‘Military intervention is more likely to backfire and hurt the intervening state than to provide a satisfactory solution to problems in the target state’.

There are several forms of military intervention: regime change, ‘humanitarian’ intervention, and peacekeeping, amongst others. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union (1991), the number of military interventions doubled[1] under the auspicious of upholding human rights, otherwise known as ‘humanitarian’ interventions. Scholars such as Kenneth Waltz, claim that this is due to the United States’ (U.S.) hegemonic role in the ‘new world order’[2]. As a result, U.S. liberal values of freedom, democracy and free markets, favoured[3] notions of ‘natural law’, such as human rights, over state sovereignty and other norms of ‘positive law’. However, following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, U.S. military interventions changed to reflect a new foreign policy directed by national and international security concerns under the ‘War on Terror’ rhetoric. As such, this paper shall scrutinise various U.S. military interventions, under the basis of humanitarian and security purposes since the end of the cold war. It will do so in order to demonstrate how military interventions are always liable to backfire and cause unintended harm to an intervening state on various grounds, such as ideological, political and economic harm, than it is in providing a ‘satisfactory’ solution to problems in a target state. The paper shall enforce this stance through the analysis of real time examples of U.S. military interventions such as, Kosovo (1998-99) and Iraq (2003).

Initially, before such a discussion can begin, one must have a clear interpretation as to what constitutes as a ‘satisfactory’ solution. Naturally, the definition varies on the nature of each problem. This is due to the justifications of each military engagement differing on a case-by-case basis and thus, the methods of engagement and subsequently the end result differing also. For the purpose of the reader, this paper shall abide to Jeff Holzegrefe’s definition of a humanitarian intervention’s ‘satisfactory’ solution to a crisis as: “the use of force, across state borders by a state (or group of states), which seeks to prevent or end widespread grave violations of fundamental human rights”[4]. In addition, so to better understand and analyse whether a ‘satisfactory’ solution has been achieved, the outcomes of a ‘humanitarian’ intervention must be divided upon short-term and long-term results. Equally, it is important to understand what constitutes as harm to an intervening state. Thus, the meaning of harm is regarded as any, direct or indirect, consequence(s) which causes negative impacts on an intervening state as a result of its military engagement in a target state.

Perhaps, the most controversial ‘humanitarian’ intervention is the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s (NATO) engagement during the Kosovo conflict. The intervention was conducted in defence of Kosovo’s Albanian population amidst Yugoslav state sponsored ethnic violence and in order to maintain regional stability. Eventually, the intervention forced an end to the violence under the Kumanovo Agreement (1999) and therefore leading one to presume the U.S., which led the intervention, achieved a ‘satisfactory’ solution to the problem in Kosovo. This seems to be the case, at least in terms of providing a short-term ‘satisfactory’ solution, as the intervention forced an end to the violence and thus, satisfying Holzegrefe’s definition of ending widespread human rights violations. Also, Holzegrefe’s focus on the use of force across borders is also fulfilled as NATO’s use of air-strike forced the withdrawal of Yugoslav forces from Kosovo and the immediate cessation of violence.

Conversely, according to scholars such as Noam Chomsky, the intervention achieved the contrary instead intensifying the atrocities[5]. The intensification of crimes was a direct consequence of foreign intervention, as it contributed to the war’s pretence of lawlessness which enabled mass human rights violations to go unchecked. This is evidenced by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, which reported an increase[6] of civilian executions and refugee influx into neighbouring states immediately following the commencement of the U.S. led intervention. Additionally, following the war’s conclusion, an open campaign of reverse ethnic-cleansing saw the mass evacuation[7] of Serbs from Kosovo, to which NATO forces remained paralyzed in preventing. Therefore, the intervention failed provide a short-term ‘satisfactory’ solution to the human rights abuses, as the escalation of violence during the intervention and after, were both the result of foreign intervention. Furthermore, the U.S.A’s role in Kosovo became synonymous with pan-Albanianism[8] as, its support for the Kosovo Liberation Army contributed to the Albanian-led secessionist conflicts in Serbia (2000) and Macedonia (2001), which threatened to destabilize[9] the entire Balkans.

Conversely, the U.S.A faced a further multitude of ramifications which harmed it in numerous ways, particularly within the ideological dimension amongst the international community. This was especially the case within the Third World, with many states, primarily Russia which holds territorial integrity as a barrier from Western invasion[10], fearing a similar intervention on their soil. Such fears were the result of the U.S.A’s disregard for international law, as it refused to gain explicit United Nations (UN) approval. In turn, this harmed the U.S.A’s international image as the defender of democracy[11] which it had achieved during the liberation of Kuwait (1991). As such, this led to several accusations against the U.S. as perpetrating a new imperialist agenda, attempting to pursue self-interests under the exploits of the ‘Washington Consensus’, while masquerading in defence of human rights[12], with Yugoslavia being the chosen experiment. Certain scholars have equated the U.S. to former European colonialist powers[13] during the 19th century which pursued national interests at the expense of other states, under the compass of ‘delivering civilization’ to the indigenous peoples of Africa as part of the ‘Whiteman’s burden’. Therefore, the U.S.A’s involvement in Kosovo backfired and caused the U.S. harm, as it diminished its international image as a moral leader, with one specific writer accusing the U.S. of being a “rogue superpower”[14].

Additionally, perceptions of U.S. imperialism, in conjunction with the dismissal of international law and the UN, also caused the U.S. political harm. Mainly, the intervention fractured U.S.-Russo relations. Existing Russian sentiments towards NATO’s presence in a post-cold war era, alongside strong economic turmoil, increased Russian fears of an imminent U.S. invasion[15] as a result of its new orientation towards defending human rights. These fears were further antagonised amid growing human rights concerns as Russia battled with Muslim separatists during the Second Chechen War (1999-2009). Furthermore, the refusal to incorporate Russian military capabilities into the Kosovo conflict harmed the U.S. as the disregard for a multilateral intervention with non-NATO members, in a conflict which was of greater geostrategic importance to Russia than it was to the U.S., signified a microcosm of future U.S. hegemony in the international system. Consequently, the fear of being victim to future U.S. hegemonic influence was demonstrated by the creation of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (2011), to which Hessbruegge suggests as a clear response[16] to the U.S.A’s role in Kosovo.

Theoretical arguments surrounding NATO’s intervention in Kosovo are also extremely divided. Classical-liberals argue that grievances, such as human rights, within a pluralist society must be settled domestically. This is asserted by liberal philosopher James Stuart Mill who argues the enforcement of human rights by outside forces (interventions), cannot hold[17] legitimacy in the long-term as only domestic populations can decide as to what suffices as a ‘satisfactory’ solution to their problems. Writing in 1869, Mill’s perspective is exemplified by contemporary socio-ethnic issues in Kosovo, as witnessed during the mass riots of 2004 which exposed the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo’s (UNMIK) inability to prevent the mass violence that followed. Therefore, this underlines the intervention’s inability, at least in accordance to Holzegrefe’s definition, in providing a long-term ‘satisfactory’ solution to the problems in Kosovo, as ethnic violence did not cease to exist in 1999. On the contrary, cosmopolitans prescribe a notion of human commonality which holds the defence of human rights as a duty for all states to uphold[18]. Thus, as part of NATO, the U.S. led intervention, in accordance to Holzegrefe’s definition, is considered as a ‘satisfactory’ solution to the problems in Kosovo, as the human rights violations of the Kosovar Albanians were ultimately alleviated by a collective (U.S. led) NATO force.

Meanwhile, neo-realists stipulate that states continuously pursue national interests in order to optimize their absolute gains and as such states are unwilling to risk their military for purely ‘humanitarian’ reasons. Naturally, this rejects the Clinton Doctrine’s portrayal of the U.S.A’s new fixation in upholding human rights as a purely moral obligation. This is evidenced when addressing NATO’s method of intervention in Kosovo: air-strikes only. This seems to suggest that the lives of NATO forces (U.S. pilots), were of more importance than the lives of the Kosovar Albanians to who’s persecution the intervention was justified on. As such, this has ignited the debate of selective engagement, an argument which seems to hold weight when one examines the U.S.A’s disregard to intervene in much larger humanitarian crises at the same time as Kosovo, such as Darfur. Yet, complete inaction itself can also harm a state as it did to the U.S. in its refusal to intervene during the Rwandan genocide (1994). Ironically, this neo-realist perspective was exemplified by the eventual French intervention in Rwanda, to which Destexhe has accused France of only intervening in order to deter growing Anglo-American influences in the predominantly French speaking state[19]. Thus, the neo-realist paradigm suggests that military interventions are more likely to backfire and harm the intervening state as they are accused of pursuing national interests, rather than seeking to prevent human rights violations.

Kosovo aside, since 9/11, U.S. military interventions have been less focused on defending human rights and more on deterring national and international security threats, particularly, fundamental Islamism. In turn, this has resulted into a barrage of contested military interventions, with Iraq (2003), being the centre of focus for many scholars. Unlike ‘humanitarian’ interventions, when examining whether or not the U.S. has provided a ‘satisfactory’ solution to the problems Iraq, the definition is different. Thus, the remainder of the paper will adhere to Robert Jacksons’ definition of a ‘satisfactory’ solution to a security concern as: the defeat/deterrence of any foreign dangers and menaces from threat, intervention, invasion, destruction, occupation or some other harmful interference by a hostile foreign power or terrorist group[20]. Yet the definition of harm remains almost identical, with the only difference being the prospect that certain harms can disrupt national security.

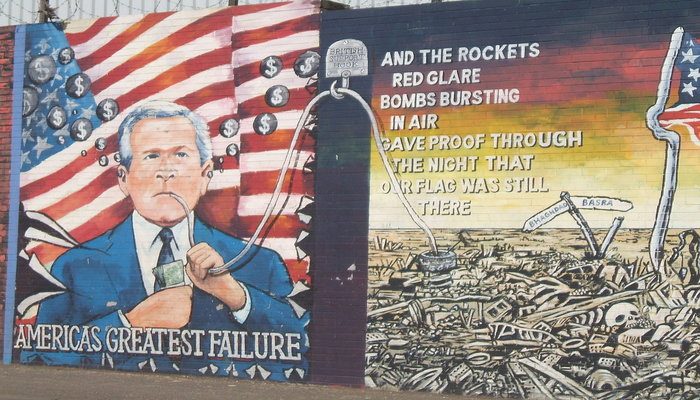

Initially, the U.S. intervention in Iraq was conducted under the rhetoric of disrupting Saddam Hussein’s Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMDs) ‘programme’, which the George W. Bush administration posed as constituting a threat to U.S. national security as Hussein allegedly had links[21] to al-Qaeda. However, U.S. forces were unable to retrieve any evidence of Hussein’s WMDs ‘programme’. Immediately, one is able to identify that the U.S.’s intervention backfired and caused more harm than it did in providing a ‘satisfactory’ solution as the intervention was conducted on the premise of finding WMDS, which evidently did not exist. Moreover, according to one particular writer, Rick Fawn, there is no evidence of al-Qaeda presence in Iraq prior to the U.S. intervention, therefore refuting the Bush administration’s claims of Hussein having links to terrorist networks. In fact, Fawn elaborates by suggesting that the U.S. invasion was a direct catalyst in Iraqi support for al-Qaeda. This is due to Hussein’s capitulation[22] enabling al-Qaeda to exploit religious differences within Iraq which had previously been suppressed under dictatorial rule. So, this suggests the U.S. intervention not only failed in providing a ‘satisfactory’ solution to the security issues in Iraq, it in fact contributed to the rise of Islamic extremism in the country.

Extensively, following the failure to allocate WMDs, the U.S. continued to defend the intervention under the provisions of implementing democracy in the Middle-East. The rhetoric of democratisation followed the assumption that once democracy had been established in Iraq it would spread to neighbouring states hostile towards the U.S. (Iran), therefore destroying the need for Islamic terrorism. However, on 1st October 2003, the U.S. imposed Ayad Allawi, a prominent Shi’a politician as the new Iraqi Prime minister. The imposition of Allawi backfired on the U.S. with dire consequences. Politically, the installation of a Shi’a head of state strengthened Iran’s regional influence as it granted Iran an ally which it had previously not enjoyed[23]. An increase in Iranian influence within the Middle-East has strongly harmed the U.S.A’s presence within the region, as is the case with the ongoing Syrian civil-war (2011-), whereby U.S. attempts to overthrow the Assad regime is strongly diminished by Iranian (and Russian) support for pro-government forces.

Furthermore, the U.S.A’s empowerment of Iraqi Shiite’s has not, even at the time of writing this paper, been successful in orchestrating a sufficient political process[24]. Rather, it has contributed to its fracture by fostering sectarian violence. Evidently, this was exemplified during the mass sectarian violence[25] which engulfed all aspects of Iraqi life from 2006 to 2007 and continues to do so with the current conflict against ISIS. Therefore, although the sectarian violence is a civil issue, the creation of widespread violence is attributed to the U.S.A’s intervention. Constant conflict has led to the imposition of various draconian-style laws, hazardous environment and extreme living conditions which have disenfranchised a strong proportion of Muslims, not just in Iraq but the entire region also. As a result, it is understandable that the rise in sectarian violence is attributed to coercive military intervention which continues to stretch the gap between the population and the state[26]. In return, this has significantly harmed the U.S. ideologically, as it has gained a reputation as an anti-Islamic force intervening for the purpose to securing Iraq’s oil supplies. As a result, this has fuelled international Islamic extremism[27], which is conducted in retaliation for U.S. involvement in Iraq, such as the London underground bombings (2005). Therefore, the U.S. intervention in Iraq vindicates that military interventions are more likely to backfire and harm the intervening state than to provide a ‘satisfactory’ solution in a target state, as the U.S. intervention in Iraq strengthened international terrorism on the assumption that the U.S. was anti-Islamic.

Lastly, the intervention has also posed enormous economic harm upon the U.S., as the cost of the intervention alone is more than $2 trillion[28]. As a result, the U.S. economy has suffered, with an unemployment rate above 10% (2009). More so, the increase of non-state terrorism has pervasively fuelled the militarisation of states, particularly the U.S., which had previously been initiated during the cold war[29].This is clearly evidenced by the U.S.A’s military expenditure that compromised 4.75%[30] of the total U.S. GDP (2011). Furthermore the U.S.A’s withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 has left a weak security structure behind that has enabled extremist groups, such as ISIS, to control vast amounts of territory which in turn requires further U.S. economic (and military) support in order to restore security. Thus, according to Robertson’s definition, the U.S. intervention in Iraq has again failed to provide a ‘satisfactory’ solution to the security issues in Iraq and as the economic consequences of the intervention have exemplified, the intervention caused more harm for the U.S. than it did in providing a ‘satisfactory’ solution to the problems in Iraq.

In conclusion, military interventions always backfire as they are liable to create or even be subject to harmful consequences, as the U.S. has been to Islamic extremism as a result of its intervention in Iraq. Theoretically, at least in respect to ‘humanitarian’ interventions, classical-liberalists hold this to be evident as foreign interventions cannot provide ‘satisfactory’ solutions to another state’s problem and thus further issues are therefore created. Partially, this is due to foreign interventions being viewed as a new method of 21st century colonialism. Meanwhile, neo-realists claim, due to the increasingly hostile international system in the ‘new world order’, states (especially the U.S. as the world’s hegemonic power) constantly seek to ensure their national interests through humanitarian interventions, rather than seeking to provide an actual ‘satisfactory’ solution to problems in a target state. This seems to be the case when one addresses the inaction of the U.S. to intervene in humanitarian situations which hold no national interests, such as Darfur and Rwanda. Meanwhile, according to cosmopolitans, the duty to uphold human rights is a universal principle and thus inaction itself is able to harm a state. Yet, the idea of intervening militarily in order to uphold human rights is a notion in itself which suggests that military interventions are liable to backfire and harm a state[31], than it is in providing a ‘satisfactory’ solution to problems in a target state, as further suffering is caused.

Bibliography

Antonenko, Oksana. “Russia, NATO and European Security after Kosovo”, (Survival), (Vol. 41, No. 4), (1999), pp. 124-144.

Ayoob, Mohammed. “Defining security: a subaltern realist perspective”, (Critical security studies), (1997), p. 121-146.

Bacevich, Andrews J. American Empire: The Realities & Consequences of U.S. Diplomacy, (Harvard University Press, Massachusetts, USA), (2002).

Bilmes, Linda and Joseph Stiglitz. “The economic costs of the Iraq war: An appraisal three years after the beginning of the conflict. (No. 12054), (National Bureau of Economic Research), (2006), p. 1-38.

Borton, John. “An Account of Co-ordination Mechanisms for Humanitarian Assistance During the International Response to the 1994 Crisis in Rwanda”, (Disasters), (Vol. 20, No. 4), (1996), pp. 305-323.

CIA, The World Factbook: Military expenditures”, (2015), https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2034.html.

Chomsky, Noam. Failed States: The Abuse of Power and The Assault on Democracy, (Hamish Hamilton, London, UK), (2006).

Chomsky, Noam. The New Military Humanism: Lessons from Kosovo, (Pluto Press, London, UK), (1999).

Chinkin, Christine M. “Kosovo: a “good” or “bad” war?”, (American Journal of International Law, (1999), p. 841-847.

Cohen, Warren I. America’s Failing Empire: U.S. Foreign Relations since the Cold War, (Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK), (2005).

Combs, Jerald D. The History of American Foreign Policy, Volume II, Since 1900, (San Francisco University, Newbery Award Records, Inc.), (1986).

Daalder, Ivo H. “Emerging answers: Kosovo, NATO, & the use of force”, (The Brookings Review, Vol. 17, No. 3), (1999), pp. 22-25.

Davidson, Joana. “Humanitarian Intervention as Liberal Imperialism: A Force for Good”, (POLIS Journal), (Vol. 7), pp. 128-164.

Destexhe, Alan. Rwanda and Genocide in the Twentieth Century, (Pluto Press, London, UK), (1995).

Duffield, Mark. Development, Security and Unending War: Governing the World of Peoples, (Polity Press, Cambridge, UK), (2007).

Eland, Ivan. “U.S. Intervention Backfires”, (Independent Institute), (2003), http://www.independent.org/newsroom/article.asp?id=1182

El-Shibiny, Mohamed. Iraq: A Lost War, (Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke), (2010).

El-Shibiny, Mohamed. The Threat of Globalization to Arab Islamic culture: The Dynamics of World Peace, (Dorrance Publishing, Pittsburgh, USA), (2005).

Falk, Richard A. “Kosovo, world order, and the future of international law”, (American Journal of International Law), (1999), pp. 847-857.

Finnemore, Martha. The Purpose of Intervention: Changing beliefs about the use of force, (Cornell University Press, London, UK), (2003).

Gershkoff, Amy and Shana Kushner. “Shaping public opinion: The 9/11-Iraq connection in the Bush administration’s rhetoric”, (Perspectives on Politics), (Vol. 3, No. 3), (2005), p. 525-537.

Haass, Richard N. Intervention: The Use of American Military Force in the Post-Cold War Word, (Brookings Institute Press, Washington D.C., USA), (1999).

Held, David & Anthony McGrew. The Global Transformations Read: An Introduction to the Globalization Debate, (Polity Press, Cambridge, UK), (Second Edition), (2003).

Hehir, Aiden. Humanitarian Intervention: An Introduction,(Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke), (2013).

Herring, Eric and Glen Rangwala. Iraq in Fragments: The Occupation and its Legacy, (Hurst & Company, London, UK), (2006).

Hessebruegge, Jan Arno. “The Shanghai Cooperation Organization: A Holy Alliance For Central Asia? (The Fletcher School Online Journal for Issues related to Southwest Asia and Islamic Civilization), (2004), p. 1-9

Hineebusch, Raymond. “The Iraq War and International Relations: Implications for Small States”, (Cambridge Review of International Affairs), (Vol. 19, No. 3), (2006), pp. 451-463.

Hippel, Karin von. Democracy by Force: US Military Intervention in the Post-Cold War World, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK), (2000).

Holzgrefe, J. L and Robert O Keohane. Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical, Legal and Political Dilemmas, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge), (Sixth Edition), (2008).

Huntington, Samuel P. “The lonely superpower”, (Revenue Internationale Et Strategique), (1999), pp. 18-28.

Ignatieff, Michael. “Empire Lite: Nation-Building in Bosnia, Kosovo and Afghanistan”, (Vintage), (2003).

Jackson, Robert. The Global Covenant: Human Conduct in a World of States, (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK), (2003).

Kagan, Frederick W., Kimberly Kagan and Danielle Pletka. “Iranian influence in the Levant, Iraq, and Afganisation”, (A report of the American Enterprise Institute), (2008), p. 37-57.

Kaufmann, Chaim. “Possible and Impossible Solutions to Ethnic Civil Wars”, (International Security), (Vol. 20, No. 4), (1996), pp. 136-175.

Ku, Charlotte and Harold K. Jacobson. Democratic accountability and the use of force in international law, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK), (2005).

MacQueen, Norrie. Humanitarian Intervention and the United Nations, (EUP Publishing, Chippenham and Eastbourne), (2011).

Mamdani, Mahmood. Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: America, The Cold War, and the Roots of Terror, (Pantheon Books, New York, USA), (2004).

Melanson, Richard A. “American Foreign Policy Since The Vietnam War: The Search for Consensus from Richard Nixon to George W. Bush”, (M.E. Sharpe, Inc., Fourth Edition), (2005).

Mill, John Stuate. On Liberty, (Longmans Green, Reader and Dyer, London, UK), (Fourth Edition), (1869).

Nordhaus, William D. The Economic Consequences of a War with Iraq, (National Bureau of Economic Research), (No. w9361), (2002).

Norris, John. Collision Course: NATO, Russia and Kosovo. (Praeger Publishers, Connecticut, USA), (2005).

Parenti, Michael. Against Empire, (City Lights Books, San Francisco, USA), (1995).

Sangha, Karina. “The Responsibility to Protect: A Cosmopolitan Argument for the Duty of Humanitarian Intervention (University of Victoria), (2012), p. 3-13

Shaw, Martin. “Global society and international relations”, (1994).

Teson, Fernando. “Kosovo: A Powerful Precedent for the Doctrine of Humanitarian Intervention”, (Amsterdam Law Forum), (Vol. 1, No. 2), (2009), pp. 42-48.

United Nations, United Nations Refugee Agency, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Executive Committee for the High Commissioner’s, Standing Committee. “The Kosovo Refugee Crisis: An Independent Evaluation of UNHCR’s Emergency Preparedness and Response”, (2000), http://www.unhcr.org/3ae68d19c.html

Waltz, Kenneth. “Structural realism after the Cold War”, (International Security), (Vol. 25, No. 1), pp. 5-41.

Waltz, Kenneth. Theory of International Politics, (Waveland Press Inc., Illinois, USA), (2010).

Wheeler, Nicholas J. “Reflections on the Legality and Legitimacy of NATO’s Intervention in Kosovo”, (The International Journal of Human Rights), (Vol. 4, No. 3-4), (2000), pp. 144-163.

Wenger, Andreas & Doron Zimmermann. International Relations: From the Cold War to the Globalized World, (Lynne Reiner Publishers, London, UK), (2003).

Endnotes

[1] Ku, Charlotte and Harold K. Jacobson. Democratic accountability and the use of force in international law, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK), (2005), p. 17

[2] Waltz, Kenneth. “Structural realism after the Cold War”, (International Security), (Vol. 25, No. 1), p. 38

[3] Duffield, Mark. Development, Security and Unending War: Governing the World of Peoples, (Polity Press, Cambridge, UK), (2007), p. 121

[4] Holzegrefe, Jeff L. and Robert O Keohane. Humanitarian intervention: ethical, legal and political dilemmas, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge), (Sixth Edition), (2008), p. 18

[5] Chomsky, Noam. The New Military Humanism: Lessons from Kosovo, (Pluto Press, London, UK), (1999), p. 150

[6] United Nations, United Nations Refugee Agency, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Executive Committee for the High Commissioner’s, Standing Committee. “The Kosovo Refugee Crisis: An Independent Evaluation of UNHCR’s Emergency Preparedness and Response”, (2000), http://www.unhcr.org/3ae68d19c.html

[7] Falk, Richard A. “Kosovo, world order, and the future of international law”, (American Journal of International Law), (1999), p. 852

[8] Antonenko, Oksana. “Russia, NATO and European Security after Kosovo”, (Survival), (Vol. 41, No. 4), (1999), p. 131

[9] Norris, John. Collision Course: NATO, Russia and Kosovo. (Praeger Publishers, Connecticut, USA), (2005), p. 41

[10] Ayoob, Mohammed. “Defining security: a subaltern realist perspective”, (Critical security studies), (1997), p. 139

[11] Wenger, Andreas & Doron Zimmermann. International Relations: From the Cold War to the Globalized World, (Lynne Reiner Publishers, London, UK), (2003), p. 334

[12] Chomsky, Noam. The New Military Humanism: Lessons from Kosovo, (Pluto Press, London, Uk), (1999), p. 103

[13] Chomsky, Noam. The New Military Humanism: Lessons from Kosovo, (Pluto Press, London, UK), (1999), p. 141

[14] Huntington, Samuel P. “The lonely superpower”, (Revenue Internationale Et Strategique), (1999), p. 23

[15] Jackson, Robert. The Global Covenant: Human Conduct in a World of States, (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK), (2003), p. 283

[16] Hessebruegge, Jan Arno. “The Shanghai Cooperation Organization: A Holy Alliance For Central Asia? (The Fletcher School Online Journal for Issues related to Southwest Asia and Islamic Civilization), (2004), p. 3

[17] Mill, John Stuart. On Liberty, (Longmans Green, Reader and Dyer, London, UK), (Fourth Edition), (1869), p. 73

[18] Sangha, Karina. “The Responsibility to Protect: A Cosmopolitan Argument for the Duty of Humanitarian Intervention (University of Victoria), (2012), p. 3

[19] Destexhe, Alan. Rwanda and Genocide in the Twentieth Century, (Pluto Press, London, UK), (1995), p. 52

[20] Jackson, Robert. The Global Covenant: Human Conduct in a World of States, (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK), (2003), p. 187

[21] Gershkoff, Amy and Shana Kushner. “Shaping public opinion: The 9/11-Iraq connection in the Bush administration’s rhetoric”, (Perspectives on Politics), (Vol. 3, No. 3), (2005), p. 525

[22] Fawn, Rick and Raymond Hinnebusch. The Iraq War: Causes and consequences, (Lynne Reinner Publishers, London, UK), (2006), p. 244

[23] Kagan, Frederick W., Kimberly Kagan and Danielle Pletka. “Iranian influence in the Levant, Iraq, and Afganisation”, (A report of the American Enterprise Institute), (2008), p. 37

[24] Herring, Eric and Glen Rangwala. Iraq in Fragments: The Occupation and its Legacy, (Hurst & Company, London, UK), (2006), p. 163

[25] Fawn, Rick and Raymond Hinnebusch. The Iraq War: Causes and consequences, (Lynne Reinner Publishers, London, UK), (2006), p. 214

[26] Herring, Eric and Glen Rangwala. Iraq in Fragments: The Occupation and its Legacy, (Hurst & Company, London, UK), (2006), p. 163

[27] Hineebusch, Raymond. “The Iraq War and International Relations: Implications for Small States”, (Cambridge Review of International Affairs), (Vol. 19, No. 3), (2006), p. 457

[28] Bilmes, Linda and Joseph Stiglitz. “The economic costs of the Iraq war: An appraisal three years after the beginning of the conflict. (No. 12054), (National Bureau of Economic Research), (2006), p. 2

[29] Shaw, Martin. “Global society and international relations”, (1994), p. 146

[30] CIA, The World Factbook: Military expenditures”, (2015), https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2034.html

[31] Chinkin, Christine M. “Kosovo: a “good” or “bad” war?”, (American Journal of International Law, (1999), p. 843

Written by: Flamur Krasniqi

Written at: Brunel University, London

Written for: John MacMillan

Date Written: February 2016

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Third Pillar: The Vulnerable Component of the ‘Responsibility to Protect’

- Are Non-democracies More Susceptible to Coups than Democracies in West Africa?

- Private Military Companies and Sacrifice: Reshaping State Sovereignty

- Critics of Liberal Peace: Are Hybridity & Local Turn Approaches More Effective?

- Brexit and Beyond: How Security Threats are Constructed

- Are ‘Climate Refugees’ Compatible with the 1951 Refugee Convention?