To What Extent Does Collier and Hoeffler’s Economic Opportunity Model Explain the Onset of the Angolan Civil War?

Introduction

The debate about whether natural resources play a significant role in civil wars has taken center stage in peace and conflict studies. From competition over fresh water to clashes over precious minerals, scholars have argued that natural resources have not only triggered violent conflicts but also financed civil wars around the world.[1] Collier and Hoeffler (2004) mount a strong case in favor of economic explanations for civil war arguing that the “economic viability” is what greatly determines a civil war. In the context of post-colonial Africa and the Cold War, there are many different factors to be examined regarding the onset of civil war. While economists like Collier and Hoeffler propose models based on economic opportunity, many political scientists prefer a model based more on grievances.

In this paper, using qualitative and quantitative data, we assess the validity of the Collier and Hoeffler model in the case of the Angolan civil war in 1975, trying to find a strong causal correlation between civil war and economic motivations. The benefit of utilizing a case study of this nature allows one to more carefully apply the vast research done by Collier and Hoeffler. Each conflict researched by Collier and Hoeffler certainly has similarities, but each conflict is unique and should be examined on its own. The econometric model covers a wide variety of potential causal factors; however, we argue it potentially gives too little weight to the impact of ethnic and racial grievances. Based on our findings, we conclude that Collier and Hoeffler’s model does not sufficiently explain the onset of the Angolan Civil War. The following brief background identifies key actors and their ideological differences. We then move to analyze Collier and Hoeffler’s econometric model. Finally, we assess their observable implications in the context of the onset of Angolan civil war.

I. Historical Background

The Angolan civil war that began in 1975 has its roots in the fight for independence from Portugal starting in 1961. During that struggle for independence, three main insurgent groups formed. [2] These three groups were the National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA), the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA).[3] After Independence, the FNLA played little to no role, and the subsequent civil war was primarily driven by sharp ideological differences between the two key actors – the MPLA and UNITA.[4] The Angolan civil war lasted for nearly three decades resulting in the death of 1.5 million Angolans and leaving over 4 million internally displaced.[5]

When the civil war initially started, the MPLA, with the help of Cuban troops and Soviet arms, repelled UNITA/FNLA forces, accompanied by South African troops, to take control of the capital Luanda on November 11, 1975. The fact that the MPLA controlled the capitol when the Portuguese colonial government left made them the de facto rulers of Angola. In the ensuing battles, UNITA was decimated and rebel leader Jonas Savimbi spent the following moths traveling through the southeast of Angola rebuilding his army.[6] Following their initial defeats, UNITA, with South African covert assistance and funds from the United States (funneled through Zaire) moved to start attacking MPLA positions and supporters.[7]

What started as a war based on differing political ideologies and personal disagreements among elites soon flared into a proxy war between the United States and the U.S.S.R. After the end of the Cold War, the focus for rebels shifted from political power to seizing and maintaining Angola’s valuable natural resources. After twenty-seven years of violent conflict, with the failure of several peace accords, the civil war finally came to an end with the death of Jonas Savimbi in 2002 and the MPLA maintaining control over the government. It is in this context that we move to analyze the initial onset of conflict in the Angolan civil war in 1975 through the lens of Collier and Hoeffler’s economic opportunity model.

II. Collier and Hoeffler’s Greed Theory

Collier and Hoeffler’s econometric model (hereafter labeled the CH model) predicting civil war onset is considered a cornerstone of empirical work in civil war research, and is based on the logic of a tradeoff between productive and appropriative economic behavior.[8] In “Greed and Grievance in Civil War”, Collier and Hoeffler present a model that predicts the outbreak of civil conflict by explaining rebellion in terms of financial opportunity that juxtaposes the economic opportunities for rebellion against grievances and its constraints.[9] The CH model explains participation in civil war as a rational decision influenced by the economic opportunity cost and the net expected utility of civil war. In the realist rational-choice model, this in turn creates a dynamic that generates opportunities for greed-rebellion, the desire for economic gain, “which is presumably sufficiently common that profitable opportunities for rebellion will not be passed up.”[10] Thus the CH model predicting civil war onset explains not only why rent-seeking rebellions form, but also why they are able to recruit by exploiting low opportunity costs, suggesting that factors determining the financial and military viability of a rebellion are more important than objective grounds for grievance. While highlighting the dichotomy between causal explanations of greed and grievance in conflict theory, in which they find no empirical evidence of a causal relationship between civil war and grievance, Collier and Hoeffler conclude:

The level, growth, and structure of income are all economically and statistically significant factors in conflict risk. […] Faster growth and [high per capita income] reduces the conflict risk because it raises the opportunity cost of joining rebellion. That primary commodity dependence increases the risk of conflict is consistent with the evident role, which primary commodities play as sources of rebel finance.[11]

Collier and Hoeffler define civil war as an internal conflict where there have been at least 1,000 combat-related deaths per annum, and where government forces and identifiable rebel groups make up at least 5 percent of the fatalities. The econometric study investigates 161 countries and 78 civil wars from 1960-1999 using a Singer and Small’s comprehensive data sets, and apply economic accounts, quantitative indicators and variables showing the circumstances in which potential rebels are able to rebel rather than the circumstances in which they want to rebel. These quantitative indicators of opportunity explain two dimensions of rebellion and conditions for profit seeking: the opportunity to finance a rebellion and the opportunity for the rebellion to recruit. According to the CH model, the opportunity to finance a rebellion is explained by, and largely depends on, the presence of lootable natural resources for the rent-seeking rebel groups to exploit, and also on external actors such as diaspora or hostile governments funding the rebellion.[12] Low opportunity cost and state weakness is measured by the size of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, which proxies earnings foregone in rebellion in the presence of low levels of mean per capita income; economic motivations to form and join a rebellion significantly grows parallel to negative economic growth. Low per capita income and low educational levels consequently allow for the exploitation of uneducated and unemployed young men with low opportunity cost when the perceived benefits outweigh the costs of rebellion. Accordingly, if the net economic benefits of rebellion are greater than the net benefits of the status quo, everyone is considered a potential rebel.[13] While low levels of social fractionalization are also proposed to substantially increase the risk of civil war, in sum, “a country’s economic opportunity structure determines the supply of insurgency for a given level of insurgency demand.”[14]

i. Quantitative Indicators for Financing Rebellion

Collier and Hoeffler suggest “the opportunities [natural resources] provide for extortion, make the rebellion feasible and perhaps even attractive.”[15] By contrasting natural resources by the ratio of primary commodity exports to GDP for each of the 161 countries, the model expects that dependency on primary commodity exports substantially increase conflict risk when primary commodity exports accounts for 33 % or more of GDP. Collier and Hoeffler propose that the endowment of unskilled labor and guns which characterizes rebel organizations is particularly suited to raise finance through the extortion of primary commodity exports. By contrasting natural resource dependency using numbers from peacetime and conflict episodes, Collier and Hoeffler conclude that “the effect of primary commodity exports on conflict risk is both highly significant and considerable.”[16] If the ratio of natural resources to GDP is accurate in the case of Angola, one should not only expect to find significantly high ratios of primary commodity exports to GDP prior to the onset of the conflict, but also find the rebel organizations mobilizing and financing their rebellion by extorting Angola’s diamonds and other lootable minerals in the time before 1975. Secondly, one should be able to observe the rebel groups manifesting and growing in size in and around the geographical areas rich in natural resources considering they are location-specific in nature.[17]

The source of funding from hostile governments and external actors such as diaspora, are also variables crucial to greed-motivated rebellion in terms of financing and making rebellion feasible. Collier and Hoeffler largely place the willingness of foreign governments to finance military opposition to the incumbent government at the time of the Cold War, when especially the continent of Africa served as a battleground for the ongoing proxy war between the Soviet Union and the United States. According to the CH model, only 11 of the 79 wars included in the analysis started during the 1990s after the Cold War ended. In other words, the Cold War would have opened up financial opportunities to rebellion enabling civil war in Angola before and in 1975. If this assumption were to be valid, one should expect to recognise and present tangible evidence that the Cold War powers, or any external actor, were actively supporting either of the fighting factions in Angola before the civil war erupted in 1975, effectively giving rebel groups incentive to rebel and ignite a civil war, and that the rent-seeking rebel groups actively exploited the Cold War powers in securing the funds and means to rebel.

ii. Quantitative Indicators for Recruitment Opportunity

Collier and Hoeffler also consider opportunities arising from atypically low cost, and suggest that greed-motivated rebellions occur when foregone income is unusually low allowing for easy recruitment. High income per capita, high levels of male secondary schooling and the positive growth rate of the economy are all factors that according to Collier and Hoeffler reduce the risk of civil conflict.[18] Again using variables in a framework of comparing peacetime and conflict episodes, they find that the conflict episodes started from less than half of the mean income of the peace episodes, and that the conflict episodes ensued during times of lower male school enrolment. According to the CH model, conflict episodes were preceded by lower growth rates—thus “the lower the rate of growth, the higher the probability of unconstitutional political change.”[19] If the combination of low opportunity cost and low level of secondary enrolment in a time of a negative economic growth explains the correlation between civil conflict and low opportunity cost, one should expect to see low levels of per capita income, high unemployment rates and a large amount of highly uneducated young men without other financial prospects in Angola before 1975.

III. Funding

To analyze the Collier and Hoeffler theory of economically motivated rebellion in the context of the Angolan Civil War, we will start with the potential sources of funding. As noted above, a critical aspect of Collier and Hoeffler’s work is the availability of funds, or economic opportunity, in order for a rebellion to appropriately function and make it an attractive alternative for potential rebels. One source of potential funding for rebel groups is a diaspora willing to support it. Other sources examined within this paper are external actors as well as natural resources.

i. Diaspora

Throughout the colonial period, Portugal transferred many Angolans to Brazil. Additionally, there is a long history of Angolans travelling to and from Portugal, South Africa and Zambia.[20] However, in the case of the Angolan civil war, there was not a great deal of Angolans abroad assisting financially with the start of the civil war. There were, however, groups of individuals in Portugal attempting to raise funds at first for the war for independence and then their own ethnic groups participating in the civil war. Guimaraes writes of the rapid abandonment of Angola by Portugal, the creation of a power vacuum, and how Angolans in Portugal quickly moved from being anti-Portuguese colonialism to being an ardent backer of their favorite rebel faction. The main actors assisting the combatants at the onset of war, however, were the neighboring states (and Cold War powers).

ii. External Actors

Beyond the diaspora, there are certainly many other sources of funding available to insurgents in the anarchic international system. In the case of Angolan diamonds, it is quite possible the international diamond markets and wholesalers (e.g. DeBeers) actually acted as a type of external actor prolonging the conflict. However, there is little evidence to suggest that this type of external actor was involved in the specific onset of the conflict. When the rebel groups were initially getting their start in the war for independence, UNITA received a small amount of military training from China and Zambia gave UNITA (unofficial) sanctuary.[21] Additionally, in a pattern that would repeat itself throughout the ensuing civil war, “In August 1962, the Congolese government places at the FNLA’s disposal a military training camp at Kinkuzu, south of Leopoldville on the way to the Angolan border.”[22]

Trust, however, was in short supply and the initial aid was not copious – which Savimbi attempted to use to his advantage in rallying people to his cause. Savimbi frequently noted that his was the only rebel group whose real leadership was actually in Angola.[23] UNITA received substantial additional aid from other nations, such as South Africa – although he later denied this. Instead, as the war continued, Savimbi chose to seemingly revel in the ideal of being funded from inside Angola through the looting of diamonds. [24]

When looking at Collier and Hoeffler’s greed-motivated rebellion thesis, one can see that an integral part of the acceleration of a conflict to rebellion and finally to civil war is the financial viability of the conflict to rebel leaders. In fact, the diminishing marginal returns to rebel labor in the context of the survival constraint is a key indicator in whether or not the rebel and government forces enter into the ‘arms race’ phase of an increasing trend of violence. What we see in the case of the Angolan Civil War of 1975, though, is an instance of several factions of rebels having already received external support in the fight for independence. The ‘arms race’ has already occurred and, therefore, this portion of Collier and Hoeffler’s work does not technically apply in the context of this civil war. Instead, a charismatic rebel leader was funded by outside sources in a proxy war, quite possibly initiated by the West, while working to maintain the myth of his political ideology and the ideal of being financed by internal methods.

Beyond the internal methods used to fund the rebels, and this being the Cold War where proxy wars were prevalent, numerous outside actors became quickly involved in the Angola conflict. As Bender has noted, “The FNLA-UNITA alliance received assistance not only from the United States, France, and Britain, but also the People’s Republic of China, Rumania, North Korea, and South Africa. The MPLA, on the other hand, secured support ranging from that of the Soviet Union and Cuba to Sweden, Denmark, and Nigeria.”[25] In January of 1975, the United States, authorized by Henry Kissinger, approved $300,000 in funding for the FNLA.[26] “The American money and encouragement meant a substantial upgrading of [FNLA] operations in 1975 against the MPLA.”[27] The United States also approved the dispatch of South African troops into southern Angola. By increasing the funding to one side of the rebel faction, giving consent to force by neighboring states, and committing CIA equipment and training, this served to create something of a proxy arms race even before independence from Portugal was officially declared on November 11. Once the MPLA gained full control over Angola’s capital of Luanda and UNITA was decimated, the Cold War powers became even more involved.

iii. Natural Resources

Another source for funding, and in many cases the primary source, is the availability of lootable natural resources. Angola was, and is, a major diamond exporter and is also endowed with oil and fertile land for agricultural exports.[28] These natural resources can be used by the state (the MPLA in this case) in order to fund projects and the government, or rebel forces can commandeer them and fund insurgency. Resources such as oil and, in particular in Angola, diamonds eventually became the funding mechanism for the Angolan civil war.[29]

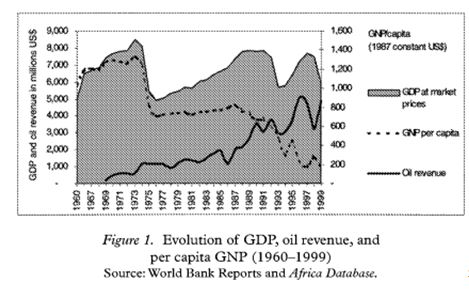

Angola as a colony of Portugal was highly involved in exporting coffee and iron ore. Per the Collier and Hoeffler model described above, we should find primary commodities accounting for more than 33% of Angola’s GDP, as well as rebel groups working to gain control of the sources of natural resources. While it is somewhat difficult to obtain information on specific rebel activities, the literature shows that UNITA, FNLA, and MPLA all were busily attacking Portuguese military forces, rather than working to accumulate resource wealth.[30] Also, as figure one shows, oil and diamonds, the resources most people consider when examining the Angola case, did not make up a substantial portion of exports in the run up to Independence.[31]

Billon goes on to note that the departure of the Portuguese colonial government “dramatically increased the vulnerability of Angola’s economy to war, owing to the low average level of income of the remaining population, the fall in skills and flexibility of the economy, and the dependence on oil to finance the import of essential commodities.”[33] This is also illustrated in Figure one as the percentage of GDP derived from oil wealth grows exponentially.

IV. Easy Recruitment/Low Opportunity Cost

In their discussion on the recruitment of rebel soldiers, Collier and Hoeffler highlight the idea of ethnic fractionalization, high unemployment, and low levels of education. All of these are different facets of the same gem of easy recruitment. As noted above, if there are no other options for making a living or feeding your family, you are much more likely to find the life of a rebel to be appealing, thus lowering your opportunity cost.

i. Ethnic Fractionalization

Collier and Hoeffler state that the less diverse a population is, there is a more likely chance of conflict occurring. This lack of fractionalization among ethnic groups allows for easier recruitment to an insurgent cause. At the time of the Angolan Civil War, as noted above, there were three main parties to the conflict with smaller groups dispersed throughout the nation. Immediately following the war for independence from Portugal, the three parties – through external urging – formed a consensus government. This tripartite arrangement was soon rendered non-functioning though due to ethnic and ideological cleavages. While there were numerous ethnic groups condensed by the Portuguese in the state of Angola, the three main ethnic parties were the Ovimbundu, the Mbundu and the Bakongo.[34]

As the civil war raged on in Angola for decades, it became a classic example of a ‘resource war.’ The warring parties used Angola’s vast resources (in addition to external funding during the Cold War period) to enable them to keep the war ongoing. However, underneath the resource motive, “the divisions between the nationalist groups were caused mainly by ethnic differences predating colonialism.”[35] Malaquias goes on to note that, “the liberation movements in Angola never succeeded in creating a united front because the MPLA, FNLA, and UNITA were never able to overcome their ethnic differences.”[36]

During the course of the Angolan civil war, the motives shifted from those of ideology to resources. As with many colonial entities, Angola had been carved up in such a way to create an entrenched system of inequality. This system of inequality, together with pre-existing ethnic disputes, led to the breakup of the uneasy alliance between the MPLA (Mbundu), UNITA (Ovimbundu), and the FNLA (Bakongo) that had been created to throw off the shackles of the colonial power. Even before the Angolan battle for independence had fully gotten off the ground, there were rumblings of racist and ethnic divisions between the factions. As Brinkman noted, the MPLA focused primarily on racism, tribalism, and foreignness when attempting to discredit their FNLA rivals.[37]

ii. Unemployment

With the infighting among the MPLA, UNITA, and FNLA before, during and immediately following independence, the Angolan economy was in shambles in 1975. Couple this with what an Institute for Security Studies report noted, “the fighting and the exodus of almost all the white settlers had left the country largely without skilled manpower,”[38] and we can easily see how the economy would be in disarray.[39] This, in turn, would lead to a decreased opportunity cost for young men when considering joining a rebel group.

The economic realm is truly where the previously held ethnic and racial divisions were cemented into place by Portuguese colonization. Guimaraes has perhaps illustrated this most clearly:

“This is how the FNLA saw the MPLA in 1962: [The MPLA] … especially recruited their members from the Angolan population classed as ‘civilized’ by the colonial regime; i.e. the half-castes and the assimilados … But they never got very far in [the regions outside urban centres]. Their lack of support was principally due to the privileged position granted to the half-castes and the assimilados by the colonialists (education, exemption from forced labor, official recognition of property ownership and of liberal professions, existing civil rights, and a standard of living far superior to that of the exploited peasant mass). This ordinance [granting these privileges] dug a social and psychological trench between them and the oppressed peasant mass.”[40]

Additionally, low-skilled workers from Portugal who were looking to escape a life of toil would come to Angola, live in the city centers and take low-skilled jobs from the local Angolans, exacerbating the divide, between the ‘civilized’ and the rural population.

When looking at the International Monetary Fund’s data, it shows that the Angolan GDP per capita in 1970 (in the middle of the war for independence) was 492.11 and it steadily increased to 594.91 in 1974 right before the Portuguese elites left the country. It immediately took a 30.6% drop in 1975 to 412.61.[41] While this certainly correlates to Collier and Hoeffler’s thesis (low wages equals a low opportunity cost for potential rebels), another way of interpreting it is that the flight of elites from Angolan society led to economic catastrophe, thereby exacerbating the already contentious relationships between the rebel parties. This caused even more difficulties economically. The three parties, MPLA, FNLA, and UNITA knew a great deal about rallying ethnic groups to their causes, guerilla fighting, and garnering international support but not nearly as much about the compromises necessary to effectively run a country together.

iii. Education

The Collier and Hoeffler model associates GDP with education as a way of trying to look into the potential individuals have for economic opportunity and advancement. The average level of Angolan education in the 1970s, like most colonies, was very low. Due to the class and ethnic stratification brought on by Portuguese control schemes, huge segments of the population were unable to read or write.[42] There were, however, certain racial/ethnic groupings that were somewhat assimilated into Portuguese society and allowed the opportunity to study. Ethnic divisions ran throughout Angolan society. Guimaraes states, “…one of the characteristics of the rivalry that emerged between the two main Angolan anti-colonial movements, the MPLA and the FNLA, was a hostility between, on the one hand, mesticos (mixed race) and assimilados (‘assimilated’ locals given special legal status) and, on the other, Africans who had not been co-opted by colonial society.”[43]

V. Discussion

On balance, the onset of the Angolan Civil War would appear to be more highly related to ethnic divisions as opposed to resource accumulation. As the ethnic groups had been divided primarily between rural and urban populations, this created an easily manipulated rift between the rural Ovimbundu and Bakongo and the urban Mbundu populations. Collier and Hoeffler would look to see low GDP, funding from external actors, low education, high unemployment, and lootable resources. In the case of Angola, we certainly find these articles evidenced. However, the underlying grievance of years of institutionalized racial and ethnic tensions – which formed the basis for the educational and economic system present in pre-civil war Angola – truly provide the common thread that ties the majority of this evidence together. The CH model would appear to more sufficiently explain the duration and recurrence of the civil war.

VI. Conclusion

Le Billon noted that, “oil and diamonds are neither the cause nor the only motivation for the Angolan conflict.”[44] What we have sought to show through the analysis presented in this paper is that while the Collier and Hoeffler model goes far in explaining many aspects of conflict, it does not sufficiently explain the onset of civil war in Angola in 1975. This is important for further study as it emphasizes the fact that while there are similarities between conflicts, each conflict is in many ways unique and should be examined in its own right. While the economic opportunity so central to the CH model does exist in the Angolan context, we do not find that the correlation between economic motivations and civil war onset provides a strong causal explanation. Based on our findings, Collier and Hoeffler’s economic opportunity theory does not sufficiently take into account ethnic and racial divisions, which hold the lion’s share of culpability for the 1975 Angolan Civil War.

Bibliography

- Aftergood, Steven. “UNITA, National Union for the Total Independence of Angola.” UNITA União Nacional Pela Independência Total De Angola. Federation of American Scientists, 7 May 2003. Web. 19 July 2012. <http://www.fas.org/irp/world/para/unita.htm>.

- “Angola.” UN Data. United Nations Statistics Division, n.d. Web. 19 July 2012. <http://data.un.org/CountryProfile.aspx?crName=Angola>.

- Bender, G. J. “The Eagle and the Bear in Angola.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 489.1 (1987): 123-32. Print.

- Birmingham, David. Frontline Nationalism in Angola & Mozambique. Trenton, NJ: Africa World, 1992. Print.

- Brinkman, Inge. “War and Identity in Angola.” Lusotopie (2003): 195-221. Lusotopie. Web. 15 July 2012. <http://www.lusotopie.sciencespobordeaux.fr/brinkman2003.pdf>.

- Brittain, Victoria. Death of Dignity: Angola’s Civil War. London: Pluto, 1998. Print.

- Cillers, Jakkie. “Business & War in Angola.” Review of African Political Economy 28.90 (2001): 636-41. Print.

- Collier, P., and A. Hoeffler. “Greed and Grievance in Civil War.” Oxford Economic Papers 56.4 (2004): 563-95. Print.

- Collier, Paul, Anke Hoeffler, and Måns Söderbom. “On the Duration of Civil War.” Journal of Peace Research 41.3 (2004): 253-73. Print.

- Cooper, Tom, and Pedro Alvin. “Angola since 1961.” Angola since 1961. Air Combat Information Group, 10 Feb. 2008. Web. 19 July 2012. <http://www.acig.org/artman/publish/article_181.shtml>.

- Cornwell, Richard, and Jakkie Potgieter. “African Conflict Prevention Programme (ACPP).” Angola – Endgame or Stalemate. Institute for Security Studies, Apr. 1998. Web. 15 July 2012. <http://www.issafrica.org/programme_item.php?PID=6>.

- “Country Data Report for ANGOLA, 1996-2010.” Worldwide Governance Indicators. The World Bank, n.d. Web. 13 July 2012. <http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/pdf/c4.pdf>.

- “EconStats : Angola GDP per Capita, Current Prices Weo.” EconStats : Angola GDP per Capita, Current Prices Weo. International Monetary Fund, n.d. Web. 15 July 2012. <http://www.econstats.com/weo/CV004V008.htm>.

- Frynas, J. G., and G. Wood. “Oil & War in Angola.” Review of African Political Economy 28.90 (2001): 587-606. Print.

- Grossman, H. I. “Kleptocracy and Revolutions.” Oxford Economic Papers (1999): 267-83. Print.

- Guimarães, Fernando Andresen. The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2001. Print.

- Heywood, Linda. Contested Power in Angola, 1840s to the Present. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester, 2000. Print.

- James, W. Martin. A Political History of the Civil War in Angola, 1974-1990. New Brunswick, N.J., U.S.A.: Transaction, 1992. Print.

- Knudsen, C. M., and I. W. Zartman. “The Large Small War in Angola.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 541.1 (1995): 130-43. Print.

- Le Billon, Phillipe. “Angola’s Political Economy of War: The Role of Oil and Diamonds.” African Affairs 100 (2001): 55-80. Print.

- Le Billon, Phillipe. “The Political Ecology of War: Natural Resources and Armed Conflicts.” Political Geography 20 (2001): 561-84. Print.

- Lewis, Lloyd R. “Angola Diamond Mining And War.” Angola Diamond Mining and War. American University; Trade and Environment Database, 14 June 1997. Web. 11 July 2012. <http://www1.american.edu/ted/ice/angola.htm>.

- Malaquias, Assis. “Ethnicity and Conflict in Angola: Prospects for Reconciliation.” Angola’s War Economy: The Role of Oil and Diamonds. By Jakkie Cilliers and Christian Dietrich. Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 2000. 95-113. Print.

- “Namibia.” UNdata. United Nations Statistics Division, n.d. Web. 13 July 2012. <http://data.un.org/CountryProfile.aspx?crName=Namibia>.

- Sambanis, Nicholas. “Using Case Studies to Expand Economic Models of Civil War.” Perspectives on Politics 2.02 (2004): 269-73. Print.

- Tinajero, Sandra. A Study of Migrant Remittance Flows to Angola from Portugal and South Africa, and Their Current Use and Impact on Receiving Households. Publication. International Organization for Migration, June 2009. Web. July 2012. <http://www.iom.int/jahia/webdav/shared/shared/mainsite/media/docs/reports/angola_final_report_remittance_study.pdf>.

- Westing, Arthur H. Global Resources and International Conflict: Environmental Factors in Strategic Policy and Action. Oxford [Oxfordshire: Oxford UP, 1986. Print.

Appendix I

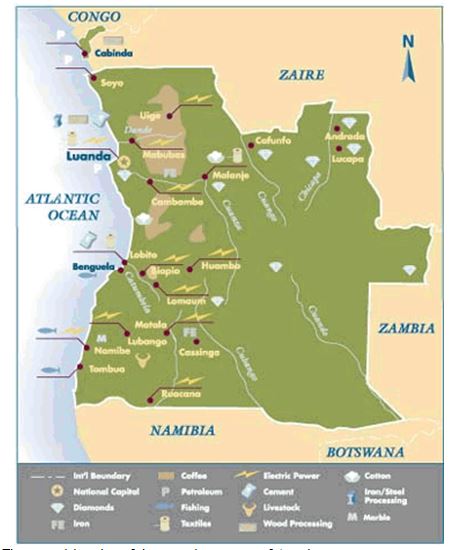

The general location of the natural resources of Angola:

Source: Lewis, Lloyd R. “Angola Diamond Mining And War.” Angola Diamond Mining and War. American University; Trade and Environment Database, 14 June 1997. Web. 11 July 2012. <http://www1.american.edu/ted/ice/angola.htm>.

Appendix II

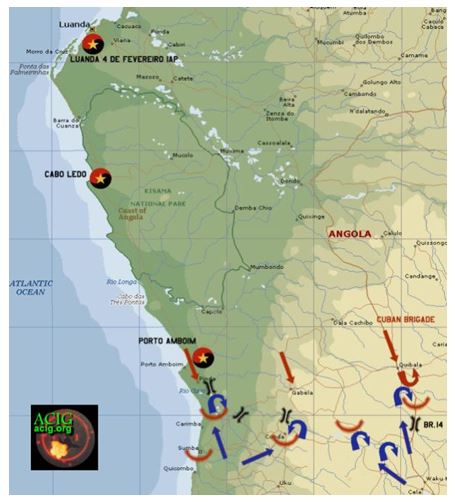

Map showing the area, 125 miles south of Luanda, where MPLA/Cuban forces were able to repel the S. African/UNITA advance:

Source: Cooper, Tom, and Pedro Alvin. “Angola since 1961.” Angola since 1961. Air Combat Information Group, 10 Feb. 2008. Web. 19 July 2012. <http://www.acig.org/artman/publish/article_181.shtml>.

Appendix III

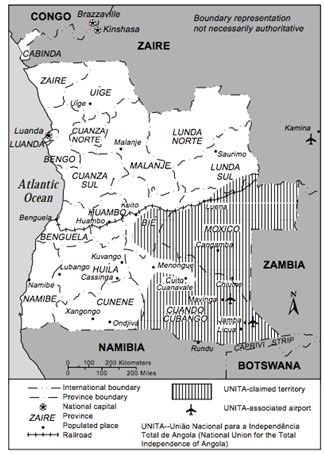

Map showing UNITA-claimed territory in 1988. UNITA’s strength has always been in the rural southeast of Angola:

Source: Aftergood, Steven. “UNITA, National Union for the Total Independence of Angola.”UNITA União Nacional Pela Independência Total De Angola. Federation of American Scientists, 7 May 2003. Web. 19 July 2012. <http://www.fas.org/irp/world/para/unita.htm>.

[1] Westing, Arthur H. Global Resources and International Conflict: Environmental Factors in Strategic Policy and Action. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford UP, 1986.

[2] Frynas, J. G., and G. Wood. “Oil & War in Angola.” Review of African Political Economy 28.90 (2001): 587-606.

[3] Note that UNITA, the main opposition was lead by Jonas Savimbi while, Edwardo Dos Santos headed MPLA, a political party which has been in power since independence in 1975.

[4] Frynas, J. G., and G. Wood. “Oil & War in Angola.” Review of African Political Economy 28.90 (2001): 587-606.

[5] Ibid.

[6] James, W. Martin. A Political History of the Civil War in Angola, 1974-1990. New Brunswick, N.J., U.S.A.: Transaction, 1992.

[7] Cornwell, Richard, and Jakkie Potgieter. “African Conflict Prevention Programme (ACPP).” Angola – Endgame or Stalemate. Institute for Security Studies, Apr. 1998. Web. 15 July 2012. : 3 <http://www.issafrica.org/programme_item.php?PID=6>.

[8] Grossman, H.I. 1999. Kleptocracy and Revolutions. pp. 267-283. Oxford Economic Papers.

[9] Collier, P., and Hoeffler, A. 2004. “Greed and Grievance in Civil War”, pp. 563-595. Oxford Economic Papers.

[10] Ibid, 564.

[11] Ibid, 588.

[12] Collier, et al.. “Greed and Grievance in Civil War. ANDRE SIDE

[13] Sambanis, N. 2004. ”Using Case Studies to Expand Economic Models of Civil War”, pp. 269-273. Perspective on Politics

[14] Ibid, 261.

[15] Sambanis, N. 2004. ”Using Case Studies to Expand Economic Models of Civil War”, pp. 269-273. Perspective on Politics

[16] Collier et al. 588

[17] Ross, M. “How Do Natural Resources Influence Civil War? Evidence from Thirteen Cases”, pp. 35-77. International Organization. 40

[18] Collier et al. 11

[19] Alesina, A., S. Oetzler, N. Roubini and P. Swagel. 1996. ‘Political Instability and Economic Growth’, pp. 189-211. Journal of Economic Growth.

[20] Tinajero, Sandra. A Study of Migrant Remittance Flows to Angola from Portugal and South Africa, and Their Current Use and Impact on Receiving Households. Publication. International Organization for Migration, June 2009.

[21] James, W. Martin. A Political History of the Civil War in Angola, 1974-1990. New Brunswick, N.J., U.S.A.: Transaction, 1992.

[22] Guimarães, Fernando Andresen. The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2001. : 64

[23] James, W. Martin. A Political History of the Civil War in Angola, 1974-1990. 143, New Brunswick, N.J., U.S.A.: Transaction, 1992.

[24] Ibid, 148.

[25] Bender, G. J. “The Eagle and the Bear in Angola.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 489.1 (1987): 123-32.

[26] Brittain, Victoria. Death of Dignity: Angola’s Civil War. London: Pluto, 1998.

[27] Ibid, 2.

[28] Please see Appendix 1 to view a map of Angolan natural resources.

[29] Malaquias, Assis. “Ethnicity and Conflict in Angola: Prospects for Reconciliation.” Angola’s War Economy: The Role of Oil and Diamonds. By Jakkie Cilliers and Christian Dietrich. Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 2000. 95-113.

[30] Please see Appendix II to view a map of where the main thrust of the fighting was when the Civil War began in 1975.

[31] Le Billon, Phillipe. “Angola’s Political Economy of War: The Role of Oil and Diamonds.” African Affairs 100 (2001): 55-80. Web.

[32] Ibid, 60.

[33] Ibid, 59.

[34] Guimarães, Fernando Andresen. The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2001.

[35] Malaquias, Assis. “Ethnicity and Conflict in Angola: Prospects for Reconciliation.” Angola’s War Economy: The Role of Oil and Diamonds. By Jakkie Cilliers and Christian Dietrich. Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies, 2000. 95-113. : 95

[36] Ibid, 103.

[37] Brinkman, Inge. “War and Identity in Angola.” Lusotopie (2003): 195-221. Lusotopie. Web. 15 July 2012. <http://www.lusotopie.sciencespobordeaux.fr/brinkman2003.pdf>.

[38] Cornwell, Richard, and Jakkie Potgieter. “African Conflict Prevention Programme (ACPP).” Angola – Endgame or Stalemate. Institute for Security Studies, Apr. 1998. Web. 15 July 2012. <http://www.issafrica.org/programme_item.php?PID=6>. : 3

[39] In August 1976, more than 80 percent of the Agricultural plantation – Angola’s main source of export income – had been abandoned by their Portuguese owners; only 284 out of 692 factories continued to operate; more than 30,000 medium-level and high-level managers, technicians, and skilled workers had left the country; and 2,500 enterprises had been closed (75 percent of which had been abandoned by their workers). ). – per, Angola: A Country Study, United States Marines publication: http://www.marines.mil/news/publications/Documents/Angola%20Study_3.pdf

[40] Guimarães, Fernando Andresen. The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2001. : 26

[41] “EconStats : Angola GDP per Capita, Current Prices Weo.” EconStats : Angola GDP per Capita, Current Prices Weo. International Monetary Fund, n.d. Web. 15 July 2012. <http://www.econstats.com/weo/CV004V008.htm>.

[42] Guimarães, Fernando Andresen. The Origins of the Angolan Civil War: Foreign Intervention and Domestic Political Conflict. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2001.

[43] Ibid, 25.

[44] Le Billon, Phillipe. “Angola’s Political Economy of War: The Role of Oil and Diamonds.” African Affairs 100 (2001): 55-80. : 79

—

Written by: Erik Sande, Sakilye Amos, Ina Holst-Pedersen Kvam

Written at: University of Oslo

Written for: Kendra Dupuy, Stephan Hamberg

Date written: July 2012

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Angolan Civil War: Conflict Economics or the Divine Right of Kings?

- Do Coups d’État Influence Peace Negotiations During Civil War?

- Were ‘Ancient Hatreds’ the Primary Cause of the Yugoslavian Civil War ?

- The Mobilisation of Sectarian Identities in the Syrian Civil War

- Agonizing Assemblages: The Slow Violence of Garbage in the Yemeni Civil War

- Ripening Conflict in Civil Society Backchannels: The Malian Peace Process (1990–1997)