The Arms Export Control Act (AECA) dates to 1968 (then referred to as the Foreign Military Sales Act (FMSA)) and is the “basic U.S. law providing the authority and general rules for the conduct of foreign military sales and commercial sales of defense articles, defense services, and training” (DSCA, n.d.). A 2008 amendment to the AECA commits the United States (U.S.) to ensuring Israel’s ability “to counter and defeat any credible conventional military threat from any individual state or possible coalition of states or from non-state actors” (or its “Qualitative Military Edge” (QME), as the law defines). This law codifies decades-old policy dating back to U.S. interests in the region during the Cold War, elevating Israel’s posture as a militarily capable ally and countering Soviet influences in the Middle East. In its current manifestation, however, this law shifts the attention of U.S. national security interests in the region by 1) establishing the definition of QME, 2) mandating recurring certification of Israel’s QME to Congress, and 3) requiring congressional review of all proposed U.S. defense exports to Middle Eastern countries in furtherance of the same (Wunderle and Briere 2008).

Why, as of October 2020, has the U.S. government committed itself to ensuring Israel’s ability “to counter and defeat any credible conventional military threat,” as outlined in the 2008 amendment to the AECA? This analytical research paper argues that, as of October 2020, the U.S. government has committed itself to ensuring Israel’s ability “to counter and defeat any credible conventional military threat,” as outlined in the 2008 amendment to the AECA, to support perceived national security interests for countering and containing Iran, as reflected in 1) the codification of the decades-long strategy to selectively supply arms with the intent to secure Israel’s continued materiel advantage against U.S. adversaries; and 2) the incentivizing of Arab states to normalize relations with Israel through expanded arms transfer opportunities; which together, 3) promotes U.S. strategy to strengthen the coalition of anti-Iranian states in the region and bolster its relative power against Iran.

Concepts & Methodology

Concepts

The international relations concepts examined in this analytical research paper include: the security dilemma, collective security, national interests, and power. The security dilemma refers to the incompatibility of national security interests that occurs when a state pursues an increased security posture that is perceived to violate the inherent desire for self-preservation of another (Jervis, 2017, 75-76). This incompatibility, depending on one’s international relations perspective, can result in tension (as evidenced primarily by American-Israeli-Iranian relations) or the advent of concessions (as evidenced by some American-Israeli-Arab relations).

The possibility of concessions leads to the topic of collective security. Collective security is stability in the international arena built upon cooperation instead of competition, resulting from agreements and burden sharing between partnered states, that creates a preponderance against an aggressor state while serving to more clearly identify the aggressor state (in this case Iran) (Kupchan, 1997, 44-45).

Finally, national interests refer to the objectives of preserving or securing relative power — “the animus dominandi, the desire to dominate” being central to international political activity, according to Hans Morgenthau – through which a state bases its international relations policies and decisions (Pham, 2008, 258). In the context of this paper, national interest will be considered through the arms transfer policies and security assistance the U.S. employs to simultaneously supply aid to Israel and Arab partners while accomplishing its primary objective of advancing perceived national security interests in the region.

Methodology

This research will employ a qualitative approach, utilizing logical inference through a review of both historical analysis and case studies to offer evidence that 1) the U.S. views arms transfers as a tool to support its national security interests overseas, and 2) that its commitment to Israel’s relative military strength in the Middle East is a method to counter and contain Iran. The research will leverage primary sources (in the form of direct statements and formal U.S. government policy and law) and secondary sources (in the form of scholarly works on the topics obtained through academic databases and peer-reviewed journals). This paper will also include arms transfer values obtained through the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) Arms Transfers Database to demonstrate trends in support of the historical analysis and case studies. Rather than relying on financial values of arms transfers, which may be inconsistent between parties and over the course of years, SIPRI utilizes a common “Trend Indicator Value” (TIV) developed on known unit production costs of different types of weapons. Doing so allows for consistency of analysis between suppliers and recipient states over time (SIPRI, n.d.).

The paper will begin with a literature review of existing research on the topics of “carrot” styled arms transfer policies, triadic arms transfer relationships in international relations, and national interests as they relate to the security dilemma. A combination of historical analysis and case studies will follow to review the U.S.-Israeli arms transfer relationship, U.S.-Arab arms transfer relationships, and the context in which these relationships evolved. Historical analysis will include a review of U.S. arms transfer policy, like the AECA and the 2008 amendment. Case studies will include reviews of arms transfers and other cooperative security agreements with Israel and other countries in the Middle East, and commitments by U.S. Government officials as to the value of the U.S.’s materiel support relationship with Israel and its broader effects across the region. An inherent limitation to this approach is that the data available is restricted to the public domain, meaning analysis will be structured upon unclassified policy and public statements issued by U.S. Government officials, and the review of publicly released statements of arms transfer agreements and academic analysis of arms transfer trends. As such, the proof of a causal relationship between U.S. national security interests vis-a-vis Iran and the application of the 2008 amendment cannot be made.

Literature Review

While substantive academic literature regarding the U.S.’s foreign policy position for Israeli QME is limited, relevant literature exists surrounding the underlying themes of arms transfer incentives, triadic relationship in international relations, and the relationship between national interests and the security dilemma. The first theme is a collection of literature which examines whether incentivized, or “carrot” style, arms transfer policies successfully advance national security interests of the supplier state. The second theme includes literature analyzing triadic relationships in international relations to determine if the presence of a third, indirect state results in the promotion of stability and the reduction of tensions between two directly conflicting states. Finally, the third theme provides literature on the general topic of national interests and whether it has a direct relationship to the security dilemma. The following literature review is organized chronologically along these three themes, including summarized comparisons.

“Carrot” Style Arms Transfer Policy

Collectively, there exists considerable research on the relationship between a state’s, particularly the U.S.’s, application of its arms transfer policy and its ability to impose its national interests on a recipient state’s actions. Although some research suggests that intervening conditions between the supplier and recipient state are better determinants of the success of arms transfer manipulation (Sislin 1994) or that globalization has reduced the effectiveness of arms transfer policy (Keller and Nolan 2001, 191), a number of studies support the concept that arms transfer incentives are successful at positively influencing recipient state actions to support supplier state interests. For example, some studies found that arms transfer strategies were direct outcomes of calculating available options in reference to the supplying state’s national interests (Yarhi-Milo, Lanoszka and Cooper 2016), including acquisition and sustainment benefits (Teeney 2010). Indeed others, which included vignettes on U.S.-Israeli relations, demonstrated that despite perceived misalignment of Israeli and U.S. perception of their arms transfer relationship (Wunderle and Briere 2008) or broader national security objectives (Rodman 2019), U.S. arms transfer strategies were successful in shifting Israeli actions. Finally, with respect to the topic of globalization as a component to arms transfer strategy, Neuman (2010) directly contrasted Keller and Nolan (2001), finding that the globalized market actually enhanced the U.S.’s success in advancing its national interests by leveraging its competitive advantage in the defense market rather than capitalism serving as a detractor from responsible U.S. foreign policy.

Triadic Relationships & Arms Transfers

The research on triadic international relations specific to arms transfer is rather limited. Most of the available research found little support for the idea that triadic arms transfer relationships contribute to stability while indirectly supporting findings in the previous theme. Some studies revealed that triadic relationships were, at best, inconsistent and perhaps more attributable to the motives of the supplying state (Sanjian 2003; Baghat and Sharp 2014) and to emboldened recipient state motives (Berrigan 2009). One study, however, found a positive relationship between triadic aid and heightened stability, though it found only limited support when the aid was in the form of arms transfers (Mintz and Heo 2014).

Security Dilemma

Significant literature exists on the topic of security dilemma, and its intersection with national interests is routinely debated within its research. For the sake of this review, dueling perspectives from Robert Jervis and Hans Morgenthau are examined. According to Jervis (2017) in Perception and Misperception in International Politics, security interests of dueling states are inherently incompatible, meaning the pursuit of security (even non-maliciously) is an invitation for the security dilemma (75-76). Morgenthau, as referenced by James Dougherty and Robert Pfaltzgraff (2001) in Contending Theories of International Relations: A Comprehensive Survey, offers a nuanced alternative – that the primary national interest of the state is survival and that this is best achieved through the maintenance of the status quo (76-77).

Conclusion

The literature across the three themes examined herein reveals several gaps for which this paper aims to provide insights. First, the literature offers majority support for the concept of advancing strategic interests by influencing foreign partners with the promise of arms transfers. However, the research is split on whether its applicability to U.S.-Israeli relations is due to general alignment of interests, and it fails to address if this is considered as part of the U.S.’s arms transfer strategy with Israel. Second, in reviewing triadic relationships, the literature offers insights into the stabilizing and destabilizing effects of third-state arms transfers into dyadic states in conflict, but this fails to address whether supplying states can promote increased cooperation and dyadic normalization through arms transfer incentives. Finally, realist and neorealist theory on national interests and the security dilemma offer perspectives on how equipping affects power balances and risk of conflict, but more could be considered with respect to the possibility of concessions and the promotion of cooperative security.

Main Arguments

The 2008 amendment to the AECA mandates certification by the President (or designated representative) to Congress that any “proposed sale or export of defense articles or defense services under this section [of the law] to any country in the Middle East other than Israel shall include a determination that the sale or export of the defense articles or defense services will not adversely affect Israel’s qualitative military edge over military threats to Israel.” It specifies that the certification must include an explanation of Israel’s capacity to address the improved capability, an evaluation of how the transfer would alter the “strategic and tactical balance” in the Middle East, identification of any additional training or capabilities Israel requires to retain its QME, and a description of additional assurances the U.S. makes to Israel in connection to the transfer (U.S. Code, n.d.)

This section will first examine Israeli QME, both as a historic but non-legal foreign policy strategy and in the context of the 2008 amendment to the AECA, from the standpoint of establishing its edge and the strategic value to the U.S. of doing so. Next, the focus will shift to the more tangible effects of this policy with respect to equipping Middle Eastern partners other than Israel. Most importantly, it argues that two portions of the certification requirement, the evaluation of the regional strategic balance and the description of additional assurances to Israel, provide flexibility in the law by offering the opportunity for coalition building and an assurance of peace. Finally, the two concepts will be joined utilizing evidence from U.S. and foreign officials to show that the collective efforts support the building of a regional coalition to counter and contain Iran.

Ensuring Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge to Counter U.S. Adversaries Operating in the Middle East

The 2008 amendment to the AECA is a codification of longstanding policy to leverage Israeli security as a tool to counter the U.S.’s competitors in the Middle East. The U.S.’s interests in Israel’s security date back to the establishment of the new state in 1948, but through the mid-1960s, U.S. support was largely diplomatic and interested in regional stability. At the time, France was Israel’s primary supplier of military technology, and the U.S. was uncommitted to ensuring Israel’s qualitative edge — a doctrine which originated by former Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion — over Arab states (Wunderle and Briere 2008). This began to change in 1968 when, in the escalating Cold War with Russia, the Lyndon B. Johnson administration supplied F-4 Phantoms to Israel as part of a tit-for-tat strategy for undermining Russian influence in the region. In fact, the U.S. had previously pursued a policy to avoid involvement in any arms races in the Middle East (Tominaga 2015, 304). Israel, at the time, was in the midst of territorial conflicts originating with the 1967 Six Day War with Egypt, Jordan and Syria, which were each being supplied military equipment from the Soviet Union. Despite its efforts to support and implement the provisions of United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 242 later that year, which aimed to create an Arab-Israeli peace agreement, the U.S. relented on limiting its arms to the region in order to respond to growing Soviet influence (Rodman, 35).

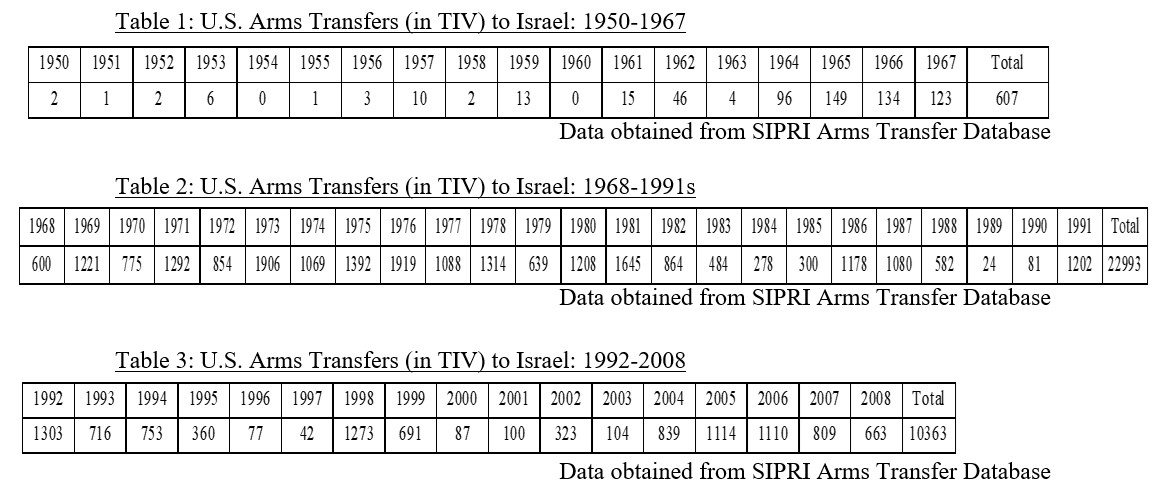

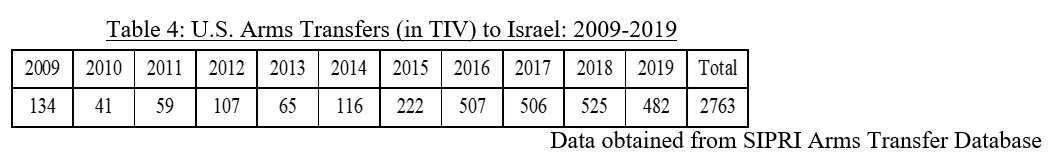

Thus, the 1968 transfer of fighter-bomber aircraft began a U.S.-Israeli security cooperation relationship loosely structured upon Israeli survival and U.S. strategic interests vis-a-vis the Soviet Union. Tables 2 and 3 (all figures Trend Indicator Values (TIV)) below shows that prior to 1968 (beginning in 1950 when data became available), the U.S. supplied approximately $607M worth of military equipment to Israel, averaging approximately $33.7M a year. The U.S. nearly matched that period’s figure the following year (1968) at $600M, and between then and the end of the Cold War in 1991, U.S. arms transfers to Israel totaled $22.993B, averaging approximately $958M a year.

In the later years of the Cold War, a second strategic threat emerged to the U.S. in the Middle East. Following years of warming international relations, Iran underwent a revolution in 1979 which resulted in the severing of diplomatic relations with the U.S. in 1980 (Bahgat 2017, 93). The years that followed saw the Iranian hostage crisis at the U.S. embassy, the Iran-Iraq War, and growing tensions related to Iranian pursuit of nuclear capabilities. With the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the U.S.’s strategic bogeyman in the Middle East shifted to Iran, a notably less-capable threat than the former Soviet Union. Nevertheless, as Table 3 shows below, despite a drop in yearly arms transfers between 1992 and 2008 compared to its Cold War averages, the U.S. supplied on average of approximately $609.6M in military equipment a year to sustain its democratic ally in Israel. After 2008, and through 2019 when the data ends (see Table 4), the yearly average of U.S. transfers to Israel dropped once again to approximately $251.2M.

Generally, in the years leading up to the establishment of the 2008 amendment to the AECA, George W. Bush’s second presidential term in particular, U.S. arms transfers to Israel were elevated. Following its passage, and as the White House transitioned to the Obama administration, U.S. arms transfers to Israel fell, only to rise once again as the Trump administration entered office. While specific details for explaining this variation in arms transfers was not located, events transpiring during the respective administrations offer some insights. During the Bush administration, for instance, the U.S. was heavily embroiled in wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In general, the Middle East and Southwest Asia were strategic themes for the Bush White House. During the Obama administration, however, the U.S. made attempts to shift attention from counterinsurgency operations in the Middle East and Southwest Asia to prioritizing great power competition in the Asia-Pacific. While Iran remained a priority, the U.S. pursued an international agreement to limit Iranian pursuit for nuclear capabilities while easing sanctions, an arrangement referred to as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The Trump administration, alternatively, has been highly critical of the JCPOA, unilaterally removing the U.S. from the agreement – much to the dismay of the foreign partners with whom it was arranged – and raising tensions once again with Tehran (Bahgat 2017, 93). Tensions reached a near “tipping point” in the beginning of 2020 when President Trump authorized a drone attack on the leader of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) Quds Force, Qasem Soleimani (Cohen et al. 2020).

Since the 2008 amendment, however, the overall value of U.S. arms transfers to Israel has better resembled those of the pre-Cold War levels. At first glance, these findings seem inconsistent with the U.S. mandate to ensure Israeli QME; however, QME is assessed holistically rather than through simple trends in bilateral arms transfer values. For instance, in the decade preceding the 2008 amendment, U.S. foreign military financing (FMF; a U.S. program providing grants for weapons purchases) accounted for one-third of Israel’s overall defense budget. Since then, Israeli budget plans doubled, meaning the U.S.’s burden share could decrease while Israeli domestic investment in military capacity continued to grow (Berrigan 2009, 8).

While today, the legacy of propping Israeli security to furtherof U.S. interests continues through a primary focus of Israeli materiel supremacy in the region as codified in the 2008 amendment, application of this amendment offers opportunities to harness support from Arab states who face a similar threat from Iran (Wunderle and Briere 2008). That is, while the U.S. commitment to Israeli QME is mandated by law, as certified by the President to Congress, its security is achievable through a dual approach that includes improving Israel’s relations with neighboring states. One important aspect of this is understanding how U.S. arms transfer relations with other Middle Eastern states has evolved, especially relative to improving Arab-Israeli relations.

Incentivizing Arab-Israeli Relations Through Advanced Materiel Support to Arab Allies in the Middle East

As Soviet influence in the region waned in the later years of the Cold War, and as the U.S.’s attention transitioned to focus more squarely on a more hostile Iran, U.S. arms transfer strategy to Arab states evolved. The U.S. has supplied Middle Eastern partners with scaled capabilities in support of maintaining Israeli QME for decades; however, expansions in the delivered technology have been used as incentives to promote Arab-Israeli peace. Three instances are particularly revealing of this strategy: 1) the Egypt-Israeli Peace Treaty of 1979; 2) the Jordan-Israel Peace Treaty of 1994; and today’s “Abraham Accords” between Israel, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates (U.A.E.).

While two of the examples herein pre-date the 2008 update to the law, they serve as precedent for the development of the language. Recall that two portions of the certification required by the 2008 amendment to the AECA directly support this type of activity. First, “a detailed evaluation of how such a sale or export alters the strategic and tactical balance in the region…” establishes the foundation for examining the totality of circumstances that may reveal the benefit of the transfer (U.S. Code, Title 22, Chapter 29, n.d.). If Israeli security is supported by a preponderance of materiel capability against a shared enemy, then the spirit of the law is observed. Second, “a description of any additional United States security assurances to Israel made, or requested to be made, in connection with, or as a result of, such sale or export” offers room for U.S.-brokered peace agreements to serve as rationale for delivering advanced capability following ratification of the agreement (U.S. Code, Title 22, Chapter 29, n.d.).

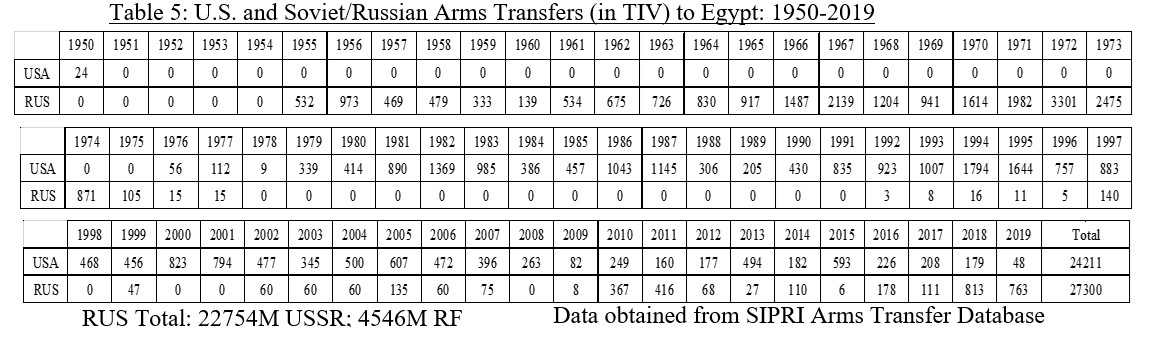

In 1978, when leaders from Israel and Egypt met at Camp David to consider the details of an Egypt-Israeli peace agreement, Iran was descending into the revolution that severed ties with the U.S. and was becoming increasingly recognized as a growing threat (Childs 2019, 166). Recall that only a decade prior, the U.S. was supplying aircraft and other support in response to the Six Days War, and up until the peace treaty was ratified, the Soviet Union was the overwhelming benefactor to Egyptian military aid. In fact, as detailed in Table 5 below, the U.S. provided nearly no arms transfers to Egypt until the provision of military technology was used as an incentive to secure Egypt-Israeli peace. Since then, and as post-Soviet support dwindled, the U.S. has served as Egypt’s primary provider, with Russian aid only recently surpassing that of the U.S.

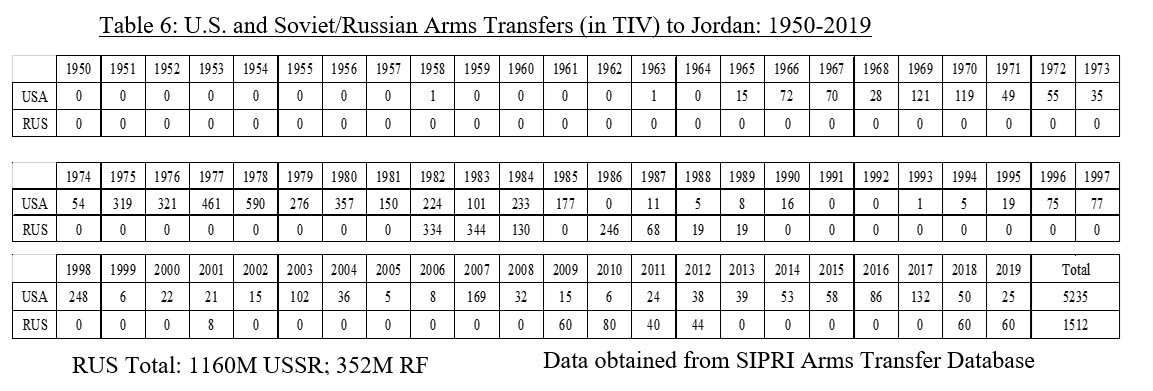

Since U.S. arms transfers began to supply Jordan in the mid-1960s (see Table 6), the two enjoyed a rather fruitful arms transfer relationship. Simmering relations with Israel and Jordan’s siding with Iraq during the First Gulf War saw reductions and, at times, outright discontinuation of arms transfers from the U.S. This trend was corrected, along with other economic aid, as an incentive in support of the 1994 Jordan-Israel peace treaty (Lobell 2008, 91-92). In 1996, Jordan was designated a major non-NATO ally and has since become one of the top recipients of U.S. FMF aid, military education and training, and retains a healthy military sales relationship with the U.S. (Department of State 2020).

Often a niche topic in the field of U.S. foreign policy, Israeli QME became a hot topic over the summer and fall months of 2020. Amid U.S.-facilitated peace deals between Israel and both the U.A.E. and Bahrain, U.S. and the U.A.E. are discussing potential transfers of the F-35, which, within the Middle East, is only offered to Israel at this time (DeYoung and Gearan 2020). This proposal has raised concerns, both domestically with Congressional leaders concerned about the U.S. commitment to Israeli QME, and in Israel which views this as a potential threat to its materiel advantage (Zilber 2020). As of late September 2020, following the signing of the U.A.E.-Israeli peace agreement, the Emiratis have submitted a new formal request to obtain the most advanced version of the aircraft allowable by U.S. policy. This trend of Arab-Israeli normalization (the first formal efforts since 1994) and the provision of additional military technology is part of a shift to further alienate Iran and aligned forces in the region (Capaccio 2020).

While it cannot be emphatically stated that Arab-Israeli normalization was the sole motivation behind each of these arms transfer arrangements, it is difficult to ignore the weight of the U.S.’s emphasis on Israeli security in encouraging warming relations with other similarly postured states in the Middle East with respect to their views on Russia and Iran. Note, especially, that the data shows in the first two examples that Egyptian and Jordanian reliance on Russian materiel support effectively ceased following their peace agreements with Israel. There is a clear linkage between the strategy to secure Israeli QME, the normalization of Arab-Israeli relations, and the views select Arab states retain toward the belligerence of the U.S.’s competitors in the Middle East.

QME and Arab-Israeli Collective Security to Counter Iran

Thus far, the research has demonstrated that Israel’s security, and the U.S.’s commitment through military aid, is based on an underlying strategy of establishing an ally in the Middle East that is postured to counter strategic threats to the U.S. This began with Cold War-era Soviet influence in the Middle East and is carried forward with enduring challenges with Iran. The research has also demonstrated a pattern of relaxing U.S. arms transfer restrictions to Arab partners, and an increase in military investment, as Arab-Israeli normalization occurs. While logical inferences can be drawn as to the combined arms transfer approaches between Israel and Arab states, there also exists direct evidence that U.S. support to Israel, coupled with incentivized arms transfer to Arab partners, is part of a U.S. strategy to generate an Arab-Israeli coalition to counter the U.S.’s adversaries, especially since the enactment of the 2008 amendment to the AECA.

Title 22 of the U.S. Code (Foreign Relations and Intercourse), Chapter 49 (Support of Peace Treaty Between Egypt and Israel) was developed in response to the previously reviewed peace deal between Egypt and Israel. An entire section (§3402. Supplemental authorization of foreign military sales loan guaranties for Egypt and Israel) addresses the rationale, monetary value, and conditions for supplying military aid to Egypt. The first paragraph states, “The Congress finds that the legitimate defense interests of Israel and Egypt require a one-time extraordinary assistance package due to Israel’s phased withdrawal from the Sinai and Egypt’s shift from reliance on Soviet weaponry” (U.S. Code, Title 22, Chapter 49, n.d.). This single statement establishes that equipping Egypt is an added value to both its and Israel’s collective security, while also addressing the value to U.S. strategic interests in shifting partners’ reliance away from Soviet-manufactured military technology.

During the Obama Administration, Andrew Shapiro, the Assistant Secretary for the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs at the State Department – the organization directly responsible for the U.S.’s international security strategy, security assistance and defense trade – equated security cooperation with other regional partners, like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Lebanon, and Jordan, as components to Israeli QME, suggesting their security and partnership was a regional strategy for countering Iran. After specifically noting Iran’s preeminence as the chief shared security threat in the region and offering comments to reassert the U.S. commitment to Israeli QME, then-Assistant Secretary Shapiro makes the following comments relating the U.S. commitments to Arab partners to supporting Israeli QME:

Our QME considerations are not simply focused on our security assistance and defense sales to Israel, they extend to our decisions on defense cooperation with all other governments in the region. This means that as a matter of policy, we will not proceed with any release of military equipment or services that may pose a risk to allies or contribute to regional insecurity in the Middle East… But it is also important to note that our close relationships with countries in the region are critical to regional stability and Israel’s security. Our relationships with Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and many Gulf countries allow the United States to strongly advocate for peace and stability in the region.

He goes on to detail how each of the named countries was then cooperating with the U.S. to stabilize the region and advance perceived U.S. national security interests, adding how military aid like FMF, conditional assistance emphasizing peace with Israel, and enhanced Arab-Israeli security cooperation have ensured U.S. interests are preserved (Bernstein 2011).

In the recent developments between Israel, the U.A.E. and Bahrain, multiple Trump Administration officials (Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Presidential Advisor Jared Kushner, and President Trump, himself) have highlighted a willingness to offer the F-35 to the U.A.E. in the wake of its normalizing relations with Israel through the Abraham Accords. This comes after nearly three years of Emirati requests for the air platform only offered to Israel in the Middle East to date. Reports have suggested support from Israel, despite Netanyahu’s public concerns, with the prospect of Israeli manufacturing for future deliveries to the Emirates. In fact, some reporting claiming comments from unnamed Israeli defense figures suggests that Israel welcomes the transfer of the F-35s (along with enduring transfers between Israel and the U.A.E.) as disruptors of the power balance in the region to Israel’s favor (Egozi 2020).

Conclusion

Arms transfer is a tool states exercise in order to advance their foreign policy aims. Israel has long served as an ally of the U.S. in the Middle East – one undoubtedly with significant security challenges. The U.S. policy aimed at securing and maintaining Israel’s “Qualitative Military Edge,” as codified in the 2008 amendment to the AECA, aims to promote Israeli security in an Arab region that has historically met the Jewish state with hostility. The underlying strategy, however, is not as simple as fostering a foreign partner’s security for its own sake. So why, as of October 2020, has the U.S. government committed itself to ensuring Israel’s ability “to counter and defeat any credible conventional military threat,” as outlined in the 2008 amendment to the AECA? The U.S. interests in Israel’s materiel advantage are part of a deliberate strategy for countering the U.S.’s competitors in the region. Prior to forming this strategy into law, the U.S. pursued arms transfers to promote American influence against the Soviet Union. More recently, the same strategy serves as a counter for an increasingly belligerent Iran.

The operationalization of this strategy is a two-pronged effort. First, the U.S. establishes a strong partner in the Middle East, capable of projecting the U.S.’s strategic strength and influence through a cooperative and compliant Israel. This paper shows that this type of relationship has existed in increasing capacity since the establishment of Israel. Second, through an incentives-based arms transfer strategy with Arab states that are cold to Iranian activities, the U.S. can promote Arab-Israeli normalization and peace in exchange for supplying more advanced capabilities. This is in part structured upon the maintenance of Israeli security but is predicated upon a shared threat in Iran. Once again, this paper reveals that this strategy predates but is formally codified in the 2008 amendment to the AECA. Because of this, the emphasis on pure Israeli QME is reduced, allowing for increased materiel transfers across Arab partners, where Israeli security is guaranteed as a condition of the transfer. The result is a U.S.-armed and cooperative Arab-Israeli coalition built in contrast to Iran.

Indeed, in comparison to some periods of pre-2008 arms transfer values between the U.S. and Israel, the transfers since the amendment codified the Israeli QME certification have been somewhat flat. This supports findings that QME certification includes a multitude of factors beyond simple arms transfer values, like Israel’s own investment and, as argued herein, the security landscape and diplomatic relations between Israel and its Arab neighbors. More research may be conducted, however, around specific types of weapons platforms, similar to the review of the F-35 to the U.A.E., to determine if additional emphasis might be placed on the complexity of the systems the U.S. offers to its partners across the Middle East. Another area that may offer additional insights into how the U.S. calculates its arms transfer decisions in the region is the amount of military technology investment other (and particularly rival) states are placing in the region. As Russia and China continue to ascend as great power rivals to the U.S., understanding their national security interests in the Middle East could affect the U.S.’s strategy for continued and expanding partnership with Arab states.

Tables and Figures

Bibliography

Bahgat, Gawdat. 2017. “US-Iran relations under the Trump Administration.” Mediterranean Quarterly 28, no. 3: 93-111. https://doi.org/10.1215/10474552.

Bahgat, Gawdat and Robert Sharp. 2014. “Prospects for a New U.S. Strategic Orientation in the Middle East.” Mediterranean Quarterly 25, no. 3: 27-39. https://doi.org/10.1215/10474552-2772244.

Bernstein, Jarrod. 2011. “Ensuring Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge.” WhiteHouse.Gov, November 17, 2011. Accessed September 23, 2020. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2011/11/17/ensuring-israels-qualitative-military-edge.

Berrigan, Frida. 2009. “Made in the U.S.A.: American Military Aid to Israel.” Journal of Palestine Studies 38, no. 3 (Spring): 6-21. https://doi.org/jps.2009.XXXVIII.3.6.

Capaccio, Anthony. 2020. “UAE Submits to Buy F-35s From U.S. After Israel Deal.” Bloomberg, September 25, 2020. Accessed October 1, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-09-25/uae-submits-request-to-buy-f-35s-from-u-s-after-israel-deal.

Childs, Steven J. 2019. “Granting Security? U.S. Security Assistance Programs and Political Stability in the Greater Middle East and Africa.” The Journal of the Middle East and Africa 10, no. 2: 157-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520844.2019.1596649.

Cohen, Zachary, Hamdi Alkhshali, Kareem Khadder and Angela Dwan. 2020. “US drone strike ordered by Trump kills top Iranian commander in Baghdad.” CNN, January 4, 2020. Accessed October 1, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/01/02/middleeast/baghdad-airport-rockets/index.html.

Defense Security Cooperation Agency. n.d. “Security Assistance Management Manual Glossary: Arms Export Control Act.” Accessed October 1, 2020. https://www.samm.dsca.mil/glossary/arms-export-control-act-aeca.

Department of State. 2020. “Fact Sheet: U.S. Security Cooperation With Jordan.” Accessed September 23, 2020. https://www.state.gov/u-s-security-cooperation-with-jordan/.

DeYoung, Karen and Anne Gearan. 2020. “Israel signs deal establishing formal ties with two Arab states at the White House.” The Washington Post, September 23, 2020. Accessed September 23, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-israel-middle-east/2020/09/15/e4c2630a-f75c-11ea-a275-1a2c2d36e1f1_story.html.

Dougherty, James E and Robert L Pfaltzgraff, Jr. 2001. Contending Theories of International Relations: A Comprehensive Survey. New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Egozi, Aerie. 2020. “Israel Juggles Arms Exports as UAE Opening Ripples Across Mideast.” Breaking Defense, August 26, 2020. Accessed September 23, 2020. https://breakingdefense.com/2020/08/israel-juggles-arms-exports-as-uae-opening-ripples-across-mideast/.

Jervis, Robert. 2017. Perception and Misperception in International Relations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Keller, William W. and Janne E. Nolan. 2001. “Mortgaging Security for Economic Gain: U.S. Arms Policy in an Insecure World.” International Studies Perspectives 2, no. 2: 177-193. https://doi.org/10.1111/1528-3577.00048.

Lobell, Steven E. 2008. “The Second Face of American Security: The US-Jordan Free Trade Agreement as Security Policy.” Comparative Strategy 27, no. 1: 88-100. https://doi.org/10,1080/01495930701839795.

Mintz, Alex and Uk Heo. 2014. “Triads in International Relations: The Effect of Superpower Aid, Trade, and Arms Transfers on Conflict in the Middle East.” Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy 20, no. 3: 441-459. https://doi.org/10.1515/peps-2014-0019.

Neuman, Stephanie G. 2010. “Power, Influence, and Hierarchy: Defense Industries in a Unipolar World.” Defence and Peace Economics 21, no. 1: 105-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242690903105398.

Rodman, David. 2019. “Arms and influence: the American-Israeli relationship and the 1969-1970 War of Attrition.” Israel Affairs 25, no. 1: 26-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537121.2019.1554350.

Sanjian, Gregory S. 2003. “Arms Transfers, Military Balances, and Interstate Relations: Modeling Power Balance Versus Power Transition Linkages.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 47, no. 6 (December): 711-727. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002703258801.

Sislin, John. 1994. “Arms as Influence: The Determinants of Successful Influence.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 38, no. 4: 665-689.

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. n.d. “SIPRI Arms Transfer Database – Methodology.” Accessed September 30, 2020. https://www.sipri.org/databases/armstransfers/background.

Teeney, Al. 2010. “United States Government Benefits as a Result of Foreign Military Sales Programs.” The DISAM Journal of International Security Assistance Management (March 2010): 73-78.

Tominaga, Erika. 2015. “The failure in the search for peace: America’s 1968 sale of F-4 Phantoms to Israel and its policy towards Israel and Jordan.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 16: 303-327. https://doi.org/10.1093/irap/lcv021.

U.S. Code. n.d. “22 USC Ch. 29: Arms Control, §2776. Reports and certifications to Congress on military exports, (h) Certification requirement relating to Israel’s qualitative military edge.” Accessed October 2, 2020. https://www.uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title22/chater39&edition=prelim.

Wunderle, William and Andre Briere. 2008. “Augmenting Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge.” Middle East Quarterly15, no. 1: 49-58.

Yarhi-Milo, Keren, Alexander Lanoszka and Zack Cooper. 2016. “To Arm or to Ally?: The Patron’s Dilemma and the Strategic Logic of Arms Transfers and Alliances.” International Security 41, no. 2 (Fall): 90-139. https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00250.

Zilber, Neri. 2020. “Peace for Warplanes?” Foreign Policy, August 31, 2020. Accessed September 23, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/08/31/israel-uae-peace-deal-f-35-arms-sales-palestine/.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Deterrence and Ambiguity: Motivations behind Israel’s Nuclear Strategy

- The Puzzle of U.S. Foreign Policy Revision Regarding Iran’s Nuclear Program

- The Instrumentalization of Energy and Arms Sales in Russia’s Middle East Policy

- Jimmy Carter’s Liberalism: A Failed Revolution of U.S. Foreign Policy?

- ‘Almost Perfect’: The Bureaucratic Politics Model and U.S. Foreign Policy

- Shifting Hegemony: China’s Challenge to U.S. Hegemony During COVID-19