In the night of July 10th 2010, armed militants burned down the media centre of PACT Radio in Jalalabad, eastern Afghanistan (PACT Radio, 11 July 2010). In the same year, at least three foreign journalists in the country were taken hostage (Committee to Protect Journalists, 15 February 2011). The fact that the press has become a target in the Afghan conflict, stresses the importance of the media as an instrument of warfare and power. Indeed, the ability of the media to spur ethnic hatred and promote violence has been notoriously witnessed in the last decade of the 20th century in the conflicts in the Republic of Yugoslavia, Rwanda and the Soviet Republic of Georgia (Frohardt and Temin, 2007: 389).

Yet the media is a ‘double-edged sword’ (Howard et al., 2003). Its other edge – the ability to reconcile communities after civil conflict and contribute to peacebuilding – has, however, been less widely recognised. Few organisations working in conflict zones have adopted media interventions as part of their peacebuilding efforts.

The mass media entail much more than news and current affairs. The possibilities with radio, TV, print, mobile phones and the internet are almost endless, ranging from phone-in talk-shows, to comic books, and from soap opera to songs and blogs. All of these formats could be used towards peacebuilding, which has the overarching goal to develop local capacity to resolve conflict without violence, in order to improve human security (Paris, 2004).

This essay will attempt to highlight some of the untapped opportunities that lie in effectively using the media as an instrument for peacebuilding. It will first discuss the reasons why media interventions have thus far not been integral parts of peacebuilding missions, drawing a distinction between news media and “intended outcome” media. The subsequent discussion of peacebuilding will show that the latter are particularly well-suited to serve peacebuilding ends.

The second part of the essay exemplifies these claims by looking at the case of Afghanistan. The Afghan conflict and media-scape will be briefly sketched, followed by a detailed description of the BBC media intervention New Home, New Life. The difficulties of measuring the success of media interventions will be discussed before turning to the reasons for the success of the BBC project. The focus throughout the essay will be on the medium of radio, yet a brief discussion of new media will also be included. Finally, the question how the media have been used as a successful means for peacebuilding in Afghanistan will be answered.

Media and Peacebuilding

Peacebuilding involves a multitude of activities, all aimed at decreasing the probability of violent conflict. The different activities intend to change the security, political, economic and social environment of a country (Weiss-Fagen, 1995). On the individual level, this implies cognitive, attitudinal and, eventually, behavioural changes that reflect a shift from polarisation to positive relationships and from violence to peace (European Centre for Conflict Prevention, 2007). Media can play a role in all of these categories. In fact, the United Nations classified the development of local media as a ‘cross-cutting’ peacebuilding concern, ‘transcending’ all types of activities (United Nations, 1996: 3).

In this light, Robert Karl Manoff argues that independent media have an almost inherent capability to contribute to conflict resolution and peacebuilding. He points out that the basic functions of media are the same as those involved in conflict-resolution processes: channelling communication to counter misperceptions; framing and analysing conflict; identifying interests; defusing mistrust and providing emotional outlets (Manoff, 1998).

Nonetheless, the use of media as a peacebuilding tool is still controversial. The vast majority of the peacebuilding literature blatantly omits the role of the media (Call and Wyeth, 2008; Roeder and Rothchild, 2005; Paris, 2004; Otunnu and Doyle, 1998; Miall et al., 2005) and this trend is also visible in policymaking: the Dayton Accords, which ended the Bosnian war, did not include any media intervention plan, and the Millennium Development Goals make no mention of the importance of independent local media.

There are two reasons for this ‘apparent blindness’ (Howard et al., 2003) to use media in peacebuilding. The first is that politicians, the military and aid organisations often perceive the media as a threat (Adam and Holguin, 2003: 1). There is a fear that any incautious remark, military strategy, or confidential document will be published by the media, without consideration of the consequences to the conflict.

The second reason is that journalists themselves are uncomfortable with their role as peacebuilders. This function is perceived to be incompatible with the basic journalistic principle of objectivity, which dictates that the media should merely report, and not play any part in a conflict. Diverting from the objectivity principle may cause the media to lose their credibility, and thus their “market value” (Bourdieu, 1996).

A strong stance can, however, be made against these objections, as the media have inevitably been involved in recent conflicts.[1] A new school of journalism thus argues that the media have a moral responsibility to report in a manner that does not champion warfare, but promotes peace (Lynch and McGoldrick, 2007). This “peace journalism” is, however, not the only way in which the media can contribute to peacebuilding. The media can also be used in a more pro-active manner to promote the aforementioned cognitive, attitudinal and behavioural changes in society. These programmes are distinct from news reporting or peace journalism and dubbed “intended outcome” journalism.[2] Whilst not dismissing the importance of peace journalism, this essay will focus on the intended outcome media interventions, as their success in peacebuilding has been more robustly demonstrated. The case-study of Afghanistan will demonstrate how an intended outcome program can contribute successfully to peacebuilding.

The Afghan conflict

The Islamic Republic of Afghanistan is highly socially fragmented. The major ethnic groups are the Pashtun (42%), the Tajik (27%), the Hazara (9%), and the Uzbek (9%), with other minor ethnic groups comprising another 13 percent of the population (Central Intelligence Agency, 2011). These divisions are also reflected in the country’s languages: the official Dari and Pashto are spoken by 50 and 35 percent of the population respectively, whilst some thirty other languages are also in usage (Central Intelligence Agency, 2011). Many people are bilingual, and the mixing of languages is common, with few people speaking a pure form of one of the languages (Skuse, 2002b: 423).

In the mountainous country with a predominantly rural population (77% (Central Intelligence Agency, 2011)), the state has historically had weak authority outside the capital Kabul (BBC News, 2011). The past thirty years of its history have thus been characterised by instability and conflict.

The incessant violence can be described as three subsequent civil war phases (Giustozzi, 2000; Giustozzi, 2007; Maley, 2002). The first phase started in 1978, with the coup of the left-wing People’s Democratic Party. Intra-party power struggles and rural armed revolt of the conservative Islamic mujahideen, provoked the Soviet invasion in 1980. This occupation was continually challenged and finally defeated in 1989. The second phase arose after the Soviet retreat, when the victorious mujahideen started fighting each other for power. From this struggle emerged the Taliban, who advanced rapidly from 1994, and seized Kabul within two years, introducing radical shari’ah law. The third phase of the war is marked by the 2001 invasion of Western coalition forces to overthrow the Taliban regime. The current government under president Karzai faces resurgent Taliban attacks. In 2010, civilian deaths reached an all-time high since the 2001 invasion (Afghanistan Rights Monitor, February 2011).

The Afghan media-scape

The ongoing conflict has inevitably affected the Afghan media environment. Under communist rule, there was a widespread distribution of cheap transistor radios, as well as wide availability of Chinese-made batteries. Radio thus was and still is the most accessible medium for the majority of the population (Rene et al., 2010).[3] The national radio station Radio Afghanistan was, however, dominated by radical communist broadcasting (Bradsher, 1999). Advisers of the Soviet Intelligence Agency (KGB) created suitable propaganda programmes and a censorship system. Typically, captured mujahideen fighters were forced to confess their “sins” on air (Skuse, 2002a: 270).

As a result of this propagandist broadcasting, Radio Afghanistan became highly unpopular. A former employee of the station recalls: ‘there was so much propaganda on the radio it became boring for listeners and most people developed an aversion to Radio Afghanistan’ (quoted in Skuse, 2002a: 270).

Following the Soviet retreat, Radio Afghanistan was destroyed by the mujahideen. Under the subsequent Taliban regime, the station was re-established as Voice of Shari’at Radio. Although denouncing communism, the propagandist nature of the broadcasts did not change substantially. Most airtime was allocated towards explanation of Islamic morals and Shari’ah law (Skuse, 2002a: 273). The Taliban furthermore banned television, film, printed imagery, music and the broadcasting of female voices (Skuse, 2002a: 273).

Against this background, it was unsurprising that the Afghan people started looking for alternative sources of information and entertainment, in the form of international radio broadcasts. The Afghan state did not have the technical capability to exclude these foreign signals. Many partial broadcast services, such as Voice of America, Radio Pakistan, Radio Iran and All India Radio, became popular, yet the vast majority of Afghan listeners tuned into the BBC World Service.[4] The BBC Persian and Pastho Services were seen as the most impartial and credible sources of information and thus became ‘socially constructed as the de facto national broadcaster of Afghanistan’ (Skuse, 2002a: 274).

New Home, New Life

Having secured this large, loyal audience, the BBC World Service used this foundation to extend its programming to intended outcome programmes. The rationale was to help the Afghan people with socially useful information to survive in the war-torn country. The format chosen in 1994 was based on the production model of BBC Radio 4 The Archers: a radio soap opera.

For the past seventeen years, the soap opera New Home, New Life[5] has been broadcasted three times a week at prime time for fifteen minutes. It addresses a wide range of social, economic, political and humanitarian problems, including conflict resolution, health, hygiene, the oppression of women and the dangers of unexploded landmines. The “edu-tainment” format, which embeds the information in dramatic storylines, prevents being explicitly didactic (Skuse, 2011: 2). It relies on the audience to draw its own conclusions from the dilemmas with which they are presented. By creating a ‘fictional “space”’ to discuss and question taboo topics, the soap opera attempts to take a first step towards attitudinal and behavioural change (Adam, 2005).

The research that preceded the production of New Home, New Life was extensive. Afghan writers, broadcasters and actors were recruited among refugee populations in Pakistan.[6] A high level of cooperation with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) ensured that storylines were technically correct and culturally appropriate.

The soap opera is broadcasted in both Dari and Pashto, in simple, colloquial language. Indeed, as one listener remarked: ‘I like soap opera more than other programmes because I am an illiterate man and […] cannot follow the BBC’s other programmes [due to the complexity of its language]’ (Skuse, 2002b: 423). The actors and actresses, being from different parts of the country, disguise their accents in order to fit into the fictional community.[7]

To appeal to the largest possible segment of the Afghan population, it was decided to stage New Home, New Life in a rural context. However, as Afghanistan is a vast and geographically diverse territory, it was difficult to choose a realistic setting that would allow “soap time” to run parallel with “real time”. The alignment of the two is crucial to encourage certain behaviour at an appropriate moment, for instance in harvesting season or during festivals (Skuse, 2002b: 418).

New Home, New Life was instantly popular among both men and women[8] and has remained so up to this day. Numerous times, the soap opera caused popular outcry: when one of the main characters, Faiz Mohammed, died by a stray bullet in a fight between two families, a plethora of letters reached the BBC office and one town even held a funeral service for the character (Adam, 2001). Even the Taliban were loyal listeners, despite the pro-women agenda of the drama.[9]

Evaluating success: a challenge

The aim of New Home, New Life was to change attitudes and behaviours to contribute to peacebuilding. Success is thus achieved when key themes are ‘understood, remembered, discussed and acted on’ (Adam, 2005). There are, however, multiple problems with the evaluation of this success.

The first is that surveying the audience is complicated by a lack of infrastructure. Moreover, it is difficult to measure intangible aims such as attitudinal changes (Curtis, 2000: 153-54). The fact that the goals of intended outcome programmes are long-term, poses another problem to evaluation attempts. Additionally, in a conflict-affected region, numerous aid and peacebuilding organisations are active. This complicates attributing measured changes to one particular project. Finally, even when behavioural change is measured, it remains problematic to distinguish reported from actual change; what people say they do may differ from what they actually do (Adam, 2005).

Many media peacebuilding projects are not sufficiently analysed due to a combination of these predicaments. This is problematic, for an unclear understanding of the impact of these projects impedes the ubiquitous acceptance and implementation of media interventions in peacebuilding.[10]

New Home, New Life, however, has tackled these evaluation challenges: their substantial funding by Red Cross, UNDP and UNICEF facilitated long-term evaluation in remote areas; the fact so few other media projects were present in Afghanistan made it possible to attribute impact to the BBC; and some storylines aimed for more tangible results that allowed the separation of actual and reported change.

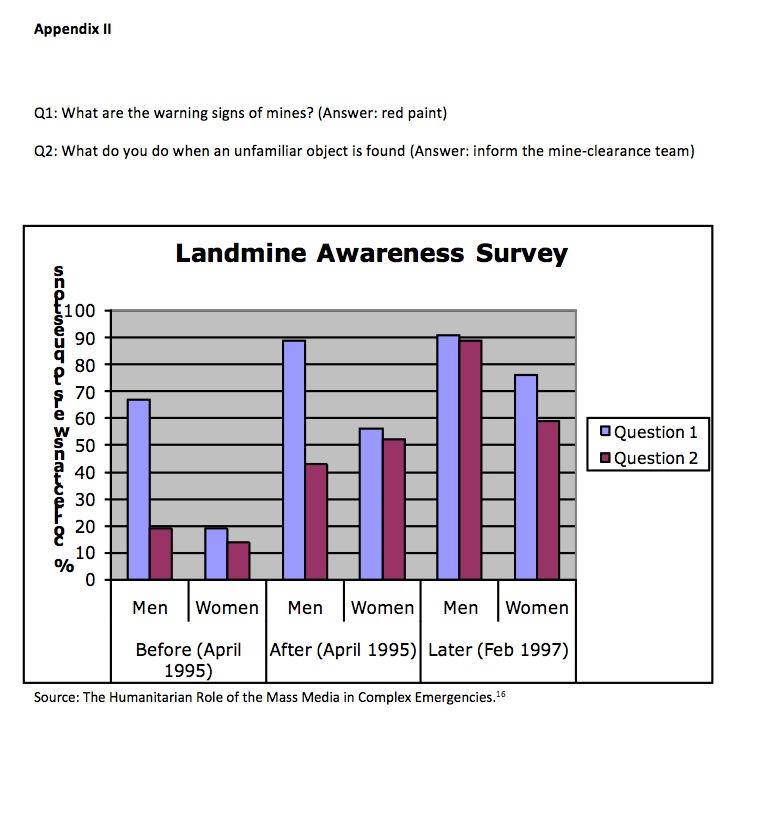

One such storyline was concerned with the awareness of unexploded landmines. The BBC Afghan Education Projects (AEP) systematic ally evaluated whether the lessons about landmines, embedded in the storyline, were understood and remembered by the audience. The results showed a large increase in attained knowledge among listeners (Adam, 2005).[11] Proof that listeners also acted on their knowledge emerged from the 1997 CIET International Mine Awareness Evaluation. This evaluation indicated that the BBC had a significantly positive impact on the casualties caused by landmines: a non-listener was twice as likely to be a mine victim than a listener. This contrasted starkly with the lack of impact of the other mine awareness programmes evaluated in the report, all of which were face-to-face (Andersson et al., 1998).

Anecdotal evidence also indicates the success of the BBC in generating behavioural change. In 1998, a journalist recorded that a woman told that the example of Gulalai, a female health worker in New Home New Life, had convinced her to allow her daughters to work outside the house’ (quoted in Adam, 2005).

Reasons for success

The effectiveness of New Home, New Life in achieving peacebuilding objectives can be attributed to multiple factors. The first factor is its format. The pro-active intended outcome design of the soap opera is suitable to convey messages without being perceived as propaganda. Its entertainment value also fills a gap in the market, as the Afghan population is ‘isolated and starved of entertainment’ (Adam, 2005). The format also provides listeners the opportunity to question norms and established practices within the “safe space” of fictional events (Skuse, 2011). Finally, the running storylines allow the repetitive highlighting of important issues without boring the audience. This reiteration is crucial to achieve normative change (Adam, 2005).

The second factor that accounts for the success of New Home, New Life is its local specificity and cultural appropriateness, ensured by the extensive research in the pre-production phase. Mary Anderson points out that it is important for peacebuilders to identify the connectors of a society, such as common systems, attitudes, experiences, values and symbols (Anderson, 1999). By emphasising these connectors, New Home, New Life promotes the reconciliation of groups. Moreover, by researching the local norms, the soap opera avoids being seen as too modernising. Through subtle character transformations, that are still within the realms of the “conservative”, the drama opens up space for debate (Skuse, 2011: 13). In this way, New Home, New Life does ‘the do-able’ and tackles obtainable objectives (Adam and Holguin, 2003: 9). A final and important aspect is the concern that a rural, isolated and under-educated audience may find it challenging to engage in comprehensive societal discussion (Olorunnisola, 1997: 247). By broadcasting in the two main languages in colloquialisms, setting the drama in a rural context, and making the storylines relevant to people’s everyday lives, New Home, New Life entices rural audiences to consider broader topics of peacebuilding.

Partnerships of trust are the third bedrock of the success of the soap opera, most notably between the BBC and local Afghan broadcasters, writers and actors. The education of the local team was all-important in the long-term viability of the project.[12] Additionally, partnerships with NGOs are cherished for providing crucial information to develop storylines, and reinforcing the BBC messages on the ground. An example of cooperation are the National Immunisation Days, when New Home, New Life advocates the importance of the vaccination campaigns. NGOs also distribute a New Home, New Life cartoon magazine (Adam, 2005).

For a message to achieve its desired effect, the source must be deemed credible by the audience. The fourth basis of success is thus the trust in and credibility of the BBC as a media outlet. As elaborated above, the BBC had firmly established this trust in Afghanistan before New Home, New Life was aired.

Finally, listeners’ views of the radio drama are taken into account. Through audience surveys and focus groups, feedback is presented to the scriptwriters and producers.

All these factors contribute to the feeling of “ownership” of New Home, New Life among the Afghan population (Adam, 1999: 5). In this way, the soap opera has firmly established itself over the past seventeen years as an instrument for peacebuilding within a challenging war-torn environment.

One recurrent critique of the production is its overtly positive portrayal of new economic possibilities, which omit the realities of extreme poverty. In order to inspire the audience to embark on new income-generating activities, these must appear to pay off, even though, in reality, many obstacles may cause their failure. Indeed, an educational soap opera is always ‘a few degrees rosier than real life’ (Skuse, 2002b: 417).

Looking ahead: New Media

No discussion of the use of media in peacebuilding is complete without mention of the opportunities that the advance of new media, particularly mobile phone technology and the internet, offer. When the Taliban government was overthrown in 2001, the telephone network in Afghanistan was virtually non-existent. At the moment, there are twelve million mobile phones (Central Intelligence Agency, 2011), with around 300,000 being sold monthly (Adam, 2008). Some 85 percent of the country is covered by mobile network (Adam, 2008). The user fees are dropping rapidly and evidence from neighbouring Pakistan shows that text messages are being sent by all classes of society, indicating that low education levels do not form a barrier to texting (Adam, April 2009). Internet use is also proliferating, with some 1 million internet users nationally (Central Intelligence Agency, 2011) and around 900 internet cafes in Kabul (Adam, 2008).

While the exact significance of the new media “revolution” for peacebuilding is still hard to pin down, the use of social networking sites Facebook and Twitter to organise protests in Colombia, Iran and Egypt, and the use of text messages for activist mapping by the Ushahidi website during the post-election violence in Kenya, are promising examples of the possibilities. In Afghanistan, a new project called Mahaal allows people to receive the news on their mobile phone. As mobile phone coverage is now more ubiquitous than radio coverage, this is a particularly useful way to disperse information in remote areas (Adam, 16-03-2011).

The greatest potential of new media is their ability to make media peacebuilding interventions more participatory. Dialogue is the first step in creating the sense that disputes should be settled through negotiation rather than violence. Radio phone-in shows are ideally suited to spur this dialogue within the safety of anonymity (Adam and Schoemaker, 2010: 39).[13] The Taliban realise this potential of phone-in talk shows to challenge their radical views (Sameem, 24 March 2011); in 2010, mobile phone companies reported a sharp incline in the number of transmitter towers destroyed by insurgents (Adam and Schoemaker, 2010: 39).

Conclusion

As Adam and Schoemaker point out, ‘access to information is a vital building block for lasting peace’ (2010: 35). Despite this fact, there has been a large-scale omission of media as an instrument for peacebuilding (Himelfarb, 2009). This essay has demonstrated that there is a great untapped potential for intended outcome media to serve as peacebuilding tools.

The format of the radio soap opera, as exemplified by New Home, New Life, has proven particularly effective as such. Although each conflict is unique, it has been replicated in Cambodia, Rwanda, Kenya, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Colombia, Albania, Rumania, Russia, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, indicating the universality of the reasons for its success (Adam and Holguin, 2003: 15). From this follows that the role of media in peacebuilding should move beyond the strengthening of independent news media, to explore all the possibilities of intended outcome media, including new media technology.

Media may not be able to solve conflicts, but there is certainly an important role for them in spurring debate, reconciling communities and changing behaviour towards peacebuilding. It should be remembered, however, that media interventions are not a “quick fix” (Adam and Schoemaker, 2010: 39). It is important to allow the long-term processes that can facilitate attitudinal and behavioural change to blossom.

New Home, New Life has been the focus of this essay, yet many more interesting media interventions have been staged globally. These include a commercial phone-in program in Nigeria (Adam, 2011), a “peace journalism” radio station in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda (Betz, 2004; Dahinden, 2007), a training centre for journalists in Indonesia (Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information, 2004) and a peace song produced by famous Angolan musicians (Adam and Holguin, 2003). It was beyond the scope of this essay to discuss this broad range of media possibilities.

Bibliography

Adam, G. 16-03-2011. Interview. Methodist Central Hall, London.

Adam, G. 1999. The Media and Complex Humanitarian Emergencies. Humanitarian Exchange Magazine, 13 (March).

Adam, G. 2001. The Humanitarian Role of the Mass Media in Complex Emergencies. Presentation at TUFTS University Boston.

Adam, G. 2005. Radio in Afghanistan: a model for socially useful communications in disaster situations? World Disaster Report Geneva: Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

Adam, G. 2008. Winning Hearts and Minds in Helmand. The Sunday Herald.

Adam, G. 2011. An Analysis of Media-driven change in Nigeria. Briefing Paper for DFID.

Adam, G. April 2009. Communication, development and… counter terrorism. Glocal Times.

Adam, G. & Holguin, L. 2003. The media’s role in peace-building: asset or liability? OUR Media III Conference. Barranquilla.

Adam, G. & Schoemaker, E. 2010. Crisis State Communication. Stabilisation Through Media. RUSI Journal, 155 (4), 34-39.

Afghanistan Rights Monitor February 2011. Annual Report Civilian Casualties of War January-December 2010. Kabul.

Anderson, M. B. 1999. Do No Harm. How aid can support peace – or war. London, Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Andersson, N., Whitaker, C. & Swaminathan, A. 1998. Afghanistan. The 1997 National Mine Awareness Evaluation. CIET International.

BBC News. 2011. Afghanistan country profile. Available: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/country_profiles/1162668.stm#media [Accessed 29-03-2011].

Betz, M. 2004. Radio as Peacebuilder: A Case Study of Radio Okapi in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Great Lakes Research Journal, 1 (December), 38-50.

Bourdieu, P. 1996. On Television and Journalism. London, Pluto

Bradsher, H. S. 1999. Afghan communism and Soviet intervention. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Call, C. T. & Wyeth, V. (eds.) 2008. Building States to Build Peace, London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Central Intelligence Agency. 2011. The World Fact Book, Afghanistan. Available: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/af.html [Accessed 30-03-2011].

Committee to Protect Journalists. 15 February 2011. Attacks on the Press 2010: Afghanistan. Available: http://www.cpj.org/2011/02/attacks-on-the-press-2010-afghanistan.php [Accessed 27-03-2011].

Cottle, S. 2006. Mediatized Conflict. Maidenhead, Open University Press.

Curtis, D. E. A. 2000. Broadcasting Peace: An Analysis of Local Media Post-Conflict Peacebuilding Projects in Rwanda and Bosnia. Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 21 (1), 141-166.

Dahinden, P. 2007. Information in Crisis Areas as a Tool for Peace: the Hirondelle Experience. In: Thompson, A. (ed.) The Media and the Rwanda Genocide. London: Pluto Press.

European Centre for Conflict Prevention 2007. Why and When to Use the Media for Conflict Prevention and Peacebuilding. Issue Paper 6.

Frohardt, M. & Temin, J. 2007. The Use and Abuse of Media in Vulnerable Societies. In: Thompson, A. (ed.) The Media and the Rwanda Genocide. London: Pluto Press.

Giustozzi, A. 2000. War, Politics and Society in Afghanistan, 1978-1992. London, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers.

Giustozzi, A. 2007. Koran, Kalashnikov, and Laptop: the Neo-Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan. New York, Columbia University Press.

Himelfarb, S. 2009. Media and Peacebuilding: The New Army Stability Doctrine and Media Development. United States Institute of Peace.

Howard, R., Rolt, F., Veen, H. v. d. & Verhoeven, J. 2003. The Power of the Media: A Handbook for Peacebuilders. Utrecht, European Centre for Conflict Prevention.

Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information 2004. The Role of Media in Peace-Building and Reconciliation. Central Sulawesi, Maluku and North Maluku. Jakarta.

Lynch, J. & McGoldrick, A. 2007. Peace Journalism. In: Webel, C. & Galtung, J. (eds.) Handbook of Peace and Conflict Studies. London: Routledge.

Maley, W. 2002. The Afghanistan wars. New York, Pelgrave.

Manoff, R. 1998. Role Plays: Potential media roles in conflict prevention and management. Track Two, 7 (4).

Miall, H., Ramsbotham, O. & Woodhouse, T. 2005. Contemporary Conflict Resolution. Cambridge, Polity Press.

Olorunnisola, A. A. 1997. Radio and African rural communities: Structural strategies for social mobilization. Journal of Radio & Audio Media, 4 (1), 242-257.

Otunnu, O. A. & Doyle, M. W. (eds.) 1998. Peacemaking and Peacekeeping for the New Century, Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

PACT Radio. 11 July 2010. Militants destroy PACT media centre. Available: http://www.pactradio.com/index.php?p=story&stid=254 [Accessed 28-03-2011].

Paris, R. 2004. At War’s End. Building Peace After Civil Conflict. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Rene, R., Tariq, M. O., Ayoubi, N. & Haqbeen, F. R. 2010. Afghanistan in 2010. A Survey of the Afghan People. Kabul: The Asia Foundation.

Roeder, P. G. & Rothchild, D. (eds.) 2005. Sustainable Peace. Power and Democracy after Civil Wars, London: Cornell University Press.

Sameem, I. 24 March 2011. Taliban stop cell phone signals in key Afghan province. Reuters [Online]. Available: http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/03/24/us-afghanistan-taliban-phones-idUSTRE72N1VI20110324 [Accessed 31-03-2011].

Skuse, A. 2002a. Radio, Politics and Trust in Afghanistan. A Social History of Broadcasting. International Journal for Communication Studies, 64 (3), 267-279.

Skuse, A. 2002b. Vagueness, familiarity and social realism: making meaning of radio soap opera in south-east Afghanistan. Media, Culture & Society, 24 (3), 409-427.

Skuse, A. 2011. Radio soap opera, gossip and social change in Afghanistan. Department of Anthropology, Adelaide University.

United Nations. 1996. An Inventory of Post-Conflict Peace-Building Activities. New York, Department for Economic and Social Information and Policy.

Weiss-Fagen, P. 1995. After the Conflict: A Review of Selected Sources on Rebuilding War-torn Societies. War-Torn Societies Project – Occasional Paper No. 1. Geneva: UNRISD.

[1] All contemporary warring parties are aware of the power of the media and manipulate or even stage events to further their strategic interests through media coverage. This phenomenon is called “spin” (Cottle, 2006).

[2] Howard et al. (2003) identify a scale of five types of media peacebuilding interventions, ranging from creating an independent local news media, to pro-active media interventions.

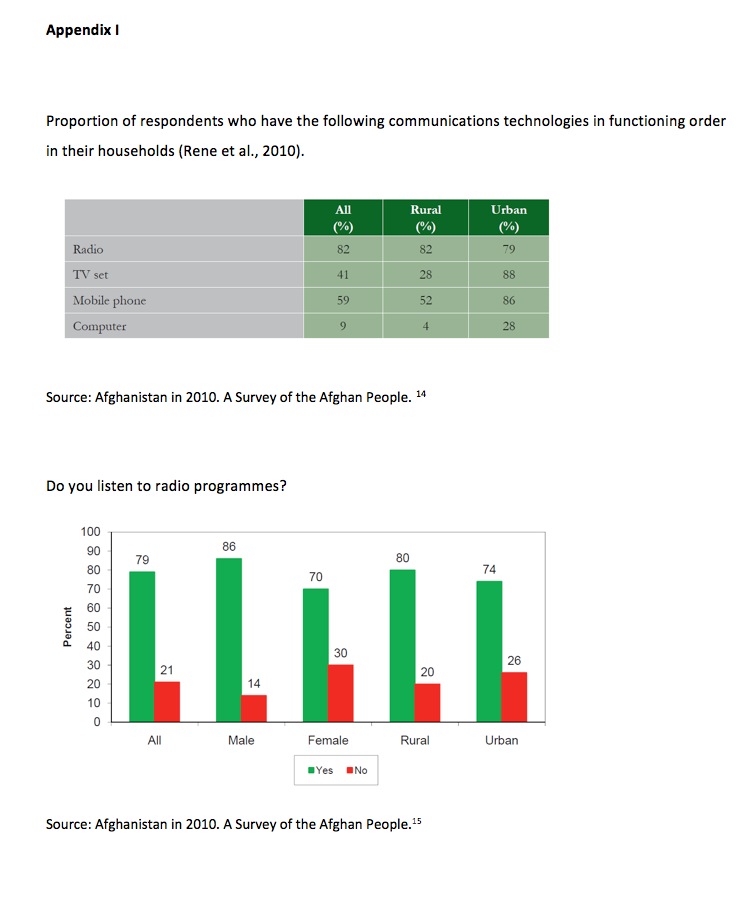

[3] This is particularly true in rural areas, where radio ownership and listenership peaks. See Appendix I.

[4] In 1998, 79% of Afghans listened to the BBC (Skuse, 2002a: 275), plus some five to six million Afghan refugees in Pakistan, Iran and the Gulf States (Adam, 2005).

[5] Khana-e-nau, Zindagi-e-nau (Dari) and Naway Kor, Naway J’wand (Pashtu)

[6] The BBC broadcasted from Peshawar in Pakistan, as Afghan cities were either not safe or too remote (Adam, 2005).

[7] The BBC Somali service set up a soap opera modelled after New Home, New Life, which failed to gain the trust of the audience, as the accents of the actors were associated with one particular clan. (Adam and Holguin, 2003: 11-12).

[8] In Afghanistan, following the news is typically seen as men’s business. Soap opera thus provides a unique opportunity to reach the female population (Skuse, 2011).

[9] On a number of occasions, the Taliban even issued decrees that were sparked by the soap opera. For instance, one storyline followed Asghar, a madrassah (religious school) student who was suddenly sent to the front. In response, the Taliban prohibited young students to be sent to battle and arranged madrassahs to school them (Adam, 2005).

[10] Many NGOs evaluate their media projects in an ad-hoc manner that is not convincing to policymakers. In Bosnia, for example, one NGO media project wrote in its “lessons learned” report: ‘Although no one can quote statistics or empirical evidence to indicate that new violence was averted or new democracy was nurtured, there was a palpable sense among all those concerned that both of these things had, in fact, been achieved’ (quoted in Curtis, 2000: 153). The NGO Search for Common Ground is one of the few to set up systematic evaluations of media peacebuilding projects.

[11] See Appendix II for a visual representation of the findings.

[12] A failure to provide this kind of educational partnership was demonstrated in Bosnia, where the international community provided funding to local media outlets, but no training or support in developing appropriate programming. The result was boring and badly produced local radio, with audiences tuning back to state broadcasters, who were still partisan and at times propagated ethnic hatred (Curtis, 2000).

[13] Successes have been reported in Sierra Leone, where rape and women’s rights were put on the agenda by local radio talk shows (Adam, 2008), and in Mali, where a text-in radio programme settled a dispute between farmers and cattle-holders (Adam and Holguin, 2003: 1-2). Online, bloggers could be encouraged to debate in a similar format.

[14] (Rene et al., 2010: 147)

[15] (Rene et al., 2010: 149)

[16] (Adam, 2001)

Written by: Maite Vermeulen

Written at: King’s College London

Written for: Preeti Patel

Date written: March 2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Iraqi Disarmament Crisis: What Lessons Can Be Learned?

- How Should the International Criminal Court Be Assessed?

- Can the Use of Torture in Intelligence Gathering Be Justified?

- To What Extent Can Natural Disasters Be Considered State Crimes?

- To What Extent Can History Be Used to Predict the Future in Colombia?

- Can Islamist Movements Be Moderated Through Political Participation?