Malaysia is a multi-ethnic and multi-lingual nation. This is due to factors such as the powerful role of the Malay language in Southeast Asia, migration, colonial rule, and globalization. Because of these characteristics, Malaysia often faces language conflicts. Historically, Malaysia has experienced inter-ethnic language conflicts. Language policy is often considered irrelevant to international relations, but it is highly relevant to the study of international relations because external factors have a significant impact on the language situation within a country. Language policy includes invisible and informal language management as well as tangible government laws and regulations.

There are two main research questions in this study: How does rapidly increasing globalization (and the rise of English) affect Malaysian language policy? And how do ethnic nationalist sentiments influence Malaysian language policy? To address these research questions, questionnaires were conducted for Malaysian citizens, and 120 people participated. In addition, six Malaysians from different ethnic backgrounds were selected from the questionnaire respondents and interviewed to obtain a better understanding of public perspectives. In addition to these two methods, Malaysian news articles (a total of 161 articles) were analyzed to gain a broader view of Malaysian attitudes towards the government’s English policy and vernacular schools that use Chinese and Tamil as the primary languages of instruction.

This paper is a summary of a bachelor thesis submitted as an article to E-International Relations. In order to comply with the submission requirements, several adjustments, summaries, and omissions have been made. As a result, this paper contains only the analysis and research findings from the questionnaires and interviews, and the names of the interviewees remain anonymous. It should also be noted that this research has limitations, particularly in terms of the representativeness of the questionnaire respondents. The majority of the 120 respondents were Chinese and Malays. It was not possible to obtain an equivalent number of Indian respondents. I should also mention the selection bias, as the participants for the questionnaire and interviews were selected from those who spoke English in their daily lives. This criteria was important to minimize misunderstandings between them and the author during the research. Therefore, another limitation is the use of English. Although all participants claimed to speak their ethnic language at home, I conducted the interviews in English. However, the misunderstandings caused by language differences are likely to be minor, as all the interviewees stated that they use English on a daily basis, such as at school or at work.

The Impact of Globalization on Language Policy

In order to assess the impact of globalization on a country’s language policy, it is first necessary to understand what globalization is. According to Robertson and White (2007), globalization has three dimensions: economic, political, and cultural. Looking at globalization from a broader perspective, globalization is a process in which the world becomes increasingly homogeneous. In other words, globalization is the increase in global interconnectedness. However, the fact that the world is becoming one poses the question, “On what basis is the world becoming one?” The answer to this question is that globalization refers to the process by which the world becomes unified as a result of the expansion of Western culture, that is, the growth of world Westernization, as it often creates asymmetric economic dependencies between states, such as unilateral resource management and unequal distribution of profits (Mufwene, 2005). If globalization is defined as the unification of the world through the expansion of Western culture, it is natural to focus on the role of English when analyzing the relationship between globalization and language policy.

As English spreads around the world, other languages are disappearing. According to Mufwene (2005, p.20), English is the “killer language.” For example, during the colonial period in Africa, local people spoke Creole (a mixed language with English), and in isolated plantation societies, they had little opportunity to speak their native languages. Such consequences of the inflow of English as a result of the expansion of Western culture were similar in Malaysia, although, in colonized Malaysia, English was spoken only by foreigners such as the British, Chinese, and a few elite Malays. Safran (2004) also argues that while the Internet, a major contributor to globalization, is helping to preserve minority languages by facilitating cross-border communication between isolated and decentralized language communities, many languages in the world are struggling to survive in the age of globalization (Kittelstad, n.d.; Lamba & Malhotra, 2009).

Even if a local language disappears as a result of the spread of English, the function of English is so significant that the spread of English can have a positive influence on countries. Singapore’s bilingual policy is a case in point. Since its independence from the Federation of Malaysia, Singapore has adopted a bilingual policy, and Singaporean students are expected to learn one of three ethnic languages in addition to English. Singapore gained independence from Malaysia in 1965 as a result of a disagreement over Malaysia’s language policy, which has focused on protecting the Malay language since independence (Rappa & Wee, 2006). Because Singapore was small and had few natural resources, the expansion of the Singaporean economy after independence depended on foreign investments and multinational corporations. As a result, English has become increasingly important in Singapore as a symbol of economic progress. Although Singapore, like Malaysia, is home to various ethnic groups and languages, Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore aimed to promote national growth and unity by enabling these various ethnic groups to interact in English. Thus, English serves the dual purpose of assisting nations in their economic development while also serving as a language that promotes ethnic unity in multi-ethnic nations (Rappa & Wee, 2006; Silver, 2005).

Given the importance of English for economic development and inter-ethnic communication, the adoption of English seems a logical choice for countries in this increasingly globalized world. According to Safran (2004), minority groups prefer to give up on their own languages in favor of other dominant languages that provide them with superior economic, social, and political benefits. It is reasonable enough for language minorities to do so because language policies categorize and divide different groups of people who speak different languages and assign them different social statuses (Tollefson, 1991). The same is true of nations. It makes sense for them to promote the use of English within their countries in order to increase national competitiveness and economic advantage.

Languages and National/Ethnic Identity

Language, according to Spolsky (1999), is a crucial instrument for defining people’s identities. A language can reveal to others one’s nationality, race, gender, level of education, age, occupation, and other personal information. Therefore, he believes that ethnic issues are often intertwined with languages. Even when ethnic minorities are persecuted because of external or internal threats, they can still maintain their identity by expressing themselves in their language and uniting as one. On the other hand, governments or opposing ethnic groups may also use language policies to restrict the use of minority languages for various reasons. In such cases, minority people’s fear of losing their languages would be equivalent to their fear of losing their ethnicity because language symbolizes their identity of who they are. Ethnic movements would arise over language issues, and hostilities among different ethnic groups are linked to disputes over different languages. Language preservation or revival, according to Spolsky (1999), is an essential component of an ethnic movement.

The May 13 riots in Malaysia in 1969 demonstrate the relationship between ethnic issues and languages. They were the culmination of Malay-Chinese conflicts that erupted during the 1969 general election when the Chinese-majority opposition Democratic Action Party (DAP) performed well in Selangor. The results of the 1969 election fueled Malay fears of losing their supremacy and created the spectacle of minority groups possibly overtaking the Malays. As a result, racial tensions between Malays and non-Malays escalated during the celebratory parade, culminating in widespread and violent rioting in the streets of Kuala Lumpur, with shops and houses being torched. While the final death toll was estimated to be 196, Western media reported that the total number of deaths, mostly Chinese, could have been closer to 600 (Sukumaran, 2019). There had been political and social unrest among different ethnic groups for years, but the cause of the May 13 riots was not simply their disagreements but also struggles over language rights. It then escalated further. In the aftermath of the riots, efforts to develop Malay as the sole national language and to restrict Chinese and Tamil have intensified.

History and Progress of Malaysian Language Policy

Malaysia’s language policy is more complex than that of the other parts of South and East Asia, such as Vietnam and Thailand, which are multilingual and multiethnic but have mostly indigenous populations, or monolingual and monoethnic South Korea and Japan, because Malaysia is a multilingual and multiethnic country where indigenous and foreign ethnic groups, such as Chinese and Indians, coexist (Chu & Le, 2020; Gill, 2014). Mukherjee and David (2011) argue that language policy is problematic in multilingual and multiethnic developing countries because part of national unity, which leads to economic development, is the result of successful language policy. Therefore, understanding the history and development of Malaysian language policy requires a comprehensive grasp of Malaysia’s complex historical backgrounds, cultures, and ethnic concerns.

Portugal was the first to conquer Malaysia, whose rule over Malaysia began in 1511. After Portugal, the Dutch ruled Malaysia from 1641 and the British from 1824 (Drabble, 2000; Steinhauer, 2004). Each had different methods of warfare, control of the military and civilian population, and even different language policies. Although the development of the Malay language continued under Dutch rule, it was British rule that had a major impact on current Malaysia’s language policy (Rappa & Wee, 2006). There are two main reasons why the British rule in Malaysia had the greatest impact on Malaysia’s language policy.

The first reason is that the British brought a large number of immigrants to the Malay Peninsula from India for labor and from China for tin mining. According to Shamsul (2004) and Steinhauer (2004), the British government was able to use the vast Malay land for mining because the land was under state control. At the same time, they converted Malay forests into plantations and imported many Indian laborers to work on the plantations. The British also developed a new land system known as Tenure, which turned agricultural land into a commercial product. This meant that land acquired monetary value and could be freely bought or sold within the limitations of the colonial administration. Although Mohamad (2008) claims that Chinese economic activities in urban areas existed before the arrival of the British, the new land system encouraged Chinese businessmen to settle in cities to conduct their businesses. According to Steinhauer (2004), it was not only the land policy that encouraged greater Chinese immigration but also the discovery of the mining industry, which significantly changed the ethnic composition of Malaysia.

Mohamad (2008) argues that the Chinese and Indians believe that their work in plantations and mining has supported Malaysia’s growth. However, he believes that these migrants did not come to develop Malaysia but rather to exploit it for their own benefit and that such developments did not bring positive benefits to most Malays. Mohamad (2008) further argues that the Chinese became richer in urban areas because they were protected by the British. As mentioned above, Chinese traders existed in the Malay Peninsula before the arrival of the British. Although they could not be integrated religiously, they were useful to the British authorities because of their understanding of local customs and their ability to communicate in Malay. The ethnic diversification of Malaysia by the British is also explained by Embong (2002, p. 45). According to him, the immigration of Chinese and Indians to the Malay Peninsula lasted from around the mid-19th century to 1930, resulting in “transforming the basically mono-ethnic indigenous society into a plural society comprised of indigenous people and immigrants.” It is arguable whether Malaya (a federation of the Malay Peninsula under British control) was a monoethnic indigenous society, as there were other ethnic groups, such as Indians, Arabs, Indonesians, and Chinese, before the British arrival. However, it is true that the British radically changed the ethnic composition of Malaysia by bringing in more immigrants, and it is understandable that when the ethnic composition changes, language becomes an issue, and a language policy becomes necessary.

As previously stated, in the British-controlled Malay Peninsula, Chinese people lived in urban areas while Malays were forced to relocate to rural regions. In addition, while the Chinese were employed in commerce and mining, the Indians were mobilized for plantation labor. This ethnic segregation was not limited to housing and employment; the British also segregated education and administrative policies along racial lines. This ethnic division by the British is the second reason why the British had a huge impact on Malaysia’s language policy. Because each ethnic group speaks a different language, ethnic discrimination policies are heavily influenced by language. As a result, the British policy of separation can be reformulated as a policy of language discrimination. The British initially did not accept immigrants as citizens, and the only legitimate citizens for the British were the Malays who were indigenous to the country. Any decision or change in the Malay Peninsula required the consent of the Malays, while only consultation with the Chinese was required (Mohamad, 2008). Thus, citizenship rights were not equal but discriminatory based on ethnicity throughout the early British period.

This changed with the end of the Second World War and the restoration of British control. After the war, the British wanted to grant full and equal citizenship to the Chinese and Indians. This was due to the British attempts to assimilate the immigrant community into the Malays, which led to disputes between the Malay and Chinese communities, making the relationship between the two groups an issue that now needs to be addressed at a national level (Ang, 2009; Jones, 2014; Mohamad, 2008). Mohamad (2008) argues that if citizenship is to be extended, it should be done gradually, starting with a small number of immigrants. They must also adopt Malay culture. Before the Second World War, the Malays only faced immigration problems. However, with the Malayan Union’s proposal of full citizenship for immigrants, they also experienced citizenship issues (Mohamad, 2008). This was not just a problem between the Malays and Chinese. By shifting from a policy of Malay preference (recognizing only Malays as citizens) before the Second World War to a more accommodating attitude towards immigrants after the war, the British made enemies of both Malays and non-Malays, including the Chinese and Indians (Jones, 2014).

Apart from inequalities in citizenship, the British also divided education along language and ethnic lines, establishing four types of schools: Malay, English, Chinese, and Tamil schools. Initially, the British administration favored Malay and English schools. Throughout the 1930s, it was possible for students to transfer from a Malay primary school to an English primary school after two years of special Malay courses, but Chinese and Tamil primary school students were not allowed to transfer to an English school. In addition, Malay and English primary school students had options other than secondary school, such as going to medical school, but this was not possible for Chinese and Tamil primary school students (Koh, 2017). This was largely because the British recognized Malay as the sole national language, while Chinese and Tamil were considered immigrant languages.

The gap between English and Malay, however, was not insignificant. According to Guan (2007), Malay remained a national language, but its treatment was only marginally better than that of other languages, as almost all government documents and contacts were made in English. Steinhauer (2004) also noted that the British believed that English education was unsuitable for the Malay people. There are two possible reasons for this. Firstly, English education was only available to the British upper class and the wealthy (Omar, 1985). The British also adopted a “dual track strategy” by first educating only a few elite Malays in English and then educating the rest of the Malay people in Malay (Guan, 2007, p. 121). As a result, only a small number of Malays in the country had access to English education, while the majority of Malays did not have the opportunity to be educated in English (Mohamad, 2008; Yang & Ishak, 2012). The second reason was that the British were concerned about the prospect of a Malay insurgency. Having witnessed the uprisings of the local population in British India, they feared that if more Malays learned English, Malaysia might be able to challenge British control in the same way as India (Guan, 2007; Mohamad, 2008). These are two possible explanations for why the British did not prioritize English education for the Malays.

The British not only separated its educational system by language but also differentiated the superiority of languages. In the education system, Malay’s supremacy as the single national language over Chinese and Tamil was merely nominal. Instead, English was extremely important, and an individual’s English proficiency determined his or her career opportunities (Rappa & Wee, 2006; Koh, 2017). As mentioned earlier, in addition to the fact that English education was exclusively available to prestigious groups, Christian missionary schools also provided English education, but only in non-Muslim areas. Thus, only the Chinese and Indians were able to learn English in Christian schools (Guan, 2007). Language-based inequalities were also evident in government support for school administration and maintenance. The British government provided financial support to Malay and English schools, while Chinese schools did not receive governmental support. As a result, Chinese schools had no choice but to fund themselves while coexisting with Malay and English schools (Ang, 2009; Guan, 2007).

The British nearly eliminated multiethnic interactions by having Malays, Chinese, and Indians live in different places and attend different schools separated by language and ethnicity. They also prevented interethnic unity and communication by categorizing people and providing different social statuses based on languages, such as English as the dominant language, Malay as the nominally national language, and Chinese and Tamil as immigrant languages.

After Independence: Malaysian Language Policy and Nationalism

Language policy plays a balancing role between national identity and modernity. Therefore, language policy has been essential for post-independence Southeast Asian states in maintaining their own identity and asserting sovereignty in a rapidly changing political environment as a result of independence from Western powers. This means that Malaysia experienced a surge of nationalism after independence, necessitating the implementation of language policies to unify the country. While the focus of earlier sections was on the balancing act between national identity and modernization, such as development, Malaysia, immediately after independence, was faced with the need to create a single national language to deal with the multiethnic domestic environment that had been created mainly during the colonial period. Modernization in this context, therefore, refers to Malaysia’s multiethnic and multilingual condition. It also encompasses the relationship between the Chinese minorities in Malaysia and the growing influence of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), as well as the function of English as a global language.

Nationalism is the fundamental driving factor behind the restoration of traditional solidarity that has been undermined by colonization and other external influences (Anderson, 2006). Safran (2004, p. 1) claimed that “language is a marker of ethnic identity; a vehicle for expressing a distinct culture; a source of national cohesion; and an instrument for building political community.” Thus, having a common language is an important factor in the process of unifying a country. However, it is not uncommon for former colonial nations to become multilingual and multiethnic under the influence of colonization (Gill, 2014). Also, the languages that came from other countries during the colonial era, the languages of the colonial nations, and the local languages have different cultures and histories (Anderson, 2006). As a result, former colonial states face ethnic issues when attempting to gain independence and unify the country, as there would be conflicts in discussing which language should be the national language in such a multilingual society. According to Anderson (2006, pp. 36, 198-199), the “Sumpah Pemuda” (the Youth Pledge) was proclaimed in Indonesia in 1928 by Indonesian nationalists, which promoted three main ideas: “One country, One Flag, One Language.” But in Southeast Asian countries that have become multilingual nations due to colonial control, what is the “One language” that can unite and symbolize a nation?

Malaysia can promote nationalism by making Malay the sole national language, but this will come at the expense of Chinese, Tamil, and other minority languages, leading to inter-ethnic conflict. Although it may seem that a bilingual policy of English and mother languages, such as the Singapore model, can achieve both ethnic identity and national unity, in reality, Singapore is almost a monolingual English nation because most of the administration is conducted exclusively in English (Omar, 1985). Thus, what kind of language policy should post-independence Malaysia adopt in order to achieve peaceful nation-building?

Malaysia has a strong nationalist sentiment that is Malay-centric, such as the belief that Malaysia is a country of Malays and should be united with the Malay language. This is most evident in the book Malay Dilemma by Malaysia’s 4th and 7th Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad (2008). Although his book has already been acknowledged in other sections of this research, I should emphasize that the main message of his book is about Malay-centric nationalism. He claims that only the Malays are the legitimate owners of Malaysia and that other races, such as the Chinese and Indians, can only be recognized as citizens if the Malays agree (p. 161). Not only for immigrants but also for other indigenous groups, he claims that Malaysia belongs to the Malay people, even if other groups had lived on the Malay Peninsula before the Malays because the Malays were the definitive people who established the first effective government (pp. 161-164).

He also considers it nonsensical for the Chinese and Indians to seek equal rights with the Malays or to claim the nation as their own because this ignores “all precedents and facts of history” (p. 167). Since he reiterates Chinese economic supremacy, the term “precedents and facts of history” could include Chinese economic dominance in Malaysia since British control. He also claims that the Malays have no alternative place to return to, while the Chinese and Indians may live in their home countries. As a result, he believes that only the Malays should claim Malaysia as their own nation. It is then also possible to conclude that all his views are expressions of the exclusive linguistic nationalism described by Saifullah (2017). Malaysia did not seek solidarity by balancing a multilingual society after independence. Instead, it sought national unity by suppressing immigrant languages such as Chinese and Tamil and supporting Malay dominance.

According to Safran (2004, p. 7), a language must be linked to the education system in order for it to play a “nationalizing” role because mass mobilization is more effective when the language spoken by the common people is adapted rather than the language used by a few elites. Therefore, Malay nationalism placed great importance on language education policy. The Abdul Razak Committee on Education was established in 1955, and the Razak Education Report recommended that the national education system should be created in Malay as the national language in 1956. Furthermore, the role of Malay (and English as a second language) was also emphasized in the 1960 Talib Report (Guan, 2007; Rappa & Wee, 2006), the 1961 Education Act (Ang, 2009; Guan, 2007; Rappa & Wee, 2006) and the 1963 National Language Act (Rappa & Wee, 2006; Yang & Ishak, 2012), while Chinese and Tamil schools were increasingly suppressed. The Talib Report described the establishment of a Malay-only education system as a long-term plan, that is, the gradual abolition of Chinese schools through restrictions on government aid to Chinese schools or recommendations to conduct examinations only in Malay (Guan, 2007). As a result, there was growing concern about the future education system for the Chinese community.

Furthermore, the New Economic Policy was introduced after the May 13 riots in 1969, and an ethnic quota system for school enrolment was introduced, also known as the Bumiputera Policy. During this period, Chinese students were given fewer educational opportunities than Malay students (Ang, 2009; Guan, 2007; Rappa & Wee, 2006). In response, the Chinese community attempted to establish the Merdeka University with Chinese as the medium of instruction, but this was rejected by the Malay government (Ang, 2009; Guan, 2007).

English has remained the second most important language in the Malaysian education system since independence. However, the process of gradually phasing out English as the medium of instruction in schools began in the 1970s, and Malay education was promoted more strongly (Guan, 2007; Omar, 1985). Despite Malaysia’s emphasis on Malay education, the importance of English, as opposed to Chinese and Tamil, has gradually been emphasized. For example, in 2003, Mahathir Mohamad declared a policy of teaching math and science in English as a result of rising unemployment due to the lack of English skills among graduates. However, this policy was contested by both the Malays and the Chinese, who felt that their ethnic identities and languages were threatened by English. As a result, the government announced its removal in 2009 (Guan, 2007; Yang & Ishak, 2012). Despite Mahathir Mohamad’s declared desire to reintroduce a policy called Pengajaran dan Pembelajaran Sains dan Matematik Dalam Bahasa Inggeris (PPSMI) in 2020, the Ministry of Education announced that there would be no such reintroduction (Hassan, 2020; Sivanandam et al., 2020).

Malaysia’s language education policy has a strong interaction with Malay-centric nationalism, as promoting Malay education to the exclusion of other languages is itself a form of nationalism that also has the potential to promote further national solidarity. Nevertheless, there are ongoing tensions with other languages in Malaysia, as evidenced by the Chinese Education Movement in 1952, the May 13 riots, and various attempts by the Chinese community to build their universities. Malaysian language education policy must also strike a balance between English as a language of survival in the globalized world and Malay as a means of preserving national identity.

Analysis—The Impacts of Globalization on Malaysian Language Policy

Increasing Importance of English

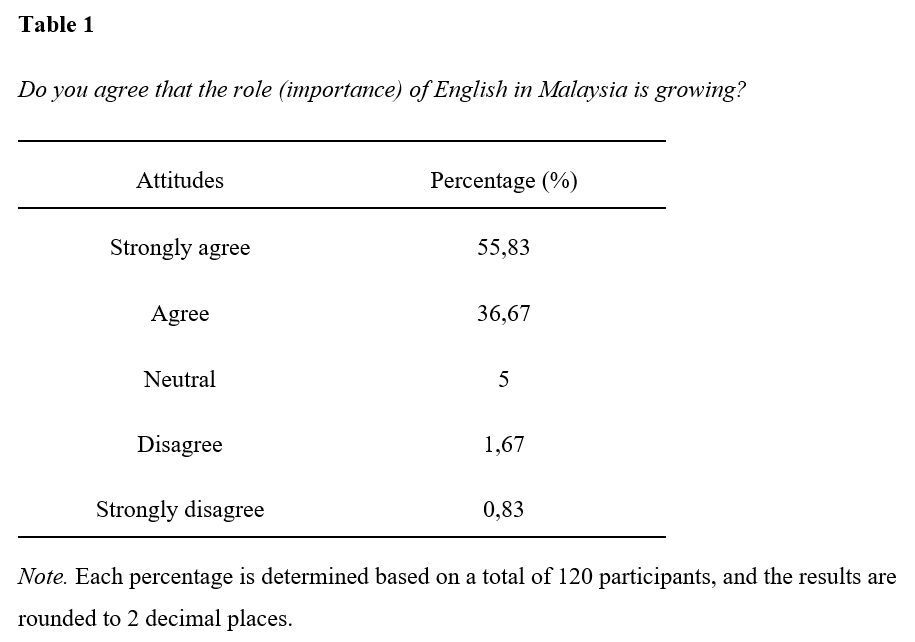

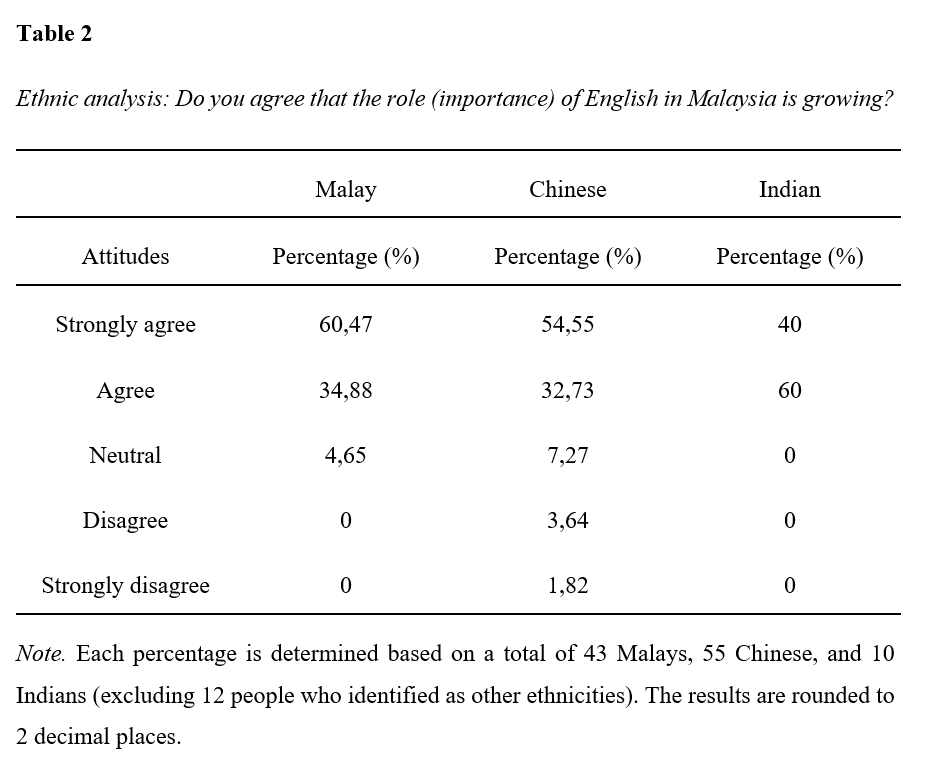

The Malaysian government considered English as an official language for a provisional period after independence from the British colony but is now pushing for Malay to be the sole national language. However, even under these conditions, the rapid globalization of the world has shown the importance of English in Malaysia. Malay is the national language, but English is also the second most important language in Malaysia. It is no exaggeration to say that English is not a foreign language to Malaysians and that many of them consider English to be the “second language” of the country. Therefore, the first claim here is that English is becoming increasingly important in Malaysia as a result of globalization, and the government needs to recognize the significance of embracing English alongside the national language. The findings of the two questionnaires I conducted are referred to in support of this statement (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1 shows the results of a questionnaire asking whether the role (importance) of English is increasing in Malaysia, and Table 2 shows the results of the same question classified by the ethnicity of the participants. About 56% of all respondents answered “strongly agree” that English is becoming more important in Malaysia, which is more than half of all respondents. In addition, about 37% of respondents said they “agree” with the question. When these two responses are combined, it can be seen that those who “strongly agree” or “agree” that English is becoming more important in Malaysia make up about 93% of all respondents. As Table 2 also shows, people in all three ethnic groups, regardless of their ethnicity, recognize the growing importance of English. Thus, it appears that the majority of Malaysians believe that the importance of English is increasing in the country. However, it is also worth noting that while none of the Malays and Indians chose “disagree” or “strongly disagree” on this question, some Chinese believe that the importance and role of English has not increased in Malaysia.

One of the interviewees (a boy of Chinese ethnicity) said that there are three large Chinese groups in Malaysian Chinese society. The first group consists of those who were born in an independent Chinese community and attend only Chinese schools. They, therefore, have little interaction with other ethnic groups. These Chinese do not mix with Malays and often do not speak Malay or even English. The second group consists of people who have little proficiency in Chinese because their parents do not speak Chinese. Therefore, they often attend Malay schools instead of Chinese schools and are deeply integrated with other ethnic groups. The third group consists of people who are moderately mixed with Malays and study Chinese alongside other languages, such as Malay and English. There is little interaction between these three Chinese communities, and they have difficulty communicating with each other, even among fellow Chinese. He said he sees himself in the middle, the third group.

Thus, people like the first Chinese group he mentioned are unlikely to recognize the growing importance of English in Malaysia. For them, their language is all that matters, whether or not there is globalization. The results of this questionnaire (the fact that only Chinese people chose “disagree” or “strongly disagree” with this question) can make us realize that, as the interviewee said, there are still Chinese people in Malaysia who belong to the first group who speak only Chinese, and their presence has a huge impact on Malaysia’s language policy.

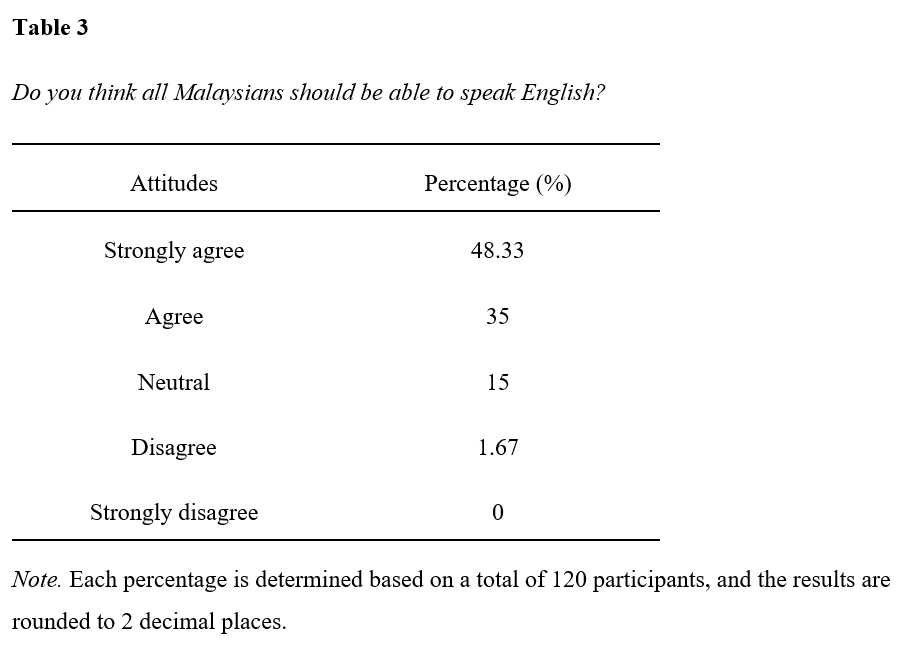

Not only do most Malaysians, with the exception of a few Chinese, recognize the growing importance of English, but many of them also believe that all Malaysians should be able to speak English. The findings of the relevant questionnaire are shown in Table 3.

Table 3 shows the results of a questionnaire in which participants were asked whether they think all Malaysians should be able to speak English. About 83% of all participants “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that all Malaysians should be able to speak English. Thus, Malaysians are aware of the need to learn English due to the increasing importance of English in the country.

The increasing importance of English in Malaysia and Malaysians’ perception of English as a necessary skill was also observed in the interviews. All six interviewees said that they use a combination of English and Malay (or their own ethnic language) on a daily basis. They also claimed that they use different languages depending on where they are and what they are doing, with English being commonly used in large cities such as Kuala Lumpur and in government offices and ethnic languages such as Malay, Chinese, and Tamil being used at home. One interviewee (a girl of Malay ethnicity) noted that using a combination of English and Malay is “a big part of our life,” depending on the location and situation. Thus, Malaysians use English in their daily lives, and English is often combined with their own ethnic languages, which may be a symbol of the increasing importance of English in Malaysia and the growing demand for English skills among Malaysians.

Room for Improvement in the Government’s English Policy

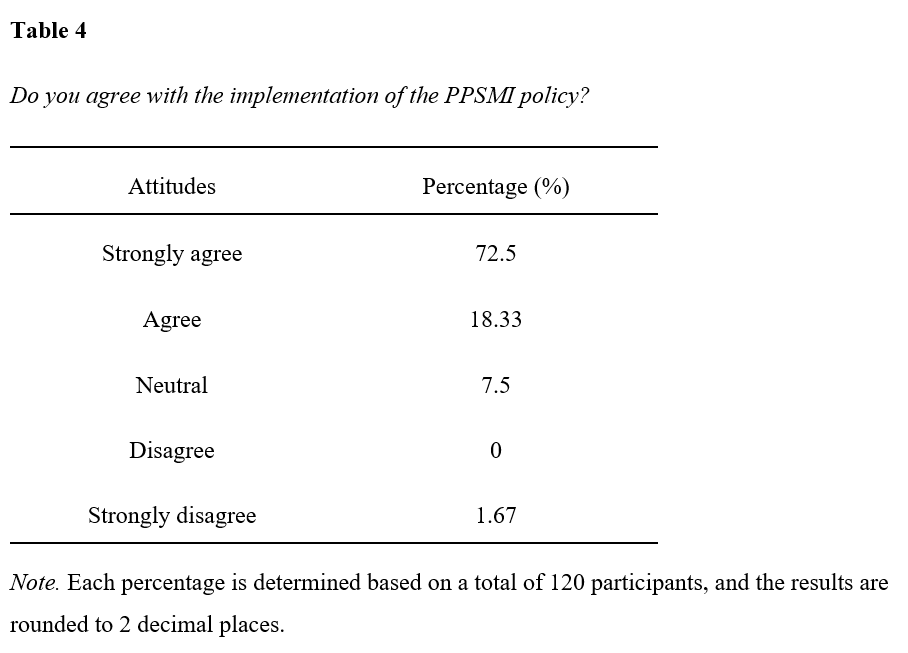

With the growing importance of English in Malaysia as a result of globalization, Malaysians encourage the government to implement policies that would enable more people to become English proficient. Thus, the second argument about the impact of globalization on Malaysian language policy is that Malaysians support the government’s initiatives to improve people’s English skills. The Malaysian government’s most representative English policy is the Pengajaran dan Pembelajaran Sains dan Matematik Dalam Bahasa Inggeris/ Teaching and Learning of Science and Mathematics in English (PPSMI policy).

The PPSMI policy, which requires mathematics and science subjects to be taught in English instead of Malay, can improve students’ English proficiency. However, the policy was abolished in 2009 due to opposition from nationalists from both Malay and minority ethnic groups (Guan, 2007; Yang & Ishak, 2012). Some believe that the PPSMI policy is detrimental to the status of their languages. In other words, some are concerned that the PPSMI policy may deprive students of the opportunity to acquire Malay, Chinese, or Tamil skills by forcing them to take classes in English. However, this research found that only a small number of Malaysians are actually unhappy with the PPSMI policy, while the majority are in favor of it (Table 4).

Table 4 shows the results of a questionnaire asking people’s opinions on the implementation of the PPSMI policy. According to Table 4, many Malaysians support the implementation of the policy. About 73% of all respondents answered that they “strongly agree” with the implementation of the policy, while 18% answered that they simply “agree.” Combining these two responses means that more than 90% of all respondents “strongly agree” or “agree” with the implementation of the PPSMI policy. Only two respondents opposed the implementation of the policy, and both were of Indian ethnicity. However, these results show that the majority of Malaysians are supportive and would welcome the implementation of the policy. Such supportive attitudes towards the PPSMI policy were further observed throughout the interviews. All interviewees expressed their support for the PPSMI policy and believed that studying some subjects in English would open up more opportunities for students in the future.

On the other hand, they also identified problems with the implementation of the PPSMI policy. The most serious problem they have with the PPSMI policy is that the government has not adequately planned the implementation of the policy. According to the interviewees (a Malay girl and a Chinese boy), the sudden implementation or withdrawal of such a government policy is a major problem. Students and teachers would feel confused if the Malaysian government unexpectedly decided to implement the PPSMI policy without any preparation or suddenly stopped enforcing the policy. Although the PPSMI policy is a good effort to improve people’s English skills and contribute to Malaysia’s overall growth, the PPSMI policy has never been effective due to unplanned and repeated sudden changes in initiatives. They feel that the Malaysian government only wants to show that they are doing something, but the government’s current policies are not fruitful because they have failed to effectively design and implement initiatives to improve people’s English proficiency.

In addition, as one interviewee (a Malay girl) stated in her interview, the implementation of the PPSMI policy should be considered in a long-term plan and implemented gradually over time. For example, a sudden change in language learning from high school, as happened in the earlier implementation of the PPSMI policy, can be very difficult for students. If policies such as teaching some subjects in English are to be implemented through the PPSMI policy and similar initiatives, the Malaysian government should start transactional processes from a younger age (e.g., primary school or kindergarten).

Irreplaceable Status of the Malay Language

The importance of English in Malaysia is increasing as a result of rapid globalization, and many Malaysians are becoming more aware of the value of acquiring English skills. It is also evident that the general Malaysian population supports the government’s English policy to improve their English skills. However, as English continues to grow in importance in Malaysia, the question arises as to whether English will eventually replace Malay. Will Malay’s status as Malaysia’s national language be challenged as the use of English becomes more widespread in the country? In Japan, for example, I find that people have very strong nationalistic feelings, and many have an absolute attachment to the Japanese language, such as “If you are Japanese, you should use Japanese.” When I interviewed my friends and family, they said that they feel that the value of the Japanese language may be forced to decline if the number of Japanese who speak English increases. They also told me that they do not want that to happen.

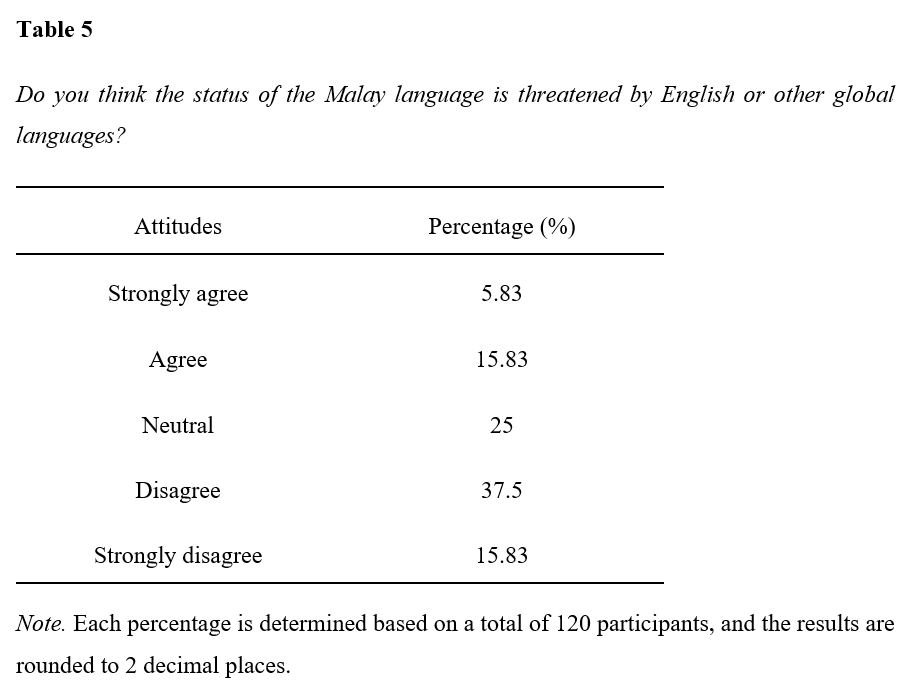

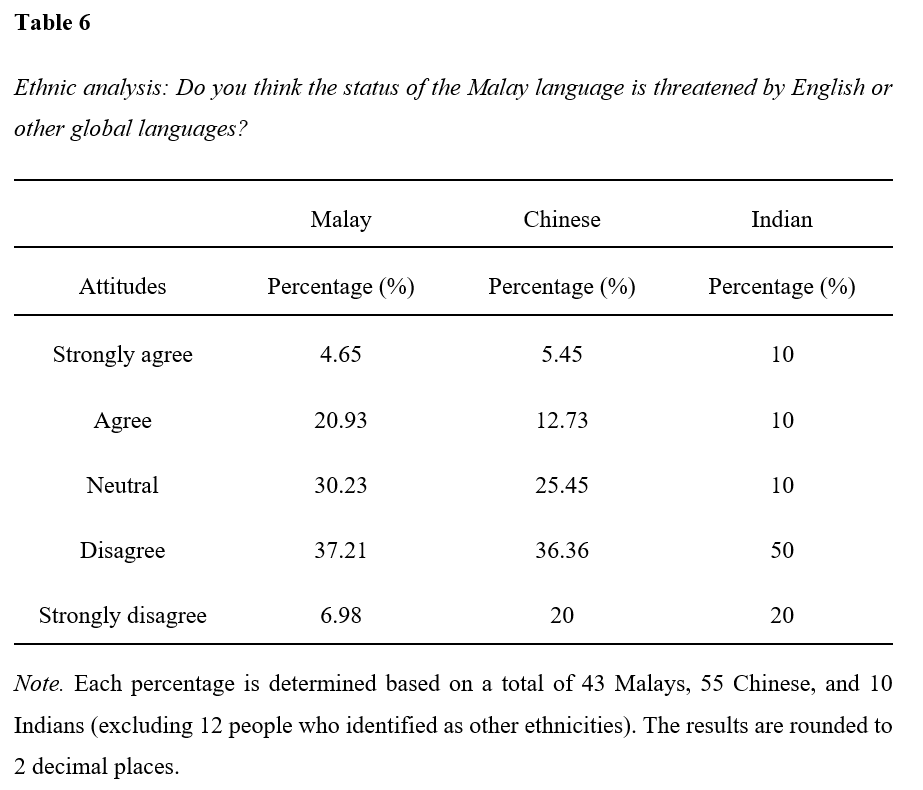

Thus, as more people feel that English is becoming a more important language in Malaysia, do Malaysians, like the Japanese I interviewed, feel that English is replacing Malay as their national language? The answer from this research is that English cannot be a language that replaces the role of Malay for a while. To support this third claim about the impact of globalization on Malaysian language policy, the findings of a relevant questionnaire will be referred to first (Tables 5 and 6).

Table 5 shows the results of a questionnaire in which participants were asked whether they believe that English is threatening the status of Malay, and Table 6 shows the results of the same question broken down by the ethnicity of the respondents. According to Table 5, “disagree” was the most common response to this question among all participants, with about 38% of all participants choosing this response. The second most common response was “neutral,” chosen by 25% of all participants. On the other hand, about 16% of all respondents answered “agree,” and about 6% of all respondents answered “strongly agree” to this question. Combining these two responses, this means that about 22% of the participants agreed that “English undermines the status of Malay.”

On the other hand, about 16% of all respondents answered “strongly disagree” with this question. When this answer is combined with the 38% of respondents who “disagreed,” it means that more than half of Malaysians believe that “English is not a threat to the current status of Malay.” As Table 6 also shows, it is clear that there is little variation in the pattern of responses across different ethnic backgrounds. The interviews helped to understand this further, and three factors were found to support this claim.

The first is that the Malay people, whose mother tongue is Malay, are the ethnic majority in Malaysia. Therefore, it is unlikely that Malay will be phased out in Malaysia. Two interviewees (both girls of Malay ethnicity) mentioned that they are aware that in today’s Malaysia, some young Malaysians (even Malays) do not speak Malay fluently. One reason for this is that Malaysian parents often focus solely on their children’s English education. As a result, even though they are Malay, these children sometimes speak English better than Malay. Despite this, interviewees also said that they still recognize the importance of Malaysians learning English. It would be possible for two languages, English and Malay, to coexist if English skills could be acquired while maintaining Malay as the national language rather than forcing Malay out so that people could acquire English skills. As long as the Malays remain the majority of Malaysia’s population, English and Malay may become more integrated, but the status of Malay will not be threatened by English.

Secondly, a story like “English is replacing the role of Malay” is simply a political tactic used by politicians and some extremists to keep people away from English. Keeping English away from people can directly lead to a focus on other languages, such as Malay, Chinese, and Tamil. And such a tactic also makes it easier for politicians and right-wing groups to unite Malaysian citizens. Slogans such as “English is dangerous” are just a political tool for them to use to successfully lead the people in the direction they want them to follow.

Finally, no matter how popular English becomes in Malaysia or what initiatives are taken to promote it, every student in every school will continue to learn Malay. Unlike the other languages (Chinese and Tamil), Malay is the only official and national language of Malaysia. Therefore, all children start learning Malay in kindergarten and continue to learn it in secondary school, as Malay language classes are compulsory in all types of schools. Therefore, as long as Malay is compulsory in schools, English will not threaten the status of Malay.

Given these facts, it is clear that English is not only a foreign language in Malaysia but also the second language of the country. Many Malaysians believe that English is a highly important language in this globalized world. Therefore, the Malaysian government must effectively implement policies that deal with English (such as the PPSMI policy), which requires long-term goals and proper planning. It is also important to note that improving the English proficiency of Malaysians through government language policies does not necessarily mean displacing the role of Malay as the national language.

Analysis—The Impacts of Ethnic Identity on Malaysian Language Policy

Ethnic Nationalism Embraces Multilingualism

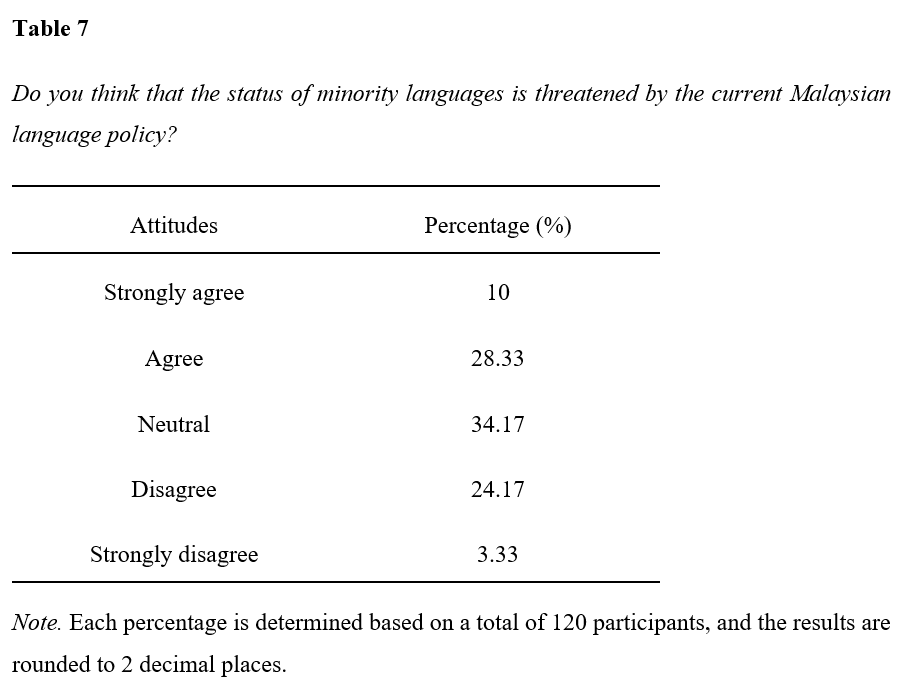

After gaining independence from British colonization, Malaysia made great efforts to unite the country. One of these efforts was to integrate different ethnic groups through a language policy that established Malay as the sole national language. Some Malays have strong pro-Malay sentiments, as highlighted by Mahathir Mohamad (2008). They often favor Malays over other ethnic groups and are enthusiastic about maintaining Malay as Malaysia’s sole national language. According to these people, only Malays are the official owners of Malaysia. However, this tendency also applies to ethnic minorities such as the Chinese and Indians. Some Chinese and Indians have strong ethnic nationalism, such as pro-Chinese and pro-Indian sentiments. This section focuses on how ethnic nationalist attitudes affect Malaysian language policy. The first argument is that ethnic minorities fear that Malaysia’s existing language policy will jeopardize the status of their languages, but ethnic nationalism does not solely seek to protect the language of one’s own ethnicity. First, the results of a relevant questionnaire are analyzed to determine how Malaysia’s current language policy affects the status of minority languages (Table 7).

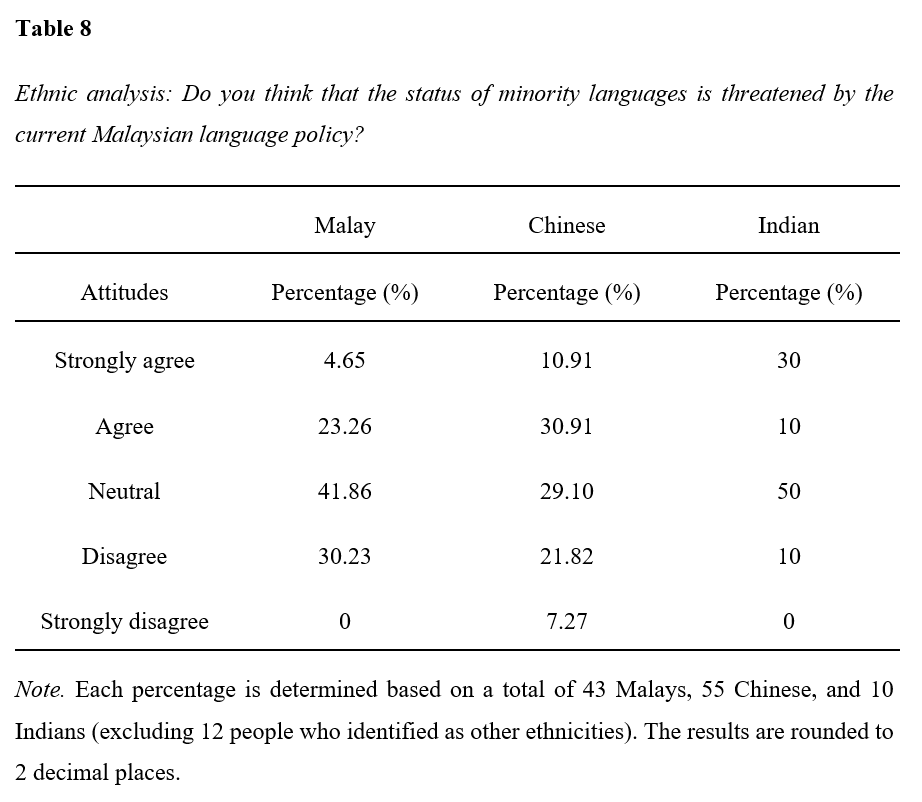

Table 7 shows the results of a questionnaire in which 120 participants were asked whether they think the current Malaysian language policy threatens the status of minority languages. According to Table 7, the most popular answer was “neutral,” which was chosen by about 34% of all participants. The second most popular answer was “agree,” chosen by about 28% of them. However, about 24% of Malaysians responded that they “disagree.” The difference in the number of people who chose “agree” and “disagree” is small and both answers were chosen by nearly the same number of people. Therefore, it can be understood that the majority of Malaysians are unable to answer either yes or no to the question of whether the status of minority languages is threatened by the current Malaysian language policy. Different results were observed, however, when the tendency of answers to this question was analyzed by ethnicity (Table 8).

Table 8 shows the results of the same questionnaire classified by ethnicity. It shows that Malays are more likely to think that the status of minority languages is not much threatened by Malaysia’s language policy, while Chinese and Indians are more likely to think that Malaysia’s language policy is threatening the status of minority languages.

While the most popular answer among Malays was “neutral,” with “disagree” as the second most chosen answer, the Chinese had a different attitude to this question. The most popular choice for them was “agree,” chosen by about 31% of all Chinese. In addition, about 11% of all Chinese responded that they “strongly agree.” Combining these two responses indicates that about 42% of all Chinese agree with this statement. This number is higher than those who either “disagree” or “strongly disagree,” which together represent about 29% of all Chinese. Compared to Malays, more Chinese tend to agree that minority languages are threatened by current language policies in Malaysia. From the Chinese perspective, the link between the status of minority languages and Malaysian language policy is obvious, and they believe that Malaysian language policy has a negative impact on their languages.

Indians also tended to answer this question differently from the other two ethnic groups. Among Indian participants, the most popular response to this question was “neutral,” chosen by 50% of them. However, the next most common response to this question was “strongly agree,” with 30% of them choosing this answer. This shows that among the three ethnic groups, Indian participants have the highest percentage of people who strongly agree that the current Malaysian language policy has a negative influence on minority languages.

While the results of this questionnaire show that the Chinese and Indians are more likely than the Malays to believe that minority languages are facing a difficult situation under the current Malaysian language policy, there is one more thing that needs to be taken into consideration. Languages such as Chinese and Tamil are in fact protected to some extent, while these languages are used by fewer people in Malaysia than the Malay language. As the results of the questionnaire above show, the number of people who think that the Malaysian language policy threatens the status of minority languages is only slightly higher than the percentage of people who think that it does not. This does not simply mean that minority languages are not being protected at all by the Malaysian government under the current language policy. A deeper understanding of this claim was gained from interviews with Malaysian citizens on this issue.

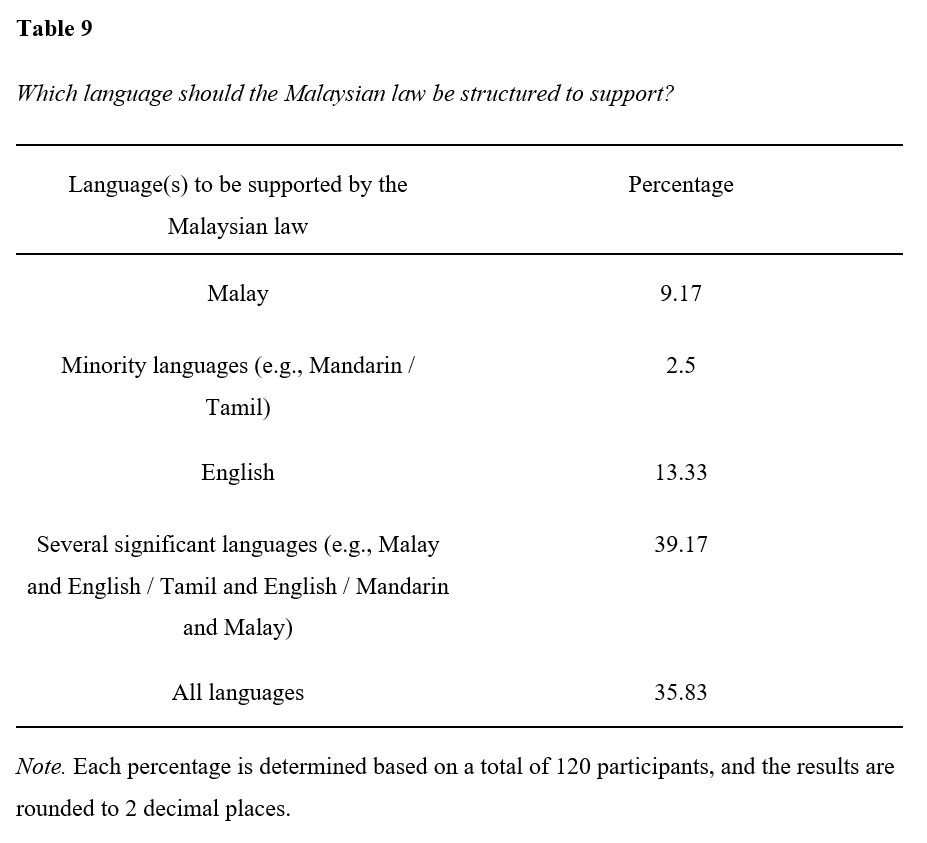

One interviewee (a boy of Chinese ethnicity) stated in his interview that he does not believe that further protection for the Chinese language should be implemented in Malaysia. He also said that he is satisfied with the current status of the Chinese language. Another interviewee (a boy of Chinese ethnicity) also told me that he does not think that the Chinese language will disappear in Malaysia because it is the language of a very strong country, the PRC. He also noted that while he does not want the government to preserve Chinese further, he also does not want the Chinese language to be suppressed in any way. The country should not say either “Go to a Chinese school” or “Do not use Chinese characters.” It is, therefore, understandable that people from minority communities oppose any further attempts to promote only their own languages, such as Mandarin and Tamil, even though, according to the results of the questionnaire, they feel that the status of minority languages in Malaysia is not sufficiently protected. Instead, many of them are seeking just enough flexibility to be able to speak their own languages freely and without suppression. This indicates that they do not intend to reform Malaysia’s current language policy, and this attitude was also observed in the results of another questionnaire (Table 9).

Table 9 shows the results of a questionnaire asking which language(s) Malaysian law should be structured to support. Table 9 shows almost all Malaysians feel that Malaysian law should support “several significant languages” or “all languages.” Nearly 39% and 36% of Malaysians chose these two answers, respectively. This finding shows that people in Malaysia believe that not only their own language but also different languages, such as English and Malay, should be equally preserved. When it comes to which language(s) should be supported by Malaysian law, the general public (not politicians, etc.) does not see a strong link between ethnic sentiments and language protection. The willingness to accept not only one’s own language but also other languages may indicate that ethnic nationalist sentiments among the Malays, Chinese, and Indians have little impact on Malaysian language policy. It then demonstrates that people of all ethnicities believe that Malaysia should be a multilingual nation rather than a single-language nation and that having multiple languages does not negatively affect their ethnic identity.

Malaysian ethnic nationalist sentiments are not only about preserving their own ethnic languages, and this implies that Chinese people do not believe that their language should be protected more than Malay or Tamil in Malaysia or that Indian nationalists are not only concerned about protecting Tamil, or that the majority of Malays do not reject the status of languages other than Malay. If ethnic consciousness seems to influence language policy, it is not because it reflects the wishes of the general Malaysian population but rather because Malaysian leaders use such ethnic sentiments as a political tool to unite the people and guide them in their desired direction.

Survival of Vernacular Schools

Malaysian language policy is not heavily influenced by ethnic nationalism, and Malaysians of all ethnicities aspire to a multilingual society in which not only their own language but also the various languages of Malaysia coexist in an appropriate manner. It is the Malaysian government, not the ethnic groups, that must take the lead in achieving such a peaceful multilingual nation because the Malaysian people are in search of more institutionalized ways to unify the country as a whole. As one of these means, some Malaysians believe that the existence of vernacular schools is an obstacle to the unity of the country and that vernacular schools using Chinese and Tamil as languages of instruction should be closed down. Some believe that ethnic languages should only be used in an unofficial capacity to promote Malaysian unity. However, the second claim about the impact of ethnic identity on Malaysian language policy is that it is important to embrace Malaysia as a multiethnic nation that includes not only Malay but also Chinese and Indian cultures in the national education scheme. Therefore, the country should never close down vernacular schools.

Based on the medium of instruction, Malaysia’s school system is divided into three categories: sekolah kebangsaan, sekolah jenis kebangsaan (Cina) (SJKC) and sekolah jenis kebangsaan (Tamil) (SJKT). While sekolah kebangsaan means Malay-medium national schools, SJKC and SJKT schools are non-Malay-medium schools that primarily use Chinese and Tamil, respectively, and these schools are called vernacular schools. Although there are some independent Chinese schools at the secondary level, all public secondary schools use Malay as the medium of instruction. These independent Chinese schools are not part of the national curriculum. It is also worth noting that there is no Tamil national-type secondary school in Malaysia (The Constitutionality of Vernacular Schools in Malaysia, 2022).

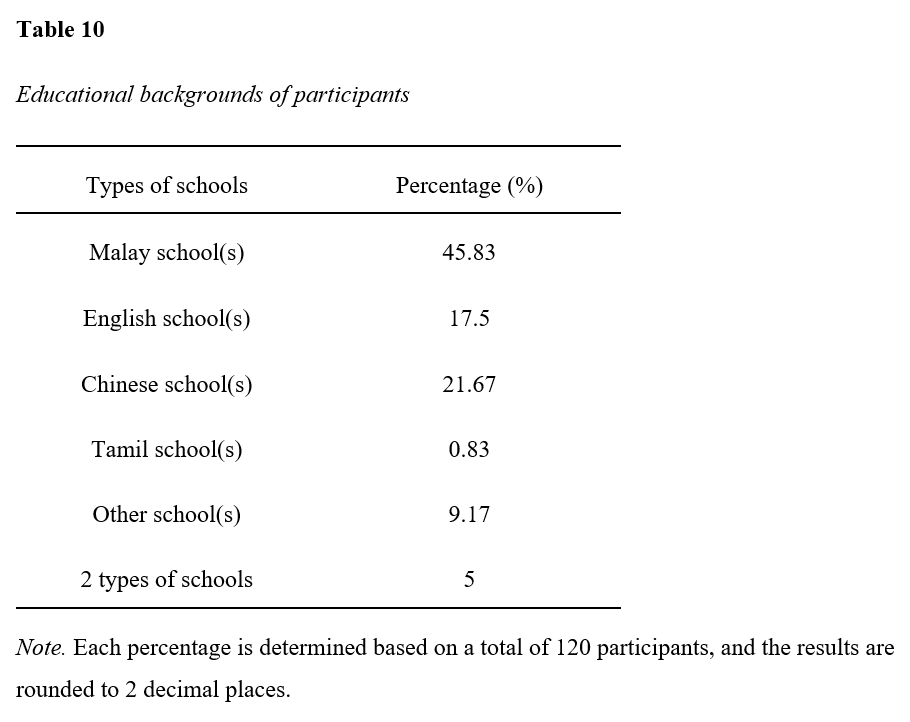

Table 10 shows the results of a questionnaire in which 120 participants were asked what type of school they attended. As can be seen in Table 10, about 46% of all participants answered that they only had attended Malay-language schools, and this was the most common answer. The second most popular answer was that they have exclusively attended Chinese-language schools, which was chosen by about 22% of all participants. This was followed by about 18% of Malaysians who answered that they had attended English medium schools, which was the third most popular answer. Only one out of the 120 respondents indicated that they had attended Tamil-medium schools, and this person was an Indian. Thus, it is clear that attending Malay-medium schools is more popular than attending vernacular schools in Malaysia.

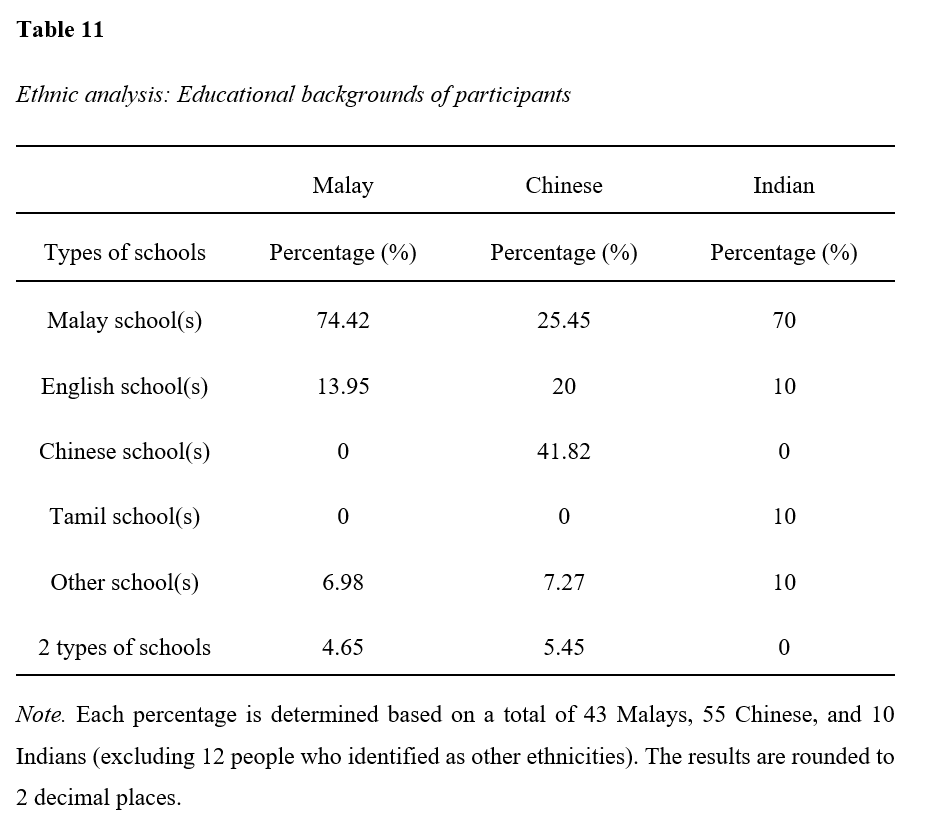

It is not only Malays who think that attending Malay-medium schools is a rational option; but Chinese and Indians also often attend Malay-medium schools. Table 11 shows the results of the same questionnaire broken down by ethnicity. According to Table 11, Malay schools are not the only schools popular among Malays. Malay schools also have a high proportion of Chinese and Indian students. It is natural for Malays to favor Malay schools over other types of schools because Malay is their ethnic language. However, it is worth noting that not only Malays but also about 25% of all Chinese and 70% of all Indians responded that they have only attended Malay language schools. This is an indication that there is support for Malay schools among the Malaysian public regardless of their ethnicity.

However, the existence of Chinese-medium schools cannot be overlooked, as the second highest percentage of respondents answered that they have attended Chinese-medium schools. Looking at the results of the questionnaire by ethnicity, the choice of “Chinese school(s)” was the most chosen answer among Chinese, while no Malays or Indians attended Chinese-only schools. About 42% of all Chinese chose this answer. It is, therefore, clear that Chinese schools remain important for Chinese students to acquire their ethnic identity and culture.

A certain number of Malaysians still attend vernacular and English schools, although Malay schools are the most common in Malaysia, regardless of ethnicity. In addition, some students who attend Malay schools transfer to English or Chinese schools in the middle of their studies, and others transfer from Chinese or Tamil schools to Malay schools. Even though the option of attending vernacular schools in Malaysia is limited to a smaller number of people, there is no reason to ignore the places for minorities. As one interviewee (a girl of Indian ethnicity) stated in her interview, vernacular schools remain important in preserving their cultures, at least for Chinese and Indians. Therefore, eliminating them would result in a serious loss of their cultures in Malaysia. Malay language schools and vernacular schools are not in competition with each other. Instead, each school serves a different purpose that can be respectfully supported and coexist.

The main research questions presented in this paper are how globalization, specifically English, affects Malaysian language policy and how ethnic identities influence the formation of Malaysian language policy. According to the research findings, the importance of English in Malaysia is increasing as a result of the rapid globalization of the world. Malaysians now see English as a necessary part of their everyday lives, as English is required for higher education and job opportunities. English is not only important for Malaysians, but it is also important for the growth of Malaysia as a nation because Malaysia will benefit from increased international exchange if more Malaysians can communicate in English. This will help the country develop.

Because Malaysians recognize the growing importance of English in the country, many of them also support the government’s continued efforts to implement the English policy. The PPSMI policy is the most notable English policy organized by the government. Despite the criticisms and challenges faced by the PPSMI policy, Malaysians generally support its implementation. As mentioned earlier, this is because Malaysians are increasingly aware of the importance of English. They hope that the government will follow stricter procedures in implementing its English policy in order to achieve better results.

Although the importance of English is growing in Malaysia, and many people consider it to be one of the most important languages, it is important to note that English will not replace the role of Malay any time soon. Some people refuse to accept the growing importance of English because they believe it threatens the status of Malay. However, research has shown that this will not happen. As interviewees said that they mix Malay and English when communicating with friends and family, English and Malay may become more mixed as globalization increases. However, the status of Malay as the national language will not be seriously affected as long as the main ethnic group in Malaysia is Malay, and Malay language education is compulsory for all students in all types of schools. Thus, rapidly increasing globalization will not threaten the current status of Malay, although it will have some impact on Malaysian language policy. English and Malay will be able to coexist peacefully.

In terms of the impact of ethnic identity on Malaysian language policy, it was found that ethnic nationalist sentiments have little influence on the direction of Malaysian language policy. Ethnic minorities agree that the current language policy threatens their own languages, but they do not expect Malaysian language policy to be designed solely to promote their own languages. In fact, they are opposed to any further efforts to promote only their own languages. Interviewees of Chinese ethnicity said that they do not believe that there is a need for additional efforts to promote the use of the Chinese language in Malaysia. People from ethnic minorities want a situation where they are not told, “Go to a Chinese school,” but they are also not told, “Do not use the Chinese language.” It can, therefore, be concluded that ethnic identities do not have a significant impact on Malaysia’s current language policy because minority communities are not seeking to reform it.

Although they do not exclusively wish to promote their own languages, the majority of Malaysians, including Malays, want Malaysia to be a more multilingual country. Mahathir Mohamad (2008) proclaimed that Malays should preserve the Malay language with an emphasis on ethnic sentiment (Malay nationalism). However, through questionnaires and interviews with Malays, it was found that many of them do not intend to use the Malay language exclusively. It is also worth noting that the same is true of Chinese and Indians. Malaysians generally want their country to be more linguistically diverse. To achieve such a multilingual environment, the efforts of the government are more important than those of ethnic groups or individuals.

Furthermore, vernacular schools should not be abolished in order for Malaysia to become a multilingual nation, though the goal is not only to protect ethnic minority languages. The closure of vernacular schools will have little impact on the preservation of Malay as the sole national language. Instead, it will be a significant loss to Malaysia’s cultural diversity, which will not lead to the establishment of harmony among different ethnic groups. It is in no one’s interest to let other ethnic communities in Malaysia implode, and getting rid of differences is not the best way to achieve racial harmony. Minority languages and Malay can coexist peacefully if Malaysia’s language policy addresses all the challenges and the government takes the lead in implementing fruitful initiatives.

Language policy has rarely been studied in the field of International Relations. Language policy is often seen as failing to examine international elements and instead focusing on domestic linguistic issues, such as people’s language behavior or the political structure that affects language use within a country. However, language policy is highly relevant to the field of International Relations, as this paper examines the connection between language policy and international elements such as globalization, colonization, and migration, demonstrating that language policy is an essential feature of the study of International Relations. Thus, as a student of International Relations, this is an area that I should approach with the knowledge and framework of International Relations, not just as a problem of a single nation.

Globalization is the increasing interconnectedness of the world through Western expansion. And as globalization increases, so does the importance of English in nations as it expands national economic competitiveness. It seems a logical choice for a developing nation to emphasize the role of English to gain national competitiveness and economic and social advantage in an increasingly globalized world. However, the government must seek the initiative to achieve both national development and the preservation of culture.

It is clear that not only language but a variety of other elements contribute to people’s sense of national and ethnic identity. However, there is no doubt that languages are still very important. People always use language(s) every day, although various other factors, such as national food and traditional clothing, can also serve as symbols of people’s national and ethnic nationalism. People cannot live a day without using language(s). Therefore, in order to create peaceful harmony among different ethnicities, each ethnic group in a nation should accommodate each other and help the government to create more diversified language policies, and there should be two-way understanding initiatives rather than just one-way direction such as only from minority communities to the majority.

Figures and Tables

References

Anderson, B. R. O. (2006). Language and Power: Exploring Political Cultures in Indonesia. Equinox Publishing.

Ang, M. C. (2009). The Chinese Education Movement in Malaysia. (Southern Papers Series. Working Papers no.2). Consejo Lationamericano de Ciencias Sociales. http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/sur-sur/20120314010205/2.ang-ming-chee.pdf

Chu, M. N., & Le, P. T. N. (2020). Language Policy Strategies of Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia. The Journal of Indian and Asian Studies, 1(02), 2050009. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2717541320500096

Drabble, J. H. (2000). An economic history of Malaysia, c. 1800-1990: The transition to modern economic growth. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230389465

Embong, A. R. (2002). Malaysia as a multicivilizational society. Macalester International, 12, 36-58. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol12/iss1/10

Gill, S. K. (2014). Language Policy Challenges in Multi-Ethnic Malaysia. Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7966-2

Guan, L. H. (2007). Ethnic Politics, National Development and Language Policy in Malaysia. In L.H. Guan & L. Suryadinata (Eds.), Language, Nation and Development in Southeast Asia (pp. 118-149). ISEAS Publishing.

Hassan, H. (2020, July 16). PPSMI Not In The Cards, But Jawi Is, Says MOE. TRP. Retrieved 16 November 2021, from https://www.therakyatpost.com/2020/07/16/ppsmi-not-in-the-cards-but-jawi-is-says-moe/

Jones, K. (2014). “A Time of Great Tension”: Memory and the Malaysian Chinese Construction of the May 13 Race Riots. Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 27(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.5070/B3272024064

Kittelstad, K. (n.d.). Examples of Globalization. YourDictionary. Retrieved 12 October 2021, from https://examples.yourdictionary.com/examples-of-globalization.html

Koh, S. Y. (2017). Race, education, and citizenship: Mobile Malaysians, British colonial legacies, and a culture of migration. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Lamba, T., & Malhotra, H. (2009). Role of Technology in Globalization with reference to Business Continuity. Global Journal of Enterprise Information System, 1(2), 70-77.

Mohamad, M. (2008). The Malay Dilemma. Marshall Cavendish Editions.

Mukherjee, D., & David, M. K. (Eds.). (2011). National Language Planning and Language Shifts in Malaysian Minority Communities: Speaking in Many Tongues. Amsterdam University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46mvhg

Mufwene, S. S. (2005). Globalization and the myth of killer languages: What’s really going on. In G. Huggan & S. Klasen (Eds.), Perspectives on endangerment, 5(21), 19-48. Georg Olms Verlag. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.553.7622&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Omar, A. H. (1985). The language policy of Malaysia: a formula for balanced pluralism. In D. Bradley (Ed.), Papers in Southeast Asian Linguistics No. 9, 39-49. Pacific Linguistics, the Australian National University. https://doi.org/10.15144/pl-a67

Rappa, A. L., & Wee, L. (2006). Language Policy and Modernity in Southeast Asia. Springer Science+ Business Media, Incorporated. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-32186-1

Robertson, R., & White, K. E. (2007). What is globalization. In G. Ritzer (Ed.), The Blackwell Companion to Globalization, 54-66. Wiley-Blackwell. http://ewclass.lecture.ub.ac.id/files/2015/02/George_Ritzer_The_Blackwell_companion_to_globaliBookFi.org_.pdf#page=72

Safran, W. (2004). Introduction: The political aspects of language. Nationalism and ethnic politics, 10(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537110490450746

Saifullah, Z. (2017). Inclusive vs. Exclusive Linguistic Nationalism: Comparing Zionist and Turkish Nationalist Language Policies. Carleton College’s Undergraduate Journal of Humanistic Studies Spring 2017, 5. https://www.carleton.edu/ujhs/past-issues/spring-2017/

Shamsul, A. B. (2004). From British to Bumiputera Rule: Local Politics and Rural Development in Peninsular Malaysia. ISEAS Publishing.

Silver, R. E. (2005). The discourse of linguistic capital: Language and economic policy planning in Singapore. Language Policy, 4(1), 47-66. https://repository.nie.edu.sg/bitstream/10497/15993/1/LP-4-1-47.pdf

Sivanandam, H., Rahim, R., & Tan, T. (2020, July 16). No plans to reintroduce English for science and maths, says Education Ministry. The Star. Retrieved 16 November 2021, from https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020/07/16/no-plans-to-reintroduce-english-for-science-and-maths-says-education-ministry

Spolsky, B. (1999). Second language learning. In J. A. Fishman (Ed.), Handbook of language and ethnic identity (pp. 181–192). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Steinhauer, H. (2004). Colonial history and language policy in insular Southeast Asia and Madagascar. In K.A. Adelaar & N. Himmelmann (Eds.), The Austronesian languages of Asia and Madagascar, 65-86. Routledge.

Sukumaran, T. (2019, May 14). Malaysia’s May 13 racial riots: 50 years on, they couldn’t happen again, could they? South China Morning Post. Retrieved 16 November 2021, from https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/society/article/3009804/malaysias-may-13-racial-riots-50-years-they-couldnt-happen-again

The Constitutionality of Vernacular Schools in Malaysia. (2022, January 21). DU Asian Law Journal. Retrieved February 27, 2022, from https://www.durhamasianlawjournal.com/post/the-constitutionality-of-vernacular-schools-in-malaysia

Tollefson, J. W. (1991). Planning Language, Planning Inequality: Language Policy in the Community (Language in Social Life Series). Addison Wesley Longman.

Yang, L. F. & Ishak, M. S. (2012). Framing controversy over language policy in Malaysia: the coverage of PPSMI reversal (teaching of mathematics and science in English) by Malaysian newspapers. Asian Journal of Communication, 22, 449 – 473. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2012.701312

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Is Ethnic Conflict Avoidable?

- Language Matters: Analysing the LGBT Rights Dialogue Between Russia and the West

- The Importance of Language in Transatlantic Relations: The INF Treaty

- The Influence of Islam on Pakistani Nationalism Towards Kashmir

- Israel-Palestine and the EU’s New ‘Language of Power’ – Plus Ça Change?

- Is Nationalism Inherently Violent?