This paper examines the discourses within the British media following the 2008 financial crisis. The renewed interest in the writings of John Maynard Keynes had been heralded by some commentators as a paradigm shift in economic thought. Genuine Keynesian theory places an emphasis on the social nature of market transactions in which uncertainty and liquidity are intrinsic to economic behaviour.

The paper argues that rather than a Keynesian revolution, British thinking was dominated by ‘New Interventionism’; this conceived of the crisis as temporary contractions in consumer demand and credit lines. Policies such as fiscal stimulus and quantitative easing emerged as ad hoc solutions and retained a faith in efficient market theory.

The author conceptualized economic policies as being based on either Keynesian theory or efficient market theory. A content analysis was applied to newsprint articles from six British newspapers and used to systematically categorize the policies discussed. It is argued that attitudes towards capital controls, the global trade system, fiscal policy and monetary policy predominately retained a faith in efficient market theory.

The author then provided a constructivist account of the role of fiscal balance and price stability within British political discourse and institutions since the 1970s. A critical discourse framework was devised and applied to the media discourse. This served to demonstrate that policies such as fiscal stimulus and quantitative easing were being represented in a manner which accentuated the risks associated with inflation and public debt. In such a way fiscal balance and price stability were reinforced as regulatory rules and norms of purportedly ‘good’ economic governance. The paper concludes that the media discourse did not contain a significant re-evaluation of economic governance in contemporary Britain.

-1 Introduction-

In 2004, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, Ben Bernanke, described the global economy as exhibiting ‘a remarkable…decline in macroeconomic volatility.’ This era was being dubbed ‘The Great Moderation’, due to low inflation and low output. As this confidence became more widespread, the global economy featured a lower regard for liquid assets, and a tendency towards borrowing in order to lend. A property bubble in Britain supported a society of high consumerism and high indebtedness. In 2008, this serene picture altered. The collapse of the property bubble led to a virtual freeze of the credit system. The effects of this on Britain’s levels of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) were instant. GDP fell by 0.6% in the third quarter of 2008. Just three months later levels had fallen by a further 1.5%.[1]

The aftermath of the crisis has seen mainstream economic opinion formers publicly question the free-market capitalist model. In March 2008, Josef Ackermann, chief executive of Deutsche Bank, was quoted in the Financial Times as saying “I no longer believe in the market’s self-healing power.” The influential Economist Robert Shiller began advocating robust government intervention to tackle the crisis, specifically citing the twentieth century British economist, John Maynard Keynes.

For policy makers, ‘Keynesian’ solutions, such as fiscal stimulus and far reaching state intervention, resurfaced as the most viable option for shielding their citizens from market forces.

In a recent article, David Hudson described the new found interest in Keynes and government economic management as ‘New Interventionism.’ Hudson was labelling ‘a default policy position’, replete with a renewed faith in the efficiency and rationality of free-market capitalism (Hudson; 2009; 4).

This paper will assess the view that there has been no serious intellectual challenge to the neo-liberal model of capitalism in Great Britain. It will be argued that the discussion of policy instruments in the British media did not recommend a return to mixed-market economies. It identifies price stability and fiscal balance as organizing principles of British economic policy and argues that the British newspaper press reinforce these principles through their representation of the risks associated with inflationary policies and public borrowing.

-2 Characterizing Economic Policy-

2.1. Efficient market theory and the logic of the market

During ‘The Great Moderation’, the political organization of western capitalist states hinged on a libertarian axis of individual rights and freedom of choice (Woods; 1995; 162). The economic school of Efficient Market Theory (EMT) has been inseparable from this political movement because it advocates minimal governance (Toye; 1992; 15) and, as a consequence, the primacy of individual decision making (Best; 2008; 365).

The public policy recommendations of EMT are the logical consequences of three economic assumptions. These assumptions are explanations of individuals’ ability to predict the future, individuals’ attitudes towards money, and individuals’ consumption decisions. These three assumptions are;

(1)The future: EMT is founded on the premise that outcomes associated with a future date can be reliably predicted by statistical analyses of past and present data (Davidson 2007(a); 33).

(2)The neutrality of money; EMT assumes that money is nothing more than a unit of exchange. Therefore, changes in the quantity of money in an economy will not have an effect on the aggregate level of employment and production in that economy.

(3) Consumer decisions; Following EMT, each consumer product is assumed to act as a satisfactory substitute for every other product. Consequently, people base their consumption decisions on relative prices and will purchase more of the comparatively cheaper product, whilst spending the same total amount of income. Price (and wage) reductions will lead to the use of previously under consumed resources (Davidson; 2007(a); 30).

On this account of human behaviour, the market place will optimally allocate capital towards lucrative projects, as long as participants are able to base their decisions on reliable information about the future (Davidson; 2007(b); 13). Secondly, it is non-monetary factors, such as level of wages or prices, which effect output and employment (Davidson; 2007(a); 27). Finally, flexible wages and prices will lead to the efficient allocation of labour and consumer goods. Consequently, the neo-liberal capitalism model has been one of a minimal state, encouraging the private sector and the free movement of people and capital (Woods; 1995; 162).

2.2 .The challenge posed by Keynesian theory

Economic historians support Hudson’s intuition that that a genuine shift towards Keynesian thinking would require a deep reassessment of the economy (Davidson, 2007(a); Best, 2004; Salant, 1989; Colander & Landreth ,1997; Skidelsky, 2000; Boughton 2002). Studies of Keynes’ contribution to economic theory are at pains to emphasize that his theorizing was fundamentally different to the mainstream economists of both his and the modern era (Salant; 1989; 30).

In his General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Keynes produced a ‘revolutionary’ analysis of monetary economics, which rejected the aforementioned three axioms of classical economics (Davidson, 2007(a); 23). Keynes doubted that these assumptions were applicable to an economy in which most industries were privately managed by entrepreneurs (Davidson; 2007(a); 43). Keynes’ dissent was based on his conceptions of people’s attitude towards both the future and money itself.

Animal Spirits

Keynes’ work on probability (1921) and his discussion of investment in The General Theory (1936) reject economic theories which are based on the assumption that present information can be used to calculate the probability of future market outcomes. Keynes explained that ‘knowledge for estimating the future yield of investment amounts to little and sometimes nothing’ (Keynes; 1936; 149-50).[2] For Keynes, entrepreneurs recognize that future market conditions are unpredictable. Consequently investment spending by entrepreneurs is not guided by sound reasoning but irrational ‘animal spirits.’

A Keynesian notion of uncertainty undermines EMT’s assumption that unregulated financial markets can optimally allocate funds to the most profitable investment opportunities.

Keynesian thought rejects the rationale behind liberalizing labour and product markets because it does not accept that flexible wages and prices alone will provide full employment of labour and capital (Davidson; 2007(a); 34).

The Poet of Money

Michael Lawlor traced Keynes’ intellectual development to the Cambridge tradition of Monetarist economics (Lawlor; 2006; Chapter 12). Keynes broke from this orthodoxy in Chapter Seventeen of the General Theory (Keynes; 1936; 230-233).

For Keynes, money has an intrinsic quality as a store of value because it can be quickly and readily used to buy goods and settle debts and contracts (Davidson; 2007(a); 49). The unpredictability of the future will motivate agents to hoard money rather than immediately use it for exchange.

Savings provide security and this assurance entails that saving is not merely a decision to postpone further consumption. This has consequences for employment in an economy.

Money is fundamentally different to other assets and is not produced just to satisfy demand. Increasing the price of money does not make less liquid assets, such as houses, an attractive substitute. This undermines the gross substitution axiom of EMT (Davidson; 2007(a); 52).

In addition to this, there is no tendency to substitute some other product for money. This means that money is not produced by the private sector and a change in demand for this asset will not instigate a shift in employment across sectors to meet this new demand (Lawlor; 2006; 268).

Keynes’s world view led him to prescribe a permanent role for government to correct the faults of the entrepreneurial system (Davidson; 2007(a); 30). For Keynes, the economy had a social purpose, to provide for the material security for all participants (Keynes; 1930). Discretionary fiscal policy was to be the prime instrument for managing the aggregate demand necessary to sustain full employment (Congdon; 1978; 83).

2.3. Policy paradigms

Previous studies of changes in economic policy in the UK provide a clear analytical framework for assessing the current period. Peter Hall should be considered to be the leading scholar of British Keynesian policy. He has contributed both a comparative study of the adoption of Keynesianism in the Britain and France (1986), and an account of the subsequent shift in British policy from Keynesianism towards Monetarism (Hall; 1993).

Hall’s most influential work is an anthology of studies of demand management and deficit financing (1989). This project encompassed a much broader selection of countries and polities (Hall; 1989). In this volume, Hall introduced the analytical tool of a ‘policy paradigm.’ This explained the variations and similarities Hall observed in the cross-national implementation of Keynesian demand management.

Hall’s ‘policy paradigms’ are standards which dictate policy choices made on three levels:

First order: specific level of (i.e. level of tax). A change here is routine and incremental.

Second order: policy instrument (i.e. a new form of taxation). This is a more strategic change.

Third order: teleology or purpose of economic policy making (i.e. eradication of poverty). A change at this level is to be considered the most radical shift in thought.

The ‘second order’ shift, a change in policy instruments, is considered to be ‘normal’ policy making (Hall; 1993; 288). Such changes are located within ‘the state’, that is to say the Treasury and Bank of England, and do not necessarily entail a more radical ‘third order’ change.

Hall’s threefold formulation is appropriate for my enquiry because it provides a neat conceptual framework to assess current policy change. The view under assessment is that;

Current economic policy making is exhibiting a ‘normal’ period with changes in instruments and levels, rather than exhibiting a third order shift in the guiding principles of policy.

2.4. Britain’s Radical Shift

Hall found that no single political or economic event could explain how Monetarism took hold over policy making in Britain in the 1970s (Hall; 1993; 284). The spending programmes employed by the British government to combat a global recession in 1973 released inflationary pressures into the domestic economy (Hall; 1986; 94). Two years later inflation was at 25% and the rising cost of living was the fundamental political issue of the day (Tomlinson; 1990; 298). It was to be another four years before the shift would be complete with change both teleology and policy instruments in 1979 (Hall; 1993; 287-288).

The intermingling of ideas through political parties, bureaucracy, think-tanks, media and financial institutions led Hall to characterize the ‘third order’ change as a sociological shift within wider society. This period featured a high volume of sophisticated economic debate in the press. In particular, the newspaper industry emerged as proponents of monetarist explanations for the causes of inflation, the stability of the private economy and the ability to sustain employment through fiscal policy (Hall; 1993; 284).

This suggests a study of the economic ideas in wider society. The techniques for this have been most developed in sociology and social constructivism and I will now provide a discussion of the insights constructivism can provide for my study.

-3 Locating the organizing principles of British political economy-

3.1.1 Constructivism

Constructivism is an analytic framework rather than a ‘grand theory’ of international relations (Reus-Smith; 2009; 226). On constructivist ontology, state actions and interests are shaped by shared ideas and understandings (Chwieroth; 2003; 4). The approach studies ideas about interests and the dissemination of ideas (Wendt; 1999). In this way, constructivism engages with Amartya Sen’s point that individuals’ decisions are based on a wide base of economic, cultural and political information, not to mention psychological conditioning (Sen; 1999; 62). Constructivists are ‘structurationists’ because they hold that although non-material structures, (ideas), shape the identity and interests of actors, simultaneously actors’ practices maintain and transform those structures (Reus- Smit:2009; 221).

For constructivists, political and economic institutions are the shared ideas that confer status on particular roles and attach significance to actions and events (Searle; 1995). Rather than relying on an outside event, such as a financial crisis, to ‘clear the way’ for new patterns of behaviour (Sheingate; 2003; 186), constructivist approaches situate mechanisms for change in the existing tensions within a society. Institutional change of some degree occurs when agents’ perceptions of the world alter. This captures way in which ideas reinterpret institutions, their role within institutions, and the extent to which these ideas are distributed, reinforced or modified (Wendt; 1999; 119). There are many meta debates within constructivism as to whether ideas or material interests should be given primacy in a causal explanation.[3] To clarify which specific brand of constructivism I draw upon, it is useful to adopt a categorization from David Marsh. This paper is firmly ‘additive’, in the sense that I provide ‘no real discussion or theorisation of the relationship between the material and the ideational’ (Marsh; 2009; 684).

Traditionally the constructivist approach has been more established amongst International Relations (IR) theorists than political economists (Ruggie; 1998). Cohen (2007) attributes this to the professional preferences of economists for neat, testable hypotheses. This should be considered an academic loss (Woods; 1995).

3.12 Principles of organization

John Ruggie (1998; 684) and Benjamin Cohen (2008;131-133) cite Peter Katzenstein’s approach to IR as being particularly important for International Political Economy (IPE) scholarship. In The Culture of National Security, Katzenstein (1996) examined the ways in which normative beliefs and institutional ideas, such as the military, become integrated within a national identity. Such an approach allows one to individuate the organizing principles of a society and identify the ideas that would have to alter in order to instigate major societal change (Ruggie; 1998; 684). This should be considered to be valuable, because it promises to provide a means for locating potential sources of change, generating predictions and empirically testable hypotheses (Reus-Smit; 2009; 219). This paper therefore follows Katzenstein in its theorizing of organizing principles.

For example, in The Great Transformation, Karl Polanyi argued that Keynesian mixed market economies were a response to the demands of the sections of society most threatened by unregulated capitalism. Polanyi concluded that this political process terminated with mixed market economies. For Polanyi, income redistribution and limits on capital became the organizing principles of industrialized nations (Polanyi; 1944; 71).

Economic historians provide evidence that this era was one of unparalleled growth (Davidson; 2007(a); 95). By 1960, countries employing expansionary fiscal policy contributed in excess of 70% of the gross world output and nearly 80% of the world’s value added in manufacturing (Hobsbawm; 1994; 205). Transnational trade proportions increased (Krasner; 1976; 331-332). During the period 1945-1970, the USA quadrupled its exports to the rest of the world (Hobsbawm; 1994; 277). In spite of 25 years of apparent prosperity, by the mid seventies the Keynesian model was perceived to have failed. It seems difficult to explain how this move away from Keynesianism was in the interests of nations, workers employed in manufacture, consumers or industrialists.

Mark Blyth has consistently championed a constructivist approach to IPE (1997; 2002; 2003(b); 2007(b)). He argues that the death of the mixed-market has a straightforward explanation; the process through which market forces support and antagonize communities is fluctuating and complex. The important dynamic is for there to be a group which perceives itself to benefit from contesting the organizing principles of an institution.

Blyth provides an account of how business groups perceived themselves to be threatened by government economic management. Consequently, in America, Keynesian demand management was rejected in favour of monetarist economics through a ‘constructed crisis’, rather than an exogenous event (Blyth; 2002; 6).

In the 1970s the top eight OECD economies experienced moderately high levels of inflation[4], yet this state of affairs became to be viewed as a ‘crisis’ facing society. Inflation specifically injures only a small section of society, those who rely on stable prices and returns on financial assets.

Blyth focused on the way in which business interests launched a campaign through think-tanks, media and political parties in America (Blyth; 2002; 152-166). Following this campaign, American society shared businesses’ aversion to inflation. In this way, inflation aversion was constructed as the organizing principle of economic policies and institutions. It is the study of institutionalized inflation aversion that provides much of the focus for my study.

An important conceptual point is generated by the economic literature. Fiscal stimuli require large levels of public borrowing and have inflationary consequences. A review of recent economic history and academic economic studies produced between 1976 and 1997 provides evidence for the view that fiscal balance and price stability (inflation targeting) should be considered organizing principles of British political economy. In such a way, this paper follows Katzenstein by taking a ‘unit-level’ analysis; I am focusing on ‘institutionalized regulatory and constitutive national social and legal norms’ (Reus-Smit; 2009; 224).

3.2. ‘Sound Finance’: The Organizing Principles of British Political Economy

3.2.1. Fiscal Balance.

The significance of fiscal balance can be traced through recent economic history. This principle had its roots in the ad hoc policy reactions to a balance of payments problem. This developed into a public debate and later culminated in an institutionalization of fiscal balancing.

The literature supports the view that the period 1973-1980 was one in which the public were introduced to the desirability of fiscal balancing. Keynesian demand management led to a large balance of payments deficit (Hall; 1986). A mismanaged exchange rate devaluation prompted the government to apply for IMF support in 1976, a course of action usually taken by ‘third world nations’ (Krugman; 1994; 172). In 1976 the UK government published monetary supply targets and publically prioritized a reduction of public borrowing ahead of social spending (Thain; 1985; 263).

Arguments concerning the size of the public debt gained further exposure in the 1979 General Election. Margaret Thatcher was elected with a message thatthe large budget deficits accrued by labour governments were associated with higher taxation. This, Thatcher argued, reduced investment by taxing interest earned (Krugman;1994;170) and ultimately diverted savings away from real investment which could potentially raise productivity (Hall;1986;101). Once elected, the new administration set a 5 year target to reduce borrowing as a percentage of GDP from 4.75% to 1.5% [5]

A final theme from the literature was that fiscal balance had an instrumental role as an organizing principle. Accounts written by policy advisors during the implementation of the Medium Term Financial Strategy indicate that policy makers viewed fiscal balance as a means to support monetary control (Thain,1985; Congdon, 1978). It supported monetary control by convincing financial markets that targeting inflation was the government’s main policy objective (Thain; 1985 ; 268).

Even when the government could not accomplish this objective through restricting spending, it was supported through privatization revenue (Congdon; 2007; 96). In this way, establishing a ‘credible’ commitment to fiscal balance was considered to be more important than the choice of policy instruments (Thain;1985).

The desirability of fiscal balance was reinforced explicitly by two recent Chancellors of the Exchequer. In 1988, Conservative Chancellor Nigel Lawson’s budget speech described the public sector borrowing target as’ a norm.’ Even when Labour regained legislative power in 1997, the new Chancellor, Gordon Brown, reinforced this ‘norm’ by announcing specific rules on borrowing limits (Hay; 2005; 9).

3.2.2. Price Stability

Similarly the principle of price stability through inflation targeting can be traced through studies of recent British economic history.

Firstly, the public were introduced to the benefits of anti-inflationary policy. Initially, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) imposed monetary targets on Britain in 1976 (Michie; 1992; 196) and this demonstrated a lesson in the ‘correct’ way to manage the economy.

The 1979 General election served to keep inflation at the forefront of debate. In the year 1979-1980 inflation rose from 14.5% to 19.9% (Toye; 1992; 15). Milton Friedman’s argument that inflation carries real economic costs was a fundamental part of the monetarist economics advocated by British Conservatives (Toye;1992 ;12). Freidman (1968) successfully predicted that both inflation and unemployment would incrementally rise and provided a basis for the view that only a moderate rate of inflation would keep unemployment low (Krugman;1994;45). Later, the anti-inflation arguments used to win votes became legitimized as putative ‘facts’ by Monetarist research institutes such as the Centre for Policy Studies (Blyth; 1997;235).

One can chart this popularization of inflation aversion into a legal institutionalization of inflation targeting. During the period 1990-1992, Britain adopted the policy of shadowing German interest rates. In her study of European Monetary Union, Kathleen McNamara argues that during this period, the German exemplar, which experienced low inflation and high employment, was attributed to the policies of the Bundesbank (McNamara; 1998). In this way one can see an attempt to target inflation. In the wake of the 1992 breakdown of the Exchange Rate Mechanism, policy makers had several possible monetary targets available to them, such as such as price level or nominal GDP (Cukierman;1994;1437). However, UK monetary authorities moved to inflation targeting in October of the same year (Mihailov; 2005; 3).

The institutionalization was complete in 1997 when The Bank of England was granted formal operational independence from the UK treasury. This move cemented New Labour’s anti-inflationary credentials (Hay; 2005;6). This institutionalization is epitomized by the new-convention that the governor of the Bank of England is bound to explain in writing a failure to restrict inflation to within one point of the government’s inflation target.

Studying the research available to policy makers in the years preceding the Bank of England’s independence leads one to conclude that inflation targeting was the organizing principle of the policy. In particular, the intellectual climate prior to 1997 was conceptually synthesizing the issue of Central bank independence with the issue of inflation targeting. Contemporary empirical research by Alessina and Summers (1993) reported a negative relation between inflation and degree of legal independence. Some authors, such as Cukierman, defined degree of central bank independence in terms of the extent to which a central bank had been assigned low inflation as its sole purpose (Fischer; 1995; 203). Posen (1993) argued that inflation adverse countries, those with politically powerful financial sectors, such as Germany and Switzerland, developed the institutions to support this aversion.

With this information, the investigation needs to look not just at policy recommendations, but also at the presence or absence of the principles of price stability and fiscal balance. After all, if ‘New Interventionist’ policies such as fiscal stimuli and quantitative easing are inflationary and require high levels of borrowing, it is reasonable to expect that the organizing principles of ‘sound money’ would be challenged in the discourse.

3.2.3 Representation

This paper focuses on organizing principles through an IR constructivist approach, focusing on the representation of ‘facts’. This approach is suggested by observations made by John Odell (1982) and Kathleen McNamara (1998) in separate studies of monetary policies. Both authors suggest that the representation of past policies may contribute to their adoption by groups.

John Odell’s study of American monetary policy (1982) identifies the content of ideas, such as the cognitive association with past policy failures, as having a determining part in the circulation of policy proposals (Odell; 1982; 68). Similarly, McNamara’s The Currency of Ideas presents the thesis that perceptions of past policy ‘failure’ and perceptions of the West German Bundesbank as an exemplar of ‘good policy’ were significant contributory factors to the conception of European Monetary Union (1998).

These points are particularly relevant to the Keynesian –Monetarist shift in 1970s Britain. The incumbent government was perceived to have made mistakes over inflation forecasts (1972), corporate tax increases (1974) and exchange rate intervention (1976) (Hall; 1993; 285). Perceptions of the government’s ‘failed’ performance undermined Keynesian demand management.

The issue here is perception, or more accurately, perception of (economic) phenomena. These phenomena are essentially mediated through politicians and the press (Barry; 1985; 294).

International relations authors have embraced the fact that foreign policy is often mediated to domestic audiences (Soroka; 2003). Consequently, the study of the forms through which events and societies are represented is considered to be important .This has produced a profusion of scholarship in diplomacy, feminism, and post-colonial studies (Sharp 2002; Jabri 1999; Achebe 1997). IPE has not yet studied this closely and so my paper may be considered a useful addition to the IPE literature.

3.3. Research questions

This paper will provide answers to the following two questions:

Question one; Are the current economic policy proposals presented by the British media based on Keynesian principles, or a New Interventionist adherence to efficient market theory?

Question two; How are price stability and fiscal balance being represented in the discourse?

-4 Methodology-

4.1. Media

My decision to study the media discourse follows Hall’s observation that the economic policy discussion in the newspapers was a significant factor in the Keynesian-Monetarist shift in 1970s Britain. (Hall; 1993;2 87). The literature identifies William Rees-Mogg, Daniel Feldstein and Samuel Brittan as influential monetarist advocates and economic advisers in the 1970s shift (Krugman, 1994; Hall, 1993; Blyth, 2002). The very same analysts are regular contributors to the current British Press and therefore it should be considered a good indicator of institutional change or resistance to change.

I selected five UK broadsheets and one news magazine, namely The Times, Telegraph, Independent, Guardian, Financial Times and The Economist. These publications were selected because they have comprehensive economic, finance and business sections. Furthermore, newspapers are specifically aimed at the British audience and are regarded as containing more commentary and advocacy than those in America (Schudson; 2005; 81).

4.2. Data Collection

It is typical for newsprint studies which use more than four daily publications, such as Villela- Villa & Costa-Font (2004), to observe a time period between six and twelve months. I chose a seven month period between 15th September 2008 and 30th April 2009. The time period is cross-sectional; the period was merely selected in order to generate a large volume of economic discourse, rather than to study the same items over an extended period of time. The choice of period was motivated by two reasons. Firstly, event driven stories provide a greater variety of voices (Schudson; 2005; 83). Secondly, it is thought that actor driven narratives are most conducive to reporting within a 24-hour news cycle (Galtung & Ruge; 1970). The period covered the insolvency of a major financial institution, Lehman Brothers, and finished after the UK budget. Therefore the period included significant events. Secondly, the news coverage was actor driven, because the time period encompassed two G20 Summits, the annual Davos Economic Forum, budget announcements in both Britain and America. This ensured that the population contained a large and sophisticated volume of economic discussion.

I followed the selection process employed by a past agenda setting study of economic policy (Jasperson, Shah, Watts, Faber & Fan; 1998). A population of articles discussing the Financial Crisis was compiled using the Lexis-Nexis database, Financial Times and Economist internet archives. These are reputable search engines used by academics and professionals.

I employed a detailed search string using ‘financial crisis’ followed by ‘fiscal stimulus’, ‘capital flow’, ‘balance of payments’ and ‘trade balance’. The search terms employed were neutral in disposition in order to avoid bias. For example, ‘hot money’ is a phrase used to describe capital flows, but is a phrase which implies a critical attitude as it was predominantly used to refer to the 1997 Asia Financial Crisis. I used terms that were devoid of adjectives and adverbs.

4.3. Sample

This produced a total population of 3254 articles, from which I pulled a sample of 830. I used a stratified sample in order to ensure an appropriate number of elements for representativeness. To each of the stratified samples I used systemic random sampling which involved calculating the individual skip interval.[6] Every fourth unit was sampled.

4.4 Content analysis

The unit of analysis was the discourse in UK broadsheet newspaper articles that were discussing ‘The Financial Crisis.’ Content analysis lends itself to the analysis of mass communication such as newspapers. For example, 34.8% of mass communication articles published during 1995 in Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly were content analyses (Riffe & Freitag; 1997). [7]

The recording units were individual sentences which contained economic policies as their subjects. This provided ‘ready made’ units. This decision was motivated by Neuendorf’s observation that it is often difficult to train coders to unitize individual topics (Neuendorf; 2002; 73). Sentences containing references to fiscal stimulus, monetary policy, capital controls and international trade imbalances were picked out. This ‘manifest’ content allowed a sentence to be coded as being part of the discourse. These were my independent variables. These sentences allowed me to code my dependent variable, economic theories. The policies are logically derived from foundational principles, and so should be considered to represent the ‘latent’ economic thought. This is due to the fact that they contain trigger words such as ‘self-correcting’ which allowed me to infer that the policy adhered to EMT, my dependent variable, an economic theory.

I used a descriptive content analysis and so applied an a priori coding scheme to my data. This enabled me to summarize messages and produce counts of key categories. This was a nominal coding scheme. Sentences were coded as presence of Keynesian proposal; a presence of a new interventionist proposal; sentences critical of Keynesian proposals; sentences which were discussing the policy area. By aggregating each of these categories, I was able to summarize the overall composition of the discourse.

4.5.1. Validity

To ensure high degrees of accuracy and precision, certain standards of validity needed to be achieved. The three policy areas investigated were demand management, capital controls and redesigning the international trade system. Keynesian and EMT prescribe very different policies in these areas and so they draw out the distinctions between schools of thought. In this way, the study had a satisfactory level of content validity.

Codes were being assigned to the policy recommendations of different schools of thought. Whilst reading Keynes directly is the best, it has been noted that the General Theory is a complicated text. In order to be confident in a high degree of face validity, I transposed policy proposals and economic explanations from Paul Davidson (Davidson 2007(a); 2007(b)). Davidson is a particularly clear interpreter and historian of Keynes. He has based a large proportion of his energies on policy proposals based on Keynesian economics, and so his public policy recommendations are logically deduced from Keynesian axioms Furthermore, coders were given examples of policies instruments which may have been manifestly similar to Keynesian policies, but contained trigger words that revealed latent efficient market theory. This allowed the study to claim a satisfactory level of validity. Large proportions of chapters 5, 6 and 7 are devoted to explaining the connection between economics and the policy. I have stayed close to Davidson, as validity was my major concern.

4.5.2. Reliability

The subjective nature of the enquiry suggested it would be highly advisable to have a second coder in order to ensure a high degree of consistency in judgement (Neuendorf ; 2002). My second coder was Sophie Riches, a fellow political science student at University College London. She should be considered a competent coder because she is also undertaking newsprint content analysis and has studied macroeconomic policy as part of a Master’s course. The enquiry benefited from the addition of ‘credibility’’ added by investigator triangulation (Neuendorf; 2000; 23). Wimmer and Dominick (1994) suggest that an adequate sub-sample for inter coder reliability would be between10-20% (See Neuendorf; 2002; 158). My subsample size was 10% of each code assigned. The selection again was systemic and random. I employed a simple agreement calculation, in which two coders code the same units. This was based on the observation that 65% of reported reliability adopted this approach (Hughes & Garret; 1990). I checked for agreement across individual codes to prevent one extreme success of failure distorting overall results (Neuendorf; 2002; 143). I chose Holsti’s method (1969). The consistencies were all within a threshold of 0.8 and 1 which is considered to be acceptable in most situations (Neuendorf; 2002; 143). [8]

4.5.3. A Constructivist’s Tool-kit

In order to describe the way in which price stability and fiscal balance were being constructed, I took an inductive approach. I undertook an open coding, employing salient techniques from critical theory, grounded theory method and discourse analysis. This eclectic approach allowed me to address the underlying concern of constructivism; the ways and techniques in which ‘the selection and structuring of language may produce facts’ (Flick; 2004; 289). Once the open coding had revealed constructions of interest and rhetorical devices, these were developed into a stipulated closed code so that they could be quantified. Again the closed codes were second coded for consistency. This ensured that the enquiry was driven by empirical evidence. The results and analysis of this study can be found in chapter 8. I will now provide details of my constructivist methodology.

Critical linguistics:

The object of study for critical theorists is how a particular interest is being presented as society’s interest (Geuss; 1981; 38).[9] Critical theory approaches to the newspapers were predominantly clustered in the1980s. The field experienced a lapse in interest due to the emergence of new media in the 1990s (Dahlgren & Gurevitch; 2005; 380). Significantly, the techniques employed by the approach have not been criticized on methodological grounds.

I took Fowler (1991) as a template due to its clear and methodical approach to the construction of political interests in newsprint. The author drew upon critical linguistics to analyze the British Media.

Fowler’s approach placed a particular emphasis on speech acts and modalities (Fowler; 1991; 86-87). Such constructions convey an attitude towards behaviour actions and states of affairs; namely what people should do and what people should want. The following four modalities are of particular interest to a critical theorist;

(i)Truth; this is a commitment to the truth of a proposition. It can vary in degree and says that proposition has happened or will happen. Adjectives such as ’unlikely’ or adverbs such ‘certainly’ are truth modals.

Example: Deflation increases the weight of the debt burden. (Economist– 5th March 2009).

(ii) Obligation; the writer stipulates that an action ought to be performed. Words of interest include ‘ought’, ‘should’ and’ must’ are the key items here.

Example; Why Obama has to find answer to the worst economic mess since FDR’s day. (The Guardian– 22nd November 2008).

(iii) Permission; The writer bestows permission to do something.

Example; Rich countries can afford to treat their currencies with benign neglect. Emerging economies cannot. (Economist -9th October 2008).

(iv) Desirability; the writer indicates a level of approval or disapproval about a state of affairs.

Example; Emerging economies have sought to earn their own spurs as inflation-fighters. (Economist- 11th December 2008).

Grounded theory method:

My inductive coding made use of the four most important aspects of grounded theory method (Bryman; 2004; 542); theory driven data collection, detailed open coding, constant comparison within categories and theoretical saturation. During the inductive open coding, the representation of the risk element associated with public policy emerged as an important concept. Subsequent data collection was ‘driven by an emerging theory’ (Glaser and Straus 1967; Charmaz; 2000; 519).This categorization was refined using constant comparison between texts (Bryman; 2004; 542). I continued this process until the categories were well established and ‘no new or relevant data’ seemed to be emerging (Bryman; 2004; 416). The progression to discourse analysis was a natural progression once a theme, portrayal of risk, became apparent.

Discourse analysis:

My approach looked at the way in which ‘the categories relating to and depicting an object form the way that the object is comprehended’ (Bryman; 2004;499). My treatment of the discourse surrounding budget deficits and inflation paid close attention to the ‘rhetorical organization’ of the text (Gill; 2000; 176). My approach satisfied the criteria of established discourse theorists such as Potter by studying the purpose, structure and resources employed in a text (Potter; 2004; 609). I provided ‘precise details to support theoretical assertions’ and included ‘summative statements to bring details into line’ within a British socio-historical framework (Neuendorf; 2002; 6).

-5 Fiscal and Monetary Policies-

5.1. Keynesian theory behind demand management

Prior to Keynes, economists categorized aggregate demand for all the products of industry within one group. The model predicts that that supply and demand support each other, because aggregate income is spent on all of the products of industry. This provides the aggregate incomes that will fund further demand (Davidson; 2007(a); 59-61). On this view, investment is relatively constant because supply will generate demand and demand will return profits.

Keynes’ notion of uncertainty about the future led him to reconceptualise this category. In particular, Keynes did not include investment spending in the traditional aggregate demand, because he doubted that it would be equivalent to planned savings at all possible levels of income. For Keynes, the more uncertain the future seems, the smaller the amount income spent on domestically produced goods. This lack of demand for goods will lead to less investment and consequently less employment in industry. In such circumstances, domestic standards of living will fall.

In this way, Keynes provided a logical argument for government intervention in the private economy; in order to sustain GDP in the face of falling consumption and investment, government expenditure needs to rise as a direct substitute for private consumption and investment. Governments can affect employment by increasing expenditure on goods and services. This action will increase sales and therefore sustain employment directly (Keynes; 1936; 377-380).

5.2. Coding Demand Management

Independent variable; demand management policies

These policies were introduced as either fiscal ‘stimulus’ or ‘expansion’. Items included injections of capital into a stagnant economy through either government spending or reductions in value added tax.

To be considered Keynesian, a policy instrument had to satisfy the condition that it included public programmes which served as a substitute for business activity because business expands only after profit (Keynes, 1933; 354). In addition to this, the instrument needed to recommend internationally coordinated stimuli (Keynes; 1933; 356).

Keynesian policy was one aiming to manage; liquidity preference, uncertainty causing underinvestment or the need for inflationary expectations to induce current spending. I drew a distinction between policies designed to ‘fix’ employment and policies designed to manage employment and making explicit reference to Keynes. The latter were categorized as having a Keynesian justification.

In terms of policy instruments, increased government spending or VAT reductions alone were to be coded ‘New Interventionist’. Important trigger words to capture New Interventionism were words such as ‘fix’, ‘mend’ or ‘medicine’ to describe the intervention. Such words imply fixing a temporary problem.

The coding benefited from an initial pilot coding of 10% of the articles. Firstly, it revealed that ‘calibrated’ stimulus was a prominent proposal. This is a proviso that the stimulus should borrow from a budget surplus. In such a way, it does not prescribe discretionary fiscal policy for a social project and therefore is not Keynesian. Calibrated stimulus was to be coded as New Interventionist.

This pilot coding also revealed that fiscal and monetary stimuli were often mentioned in the same sentence. These are distinct policies. Whereas fiscal stimulus alters the distribution of money in an economy, monetary stimulus increases the availability of credit or quantity of money in an economy. It became necessary to develop another code.

5.3. Coding monetary policy

Independent variable; credit easing policies

In this latter category were policies introduced as ‘monetary stimulus/expansion’, ‘quantitative easing’ and ‘credit easing’. Monetary stimulus aims at increasing availability credit of credit in the economy, through interest rate cuts or through a central bank creating additional money.

It should be noted that Keynes did think that ordinarily central banks should keep interest rates low and make credit readily available (Keynes; 1923; 353). However, I did not include this in my definition of Keynesian management because (a) Keynes was writing in the days before central bank independence and I was not aware of Keynes‘s view of independence and (b) Keynes advocated these credit conditions as a permanent policy.

Monetary stimuli were open coded. The items of interest as far as the Keynesian-New Interventionist debate was concerned were policies designed to ‘fix’ a temporary contraction of credit lines.

5.4. Challenging EMT: Keynesianism challenges efficient market theory because Keynesianism denies that the current problems are temporary, and recommends permanent regulation of aggregate demand. This thought generates two hypotheses.

5.5. Hypotheses

H1- A greater proportion of the economic discourse between 15th September 2008 and 30th April 2009 will feature New Interventionist proposals for demand stimulus than Keynesian demand management proposals.

H2- A greater proportion of the economic discourse between 15th September 2008 and 30th April 2009 will propose credit easing and quantitative in order to restore credit lines.

5.6. Results

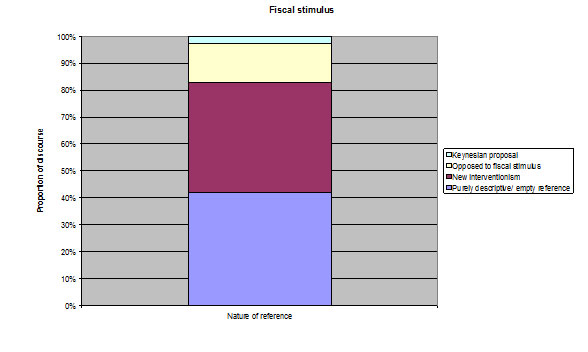

The results shown in figure 1 demonstrate that Keynesian proposals for a fiscal stimulus were significantly outnumbered by New Interventionist policies. Therefore H1 was correct.

Figure 1: Composition of fiscal stimulus discourse

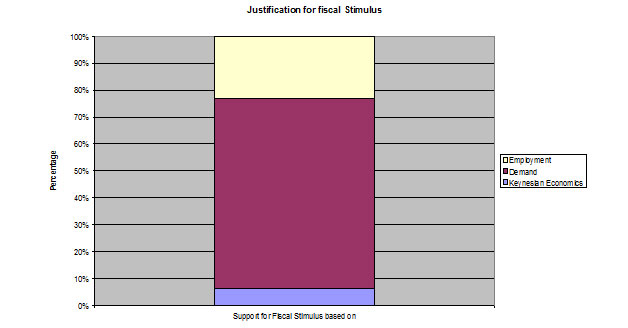

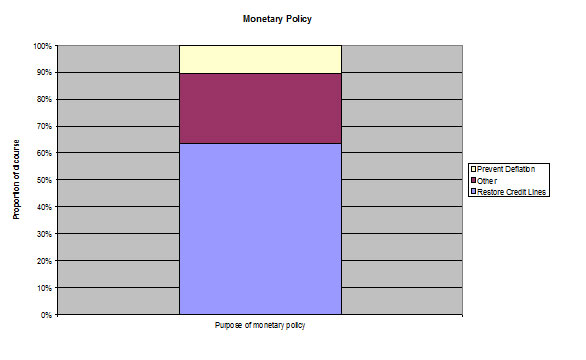

The greatest proportion of stimulus proposals sought to stimulate demand. Furthermore, it can be seen from figure 3 that t he predominant objective of monetary policy was to restore credit lines. These findings mean that H2 was correct. Fixing demand and credit were the objectives of the ‘new’ policies.

Figure 2; purpose of fiscal stimulus

Figure 3; purpose of monetary stimulus

-6 Capital Controls-

6.1. Keynesian theory behind capital controls

Keynes’ thinking on investment was informed by both his philosophical studies at Cambridge and his personal experiences of speculating on the stock market (Lawlor; 2006; 132-133). Keynes described the human behaviour through which disruptive ‘all or nothing’ behaviour occurs and anticipated the detrimental effect that speculation could have on real investment. When confronting their own uncertainty about the future, investors either made conjectures based on available price signals, or copied the actions others facing the same situation (Keynes; 1937; 213-214).

This short-sighted mentality can lead to the exuberant peaks or pessimistic troughs which disrupt orderly markets. Rising capital market prices can encourage over exuberance and over-investment (Davidson; 2007(b); 16). If doubts arise, an excessive demand for liquidity will impede the production of new investment capital (Lawlor; 2006; 261). Within Keynes’s conceptual framework, uncertainty begets a demand for market liquidity.

Since investment was integral to Keynes’s treatment of output and employment, any inhibition of investment had to be considered a direct threat to employment (Lawlor; 2006; 150). Consequently, Keynes recommended the management of investment through restrictions on the movement of financial capital.

6.2. Coding capital controls

Independent variable; policy instruments

At a symposium in 2000, Davidson suggested a list of Keynesian capital control policies. This list included: differentiated exchange rates for different types of transaction; taxes on specific financial transactions; raising interest rates to slow capital outflows; raising bank reserve ratios; limiting the purchase of foreign securities by banks and regulation of interbank activities (Davidson; 2007(b);21).

In order to be considered a Keynesian proposal, the policy had to mention the effect of speculation on investment. Coders were instructed to code plain advocacy of capital controls and a negative attitude towards protectionism.

6.3. How does this challenge EMT?

Capital controls challenge the assumption that present information can guide individuals to make optimizing decisions. Furthermore it is a protectionist policy. This means that it challenges the neo-liberal move towards liberalized markets, in which price and wage flexibility allocate resources efficiently. This generated the following hypothesis and sub-hypothesis.

6.4. Hypotheses-

H3– A greater proportion of the economic discourse between 15th September 2008 and 30th April 2009 will feature policy proposals critical of capital controls than the proportion of proposals for Keynesian capital controls.

Sub- Hypothesis 3- A greater proportion of the economic discourse between 15th September 2008 and 30th April 2009 will feature support for liberalization than proposals for Keynesian capital controls and other proposals for capital controls.

6.5 Results

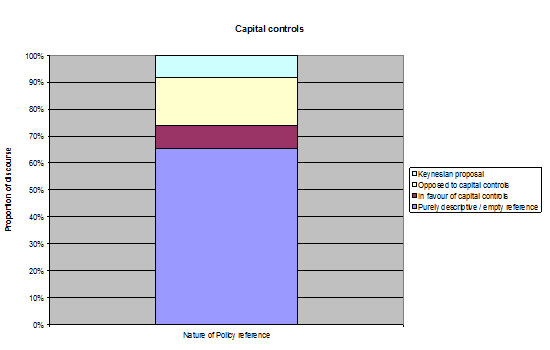

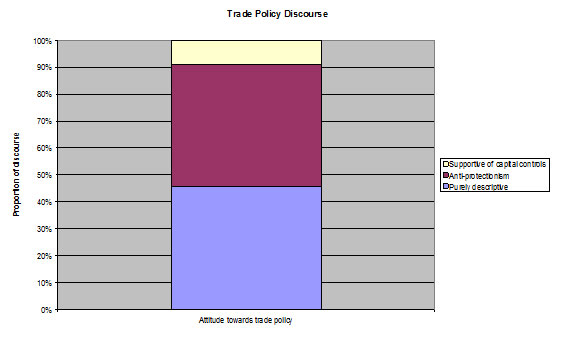

H3 was correct because a greater proportion of policies criticized capital controls than supported Keynesian proposal or policies in favour of them. It should be noted that this was only by a small margin. Furthermore, the only proposals of protectionist policies were specifically financial controls. This suggests that the EMT faith in liberalized markets is considered disputable. It is possible that the discourse reflected a distinction made by Bhagwati, between volatile financial markets and less volatile goods and services (Bhagwati;1998;1,4). This suggests an avenue for further study, one which elaborates on the bundling together of types of liberalization and the effect that discussing the issues of financial protectionism and trade for goods and service has on reader’s attitude towards the issue.

Figure 4: Composition of capital control discourse

A much greater proportion of trade policy discourse was anti-protectionist than the proportion supportive of capital controls. This supported the sub-hypothesis.

Figure 5: Composition of Trade Policy Discourse

-7 Trade Imbalances-

7.1Theory behind Keynesian international trade reform

The third policy item is reform of the international trade system. Inspired by The General Theory and Keynes’ Work in the UK Treasury during the Second World War, Davidson has worked extensively on issues of financial governance. The groundwork and policies are explained at length in Chapters 8 and 10 of Davidson’s 2007a.[10]

Keynes’ position at the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference was that there was an incompatibility between advanced financial liberalization and full-employment and rapid growth. In a world with liberalized capital markets, the most feasible way for a government to promote its domestic economy would lead to a surplus of liquid assets in its current account. The consequence of this would be to induce deflationary pressures in those countries which are running current account deficits.

Much of Davidson’s theory derives from chapter Twenty Three from The General Theory (Davidson; 2007a; 119). In theory, an increase in domestic investment should follow a reduction in domestic interest rates. However, in practice it is unlikely that a competitive advantage would be established. In the current era of liberalized capital markets, one would expect governments to court foreign investment by engaging in a competitive interest rate ‘race to the bottom.’

Keynes pointed out that in such a situation governments have no direct controls over the rate of employment (Keynes; 1936; 336). Keynes identified that only the current account could provide a means to attract foreign capital and thereby increase domestic employment and income. Keynes effectively provided an analysis of the pressures that lead a government to pursue an export led growth policy (Davidson; 2007(a); 120).More abstractly, Keynes described a motivation for holding liquid assets.

If a country exports more than it imports, it will accrue a current account surplus. Keynes recognized that a trade imbalance will result in unemployment in the import competing industry overseas (Davidson; 2007(a); 121).The orthodox policy responses to this problem include devaluing exchange rate or reduction of nominal wages. The likely outcome of such policies is the reduction of domestic living standards (O’Brien; 2007; 68).

The Keynesian thought is that a liquidity preference can stifle effective global demand. When working on designs for a post-war international economy, Keynes suggested the establishment of an International Central Bank, institution through which current account imbalances could be centrally managed. Keynes provided an innovative proposal that that the nation enjoying the current account surplus resolves the imbalance (Keynes; 1933; 355-356). This would involve relinquishing liquid assets, namely foreign exchange reserves (Skidelsky; 2003; 627-8). Furthermore, overdraft facilities were to be made available to provide liquidity for those with a low reserve currency. This would reduce possible motivations for hoarding liquid assets.

7.2 Coding trade reform

Independent variable; policy instruments

To be considered Keynesian, polices had to place the onus on creditor nations to resolve current account imbalances. Coders were looking for policies whereby creditor nations agree to spend excessive holdings of foreign exchange reserves on one of three options;(a) foreign direct investment in debtor nations,(b) buying the imports of countries against which they have accrued that surplus or (c) foreign aid to deficit nations.

Policy instruments which called for IMF reform, but no reference to a revised role for creditor nations, were coded as ‘New Interventionist’. Similarly, policies which suggested that creditor nations should increase their contribution to the IMF emergency fund were to be coded as ‘New Interventionist’ because such proposals reinforce efficient market theory. These solutions assume that the problem of nations having a preference for liquid assets is fixable.

7.3. Challenging EMT:

Keynesian reform of the world trade system challenges the existing floating exchange rate system. On EMT, a balance of trade imbalance ought to be resolved by the debtor nation. The debtor will devalue its domestic currency, leading to an increased consumption of the now cheaper goods. The result will be to balance the current account.

7.4.Hypothesis

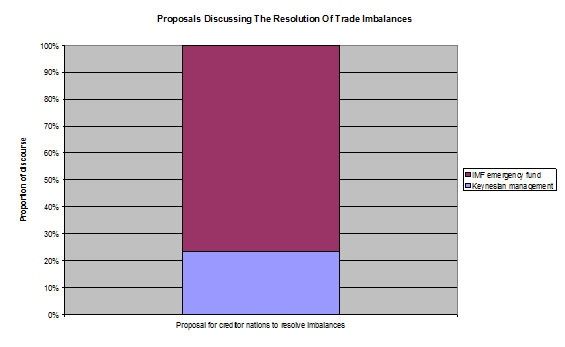

H4- A greater proportion of the economic discourse between 15th September 2008 and 30th April 2009 will feature New Interventionist proposals for IMF reform than the proportion of proposals for Keynesian management of trade imbalances.

7.5. Results

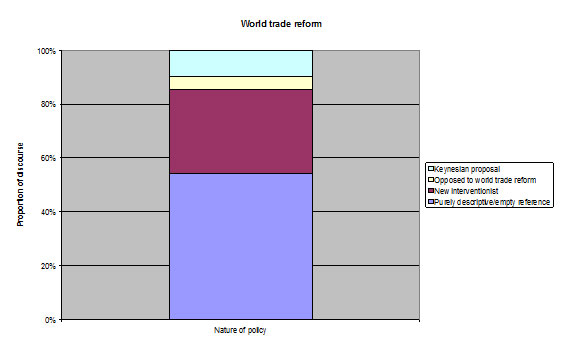

The results in figure 6 show that there was a consensus that creditor nations had a wider role to play in the settling of trade imbalances.

Figure 6; Composition of trade reform discourse

A second observation from the results was that world trade reform was the policy area in which Keynesian proposals constituted a greater proportion of the discourse can other Keynesian policies. This is illustrated in figure 7.

Figure 7; Nature of support for capital controls

However, it can be seen that H4 is correct, because advocacy of a new role for creditor nations was dominated by suggestions that creditor nations provide more for IMF emergency funds. This can be considered an endorsement of EMT.

Figure 8; Composition of proposals for creditor responsibility for imbalances

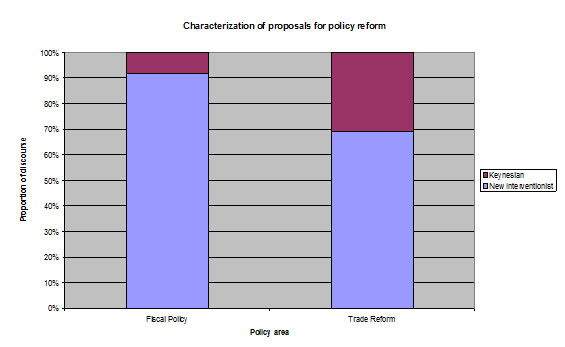

-8 The (Old) Politics of New-Interventionism-

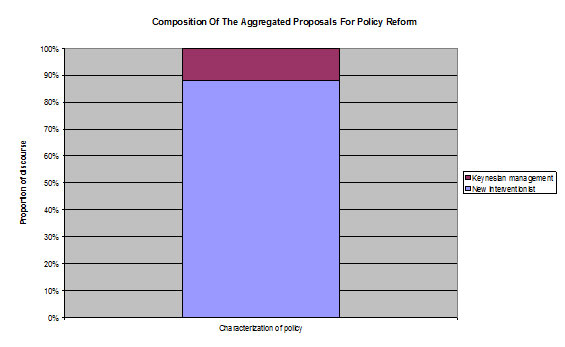

The results in chapters 5, 6 and 7 demonstrate that a greater proportion of discussions of policy reform could be characterized as ‘New Interventionist’ than Keynesian management. Across the all three policy areas, nearly 90% of proposals for reform were characterized as New Interventionist. This can be considered to be an endorsement of EMT.

Figure 9: Composition of the aggregated proposals

With this conclusion in place, the focus now is to study the representation of price stability and fiscal balance.

8.1. The representation of inflation.

The ‘critical’ aspect of the enquiry revealed that inflation was represented as a phenomenon that could and should be kept low. Firstly, inflation was described as a force such as a ‘tsunami’, namely something that could be ‘unleashed’, ‘stoked’, or ‘reignited. ’ Past central bankers such as Eddie George (UK) and Paul Volker (US) were exalted for their achievements in ‘crushing’, ‘taming’ or ’breaking the back of inflation.’(Economist -20th November 2008).

Secondly, inflation targeting emerged as an opiate against the uncertain and unpredictable economic climate. Readers were told to ‘hold on to the fact that inflation will be kept low’ (Telegraph– 2nd April 2009).

Thirdly, Inflation targeting itself was portrayed as the ‘economic philosopher’s stone’’ (Financial Times- 22nd February 2009). In other instances, inflation targeting took the form of a term of appraisal. It was desirable for a government to implement inflation targeting. Britain’s ‘sixteen years without inflationary strains’ made it a ‘paragon’ (Economist 12th February 2009). Furthermore, countries which had used interest rate increases and taxation to control inflation were considered to have ‘earned their spurs’ as ‘inflation fighters’. (Economist- 11th December 2008).

8.2. Representing price stability and fiscal balance

8.2.1. Theory emerging with data.

The grounded theory method revealed that in that a recurrent theme was being used to represent the nature of the risk associated consequences of fiscal and monetary policy. This was an example of theory emerging alongside data. The media represented the consequences of fiscal stimuli and quantitative easing as threats to society. Price stability and fiscal retrenchment were represented as the solutions to these problems.

8.2.2. Representing risk

The grounded theory method revealed that the consequences of the new fiscal and monetary policies were being presented in a manner which accentuated the sense of risk to society.

It became clear that the data should be coded, paying close attention to the way in which inflation and public sector budget deficit were being represented. A closed coding scheme was generated and then applied. My methodology was influenced by Jacqueline Best (2008) and John Odell (1982).

My discussion of governance of risk is informed by the work of Jacqueline Best. Taking Foucault’s discussion of epidemiology as her starting point, Best explains that economic policy, such as securitization, attempts to govern through the logic of calculation and risk management (Best; 2008; 368-369). This is a consequence of the Arrow-Debreu method of statistical modelling used by efficient market theorists to forecast future market conditions (Beckert; 1996). Risk is defined as ‘the statistically accurate probability distributions of future information, based on data currently available’. All future events are defined as more or less probable variations on present and past events. In this way, risk is being represented in calculable terms (Best; 2008).

Using this theoretical approach, I constructed a closed coding scheme which distinguished between representations of calculable and incalculable risk. Calculable risks were items framed in mathematical, scientific or positivist terms, such as projected figures and estimates, or numerical language such as ‘quantitative easing’. Incalculable risk was defined as items which express a lack of control over a policy outcome such as ‘wheelbarrows of money’ or ‘nuclear option.’ Other items considered to be representations of incalculable risk were those which quantified the risk in the manner such as a ‘black hole.’

My inductive coding revealed that phrases associating economic policies with the management of calculable risk, were coupled with or even outnumbered by metaphors, analogies, adjectives or adverbs that served to heighten the risk by representing the risk in incalculable terms. The representation of incalculable risk was accompanied by calls for ‘mid-term fiscal restraint’, ‘credible commitment’ to an ‘exit strategy’ and ‘sterilization’ of excess money. In this way the media’s representation of policy reinforced the norms of price stability and fiscal balance.

Here, a reading of John Odell’s study of American monetary policy, (1982) is extremely useful. Odell noticed that after a decision had been made, bureaucrats and government officials often tried to rationalize decisions that were improvised or ad hoc at the time they were made. Odell described the process through which the representation of calculation was considered to a sufficient, if not necessary, condition of establishing a ‘good’ policy (Odell; 1982). In the discourse under observation, ‘rational’, calculable policy approaches such as exit strategy, sterilization and fiscal balance were advocated in order to protect society from incalculable risks of inflation and budget deficits. In this way, price stability and fiscal balance constitute good governance.

8.2.3. Outline of the argument

This paper proposes that the following framework is in place;

1. The public policy is represented as a calculable risk.

2. The discourse represents the policy in terms of an incalculable risk. The text was organized in manner which fixed the interpretation to the risk element of the policy.

3. Construction of society’s interest. The public debt and future inflation was represented as unmanageable risk unless medium term retrenchment occurred. In each case, representation reinforced the organizing principles of ‘sound finance.’

-9 Representing the Consequences of New Interventionism-

9.1. Fiscal Policy

9.1.1. Presenting calculable risk.

A fiscal stimulus requires public borrowing. The government presents this borrowing in calculable terms. This is manifest in the term ‘budget’ alone. Pre-budget reports and forecasts occur every autumn whilst the budget and future forecasts are presented every spring.

9.1.2. Representing unmanageable risk

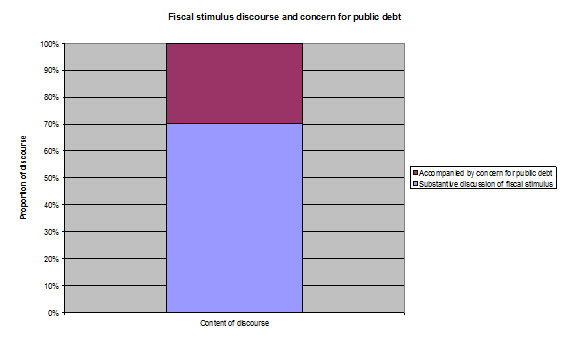

The increased public spending required to finance demand management was associated with a concern for public debt and budget deficit in the newspaper press. Nearly a third of the substantive discussions of fiscal stimuli were accompanied with this interpretation. This is illustrated in figure10.

Figure 10: Concern for public debt

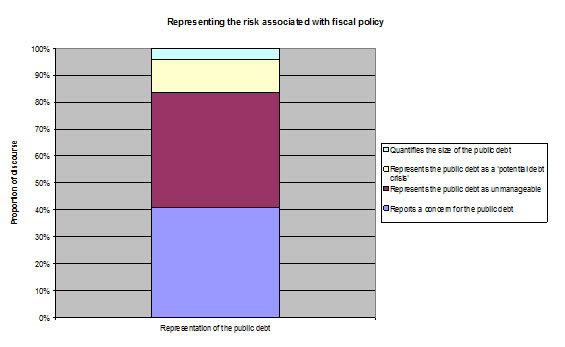

In April The Times pointedly remarked upon Chancellor Alistair Darling’s failure to include ‘indebted’ from his description of the British economy in his budget speech. The public finances were described as ‘rotten’ and a ‘black hole’ (Guardian, 26th April 2009). The media were also conveying the sense that the ‘mountain of’ public debt was ‘sky-high’, ‘ballooning’, and ‘spiralling out of control’. Britain’s government had a ‘shattered reputation’ for economic management. One can see that the risk element was the most prevalent form of representation of public debt, when one compares the proportions of the discourse in figure 11:

Figure 11; Fiscal policy and risk

9.1.3. Constructing society’s interest

A large public debt was being represented as a risk to society. Discussions of the public debt made use of analogy to the ‘humiliation’ of IMF intervention in 1976. Two powerful techniques that connect social stigma to indebtedness were employed to reinforce the principle of fiscal balance.

Firstly , the creditor-debtor relation of social inequality was reinforced through imagery of ‘begging bowls’, ‘pleading’ and ‘going cap in hand’, to either the IMF or emerging economies such as China or India (Times -26th April 2006). Britain was described as having gone from a ‘paragon to a pariah’) due to a ‘borrowing binge.’ (Economist– 12th February 2009).

The second technique involved social exclusion, which hinged on an axis of prudence and profligacy. Readers were introduced to ‘badly behaved’ countries, such as ‘Argentina’, which have ‘unbalanced budgets and no current account surpluses’. ‘Well behaved countries’, such as Brazil, were praised for their fiscal ‘responsibility’ (Economist –13th October 2008).

The modality expressed in this discourse was that it was desirable for the government to return to the principle of fiscal balance; Treasury bond investors must be convinced that the government is committed to long term fiscal discipline. (Economist- 2nd April 2009). Similarly ‘an independent body for debt targeting’ was advocated (Telegraph 19th March 2009).

9.2. Monetary policy

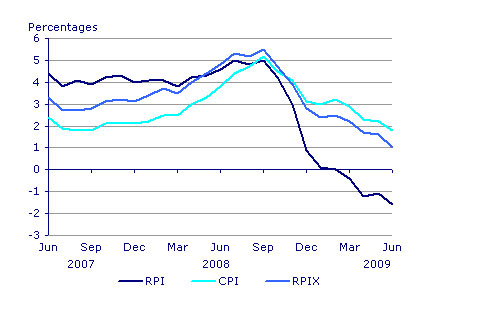

This discursive framework can also be applied to the monetary policy discourse. In February, Britain experienced deflationary pressures and the Retail Price Index measure (RPIX) of inflation became negative. The effect of deflation, falling prices and wages, is to increase the real rate of interest. This consequently increases the likelihood of defaults on debt.

Figure 12; Inflation statistics for the UK

CPI inflation 1.8%, RPI inflation -1.6%

Source; National Office of Statistics.

The conventional response to deflationary pressures is for a central bank to reduce interest rates. By reducing the cost of borrowing, demand for money should increase. The Bank of England had been reducing interest rates from October 2008, but with interest rates as low as 0.25% in April 2009, this orthodox policy was no longer viable. The Bank of England embarked on a course of unconventional monetary policy, namely quantitative easing.

9.2.1. Quantitative Easing

On the 5th of March 2009 the UK Debt Management Office created an Asset Purchase Facility (APF). This heralded the expansion of the Bank of England’s balance sheet by £75bn. The Bank would purchase government bonds (gilts), corporate bonds and paper money from banks, pension funds and other institutions at inflated prices. It was hoped that these funds would be reinvested in riskier assets. The aim of this policy is to lower the cost of borrowing for companies and households.

9.2.2. Representing calculable risk

Quantitative easing should be considered an exemplar of defining a policy in calculable terms. The very title, ‘quantitative easing’ employs calculable terms, and each injection is announced following meetings by the Monetary Policy Committee of senior economists at the Bank of England.

9.2.3. Representing unmanageable risk

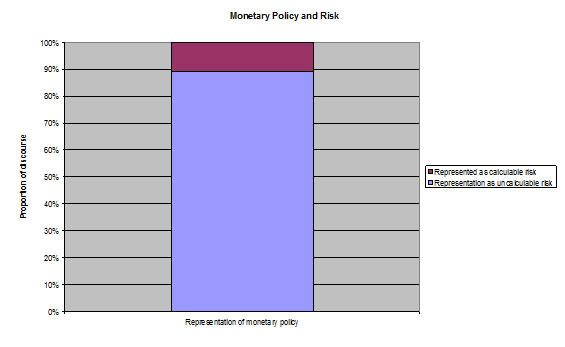

Over 90% of the references to quantitative easing were accompanied by allusions to less manageable risk such as ‘alchemy’, ‘sorcery’, and ‘a last throw of the dice.’ There was a litany of references to ‘monetary ammunition’ and ‘powerful weapons’, the majority of which emphasized the high level of risk created by the operation. Clear examples of this were ‘nuclear response’, ‘nitro-glycerine’ and ‘shock and awe tactics.’ In figure 13, one can see extent to which the incalculable risk element was prevalent in the discourse;

Figure 13; the representation of monetary policy and risk.

The risk being represented reinforced the principles of price stability and inflation targeting. As shown in figure 12, Britain experienced deflation in February. Yet, by March, inflation was cast as the ‘new fear.’ Quantitative easing is inflationary, because it increases the quantity of money circulating in an economy. However, as in the 1970s, the consequences of inflation were being represented as those associated with hyperinflation (Blyth; 2002; 147). The uncertainty surrounding quantitative easing saw the imposition of a rhetorical device to explain the two outcomes facing the economy. A dichotomy of deflation or hyperinflation appeared in 25% of the discussions advocating QE in March and April. This is shown in figure 14.

Within this dichotomy, the predominant analogy employed to describe the nature of the deflation was the ‘Japanese lost decade.’ One can contrast the vagueness of this reference to a reference which fixes a calculable assessment. For example, one could fix the meaning by presenting Reinhardt and Rogoff’s study that after a crisis a drop in growth of 2-5% of GDP for three years (Reinhart & Rogoff;2008(a);1).

The second half the dichotomy exhibited a much clearer fixing of the meaning. References fixed the meaning to hyperinflation, economic mismanagement and failed states. This was accomplished by the prevalence of analogies to ‘wheelbarrows of notes ’, ‘Weimar Germany’ and ‘Zimbabwe.’ (Guardian & Economist February 2009)

Figure 14: prevalence of deflation- hyperinflation dichotomy in discussions of quantitative easing.

9.2.4 Constructing Society’s interest

Hyperinflation is often the result of a government being unable to finance its expenditure and public debt through fiscal policy. However, no calculable analysis indicates that Britain is on a hyperinflationary course. Even during the days of large deficits and inflationary crises, none of the members of the OECD allowed large deficits to accelerate into hyperinflation (Barry; 1985; 283). Even so, calculable analyses of the likelihood of this type were seldom employed in the discourse.

The situation was being represented as one of ‘double jeopardy’; quantitative easing would have to be taken to avoid deflation, but would lead to hyperinflation unless reassurances of a ‘medium- term exit strategy’ were included. This would essentially involve aggressive increases in interest rates and taxation. In this way, the discourse reinforced the organizing principle, that good governance requires a commitment to inflation targeting and price stability. An interesting example from the discourse was provided by economist Federic Mishkin, who advocated a ‘positive numerical inflation objective’’ (Financial Times– 11th January).

-10 Conclusion-

This paper sought to investigate the extent to which political and economic discourse reinterpret the organizing principles and the regulatory rules of a system. In order to do so, it characterized the policies which genuinely pose a challenge to the assumptions of Efficient Market Theory. The paper raised four hypotheses and one sub-hypothesis.

The first two hypotheses proposed that the majority of solutions to the financial crisis would seek to fix or reboot the credit fuelled consumerism of the Great Moderation. These hypotheses proved to be correct. The issues with the economy were perceived to be fixable contractions of credit and demand, rather than its systemic instability.

The third hypothesis stated that a greater proportion of the discourse would be critical of capital controls than the proportion proposing the management of capital flows. The sub-hypothesis was that anti-protectionist policies would be more prevalent than the proportion of policies advocating any form of controlling the free movement of capital. Both the hypothesis and the sub-hypothesis were borne out by the results.

The final hypothesis was that proposals for reform of the world trade system would reinforce the current system, rather than reconstruct it. A higher proportion of proposals, which improved credit facilities for debtor nations, were proposed than Keynesian proposals for imbalances to be managed by creditor nations. Again this hypothesis was correct.

This study found that a greater proportion of the economic discourse in British broadsheet newspapers proposed policies that were ‘New Interventionist ‘ rather than Keynesian. These findings lead me to draw the conclusion that the policy discourse in broadsheets did not challenge the assumptions of EMT. Therefore this paper supports David Hudson’s characterization of the current policies as ‘New Interventionism.’ There has been no significant change in economic thought.

This paper also found that the policy discourse reinforced the principles of price stability and fiscal balance. By representing the risk associated with fiscal and monetary policy as being incalculable, the discourse proposed that the government commit itself to mid-term fiscal and monetary retrenchment. The representation of risk determined which policies were deemed to be legitimate. Only by adopting the ‘credible’ and calculable rules of price stability and fiscal targets could the policies be considered to be ‘good governance.’ In such a way, the discourse reinforced the principles of price stability and fiscal balance.

The major thought raised by this conclusion is that ‘good governance’, through price stability and fiscal balance, oversaw a financial crisis. The policy discourse proposed that these principles of ‘good governance’ ought to be reinstated once the economy is functioning again. In conceiving of the crisis as a temporary contraction in demand and credit, economic thinkers are not challenging the contradiction between purportedly good economic governance and economic crises.

-Appendix 1-

Skip interval calculation for random sampling

population÷ sample = every nth unit to be sampled.

3254 ÷ 830 = 4 so every 4th unit was selected an assigned an identifier.

Inter coder reliability tests

Inter coder reliability- Holsti’s method

Pao= 2x A /(na +nb).

A = the number of agreements.

n=number of units coded by coders A or B.

Fiscal stimulus

Empty reference; (2x 28) ÷ 60 = 0.93

Keynesian; (2×2) ÷ 4 =1

Against Keynesian proposal; (2×10) ÷ 20= 1

New interventionist; (2x 23) ÷ 54 =0.85

Monetary policy

Empty reference; (2x 19) ÷ 40= 0.9

Against monetary policy; (2x 3) ÷6 = 1

In favour; 2 x 13 ÷ 32 = 0.813

Demand; 2×4 ÷ 8=1

Credit 2x 11 ÷ 11=1

Capital controls

Empty reference; 2×13÷ 28 = 0.928

Keynesian proposal; (2×1) ÷2= 1

In favour of capital controls; (2×1) ÷2= 1

Against capital controls; (2×3) ÷ 8=0.8

Trade imbalances

Empty reference; (2x 4) ÷ 10=0.8

Keynesian proposal; (2×1)÷2 =1

In favour creditor nation taking responsibility; (2x 1) ÷2= 1

Against reform ;2×2÷ 6 = 0.8

Budget deficit and risk

Budget deficit as calculable risk (2 x1 ) ÷ 2 = 1

Budget deficit as incalculable risk (2×9) ÷ 18 = 1

Potential crisis (2×2) ÷ 6 = 0.8

Matter for concern (2 x 7) ÷ 18 = 0.78

Quantitative easing and risk

Quantitative easing as calculable risk (2x 20) ÷ 42= 0.95

Quantitative easing as incalculable risk (2×19)÷ 38= 1

-Appendix 2-

Selected results of content analysis:

Monetary policy

| Code |

Number |

|

Empty reference to credit easing |

200 |

|

Supportive of credit easing |

163 |

|

Opposed to credit easing |

30 |

|

|

|

Fiscal policy

|

CODE |

NUMBER |

|

Empty reference to fiscal stimulus |

298 |

|

Keynesian stimulus |

18 |

|

New Interventionist stimulus |

292 |

|

Opposed to fiscal stimulus |

104 |

Capital controls

| Code | Number |

| Empty reference to capital controls | 136 |

| Keynesian Management | 17 |

| In favour of capital controls | 18 |

| Opposed to capital control | 37 |

Trade balances

| Code | Number |

| Empty reference to trade balance | 45 |

| Keynesian management | 8 |

| New Interventionist proposal | 26 |

| Opposed to reform of the world trade system | 4 |

Objective of monetary policy

| Purpose of Policy | number |

| Stave off deflation | 17 |

| Restore credit lines | 104 |

| Misc.others | 43 |

Objective of fiscal stimulus

| Purpose of policy | Number |

| Maintain employment | 67 |

| Fix demand problem | 204 |

| Keynesian management | 18 |

Representation of quantitative easing

| Representation | Number |

| As calculable risk | 214 |

| As Incalculable risk | 190 |

Prevalence of hyperinflation dichotomy in discussion of quantitative easing

| Time Period | proviso | unequivocal Support |

| Jan/feb | 7 | 56 |

| March/ April | 15 | 31 |

Representation of budget deficit

| REPRESENTATION | NUMBER |

| Calculable risk | 9 |

| Potential crisis | 25 |

| Incalculable risk | 90 |

| A matter for concern | 85 |

Bibliography

- Abdelal,R, Blyth, M & Parsons, C. (eds). (2010). Constructing the International Economy. (Ithaca; Cornell University Press).

- Achebe, C. (1997). ‘An Image of Africa; Racism in Conrad’s Heart of darkness.’ Pp.209-221. In Castle, Gregory Ed. 1997. Post Colonial Discourses; an anthology. (Oxford; Blackwell).

- Alesina, A & Summers, L. (1993). ‘Central Bank Independence and Macroeconomic Performance. Some Empirical Evidence.’ Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. Vol.25 no.2 (May 1993).

- Aradau, C & Van Munster, R (2007). ‘Governing Terrorism Through Risk: Taking Precautions, (un)Knowing the Future’ European Journal of International Relations, (2007); 13; pp89- 116.

- Barnett, M, & Finnemore, M. (1999) ‘The Politics, Power and Pathologies of International Organizations.’ International Organization 53 (4) Autumn 1999; pp699-732.

- Barry, B (1985). ‘Does Democracy Cause Inflation? Political Ideas of Some Economists’; In Lindberg, L. & Maier, C.(1985); pp280-318.