestinian leadership that has for too long failed to alleviate Palestinian suffering. But equally significant is the reaction by Western governments to Hamas’ 2006 election victory which seemed hypocritical to many in the Muslim world.[22] It was clear to many that while those governments encouraged democracy they rejected the choice that resulted from its exercise. Instead of acknowledging the political reality that unfolded in Palestine as the result of a democratic election, Western governments chose to turn their back on a process that they themselves had pushed to establish. Not only did they refuse to acknowledge the democratic choice made by the people; to many Palestinians, it seemed that the West was punishing them for their choice.

Canadian Policy towards Hamas

Canada lists Hamas as a terrorist organization and has no contacts with the Islamist group. Instead, Canada recognizes Fatah as the principal representative of the Palestinian people and supports Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas even though Fatah was defeated at the ballot box by Hamas. Following the results of those elections, Canada cut off ties with the Hamas-led government and refused to acknowledge it as the legitimate government of the Palestinian people. According to Canadian Foreign Minister at the time, Peter Mackay, Ottawa ceased ties because “the Palestinian government has not addressed the concerns raised by Canada and others concerning non-violence, the recognition of Israel, and acceptance of previous agreements and obligations, including the road map for peace.”[23]Interestingly, the Canadian government’s reaction came after its own observation mission to the election had put out a communiqué in which it praised the election.According to the official statement “ordinary Palestinians proved their commitment to shaping their future at the ballot box” and “the elections further promoted the culture and practice of democracy among Palestinians.”[24] The Canadian reaction to the 2006 election was in many ways similar to that of other Western governments who, as previously mentioned, failed to support the results of the democratic elections they called for.

Lessons Learned

It is now clear to most observers that Hamas is a political reality in Palestine that cannot be ignored. The Islamist group will continue to be a major player in Palestinian politics in the foreseeable future or at least as long as the conditions that facilitated its rise exist. Hamas’ recent election victory was the result of Palestinians being fed up with a corrupt Palestinian Authority combined with an absence of a political alternative other than the Islamist movement. If political trends in the Middle East are an indicator of where things are headed, Islamist movements like Hamas will continue to experience political success.

It is also clear that Canadian and International efforts to isolate the Islamist group have been counterproductive. Although Western seclusion of Hamas has weakened the group financially, it has certainly not brought it any closer to recognizing the state of Israel, accepting previous agreements or disarming. If anything, the West’s reaction to Hamas’s election victory has been a setback for democracy in the region because it tarnished the reputations of Western democratic governments that seem hypocritical in the eyes of many in the region.

Finally, what is also apparent is that Hamas, despite its continued hostility towards Israel, has shown signs of pragmatism in recent years. The participation in elections that were previously boycotted, the interest in a long term hudna (ceasefire) with Israel, and the recent halt to suicide bombings all point to the possibility of Hamas being open to political compromise. If previous groups that employed terrorism like the PLO have accepted Israel’s right to exist, then it is possible that Hamas could one day change its approach to Israel. What remains to be seen however, is whether Canada and the international community are willing and able to speed up that process of pacification.

4.2 Hizbullah

Prior to 1992, Hizbullah rejected the confessional electoral system of Lebanon, deeming it corrupt and divisive.[25] This initial policy began to erode under the influence of the charismatic pragmatist, Shaikh Muhammed Hussein Fadlallah, the spiritual leader of Hizbullah. He believed, in line with other Shi’a clerics in Lebanon, that Islamist parties should seek political engagement and compromise, working towards gradual reformation rather than the total overthrow of the secular state.[26] Some members suggested that, like the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, Hizbullah members could run for parliament as individuals but not Hizbullah representatives per se. The issue was finally resolved when Hizbullah consulted Iranian Ayatollah Khamenei, who strongly supported the participation of Hizbullah in the electoral system.[27] While this opened the door for Hizbullah participation in Lebanese confessional democracy, it simultaneously began a wave of criticisms surrounding Hizbullah’s “national identity”[28] and allegiance to the Lebanese state, owing to the fact that they had consulted the Iranian Ayatollah for the final decision on democratic participation.

The formal participation of Hizbullah in the Lebanese democratic system began in 1992, when it was elected to 12 of the 128 seats available in the Lebanese Parliament. Of these 12 seats, 8 were taken by Shi’a Hizbullah party members, while 4 were claimed by non-Shi’a parliamentarians aligned with Hizbullah.[29] In the extremely fractious party system of Lebanon, this actually rendered Hizbullah the largest parliamentary bloc in the nation. Subsequently, in 1996, Hizbullah won 10 of the 128 seats available, going on two years later to win nearly half of all municipal council seats in southern Lebanon. The decision by Hizbullah to participate in Lebanon’s democratic process may have stemmed from a change the Iranian leadership in 1989, when that country’s presidency passed from the hard-line Ali Ahkbar Mutashemi to the more moderate Hashemi Rafsanjani.[30] With backing from Rafsanjani, more radical members of Hizbullah such as Hassan Nasrallah were sidelined, leading to the triumph of pro-election figures such as Husayn Al-Mussawi. Anti-parliamentarians in Hizbullah reacted venomously to this development, with the radical Shaikh Al-Tufayli calling for the burning of voting centres and finally resigning from Hizbullah in protest.[31] Nonetheless, Hizbullah eventually settled on the common practice of transforming society and government “from below,”[32] seeking to elicit movement towards Islamist policies through grassroots support and successful political participation. This mirrored the conduct of many non-violent Islamist movements in the region, including the Islamic Action Front of Jordan, the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, and the Party of Justice and Development in Morocco.

Ideologically, the justification for Hizbullah’s democratic participation was grounded in two principles of Islamic theology: non-compulsion and social justice. Hizbullah ideologues realized that an Islamic state – modelled on the Islamic Republic of Iran – could not be imposed but instead had to be chosen by the people of Lebanon; without choice, there could be no legitimacy for such a state. This is grounded in the Qu’ranic assertion that “there can be no compulsion in religion.”[33] Similarly, it was seen as unjust to impose an Islamic state by force, as the unjust resort to force would render the resulting Islamic state illegitimate. Realizing that a state built on the Iranian model of wilayat al-faqih (“rule by clerics”) was impossible, Hizbullah pragmatically chose to participate in the democratic process, aiming to garner international and domestic legitimacy while simultaneously lobbying for its constituents in government policymaking. By 2004, Hizbullah was achieving widespread success in municipal elections, building on a record of anti-corruption and effective governance. Throughout Lebanon, Hizbullah defeated its main rival, Amal, by two to one in seats won.[34] This was achieved in part by the January 2004 German-mediated release of four hundred Palestinian and twenty-three Lebanese prisoners from Israeli jails, exchanged for an Israeli Lieutenant Colonel kidnapped by Hizbullah. Hizbullah’s large social service network also worked in the party’s favour; with a wide array of schools, lending institutions, construction companies, hospitals, and pharmacies, Hizbullah was ideally placed to garner grassroots support, especially where Lebanese government infrastructure was weak or absent.[35]

Bullets, Ballots and the Lebanese State

While Hizbullah today certainly owes a good deal of its funding and ideological support to the Iranian regime, it is nonetheless a highly nationalistic movement, seeking not to create a pan-Islamic caliphate– as Al-Qaeda and other jihadi groups do – but rather to increase the power of Shi’a Islam in Lebanon. It may therefore be categorized as what Dr. Tamara Wittes describes a “local militant Islamist movement”.[36] It may use Islamic clerics as high-ranking figures and Islamist rhetoric to “justify [its] violence,”[37] but to conceive of Hizbullah purely as an Islamist group is unhelpful. It exists in the context of the weak statehood of Lebanon, essentially functioning alongside the Lebanese infrastructure, providing basic services such as medical, financial and military institutions. This infrastructure-oriented platform, far more than Hizbullah’s use of political Islam or support of the Palestinian cause, began to garner widespread legitimacy for the group. Indeed, this fact is borne out through the broad base support which Hizbullah enjoys in Lebanon, including from secular constituents.[38] The achievement of becoming a general “vehicle for [popular] discontent”[39] thus led Hizbullah to pursue further legitimacy through the ballot box. Yet concerns remain over the power of Hizbullah to “use bullets to cancel ballots” and employ military force to “defy the rule of law”.[40] Unlike in the context of strong states such as Egypt (with its Muslim Brotherhood), paramilitary forces like Hizbullah can both participate in their fragile democracy and act as a state military. This unfortunately detracts from the unity and sovereignty of the nation itself, as sovereignty stems in part from the state’s monopoly on armed force. Hizbullah therefore exists as both a political party and the state apparatus, exemplifying its character as a “Janus-faced organization [in a] shifting political landscape”.[41] This dual character of Hizbullah is also reflected in its role as a popular resistance movement – or terror network, depending on one’s perspective – and social service provider. Hizbullah thus seeks popular legitimacy from every avenue available, working to influence, defend, and possibly become the Lebanese state (depending on the results of the upcoming June election).

The Hizbullah platform for the coming election is surprisingly conciliatory. While it still runs under the slogan of “resistance and development,”[42] it has indicated its desire for a “national unity government”[43] should it emerge victorious from the June election in Lebanon. This conciliatory stance may reflect a desire in Hizbullah to move away from divisive issues such as war with Israel. The Hizbullah-initiated 2006 conflict, while arguably a tactical victory for the movement’s guerrilla fighters, nonetheless inflicted enormous strategic-level damage on the image and territory of Hizbullah in southern Lebanon. Many Lebanese blamed Hizbullah for the disastrous conflict, and this war-weariness among Lebanese constituents may have influenced the present, more conciliatory, Hizbullah platform. The organization may also have learned from its Palestinian neighbour Hamas that elections are more easily won on the basis of non-divisive issues: anti-corruption, development, debt relief and political independence. Indeed, Hizbullah’s decision not to intervene militarily during the recent Israeli incursion into Gaza was likely based on the absence of domestic popular support for such offensive action.[44] This indicates a degree of moderation by necessity in Hizbullah, as it is forced towards a more dovish platform, naturally responding to the desires of its Lebanese constituents. This may also lead Hizbullah towards a gradual break with Iran and Syria, both of which are extremely unpopular among Lebanese nationalists, particularly secularists and non-Shi’a. Hizbullah’s increasingly broad constituency, including the aforementioned non-Shi’a ‘swing voters,’ are forcing the organization to publicly reaffirm its Lebanese nationalidentity over its Iranian sponsorship. The opponents of Hizbullah have seized upon this sensitive topic, with Saad Hariri, leader of the popular nationalist Future Movement, to declare that “victory for a Hizbullah-led coalition would accelerate the Iranian takeover of Lebanon.”[45]

Despite the moderating influence of a war-weary constituency, Hizbullah remains committed to violent opposition of Israel. Seeking to respond to the assassination of its military commander Imad Mugniyah in 2008, Hizbullah first attempted to bomb the Israeli embassy in Azerbaijan, but was disrupted by Azeri authorities.[46] A year later in January 2009, nearing the anniversary of Mugniyah’s death in Damascus, Hizbullah attempted a “massive attack” on an Israeli target in an undisclosed European nation.[47] Such an attack would have once again launched Hizbullah into the area of overseas terrorism, returning it to its early roots as an aggressive jihadi organization. The aggressive actions of Hizbullah have also endangered and divided the Lebanese state itself, demonstrating the perils of multiple military forces existing within a single state. In February 2001, during a state visit by Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri to France, where he was soliciting much-needed foreign direct investment (FDI), Hizbullah ambushed an Israeli patrol in the Shebaa Farms area. This gave rise to serious international questions over the strength and sovereignty of the Lebanese government, and indeed the stability of Lebanon more generally. Hariri described the Hizbullah ambush as a “provocation”[48] against Israel, declaring that Lebanon did not desire conflict with Israel. A serious public battle ensued, which finally had to be defused by Syrian diplomatic intervention on behalf of Hizbullah. The armed Hizbullah “struggle in the South” was, from the Syrian point of view, “not to be compromised for any reason”.[49]

The aforementioned episodes illustrate the inherent instabilities of an organization which operates by both bullet and ballot, particularly an organization with as many international links as Hizbullah. Even if Hizbullah – spurred on by the necessities of democracy – desired to permanently shift towards moderation, it is highly likely that internal hardliners and its foreign masters in Tehran and Damascus would react unfavourably. Such difficulties are unavoidable for an organization that is both militaristic and socially-conscious, Islamist and democratic, nationalistic and internationally supported. While such a group could only exist in the context of a weak, democratic state, it also maintains the very fragility in which it emerged. Hizbullah’s contending authority with the Lebanese government, in addition to its vicious reputation among Westerners, serves to de-legitimate Lebanon both internationally and domestically, thus prolonging the volatile political climate Lebanon has endured for over two decades. It remains to be seen what may result if Hizbullah takes power in the coming June elections, which 89% of Lebanese have described as “the most important in the modern history of Lebanon.”[50] A Hizbullah victory could lead to disaster and even civil war for the Lebanese state, as major international powers refuse to recognize the Hizbullah victory. Such a scenario might closely resemble the events which occurred following the democratic election of the Hamas movement in Palestine. Neither Canada nor the United States recognizes Hizbullah as a legitimate organization, and indeed membership in Hizbullah has been effectively criminalized in both states.

Canadian Policy towards Hizbullah

Until 2002, Canadian policy on Hizbullah was similar to that of many European nations, in which only the Hizbullah ‘military’ wing was banned, excluding the so-called ‘social’ wing of the movement that engages in fundraising, infrastructure, and governance. However, in December 2002, Canadian policy shifted with the addition of all of Hizbullah to Canada’s “currently listed [terrorist] entities.”[51] This shift was predicated on remarks reportedly made by Hizbullah leader Hassan Nasrallah that suicide bombings in support of the second Palestinian intifada should be “exported… worldwide”.[52] Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister Bill Graham then declared that the “humanitarian” wing of Hizbullah was no longer “distinguishing itself from terrorist activities,”[53]and should it therefore be banned in its entirety. Under intense pressure from Israeli and Jewish groups, the Liberal Martin government chose to add Hizbullah to its list of banned entities, thus criminalizing both membership and support to the organization. While Nasrallah and Hizbullah itself have traditionally been extremely supportive of the Palestinian cause, including the tactic of suicide bombing, the veracity of these particular comments proved questionable.

An investigation conducted by experienced CBC Middle East correspondent Peter MacDonald revealed that two of the three controversial quotes were “never even uttered,” while the other was a “gross mistranslation.”[54] Upon this discovery, the CBC confronted Prime Minister Martin in an interview, which, upon the broaching of the Hizbullah topic, was immediately ended by the Prime Minister. Martin later claimed that a Florida Atlantic associate professor, Walid Phares (a contributor to Daniel Pipes’ highly conservative Middle East Forum), was the source of his information on Nasrallah’s statements. This episode illustrates the difficulties inherent in assigning the label of “terrorism”; while Hizbullah has certainly carried out numerous terrorist acts during its existence, the specific trigger for the Canadian listing of the organization proved to be false. While the supposed dichotomy between the social and military wings of Hizbullah may also be rather tenuous, it is nonetheless true that the Canadian listing of Hizbullah had more to do with domestic pressures inherent in democracy, rather than an objective analysis of the group in question.

Should Hizbullah be elected to lead the Lebanese state in June 2009, Canadian policymakers will face a difficult decision. To refuse to recognize the results of elections would appear hypocritical, while accepting the results would risk a massive domestic backlash, particularly if the route of acceptance was to be chosen by a Conservative minority government. Major allies such as the United States would also be unlikely to accept such results, although this prospect may be diminished somewhat since the Democratic victory of President Obama. The creation of a national unity government in Lebanon, including Hizbullah, would only serve to further confuse Western policymakers. This eventuality would, however, improve the probability of Western recognition of such a government, although massive Israeli diplomatic pressure would be exerted across the world to prevent such an occurrence.

Lessons Learned

The rise of Hizbullah has been premised on the influence of foreign actors in Lebanon, especially through the causal role played by Israel in its various incursions into Lebanon. Iran, too, in its efforts to curb Israeli military power, has played a formative role in the genesis of the militia and populist party. Yet by examining the role and popularity of Hizbullah in Lebanon, one observes that foreign intervention and domestic militancy have by no means been popular among the Lebanese. Hizbullah’s connections to Iran and Syria have left it vulnerable to charges of disloyalty to the Lebanese state, and these charges are politically dangerous in an environment as nationalist as Lebanon. This illustrates that militants with connections to foreign states – as many armed movements possess – may often weaken domestic support for such groups. Foreign ties generate questions over sovereignty and loyalty among constituents, creating ammunition for opposition parties to target such militant organizations. This implies that militant parties with foreign ties may not be as successful in a democratic polity as compared to more domestic groups.

The Israeli influence in Lebanon has, however, contributed to the rise of popular militancy and its integration into the Lebanese democratic system. In the context of a weak state, militants will flourish so long as citizens feel threatened by outside powers with which their own government cannot contend. The popularity in Somalia of the Islamic Courts Union and its brutal Al-Shabaab (The Youth) military wing is a testament to this fact; despite despicable excesses, the Islamic fighting force represents the only genuine Somali opposition to the widely hated Ethiopian army. Hizbullah plays a similar role in Southern Lebanon, particularly after its impressive display of guerrilla warfare capabilities during the summer 2006 conflict. In order to reduce occurrences of militant or terrorist groups gaining broad popularity, it is therefore imperative for the West to guard against repeated intrusions into weak and fragile states. History provides many examples in this regard, all of which have had disastrous results for both the host country and its neighbours. Afghanistan, with its long history of resistance, terrorism, and foreign incursion, is but the most recent example of this phenomenon. If the West genuinely desires democratic movements in the Middle East which are devoid of militant tendencies, it must act strongly to safeguard peace and stability in the region, without which weak and fragile states will naturally give rise to militancy, terrorism, and the popular democratic acceptance of politically undesirable factions.

4.3 The Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood

Most scholars would agree that the Muslim brotherhood is “the world’s oldest, largest, and most influential Islamist organization.”[55] Numerous Islamist groups in the Middle East have their roots in the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, and so examining this religious, social and political movement is essential to understanding the history and context of many other movements and parties.

The Muslim Brotherhood (MB) was founded in Egypt in 1928 by Hassan al-Banna, and is described as “the first organized, formal, and thus politically relevant expression of Islamism in the modern era.”[56] The ideas of bringing Islam back to a purer state and applying shari’a law were already present in society, but the MB was the first to insist that the state should take the lead in applying shari’a, thereby “making the political act of establishing an Islamic state central to their ideology.”[57] Hassan al-Banna’s organization, however, did more than to call for the establishment of an Islamic state. The goal of the organization was to “Islamicize” society in a bottom-up process; first influencing individuals, then families, and finally society as a whole.[58] With this goal in mind, the movement provided social services to win over the hearts and minds of Egyptians, thus displaying grass-roots political activism and mobilization.[59] Politically, the MB’s religious fervor was fused with nationalism and anti-imperialist sentiment towards the omni-present British.

Scholar Israel Elad Altman has described three phases in the history of the MB. It is worthwhile to devote some time to the history of this group and their evolution over time, as it is an example of how a once violent group has been moderated. In the first period, from 1928 to 1952, Egypt was ruled by an Egyptian monarchy with a heavy-handed British presence. Al-Banna’s doctrine was elucidated during this phase, and the movement expanded beyond its lower-middle class base to include the bourgeoisie.[60] In 1948, the government dissolved the MB, and later in the year several members of the group were involved in the assassination of sitting Prime Minister al-Nagrashi.[61] Soon after, al-Banna was assassinated in retaliation, despite his condemnation of the prime minister’s assailants.[62]

The second phase, from 1952 to 1970 was marked by repression of the MB by Nasser. Nasser had an uneasy alliance with the Brotherhood in the lead-up to the 1952 military coup, but it was quickly dissolved following a botched assassination attempt on Nasser in 1954.[63] During this phase there was organizational paralysis and factionalism within the MB and rifts emerged between those who propagated the use of violent means and those who did not. As of 1954, the Muslim Brotherhood officially opted to use peaceful means to spread its message while still espousing the idea of jihad against external enemies of Islam (i.e. foreign occupation of Muslim lands). Doubting this peaceful intent, Nasser’s repression of the group continued and many of the MB’s current and future leaders languished in Egypt’s prisons, notorious for torture.[64] While some of these “second generation” leaders would later resurface with a determined commitment to peaceful means, others split from the Brotherhood to espouse a more radical and violent agenda. Of these dissidents, the most influential was the ideologue Sayyid Qutb, today described as the ‘father of modern terrorism.’[65] Qutb’s philosophy was based on the concept of takfir with which all impious Muslims could be declared apostates, and thus become legitimate targets of violence.[66] Qutb’s doctrine has inspired radical groups such as al-Jama’ah al-Islamiyyah, al-Jihad, and al-Qaeda.

The third phase of the MB, according to Altman, is that of the “Second Republic” corresponding to Nasser’s death in 1970 and Egypt’s rule by Anwar Sadat and Hosni Mubarak.[67] When Sadat came to power, he opened up space for the Brotherhood to counter the influence of the Nasserists. As a result, the MB’s influence considerably expanded in the 1970s, particularly on university campuses where they engaged and politicized a younger generation. This “second generation,” referred to as the “new Ikhwanism,” signaled a shift from the pan-Islamist orientation of the Brotherhood to strategies focusing specifically on the Egyptian state.[68] In the 1980s and early 1990s, the MB’s strategy of peaceful political participation saw the election of many of their members to Egypt’s Professional Associations, and the election of independent candidates to Parliament in 1984 (eight seats) and 1987 (35 seats).[69] The Brotherhood’s expanding influence threatened the stagnant Mubarak regime and was met with a clampdown in the early 1990s. It is noteworthy that despite intense state repression, the MB has “remained committed to a strategy of non-violent participation in formal institutional politics.”[70]

That Muslim Brothers have run for Parliament, despite having to run as independents, has forced the MB to develop a detailed and pragmatic political platform, especially in preparation for the November 2005 parliamentary elections.[71] Though still outlawed as a party, the MB ran candidates as independents, though in less than one third of all ridings to signal to that they did not seek to deny the government of the necessary two-thirds majority that is required to pass legislation.[72] Despite flagrant violations of electoral standards-including the death of 11 MB supporters, the arrest of over 700 Muslim Brothers, and ballot box stuffing-the MB still managed to win 20% of the seats (88).[73] Shockingly, the original State Department statement said that it had found “no indication that the Egyptian government isn’t interested in having peaceful, free, and fair elections.”[74]

The MB party platform calls for democracy, pluralism, human rights, the separation of power with checks and balances, and the independence of the judiciary.[75] Although critics doubt the honesty of the liberal elements of the MB candidates’ platform, the members of Parliament should be judged by their actions. In 2006, the MB-affiliated members of the national legislature spent much more of their time submitting motions on social problems (inadequate housing, decrepid hospitals, etc) and political problems (i.e. electoral fraud) than they did arguing for religious issues (although they might have proceeded with caution to avoid repression).[76] The MB has moderated its stance in pursuit of votes, and has formed alliances with secularists, nationalists, and liberals.[77]

In 2007, the MB published a draft policy platform that was detailed in its descriptions of social and economic policy, but the overshadowing element was the proposal to create a supralegislative body of senior religious scholars and the proposal that all senior posts in Egypt should only be occupied by males.[78] The proposal drew fierce criticism and was disavowed by certain MB figures “for fear of losing their democratic bona fides.”[79] The more moderate and pragmatic “second generation” leaders in the MB have emphasized that the draft is in no ways final and that there is much internal deliberation. Furthermore, one of the most influential moderate leaders of the MB, Khariat al-Shater, was in prison and undergoing a Mubarak-sanctioned military tribunal at the time of the publication, allowing the conservative elements more influence.[80] The MB’s platform is at odds with certain aspects of the Western liberal democratic model. However, the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood’s transition in the past two decades from a pan-Islamist movement to movement whose primary focus is on state-bound politics should not be underestimated, as it has influenced other MB branches across the Middle East and North Africa to do the same.

Finally, some critics accuse the Brotherhood of radicalizing youth in the Middle East and Europe, but they are far less radical than many other groups. One senior member of the MB’s Guidance Council in Egypt has described the MB as a “safety valve for moderate Islam” without which many more youth would have chosen to become involved with violent groups.[81] It is also noteworthy that the Egyptian MB is disdained by radical groups for their moderation and their willingness to make political compromises.

Canadian policy makers must urgently realize that the political development of moderate Islamist groups, such as the Muslim Brotherhood, is in the national interest, and the best interest of the region. The MB has a strong base of support in Egypt, and a failure to make progress in the political realm could discredit their peaceful means and embolden more radical and violent groups.[82]

Canadian Policy

In theory, Canada is committed to democratic good governance in the Middle East and North Africa. Through CIDA, the Canadian government supports the Office for Democratic Governance whose mandate is to “promote freedom and democracy, human rights, the rule of law and open and accountable public institutions in developing countries.”[83] Within this office, there is a specialized program called the Middle East and North Africa Good Governance for Development Program (2008-2011), and also funding for the IDRC’s Middle East Good Governance Fund to increase policy relevant knowledge about Islamist parties in general, and about the of integration into the political system on the moderation of a party’s views.

Human rights are also listed as a value to which the Canadian government is deeply committed. According to the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, “the Canadian government has identified democracy as one of four core values that guide our foreign policy, along with freedom, human rights and the rule of law.”[84] However, despite a spoken commitment to these values, there has been a lack of political will to put words into action in the Middle East. The priorities in Canada’s relationship with Egypt appear to be trade and regional stability, without sufficient regard for democratic governance and human rights.[85]

Though Canada has made public statements about human rights violations elsewhere in the world, in Egypt (and the broader Middle East in general), human rights violations fall upon deaf Canadian ears. According to Human Rights Watch, in the third round of the 2005 November/December Parliamentary elections in Egypt, over 1600 political activists were arrested, at least 700 of whom were supporters of the independent candidates running on behalf of the Muslim Brotherhood.[86] In addition to these arrests, 11 MB supporters were killed when police fired into a crowd; security forces prevented voters from reaching the polls (some voters being chased away by NDP thugs with machetes and knives as the police looked on), election observers were denied the right to enter the polling stations, let alone observe the count, and other flagrant and widespread electoral manipulation. The Canadian government made no public comment on these violations of human rights.

The United States and several European governments have at times put pressure on Mubarak to release various members of the secular opposition. The most noteworthy case has been with the presidential opposition candidate Ayman Nour, who has been arrested several times. At times, the pressure from the West has paid off. For instance, in early 2004 the Bush administration cancelled an official visit to Egypt by Secretary of State Condeleeza Rise in response to Nour’s jailing.[87] This pressure was effective in securing his (temporary) release. However, the United States’ approach has been limited and inconsistent: limited to lobbying on behalf of the secular “westernized” individuals, while remaining silent regarding the fate of others who have been unjustly imprisoned (i.e. candidates and supporters who are linked to the MB).

To date, the failure of Canada and other Western powers to engage with the Muslim Brotherhood is not a subject that receives much attention. However, in the future, it will be increasingly important to build relationships with moderate groups, such as the Muslim Brotherhood, if the West is indeed going to push for political openings in the Middle East. Parties like the Muslim Brotherhood should be seen as potential partners; not as adversaries.

Lessons Learned

The Muslim Brotherhood enjoys significant popularity in Egypt and despite the Mubarak regime’s efforts to suppress the movement its popularity continues to rise. Even while being denied the opportunity to officially contest elections as a political party the Brotherhood continues to engage in Egyptian politics peacefully by fielding candidates as independents. Like Hamas, Hezbollah and other Islamists in the region, the Brotherhood are popular because they are seen to represent an alternative to a failed status quo. The West’s continued support for Mubarak in spite of his regime’s poor human rights record is a continuation of a long term Western policy of supporting regimes in the region that are seen as buffers against Islamist movements. This is why there has been little reaction by Western governments during the 2005 election to the Egyptian regime’s flagrant electoral violations. The long term risk is that, in the eyes of many, the West’s lack of action against such violations will only weaken its case against similar violations in places like Zimbabwe. If Western democracy support is viewed by people in places like Egypt only as a tool to advance Western interests then it is likely to have negative consequences for democracy in the region. Moreover, if groups like the Brotherhood that renounce violence are denied their rights then it only makes it harder to convince violent groups to give up their arms. By working with and further encouraging the Brotherhood to continue engaging in the political process, the West could send a powerful message to other groups in the region that more can be achieved through the ballot box than with bullets.

The Canadian government shares certain values and goals with parties that oppose Mubarak’s autocratic regime, above all, that of democracy. A shared commitment to democracy is the common platform on which Canada can begin to engage with Islamist opposition to the Egyptian government, in particular, the Muslim Brotherhood. As Stacher recommends:

“This does not mean that the Muslim Brotherhood should be given preferential treatment by European or North American governments. It simply reflects the fact that political reform in Egypt and the wider region will not progress if the mainstream Islamist movements are excluded from the process.”[88]

As Canada considers its policies in the broader Middle East and North Africa region, the beginning of wisdom is, as scholar Daniel Blumberg has suggested, that Islam is not the unequivocal answer to the region’s problems, but nor is it the problem.[89]

5. Conclusion: Policy Recommendations

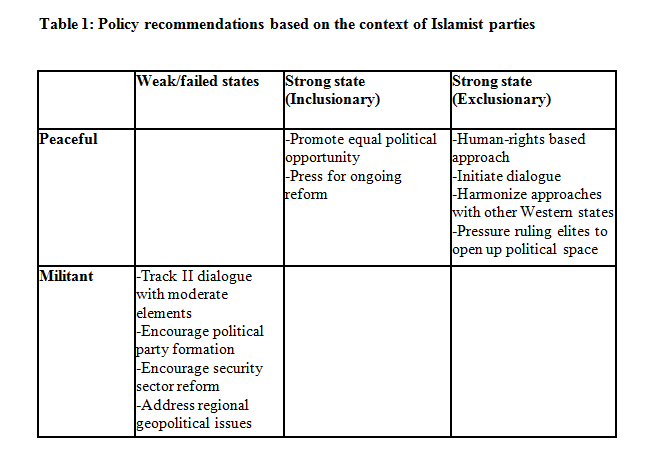

By examining the cases of Hamas, Hizbullah, and the Muslim Brotherhood, it becomes apparent that not all Islamist parties are alike and that understanding their histories and differences is essential for Western policy makers with an eye on the Middle East. As mentioned in section 3, Islamist groups are best differentiated by the context in which they operate, and so we turn back to that framework to inform our policy recommendations.

In strong exclusionary states, such as Egypt, we recommend that the Canadian government take a stronger stand towards autocrats that severely limit individual freedoms and human rights. This could begin with public statements decrying human rights abuses in exclusionary and repressive states. However, if human rights are truly to be understood as universal, they should not just be tools to protect our friends and allies. In other words, if human rights complaints are only made on behalf of our ideological allies (or as close as they come), then we corrupt the concept of “universal” human rights by only supporting them as long as it is in line with our interests. Such has been the case of the United States’ lobbying for the release from prison of Ayman Nour while simultaneously ignoring the plight of other prisoners of conscience with a religious profile (such as some 700 MB members arrested during the 2005 elections). If human rights are not applied consistently and universally, those excluded will have every right to be skeptical that the “human rights” discourse is Euro-centric and a guise for interest-oriented politics.

Although we did not examine any Islamist parties in strong inclusionary states, these groups deserve at least minimal mention. It is important in cases such as Morocco and Kuwait that Western leaders continue to nudge the leaders of these states to continue unscrewing the hinges and further opening up political channels. Peaceful Islamist parties in these states have generally demonstrated pragmatism and maturity, and progress that they make could be pivotal as examples of what can be peacefully achieved through the democratic process.

In the case of weak and failed states, our two case studies of Hamas and Hizbullah demonstrate that considerable nuance is needed even within this category. We recommend that assistance be provided to help to encourage political party reform. A larger and more long-term topic that must be addressed is how to go about security sector reform in states where instability provides an incentive for Islamist and other groups to arm to defend themselves. Canadian policymakers should reference the growing body of conflict management literature that addresses security sector reform, including third party guarantees, and coordinate efforts with other states and multilateral institutions. These recommendations are summarized in Table 1.

No discussion of Middle Eastern politics is complete without mention of the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict and its negative impact on the region. Anyone with an understanding of the region’s history and politics understands that a just and comprehensive solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is the cornerstone of all relations in the Middle East. Even if that can not be envisioned in the immediate future, Canada must engage and develop a nuanced, less one-sided approach that can aid in the resolution of this conflict and pave the way for constructive Canadian relationships in the Middle East. In recent years, Canada has unconditionally supported Israel, and this has been detrimental to Canada’s reputation in the region. In the long run, unconditional support of Israel by any Western state only creates another obstacle to peace in the region, and therefore hurts both Palestinians and Israelis.

Finally, consider this quote:

“The spread of regional violence unfortunately has greatly strengthened the voice of the radicals against the moderates, especially when the moderates seemingly cannot demonstrate that their peaceful path has borne fruit…”[90]

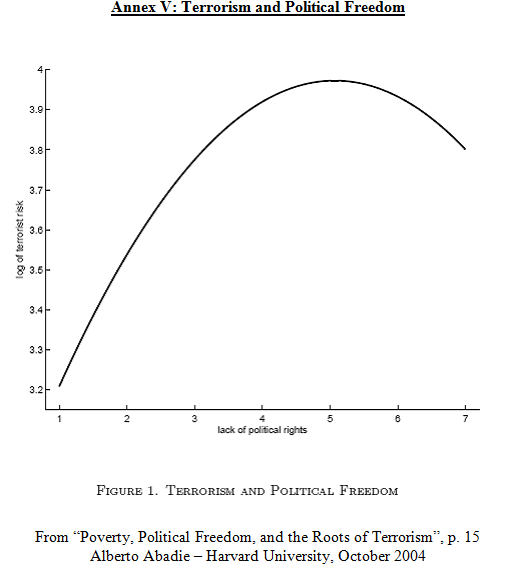

It is in the Canadian interest and the interest of the Middle East in general that radicals are not empowered by the frustratingly slow progress of democratization. It has been empirically demonstrated that the lack of political rights is positively correlated with the risk of extremist terrorism, whereas high levels of political enfranchisement result in a low risk of terrorism (see Annex III). On these grounds, Canada should take the first steps to engage in a limited dialogue with peaceful opposition parties and candidates, including those representing the MB; doing so will prevent the rise of groups that operate strictly by the “bullet” rather than the more peaceful “ballot”. The engagement that we propose need not entail high level talks. Many Islamist parties, (and others, for that matter), are wary of being branded as Western pawns and have little interest in meeting with any Western government or organization that is seen as contributing to the region’s problems.[91] What we propose is that channels are opened between Canadian diplomats and members of the MB, and potentially with the political wings of Hamas and Hizbullah. In exclusionary states, Canada must work in tandem with other Western governments to apply consistent pressure to open up political channels for other actors to have a voice in governing. In weak states, the Canadian government should, with other partners, seek out incentives that can be provided so that militant parties will disarm.

So far, the European embassies have had some very limited contact with a few senior members of the Muslim Brotherhood and the US embassy has met with the head of the group’s Parliamentary bloc but have been discouraged with meeting with other members of the group (since it is outlawed).[92] To the surprise of its allies, the British Foreign Office has recently initiated Track II dialogue with Hizbullah, cultivating “carefully selected” contacts with the “political wing” of the organization.[93] Canada should follow these timid steps, but with somewhat more confidence, focusing especially on peaceful Islamist organizations as opposed to violent groups. For example, by not meeting with members of the MB, Western diplomats are implicitly respecting Mubarak’s state of emergency laws under which all groups of religious affiliation are banned. While the brutal authoritarianism of states such as Egypt may temporarily abate the risk of terrorism, it is clearly evident that peace and democracy are compatible, as the lowest levels violence can only be attained in a human rights-oriented state (see Annex III). Canada and the West should therefore take the role of strong advocates for universal human and political rights, as enshrined in the ideal of democracy of the numerous conventions and norms of international law. While this may entail temporary diplomatic and political costs, it is ultimately the only approach which may ameliorate the twin dilemmas of authoritarianism and terrorism in the Middle-East.

1 Knudsen (2002)

2 Ibid

3 Esposito and Voll (2001)

4 Ibid

5 Abootalebi (1991)

6 Carroll (2004)

7 Esposito and Voll (2001)

[2] Leiken and Brooke (2007), 112

[3] Dunne (2009), 140

[4] Masoud (2008)

[5] Hamzawy and Brown (2008), 50

[6] Ibid

[7] Ibid

[8] Masoud (2008), 21

[9] Hamzawy and Brown (2008), 51

[10] Ibid, 52

[11] Council on Foreign Relations, “Hamas” (7 Jan 2009)

[12] Ibid

[13] Westcott, “Who are Hamas?” (19 Oct 2000)

[14] Ibid

[15] Ibid

[16] Higgins (2009)

[17] Ibid

[18] Anti Defamation League, (2006)

[19] Pina (2006)

[20] Halevi (2004)

[21] Ottawa (2006)

[22] LaFranchi (2006)

[23] Labott (2006)

[24] Statement of Preliminary Findings and Conclusions — Palestinian Legislative Council Elections (2006)

[25] Norton (2007), 98

[26] Norton (2007), 99

[27] Ibid, 100

[28] Ibid

[29] Saad-Ghorayeb (2002), 46

[30] Ibid, 47

[31] Saad-Ghorayeb (2002), 47

[32]Cofman Wittes (2008), 9

[33] Qu’ran, 2:256.

[34] Norton (2007), 107

[35] Ibid, 109

[36] Coffman Wittes (2008), 8

[37] Ibid

[38] Coffman Wittes (2008), 11

[39] Ibid, 11

[40] Ibid, 8

[41] Norton (2007), 45

[42] Lamb (5 March 2005)

[43] Ibid

[44] Berti (2009)

[45] Lamb (2009), 2

[46] “Massive Hizbullah attack against Israeli target thwarted in Europe”, Haaretz, January 29, 2009. http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/1059589.html.

[47] Ibid

[48] Harik (2004), 152

[49] Ibid, 154

[50] Lamb (2009), 1

[51] Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada. “Currently Listed Entities”. http://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/prg/ns/le/cle-eng.aspx.

[52] Parry (2006)

[53] Ibid

[54] Ibid

[55] Leikien and Brooke (2007), 107

[56] Haqqani and Fradkin (2008), 14

[57] Ibid

[58] Leikin and Brooke (2007), 108

[59] Leiken and Brooke (2007), 108

[60] Altman (2009), 8

[61] Stacher (2008), 10

[62] Leiken and Brooke (2007), 108

[63] Stacher (2008), 10

[64] Altman (2009), 19

[65] Stacher (2008), 11

[66] Leiken and Brooke (2007), 110

[67] Altman (2009), 12

[68] Ibid, 8

[69] Stacher (2008), 11

[70] Stacher (2008), 12

[71] Dunne (2009), 134

[72] Altman (2009), 15

[73] “Voter disenfranchisement and Arrests Dominate the Election Day,” Independent Committee on Election Monitoring (ICEM), December 1, 2005

[74] Traub (2008), 131

[75] Ibid, 11

[76] Masoud (2008), 23

[77] Leiken and Brooke (2008), 110

[78] Hamzawy and Brown (2008), 54

[79] Cofman Wittes (2008), 10

[80] Stacher (2008), 20

[81] Stacher (2008), 12

[82] Cofman Wittes (2008), 12

[83] CIDA website

[84] DFAIT: http://www.international.gc.ca/glynberry/transitions.aspx?menu_id=7&menu=R

[85] Canadian embassy in Egypt: http://www.international.gc.ca/missions/egypt-egypte/bilateral-relations-bilaterales/menu-eng.asp

[86] Malinowski and Stork (2005)

[87] Traub (2008)

[88] Traub (2008), 26

[89] Daniel Brumberg, (2005/2006)

[90] Fuller (2005), 47

[91] Stacher (2008), 25

[92] Stacher (2008), 25

[93] Lander (2009)

—

Written by: Omar Alihashi, Anna Gruending, and Paul Knight

Written at: Carleton University

Written for: Prof. Bob Miller

Date written: 2009

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Middle East: An Orientalist Creation

- China’s Increasing Influence in the Middle East

- Women at War in the Middle East: Gendered Dynamics of ISIS and the Kurdish YPJ

- The Instrumentalization of Energy and Arms Sales in Russia’s Middle East Policy

- (Re)Shaping Territories to Identities: Is the Middle East a Colonial Invention?

- Promoting Democracy in Serbia — The Limits of EU Conditionality