This is an excerpt from Sexuality and Translation in World Politics. Get your free copy here.

Sexual diversity has historically been the norm, not the exception, among Indigenous peoples. Ancestral tongues prove it. In Juchitán, Mexico, muxes are neither man nor woman, but a Zapotec gender hybridity. In Hawai’i, the māhū embrace both the feminine and masculine. The Māori term takatāpui describes same-sex intimate friendships, and since the 1980s it is the term used alongside the term queer. Non-monogamy is the norm among the Zo’é peoples in Amazonia and in the Ladakhis in the Himalayas. In other words, Indigenous sexualities were never straight: ranging from cross-dressing to homo-affective families, they are as diverse as the peoples who practice them. But if native terminologies referring to same-sex practices and non-binary, fluid understandings of gender existed before the emergence of LGBT frameworks, why are indigenous experiences invisible in international sexual rights debates? Language shows that Indigenous queerness, in its own contextual realities, predates the global LGBT framework. Yet Indigenous experiences are rarely perceived as a locus of sexual diversity. This is partly because Indigenous peoples are imagined as remnants of the past, whereas sexual diversity is associated with political modernity. In Indians in Unexpected Places, Phillip Deloria (2004) explored cultural expectations that branded Indigenous peoples as having missed out on modernity. Sexual freedoms, in turn, are associated with global human rights, secular modernity, and Western cosmopolitanism (Rahman 2014; Scott 2018). Indigenous homosexualities provoke chuckles because they disrupt expectations of modernity. They surprise because they express sexual diversity in non-modern places.

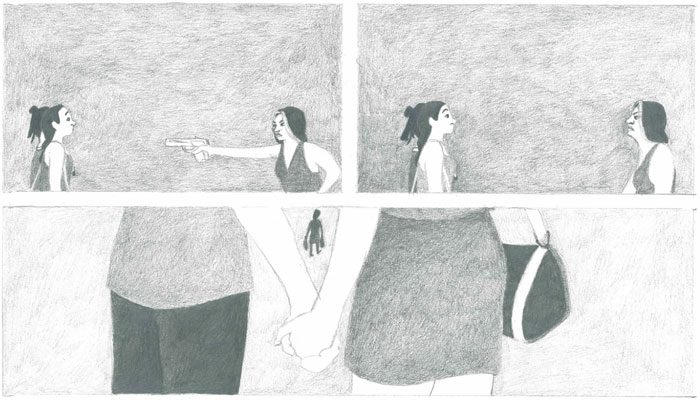

Indigenous queerness is also invisible because sexual terminologies are lost in translation. The meanings of gender roles and sexual practices are cultural constructions that inevitably get lost when they are decontextualised in cultural (and linguistic) translation. The spectrum of Indigenous sexualities does not fit the confined Western registries of gender binaries, heterosexuality, or LGBT codification. It is not these idioms that are untranslatable, but rather the cultural and political fabric they represent. Indigenous sexualities defy contemporary LGBT and queer frameworks.

Queer debates do not travel well, whether in space or in time. The idea that a person is homosexual, for instance, stems from contemporary assumptions of sexual identity and is only possible after the invention of homosexuality (Katz 2007). Mark Rifkin (2011) asks when Indian became straight because heterosexual vocabulary is as inappropriate to understand Indigenous worldviews as the binary imagination. The problem is not only that the global sexual rights regime cannot account for the place of desire in pre-colonial societies; it is also that discussions of Indigenous sexualities in English risk being anachronistic and misrepresentative. Indigenous sexualities are embedded in the impossibilities of epistemological translation.

This chapter sheds light on the value of Indigenous diversities for non-Indigenous worlds. There are an estimated 370 million Indigenous persons in 90 countries; over 5000 nations that speak thousands of languages. Indigenous peoples are as diverse as the processes of colonisation they continue to endure. There are many terms to refer to them – Indian, Native, First Nations, Indigenous, and Tribal peoples – because their experiences relate to a plurality of power relations that vary across colonial experiences.[1] The term ‘Indian’ was invented by colonial governments to subordinate vastly distinct peoples in a homogenising legal status (Van Deusen 2015). Indigenousness is a political identity. It refers less to a constitutive who/what than to the otherness implied by it. Mohawk and Cherokee scholars Taiaiake Alfred and Jeff Corntassel (2005) define being Indigenous today as an oppositional identity linked to the consciousness of struggle against ongoing forms of dispossession and assimilation by subtler forms of colonialism that spread out of Europe. This includes sexual colonisation. As colonial powers appropriated Indigenous territories, they tried to control, repress and erase Indigenous sexualities. Colonisation regulated Indigenous gender experiences, supplanting them with Western sexual codes associated with (Christian) modernity. Scholars exposed the heteronormativity of colonialism (Smith 2010), insisted on the value to decolonise queer studies and queer decolonial studies (Driskill et al. 2011; Morgensen 2011). We contribute a linguistic perspective to this debate.

Indigenous sexualities resist translation as much as they resist erasure. This essay first looks at the vast diversity of Indigenous sexualities across time and borders through language. We then show how Tikuna women are resisting ongoing forms of sexual colonisation in Amazonia, revealing the ways the decolonisation of sexualities is central to Indigenous self-determination.

Lost in Colonial Translation

Indigenous sexualities defy LGBT categorisation; they resist translation into the conceptual limits of LGBT categories. Juchitán, internationally depicted as a gay paradise, is known for having gender freedoms in stark contrast with the rest of Mexico. Their Zapotec society recognises muxes as a third gender (Mirandé 2017, 15). The muxes are people who are biologically male but embody a third gender that is neither male nor female, and who refuse to be translated as transvestite. Muxes were traditionally seen as a blessing from the gods; today they remain an integral part of society.

Muxes cannot be reduced to LGBT categorisation, nor can their experience be exported or replicated elsewhere. They are better approached from queer understandings of sexuality as fluid. Elders say that in ancient, pre-colonial Zapotec language there was no difference when referring to a man or a woman; there were no genders. In ancient Zapotec, la-ave referred to people, la-ame to animals, and la-ani to inanimate beings. There was no he or she (Olita 2017). This changed with the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores who introduced the feminine and masculine genders. How are we to translate muxes in languages that are structured around gender? The muxes are just one example of many sexual registries that were lost in colonial translation.

Celebrations of non-heteronormative sexualities abounded before the arrival of Europeans in 1492. Same-sex relations were celebrated in Moche pottery (AD 15–800), along the northern Pacific coast of contemporary Peru. Moche stirrup spout vessels depict a variety of sexual acts but rarely vaginal penetration, emphasising male genitalia and the movement of fluids between bodies as a form of communication (Weismantel 2004). In the Pacific islands, Māori carvings celebrated same-sex and multiple relationships (Te Awekotuku 2003). In the Andes, the Inkas summoned a queer figure called chuqui chinchay to mediate a political crisis in the late fifteenth century (Horswell 2005). The chuqui chinchay, a revered figure in Andean culture, was the mountain deity of the jaguars. It was also the patron of dual-gendered peoples, who acted as shamans in Andean ceremonies. These quariwarmi (man-woman) cross-dressed to mediate the dualism of Andean cosmology, performing rituals that involved same-sex erotic practices. They embodied a third creative force between the masculine and the feminine in Andean philosophy.

Colonisers had a hard time recognising native sexualities for what they were. Colonial chronicles from the sixteenth century to the eighteenth century described non-binary sexualities, telling of genders they could not comprehend (or accept). Will Roscoe (1998, 12–15) gathered colonial documents reporting such accounts. French expeditions in Florida described ‘hermaphrodites’ among the Timucua Indians as early as 1564. Colonial engravings depict them as warriors, hunters, and weavers. In the Mississippi Valley, French colonisers reported a third gender, called ikoueta in Algonkian language, males who adopted gender roles. They went to war, sang in ceremonies, and participated in councils. According to colonial reports, they were holy, and nothing could be decided without their advice. Another French coloniser, Dumont de Montigny, described males that did women’s work and had sex with men among the Natchez in the lower Mississippi region in the eighteenth century. In what is now Texas, the Spanish Cabeza de Vaca reported men who dressed and lived like women. Even Russian traders in the sub-arctic region documented gender diversity among Native communities in what is today Alaska. Despite Russian efforts to suppress third genders, the Chugach and Koniag celebrated those they called ‘two persons in one’ and considered them lucky.

Linguistic registries show that indigenous peoples approached gender as a fluid affair before conquest and assimilation. Roscoe’s linguistic index documents language for alternative genders in over 150 tribes in North America. Alternative genders existed among the Creek, Chickasaw, and Cherokee. In Navajo language, nádleehí means ‘the changing one’. In Osage, Omaha, Kansa, and Oto languages, the term mixu’ga literally means “moon-instructed”, referring to the distinct abilities and identity that the moon conferred them (Roscoe 1998, 13). Alternative genders were often associated with spiritual powers. The Potawatomi considered them extraordinary people. For the Lakota, winkte people had auspicious powers and could predict the future. Lakota warriors visited winkte before going to battle to increase their strength. The he’emane’o directed the important victory-dance because they embodied the central principles of balance and synthesis in Cheyenne philosophy (Roscoe 1998, 14).

Women engaged in same-sex practices and alternative genders that marked lifelong identities. Nearly a third of the groups in Roscoe’s index had ways of referring specifically to women who undertook male roles. Evelyn Blackwood (1984) argues that the female cross-gender role in Native-American contexts constituted an opportunity to assume male roles permanently and to marry women. A trader for the American Fur Company that travelled up the Missouri River reported that Woman Chief, a Crow woman who led men into battle, had four wives and was a respected authority who sat in Crow councils (Roscoe 1998, 78).

Blackwood (1984, 35) argues that Native American ideology among Western tribes dissociated sexual behaviour from concepts of male/female gender roles and was not concerned with gender identity. This means for instance that gender roles did not restrict sexual partners – individuals had a gender identity but not a corresponding sexual identity. In other words, sex was not entangled in gender ideology. Blackwood stresses the unimportance of biological sex for gender roles in native worldviews for Western tribes in the US. There was much overlapping of masculine and feminine, and people who were once married and had kids would later in life pursue same-sex relationships. Roscoe (1998, 10) interprets this fluidity as a distinction between reproductive and non-reproductive sex rather than a distinction between heterosexual and same-sex sexuality. Interpretations vary. What is certain is that Indigenous cultures have long recognised non-heterosexual sexualities and alternative genders, socially respected, integrated, and often revered them.

Sexual Colonisation

This rich diversity in native sexualities took a hard hit with post-1492 colonial expansion, which brutally repressed non-heteronormative practices. Chronicles like the Relación de Servicios en Indias labelled Inka sacred figures like the chuqui chinchay as diabolical and described natives as ‘ruinous people’ who ‘are all sodomites’ – and called for their extermination (Horsewell 2005, 1–2). An infamous example is the 1513 massacre of ‘sodomites’ by Spanish conquistador Vasco Nunez de Balboa in Panama. Balboa threw the brother of Chief Quaraca and 40 of his companions to the dogs for being dressed as women. The brutal killings were engraved in Theodore de Bry’s 1594 Les Grands Voyages. In another macabre episode, French colonisers tie a hermaphrodite to a cannon in northern Brazil. Capuchin priest Yves d’Evreux describes how the French chased the ‘poor Indian’ who was ‘more man than a woman’, and convicted him ‘to purify the land’ (Fernandes and Arisi 2017, 7). The punishment consisted of tying the person’s waist to the mouth of the cannon and making a native chief light the fuse that dismantled the body in front of all other ‘savages’.

Perhaps European colonisers could not understand native sexualities; they did not have the words to. They could not recognise sexualities differing from their own, and, generally, associated native sexualities with immoral, perverse, and unnatural sexualities. Vanita Seth (2010) explains the European difficulty in representing difference as stemming from a broader inability to translate the New World into a familiar language. In that sense, the ‘discovery’ was severely impaired by the colonisers’ inability to convert what they encountered across the New World into accessible language. Yet the colonial destruction of native sexualities is more than a mere inability to see otherness. Labelling native sexualities as unnatural justified violent repression, and the heterosexualisation of Indians was as much a process of modernisation as of dispossession.

Estevão Fernandes and Barbara Arisi (2017) explain how the colonisation of native sexualities imposed a foreign configuration of family and intimate relations in Brazil. The state created bureaucratic structures to civilise the Indians. In the 1750s, the Directory of Indians established administrative control of intimacy and domesticity that restructured sex and gender in daily life. Bureaucratic interventions centred on compulsory heterosexuality, decrying the ‘incivility’ of Indigenous homes where ‘several families (…) live as beasts not following the laws of honesty (…) due to the diversity of the sexes’ (Fernandes and Arisi 2017, 32). Indigenous households were subject to the monogamous ‘laws of honesty’ and Indigenous heterosexualisation initiated the process of civilisation. Rifkin (2011, 9) refers to a similar process in Native North America as ‘heterohomemaking’. Heteronormativity made it impossible for any other sexuality, gender, or family organising to exist. The framing of native sexualities as queer or straight impose the colonial state as the axiomatic unit of political collectivity. Indigenous peoples were forced to translate themselves in terms consistent with the state and its jurisdiction. Sexual codification related to racial boundaries defining access to or exclusion from citizenship and property rights (McClintock 1995).

The historical and linguistic archives are crucial even if they defy translation: they refer to social fabrics that have been largely disrupted, repressed, and destroyed. Each language brought a singular understanding of gender. Indigenous genders cannot be reduced to homo or trans sexuality. It would be an anachronism to translate pre-conquest realities into contemporary frames. In pre-conquest societies, third genders were not an anomaly or difference, but constitutive of a whole. Thus, debates on whether to approach native sexualities as berdache, two-spirit, or third genders miss the point. Native sexualities cannot be reduced to the addition of more genders to established sexual registries; they invoke complex social fabrics that are untranslatable in the limited framework of hetero/homosexuality. They invoked native epistemologies and worldviews beyond sexuality.

Centuries of sexual colonising erased non-Western Indigenous understandings of sexuality. But they are still there. During Brazil’s National Meeting of Indigenous Students in 2017, a group discussed self-determination through issues ranging from land demarcation to LGBT issues. Tipuici Manoki said that homosexuality is taboo among Indian communities, ‘but it exists’.[2] Today, Indigenous peoples often utilise the global sexual rights framework for self-representation and rights claims. In 2013, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights of the Organisation of American States heard the testimonies of elected officials at a panel ‘Situation of the Human Rights of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Indigenous Persons in the Americas’. In the US, at least three tribes have formally recognised marriage equality for same-sex couples. Indigenous sexualities resisted conquest and genocide in their own ways, with words of their own, before and beyond the LGBT framework.

Sexual Resurgence in Amazonia

Resisting is exactly what Indigenous peoples are doing in Amazonia. Originary peoples in Amazonia have long had words to refer to non-heterosexual practice, and their languages may be considered queer by contemporary frameworks. In Tupinambá, tibira is a man who has sex with men and çacoaimbeguira is a woman who has sex with women. The documentary ‘Tibira means gay’ shows the variety of sexual identities in Indigenous communities. Other languages have words for queer practices: cudinhos in Guaicurus, guaxu in Mbya, cunin in Krahò, kudina in Kadiwéu, hawakyni in Javaé.

The Tikuna, one of the largest Indigenous groups in Amazonia, speak an isolate language.[3] In Tikuna, Kaigüwecü is the word that describes a man who has sex with another man; Ngüe Tügümaêgüé describes a woman who has sex with another woman. But these words were unrelated to the Rule of Nations, a central principle of Tikuna society that organises marriage among clans in rules of exogamy. In Tikuna philosophy, to marry well is to marry people from different clans: a member from the clan of the bird (ewi) can marry with a member from the clan of the jaguar (ai), but not a member of its own clan. Unions within a clan are considered incestuous, and therefore unforgivable. In short, Tikuna unions are legitimised along clan lines, not sex. Things started to change, however, with the recent arrival of evangelical missionaries, like the New Neopentacostal Churches, who introduced different expectations about marriage. Rather than worrying about clans, missionaries are concerned with sex, more specifically with regulating sexuality. These churches framed homo-affective relationships as sinful. Progressively, what were uneventful couples under clan lines became abnormal ‘lesbian’ couples in religious rhetoric. Forbidden love was displaced from within the clan to within one’s gender.

Homo-affective Tikuna experiences vary. Some are marginalised by their communities, treated with contempt by their families or even expelled from their homes. Many fear making their sexuality public. ‘Some mothers even forbid their daughters to see me because I am machuda‘[4] said one of them. Discrimination turns into social marginalisation and destroys ties of cultural belonging, making women feel excluded. Some are forced to leave their homes and communities, even to suicide. In other cases, families and communities normalise sexual diversity. This happened to 32-year-old Waire’ena. Her father, a priest in a new Church called Brotherhood of Santa Cruz, was hesitant in accepting his daughter’s sexuality because of the repercussions in the community. As a public religious-political figure, he worried about moral considerations like honour and respect that were elements used to negotiate his legitimacy and social position. He eventually talked to the head priest of his Church, who described the situation as a ‘challenge from God’. That is when he ‘woke up’ tells Waire’ena. He interpreted the challenge to be teaching his followers the tolerance of diverse forms of sexuality as all being blessed by God. His mission became to convince his community to accept his daughter’s homo-affective choices. He talked to people across his Church, preached for same-sex love, and countered homophobia in his community.

Tikuna women too are taking matters into their own hands, invoking the Rule of Nations to defend their autonomy to love in their own Tikuna terms. They defend homo-affective relationships as consistent with the clan rules of exogamy. For Botchicüna, there is little doubt that sexual diversity is intrinsically Indigenous; sexual discrimination was brought in by a vogue of evangelical religions. ‘Our ancestors experienced people living homo-affective lives but never interpreted it as something malicious, it is religion that came to interfere with our culture trying to evangelise us’. Churches introduced lesbianism as a forbidden love, permeating Tikuna cosmovision with exogenous moralities that signal the colonial power of religion over Indigenous peoples. What is detrimental to Tikuna culture is the foreign imposition of religions by missionaries. Homo-affective ties, they claim, respect the Rule of Nations and therefore reinforce Tikuna self-determination.

Tikuna women are invoking ancestrality to battle new waves of homophobia introduced by outsiders. Their homo-affective families raise their children in accordance with ancestral clan lines. Women claim that same-sex relationships give continuity to Tikuna Rule of Nations, insisting on clan lines to secure sexual freedoms. In their experience, culture and sexual autonomy complement one another. Tikuna women are blending political registries, combining ancestral worldviews with current LGBT referents to defend sexual autonomy in their local contexts. In doing so, they are using sexual politics towards Indigenous resurgence. They negotiate current politics to define their world for themselves, reclaiming the past to shape their futures (Aspin and Hutchings 2007).

Are Tikuna societies modern because they permit homo-affective love? The stories of sexual diversity told above invite us to reconsider assumed cartographies of modernity. They debunk notions of natural peripheries isolated from global modernity and embedded in colonial processes. Amazonia is not that disentangled from global dynamics nor a land without (sexual) history. Similarly, narratives that posit sexual liberation as a Western, modern phenomenon need reframing (Rhaman 2014). Their sexual politics are not about modernity and we should not invoke LGBT codification to validate them. Indigenous sexualities defy translation, they refer to political systems beyond frameworks of LGBT rights.

Conclusion

For many Indigenous peoples across the world, diverse sexualities and multiple genders are not a Western introduction. Heteronormativity is. Indigenous intimacies were repressed, pathologised and erased by violent processes of colonial dispossession. Yet Indigenous languages resist so that Indigenous sexualities can resurge. They resist heteronormative colonialism; they embody the possibility of radical resurgence. Indigenous sexualities matter beyond sexual politics because they expand the political imagination, not sexual vocabularies. It is not the decolonisation of Indigenous lifeways alone that is at stake. It is the diversification of ways of knowing that is at stake, our ability to emancipate from one single system of codifying sexualities.

To Indigenise sexualities is a theoretical project: in the sense of moving beyond categorisations and political borders, in the sense of making visible how colonialism and sexuality interact within the perverse logic of modernity. Scholars have exposed the heteronormativity of colonialism (Smith 2010), and insisted on the value of decolonising queer studies and queer decolonial studies (Driskill et al. 2011; Rifkin 2011). In this chapter, we showed how language evokes – and resists – political dynamics. We value Indigenous languages for the plurality of gender roles and sexual practices they encompass. But they do much more than simply expand sexual repertoires. As Fernandes and Arisi (2017) rightly claim, Indigenous sexualities matter because of what we can learn from them, not about them. Indigenous sexualities expand the imagination with new epistemologies.

Notes

[1] Official definitions have varied over time as states manipulate legislation, blood quantum, and census depending on their interest to erase, regulate, or displace Indigenous presence (Kauanui 2008). If Indigenous belonging is contested in the Americas, the concept is even fuzzier in regions that did not experience large European settler immigration, like Asia (Baird 2016).

[2] https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2018/02/01/politica/1517525218_900516.html?id_externo_rsoc=FB_CC

[3] A language isolate has no demonstrable genealogical relationship with other languages. Tikuna is a language isolate with no common ancestry with any other known language.

[4] Machuda, from macho, is a pejorative way to refer to women who have sex with women as masculine not feminine.

References

Aspin, Clive, and Jessica Hutchings. 2007. “Reclaiming the past to inform the future: Contemporary views of Maori sexuality.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 9 (4): 415–427.

Baird, Ian G. 2015. “Translocal assemblages and the circulation of the concept of ‘indigenous peoples’ in Laos.” Political Geography 46: 54–64.

Blackwood, Evelyn. 1984. “Sexuality and gender in certain Native American tribes: The case of cross-gender females.” Signs 10 (1): 27–42.

Cabeza de Vaca, Alvar Nuñez. 1993. Castaways: The Narrative of Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Carvajal, Federico. 2003. Butterflies will burn: Prosecuting Sodomites in Early Modern Spain and Mexico. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Driskill, Qwo-Li, ed. 2011. Queer Indigenous studies: Critical interventions in theory, politics, and literature. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Fernandes, Estevão Rafael, and Barbara M. Arisi. 2017. Gay Indians in Brazil. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Hindess, Barry. 2007. “The past is another culture.” International Political Sociology 1 (4): 325–338.

Horswell, Michael J. 2005. Decolonizing the Sodomite: Queer Tropes of Sexuality in Colonial Andean Culture. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Katz, Jonathan N. 2007. The Invention of Heterosexuality. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Kauanui, Kehaulani. 2008. Hawaiian Blood: Colonialism and the Politics of Sovereignty and Indigeneity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Mirandé, Alfredo. 2017. Behind the Mask: Gender Hybridity in a Zapotec Community. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Morgensen, Scott Lauria. 2011. Spaces between us: Queer settler colonialism and indigenous decolonization. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Murray, David AB. 2003. “Who is Takatāpui? Māori language, sexuality and identity in Aotearoa/New Zealand.” Anthropologica 45 (2): 233–244.

Olita, Ivan. 2017. “Third Gender: An Entrancing Look at México’s Muxes.” Artistic Short Film. National Geographic, Short Film Showcase, February 2017.

Rifkin, Mark. 2011. When did Indians become straight? Kinship, the history of sexuality, and native sovereignty. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Robertson, Carol E. 1989. “The māhū of Hawai’i (an art essay).” Feminist Studies 15 (2): 313.

Roscoe, Will. 1998. Changing Ones: Third and Fourth Genders in Native North America. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

Ruvalcaba, Héctor Domínguez. 2016. Translating the Queer: Body Politics and Transnational Conversations. London, UK: Zed Books.

Seth, Vanita. 2010. Europe’s Indians: Producing Racial Difference, 1500–1900. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Sigal, Pete. 2011. The flower and the scorpion: Sexuality and ritual in early Nahua Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Sigal, Pete. 2007. “Queer nahuatl: Sahagún’s faggots and sodomites, lesbians and hermaphrodites.” Ethnohistory 54 (1): 9–34.

Smith, Andrea. 2010. “Queer theory and native studies: The heteronormativity of settler colonialism.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 16 (1–2): 41–68.

Taiaiake, Alfred and Jeff Corntassel. 2005. “Being Indigenous: Resurgences Against Contemporary Colonialism.” Government and Opposition 40 (4): 597–614.

Te Awekotuku, Ngahuia. 1996. “Maori: People and culture.” Maori Art and Culture: 114–46.

Te Awekotuku, Ngahuia. 2005. “He Reka Ano: same-sex lust and loving in the ancient Maori world.” Outlines Conference: Lesbian & Gay Histories of Aotearoa, 6–9. Wellington, New Zealand: Lesbian & Gay Archives of New Zealand.

Tikuna, Josi and Manuela Picq. 2016. “Queering Amazonia: Homo-Affective Relations among Tikuna Society.” Queering Paradigms V: Queering Narratives of Modernity edited by Marcelo Aguirre, Ana Maria Garzon, Maria Amelia Viteri and Manuela Lavinas Picq. 113–134. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang.

Van Deusen, Nancy. 2015. Global Indios: The Indigenous Struggle for Justice in Sixteenth-Century Spain. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Weismantel, Mary. 2004. “Moche sex pots: reproduction and temporality in ancient South America.” American Anthropologist 106 (3): 495–505.

Wolf, Eric. 1982. Europe and the People Without History. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.