For several years, an unwavering debate has been dominating academic and policy circles about how economic growth cannot continue indefinitely on a planet with limited resources. Capitalism, including welfare capitalism, has been long dependent on the destruction of the environment and the depletion of resources in order to operate, and “therefore, we consume what is not ‘ours’ — we consume what is owned by nature” (Johnsen et al., 2017, p. 7). Following World War II, the unquenchable desire for economic growth, greater industrial development, and accelerated consumption of Earth’s finite absorptive capacities culminated in today’s global ecological crisis. Therefore, it would not be incorrect to acknowledge that we are at the eleventh hour. Humankind is in the midst of alarming climate change (weather extremes such as wildfires, storms, floods, heatwaves, and droughts) and rampant biodiversity loss (disappearance of many common species of butterflies, bees, and other insects) that any individual can experience without resorting to complex measurement methods (Kurz, 2019). In light of this, one of the most pressing concerns is whether the idea of growth is compatible with sustainable development and whether nations can continue to align with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs) while pursuing growth policies that have overburdened resource bases and ecosystems for years.

[G]rowth and sustainable development are incompatible. Either (rich) nations give up their growth policy, or they will fail to comply with their SDGs and hence shift incalculable burdens onto their (grand-)children. In other words: Either give up income (perceived as wealth) or give up moral integrity.

(Kurz, 2019, p. 409)

As evident from Kurz’s (2019) argument, some anti-growth scholars and practitioners are deeply skeptical of the compatibility of growth and sustainable development, claiming that the two cannot coexist. In an interview, eminent ecological economist Tim Jackson states, “the conventional wisdom argues that all we have depends on this growth-based system, so why would we want to rock the boat and set ourselves on a path back to cave-dwelling?” (Great Transition Initiative, 2017). It is also interesting to note that this growth imperative is also reflected in the SDGs; for instance, SDG 8 links ‘economic growth’ with ‘decent work’ by envisioning a world of inclusive and sustainable economic growth, as well as full and productive employment and decent work for all (United Nations, 2015). The same goal envisions a world in which humanity lives in harmony with nature. However, given the current global ecological crisis and the rampant dilemma between pursuing economic growth and sustainable development, this transformational and supremely ambitious vision deserves further problematization. Given this, the essay aims to investigate the following question: How is the post-growth approach an ‘alternative’ to achieving a sustainable economy by overcoming the negative consequences of perpetual economic growth?

The goal of this paper is to unpack and critically discuss the idea that the UNSDGs advocate for a development model focused on the transition to a sustainable economy by taking into account one of the most prominent concepts within the growth debate, namely, the ‘post-growth’ approach. The essay is organized as follows. Following this brief introduction, the essay will highlight the SDGs’ framework. Thereafter, based on a critical discussion of the SDGs and the post-growth approach, the essay will argue that the SDGs are at odds with the ‘sustainable’ vision of a post-growth economy due to its self-limiting restrictions. In the final section, the essay will conclude with closing remarks, stating the need to reconceptualize the SDGs. It is necessary to perceive growth as a means to achieve environmental and social justice and not an end in itself for a transition to a true ‘sustainable’ economy.

The UNSDGs and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: A Brief Overview

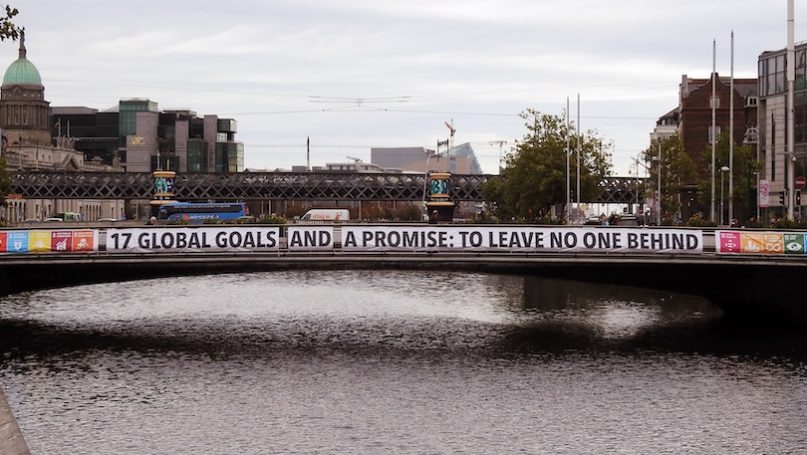

The UNSDGs were introduced in 2015 by the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, with the promise of ‘transforming our world’ through a comprehensive framework for acting toward and achieving the SDGs until 2030. The 17 SDGs and 169 targets are based on the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and aim to achieve what the MDGs did not. As the Preamble to the 2030 Agenda reads, the SDGs “are integrated and indivisible and balance the three dimensions of sustainable development: the economic, social and environmental” (United Nations, 2015). It is therefore evident that the ‘planet and environment’ have been of prime importance for the SDGs, which are “determined to protect the planet from degradation, […] through sustainable consumption and production, sustainably managing its natural resources and taking urgent action on climate change, so that it can support the needs of the present and future generations” (United Nations, 2015).

The global implementation of the SDGs has been largely spearheaded by national governments, with most of the SDGs being delivered in a top-down manner through centrally devised policies or interventions by national governments or UN agencies (Esteves et al., 2022; Jensen, 2023). This centralized and complex structure disempowers and limits non-state actors such as civil society and local communities, in turn undermining three key SDGs: SDG 16 (inclusion), SDG 17 (partnership), and SDG 5 and SDG 10 (equality). On a similar note, Easterly (2015) criticizes the ‘we’ in the UN’s 2030 Sustainability Agenda, where ‘we’ refers to world leaders, i.e., the Heads of State and Government of all UN members. Further debates on SDG implementation have reflected concerns about how parliamentary democracies are not fully democratic and, as a result, face challenges in accommodating inclusive action and debate on sustainability (Esteves et al., 2022). Critics have also pointed out that the term ‘sustainable development’ has been used as a replacement slogan for economic growth (Banerjee, 2008). In this sense, the concept of ‘sustainable growth’ may be an oxymoron (Jensen, 2023).

While rethinking the SDGs by exploring the actual/potential social and ecological contributions of community-led initiatives (CLIs), Esteves et al. (2023) highlight the SDGs’ self-limiting contradictions, especially regarding the role of economic growth. CLIs are “self-organized initiatives of people working together on an ongoing basis towards some defined sets of environmental and/or social groups, usually within defined localities or communities of place” (Esteves et al., 2022, p. 211). Although economic growth is an essential goal (SDG 8) and is considered to be the precursor for realizing the other goals, continued national and global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth seems to hinder the achievement of specific targets of reducing resource consumption, as outlined in Goals 6, 12, 13, 14, and 15. GDP calculations started during the 1930s in the backdrop of recovery from the Great Depression. Such calculations of national accounts helped in managing the war economy and post-war recovery. GDP calculates the monetary value of all services and goods produced within a country during a specific time period, usually a year or a quarter (Jensen, 2023). This finding has fostered a global call for revising and/or removing SDG8 along with “the assumed dependency, or even correlation, between achieving the SDGs and continued adherence to ongoing GDP growth as a fundamental tenet of national and international economic strategies” (Esteves et al., 2022, p. 213).

Therefore, the SDGs reflect an inherent contradiction regarding the term ‘sustainable development’ (Easterly, 2015; Esteves et al., 2022). Other critics have pointed out that the SDGs are ill-equipped to address the root causes of unsustainability and injustice (Easterly, 2015). He further argues that the SDGs are only ‘aspirational’ as each government can set its own national targets, which means a lack of clear commitments. According to Easterly (2015), the SDGs are a continuation of the UN’s venerable tradition in which “nobody is ever individually accountable for any one action, but all the leaders, UN agencies, multilateral and bilateral aid agencies, and numerous other private sector, nongovernmental, and civil society actors are collectively responsible for all the outcomes” (Easterly, 2015, p. 323).

The SDGs and Transition to a Sustainable Economy: Reflections on the Post-growth Approach

Economic growth can be defined as “an increase in the size of the economy over time. It is measured through the GDP indicator, which tracks the total value of goods and services produced” (Jensen, 2023, p. 1). Although economic growth as a material phenomenon began way back during the Industrial Revolution, the modern concept of growth was developed in the 20th century. The concept of perpetual economic growth is deeply embedded in the economic thought and institutions of contemporary capitalist society. However, this very demand and obsession with continuous economic growth have received intense criticism not only within economic theory but also within environmental natural sciences (Johnson et al., 2017). Unsurprisingly, an obsession with growth has been chastised for negatively impacting the planetary footprint of human activities and failing to address issues of inequality and wealth distribution (Evroux et al., 2023). As a result, research into a sustainable economy beyond growth that takes into account the negative effect of perpetual growth has been on the rise.

The 1972 ‘Limits to Growth’ report, developed by the Club of Rome, an international think tank, is one of the crucial contributions that highlighted how perpetual economic growth has resulted in environmental degradation (Johnsen et al., 2017; Likaj et al., 2022). Based on a new systems modeling of the relationship between resource use, population growth, economic output, and pollution, it was the first to emphasize the conflict between the natural environment and economic growth. Following that, in 1976, Fred Hirsch proposed the social limits to growth, arguing that ever-increasing welfare could not be driven by economic growth because individuals’ satisfaction from goods and services is dependent not only on their own consumption but also on the consumption of others (Likaj et al., 2022). Another social critique of economic growth was made by Richard Easterlin in 1974, which is famous as the ‘Easterlin paradox.’ It argues that after a certain point of material consumption is achieved, it no longer leads to an overall greater level of happiness or life satisfaction, i.e., well-being (Likaj et al., 2022).

The famous 1987 Brundtland Report further drew attention to aspects of climate change and environmental degradation (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987). The concept of ‘sustainable development’ was introduced by this report, which played a crucial role in reconciling economic growth with environmental sustainability and ecological balance. Furthermore, the Commission stated unequivocally how the current technological and social organization impose limits on environmental resources, in turn implying restrictions on the concept of sustainable development. However, the Commission was optimistic that such constraints could be managed and improved to pave the way for a new era of economic growth in which the global economy and global ecology must be rethought holistically. The firm belief that sustained economic growth is not only desirable but achievable through technological innovation led to the beginning of the modern ‘growth paradigm’ (Likaj et al., 2022), which was achieved in its complete form during the 1950s and 1960s (the golden age). It was the first time that the state had fully taken on the task of improving population welfare as a whole. However, during the 1970s, the growth paradigm was challenged when Western capitalism started experiencing a series of crises, such as rising unemployment, declining profit rates, increasing industrial and social unrest, and increasing inflation (Likaj et al., 2022).

A contradictory argument that is critical of over-estimating how technology can reduce environmental impacts suggests that “technology can buy time, shift an environmental problem from a “hot spot” to what seems to be less risky fields, e.g., nuclear and fossil substituted by renewable energy-presumably without any cost (the sun is sending no bills)” (Kurz, 2019, p. 410). This argument has been largely drawn from the famous ‘Jevons Paradox,’ which states that increasing resource efficiency may lead to the increase rather than the decrease of total resource consumption, as well as the concept of rebound effect (higher efficiency, lower price, higher demand). In the current growth-obsessed economic model, technology appears to be more of a crisis management tool than a causal therapy where old risks get traded against new ones, such as e-mobility-associated resource problems related to cobalt, lithium, etc. (Kurz, 2019). Other prominent studies have also postulated similar arguments that technological innovations alone cannot lead to sustainability as it can only be achieved through a continuous process of behavioral and institutional adjustment (Giampietro & Mayumi, 2018).

Clarke et al. (2014) stress that our current understanding of the nexus between nature, society, and sustainability is strictly limited to an economic metric. Therefore, the only forms of growth that are recognized within the growth debate are mostly of an economic character. This brings us to discussing the diverse concepts within the growth debate. To address the shortcomings of the current economic system, a variety of approaches have been proposed. However, most of these ambitious paradigms generate more heat than light as there is selective use of empirical data (Likaj et al., 2022). Before further discussing the post-growth approach, it is essential to briefly mention the two other prominent positions, namely, ‘inclusive green growth’ and ‘degrowth’ (decroissance). Green growth and degrowth are two opposing strategies. However, both focus on the idea of growth. While the former adopts a discourse of growth modification based on the belief that “growth occurs and has benefits, is politically hopeless to oppose and can be ameliorated today” (Likaj et al., 2022, p. 25), the latter adopts an anti-growth discourse arguing that growth is “the core problem and only economic transformation will suffice” (Likaj et al., 2022, p. 25). While the former advocates for modifying the current growth model to be more inclusive and environmentally friendly, the latter advocates abandoning growth due to planetary boundaries (Evroux et al., 2023; Jensen, 2023; Likaj et al., 2022). The third approach (post-growth), on the other hand, takes a middle ground, as will be discussed in detail further below.

For green growth, growth continues to be a central policy objective where inclusive and sustainable growth is possible through adjustments (such as decarbonization policies, environmental taxes, changes to patterns of production and composition like shifting to electric vehicles and practicing recycling, etc.) (Jensen, 2023). The green growth theory “rests on the assumption that absolute decoupling of GDP growth from resource use and carbon emissions is feasible, and at a rate sufficient to prevent dangerous climate change and other dimensions of ecological breakdown” (Hickel & Kallis, 2020, p. 469). It indulges in a top-down approach to global sustainability where the state is the major actor who mobilizes its own resources to either massively de-risk corporate investments in the markets or introduce massive interventions into these markets. Green New Deals are the most popular examples of such interventions, whereas the ‘Wall Street Consensus’ epitomizes the idea of large-scale de-risking (Hasselbalch et al., 2023). On the other hand, degrowth is a strictly anti-growth approach that argues growth to be a problem in itself and emphasizes the need for deep structural reforms, such as stopping the extraction and consumption of fossil fuels, putting limits on advertising, focusing on shared use of goods and community practices, etc. (Evroux et al., 2023).

Quite contrary to these two approaches, the post-growth approach reflects on “whether economic growth still brings the expected benefits, whether it can help solve current environmental and social problems or whether growth itself is the problem” (Jensen, 2023, p. 3). It argues that no rate of economic growth (positive, negative, or zero) is automatically correlated with environmental goods/ills and social benefit/harm. However, this should not be misinterpreted as totally abandoning growth as a policy objective. It is about finding a middle ground: neither abandoning nor relying on it. A wide range of other labels also exist around the post-growth debate, including ‘beyond growth’ and ‘a-growth’ (growth agonistic). All of them focus on escaping the unhelpful discourse of pro- and anti-growth and instead focus on issues that will actually affect social and environmental outcomes (Jensen, 2023; Likaj et al., 2022). Therefore, it is evident that various positions exist within the post-growth approach where at one end are those who are agonistic to growth to a certain extent and advocate for the replacement of mainstream economic indicators like GDP with alternative well-being metrics, and at the other end are those who advocate for a democratically controlled degrowth of the global economy which will respect ecological limits and ensure an equitable redistribution of wealth. However, the outlook that binds them all together is that “[…] the economy is embedded in a larger but physically limited ecosystem, which constrains the scale and nature of economic activity” (Hasselbalch et al., 2023, p. 4).

Proponents of this approach argue that political and economic discourse needs to focus on what is contracting, what is growing, and how consumption and production are organized instead of just talking about growth and degrowth. Its policy focuses include improving well-being, ensuring economic stability, and decisively addressing social inequalities and environmental degradation (Evroux et al., 2023; Jensen, 2023). This position is in line with a-growth, which does not take a single position on growth but rather focuses on the outcomes of any economic policies (Raworth, 2017). Therefore, the post-growth approach aims to design an economy in line with achieving substantive social and environmental goals without paying much attention to economic growth, as the “solutions offered by green/inclusive growth are seen as too incremental or acting only ex-post to remedy certain problems, while degrowth is seen as unrealistic” (Evroux et al., 2023, p. 5).

In this sense, the post-growth approach is becoming a leading concept aimed at urgently shifting policy and practice toward the directions of social equity and environmental sustainability instead of unquestioningly focusing on economic growth (GDP growth) (Likaj et al., 2022). In order to replace, adjust, or complement the GDP metric, several alternative indicators have been developed, such as the SDG index, the Social Progress Index, and the Human Development Index, to capture the multidimensional aspects of reality that are otherwise overlooked by GDP (Evroux et al., 2023; Jensen, 2023). Herman Daly’s (1972) ‘steady-state economy’ concept is the most commonly cited vision of a sustainable post-growth economy that functions within ecological boundaries. In this economy, growth is not abandoned in all sectors of the economy; instead, economic growth is deprioritized in overall policymaking.

Furthermore, Johan Rockström’s (2015) ‘Sustainability Development Paradigm for the Anthropocene’ model also indicates transforming our unsustainable economy into a steady-state economy with stable material and energy throughput to be incorporated into all levels of policymaking. For this new paradigm, the economy is not seen as an end in itself but rather a means to achieving social goals and generating prosperity within the Earth’s limits. As a matter of fact, the tenets of the post-growth economy are aligned with the famous Andean concept of ‘Buen Vivir,’ rooted in indigenous beliefs that promote a way of living based on a mutually interdependent and respectful coexistence between humans and nature (Great Transition Initiative, 2017). Another crucial idea popularized by post-growth theorists is the concept of ‘growth independence,’ which argues for making certain social benefits (such as pensions, employment, and public services) independent of growth, based on the idea that “if these objectives remain, but growth is likely to be slower or non-existent in an environmentally-constrained world, it is sensible to consider how they can be achieved in its absence” (Likaj et al., 2022, p. 27).

Following the 2008 financial crisis, Western economies have been experiencing lower growth rates compared to the past, which is also likely to continue for the foreseeable future (Likaj et al., 2022). In light of this, post-growth advocates have assumed that persuading mainstream economists and politicians who have already started becoming accustomed to the idea of low growth rather than focusing on achieving social and environmental outcomes might be easier than in the past. Therefore, the 2020 ‘Beyond Growth’ report by an advisory group to the OECD has outlined four goals that must be the paramount objectives for high-income countries instead of growth, which are rising well-being, falling inequality, environmental sustainability, and system resilience (Likaj et al., 2022; OECD, 2020). These goals must be “built into the structure of the economy from the outset, not simply hoped for as a by-product, or added after the event” (OECD, 2020, p. 16) and are enlisted as follows:

- Rising well-being: this goal focuses on improving the level of life satisfaction for individuals, along with paying attention to the accelerating sense of improving society’s condition and quality of life as a whole.

- Falling inequality: this goal is understood as reducing the gap between the wealth and incomes of the richest and poorest groups in society, reducing rates of poverty, and ensuring a relative improvement in the income, well-being, and overall opportunities of those who have been victims of systematic discrimination and disadvantage, including women, people with disability, ethnic minorities and disadvantaged geographic communities, to name a few.

- Environmental sustainability: this goal focuses on rapidly reducing greenhouse gas emissions and environmental degradation to achieve a healthy and stable level of ecosystem services and avoid catastrophic damage to the ecosystem.

- System resilience: this goal is understood as the ability of the economy to withstand environmental, financial, or other shocks without any system-wide and catastrophic effects.

Tim Jackson, one of the most prominent stalwarts in the field of post-growth economics, has debunked the widespread belief that economic growth and prosperity are inseparable (Great Transition Initiative, 2017; Jackson, 2009). He has postulated the following four pillars, which can help us envision a new post-growth economy by decoupling prosperity and growth through structural changes for redefining economic relations (Great Transition Initiative, 2017):

- Work as participation: this includes offering motivation, fulfillment, and respect to all human beings through the establishment of new work practices.

- Enterprise as service: this includes enabling mankind to flourish without destroying ecosystems through enterprise outputs. Also termed as ‘servicization’, it refers to the idea that the value of materials, such as energy, forests, chemicals, etc., is not intrinsic to the materials but rather is derived from the services they offer, for example, lighting/heating, shelter/packaging, and cleaning. Such reframing of value helps achieve dematerialization, which in turn will help reimagine fundamental assumptions about human behaviors and the economy by developing alternative forms of enterprise (Great Transition Initiative, 2017).

- Investment as commitment: this includes securing long-term prosperity for all humanity through clean or green investment, such as clean technology.

- Money as a social good: this includes an economy where money lending, creating, and borrowing systems are rooted in long-term social value creation instead of a blind focus on speculation and trading.

He has further pointed out that there are no such limits to growth because there are no limits to human creativity and ingenuity (Great Transition Initiative, 2017; Jackson, 2018). It is, therefore, imperative that despite technological progress and innovations aimed at achieving sustainability through deep cuts in resource use and emissions, the planetary emergency is fueled because of humanity’s relentless appetite for consumption.

It can, therefore, be inferred from the above discussion that the post-growth approach argues for a re-designing of the economy with a focus on achieving environmental and social goals, whether that would be accompanied by growth or not. Recent empirical studies have revealed that attempts to absolutely decouple economic growth from carbon emissions and material resource input have largely failed, as Western consumption and production patterns have been largely incompatible with IPCC climate targets and environmental limits (Koch, 2020). Therefore, to achieve the SDGs’ vision of transitioning into a sustainable economy, our growth-dependent extractive economic model needs to be substituted with a full circle, beyond-capitalism, post-growth economy to further prevent the collapse of our life-supporting environment. According to the Post-Growth Institute, an international, not-for-profit organization working to enable collective well-being within ecological limits “for a future that’s better, not bigger” (Post-Growth Institute, n.d.), several aspects of an equitable post-growth society have already been implemented such as the practice of measuring Gross National Happiness in Bhutan, the reciprocity-based Kula Exchange of the Massim archipelago, the world’s 57,000+ credit unions, etc. who are all trying to create a thriving future within ecological limits, but rarely acknowledged in the globally dominant capitalist system. Furthermore, Esteves et al. (2023) argue how some CLIs are extremely critical of economic growth and are offering prefigurative examples of post-growth societies as their operations are based on alternative economic structures, practices, and philosophies able to combine high levels of social justice, human well-being, and preservation and/or enrichment of the environment.

The ambitious SDGs indeed preach a development model that promotes a transition to a sustainable economy. However, in reality, on the one hand, it envisions humanity achieving harmony with nature and taking urgent action on climate change (Goals 6,12, 13, 14, and 15), and on the other, it calls for continued economic growth at a global level through 2030 (Goal 8), highlighting the importance of growth to be necessary for human development. Additionally, Evroux et al. (2023) point out that SDG performance is assessed on the basis of four dimensions of sustainability: fairness, environmental sustainability, macroeconomic stability, and productivity, where the last two dimensions are deeply intertwined with the idea of growth. Furthermore, according to Hickel and Kallis (2020), the concept of sustained green economic growth has been a prominent rhetoric of the SDGs as it highly relies on green growth assumptions.

Therefore, it can be argued that the SDGs are not in line with the ‘sustainable’ vision of a post-growth economy, as although they cover socio-environmental goals along with human development, it does not necessarily shift away from the pro-capitalist obsession for growth. For the ‘sustainable economy’ envisioned by the SDGs to be truly sustainable, the above-discussed internal contradictions within the SDGs need to be addressed where a true ‘sustainable’ economy would be one in which power, natural resources, and money will inherently circulate, instead of accumulating. The most significant transition from a growth to a post-growth economy would, therefore, reflect a shift from monetary growth to bio-physical parameters for steering the economy (Koch, 2020). Following Jackson’s (2009) groundbreaking argument, the transition to a sustainable economy, as espoused by the SDGs, requires dismantling the dominant culture of consumerism, as true sustainability can be achieved when real capabilities are created for people to flourish in less materialistic ways. Especially for the advanced economies of the Western world, lasting prosperity without obsessing about growth is an ecological and financial necessity. Therefore, “the demands of the new economy call on us to revisit and reframe the concepts of productivity, profitability, asset ownership, and control over the distribution of surpluses” (Jackson, 2009, p. 201). On this basis, it can be concluded that the post-growth approach is indeed an appropriate ‘alternative’ to achieve a sustainable economy by overcoming the negative consequences of perpetual economic growth. Accordingly, the SDGs need to be conceptualized to embrace this dynamic for achieving a transition to a genuine and socio-environmentally just ‘sustainable’ economy.

Conclusion

Humanity is in the middle of an apocalyptic global climate crisis coupled with an unprecedented list of threats to human security, such as intra- and inter-state conflicts, pandemics, etc. While espousing the concept of lasting prosperity without growth, Jackson (2009) exposes a major dilemma of the predominantly growth-obsessed capitalist society: on the one hand, pursuing relentless growth endangers the ecosystems on which humankind is dependent for long-term survival, and on the other, resisting growth risks sliding into social and economic collapse. What is the ‘alternative’ then? In light of this pressing dilemma, with a focus on the post-growth approach, this essay has critically discussed the various aspects of the growth debate. It has been argued that although the SDGs are the most promising vehicle for driving global sustainable development, they are not in line with the ‘sustainable’ vision of a post-growth economy.

As has been discussed earlier, a seminal contribution to rethinking the SDGs (Esteves et al., 2022) points out that for the SDGs to transcend their self-limiting internal contradictions, they need to be reconceptualized as visions in the making and not as goals or targets. This will further enable the SDGs to challenge the root causes of injustice and unsustainability instead of further reinforcing them. The SDG’s idea of transitioning into a sustainable economy must also consider the much-needed socio-ecological transition by reconsidering economic growth’s role in the pursuit of well-being and socio-environmental justice. On a similar note, to achieve a genuine transition to a sustainable economy, the SDGs require shifting away from the idea of growth obsession and promoting transitioning into a post-growth economy where the focus navigates from monetary growth to social and environmental goals. However, this definitely does not indicate propagating anti-growth but rather perceiving growth as a means to achieve the goals and not as an end in itself. Only then the 2030 Agenda’s aspirations of creating a sustainable and socially equitable world by 2030 would be fruitful.

Bibliography

Banerjee, S. B. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: The good, the bad and the ugly. Critical Sociology, 34(1), 51-79.

Clarke, J., Holt, R., & Blundel, R. (2014). Re-imagining the growth process: (Co)-evolving metaphorical representations of entrepreneurial growth. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 26(3-4), 234-256.

Daly, H. (1972). In defense of a steady-state economy. American Journal of Agricultural economy, 54(5), 945-954.

Easterly, W. (2015). The trouble with the sustainable development goals. Current History, 114(775), 322-324. https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2015.114.775.322.

Esteves, A. M., Henfrey, T., Feola, G., Penha-Lopes, G., & Sekulova, F. (2022). Rethinking the sustainable development goals: Learning with and from community-led initiatives. Sustainable Development, 31, 211-222. DOI: 10.1002/sd.2384.

Evroux, C., Spinaci, S., & Widuto, A. (2023, May). From growth to ‘beyond growth’: Concepts and challenges. European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS), 1-12. Retrieved June 02, 2023, from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2023/747107/EPRS_BRI(2023)747107_EN.pdf.

Giampietro, M., & Mayumi, K. (2018). Unraveling the complexity of the Jevons paradox: The link between innovation, efficiency, and sustainability. Conceptual Analysis, 6, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2018.00026.

Great Transition Initiative. (2017, April). Interview: How to kick the growth addiction, Tim Jackson. Retrieved May 13, 2023, from https://greattransition.org/publication/how-to-kick-the-growth-addiction?highlight=WyJwb3N0LWdyb3d0aCJd.

Hasselbalch, J. A., Kranke, M., & Chertkovskaya, E. (2023). Organizing for transformation: Post-growth in International Political Economy. Review of International Political Economy, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2023.2208871.

Hickel, J., & Kallis, G. (2020). Is green growth possible? New Political Economy, 25(4), 469-486. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1598964.

Jackson, T. (2009, March 30). Prosperity without Growth – The transition to a sustainable economy. Sustainable Development Commission. Retrieved May 10, 2023, from https://www.sd-commission.org.uk/data/files/publications/prosperity_without_growth_report.pdf.

Jackson, T. (2018, May). The Post-Growth Challenge: Secular Stagnation, Inequality and the Limits to Growth. CUSP Working Paper No 12. Guildford: University of Surrey, 1-37. Retrieved May 10, 2023, from www.cusp.ac.uk/publications.

Jensen, L. (2023, May). Beyond growth pathways towards sustainable prosperity in the EU. European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS), 1-118. Retrieved June 02, 2023, from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2023/747108/EPRS_STU(2023)747108_EN.pdf.

Johnsen, C. G., Nelund, M., Olaison, L., & Sørensen, B. M. (2017). Organizing for the post-growth economy. Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organization, 17(1), 1-21.

Koch, M. (2020). The state in the transformation to a sustainable postgrowth economy. Environmental Politics, 29(1), 115-133. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1684738.

Kurz, R. (2019). Post-growth perspectives: Sustainable development based on efficiency and on sufficiency. Public Sector Economics, 43(4), 401-422. https://doi.org/10.3326/pse.43.4.4.

Likaj, X., Jacobs, M., & Fricke, T. (2022). Growth, Degrowth or Post-growth? Towards a synthetic understanding of the growth debate. Forum for a New Economy Basic Papers. Retrieved May 14, 2023, from https://newforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/FNE-BP02-2022.pdf.

OECD. (2020, September). Beyond Growth: Towards a New Economic Approach. Retrieved May 10, 2023, from https://www.oecd.org/governance/beyond-growth-33a25ba3-en.htm.

Post Growth Institute. (n.d.). The Post Growth Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 10, 2023, from https://www.postgrowth.org/the-post-growth-encyclopedia.

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist. Cornerstone.

Rockström, J. (2015, April). Bounding the Planetary Future: Why We Need a Great Transition. Great Transition Initiative. Retrieved May 10, 2023, from https://greattransition.org/publication/bounding-the-planetary-future-why-we-need-a-great-transition.

United Nations. (2015, October 15). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for sustainable development A/Res/70/1. Retrieved May 13, 2023, from https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf.

World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Retrieved May 13, 2023, from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Assessing the Merits of Post-Fordism from a Gendered IPE Approach

- Environmental Protection or Economic Growth: What Do Nigerians Think?

- How Helpful is ‘Effective Altruism’ as an Approach to Increasing Global Justice?

- A Constructivist Approach to Chinese Interest Formation in the South China Sea

- In Search of a European Strategy? From a Normative to a Pragmatic Approach

- The (Un)intended Effects of the United Nations on the Libyan Civil War Oil Economy