Ugandan Anti-Terror Policies: How Securitization, Democratization and Aid Distribution Intersect in African Politics

“We will direct every resource at our command — every means of diplomacy, every tool of intelligence, every instrument of law enforcement, every financial influence, and every necessary weapon of war — to the destruction and to the defeat of the global terror network.” – George W. Bush, 9/20/01

Western world discourse has been saturated with the attacks of September 11th 2001 and the subsequent “War on Terror”, which has led to a sharp increase in the securitization of development issues and a significant impact on foreign aid and development policies. Consequently, discursive frameworks that guide Western world dialogue and policies relating to Africa have shifted from gentle, humanitarian fabrics to ones of harsher, global insecurity textures.

This change in global political fabric has had a significant impact on African politics. In repositioning the concept of development deeper in the discursive framework of global insecurity, the implicit importance of Western world conditionalities linked to aid distribution have also shifted in response, mainly from good governance to behaviour supportive of the “War on Terror”. In this paper, Uganda will serve as a case study to demonstrate that, although there is an explicit good governance conditionality structure for aid distribution from the Western world, aid is becoming increasingly untied from democratic improvements. Despite a regression in the Ugandan democratization process, aid has continued to flow into the country over the past decade due a new and implicit “War on Terror” conditionality structure. The growing securitization of development has therefore indirectly undermined Uganda’s democratization process through Western world donors’ promotion of supportive “War on Terror” behaviour as of greater import than good governance.

The securitization of development is best understood by looking at the fundamental roots of securitization theory, which sprouted from the Copenhagen School of Security Studies (Williams, 2008). Founding theorists within this institution view security as a creation of discursive construction rather than as an objective condition (ibid). Issues can therefore be securitized through speech and, it is posited, shifted from the realm of political normalcy to one of emergency interventions where extraordinary means are legitimated. In practice however, issues rarely jump directly from normalcy to extremism. As Abrahamsen (2005) notes,

“rather than emergency action, most security politics is concerned with more mundane management of risk, and security issues can be seen to move on a continuum from normalcy to worrisome/troublesome to risk and to existential threat” (p. 59).

Consequently, securitization offers better insight if visualized as a spectrum or gradual process where issues fluctuate between, although never realizing, states of complete securitization and desecuritization.

This spectrum is important to consider when analysing the securitization of Western world development issues, as the security-development nexus appeared long before the events of 9/11 (Hettne, 2010; Cooper, 2005; Duffield, 2010). As Duffield (2010) highlights the evolution of securitization, he demonstrates that “from communism to terrorism, […] poverty has been monotonously rediscovered as a recruiting ground for the moving feast of strategic threats that constantly menaces the liberal order” (p. 61). This perception has intensified acutely since 9/11, as failed states and terrorism, viewed as distant and indirect security threats during the Cold War era, are now seen (and have been constructed) as direct and crucial threats (Newman, 2009).

Some examples of this heightened securitization can be seen in the evolution of discourse and policies of important donors. In the UK in 2005, the UK Department for International Development (DFID) stated that

“security and development are linked…poverty, underdevelopment and fragile states create fertile conditions for conflict and the emergence of new security threats, including international crime and terrorism” (Newman, 2009, p. 436).

Similarly, in the US in 2002, the Millennium Challenge Account (MCA) was established to “allocate aid based on previous good performance criteria and on presumed efforts by recipient countries in the war on terror” (Cammack et al., 2006, p.33). It is therefore important to consider this heightened securitization when analysing why policy makers have pushed to cancel debt and increase aid for specific countries in the past decade (Cooper, 2005).

As mentioned previously, “good governance” continues as Western world donors’ explicit goal in aid distribution. This particular form of conditionality first appeared in a 1989 World Bank report that identified “bad governance” as the cause for stagnant and negative economic growth on much of the African continent during the 1980s (Osman, 2008). Although “good governance” is defined generally as the state’s ability to stimulate development, due to the concurrent end of the Cold War, democracy was the only political regime touted as conducive to this aim (Sande Lie, 2010). Consequently, this contributed to a “third wave” of democratization in Africa (Lynch & Crawford, 2011).

Unfortunately, much like the preceding era of structural adjustment, democracy expanded in Africa with little or no reduction in poverty or improvement in development (Osman, 2008). Although the performance of political rights fared better than material benefits (Lynch & Crawford, 2011), they too were undermined in the 1990s as the democratic practices of multiple countries were seen as either significantly damaged or suspect by the early 2000s (Abrahamsen, 2000; Fukuda-Parr et al., 2002).

Democracies that had previously adopted structural adjustment programmes often had the most unimpressive results, as they were forced to embark on political and economic liberalization programmes simultaneously (Adetula, 2011). Although originally peddled by Western world donors as two sides to the same coin of neoliberal reform, enactment of political and economic liberalization has since been debated as an unwise policy since they cannot be achieved concurrently (Abrahamsen, 2000, p. 113). More specifically, the austere type of economic reforms required by donors and creditors served to undermine the state’s domestic support base (Adetula, 2011). Leaders steeped in the tradition of one-party systems were therefore easily enticed back to authoritarian regimes or into “exclusionary democracies” (Abrahamsen, 2000) where neo-patrimonial or ethnic politics served to legitimate their rule, yet failed to incorporate the majority of citizens’ demands (Fritz, 2007).

Although this challenge of dual economic and political reforms has had lasting effects on the democratization process in Africa, this paper will argue that democracy was further undermined after 9/11 by a shift to a paradigm of security-first aid conditionality.

Uganda offers an excellent case study in this regard, as Museveni, Uganda’s leader since 1986, was viewed as the “golden protégé” of African leaders in the late 1990s (Furley, 1999, p. 14). So much so that when the World Bank, IMF and other donor and lending institutions created their first major debt relief scheme, Uganda was the first recipient through the poverty reduction strategy paper (PRSP) process. Since then, the country has seen economic growth “averaging about 7.7 percent a year over the 1997-2007 period” (Ssewanyana et al., 2011, p. 51) and has therefore remained a donor darling despite Museveni’s increasingly undemocratic behaviour and policies (Fisher, No Date). From rampant corruption to tainted elections, Ugandan democracy has undeniably regressed since its promising beginnings (Mwenda, 2007; Tangri & Mwenda, 2010). And although roughly half the of the Ugandan government’s budget is financed by foreign aid (Furley, 1999; Mwenda, 2007), there is little international donor willingness to use this as leverage for democratic governance, despite their explicit mandate (Mwenda & Tangri, 2010). This paper will explore why this is the case, by first reviewing securitization theory and the third wave democracy at greater length, then investigating aid distribution trends as they relate to “War on Terror” politics, and finally understanding the intersection of these concepts within the specific context of Uganda.

Securitization Theory

As mentioned previously, although the Copenhagen School subscribes to a Weber-like dichotomy of ideal types (securitized and desecuritized), securitization is in fact better conceptualized as a continuum. History validates this claim, looking at development discourse and policy from the colonial to present-day period. As Hettne (2010) points out, while security was a main pillar of ‘development’ strategies in the colonial era, it continued as a post-colonial concern within the Marshall Plan, and it is now most explicitly stated in present-day development policies that speak of the War on Terror and global terrorist threats. Therefore, irrespective of the objective changes in security conditions, development issues have always been securitized at different intensities at different points in time. However, the post-9/11 environment has witnessed an exceptionally acute heightening of security in Western world development discourse and policies (Duffield, 2010; Cooper, 2005).

The Bush administration in the United States and its main “War on Terror” ally, the Blair administration in the United Kingdom, have both subscribed to the democratization agenda through their support of World Bank good governance policies. Their political discourse and bilateral development policies, on the other hand, demonstrate a heightened level of securitization and therefore imply that supportive “War on Terror” behaviour is in fact of primary importance to aid distribution. For example, under the Bush administration, US official aid spiked to US$27.5 billion in 2005, from $19.7 billion in 2004, with almost all of the additional aid going towards reconstruction and development in Iraq (Cammack et al., 2006). This denotes “the beginnings of a shift in priorities – from ‘traditional’ aid activities in a wide range of countries (with less emphasis on selectivity) to a greater focus on MCA-eligible countries” (Harmer & Macrae, 2004). In light of the MCA’s mandate, as previously discussed, this effectively means that while the US has increased development aid, much of it will now be directed according to the priorities of the “War on Terror”.

When the Blair administration came into power in 1997, the British foreign secretary heralded a new approach to foreign policy in which Britain would become a “force for good in the world” and “the champion of the oppressed” (Abrahamsen, 2005, p. 61). Since the events of 9/11, however, the justification for the disbursement of development aid has made a notable shift away from aiding African development towards aiding Britain’s global security interests (Abrahamsen, 2005). This reallocation of aid justification is demonstrated by the soaring political role of DFID, which, as mentioned previously, views security and development as having an inherent link with underdevelopment, creating fertile conditions for new global security threats (Newman, 2009, p. 436). Abrahamsen notes that although a global fear of poverty is not new, Blair’s administration has explicitly linked African, international security with terrorism (Abrahamsen, 2005, p. 75). As a result, this connection has been taken up by the current British administration in its release of the first UK National Security Strategy in 2008, where it argued that poverty was a “key driver” of global insecurity (Newman, 2009, p. 435).

Although many authors (Abrahamsen, 2005; Duffield, 2010) have investigated the politics and reasoning behind the increasing securitization of the Western world’s perception of development issues, what follows will deconstruct its influence on African politics instead. More specifically, by focusing on the selectivity in how foreign aid is distributed as a result of growing securitization, this paper will demonstrate how an acute increase in securitization is now one of the biggest challenges to further democratization in Africa.

Third Wave Democracy

In the decade prior to 9/11, despite the disastrous effects of the structural adjustment period, Western world donors still viewed neoliberal reforms as the necessary path to economic growth and development (Adetula, 2011). Intrusive economic interventions had fallen out of favour in the late 90’s, however, as they came to be regarded as counterproductive to some of the key tenets of democratic progress: accountability and ownership. Consequently, most Western world donors shifted to pursue “good governance” programs, such as the World Bank and IMF’s PRSP initiative. While this program promoted state ownership of economic reforms through donor-recipient “partnerships”, and accountability through civil society consultation (Cammack, 2004), the inherently lopsided nature of donor-recipient relationships still allowed donors to push for neoliberal reform in a less intrusive manner.

Despite this continued neoliberal push, democratization did progress at the beginning of the “third wave” period. Yet the austerity of economic liberalization and its negative effects on social services and development resources for the poor eventually caught up with African leaders. As dissatisfaction amongst voters grew and elections loomed, many leaders fell back on the strategies they were most familiar with from previously authoritarian regimes. Although good governance conditionalities ensured elections continued, true democracy receded into its exclusionary form (Abrahamsen, 2000) as incumbent leaders sought to consolidate power and entrench themselves through undemocratic means, such as the manipulation of ethnic identity, pervasive clientelism and military control (Lynch & Crawford, 2011).

In summary, as Lynch and Crawford (2011) note, there are numerous criticisms of how development aid simultaneously helped to introduce and weaken democracy in Africa since the 1990s – economic reforms being one of them. After 9/11, however, an acute increase in the securitization of the Western world’s perception of development issues has further undermined democracy in many African countries. Consequently, although the thread of democratic accountability had become increasingly untied from aid in the 1990s, it has now become completely undone in some countries due to an era of global insecurity and terrorist threats.

Aid Distribution Trends vs. War on Terror Politics

Before discussing the distribution of aid as it relates to securitized Western world discourses, it is worthwhile to revisit the conceptualization of securitization as a spectrum. As previously discussed, issues move discursively between, yet generally never attain, full securitization or full desecuritization. It is important to note that security responses move along a similar spectrum, from more liberal strategies of incorporation and management of threats to more serious and illiberal strategies of temporary control and invasions of states (Abrahamsen, 2005). This paper looks at development aid distribution as a security response, which falls somewhere in the middle of the spectrum.

In analysing trends in aid disbursement, such as geography, levels and implicit conditionalities, a myriad of connections can be drawn to African related War on Terror policies. Security-related considerations such as the presence of foreign terrorist groups, shared borders with a state sponsor of terrorism, and membership within the Coalition of the Willing, have played a large role in the distribution of aid on the African continent (Aning, 2010). General international public support of the War on Terror has even become a factor, as witnessed by the US withholding donor assistance to Nigeria when the Nigerian president made critical remarks on the US invasion of Iraq (Carmody, 2005, p. 100). General domestic public support has similarly become important, as witnessed by the increase in dramatic, public and often arbitrary pursuits of potential terrorists in Kenya as a “perfunctory response[] to American pressure” (Prestholdt, 2011).

When looking at trends in the levels and amount of aid disbursed, although US aid has increased on a whole after 9/11, shifts in those countries receiving increasing amounts of aid, such as Afghanistan and Iraq, have been drastic and “reflect emerging post-9/11 security realities, most notably the demands of the WOT [War on Terror]” (Aning, 2010, p. 13). The UK has similarly redirected development resources to states viewed as War on Terror allies, with Pakistan, for example, seeing a five-fold increase in development assistance from 2001 to 2003/04 (Aning, 2010). In regards to Africa, due to the DAC’s widening interpretations of development aid qualifications in 2004, almost all of the US aid increases in Africa were allocated to security sectors. These sectors additionally fell within African countries whose support for the War on Terror had been enlisted (Ibid.). As a result, while there have been increases in global aid, developing regions that are less strategic to the War on Terror have been marginalized in aid priorities (Carmody, 2005).

Finally, in terms of implicit conditionalities, in addition to anti-terror laws and legislation, the US has exacted other important African policy concessions through threats of aid suspension or incentives of aid increases, such as Article 98 agreements. Since the events of 9/11, the US has invoked a short-term application of the American Service Members Protection Act (Presholdt, 2011). This piece of legislation disallows military aid disbursements to countries that support the International Criminal Court (ICC) without their signing of a separate Article 98 agreement that prohibits the surrendering of US citizens to the ICC (ibid). Various African countries rejected these agreements, such as Kenya, Mali, Namibia, Niger and Tanzania, and saw temporary cuts in US aid as a result (ibid).

Promises of increased aid or threats of aid suspension have therefore played a crucial role in dictating War on Terror support in the developing world, demonstrating that the increased securitization of the Western world’s perception of poverty and development has significantly impacted African policies. In addition to specific African anti-terrorist policies, the Ugandan case study will offer a more detailed understanding of how this increased securitization has and will have a more lasting impact on African democratic regimes more generally.

The Ugandan Case Study

Foreign Aid

During the 1990s, Uganda was hailed as a post-conflict donor success story due to the new President’s stable and progressive rule (Mwenda, 2007). Aid from the major multilateral lending institutions and other Western world donors started arriving for Yoweri Museveni almost immediately after his incumbency started, at which point the Ugandan economy posted an average annual GDP growth rate of 6% until the end of the 1990s (Furley, 1999, p. 13). Consequently, there was a “generous and continuous” (ibid) flow of aid during the same period with massive amounts of multilateral debt relief in 1998 after Uganda, in conjunction with donors, spawned and successfully completed the first PRSP (Callaghy, 2001).

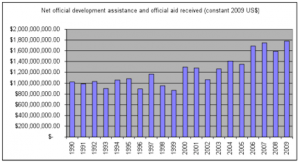

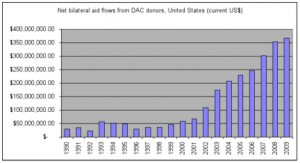

After 9/11, Uganda’s net official development assistance and aid started another upward trend with a drastic push from US bilateral aid flows in particular.

(World dataBank, 2012)

(World dataBank, 2012)

According to Keane et al. (2010), the increase in aid commitments to Uganda during the 2000s has, in fact, been mainly driven by bilateral aid. The biggest bilateral donors have been the US and the UK, although the World Bank remained the largest donor over that period (p. 31).

Additionally, the strong relationship between these donors and the Ugandan President is demonstrated through Uganda’s positive integration in global politics. As Tangri and Mwenda (2010) highlight, “Uganda hosted the Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in 2007 and in 2008 was elected to a seat on the Security Council” (p. 46). Consequently it comes as no shock that the World Bank and IMF now showcase Uganda as one of the most successful reformers in Africa (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010).

But what does “success” look like if, by 2003, “donors financed one-half of total public expenditure and nearly the government’s entire development budget” (p. 45)? Considering its relatively influential position as Uganda’s largest donor, one would assume the World Bank’s conception of “success” is relatively in balance with the good governance conditionality framework. Yet the following section will deconstruct and investigate the veracity of this conjecture.

The Democratization Process

Uganda’s democratization process has oscillated in both speed and direction over Museveni’s roughly 25 year reign. In the early years, there was mostly progress at a varied pace. When Museveni came to power in 1986, he stressed to Ugandan citizens that he was committed to “grassroots democracy” and that his uprising – the National Resistance Movement (NRM) – was a “people’s movement” for all Ugandans (Furley, 1999). After a long consultative process that involved “every institution, every class of society, every area” (p. 3), Museveni created a new constitution that was successful in imposing a number of democratic guarantees as well as checks and balances against the misuse of political power (Mwenda, 2007). He then introduced an electoral process soon after with the first elections judged as generally free and fair (Furley, 1999).

Additionally, due to decades of political strategies of ethnic exclusion and marginalization under the rule of previous dictators, Museveni committed to building a regime that eliminated all forms of sectarianism (Lindemann, 2011). Consequently, progress was made in transforming the political, military, economic and territorial spheres to eliminate ethnic and regional imbalances (ibid). The “Movement”, as Museveni’s regime was later named, even went so far as to initially ban political parties in an effort to erase ethnic divisions from national politics (Furley, 1999). Consequently, the first few Ugandan elections were held between individual candidates with individual, non-ethnic platforms.

Within the territorial sphere, Museveni also made great strides to decentralize power to the local level. After the new constitution was passed, all matters except security, national planning and projects, immigration and foreign affairs decisions, were devolved to Local Councils. This served as means to round off the democratization process by offering all Ugandans more inclusion in the political process (Lindemann, 2011).

Nevertheless, upon entering the 2000s, Uganda’s democratization process veered off course and was hastily thrown into reverse (Mwenda, 2007; Tangri & Mwenda, 2010; Lindemann, 2011). For instance, although Museveni had stated that the “problem of Africa in general and Uganda in particular is not the people but leaders who want to overstay in power” (As cited in Tangri & Mwenda, 2010, p. 31-32), he has since then made sweeping changes to the constitution that include removing the two term limit on the presidency (Mwenda, 2007). As a result, he is now in his fourth consecutive, five year term as president, making his reign longer than the combined tenure of all presidents that came before him since Uganda’s independence in 1962 (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010, p. 31). Furthermore, elections in 2001, 2006 and 2011 were marred by intimidation and electoral malpractice (Mwenda, 2007).

Similarly, promises of ethnic inclusionary politics were either broken or never fulfilled as national government posts have remained skewed in favour of the ethnic groups that founded Museveni’s NRM (Lindemann, 2011). These ethnic groups have maintained an even tighter reign over the Ugandan military (ibid), as Museveni has tellingly stated that because it is “his army”, it would never follow a leader from the political opposition (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010). The liberalization of Uganda’s economy has also equally rewarded Museveni’s ethnic groups with jobs and national assets as a means of patronage (Lindemann, 2011).

Beyond these transgressions, there is now also the added perception that widespread corruption is rampant in the Ugandan political regime. In May 2009, Transparency International echoed this chorus by listing Uganda as the third most corrupt country in the world (Ssewanyanna et al., 2011). The appointment of Museveni’s son as the commander of Special Forces (Tangri & Mwenda, 2010) and the kickback scandals surrounding other family members (Lindemann, 2011) provide examples of where and how this perception began.

Therefore, although foreign aid continues to climb and the World Bank continues to showcase Uganda as one of Africa’s most successful reformers, Uganda’s democratization process can only be characterized as one of good governance backsliding. Uganda’s positive and sustained economic performance has provided some cushion to good governance aid conditionality since Museveni took power in 1986. Given the constancy of its performance over the past few decades, however, it seems unlikely that successful economic growth would explain the renewed upward trend in Western world aid since the beginning of the 2000s. As the next section will show, Uganda’s recent repositioning as a dedicated War on Terror ally offers compelling reasoning for this disconnect.

War on Terror Support and Policies

Although the US had strategic security interests in Uganda prior to 9/11 due to its shared border with Sudan – one of the countries on the US list of states sponsoring terrorism (Furley, 1999) – donor dialogue now stresses Uganda’s reliability in the War on Terror instead (Fisher, 2012). According to Tangri and Mwenda (2010), “for the US and the UK, Museveni is a key leader and important partner in combating terrorism and Islamic extremism in the region” (p. 46). These perceptions have been reinforced and sometimes purposely constructed by Uganda’s adoption of anti-terrorism legislation, unwavering support for the War on Terror, and construction of LRA links to al-Qaeda (Fisher, 2012).

Museveni introduced the Prevention of Terrorism Act to the Ugandan parliament in 2002 (Fisher, 2012). Unlike other countries where human rights organizations and NGOs stalled or blocked similarly oppressive anti-terrorism acts, the Ugandan bill was passed quickly and without controversy (ibid). Similarly, unlike many other African governments, Uganda willingly signed an Article 98 agreement with the US in 2003 (ibid). In light of previous manipulations of parliament through coercive dealings (Mwenda, 2007), it is reasonable to question how much political manoeuvring on Museveni’s part was needed to ensure this legislation passed.

Museveni has also been an excellent donor diplomat. Although he has, on occasion, criticized donors in general, these comments have never been addressed towards the US specifically and Museveni has never expressed any doubt regarding the appropriateness or effectiveness of US counter-terrorism policies in the region (Fisher, 2012). Additionally, his government has made every effort to highlight Uganda’s support for the War on Terror – through its pursuit of the LRA terrorist group – in donor discussions (ibid). As Fisher (2012) emphasizes, one former diplomat noted that during a mid-2000s meeting with Museveni, the President constantly redirected the conversation from democratic issues towards the topic of LRA-related terrorism.

This serves to highlight yet another Ugandan strategy used in bolstering the country’s image as an important and devoted War on Terror ally. Despite having absolutely no association with Islamic fundamentalism, the Ugandan government has launched a dedicated campaign to position the LRA rebellion as a product of al-Qaeda terrorism (Fisher, 2012). In a 2003 speech to the Council on Foreign Relations, Museveni stated that the LRA had been trained by al-Qaeda. He has then used this connection to speak of “Uganda’s War on Terror”, in an attempt to build international perceptions of Uganda’s front-line role in the US-led “War on Terror” (ibid).

In summary, within a global era of increasingly securitized Western aid policies, the concepts of increasing aid, faltering democracy and an intensified anti-terrorist stance become easily connected dots in a web of implicit aid conditionality. Although Uganda’s democratization process has regressed in the past decade, an increase in foreign aid has simultaneously occurred. This disengagement of democracy and development aid is counterintuitive when looking at the Western world’s explicit good governance conditionality framework. In light of Uganda’s strategic position in the Horn of Africa and unwavering consistency in its support for the War on Terror, it therefore becomes legitimate to draw a more implicit conditionality link between increasing aid – from the two most visible War on Terror allies no less – to Uganda’s supportive War on Terror behaviour.

Conclusion

The increased securitization of development issues and its effect on Western World discourse and aid policies have served to undermine African democracy in multiple and overlapping ways. As oppressive anti-terror legislation impinges on African human rights by enabling the persecution and marginalization of certain groups, an implicit War on Terror aid conditionality indirectly impinges on African political rights by undermining the explicit aid goal of democratization.

As Fritz and Menocal (2007) note,

“aid, and the various modalities through which it is provided can generate negative or perverse incentives and unintended consequences for the development of capable, well governed, effective and accountable states” (p. 542).

The growing securitization of development issues and its influence on aid have unfortunately caused many African states to become examples of this fate. How, therefore, can this trend be reversed or counteracted in the future to cultivate democracy and advance human freedoms in the developing world?

Looking externally, geopolitical trends may offer hope as China becomes an increasingly critical player in delivering foreign aid to Africa (Aning, 2010). Although stability will most likely remain an important condition for receiving funding, China will likely offer much less political interference in its aid conditionality framework (Vines, 2007). This could be viewed negatively in that it would allow African leaders to completely regress towards their countries’ previously authoritarian regimes. On the other hand, it may also allow for true ownership in the democratization process, which has arguably been the missing piece in building truly accountable democratic regimes. The Arab Spring offers a hopeful example for this internally-generated democratization process, and may serve to motivate and inspire African neighbours.

Whether the democratization process is guided from without or generated from within, Bush’s heavy words quoted at the beginning of this paper – and the acute increase in securitization they provoked – need to be revisited and somehow extracted from development discourse. If not, development aid will continue to be hijacked by the imperatives of the War on Terror and, as a result, remain out of reach for many countries that need it most.

References

Abrahamsen, R. (2000). Economic liberalization and democratic erosion. In Disciplining democracy (p. 112-137). London UK; New York, NY: Zed Books.

Abrahamsen, R. (2005). Blair’s Africa: The politics of securitization and fear. Alternatives, 30: p. 55-80.

Adetula, V. A. (2011). Measuring democracy and ‘good governance’ in Africa: A critique of assumptions and methods. In K. Kondlo & C. Ejiogu (Eds.), Governance in the 21st century (p. 10-25). Capetown, SA: Human Sciences Research Council.

Aning, K. (2010). Security, the War on Terror, and official development assistance. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 3 (1): p. 7-26.

Barnett, M., & Duvall, R. (2005). Power in international politics. International Organization, 59(1): 39-75.

Callaghy, T. M. (2001). Networks and governance in Africa: Innovation in the debt regime. In T. Callaghy, R. Kassimir, & R. Latham (Eds), Intervention and transnationalism in Africa: Global-local networks of power (p. 115-148). Cambridge, UK; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Cammack, D. et al. (2006). Donors and the ‘Fragile States’ agenda: A survey of current thinking and practice. London, UK: Poverty and Public Policy Group & Overseas Development Institute.

Cammack, P. (2004). What the World Bank means by poverty reduction, and why it matters. New Political Economy, 9(2): 189-211.

Carmody, P. (2005). Transforming globalization and security: Africa and America Post-9/11. Africa Today, 52 (1): p. 97-120.

Cooper, N. (2005). Picking up the pieces of the liberal peaces: Representations of conflict economies and the implications for policy. Security Dialogue, 36 (4): p. 463-478.

Duffield, M. (2010). The liberal way of development and the development-security impasse: Exploring the global life-chance divide. Security Dialogue, 41 (1): p. 53-76.

Fisher, J. (2012). Managing donor perceptions: Contextualizing Uganda’s 2007 intervention in Somalia. African Affairs, 111 (444): p. 404-423.

Fritz, V. & Menocal, A. R. (2007). Developmental states in the new millennium: Concepts and challenges for a new aid agenda. Development Policy Review, 25 (5): p. 531-552.

Fukuda-Parr, S. et al. (2002). Human development report 2002: Deepening democracy in a fragmented world. New York, NY; Oxford, UK: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Furley, O. (1999). Democratisation in Uganda. Warwickshire, UK: The Research Institute for the Study of Conflict and Terrorism.

Harmer, A. & Macrae, J. (Eds.). (2004). Beyond the continuum: The changing role of aid policy in protracted crises. Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved from: http://www.odi.org.uk/resources/docs/279.pdf

Hettne, B. (2010). Development and security: Origins and future. Security Dialogue, 41 (1): p. 31-52.

Keane, J. et al. (2010). Uganda: Case study for the MDG gap task force report. Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved from: http://www.un.org/esa/policy/mdggap/mdggap2010/mdggap_uganda_casestudy.pdf

Knack, S. (2004). Does foreign aid promote democracy? International Studies Quarterly, 48: p. 251-266.

Lynch, G. & Crawford, G. (2011). Democratization in Africa 1990-2010: An assessment. Democratization, 18 (2): p. 275-310.

Mwenda, A. M. (2007). Personalizing power in Uganda. Journal of Democracy, 18 (3): p. 23-37.

Newman, E. (2009). Failed states and international order: Constructing a post-westphalian world. Contemporary Security Policy, 30 (3): p. 421-443.

Osman, A. A. (2008). Democracy and governance in Africa: Complimentary or controversial? In L. Moshi & A. Osman (Eds.), Democracy and culture: An African perspective (p. 127-143). London, UK: Adonis & Abbey Publishers Ltd.

Prestholdt, J. (2011). Kenya, the United States, and Counterterrorism. Africa Today, 57 (4): p. 2-27.

Sande Lie, J. H. (2010). Developmentality and the World Bank in the New Aid Architecture. In J. McNeish and J. Sande Lie, Security and Development (p. 36-51). New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

Ssewanyana, S. et al. (2011). Building on growth in Uganda. In P. Chuhan-Pole & M. Angwafo, Yes Africa can: Success stories from a dynamic continent (p. 51-64). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Tangri, R. & Mwenda, A. M. (2010). President Museveni and the politics of presidencial tenure in Uganda. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 28 (1): p. 31-49.

Vines, A. (2007). China in Africa: A Mixed Blessing? Current History. 106 (700): 213-219

Williams, P. D. (2008). Regional arrangements and transnational security challenges: The African Union and the limits of securitization theory. African Security, 1: p. 2-23.

World dataBank. (2012, April 16). World Development Indicators [Data file created based on Uganda selected as the country, Net official development assistance and official aid received (constant 2009 US$) and Net bilateral aid flows from DAC donors, United States (current US$) selected as the indictors, and 1990 to 2011 selected as the time frame]. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators?cid=GPD_WDI.

—

Written by: Kathryn Brunton

Written at: University of Ottawa

Written for: Rita Abrahamsen

Date written: April 2012

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- A Well-Intentioned Curse? Securitization, Climate Governance and Its Way Forward

- Neo and the ‘Hacker Paradox’: A Discussion on the Securitization of Cyberspace

- Drones, Aid and Education: The Three Ways to Counter Terrorism

- The Securitization of Christianity under Xi Jinping

- Horizontal Partnership for Gender-responsive Localisation of Humanitarian Aid

- Prestige Aid: The Case of Turkey