Introduction

In recent years, there has been growing literature promoting the tenets of market forces in helping to alleviate the poverty of many people throughout the world. Authors such as William Easterly, Robert Calderisi and Dambisa Moyo argue that foreign aid does not work as well as the market when it comes to combating poverty. Additionally, the value of the private sector in development was acknowledged at the recently-held Fourth High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness in Busan, South Korea. This paper will examine the extent to which these market-based approaches can serve to help the poor in developing countries, specifically in Africa.

It is, of course, difficult to quantify exactly how to measure “helping the poor.” Some academics will simply rely on the growth of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as an indicator of improved development. While GDP has an important place in the topic at hand, it is important to recognize its limitations. For instance, Equatorial Guinea has the 22nd highest GDP per capita in the world, according to the World Bank’s 2010 data. Despite its high GDP, most citizens in Equatorial Guinea live in poverty, with the vast majority of the country’s wealth controlled by a tiny minority of individuals. The percentage of people that live below the poverty line can be more indicative of poverty alleviation, but it too has its limitations. This paper will therefore use a nuanced approach in analyzing how certain market forces help the poor. Economic growth, equality, freedom and human rights are all part of a holistic development analysis.

The paper will analyze market-based approaches to development in two main sections. First, China’s approach will be critiqued, which tends to be one of massive Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). In general, pro-market advocates are quite supportive of China’s African approach, though this paper will explain limitations of the pure FDI strategy. Next, other market strategies will also be explored, noting the limit that these have in aiding the world’s poor. These strategies include trade and microfinance.

Authors advocating the use of the market in development tend to be quite critical of foreign aid. Some authors, such as Dambisa Moyo, go as far as saying, “The problem is that aid is not benign – it’s malignant. No longer part of the potential solution, it’s part of the problem – in fact aid is the problem.”[1] Due to the limitations of this paper, no space will be devoted to explaining the real reasons behind Africa’s poverty. It will be assumed that the explanation of Africa’s desperate situation is much more complicated than simply foreign aid, and includes the continent’s geography, colonial history, structural adjustment programs and arbitrary borders, to name only a few factors. The paper also recognizes that there is an ongoing debate about the validity of foreign aid; however, it will be assumed that foreign aid does have a necessary role in the nuanced approach to development. Therefore, the focus of the paper will not be on foreign aid’s role in development, but the limits of the capitalist market in development. The paper will show that while the free-market is a necessary and important aspect of development, it has distinct limitations and must not be relied upon as the sole approach to poverty alleviation.

The Chinese Approach

In its frantic quest to fuel its rapid development, China has recently invested heavily in Africa. There is little disagreement on the reasons behind the investments; China desperately needs natural resources – specifically oil – in order to maintain its high rate of growth. Whether or not this policy is helping Africans is the topic of much disagreement.

In terms of human rights in Africa, China is deserving of harsh criticism. Unlike some Western aid, China’s investment in Africa is not conditional upon good governance and the promotion of human rights. China will invest anywhere that is of economic benefit. For instance, China has invested heavily in oil-rich Sudan, thus enriching and empowering the Sudanese government. Under pressure from non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the Canadian oil company Talisman even stopped doing business in Sudan because of human rights abuses by the Sudanese government.[2] The same cannot be said of China:

China has only increased its involvement in Sudan. It has continued to sell arms to the Sudanese government, some of which have been used to drive indigenous black southerners from their land to clear a path for oil pipelines and new oil fields.[3]

Despite Western attempts at sanctions and financial disincentives, China’s unconditional investment in Sudan has allowed human rights abuses to continue in Darfur and elsewhere in Sudan. Typically, similarly minded states as Sudan eventually find themselves without allies and without access to funds. China, however, has, in exchange for oil, provided the Sudanese government with money and weapons that are being used against the interests of Sudanese citizens. Patrick Keenan concludes that, “China…has no economic incentive to end the genocide.”[4]

China’s involvement in Zimbabwe tells a similar story. Zimbabwe’s president, Robert Mugabe, has a long history of oppressing the citizens of Zimbabwe. From banning homosexual acts to imprisoning political opponents, Mugabe’s human rights abuses do not require further explanation. It is instead worth mentioning the extent to which China’s policies have enabled said abuses.

Due to sanctions from the West, Zimbabwe developed a “Look East” policy in order to attract money. China has been a major financial partner of Zimbabwe, and now has substantial stakes in formerly state-owned firms.[5] China also lends money or invests in Zimbabwean firms in exchange for natural resources.[6] These deals provide much-needed funds to the government of Zimbabwe. The Chinese are also active in selling military aircraft to Mugabe.[7] China’s unconditional investments in Zimbabwe have enabled the Mugabe government to remain in power, thus allowing Zimbabwe’s human rights abuses to continue:

China’s support of Zimbabwe offers perhaps the starkest example of the social consequences of unconstrained financial support. Without China, there is almost no way that Zimbabwe’s president could have remained in power.[8]

China’s involvement in both Sudan and Zimbabwe offer clear examples of FDI making citizens worse off because of the implicit support of human rights abuses. Due to its interests in these countries, China has gone even further in supporting the governments of Sudan and Zimbabwe. As a member of the UN Security Council, China repeatedly blocked Western attempts for sanctions against Sudan, and it opposed Security Council discussion about a UN report that outlined Zimbabwe’s demolition campaign that left 700,000 people homeless.[9] China brings much-needed investment to many struggling African countries; however, when this investment enables human rights abuses, it is worth questioning the extent to which this approach to development is benefiting ordinary Africans.

Some negative outcomes have also resulted from China’s massive investments in African mines.[10] These include enabling poor governance, fostering corruption and inadequate working conditions.[11] Though these externalities are generally accepted by individuals on both sides of the debate, market advocates will contend that the net benefits to Africa, which includes new infrastructure and jobs, will outweigh the negative aspects of mining in Africa.[12] However, this claim should not be accepted too quickly. For instance, while getting these mines running and profitable requires much capital investment, it does not necessarily require social investment.[13] Therefore, while China will build roads and transportation links in order to extract Africa’s resources, social capital does not necessarily follow. Thanks to Chinese investment in Angola, the government spent most of its “redevelopment funds” on a railroad linking the main mining area with the port city of Benguela.[14] It is not clear that Angolans are better off because of this, as well as other, spending decisions. Democratic decisions have a better chance of benefiting the population; however, China’s willingness to fund the Angolan government, among others, removes the incentive for the government to democratize its behaviour.[15]

Nations with an abundance of natural resources often face a “resource curse” regardless of foreign involvement. The many problems associated with mineral wealth certainly cannot be attributed solely to Chinese and other foreign intervention, as these problems happen in isolation as well. The examples and arguments in this paper simply indicate that the Chinese approach to mining in Africa does not appear to solve the resource curse, and can even make it worse. Western NGOs, supported by governments, have recently initiated a significant debate about the relationship between mineral wealth and the detrimental effects on developing countries. Possible regulatory frameworks have been proposed that attempt to, “transform mineral wealth from a ‘curse’ into a vector of socio-economic development.”[16] China, however, is not only unlikely to join these efforts, but actually undermines the process by investing in almost any mine that is of economic interest.[17]

Natural resource extraction is also quite damaging to the environment. The problem, however, is that environmental degradation is often difficult to quantify. It is not always easy to prove that a population is worse off from environmental damage, yet it is an important part of a holistic development approach.

From African governments’ perspective, it is clear why the Chinese approach to mineral extraction would be favoured. Sahr Johnny, Sierra Leone’s ambassador to China, explains it succinctly:

We like Chinese investment because we have one meeting, we discuss what they want to do, and then they just do it…There are no benchmarks and preconditions, no environmental impact assessment. If a G8 country had offered to rebuild the stadium, we’d still be having meetings about it.[18]

There is certainly something to be said for the efficiency of moving a project ahead so quickly. Nevertheless, if a project contaminates a water source or pollutes the air, it becomes very difficult to argue that it benefits local citizens. This is not to suggest that the West’s development approach has been environmentally friendly and successful; the point is simply that the pro-business approach in Africa and around the world can be environmentally destructive and, thus, a detriment to the local population.

The Ok Tedi Mine, run by Broken Hill Proprietary (BHP), in Papua New Guinea is an extreme example. Over the years, millions of tons of mining waste were discharged into the river system, harming the environment and the health of many indigenous people. Some blame can be attributed to a lack of regulation, as it was found that BHP and the Papua New Guinea government made little attempt from the beginning of the project to properly understand the ecological impact.[19]

Lack of regulation is a common problem in developing countries, which is explained well by Nicholas Low and Brendan Gleeson:

There is pressure on states to introduce environmental regulation. But the governments of these states rapidly encounter the contradiction of their own precarious economic position in a competitive globalized world. There is a continual global auction of the right to pollute and to destroy local environments. The poorer the nation, the more dependent it is on capital inflow and the more it is forced to bid away its environment. This auction can only result in gross injustice among and within nations unless governments act to regulate not only corporations but also their own competition with one another.[20]

Thus, while bringing in some needed money to developing countries, corporate interest does not necessarily correlate with the betterment of citizens in developing countries. This is true not only of the environment. It is also worth questioning the extent to which foreign-owned businesses in developing countries lead to an improved economy.

Certainly a common argument among market advocates is that allowing businesses to work in developing countries will lead to jobs, tax revenue and economic growth. Moyo writes, “For Africa, besides the physical infrastructure, the growth and the jobs, there is the promise of poverty reduction [and] the prospect of a burgeoning middle class.”[21] Easterly reiterates that China, India, Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan went from developing to developed countries, “through the efforts of many decentralized agents participating in markets.”[22] These claims should be met with some caution. While opening up developing nations’ markets to foreign investors can certainly lead to long-term economic growth, the positive results can often be overstated.

As far as jobs are concerned, foreign-owned companies are sometimes hesitant to hire local workers. Chinese companies often primarily hire Chinese workers, thus not helping to solve the unemployment problems faced in developing countries. Even in constructing infrastructure, Chinese construction companies have used, “Chinese labour [that was] numbered in hundreds (sometimes thousands) while unemployed Africans were ignored.”[23] In 2005, total Chinese labour in Africa was estimated at 74,000.[24] Many of these jobs could instead be given to local citizens, which would be of greater benefit to Africans.

Opening up the market to cheap Chinese goods has also resulted in some problems for Africa’s manufacturing industry. Many African textile and clothing manufacturers have shed jobs by the tens of thousands because of an influx of inexpensive Chinese goods.[25] Chris Alden writes that opening up Africa’s market to Chinese goods was, “merely a new twist on an age-old story for Africa, the stripping of its resources by a foreign power to the benefit of a few fabulously wealthy leaders while ordinary Africans were left with a barren heritage.”[26] The availability of cheap goods is of some benefit to poor Africans, but the disadvantages must also be considered.

Tax revenue may also be a slightly naïve argument for opening up developing countries to FDI and multi-national corporations. Simply put, many developing nations do not possess the adequate institutions and income for tax revenue to significantly help develop these countries. Poor countries are trapped; they need tax revenue to build proper public institutions, but the lack of these institutions largely prevents the accumulation of significant tax revenue in the first place. In a 1995 study on tax revenue instability, Michael Bleaney, Norman Gemmell and David Greenaway found – unsurprisingly – that less developed countries have the highest tax revenue instability.[27]

Exactly how to stabilize tax revenue is a more complicated question that requires extensive literature of its own. Regardless, it remains to be seen how foreign-owned companies significantly increase the tax revenue of developing countries. These companies do pay taxes, but they are often at very low rates. Similar to inadequate regulation, host governments are often eager to attract foreign business, making it easier for corporations to avoid paying substantial tax. As one small example, Costa Rica attempted to attract the Intel Corporation in 1992. Intel was to build a semiconductor plant, and it weighed its options among many different countries in order to find the best deal. In order to finally attract Intel to Costa Rica, income taxes for the first eight years of business were exempted as well as a 50 percent exemption over the next four.[28] While providing some jobs and revenue to the country, Costa Rican officials admitted in hindsight that, “during the negotiations they had only an intuitive appreciation of the market failures they had to overcome and the externalities they might acquire.”[29]

Regardless of the corporate tax rate, the argument can be made that this approach will still raise tax revenue because of its effect on personal incomes. Governments in developing countries do not have a sufficient tax base to draw from, so increased employment and wages should help to solve the problem. While generally accurate, this argument needs to take into account the fact that companies are often reluctant to hire local workers, as noted above. Especially with respect to natural resource extraction, the profits also overwhelmingly benefit a small number of people and not the population in general. Related is the problem of capital flight, which is acknowledged by even the most staunch market supporters. It is extremely difficult for developing countries to retain a significant percentage of the wealth extracted by foreign-owned companies.

Assuming that companies hire locals and that wages are reasonable, income tax revenue can still be problematic for developing countries. It is not a given that developing countries will benefit from taxes, even under the best FDI circumstances. Developing countries are hampered by many costs in setting up a proper tax policy. These include administrative costs, compliance costs, efficiency costs and political costs.[30] It is of course in these countries’ long-term interests to eventually set up functioning tax regimes; however, it is not always simple to do so.

The importance of reducing inequality in countries has been noted by many academics. A well-known argument can be found in The Spirit Level, by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett. In their thirty years of research, the two authors found that both rich and poor are worse off in unequal societies and that many problems – health, violence, drugs, obesity, mental illness, etc. – are more likely to occur in a less equal society.[31] It can thus be said with some certainty that it is in developing countries’ interest to promote a more egalitarian country. If redistributive taxation is to play a role in making society more egalitarian, it is worth questioning its effectiveness. In developed countries with effective institutions and high incomes, redistributive taxation is largely effective. In developing countries, however, it does not work as well. As noted by Richard Bird and Eric Zolt, “Taxes, particularly the personal income tax, have done little if anything to reduce inequality in developing countries.”[32] In low-income countries, tax revenue only accounts for 18.3% of GDP, while 29.4% of GDP in high-income countries.[33] Progressive tax systems are much more difficult to come by in developing nations. This is to say nothing of the negative consequences that multinational corporations can have on equality in society; it is simply to make the point that it is more difficult in developing countries to improve citizens’ well-being through tax revenue, despite what market advocates might argue.

Finally, the FDI approach must be critically analyzed through the lens of economic development. Does opening up a country’s markets to FDI lead to positive economic growth? It would seem obvious that it does; however, this is not always the case, as many years of Structural Adjustment Programs have shown.

The Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) has recently put emphasis on such an approach. CIDA’s countries of focus are largely ones with natural resource wealth, and CIDA is now active in using private companies in its development plans. In speaking about natural resources and mining companies on September 29, 2011, Bev Oda said, “Working in partnership with the private sector, these resources can contribute to poverty reduction in many of these countries and improve the standard of living for their populations.”[34] New pilot projects announced by CIDA in September effectively mean that CIDA will subsidize Canadian mining companies abroad.[35] Canadian government support for mining companies is extremely high, despite a failed 2010 private member’s bill that would have required more accountability and regulation from Canadian mining companies abroad.

Canadian mining companies have also grown enormously over the years. Canadian mining investments in Africa have increased from a quarter billion dollars in 1989 to $20 billion in 2010.[36] The question that then arises is if this increased investment has benefited Africans. The consensus is far from clear. Some individuals, including industry advocates, will argue that economic growth has in fact occurred due to mining companies’ involvement.[37] Others will admit that economic growth has not correlated with the rise of FDI in Africa, but they maintain the benefit of this approach and that economic stagnation occurs because of poor government capacity and governance issues.[38]

Other observers have found that mining has had a dismal record to date in poverty reduction.[39] Foreign-owned companies extracting natural resources from Africa does not easily result in economic growth and poverty alleviation. Michael Ross had a similar conclusion in an influential 2009 report for Oxfam America, writing, “If growth is good for the poor, oil and minerals exports are bad for growth – and hence, bad for the poor.”[40]

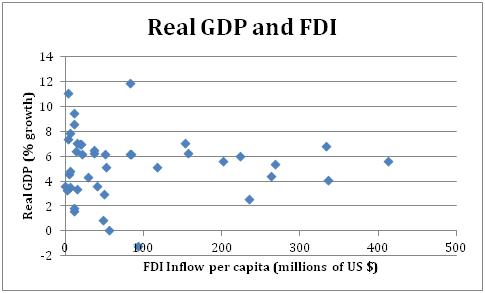

When looking at the growth of FDI in Africa and the GDP numbers across the continent, there appears to be little correlation. FDI and corporate involvement in Africa has grown substantially in recent years, but economic growth has not always followed. Yao Graham recently wrote about the lack of development and improvement in the lives of Africans despite record profits by mining companies.[41] The massive profits of these companies do not stay in Africa. Furthermore, a World Bank study found that GDP growth was negative in countries where mining was a “dominant” or “critical” industry.[42] It is reasonable to conclude that claims of poverty reduction and economic growth are overstated when speaking of corporate influence in Africa. It must not be accepted too quickly that economic growth will result from increased FDI and corporate involvement.

The following graph further illustrates this point. FDI inflow per capita is compared with real GDP growth for the most recently available data in 42 African countries.

Figure 1: Correlation Between Real GDP and FDI Inflow in 2010[43]

As FDI increases to African countries, real GDP tends not to increase. No real correlation can be deducted from the data. This certainly runs contrary to market advocates’ claim that economic growth will be achieved through increased FDI.

In summary, the Chinese approach to development – one of massive FDI – should be met with some justifiable hesitation. It leads to some negative externalities and does not necessarily solve the development issues that market-advocates often contend. The Chinese approach has been shown to enable and preserve human rights abuses; it does not provide adequate social capital or solve the resource curse; it can be quite damaging to the environment; and, it does not necessarily create jobs, tax revenue and economic growth. This section is not meant to be a defeatist argument against FDI. Instead, it has shown that arguments in favour of the Chinese approach in Africa can overstate the benefit this approach has, since it can actually do more harm to Africans than good.

Other Market Approaches

In addition to FDI, a number of other approaches have been proposed as effective market-based alternatives to foreign aid. For the purposes of this paper, two main approaches will be analyzed: trade and microfinance. The goal will again be to show the limit of these approaches in improving the lives of the poor.

Trade should not be presented as the antithesis to aid. These two approaches to development are not mutually exclusive and are both important aspects of a well-rounded approach to poverty alleviation. Nevertheless, Moyo argues that it is trade that must be addressed by the West, not aid.[44] She, along with other authors, does admit that trade is not the lone solution to Africa’s problems; however, it plays an important part. Nonetheless, it is worth noting the limits that trade has in development.

Although there are notable exceptions, it is difficult to deny the strong correlation between a country’s trade freedom and its economic prosperity. The most developed countries in the world are ones that widely engage in trade. This does not, however, mean that liberalizing its trade policy would benefit each African country. A notable consequence of integrating fully in the world market is that these countries are then vulnerable to fluctuations in the world market. There is a reason that African countries were less affected than developed countries by the 2008 financial crisis – they were less integrated and thus less reliant on international trade. Increasing trade may indeed provide some economic growth to poor countries; however, it also makes them more vulnerable to economic shocks around the world. For impoverished nations, a global recession would be especially devastating. It would result in less capital flowing into Africa, which could mean less food and higher unemployment.

This paper is not making the argument that Africa should avoid trade, although some authors have argued that Africa does “overtrade.”[45] Instead, the point is that the risks of international trade need to be considered alongside the benefits. Trade is generally understood as positive for the economy, but Africa must not be compared in the same context as developed countries. While increased trade is good for Canada’s economy, African countries need to be understood by their own unique circumstances.

One of these unique circumstances is the arbitrary borders of African nations. European nations evolved fairly naturally, and the borders today somewhat represent the historical, religious, cultural and linguistic differences of European peoples. The same cannot be said for African nations. The borders today are a reflection of Africa’s colonial past. European nations arbitrarily drew up the borders in Africa, which did not consider historical, religious, culture or linguistic realities. Africa is left with fragmented states with little sense of unity.

Instead of one of these states engaging in international commerce, it makes sense to first develop more intra-African trade. Regional trade within Africa will work better when considering the cultural and ethnic realities of Africa, which are not defined by the nation-state. Intra-African trade is still very limited, however. As a percentage of total trade for sub-Saharan African countries, intra-African trade accounts for only 7.5% on average.[46] European Union (EU), Southern Cone and NAFTA countries do much more regional trade as a percentage of their total trade. The most developed countries tend to rely more on regional trade than international trade. African countries, however, do not follow this trend. In 1998, exports to the EU accounted for 40% of African exports.[47]

Beyond economic growth, it is worth expanding intra-African trade for two reasons. First, regional integration might reduce political and military tensions between countries.[48] The more two countries benefit each other economically, the less likely they are to fight one another. With strong trade links, war would not be a means of obtaining more economic wealth; it would be a detriment to both economies. Schiff and Winters further examine the role of trade in enhancing peace in a 1998 article.[49] Secondly, regional integration can assist in bringing about important reforms.[50]

Despite the benefits of increased intra-African trade, it is not easy to make happen. Three main obstacles stand in the way of increasing regional integration in Africa: insufficient infrastructure, mismanagement of economic policies and internal political tensions.[51] These problems each require complex solutions that need to be solved before trade can realistically increase. Foreign aid can play an important part of the solutions, especially with respect to insufficient infrastructure.

In speaking of international trade, it is important to recognize the tremendous trade imbalance already present throughout the world. With respect to Africa’s trade with China, Piet Konings writes that, “the balance of trade currently favours China.”[52] The balance of trade with the West is no different. The result of a trade imbalance is often high debt for the net importing country. Over the long-term, an increased debt can have wide-ranging economic impacts. Needless to say, it is in Africa’s interest to avoid furthering its trade imbalance.

It can be argued that the current world trade system also reinforces neo-colonial relationships. The more that Africa engages in international trade, the more it is exploited by its former, as well as some new, colonizers. Market advocates often argue against foreign aid because it leaves countries dependent; however, a neo-colonial economic system leaves African countries exploited by, and dependent on, the neo-colonial powers. Whether the economic benefits from increased access to the world markets outweighs the exploitative nature of the neo-colonial relationships is quantifiably impossible. Nevertheless, these considerations are important in determining the appropriate approach to Africa’s development.

In addition to trade, microfinance has gained recent popularity as a means of financially empowering the poor. Microfinance provides a broad range of services, but typically involves providing financing to low-income individuals. Microfinance has been made popular due to organizations such as the Grameen Bank, which won Muhammad Yunus – Grameen Bank’s founder – the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006.

On the surface, microfinance has been tremendously successful. Repayment of loans averages between 95 and 98 percent – higher than student loan and credit card repayment in the United States.[53] Recipients, who are primarily women, use the loans to start or expand small businesses. As the women are able to bring in more money, they can then send their children to school and provide improved nutrition to their families.

Poverty reduction is the clear stated goal of microfinance, and in this it has succeeded. While its impact on GDP is difficult to observe, microfinance’s poverty reduction effects are noticeable. In rural Bangladesh, microfinance participants’ poverty decreased by three percent annually, more than half of which can be directly attributed to microfinance programs.[54] Microfinance also has spillover effects into the larger community. It can account for 40 percent of the overall reductions in moderate poverty.[55] For extreme poverty, the results are even higher.

It is often difficult to measure the effects that microfinance has on a population. However, Khandker’s in-depth analysis of microfinance in Bangladesh results in clear conclusions. “Microfinance continues to reduce poverty among poor borrowers and within the local economy…It raises per capita household consumption for both participants and nonparticipants.”[56] Of course, the results do not necessarily translate to all countries of the world. A variety of factors – cultural, political or economic – may prevent microfinance from being as successful in other developing countries. Nevertheless, it is difficult to deny the positive impact that microfinance has had on the micro level.

Despite its success in poverty reduction, microfinance has its limitations. It is not the panacea to underdevelopment. Microfinance cannot train doctors, build schools or enable good governance. Many of these wider factors require an influx of money in the form of foreign aid. In short, microfinance succeeds at the micro level, but is not a contributing factor to development at the macro level.

In addition, it has been found that microfinance can reinforce existing hierarchies and inequalities. Instead of empowering the poorest of society, microfinance in Cajamarca, Peru strengthened the existing power structure in the community.[57] Other critiques have been levied against microfinance, including poor working conditions, low labour standards and high interest rates. Most of these criticisms are circumstantial and are not general critiques of the microfinance model. The important limitations of microfinance are at the macro level. Microfinance needs to be understood as one part of the development strategy and not the universal solution.

In addition to trade and microfinance, market advocates have proposed a number of other market-based strategies. Due to the limits of this paper, these have not been included. In short, these other strategies, such as selling bonds or privatizing government industries, are simplistic and incomplete approaches to economic development. Selling bonds is somewhat unrealistic, as international capital markets are extremely expensive for the poor to borrow from. Moyo also argues that these strategies would help end corruption, which is a major hindrance to development.[58] However, market-based strategies do not necessarily end corruption since it can – and does – still occur in licensing and other areas.

In summary, many market-based approaches have been put forward in addition to FDI. Among these approaches are trade and microfinance. Though they are tools with much potential, their limitations need to be understood in order to approach development in an effective and holistic manner. Trade within Africa is more in the interest of Africans than international trade, though it is difficult to implement. International trade can leave developing countries vulnerable to the fluctuations of the world market, increase developing countries’ debt and perpetuate neo-colonial power relationships. Next, microfinance can be a useful tool for poverty reduction. Its major limitation is that it is unable to provide larger development necessities, such as infrastructure and professionally trained individuals.

Conclusion

There has been a recent trend in academic and popular literature promoting the benefits of the capitalist market for helping to develop the world’s poorest nations. Whether in addition to, or replace of, foreign aid, market-advocates contend that this strategy is the most effective in assisting the world’s poor. This paper has sought to address the limitations of market-based strategies, such as FDI, trade and microfinance.

FDI has enabled human rights abuses; it is harmful to the natural environment, specifically with respect to mining; it does not necessarily result in investment of social capital; it does not always lower unemployment; it may not result in increased tax revenue; and, its impact on economic growth is overstated. Trade leaves developing countries vulnerable; it often results in a significant trade imbalance for developing countries; it can perpetuate neo-colonial power relationships; and, it is difficult to trade regionally in Africa, which would be of greater benefit. Microfinance has been relatively successful; however, it does not provide the necessary macro tools of development.

The paper has viewed development not solely through the lens of economic numbers. Since the goal of development is to improve the quality of life of those living in poverty, this paper has analyzed development in a nuanced way. The conclusions of the paper are varied and not easily quantifiable. In short, market-based approaches to development are simplistic, and their limitations need to be weighed against the benefits that these approaches do possess. Better understanding the positive and negative aspects of every development strategy will eventually lead to improved results for the poorest individuals of the world.

Bibliography

African Development Bank Group. “African Statistical Yearbook.” African Development Bank Group. 2009. Accessed December 5, 2011. http://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/African%20Statistical%20Yearbook%202009%20%2000.%20Full%20Volume.pdf.

Alden, Chris. China in Africa. New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2007.

Bebbington, Anthony, Leonith Hinojosa, Denise Humphreys Bebbington, Maria Luisa Burneo and Ximena Waraars. “Contention and Ambiguity: Mining and the Possibilities of Development.” Development and Change 39, no. 6 (2008): 887-914.

Bird, Richard M. and Eric M. Zolt. “Redistribution via Taxation: The Limted Role of the Personal Income Tax in Developing Countries.” UCLA Law Review 52, no. 6 (2006): 1627-1695.

Bleaney, Michael, Norman Gemmell and David Greenaway. “Tax Revenue Instability, with Particular Reference to Sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of Development Studies 31, no. 6 (August 1995): 883-902.

Canadian International Development Agency. “Minister Oda announces initiatives to increase the benefits of natural resource management for people in Africa and South America.” Accessed December 5, 2011. http://www.acdi-cida.gc.ca /acdi-cida/ACDI-CIDA.nsf/En/CAR-929105317-KGD?OpenDocument.

Carmody, Pádraig. “An Asian-Driven Economic Recovery in Africa? The Zambian Case.” World Development 37, no. 7 (July 2009): 1197-1207.

Coe, David T. and Alexander W. Hoffmaister. “North-South Trade: Is Africa Unusual?” Journal of African Economies 8, no. 2 (1999): 228-256.

Easterly, William. The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good. New York: The Penguin Press, 2006.

Engler, Yves. “An Abduction in Niger: Canada, the UN and Canadian Mining.” Canadian Dimension. January 31, 2009. http://canadiandimension.com/articles/2170.

Fernando, Jude L. Microfinance: Perils and Prospects. Florence, KY: Routledge, 2005.

Graham, Yao. “The roots of inequality: Mining profits soar, but Africans still poor.” Embassy. November 14, 2011. http://www.embassymag.ca/dailyupdate/view/153.

Grameen Foundaiton. “Microfinance Basics.” Accessed December 9, 2011. http://www.grameenfoundation.org/what-we-do/microfinance-basics.

Hawkins, Tony. “Scepticism Pervades China’s Trade Finance Deals with Zimbabwe.” Financial Times, June 28, 2006.

Hilsum, Lindsey. “The Chinese are Coming.” New Statesman. July 4, 2005.

Human Rights Watch. “You’ll Be Fired if You Refuse: Labor Abuses in Zambia’s Chinese State-owned Copper Mines.” Human Rights Watch. November 2011. Accessed December 2, 2011. http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/zambia1111ForWebUpload.pdf.

Keenan, Patrick J. “Curse or Cure? China, Africa, and the Effects of Unconditioned Wealth.” Berkeley Journal of International Law 27, no. 1 (2009).

Khandker, Shahidur R. “Microfinance and Poverty: Evidence Using Panel Data from Bangladesh.” The World Bank Economic Review 19, no. 2 (2005): 263-286.

Konings, Piet. “China and Africa: Building a Strategic Partnership.” Journal of Developing Societies 23, no. 3 (2007): 341-367.

Longo, Robert. “Economic Obstacles to Expanding Intra-African Trade.” World Development 32, no. 8 (2004): 1309-1321.

Low, Nicholas and Brendan Gleeson. “Situating Justice in the Environment: The Case of BHP at the Ok Tedi Copper Mine.” Antipode 30, no. 3 (1998): 201-226.

Moran, Theodore H. Harnessing Foreign Direct Investment for Development: Policies for Developed and Developing Countries. Washington: Center for Global Development, 2006.

Moyo, Dambisa. Dead Aid: Why Aid is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 2010.

New Africa. “In Brief: Zimbabwe.” New African (July 2006): 27.

Pegg, Scott. “Mining and Poverty Reduction: Transforming Rhetoric to Reality.” Journal of Cleaner Production 14, no. 3-4 (2006): 376-387.

Ross, Michael. Extractive Sectors and the Poor: An Oxfam America Report. Boston: Oxfam America.

Rupp, Stephanie. “Africa and China: Engaging Postcolonial Interdependencies.” In China into Africa: Trade, Aid, and Influence, edited by Robert I. Rotberg, 65-86. Cambridge: Brookings Institution Press, 2008.

Schiff, Maurice and L. Alan Winters. “Regional Integration as Diplomacy.” World Bank Economic Review 12, no. 2 (1998): 271-295.

Tull, Denis M. “The Political Consequences of China’s Return to Africa.” In China Returns to Africa: A Rising Power and a Continent Embrace, edited by Chris Alden, Daniel Large and Ricardo Soares de Oliveira, 111-128. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

Wilkinson, Richard and Kate Pickett. The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone. Toronto: Penguin Books, 2010.

[1] Dambisa Moyo, Dead Aid: Why Aid is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa (Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 2010), 47.

[2] Patrick J. Keenan, “Curse or Cure? China, Africa, and the Effects of Unconditioned Wealth,” Berkeley Journal of International Law 27, no. 1 (2009), 20.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Keenan, Curse or Cure,” 21.

[5] “In Brief: Zimbabwe,” New African (July 2006): 27.

[6] Tony Hawkins, “Scepticism Pervades China’s Trade Finance Deals with Zimbabwe,” Financial Times, June 28, 2006, 13.

[7] Keenan, “Curse or Cure,” 24.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Denis M. Tull, “The Political Consequences of China’s Return to Africa,” in China Returns to Africa: A Rising Power and a Continent Embrace, ed. Chris Alden et al. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 122.

[10] This is, of course, not limited to China. The point here is simply to show the problems associated with FDI in general.

[11] Human Rights Watch, “You’ll Be Fired if You Refuse: Labor Abuses in Zambia’s Chinese State-owned Copper Mines,” Human Rights Watch, November 2011, accessed December 2, 2011, http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/zambia1111ForWebUpload.pdf.

[12] Moyo, Dead Aid, 110.

[13] Stephanie Rupp, “Africa and China: Engaging Postcolonial Interdependencies,” in China into Africa: Trade, Aid, and Influence, ed. Robert I. Rotberg (Cambridge: Brookings Institution Press, 2008), 76.

[14] Keenan, “Curse or Cure,” 19.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Tull, “Political Consequences,” 124.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Lindsey Hilsum, “The Chinese are Coming,” New Statesman, July 4, 2005, 18.

[19] Nicholas Low and Brendan Gleeson, “Situating Justice in the Environment: The Case of BHP at the Ok Tedi Copper Mine,” Antipode 30, no. 3 (1998): 215.

[20] Low and Gleeson, “Situating Justice in the Environment,” 215.

[21] Moyo, Dead Aid, 112.

[22] William Easterly, The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good (New York: The Penguin Press, 2006), 27.

[23] Chris Alden, China in Africa (New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2007): 3.

[24] Piet Konings, “China and Africa: Building a Strategic Partnership,” Journal of Developing Societies 23, no. 3 (2007): 358.

[25] Alden, China in Africa, 3.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Michael Bleaney, Norman Gemmell and David Greenaway, “Tax Revenue Instability, with Particular Reference to Sub-Saharan Africa,” Journal of Development Studies 31, no. 6 (August 1995): 883-902.

[28] Theodore, H. Moran, Harnessing Foreign Direct Investment for Development: Policies for Developed and Developing Countries (Washington: Center for Global Development, 2006), 31.

[29] Ibid., 31

[30] Richard M. Bird and Eric M. Zolt, “Redistribution via Taxation: The Limted Role of the Personal Income Tax in Developing Countries,” UCLA Law Review 52, no. 6 (2006): 1627-1695.

[31] Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone (Toronto: Penguin Books, 2010).

[32] Bird and Zolt, “Redistribution,” 1694.

[33] Ibid., 1654.

[34] “Minister Oda announces initiatives to increase the benefits of natural resource management for people in Africa and South America,” Canadian International Development Agency, accessed December 5, 2011, http://www.acdi-cida.gc.ca/acdi-cida/ACDI-CIDA.nsf/En/CAR-929105317-KGD?OpenDocument.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Yves Engler, “An Abuduction in Niger: Canada, the UN and Canadian Mining,” Canadian Dimension, January 31, 2009, http://canadiandimension.com/articles/2170/.

[37] Pádraig Carmody, “An Asian-Driven Economic Recovery in Africa? The Zambian Case,” World Development 37, no. 7 (July 2009): 1197-1207.

[38] Anthony Bebbington, Leonith Hinojosa, Denise Humphreys Bebbington, Maria Luisa Burneo and Ximena Waraars, “Contention and Ambiguity: Mining and the Possibilities of Development,” Development and Change 39, no. 6 (2008): 891.

[39] Scott Pegg, “Mining and Poverty Reduction: Transforming Rhetoric to Reality,” Journal of Cleaner Production 14, no. 3-4 (2006): 376.

[40] Michael Ross, Extractive Sectors and the Poor: An Oxfam America Report, (Boston: Oxfam America).

[41] Yao Graham, “The roots of inequality: Mining profits soar, but Africans still poor,” Embassy, November 14, 2011 http://www.embassymag.ca/dailyupdate/view/153.

[42] Pegg, “Mining and Poverty Reduction,” 376.

[43] Data obtained from African Development Bank Group, “African Statistical Yearbook,” African Union, 2009, accessed December 5, 2011, http://www.africa-union.org/root/UA/Annonces/African% 20Statistical%20Yearbook%202009%20-%2000.%20Full%20Volume.pdf.

Two outliers – Angola and Equatorial Guinea – were removed from the chart. Angola’s FDI inflow per capita was -88.1 (million US $) and its real GDP growth was 21.1%. Equatorial Guinea’s FDI inflow per capita was 3,402 (million US $) and its real GDP growth was 17.7%. Including these two outliers would not change the conclusion of the correlation; removing them simply makes the graph more readable.

[44] Moyo, Dead Aid, 119.

[45] David T. Coe and Alexander W. Hoffmaister, “North-South Trade: Is Africa Unusual?,” Journal of African Economies 8, no. 2 (1999): 228-256.

[46] Robert Longo, “Economic Obstacles to Expanding Intra-African Trade,” World Development, 32, no. 8 (2004): 1309-1321.

[47] Ibid., 1317.

[48] Ibid., 1312.

[49] Maurice Schiff and L. Alan Winters, “Regional Integration as Diplomacy,” World Bank Economic Review 12, no. 2 (1998): 271-295.

[50] Ibid., 1312.

[51] Ibid., 1317.

[52] Konings, “China and Africa,” 343.

[53] “Microfinance Basics,” Grameen Foundation, accessed December 9, 2011, http://www.grameenfoundation.org/what-we-do/microfinance-basics.

[54] Shahidur R. Khandker, “Microfinance and Poverty: Evidence Using Panel Data from Bangladesh,” The World Bank Economic Review 19, no. 2 (2005): 284.

[55] Khandker, “Microfinance and Poverty,” 284.

[56] Ibid., 285.

[57] Jude L. Fernando, Microfinance: Perils and Prospects (Florence, KY: Routledge, 2005), 145.

[58] Moyo, Dead Aid,

—

Written by: Graeme Esau

Written at: University of Ottawa

Written for: Stephen Brown

Date written: December 2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Preventing Apocalyptic Futures: The Need for Alternatives to Development

- Gendered Implications of Neoliberal Development Policies in Guangdong Province

- Transnational Corporations, State Capacity and Development in Nigeria

- Modernities for ‘Alternatives to Development’: Vietnamese Colonial Modernity

- Examining and Critiquing the Security–Development Nexus

- The Use of “Remote” Warfare: A Strategy to Limit Loss and Responsibility