“Does growing Chinese involvement in Latin America constitute evidence of a ’China threat’ which threatens vital American interests?”

CHAPTER ONE: Introduction to the ‘China Threat’ theory

Washington has long asserted that it is the sole overlord of the Western Hemisphere and will not tolerate any perceived outside interference in the region’s affairs. The Monroe Doctrine of 1823 stated that Latin America and the Caribbean were not to be considered by the European imperialist powers as areas ripe for colonization. Since then, the region has been under the political, cultural and economic leadership of the United States of America, despite resurgent colonial interest from Spain, and laterally, the attempted ideological infusion of the Soviet Union.

Fast forward 178 years since the signing of the treaty, and there is a new potential adversary for the United States in the region. Chinese Premier Jiang Zemin’s 2001 visit to Latin America signified a new Chinese interest in the continent. He promised support, investment, and the deepening of trade links, as a growing China sought natural resources, political allies, and new markets for its rapidly expanding industrial sector. While more attention has been paid to China’s burgeoning relationship with African states, China has quietly built up its presence in Latin America, and the United States has begun to take notice and worry about the implications of this rise.

Why China?

However, before we get to details about Chinese involvement in Latin America, a simple question has to be asked first: Why the American pre-occupation with China? The answer is the concept of the ‘China threat’ theory, a theory which is as elusive as it is controversial. In this chapter we will examine parts of the China threat theory in an attempt to explain why the U.S feels so anxious about the rise of the PRC, and we will discuss how the theory applies to Chinese involvement in Latin America.

The China threat in theory: ‘othering’

In international politics, quite often we define who we are, by who we are not. This process, known as othering, is endemic in international politics as a whole, and is particularly prevalent in the thinking of the United States. Pan notes that “after the demise of the Soviet Union, the vacancy of other was to be filled by China, the ‘best candidate’ the United States could find in the post-Cold War, unipolar world.” [1] Without something to project against, the U.S loses some of its own sense of identity, as defender of the free world and chief exponent of democracy. Pan goes on to argue therefore that “the ‘truism’ that China presents a growing threat is not so much an objective reflection of contemporary global reality, per se, as it is a discursive construction of otherness that acts to bolster the hegemonic leadership of the United States in the post-Cold War world.” [2] From this we understand two things – that any ‘China threat’ is a matter of perspective, and that part of the United States consciousness needs to believe in the reality of this threat to justify its own behaviour. Essentially, this means that “so long as the United States continues to stake its self-identity on the realization of absolute security, no amount of Chinese cooperation would be enough,”[3] suggesting the potential permanence of the American reaction to the rise of China.

The Importance of Potential

Another key element in the discussion of China as a threat is potential. This is important for the realist argument, which deals only with capabilities, rather than intentions. China’s potential is multi-faceted, political, economic, and military, and it is the realisation of this potential that worries American policy makers. Indeed, “much of today’s alarm about the “rise of China” resolves around the phenomenal development of the Chinese economy during the past twenty-five years.”[4] An increasing number of American scholars are focusing on how this rise might manifest itself. A congress report found that “even if its international outreach is entirely benign and centred on economic growth, the PRC’s potential to expand quickly to consumption and production levels comparable to those of the United States presents profound challenges to American and global interests.”[5] The prescription then, is dealing with China as could be, rather than dealing with it as is. The obvious flaw in this reasoning is that political forecasting is notoriously unreliable, and dealing with capabilities often gives undue authority to speculation. Subsequently, within reason, the potential of a ‘China threat’ can be whatever you want or need it to be.

The China threat in practice

Latin America represents a good example of the China threat realised in practice. As Chinese involvement in the region is at a very early stage, analysis tends to focus on its goals which are described as “economic, geostrategic, and irredentist”[6] and its capabilities, with an eye to the worst possible repercussions for the U.S because Beijing is portrayed as “unhappy with the United States’ role as the sole global superpower,”[7] and many conclude that it “ultimately intends a direct challenge to U.S global power.”[8] In practice, this means “Beijing’s growing political and economic presence is increasingly perceived by the United States as a serious intrusion.“[9] This intrusion will not be ignored by Washington because it will be viewed as a fundamental challenge to its hegemony.

The United States is worried that the presence of China will destabilize the region “by presenting an alternative political and economic model – rapid economic growth and modernization alongside political authoritarianism.”[10] As it views itself as the defender of Democracy, Washington is irate that China presents a ‘no strings attached’ approach to Latin American trade and resource dealings, because it “undermines the U.S agenda to advance political reform, human rights and free trade in the region.”[11] The hegemon is not interested in alternatives to its rule – since the Monroe Doctrine, Latin America has remained “firmly within its sphere of influence.”[12] There are specific issues that Washington has genuine fears about, in particular, the rise of China is seen as complicating U.S efforts to “control illegal immigration, weapons shipments, the drug trade and money laundering because China is cooperating with Latin countries that are not especially friendly toward those efforts.”[13] The accuracy and validity of the claim is questionable but the fear behind the speculation is genuine. China is also often judged by the company it keeps, in particular it comes under fire for its close political and economic relationships with American adversaries old and new, Cuba and Venezuela, who “may try to use the Chinese alternative to challenge U.S hegemony.”[14] China may find itself guilty by association. The USA has a tendency to see things in black and white – to paraphrase, you are either with them, or against them.

Current Literature on the subject

Literature on the subject varies in quality, scope, and focus. Aspects of China’s rise are very often dealt with in an alarmist fashion by many authors, who view China as posing a direct threat to the hegemony and security of the United States. This approach, typified by the likes of Gertz (2002), Hutton (2007) and Navarro (2007) succeeds in portraying China as malicious, and presumes that China’s intentions are both known and fixed. On the other side, many articles and books that discuss China’s rise in wholly positive terms such as He & Qin (2006), Jisi (2005), Pan (2004), and Pollack (2004) often find the need to be defensive in their portrayal of China’s rise, pre-empting the anti-China backlash by a pro-active policy of placating it. Similarly, those authors such as Agatellio (2005), Devlin, Estevadeordal, & Rodríguez-Clare (2006), Domínguez (2006), who deal with the direct economic and political impact of China on Latin America cannot help but assess what impact this relationship has on the United States. This seems to be evidence of the emergence of a true triangular relationship, because the involvement of China in Latin America has intrinsic implications for the United States.

A lot of the literature has been commissioned and cannot be considered politically neutral, such as works by Blair and Hills (2007) for the Council of Foreign Relations, Dumbaugh (2006) for the CRS Report for Congress, and the Congressional Research Library of Congress (2008) report prepared for the United States senate. Similarly due to a lack of genuine academic freedom in China, often breaking news on the subject can only be attained through state owned papers such as Xinhua and the People’s Daily. This adds to the partisan and schizophrenic nature of literature on the subject and isn’t conducive to synthesis. Another major problem with the literature on the subject is that it only very rarely grasps the concept that both where China is now, and where China will be in the future are important. Too many authors such as Roett & Paz (2008) dismiss China’s activities in Latin America as limited and inconsequential, but yet more authors such as Lafargue (2006) and Collins & Ramos-Mrosovsky (2006) deal with Chinese intentions in such a fatalistic manner as if intentions were both known and set in stone. This gap between assessing China’s involvement in Latin America present and future is not often successfully bridged.

Approach and outline

In this essay, we ask the question; ‘Does Growing Chinese Involvement in Latin America constitute evidence of a ‘China threat’ which threatens vital American interests?’ My approach will adhere to the idea that there is a triangular relationship between China, the U.S., and Latin America, and deal with Latin America as an active element in the relationship, rather than treating it like the chessboard of the great powers. While this thesis cannot claim to be free of opinion or without bias, it is not being written for the benefit of any institution, government, publisher, or organization, and therefore its findings are not commissioned. I intend to deal thematically with the major aspects of China’s activities in Latin America as it is the best way to break down such a multi-faceted area of international politics.

I have been careful to use sources from a variety of different political persuasions to give a balanced impression of some highly emotive issues. However, ‘China threat’ literature will be treated as the prevailing standard which is to be engaged and questioned and this thesis will put effort into valuing reasoned analysis ahead of hypothesis and conjecture. A recurring theme in this thesis will be the concept of ‘perception’, particularly as the ‘China threat’ can in many cases prove to be self fulfilling. As perception is important, and objective reality is ‘unattainable’, each chapter will end with a nuanced synthesis of perception and subjective reality.

Although in this essay ‘Latin America’ will be treated sometimes as a singular unit, in reality, most focus will be on certain countries. Cuba and Venezuela represent perceived ideological allies of the PRC, Mexico and Columbia represent contemporary US allies in the region, Brazil and Ecuador represent vast new resource markets for China, and Haiti and Paraguay represent the most interesting cases when it comes to the recognition of Taiwan.

After this introduction, the second chapter will examine what China wants from Latin America. We will examine China’s hunger for oil and other resources. We will also investigate the diplomatic tussle for recognition between the PRC and the ROC (Taiwan) amongst the states of Latin America and the Caribbean and ask what this could mean for the United States.

The third chapter will detail the growing political and economic linkages between China and the countries of Latin America, in an attempt to illustrate the depth of trans-pacific cooperation that is occurring. We will again focus on what the possible implications could be for the United States of the strengthening of Sino-Latin American ties.

The fourth chapter will deal with the possibility of a Chinese led military alliance in Latin America, and examines how this may come to threaten the United States. We will deal also with the more specific case of the Panama Canal, where many in the U.S. fear the growing visible presence of the Chinese.

The conclusion should hopefully tie all these ideas together and provide conciliatory and balanced analysis to help us determine whether U.S interests are in fact threatened by the emergence of China as a power in the Western hemisphere.

CHAPTER TWO: China’s Goals in Latin America

In this chapter, we examine China’s two key policy goals in Latin America. First we will examine China’s drive for acquisition of natural resources from a fertile new market in order to underpin its growth. Secondly, we will examine the PRC’s efforts to remove the ROC government on Taiwan by courting its political allies in Latin America and the Caribbean.

China’s thirst for resources

With the fastest growing large economy in the world, China’s hunger for resources is extraordinary, its “oil demand increased by more than 55 percent between 2000 and 2006.”[15] Despite possessing great oil reserves of its own, for the first time ever, China “became a net importer of oil in 1993 – and its energy demands are expected to continue increasing at an annual rate of 4–5 percent through at least 2015, compared to an annual rate of about 1 percent in industrialized countries.”[16] Professor of Strategy at the National War College in Washington Cynthia Watson notes that “China has a targeted need to find energy resources,” [17] because the subsequent shortfall in demand versus consumption has to be made up by the acquisition of resources from external sources. For the most part, much of this shortfall has been made up by importing from Russia, and importing from OPEC allies such as Oman.

However, as in any business, diversification is key to protect yourself from the turbulence of the open market and “volatility in the Middle East combined with growing uncertainty in oil-rich neighbouring countries such as Russia have led China to seek investment opportunities in other regions, particularly Africa and Latin America.” [18] While it would be a caricature to describe China as insular, particularly since the reforms of Deng Xiaoping, it would be fair to summarise that its forays into Africa and the Americas represent its first real extra-regional political excursions. As its thirst for resources is not going to be quenched in the near future, “China can be expected to continue its determined quest for hydrocarbons and … will be venturing into the United States’ traditional zones of influence.” [19] This is the crucial point of discussion from the point of viewpoint of this essay. While China has made many more seemingly significant steps in its relationship with Africa, for the most part, the countries with whom it deals are not U.S allies. The table below shows where China imports its oil from.

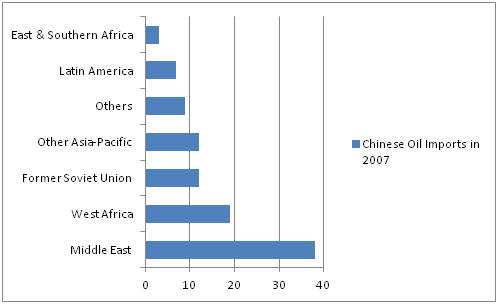

Table 1: Percentage of Chinese Oil Imports in 2007 [20]

Although currently China receives only 7% of its oil imports from Latin America, the region “with 9.7% of world oil reserves, could potentially enable the PRC to meet its projected energy requirements. Not surprisingly, therefore, China has become the second largest importer of Latin American oil, after the United States. In fact, since 2001, China’s appetite for Latin American oil has grown at least ten-fold.”[21] At this stage, much of the discussion is of the potential importance of the region to China, and the potential depth of China’s involvement. To put this potential in context however, we have to examine the current Chinese involvement.

Chinese energy security strategy

The first point we should make clear however, is that ‘China’ is not a unitary actor, and the major oil companies in China, while sharing national goals of bringing steady supplies of resources to China, are run as businesses, and are not merely Beijing’s puppets. For the most part it is incorrect to talk about a Chinese grand strategy in the region, but Robert Hormats notes that energy-security is one area where China has made numerous decisions “based on strategic rather than market calculations, [and has shown] a preference for acquiring equity stakes in oil rather than trusting market mechanisms… because … the Chinese believe that in a crisis international oil companies might not be able to provide deliveries of Oil to China.” [22] Therefore, while the oil companies retain a measure of independence, energy security is of the utmost national importance to Beijing. Moreover as any Chinese company making tracks in Latin America is perceived as a ‘China threat’ by American hawks, it is necessary to discuss their progress.

Resource deals, current and prospective

In Ecuador in August 2003, “the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) was accorded prospecting rights by Ecuador’s President, Lucio Gutierrez. A few months later, China National Chemical (Sinochem) bought 14 percent of an oilfield in Orellana Province from ConocoPhillips for $100 million,”[23] incidents which highlight China’s long term desire for steady supplies of resources rather than quick fixes. Similarly in 2004, “the CNPC bought a subsidiary of PlusPetrol in Peru, PlusPetrol Norte, for $200 million”[24] and subsequently in 2005 “China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation (Sinopec) signed an agreement with Cuba’s Cubapetroleo to develop the field at Pinar del Rio on the west coast of the island.”[25] China signing agreements with traditional allies such as Cuba may not be overly surprising to outside observers, but it is the broader efforts to attain sources from all over the continent that are potentially more significant.

Most surprising of all is how hard China is trying with U.S allies, a fact that contradicts a lot of the conjecture that suggests China only fills vacuums the U.S leaves. In particular, “in Colombia, China is offering to finance the construction of an oil pipeline on the Pacific Coast, to move oil to the Tribugal terminal in the Chocó region from Venezuela’s Maracaibo region.” [26] The other interesting point about this development is despite the souring of Venezuela-Columbian relations, which reached its climax over controversies surrounding the alleged funding of FARC (Armed Rebel Forces of Columbia, a rebel insurgency group) by the Chavez administration in Caracas, China sees merely the economic picture, viewing Columbia as a route to the Pacific from which to transport Venezuelan oil rather than as an adversary of an ally (Venezuela), or an ally of an adversary (the United States).

Sino-Venezuelan energy relations

As mentioned above, although not exclusively, most of China’s most high profile oil deals have been with Venezuela, led by the enigmatic Hugo Chavez, a country that at least in principle, should be considered an ideological ally. Xinhua reports that Venezuela’s average daily exports of Crude oil were 55,000 in the first quarter of 2007, a year-on-year increase of 40.3%. [27] China has not just been interested in oil, but in the exploration of hitherto untapped oil fields. Lafargue notes that in August 2005 “China and Venezuela created a joint company, in order to develop the Zumano field in the state of Anzoátegui, where reserves are estimated at 400 million barrels,” [28] suggesting Beijing is in for the long haul. In the same month, Hugo Chavez announced that Venezuela intends to “increase its number of tankers from 21 to 58 over the next seven years with a ship-building program in cooperation with China,” [29] clearly signifying its commitment to increasing trade with China, despite the high freight costs of traversing the Pacific. Mainly for ideological reasons, “Venezuela has vowed to increase its oil exports to China to 1 million bpd by 2011, although energy analysts maintain that there are … difficulties with this ambition,” [30] including the current inability of China to process Venezuelan heavy crude, which will be dealt with in detail below.

It has to be mentioned though, that contrary to the belief held in America, dealings with Venezuela come at a political cost. Rather than being the architect of a malevolent anti-U.S coalition, China is in fact, a rather manipulated party. Winning suggests that Hugo Chavez has been “seeking a counterweight to Washington, which buys 12% of its crude oil – Venezuela has been courting Beijing with a promise to triple oil exports to China, including products like fuel oil, to 1 million barrels per day by 2012.” [31] Energy is China’s soft spot – it badly needs reliable supply of resources, but simultaneously, as part of its ‘peaceful rise’ it cannot afford to draw the ire of the United States. Therefore Beijing has to walk the political tightrope between appeasing Caracas’s desire to agitate Washington, and appeasing Washington’s mistrust of any Sino-Venezuelan cooperation. Llana and Ford summarise the differing motivations as follows:

While Chavez’s rhetoric revolves around the creation of a new “multipolar” world – one with multiple power centres – China is driven mostly by the need for primary products, as it devours goods from Africa to Latin America, and anywhere else it can find the raw materials it needs to fuel its rapid economic growth. [32]

Essentially, if Venezuelan hydrocarbons were not so important to the Chinese economy, Beijing would not have any involvement with the Venezuelans as it is not in its interest to draw the ire of the sole superpower.

China’s crude oil refining capabilities

A significant roadblock in this relationship is down to the fact “China does not have the capability to refine Venezuela’s heavy crude oil,” [33] which seriously limits the scope of any further deepening of Sino-Venezuelan energy linkages. The only way China can refine it is by blending it with lighter crude that it produces domestically to make a refinable hybrid. The blending process is complicated however because of the inefficiency of the refineries available to China, which will limit the amount of Venezuelan oil China can process. [34]

However, in May 2008 it was announced that the China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC) and Petroeleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) are forming a joint venture to refine Venezuelan heavy crude both in Venezuela, and in China [35]. The exact worth of this venture is still unknown though. Erikson suggests the new refineries will not help much either, because “pre-existing agreements with Saudi Arabia leave little room for processing sour Venezuelan oil in large enough quantities to displace the U.S market.” [36] This suggests to us that while Venezuelan oil is still important to China, relations with the world’s largest oil suppliers take prevalence, underlying once again that economics rather than politics is the bottom line for Beijing.

American concerns over displacement

The U.S has some reason to be concerned by the economic implications of China’s resource drive in Latin America because “while the United States has traditionally looked to Latin America as its source of numerous raw materials and a market for its finished products, China is fast replacing the United States in these roles.” [37] The United States has no intention of being usurped in its role as chief beneficiary of the regions energy resources, but “for every barrel of oil that China purchases from Latin America, there is potentially one less barrel available for the U.S” [38] It is of course extremely premature to be using words such as usurped as China’s involvement in the region is at a very early stage and its energy interests are not overly well defined, but already, “China’s total consumption of the five basic commodities – grain, meat, oil, coal and steel – has already surpassed that of the USA in all but oil,” [39] leading many analysts such as Hutton to wonder how the global supply of energy can cope with the emergence of such a hungry economy without conflict over increasingly scarce resources. [40]

The development of China and its interests in the region is therefore key. Roett & Paz argue that “what matters most… for Sino-Latin American energy relations is not where China is today but how it compares with its position in the world at the start of the twenty-first century and where it is likely to be in 2030.” [41] Due to the triangular relationship between China, the U.S, and Latin America, any shift of the equilibrium towards China cannot fail to impact upon the United States. Bajpaee moots the idea:

While not a zero-sum game, growing inter-linkages and interdependence between China and Latin America is likely to come at the cost of the United States’ relations with its neighbours, which will only undermine U.S ability to access the region’s energy resources. This will force the U.S to rely on energy resources from more remote and less stable regions, such as West Africa, the Caspian and the Middle East. [42]

However, the future of Sino-American relations with regard to energy relations is not purely China’s responsibility – America has a part to play too. Zweig suggests that “if the U.S responds negatively to Chinese efforts to secure resources or improve China’s ‘energy security’, the U.S will not be creating incentives that encourage China to behave responsibly. Energy disagreements, then, may indeed become a source of a new cold war.” [43] It must surely be in both sides best interests to avoid such a scenario.

China’s rise and U.S energy security

The U.S has more specific fears about energy being used as a weapon, in particular by the leading oil exporter in the hemisphere, Venezuela, which “has forged probably the closest relations with China of any Latin American country, and is planning to sell increasing amounts of oil to China as part of its effort to reduce dependence on the openly hostile US government.” [44] Hugo Chavez has described the U.S as imperialist in its dealings with Venezuela and the developing world. Despite this, Venezuela still supplies over 1 million barrels of oil every day to the U.S and remains its 4th largest oil supplier [45] although “Venezuela’s proportion of U.S oil imports is in decline, from 17 percent in 1997 to 11.8 percent today.” [46] Nevertheless, Chavez would dearly love to downscale this relationship, as his “ultimate goal is to provide 15-20% of China’s oil import needs. Much of that might have to come from what the United States now receives.” [47] The U.S is not dependent on Venezuelan oil to the extent it is dependent on Canadian, Saudi Arabian, or Mexican resources, but the hegemon does not like to be forced into diversification at others behest.

Another worrying trend emerged for the United States recently. The “PDVSA and Exxon are locked in a fierce legal battle over compensation for the 2007 nationalization of a jointly owned heavy oil project in Venezuela’s Orinoco basin,” [48] a dispute which has left Exxon out of pocket and several Venezuelan tankers that were heading for the U.S without a destination. Soon, the Associated Press got wind of the fact that Venezuela was now rerouting all the oil to China that had previously been on its way to the U.S refinery for Exxon Mobil Corp. [49] This is an isolated case, but it is also a microcosm of the potential future of Latin America as a whole – and certainly serves as notice that “developing Chinese interest in the region indicates that the U.S will face growing competition by other energy hungry nations and can no longer take Western Hemispheric energy for granted.” [50]

Taiwan – domestic, or foreign policy?

China’s goals in the region amount to more than the capture of natural resources. Although the People’s Republic of China considers resolution of the Taiwan issue to be a domestic issue, it is with some irony that one of China’s main foreign policy goals is to isolate Taipei internationally. The PRC and the ROC compete directly for international recognition among all the states in the world. . Nowhere is this more evident than in Latin America, where 12 of the 23 nations that still have official diplomatic relations with the ROC reside.

The historical background

Following the mainland Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War in 1949, the nationalist Kuomintang retreated to the island of Formosa (Taiwan) where it continued to claim to be the legitimate government of all of China. In June 1950 the United States intervened by placing its 7th fleet in the Taiwan straits to stop a conclusive military resolution to the civil war and slowly the battlefield became primarily political, concerned with legitimacy.

When the United Nations was formed in 1945, the Republic of China (ROC) became one of the five permanent members of the Security Council. This gave the ROC a de facto advantage over the PRC in attaining recognition from other nation states; particularly as the diplomatic clout of the hegemonic United States supported its position as the true representative of the Chinese people, until the rapprochement of the 1970s, when the Nixon administration wished to improve ties with the de facto rulers of China in order to exploit the Sino-Soviet split. UN Resolution 2758 granted the ’China seat’ to the PRC at the expense of the ROC who were in effect exiled from the organization, and the famous 1972 visit of President Nixon to China further added legitimacy to the communist regime. All this resulted in a thawing of world opinion, and gradually as the durability and permanence of the PRC regime became ingrained, countries began switching their diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing.

The economics of international recognition

In the Americas, the PRC had international recognition and longstanding support from ideological allies such as Cuba. However, the ROC has maintained more diplomatic support in the Americas than any other region, mainly due to the small nature of the states involved and the importance of Taiwanese aid to their economies. Li notes that “from the late 1980s to the early 1990s, roughly 10 percent of Taiwan’s direct foreign investment (FDI) went to Latin America and the Caribbean,” [51] highlighting the concerted effort made in the region. Economic solidarity is increasingly important to the formation of the Taiwan-Latin America relationship, for two reasons. The first is that for Latin American states, the decision of which China to support is less ideological and political than it ever has been; which makes the decision a straight up economic zero-sum choice. The second is that Latin America is home to natural resources which are of great significance to the hungry growing economies of the PRC and the ROC regardless of international recognition.

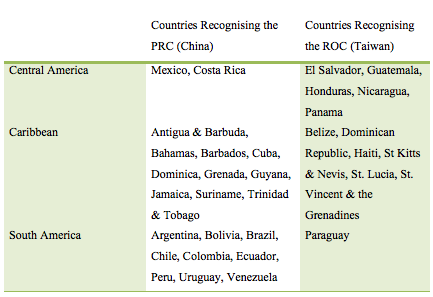

However, while the decision is not political for Latin American countries, for Taiwan, every country which switches its recognition to the PRC damages its legitimacy as a nation state in the international arena. The Table below shows the designation of diplomatic recognition in the region in 2008.

Table 2: Diplomatic Recognition of ‘China’ in Latin America [52]

Countries Recognising the PRC (China)Countries Recognising the ROC (Taiwan)Central AmericaMexico, Costa RicaEl Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, PanamaCaribbeanAntigua & Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Cuba, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, Trinidad & TobagoBelize, Dominican Republic, Haiti, St Kitts & Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent & the GrenadinesSouth AmericaArgentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Uruguay, VenezuelaParaguay

On the other hand, for the PRC, every state which withdraws its support for the ROC takes it one step closer to being in a position where it can resolve the ‘Taiwan issue’ unilaterally. Subsequently, undermining Taiwan is of the utmost importance to China, and it has taken to ‘outbidding’ Taiwan in offers of foreign aid, a strategy made possible by the decline in aid from the defunct Soviet Union, and the West, which is pre occupied with terrorism and the Middle East. Li notes that “the region’s leaders have turned to Asia for help to promote trade and financial assistance, and consequently played the PRC and Taiwan against each other.” [53] Despite its smaller size, Taiwan has fared remarkably well in this bidding war; focusing its aid investments on infrastructure such as stadiums in St Kitts & Nevis for the Cricket World Cup in 2007.

However, even Taiwan‘s economy can be put under strain by the seemingly relentless stream of foreign aid which has brought only debateable and mild gains to the Taiwanese cause. This has contributed to the PRC picking off the few remaining supporters of the ROC – take for example, the Dominican case.

In early 2004, Commonwealth of Dominica asked Taipei for a $58 million aid, which is unrelated to public welfare. The Caribbean nation had relied on Taiwan to develop its agriculture-based economy since 1983. Diplomatic relationship was soon broken after Taipei turned down the request. [54]

This incident showcased the fact that in economic terms, the PRC is winning the battle for Latin America.

Political strategies of the PRC

In political terms too; the PRC is in an advantageous position, thanks in part again to its position within the UN. While it can be argued that China “provides incentives but does not threaten harm to induce countries to defect from recognizing Taiwan,” [55] the reality is that the use of force and direct harm are not the only means available to an economic entity as powerful as China. It refuses to maintain official relations with any state that recognises the ROC; an action which can be quite prohibitive to the country being able to take advantage of the growing Chinese market. Although Domínguez suggests that the PRC “has not been punitive toward those states that still recognize the Republic of China (Taiwan),” [56] the legitimacy of this claim has to be brought into question – for example “in June 1996, China fought the extension of the UN mission in Haiti, to punish the Caribbean nation for its appeal for UN acceptance of Taiwan.” [57] This incident showed that China is prepared to use its global clout to play spoiler and apply indirect pressure on countries to adopt its position. Similarly, China’s experience with one-party rule has taught it the importance of party-to-party relations in addition to state-to-state relations, further cementing the PRC by establishing a relationship based on goodwill and common understanding. Indeed by the start of 1998 “the CCP had established relations with almost all major political parties in the countries that were Taiwan’s diplomatic allies in Latin America,” [58] further isolating the ROC.

The effect on American interests

Were the ROC to be deserted by its remaining allies in Latin America, the USA would be disadvantaged in attempting to maintain the status quo across the Taiwan Strait. A Taiwan that was not recognised by any state from the Americas, or Europe (with the exception of the Vatican) would not be seen as a genuine sovereign entity whose defence would be more important than the upkeep of good relations between China and the West. As China’s economic and political position in the world improves vis-à-vis both America and Taiwan, so might its ambitions. The U.S.A might find itself in a position where it could no longer withstand the diplomatic pressure to allow the PRC to conclude a settlement on Taiwan, perhaps by force.

Having illustrated China’s goals in the region, the next chapter will examine how these goals are manifesting themselves in the way of political and economic deals and linkages.

CHAPTER THREE: Political & Economic linkages between China and Latin America

As shown in the previous chapter, China greatly desires the natural resources which Latin America is so rich in. To facilitate this it has advanced greater political, economic, and cultural ties to the region in an effort to position itself as a preferred trade partner for many of the countries whose resources it seeks. In this chapter we will examine this burgeoning relationship and ask whether it has any consequences for the United States.

Latin America’s attractiveness as a market

Latin America does not serve only as an attractive reservoir of potential resources, “with a population of over 500 million and an economy of nearly $3 trillion, [it] is an attractive market for Chinese products.” [59] Greater economic linkages are almost certain to lead to greater political cooperation too, as economics and politics are inseparable.

Complimenting economies

Another important point is that China and Latin America are very suited trading partners, not only just now, but in the future. Devlin et al note that:

In the past two decades, bilateral trade linkages between China and Latin America have increased. Efforts to forge closer economic ties to benefit from accelerating Chinese demand have already borne fruit, with some Latin American countries becoming important suppliers. Although most of these exports are raw materials and commodities, China could start absorbing higher-value-added products as per capita incomes and consumption rise. Demand for more sophisticated and more-varied products is also likely to grow, increasing the possibilities for intra-industry commerce in bilateral trade. [60]

The key point here for Latin American countries is while today China is interested only in primary products, as it gets wealthier and the size of its middle class grows, so does its demand for more value-added products. This makes China a very appealing prospect due to the potential long term trading relationship that could arise.

However, this trading partnership will only flourish if significant effort is put into making sure China and its Latin American trading partners remain compatible. Speaking at the Brazilian parliament during a state visit, Hu Jintao emphasised the need for;

Complementing each other economically and building mutually beneficial and win-win partnerships at new starting points. Both sides should take active actions to try to raise bilateral trade volume to more than US$100 billion in 2010, doubling the current level and at the same time make great progress in the field of investment, with the total investment volume doubling and both sides becoming the partners of each other of greater importance. [61]

He added that the two sides should make optimizing trade and developing cooperation in high-tech sectors and industries with high added value a priority. [62]

FDI

As part of its opening up to the world, Beijing has been eager to create a climate where China holds a greater stake in the future of the world economy, a sharp contrast to its days of self reliance and import substitution. Devlin et al note that “although China’s stock of outward FDI is small, US$33 billion in 2003, attracting Chinese FDI is more likely now that Chinese industrial policy encourages its industrial giants to become global players and also targets secure supplies of strategic raw material imports.” [63] This has been heeded by the private sector, and Li notes that as of 2005 “about 200 Chinese enterprises have invested some $1 billion in twenty Latin American countries.” [64] Latin America is a region that is primed to benefit from this as China has great interest in being on hand to absorb resource exports. Recent figures show that “the cumulative stock of Chinese FDI in Latin American and Caribbean rose from $4.6 billion in 2003, accounting for almost 14% of China’s FDI stock worldwide, to $11.5 billion in 2005, accounting for 20% of China’s investment worldwide,” [65] suggesting that as Chinese political interest in the region has grown, so too has its investment.

Trade

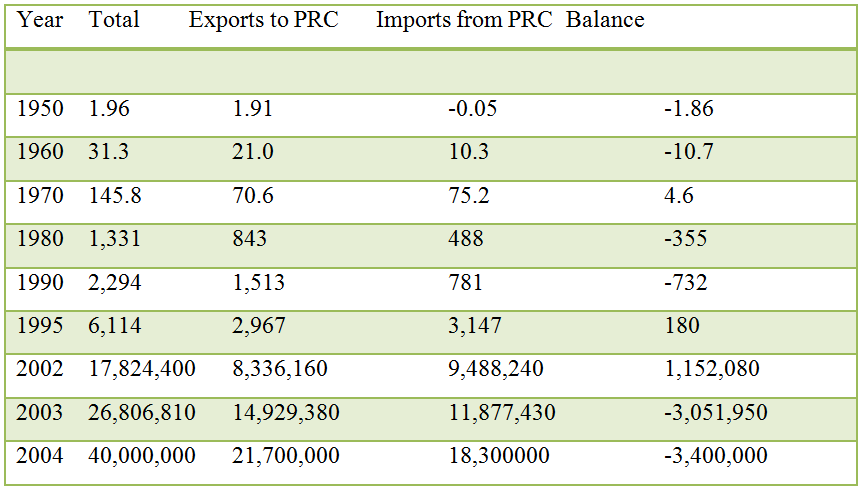

Chinese trade in the region has grown significantly. The table below shows the astronomical rise in Latin American trade with China.

Table 3: Latin American trade with China (figures in US $million)[66]

The pace of this growth is incredible, and is undoubtedly fuelled by China’s desire for resources. Lafargue suggests that “in conducting its campaign of economic and political expansion, China has adopted the following modus operandi: It negotiates and ensures regular oil supplies in exchange for investment; it then uses commercial ties to generate agreements on political and military cooperation.” [67] The importance of politics as a stimulus for economic cooperation, as well as an end result of it, has not been lost on China. Zweig and Jianhai highlight the importance given to the intertwining of politics and economics by top Chinese and Latin American officials, going as far to call China “the main impetus for export growth in many Latin American states.” [68]

Although at this point “China has not made a political decision to prefer trade with Latin American countries at the expense of its trade with other countries,” [69] China’s overall economic and trade growth has meant that it simply does not have to choose trade with one region or nation at the expense of another. A more accurate depiction of the growing importance to China of Latin America would be the speed of growth of its trade. Dreyer reports that “from 2001 to 2003, the average annual growth rate of China’s trade with Latin America was 25.4 percent, compared to 22.1 percent globally, and this trend accelerated in 2004 and 2005.” [70] While growth in trade with Latin America is only slightly above its global growth average, it does give a brief glimpse of the potential importance of Latin America. Much like every other aspect of this study, the question isn’t so much how important is Latin America to China now, but how important Latin America could be.

The Chinese economic threat to the U.S in the region

The U.S is still the most important economic partner for Latin America, but recently many in the region have felt neglected by Washington, whose focus on terrorism and the middle east and ‘rigid U.S. foreign policy toward Latin America has left regional leaders with no option but to look for other patrons. Net foreign direct investment in Latin America has fallen from $78 billion in 2000 to $36 billion in 2003.” [71] This economic neglect is exacerbating the political grievances of the likes of Hugo Chavez, but the more moderate social democratic governments of Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, recently extended the designation of Market Economy Status (MES) to China, something the U.S and the E.U have still denied. MES “substantially diminishes the effect of anti-dumping legislation under World Trade Organization rules. Given the preponderance of non-market factors in the P.R.C.’s economy… there can be little doubt that the three countries made their decision almost exclusively on the basis of China’s growing political and economic influence.” [72] This highlights the politico-economic independence of the U.S that Latin America is exerting.

This is also symptomatic of a deep paradox in the American thinking about how to deal with China. On one hand, tying the nominally communist state to the world economy is expected to bring about economic maturity and gradual political change, but on the other, China is still a U.S rival whose influence China is competing against. The situation is reciprocal, as China views the U.S as “[using] its economic leverage to exert political pressure on China, which is one reason that China seeks to diversify its economic relationships.” [73] In this respect, the U.S has what it wants – China is intrinsically tied to the ideals of the open market – as a lower cost, less politicized alternative to the United States.

The prevailing economic dominance of the United States

However, it is both premature and alarmist to equate China’s growth with a usurping of the United States as regional hegemon. U.S trade and investment continues to make China look miniscule by comparison:

China’s overall trade with LAC grew to about $70 billion in 2006, representing just 4% of its overall trade. In comparison, U.S trade with Latin America and the Caribbean amounted to almost $555 billion in 2006, accounting for about 19% of U.S. trade worldwide. [74]

Not only is U.S trade larger in real terms, but the fact it accounts for a much larger percentage of overall trade shows the relevant importance of Latin America to China and the United States. The picture is the same for the Latin Americans, for whom the United States is still the preferred trading partner.

In 2006, almost 38% of the region’s exports were destined for the United States, compared to 3.7% destined for China; likewise, over 34% of the region’s imports were from the United States in 2006, compared to almost 8% from China. While China’s reported cumulative stock of FDI in the region amounted to $11.5 billion in 2005, the cumulative stock of U.S FDI in the region amounted to $366 billion in 2005, and grew to $403 billion by 2006. [75]

Globalization may have opened the world up, but geography hasn’t disappeared completely. For one, high shipping costs mean that “while China’s economic linkages with Latin America have grown, the U.S advantage of geographical proximity means that the PRC presence is likely to remain dwarfed by U.S trade with and investment in the region,“ [76] China is a growing power, with rapidly expanding resource needs – but it is also predominantly an East Asian nation.

A final point is that although Sino-Latin American economic relations are advancing, they are not without hiccups. The granting of Market Economy Status to China has caused some Latin American economies problems, particularly Brazil who have found their market flooded with cheap Chinese imports. Also, while Latin America is attractive as a market to China, it does not offer the same potential return as the U.S market does for both parties. Although the Export similarity index [77] notes that only Mexico (and to a lesser extent Brazil) are directly competing with China, as the economies of Latin America develop they may find themselves squeezed out in a battle with China for access to the U.S market as they cannot compete with China’s low cost products.

China’s rise in a global context

Politically too, China is making advances in Latin America, abiding strictly by the main tenets of its ‘peaceful rise’ strategy. Beijing says that although it does not seek hegemony, it “advocates a new international political and economic order… that can be achieved through the democratization of international relations.” [78]China does not intend to rock the boat, but of course, the concept of a new international and political order comes at expense of the old order. Foot suggests that “while Beijing’s strategy can be viewed as accommodation with the current US-dominated global order, it also contains an important ‘hedging’ element, or insurance policy, through which China seeks to secure its future.” [79] This means that the strong bonds China creates with countries all around the world are vital to ensure that China can oppose the U.S. on individual issues from a sure footing without encountering the wrath of the entire global community, and in effect allows China some breathing room from which to operate politically without incurring the wrath of the U.S..

China has many carrots to dangle in its pursuit of international influence, such as access to the world’s largest emerging market. A Congress report portrayed China as “trying to project soft power by portraying its own system as an alternative model for economic development, one based on authoritarian governance and elite rule without the restrictions and demands that come with political liberalization,” [80] but the inference that China has any interest in the internal economic workings of its trading partners is ignorant of the depth of the peaceful rise, China’s non interference policy and its new found ambivalence towards ideology as a source of kinship. A truer characterisation is that China has “attempted to exploit its ‘‘no strings attached’’ foreign aid stance and its ability to deploy state-owned assets to reap soft power advantages,“ [81] but even this ignores the fact that every nation-state attempts to reap soft power advantages, it is intrinsic to the nature of international politics.

Political and cultural elements in China’s burgeoning relationship with Latin America

China has also emerged as a favoured political partner for Latin American countries, mostly because (as mentioned above) it has a no-strings approach to doing business. Its “‘holistic approach’… has become an attractive alternative to traditional Western companies, which do not have a similar integrated package of carrots to offer… a Chinese deal literally can mean an ‘alternative economic lifeline’,” [82] because it offers a less bureaucratic alternative to American aid and political assistance.

As both China and Latin America are part of the developing world, some argue that they “share several broad interests in the multilateral trading system and collaboration there can spill over into improved bilateral relations.” [83] Political alliances are not built solely around either class or power, but interest. However, in a 2006 study, it was shown that “the jump in Sino-Latin American trade has had little impact on agreement between China and any of these six Latin American countries (Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, Panama & Paraguay) in their voting behaviour in the U.N. General Assembly.” [84] The argument could be made that these findings merely show that as of yet China has not been successful in its attempts to manipulate political ends through economic means, but the reality is that Latin American countries, like China, are not so much ideological and more pragmatic in their international outlook.

On the subject of International organizations though, in 2004 China was granted permanent observer status to the OAS (Organization of American States), an opportunity which “will provide a new platform for the exchanges and cooperation between China and American states.” [85] The importance of open dialogue is becoming apparent to China as it begins to look outwards even though the Chinese are not fluent in their understanding of Latin Americans business practices yet. [86] The language barrier can also hinder the smooth completion of trade. To counter this, China has been setting up Confucius institutes all over Latin America in an attempt to further cultural exchanges, and with Beijing’s support, Chinese language classes have become very popular. However, this has not been an easy transition. As the United States is still the largest trader on the continent, “English prevails as a second language,“ [87] but these cultural impediments and China’s attempts to combat them are further evidence of China’s growing understanding of the nuances of international politics and the value of soft power. China has dedicated some regions as official tourist destinations for Chinese citizens, giving a welcome boost to their economies, [88] and increased the number of high ranking state official visits to the continent. Li Jianmin describes one of the initiatives the PRC has undertaken to further improve China’s image in the Western Hemisphere:

China and Latin American countries have forged 57 couples of “friend cities” or “sister cities,” according to Li Xiaolin, vice president of the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries. The relations between China and Latin America are described as “the best ever in history. [89]

This is not a new form of political flattery, even for China, but it does demonstrate the growing political importance of Latin America in Beijing’s scholarly thinking.

Why does Chinese political advance in Latin America affect the United States?

The no strings approach that appeals so much to Latin American countries is precisely what worries and antagonises the West, which views China as undermining attempts to promote democracy and transparency and human rights in the region. [90] The U.S in particular fumes as China “strikes deals with states they have tried to marginalize,” [91] referring of course to Cuba, and Venezuela – the former of whom could not have survived a U.S embargo for so long without Chinese and Venezuelan support. Harry Harding suggests the possibility that “the Chinese government will be more supportive of the host governments of the countries in which it has key investments or contracts, regardless of those governments’ international orientations or domestic human rights records.” [92] China must realise that while it intends its actions to be benign and its attitude to be ambivalent, the U.S may choose to interpret its ambivalence towards certain regimes as closer to toleration.

Political analyst Mary O’Grady suggests that “the idea that China offers an alternative to dealing with the U.S in both economic and political terms… is likely to appeal to the likes of Hugo Chavez, Brazil’s President Luis Inácio “Lula” da Silva and Argentina’s Nestor Kirchner.” [93] Some view this as amounting to the emergence of a “’Beijing Consensus’ that offers an alternative to the market economics and limited state intervention that was set forth by the “Washington Consensus” in the early 1990s.” [94] This fear that it could be displaced as hegemon by China emerges because it has no desire to see Latin America slip from under its control, but also because the long term American effort to politically isolate the PRC could become much harder to execute. The worry is that “China could try to use its newly formed bilateral and multilateral relationships to offset any serious deterioration in relations with America” [95] and become less dependent on bilateral political relations with the United States in an attempt to become more independent. Hurrell states:

China has sought to accommodate itself to US power and to seek coincidences of interest. It has criticized but acquiesced in US policies with which it has fundamentally disagreed—Iraq most notably—and has been less strident than Brazil and India in opposing US preferences within the WTO. But this has been counterbalanced by a broadening range of stances designed both to retain flexibility if relations with Washington should deteriorate and to lay the groundwork for a more active foreign policy in the future. [96]

A more active Chinese foreign policy is precisely what the U.S hopes to avoid. Presently, despite its rise, China punches well below its weight in matters outside of East Asia. A more politically active China would be seen as a direct competitor to Washington; even if its intentions were benign.

The next chapter examines the possibility that a military threat might arise from the framework of these political and economic linkages, and discusses the implication for America.

CHAPTER FOUR: Military threats & the Panama Canal

This chapter seeks to identify and analyse the actual and potential Chinese military involvement in Latin America, and the likely U.S reaction. There is also the particular case of the Panama Canal, a so called geopolitical ‘chokepoint’ which brings a unique set of challenges and opportunities to China and to the U.S., which we will examine here.

China’s emergence as a military power

We have detailed China’s growing challenge to US dominance in Latin America, dealing for the most part in economic terms, but “some believe that China’s economic challenge inevitably gives rise to a simultaneous military threat.” [97] Denny Roy suggests that:

If China fulfils its expected potential, it will soon be a power in the class of 19th century Britain, the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, Pacific War Japan, and 20th century America. Each of those countries used its superior power to establish some form of hegemony to protect and promote its interests. There is no convincing reason to think China as a great power will depart from this pattern. [98]

This is a central tenet of the China threat, that a rising power will seek – to borrow a phrase – its ‘place in the sun’ at the expense of global stability. The history of the world suggests that “prosperity and advancement will naturally strengthen China’s military power – something that worries the United States.” [99]

The U.S is worried because in our current unipolarity, global stability is intrinsically linked to the permanence of the hegemon. The Director of the Asian Studies Centre at the Heritage Foundation, Peter Brookes, has been quoted as saying that “China’s grand strategy was to gather as many friends and allies as possible to counter U.S dominance in the region” [100] in an attempt to “balance against US power.” [101] The idea that China is trying to create an anti-U.S coalition is a frequently cited one, as many pundits think that China’s aim is “undermining the United States around the world and raising China to a position of dominant international political and military power.” [102] This point of view is held by a vocal minority who choose to interpret Chinese actions as designed against the United States.

Military build up and U.S concerns

The U.S is concerned with the potential for China to attain a forward base from which to disrupt key U.S interests. The Commander of the Southern Command General Bantz J. Craddock told a hearing of the House Armed Service Committee that:

The PRC’s growing dependence on the global economy and the necessity of protecting access to food, energy, raw materials and export markets has forced a shift in their military strategy. The PRC’s 2004 Defence Strategy White Paper departs from the past and promotes a power-projection military, capable of securing strategic shipping lanes and protecting its growing economic interests abroad. [103]

The key idea here is that China might begin to exert itself and the U.S may find that it is not the only player in the Latin American equation. To give you an idea of how alien and disturbing a concept this is to the U.S, the Western hemisphere is not even considered a part of the ‘game board’ in grand strategy analyst Zbigniew Brzezinski’s ‘The Grand Chessboard’ [104].

Yet the possibility that it could become a contested area is increasing, with China taking a greater indirect role in the region. Hearn warns that:

China appears to be pushing to sell arms and technology to Latin America, especially to Venezuela, a key ideological partner that is working to reduce dependence on the U.S as a primary weapons supplier. China recently offered to sell Venezuela its new FC-1 fighter, a potential follow-up on its failed bid in 2001 to sell Caracas its low-tech K-8 training aircraft, one U.S.-based intelligence source says. Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez signed deals to purchase long-range defence radars and a modern communication satellite from China. [105]

This is a recurring theme for some analysts, who portray Chinese involvement in Latin America as purely on an ‘arms for oil’ basis [106], but there remains significant worry about the perceived Sino-Venezuelan-Cuban axis, and how it will develop as China seeks to protect its investments. One potential justification would be the protection of overseas Chinese. Lafargue notes that “in Venezuela, several Chinese expatriates have recently been killed. Such actions could enable Beijing to justify a more assertive military presence.” [107] This military presence would be perceived as directly threatening to the United States, not least because combined with the PRC’s “human and commercial infrastructure in Latin America… [China] would be well placed to disrupt and distract the United States in the hemisphere and to collect intelligence data against U.S forces operating in the region” [108] in the event of any possible U.S military conflict with China.

Espionage is not the only U.S. strategic worry, many analysts fret that a Chinese led anti American alliance could “potentially isolate and undermine the U.S economy… and seek to engage in a form of asymmetric warfare against the United States by cutting off vital oil supplies,” [109] further evidence of why the U.S. is so concerned by forward Chinese progress in securing Latin American resources. Nor is the fact China’s armed forces will not attain serious power projection capabilities any time soon a comfort to the U.S. We go back to the ‘China threat’ idea of potential capability rather than intentions. Denny Roy surmises that “the point is not what China can deploy now, but in a decade or two, with a much advanced economic and technological base.” [110] Still, there are issues even in 2008 that the United States considers worrying.

Haiti and China

Nothing highlights the growing presence of China better than the Haiti case of 2004. Following a request for help from the Haitian government and a UN resolution, China sent a “’special police’ peacekeeping contingent of 125 personnel as part of the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) that began in 2004.” [111] Although the mission is Brazilian led, from the point of view of this essay this is a very significant occurrence as these are the “first Chinese troops to be deployed to the Western Hemisphere,” [112] albeit in a very minor capacity. It also highlights the fact that the U.S has not paid as much attention to the region as it perhaps should have, with a larger focus on the Middle East blinding Washington to its own back yard. However, despite the continued presence of these Chinese peacekeepers Haiti has not switched its diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the PRC, perhaps illustrating that China’s current strategies to achieve its political goals have a long way to go yet.

Sino-Cuban political and military cooperation

A more traditional worry of the U.S has been Cuba. The PRC has maintained good relations with Havana throughout its entire existence, but it wasn’t until Castro’s disaffection with Moscow led to a weakening of Russo-Cuban relations that China took over the mantle as chief protectorate of the island. Ideology (at least for China) is not the factor it was in this relationship, but the island nation still retains value both politically and economically to Beijing because of its raw materials, a fact highlighted by the high profile visits by Hu Jintao at the start of the century. Cuba also lets China use abandoned Soviet telecommunications infrastructure on the island [113] which has great potential espionage value given its proximity to the United States.

The United States has imposed a longstanding embargo against Cuba, so any efforts to economically strangle the island are naturally offset by aid from Beijing (and Caracas). There is a fear that a growing China might be more and more willing to protect its Latin American and Caribbean interests by force as its power projection grows. Erikson notes that “as China’s political and economic clout continues to grow, Cuba is poised to become Beijing’s most valued beachhead in the Caribbean.” [114] While not a direct threat in its own right, Cuba has existed as a troubling client state for America to deal with. Hopes that following the end of Fidel Castro’s reign Cuba may be coaxed or forced back into the global communiqué of nations (and therefore the U.S’s sphere of influence) seem futile while China is in effect helping to sustain the economic system of the island through aid, and generous trade terms. Erikson laments that “U.S. policymakers who dream of re-making Cuba should be aware that China and Venezuela are poised to loom ever larger in Washington’s rear-view mirror.” [115] This situation in many ways could end up mirroring the Taiwan Strait, where one great power postures in such a malignant way that the status quo is maintained as an alternative to the prospect of outright conflict.

Portraying Sino-U.S military relations

The problem with Sino-Latin American military relations is that they are distorted by perception and portrayal. A more apt assessment would focus less on the formation of anti-American alliances and accept that “military relations are not the cause that propels Sino-Latin American relations; rather, they are one effect of those relations.” [116] R.E. Ellis suggests that there doesn’t even need to be evidence of a China threat or military build up – the mere presence of China at all in the region is fundamentally unacceptable to the U.S. [117] But agitating China and treating it as a threat may ironically be the biggest military threat to the U.S from the region. A strong argument can be made that “counsel to treat China as a major threat to U.S interests is designed to justify huge U.S military budgets and is more likely to bring about conflict with China than to deter it” [118] and that fear of China as a military threat, and treating it as a military threat, may become a self fulfilling prophecy. Whether the United States is willing to accommodate Chinese interests in the region is another question altogether.

The Panama Canal

Following worsening relations between the United States and Panama, the Torrijos-Carter Treaties, signed in 1977, ensured that the Panama Canal was transferred from U.S to Panamanian control. The U.S, who had originally built the Canal which opened in 1914, retained a right to defend the canal’s neutrality using force should such a circumstance ever arise. The canal was formally transferred to Panamanian hands on December 31st, 1999.

However, U.S paranoia was piqued by the acquisition of two ports, one on each side of the Panama Canal by Hutchinson Whampoa; a Hong Kong based shipping company. The ports Cristóbal and Balboa were leased for a period of 50 years starting from 1997 after a bidding process that has subsequently been considered extremely corrupted. Rumours suggest that although submitting lower bids, the Hong Kong conglomerate may have influenced the outcome by way of under-the-table payments to corrupt Panamanian authorities. Although Hutchison Whampoa is neither state owned, or even a mainland Chinese company, its owner Li Ka-shing has perceived links to the PRC and the PLA (People Liberation Army) in particular – the right wing interest group ‘Eagle forum’ calls him a “political buddy of the late Deng Xiaoping.” [119] This was enough to raise the ire of former Republican Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott, who remarked that “it is the perception of some of my colleagues and I [sic] that the Chinese involvement in Panama may not be straightforward and could, in fact, be a threat to our national security.” [120]

Although this train of thought equates Hutchison Whampoa with Beijing and incorrectly presumes China as a unitary actor, China does have goals in the region. Increased trade flow to Latin America and the Caribbean has seen the volume of Chinese ships and goods increase as China has become second largest user of the canal and the Panama Canal is fast becoming a limiting factor. For example, Lafargue notes that “the volume of Venezuela’s exports to China remains limited for the moment because of the narrowness of the Panama Canal, which cannot accept large ships,” [121] many of which China uses for the transport of oil. China has a vested interest in the ‘Third Set Of Locks’ project that is due to be completed in 2014, which will see the Panama Canal open up a new lane suitable for larger vessels. This expansion is driven by projections of Sino-US trade, further evidence of the growing importance of China in the region.

Why does Chinese involvement with the Canal affect America?

Like everything to do with the Chinese expansion into Latin America, its interest in the Panama Canal is a matter of perspective and interpretation. Some tend to attribute Chinese involvement to a greater strategy – and quite often presume to understand the intricacies of that strategy themselves. The somewhat alarmist Bill Gertz thinks that:

Geopolitically, China sees its location in Panama as a place where it can establish a base of influence in a small country, using political and commercial means, where it can work closely with its new ally Cuba to help those who oppose the United States in Latin America and where it might also be able to position weapons such as medium-range missiles that potentially could be used to threaten the United States in times of crisis, or times of the choosing of the Chinese regime. [122]

The logical leaps are crude in this scenario, but they are easily understood which makes them an easy sell politically. A report entitled “Panama: People’s Republic of China Interests and Activities” dated the 26th of October 1999 tries to link Hutchison Whampoa with espionage and terrorism using merely conjecture and speculation, It thinks that “Hutchinson’s containerized shipping facilities in the Panama Canal, as well as the Bahamas, could provide a conduit for illegal shipments of technology or prohibited items from the West to the PRC, or facilitate the movement of arms and other prohibited items into the Americas.” [123] This highlights the American tendency to deal with possibilities and pessimistic scenarios as a defence mechanism.

Immigration, narcotics, terrorism, espionage, arms, are all solid terms that can be wielded by the security-obsessed nationalist right to emphasise mistrust, and further exacerbate the perceived reality of the China threat. In his 2004 study entitled ‘The declining strategic relevance of the Panama Canal‘, Schandlbauer [124] states that all the above arguments pertaining to a threat are based on theory and possibilities because US realists care little what Hutchison Whampoa do, but what they could do. Because of this, his conclusion that the Panama Canal is now overrated as an asset to US national security is more or less irrelevant when sat next to the vitriol that accompanies matters that are attributed national security status. The ironic conclusion we have to come to is that it seems the majority of the Sino-American security dilemma originates from paranoia on the American side.

In the following section we will try and draw overall conclusions about Chinese involvement in Latin America from our discussions here on China’s goals, activities, and potential military capacity.

CHAPTER FIVE: Conclusion

Does China threaten U.S vital interests?

When answering whether China threatens vital U.S interests through its involvement in Latin America, it would be irresponsible not to give a balanced answer. We have looked at the importance of a perceived ‘China threat’ throughout the course of this study in relation to Chinese goals, actions, and capabilities. Most importantly, we have dealt with why these issues matter, or are perceived to matter to the United States, and we will conclude with some conciliatory analysis.

Re-evaluating the China Threat theory

The China threat theory, as already mentioned, is dangerous in itself for its portrayal of China as a problem. Rather than viewing China as a nation with malign intent, it is perhaps better to understand the problem as inherently “’structural’, as China is on the rise and the US wants to maintain its unipolar dominance” [125] – this means that while disagreement and conflict are still possible, both sides should recognise the other is acting out of the self-interest that is required to sustain the system as a whole.

The reality is, self-interest is a key feature of international politics, but it can manifest itself in a host of ways, not all of them Machiavellian. Better cultural and political understanding between China and the U.S would ease some of the tension that underpins the ‘China threat’ theory and pins down China as America’s ‘other’. Despite all the attention paid to China’s rise and the consequences that follow, “the United States still has a very imperfect understanding of China’s power and motivations,” [126] an ignorance which fuels the tension as much as any Chinese action. It is inevitable that there will be clashes of interests and ideals; but if they were dealt with pragmatically rather than prematurely, it could ease the Sino-U.S relationship. Emma Broomfield notes that if managed correctly, through a policy of engagement, the two powers will likely co-exist in peace and work together in the twenty-first century. [127] Greater engagement between the sides can only result in greater understanding over future issues.

Resources as a focus of cooperation

Although China is thirsty for resources, it is aware that they do not always come without political cost. Unrest in the Western hemisphere does not help China – “such a scenario, or rocky bilateral relations with Washington, might threaten energy and other deliveries to China and thus impede the country’s domestic growth.” [128] Keeping under the radar is one of the main tenets of the ‘peaceful rise’ theory and China has no interest at all in confrontation. Consider the Venezuela-Exxon crisis mentioned earlier, where tankers of oil destined for the United States ended up being rerouted to China. David Winning suggests this is because “China values its relations with Washington and will likely be loath to create new friction by being seen to benefit from the Venezuela-Exxon legal spat at a time when it is already coming under pressure for its oil investments in Sudan and Iran.” [129] This highlights China’s caution when it comes to invoking the ire of the United States. J.D Pollack thinks that not only should China and the U.S avoid irritating one another, but they actually have scope for cooperation on energy matters, such as preventing any disruption in supply, or encouraging enhanced energy exploration. [130] Even if such collaboration were improbable, for the short and medium term, Wan Jisi suggests the simple mantra that “each country should be sensitive to the others energy needs and security interests worldwide.“ [131] When an issue is treated as being within the realm of ‘exceptional’ politics, it is elevated in importance and dealt with as a security issue unnecessarily.

American support for Taiwan

The issue of Taiwanese relations with America is too complex for us to deal with here, but clearly as China grows stronger and its ties with Latin America grow deeper, Washington is going to have to decide whether its relations with Taipei are more important than a Sino-Latin American consensus on the resolution of Taiwan’s future. It’s also clear that from China‘s perspective, “a cordial relationship with Washington could isolate Taiwan politically.” [132] Whether the status quo across the strait can be maintained through Washington’s tacit support of Taiwan as Chinese power and influence increases vis-à-vis America is an issue that may increase in pressure for American policy makers.

Economic opportunities, not threats

The supposed economic threat is a matter of perception. Some of the headline figures used to highlight China’s massive growth have also been proven to be massively over-exaggerated. An Economist report in 2006 detailing the likely economic breakdown of the world in 2026 found that while China’s share of the worlds GDP at purchasing-power-parity exchange rates will usurp the U.S by 21.8% to 21.1%, the more widely used system of share of GDP at market exchange rates shows the U.S enjoying a comfortable 27.3% to 13.7% advantage. [133]

Also, considering China offers a whole new export market for the United States to exploit, “from an economic perspective, describing China’s economic rise or its economic policies as an economic “threat” to the United States fails to reflect that China’s growth poses both challenges and opportunities for the United States.” [134] Moreover, in Latin America, because it has no desire to directly challenge the United States, “China typically picks up secondary deals or moves into markets from which the United States is absent: thus in many places the two countries are not really in direct competition.” [135] This situation is likely to remain the case until if and when China feels more confident about directly challenging the U.S on political matters.

Shared political interests

When it comes to politics, the U.S and China have many shared interests, not least terrorism, and global stability. The U.S’s best interests “would be served, then, by encouraging China’s further integration into the global system.” [136] With its growing clout, China is becoming a stakeholder in the stability of the Western Hemisphere – therefore a re-evaluation of events such as the deploying of Chinese peacekeepers in Haiti should be necessary, as the U.S could come to view Chinese cooperation as beneficial in the region, and could improve Sino-American relations overall. Garrett and Adams suggest closer Sino-U.S coordination could come about “with regard to minimizing the threats emanating from failing states.” [137] Terrorism and instability in its rural areas, on its borders, and in its neighbourhood affect China massively, and like the U.S, it could soon find itself in a position where it feels obliged to defend its international interests abroad too. Latin American stability – for example in the recent Columbian-Venezuelan crisis – could become a focal point for U.S.-China cooperation.

Avoiding the military security complex

The United States must realise that it is partly responsible for any military tension with China by backing it into a corner through its relations with Taiwan, India, and Japan. Mahbubani suggests that “given how vulnerable Chinese leaders feel in the face of U.S pressure, it is only natural for them to look for ways to counterbalance U.S power.” [138] Subsequently a redressing of the security imbalance should be looked at if the United States desires to see an improvement in bilateral relations with China on this front. The likelihood however of an anti-American military alliance forming in Latin America is exceedingly slim, because ideology does not play a role in China’s thinking. Furthermore as previously mentioned, China does not desire conflict with the U.S, directly or indirectly, and certainly “will not allow Chavez to make China his ally in battles with Washington.” [139] Therefore, the United States must realise that China has no intention of drawing America’s ire in the same way Caracas and Havana have.

What should the US do?

We will conclude with some more general points about the American response to Chinese involvement in Latin America. The first is that if the U.S is so concerned about retaining its position of regional hegemon in Latin America, it must respond better to the regions needs. This includes dropping its agricultural and steel subsidies that Latin Americans find so unfair. Another would perhaps be resurrecting the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) to try and encompass all the Latin American nations firmly in the American sphere.