Terrorism has been an existing phenomenon for many years. However, the recent wave of terrorist attacks associated with Islamic extremism, is largely focused on targeting Western liberal democracies and their core values (Manin, 2008). The response to recent terrorist attacks on democratic countries has differed in many ways across countries and does not remain uncontroversial. This essay aims to analyze how the response to large terrorist attacks on democratic ‘soil’ has affected the liberal democracy of the affected country. Two case studies will be compared for this analysis. First, the reaction to (arguably the most notorious) terrorist attacks on the 11th of September 2001 in the United States will be discussed by examining the response of the Bush administration and the change in public discourse and popular culture. Then, the French response to the 2015 Charlie Hebdo and November 13th attacks is evaluated by investigating political and societal consequences of the attacks. By outlining the political and legal measures taken by the respective governments this essay aims to elucidate how responses to terrorism can erode the adherence to liberal democratic values. First, the concepts and theory used for the analysis of the cases will be outlined. Then each case study will be individually explained and analyzed. According to the analysis I will then compare the responses to terrorist attacks in France and the United States, using the existing literature, and formulate a conclusion.

Theoretical Framework:

Terrorism

A broad analysis of the development of terrorism and how terrorism is understood is beyond the scope of this paper. However, to comprehend the implications of terrorist attacks it is crucial

to outline what is understood as terrorism. A popular definition of terrorism describes it as “the substate application of violence or threatened violence intended to sow panic in a society, to weaken or even overthrow the incumbents, and to bring about political change (Lacqueur, 1996, p. 24). However, contemporary societies do not face a single terrorism, but multiple kinds originating from different ideologies and origins (Lacqueur, 1996, p. 25). Furthermore, terrorist threats today more often than not originate from non-state actors (Wilkinson, 2011, p. 6). Although these non-state attacks have historically been less lethal than state terrorism they still succeed in instigating fear and crisis in society (Wilkinson, 2011, p. 6) (Lacqueur, 1996, p. 34). While acknowledging that there are many different terrorist organizations with origins in different ideas or ideologies, this essay will focus on two recent attacks both committed by different jihadist organizations adhering to Islamic extremism on liberal democracies. The two cases were selected based on the fact that both attacks were recent, targeted at liberal democracies and provoked a clear response from the government.

Liberal Democracy

In this essay democracy is defined as “a system of governance in which rulers are held accountable for their actions in the public realm by citizens, acting indirectly through the competition and cooperation of their elected representatives” (Schmitter & Karl, 1991, p.4). A liberal democracy is then understood as a democracy in which minority rights and civil liberties are constitutionally protected (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2012, p. 13).

Separation of Powers

The idea of the separation of powers is most often attributed to Montesquieu, who wrote that “in every government there are three sorts of powers: the legislative, the executive in respect to things dependent on the laws of nations, and the executive in regard to matters that depend upon the civil law” (De Montesquieu, 1949, p. 151). The three branches are also referred to as the legislative branch, executive branch and judiciary branch (De Montesquieu, 1949, p. 151). The legislative branch is concerned with the ratification of laws, the executive branch is in charge of national security and the judiciary branch punishes criminals and solves legal arguments between citizens (De Montesquieu, 1949, p. 151). Montesquieu argues that the branches should be independent from one another in order to ensure that tyranny is avoided as he believes that “when the legislative: and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates, there can be no liberty” (Montesquieu, 1748, p. 151-152). Founding Father of the American Constitution James Madison builds on Montesquieu in number 47 of the Federalist Papers stating that “The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, selfappointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny” (Madison, 2003, p. 298). In number 51 of the Federalist Papers, Madison proposes a system of checks and balances so that each branch can keep the others in check and thus ensure the balance between the three branches (Madison, 2003, p. 317).

Unitary Executive Theory

Unitary executive theory is an American legal theory based on the Constitution which emphasizes the power of the executive branch (Bailey, 2008, p. 453). The Unitary Executive Theory is often associated with Alexander Hamilton who argues in The Federalist Papers 70-72 that unity in the executive branch is safer for democracy as it enables people to extend the accountability of the President (Bailey, 2008, p. 457). Although different interpretations of the theory exist, the main premise holds that, based on the separation of powers and Article 2 of the American Constitution, the executive power is vested in a single officer (Skowronek, 2009, p. 2075). This officer, the President, is argued to possess extensive authority and exclusive responsibility (Skowronek, 2009, p. 2075). This means that, according to supporters of the unitary executive theory, the Constitution endorses a unified executive branch in which all people working in the branch answer to the President, and are subservient to his or her opinion (Skowronek, 2009, p. 2077). Adherents of unitary executive theory often present two main arguments, often referred to as the “democracy claim” and the “managerial claim”, to prove that their theory is in accordance with constitutional democracy (Farina, 2010, p. 373). The democracy claim implies that, as the President is democratically elected to be a representative of the entire American people, the unitary executive theory allows the people to govern themselves and therefore satisfies the requirements of democracy (Farina, 2010, pp. 373-374). The managerial claim holds that a powerful and strong President is more efficient and coordinated than modern regulatory government, which means that the executive branch will be better able to oversee the vast (inter)national policy apparatus and align it with the interest of the people (Farina, 2010, p. 374). However, the unitary executive theory and its claims are heavily disputed, which will become evident in the analysis of the 9/11 case study.

Emergency State

Whereas the unitary executive theory supports a permanent expansion of the President’s authority, the emergency state consists of a temporary measure to increase the authority of the executive branch in response to an emergency (Manin, 2008, p. 23). A state is entitled to declare an emergency state in case of “a public emergency which threatens the life of the nation, and which is officially proclaimed” (Lillich, 1985, p. 1073). A public emergency refers to “an exceptional situation of crisis or public danger, actual or imminent, which affects the whole population or the whole population of the area to which the declaration applies and constitutes a threat to the organized life of the community of which the state is composed” (Lillich, 1985, p. 1073). The emergency state allows for the temporary deviation from higher order norms as described in the Constitution (Manin, 2008, p. 23). These deviations may have a procedural character, meaning a change in the institutional decision-making process, or a substantive character, regarding the content of emergency measures (Manin, 2008, p. 25). There are, however, certain requirements to ensure that the emergency state does not allow for severe infringement on individual rights, such as “The Paris Minimum Standards Of Human Rights Norms In A State Of Emergency” and several international human rights treaties (Lillich, 1985, p. 1072). Minimum requirements for a state to fulfill include, among others, freedom from discrimination, freedom from torture, right to liberty and right to nationality (Lillich, 1985, pp. 1075-1081).

Authoritarian and Illiberal Practices

In her article “What authoritarianism is … and is not: a practice perspective”, Marlies Glasius (2018) argues for a move away from defining authoritarianism and illiberalism merely in the context of regimes, and instead proposing a classification based on authoritarian and illiberal practices which can be attributed to (democratic) governments, people and corporations (p. 523). Practices are understood as “patterned actions that are embedded in particular organized contexts” (Glasius, 2018, p. 523). An authoritarian practice, according to Glasius (2018), is an active practice by a political actor focused on accountability sabotage to the people by disabling access to information and/or disabling their voice (p. 526). An illiberal practice can be described as “a pattern of actions, embedded in an organized context, infringing on the autonomy and dignity of the person” (Glasius, 2018, p. 530). While illiberal and authoritarian practices often go hand in hand, they can also exist independent of each other, and be executed by liberal and democratic governments and organizations.

Analysis of Case Study

Post 9/11 United States: Eroding liberal democracy at home while spreading it abroad

On the 11th of September 2001, 19 members of Al-Qaeda hijacked four airplanes targeting various important landmarks of the United States (Templeton & Lumley, 2002). Two of the airplanes flew into the both towers of the Word Trade Center in New York City, killing 2823 people in the towers and aircraft (Templeton & Lumley, 2002). The third airplane crashed into the Pentagon, killing 189 (Templeton & Lumley, 2002). The last hijacked airplane, which is suspected to have aimed to crash into the Capitol or the White House, crashed to the ground in rural Pennsylvania, taking the life of 45 people (Templeton & Lumley, 2002).

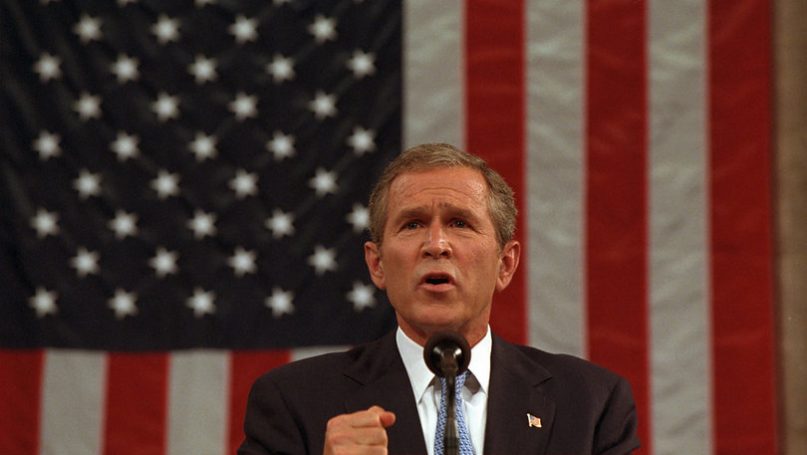

The 9/11 attacks constituted a traumatic experience for the United States, and a grave shock for the rest of the world. The Bush administration was faced with the difficult task of formulating an appropriate response to the sheer terror that had shaken the nation. Nine days after the attacks, in an address to the joint session of Congress, President George W. Bush declared that “On September the 11th, enemies of freedom committed an act of war against our country” (Bush, 2001, p. 66). In that same speech Bush declared a so-called “War On Terror” stating that “Our war on terror begins with al Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated” (Bush, 2001, p. 68). While remarkable, this approach in itself does not pose a significant danger to liberal democracy. However, the way the Bush administration went about this war has several pitfalls.

In order to enable the government to implement the policies required for The War On Terror the Bush Administration and their associates made frequent use of the unitary executive theory. In several memoranda written by legal advisors to the Bush administration the unitary executive theory was used to argue in favor of granting the President sole and extensive power to respond to terrorism (Schultz, 2008, p. 213). The Yoo Memorandum, named after writer John Yoo, consisted of the main claim that the President has full control over foreign and military powers in the event of a terrorist threat (Schultz, 2008, p. 215). Two other critical memoranda concerned the treatment of detainees and suspects of terrorist activity (Schultz, 2008). The so-called Detainee Memo concluded that, as the President has the sole power to suspend and continue treaties, Bush had the right to temporarily suspend the Geneva convention about the prisoner of war status (Schultz, 2008, 216). A memo strongly related to this is the Gonzales or Torture Memo which states that the use of torture is in accordance with the Convention Against Torture, as long as it is not performed purely for the sake of inflicting severe mental of physical suffering (Schultz, 2008, p. 221). Furthermore, the memo argues that even if the use of torture would violate the law, it would be unconstitutional to limit the presidential war-making powers (Schultz, 2008, p. 221). The last memo, The Wiretapping Memo, was written after it was exposed that the Bush administration spied on American citizens without court-approved warrants (Schultz, 2008, p. 221). The Memo defended the Presidents’ use of surveillance by arguing that the President has the authority to engage in searches without warrants for foreign intelligence purposes (Schultz, 2008, p. 222). It can be concluded that the Bush administration used the unitary executive theory to justify and enable the actions taken in light of the War on Terror. However, many of these actions, such as the wiretapping of citizens and the use of torture, are in violation of the rule of law, human rights and civil liberties (Brysk, 2007).

An important policy response to 9/11 concerned intelligence information. The USA PATRIOT Act, realized on the 26th of October 2001, was an important step towards increasing the authority of law enforcement and intelligence agencies (Schultz, 2008, p. 210). Aimed at making it easier to detect domestic terrorism, the law further facilitated the use of intelligence information by crime control officials (Schultz, 2008, p. 210). However, by disproportionately concerning immigrants and foreign visitors the Patriot Act can be said to have had a stigmatizing effect (Schultz, 2008, p. 211). Another controversy regarding American intelligence operations initiated after 9/11 is the covert wiretapping of international telephone and email conversations without legal warrants, ultimately resulting in the spying of American citizens (Schultz, 2008, p. 2008). According to the classification of Marlies Glasius (2018) this clearly constitutes an illiberal practice which infringes on the privacy and autonomy of individuals. Furthermore, after the introduction of the Patriot Act, the Bush administration restricted access to printed, government and scientific information leading to the erosion of free speech and the quality of democratic dialogue (Jaeger & Burnett, 2005, p. 475). The disabling of access clearly constitutes an authoritarian practice and is not in line with democratic thought (Glasius, 2018). Whereas the government has increased their ability to gather information about the behavior and background of individuals, they simultaneously decreased the ability of the people to inform and express themselves and become critical citizens (Jaegar & Burnett, 2005, p. 475). Furthermore, using the frame of war, people who voiced their critical opinion of the War on Terror were often considered betrayers of the country (Butterworth, 2006, p. 109). This amounts to an authoritarian practice as it focuses on disabling critical voices (Glasius, 2018). In a way one could conclude that the 9/11 terrorist attacks fulfilled their main purpose – the erosion of liberal and democratic values – by provoking a response by the American government which effectuated just that.

France after 2015: Liberal democratic values and permanent emergencies

In January 2015, the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo was the target of a terrorist attack by two radicalized Muslims, ending in the murder of 12 people (Połońska-Kimunguyi & Gillespie, 2016, p. 569). The attack was inspired by cartoons the magazine had published, depicting the prophet Mohammed (Połońska-Kimunguyi & Gillespie, 2016, p. 569). Later in 2015, France was again the target of terrorism, when 137 people were killed by jihadists in various coordinated attacks in Paris (Neiberg, 2017, p. 25). In a speech after the November attacks, French President Francois Hollande (2015) referred to the event as an act of war.

Shortly after the November attacks, Hollande announced a national emergency state, which would eventually end up lasting two years (Feinberg, 2018 p. 496). The state of emergency temporarily increases the authority of the executive branch, allowing for “the creation of zones of protection and security; the imposition of curfews, traffic stops, and searches; house arrest for individuals whose activity was deemed dangerous; and administrative searches”, as well as the large-scale collection of digital data (Feinberg, 2018, p. 496). Under the emergency state 4469 administrative searches, 754 house arrests, and the closure of 19 religious spaces were carried out (Feinberg, 2018, p. 496). It was indicated that many of the measures taken were unrelated to the 2015 attacks (Feinberg, 2018, p. 496). Even though executive power was expanded, there was still a limited degree of judicial review, which was later criticized for only performing a posteriori reviews (Feinberg, 2018, p. 501). The main issue with the French emergency state, however, concerns the temporal element. By continuously extending the state of emergency, exceptional measures are increasingly normalized in society leading to a distorted view on the liberal democratic state (Feinberg, 2018). This argument is also supported by Manin (2008) who argues that “Short duration is a necessary condition for emergency measures to be consistent with constitutional values” (p. 33). However, the terrorist threat posed by Islamic extremism is unlikely to disappear soon based on the historical pattern of terrorism, the organizational structures of networks as Al Qaeda and the advanced use of technology by terrorists (Manin, 2008, pp. 30-32). This would indicate that the emergency state is an inappropriate response to modern terrorism. In the case of France, the termination of the emergency state was enabled by the adoption of a new counterterrorism law which contained elements from emergency legislation and brought them into regular law, creating so-called permanent emergencies (Feinberg, 2018, p. 497).

There were a few more problematic elements to the French response. Shortly after the November terror attacks, President Hollande announced his aim to make it easier to denaturalize citizens who were involved in an attack against the nation, even if they were born in France (but only if they also possess another nationality) (Beauchamps, 2017, p. 48). This means that this measure would only affect those who were born in France but enjoy an additional nationality, or those who gained the French nationality through acquisition (Beauchamps, 2017, p. 49). This differentiation can be considered problematic, as it generates a principle of unequal citizenship in which the right to national identity is conditional for some and irrevocable for others (Beauchamps, 2017, p. 49). Depriving a French-born citizen or new national of their nationality takes away the fundamental rights that come with personal identity (Duhamel, 2016, p. 4). Denaturalization is therefore problematic, considering the principle of discrimination and human rights. Another policy by the French government targeted pro-jihad websites (Goodman, 2016, p. 229). While this is, in principle, a proportionate response to the increasing online activity of terrorist organization, the definition of a terrorist website provided by the French government is too blurry, risking extensive censorship which could constitute an authoritarian practice (Goodman, 2016, p. 231) (Glasius, 2018). Even though the French response to terror seems less radical than the American one, the unusually long state of emergency normalized the use of exceptional measures and led to a distortion of civil liberties and liberal democratic values.

Conclusion

As can be derived from the analysis of the case studies, both the French and American governments responded to terror by increasing the authority of the executive branch. However, the respective responses differed in the method by which authority was extended. While the prolonged emergency state in France was considered slightly more legitimate than the Bush administrations’ usage of unitary executive theory, both approaches are questionable when it comes to the protection and conservation of civil liberties and liberal democratic values. As the nature of terrorism has changed, so should our responses. Future research should therefore focus on trying to establish possible responses to terrorism attacks which provide effectiveness and security, while simultaneously harboring liberal democracy and its values. This paper nevertheless implies that, even though terrorist attacks are deemed threats to liberal democracy, perhaps the real danger lurks in how we respond to them.

References:

Bailey, J. D. (2008). The New Unitary Executive and Democratic Theory: The Problem of Alexander Hamilton. The American Political Science Review,102(4), 453-465. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/27644538.

Beauchamps, M. (2016). Perverse Tactics: ‘Terrorism’ and National Identity in France. Culture, Theory and Critique,58(1), 48-61. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/14735784.2015.1137480.

Brysk, A. (2007). Human Rights and National Insecurity. In National Insecurity and Human Rights: Democracies Debate Counterterrorism (1st ed., pp. 1-13). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Bush, G. W. (2001, September 20). Address to the Joint Session of the 107th Congress. Speech, Washington. Retrieved from https://georgewbushwhitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/bushrecord/documents/Selected_Speeches_George_W_Bush.pdf.

Butterworth, M. L. (2006). Ritual in the “Church of Baseball”: Suppressing the Discourse of Democracy after 9/11. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies,2(2), 107-129. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/14791420500082635.

De Montesquieu, B. (1949). The Spirit of the Laws (T. Nugent, Trans.). New York, NY: Hafner Publishing Company.

Duhamel, O. (2016). Terrorism and Constitutional Amendment in France. European Constitutional Law Review,12, 1-5. doi:10.1017/S1574019616000067

Farina, C. R. (2010). False Comfort and Impossible Promises: Uncertainty, Information Overload, and the Unitary Executive. University of Pennsylvania Journal Of Constitutional Law,12(2), 357-424. Retrieved from https://heinonline-org.proxy.uba.uva.nl:2443/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/upjcl12&i=361.

Feinberg, M. (2018). States of emergency in France and Israel – terrorism, “permanent emergencies”, and democracy. Zeitschrift Für Politikwissenschaft,28(4), 495-506. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s41358-018-0147-y.

Glasius, M. (2018). What Authoritarianism is … and is Not: A Practice Perspective. International Affairs,94(3), 515-533. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiy060.

Goodman, A. (2016). Blocking Pro-Terrorist Websites: A Balance Between Individual Liberty and National Security in France. Southwestern Journal of International Law,22, 209-238. Retrieved from https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/sjlta22÷=12&id=&page=.

Hollande, F. (2015, November 13). Address to the French people. Speech, Paris. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/11/13/it-is-horror-french-president-hollandes-remarks-after-paris-attacks/?utm_term=.a8fdafe59b36

Jaeger, P. T., & Burnett, G. (2005). Information Access and Exchange Among Small Worlds in a Democratic Society: The Role of Policy in Shaping Information Behavior in the Post-9/11 Unites States. Library Quarterly,75(4), 464-495. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/502787.

Laqueur, W. (1996). Postmodern Terrorism. Foreign Affairs,75(5), 24-36. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/20047741?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Lillich, R. B. (1985). The Paris Minimum Standards of Human Rights Norms in a State of Emergency. The American Journal of International Law,79(4), 1072-1081. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/2201848.

Madison, J., Hamilton, A., & Jay, J. (2003). The Federalist Papers (C. R. Kesler, Ed.). New York, NY: Penguin Group.

Manin, B. (2008). The Emergency Paradigm and the New Terrorism: What if the end of terrorism was not in sight? In S. Baume & B. Fontana (Eds.), Les Usages de la Sparation des Pouvoirs(pp. 136-171). Paris: Michel Houdiard.

Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2012). Populism and (liberal) democracy: A framework for analysis. In Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or corrective for democracy? (pp. 1-26). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press

Neiberg, M. S. (2017). “No More Elsewhere”: France Faces the New Wave of Terrorism. The Washington Quarterly,40(1), 21-38. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2017.1302736.

Połońska-Kimunguyi, E., & Gillespie, M. (2016). Terrorism discourse on French international broadcasting: France 24 and the case of Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris. European Journal of Communication,31(5), 568-583. doi:10.1177/0267323116669453

Schmitter, P., & Karl, T. L. (1991). What Democracy is…and is not. Journal of Democracy,2 (3), 3-16. Retrieved from http://www.ned.org/docs/Philippe-C-Schmitter-and-Terry-Lynn-Karl-What-Democracy-is-and-Is-Not.pdf

Schultz, D. (2008). Democracy on Trial: Terrorism, Crime, And National Security Policy in a Post 9-11 World. Golden Gate University Law Review,38, 195-248. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/ggulrev/vol38/iss2/2/

Skowronek, S. (2009). The Conservative Insurgency And Presidential Power: A Developmental Perspective On The Unitary Executive. Harvard Law Review,122(8), 2070-2103. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40379786.

Templeton, T., & Lumley, T. (2002, August 18). 9/11 in numbers. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/aug/18/usa.terrorism

Wilkinson, P. (2011). Terrorism Versus Democracy: The Liberal State Response(3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Written at: University of Amsterdam

Written for: Rutger Kaput

Date written: March 2019

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Are Non-democracies More Susceptible to Coups than Democracies in West Africa?

- Drones, Aid and Education: The Three Ways to Counter Terrorism

- Balancing Rivalry and Cooperation: Japan’s Response to the BRI in Southeast Asia

- Terrorism as a Weapon of the Strong? A Postcolonial Analysis of Terrorism

- Terrorism as Controversy: The Shifting Definition of Terrorism in State Politics

- Assessing Global Response to Rising Sea Levels: Who Needs to Be Involved?