Elections are high-risk moments for political violence. Over 50% of elections worldwide see more than three violent events, and roughly 30% see deadly violence (Daxecker, Amicarelli and Jung, 2019). In Kenya, since the re-introduction of multiparty politics in the 1990s, all election periods have seen elevated violence. The 1992 and 1997 elections together saw over 3,000 deaths and over 300,000 displaced (Cheeseman, 2008). The 2007 General Election was marked by particularly severe violence, with an estimated 1,500 killed, 300,000 displaced, numerous cases of sexual violence and significant damage to property (OHCHR, 2008). Subsequent election periods have been less deadly, but violence has nonetheless been prevalent. Kenyan elections are, in general, marred by violence.

The 2022 election was preceded by widespread concern about the risk of electoral violence (EV) (Kiemu, 2022). It was a tense and close run, with the victor, William Ruto, taking just 50.49% of the popular vote and the main challenger, Raila Odinga, contesting the legality of the vote in the Supreme Court, which upheld Ruto’s victory (Crisis Group, 2022). As the dust settled, the election was hailed as a “triumph for democracy” (ibid) and a “democratic turning point” (Songa and Shiferaw, 2022) with initial analysis suggesting a broadly peaceful election (ibid). Indeed, data analysis from this study shows that the 2022 election period[1] saw substantially less deadly violence than the previous three election periods. The 2022 Kenya General Election thus seems a remarkable case where widespread violence did not manifest despite tensions and a history of EV.

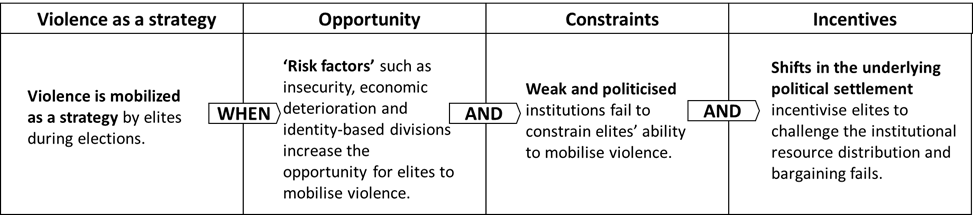

This study asks, “Why was the 2022 Kenyan General Election not marred by violence?”. It employs data analysis and interviews with key government, academia and civil society experts to investigate the patterns, dynamics, causes and mitigators of violence during the 2022 election. Given there is so far little academic analysis of 2022 EV in Kenya, this study makes an important contribution to the literature on EV in Kenya. It also makes an innovative contribution to theory. It combines two relatively separate bodies of literature, namely electoral violence theory and political settlements theory, to produce an overall framework for understanding EV. This framework unites the strengths of the electoral violence literature in understanding the risk factors, institutions, and elite-employed strategies that shape EV with the strengths of political settlements in understanding elites’ incentives for mobilising violence. It shows that this framework has efficacy in analysing the drivers of EV.

This study proceeds in five parts. First, it discusses the theoretical literature on electoral violence, delineating it into strategy, opportunity, and constraints and combining it with political settlements theory to develop an overall framework for analysing EV. This is then situated within the literature on historic EV in Kenya. Second, it outlines the methods employed for exploratory analysis of political violence data and interviews with key experts. Third, it presents and describes results using data visualisations and thematic network analysis of interviews. Fourth, it discusses the results through the lens of the theoretical framework to identify the causes of the low levels of EV in 2022. Fifth and finally, it presents conclusions and implications for understanding EV in Kenya and for EV theory overall.

This study finds that the 2022 Kenyan election was not marred by violence due to an even balance of power, strong institutions, a shift in socioeconomic risk factors, civil society intervention and elite bargaining. It shows that in Kenya, elite power relations remain constant in shaping EV and that institutional and socioeconomic dynamics have evolved significantly. More broadly it demonstrates the value of applying theory to make sense of complex, interrelated dynamics while also looking beyond theory to identify other important factors, to piece together an overall picture of the drivers and mitigators of EV.

A Framework for Electoral Violence (EV)

EV Literature: Background and Definitions

The modern study of EV can be traced to the works of Edward Mansfield and Jack Snyder, who drew on empirical studies to argue that the early stages of democratisation carry a high risk of political violence (Mansfield and Snyder, 1995, 2005; Snyder, 2000). The authors identified several causes: initially weak democratic institutions unable to mediate power, short-termist elites thrown into democratic competition and a broad base of inexperienced voters. As Snyder (2000) argues, this often results in elites leveraging state organs, especially the media, to galvanise ethno-nationalist movements and secure power, propagating divisive narratives which can lead to violent conflict.

Subsequently, there was a growth in conflict and security scholarship concerned with the relationship between elections and violent conflict. For example, Harish and Little (2017) find that whilst violence spikes around elections, democracy represses violence overall in a country. Other authors such as Brancati and Snyder (2011) and Flores and Nooruddin (2012) find that post-civil war elections are less likely to lead to violence or renewed civil war if they are delayed and if post-war structures include power sharing and a strong bureaucracy. Mansfield and Snyder’s original studies prompted a burgeoning literature on electoral violence.

As the literature has expanded, so have the various definitions of EV. Reviewing a range of definitions, Birch and Muchelinksi (2020) conclude that common across all are two characteristics. The first is temporality, that the violence must occur during the election cycle either pre-, during or post-election. Identifying a clear start and end to the election cycle can be challenging, given that election-related activities can extend far beyond the event. The authors thus suggest a defintion of 3 months before each election, the election month and 6 months following. This is to some extent arbitrary but does provide clear temporal boundaries for the study of EV. The second characteristic is causality, which meansthat the violence must have a causal link to the election process or outcome. The authors suggest that almost all forms of political violence during an election cycle can be expected to have some causal link to elections, but nevertheless, distinguishing violence clearly unrelated to the election is important. This study takes Birch and Muchelinski’s (2020) definitional characteristics to understand EV as violence which occurs during the 10-month election period and bears some causal relation to the election.

Causes of EV

A large proportion of the EV literature has been devoted to identifying the causes of EV. This review consolidates the various theories into a three-part strategy, opportunity and institutional constraints framework.

In explaining the causes of EV, most authors have maintained a focus on what Birch et al. (2020) call “electoral violence as a strategy”. In this framing, EV is one of many “tools” elites employ, usually as a last resort, to manipulate an election. It will have the intended result of political exclusion, whether in terms of candidacy, campaigning, access to information, voting freely, or from power upon victory (ibid). The authors emphasise that EV as a strategy is multi-layered and complex. Individual violence perpetrators may have personal motives that political leaders exploit, while violence may also be outsourced to violence specialists such as gangs or militias, who may, in turn, use violence as a socialisation tool (Kleinfeld, 2019). Authors have also provided modifications to this theory; for example, Collier and Vicente (2012) argue that in political equilibrium, a weak challenger is more likely to use terrorist-like violence, and a weak incumbent will use repressive violence. Ultimately, though, this theory identifies the fundamental cause of EV as the elite mobilisation of violence to manipulate elections.

While in the literature, EV as a strategy remains the most significant causal explanation, it has been complemented by a study of ‘risk factors’ which increase the opportunity for elites to mobilise EV. One of the broadest evaluations of EV risk factors is provided by Bai et al. (2015). The authors compare multiple frameworks, which in turn draw on a range of literature, to provide a framework which distinguishes between risk factors that are ‘structural’, present in the context regardless of the election moment, or ‘election-related’, specific to the election moment. The authors go on to argue that the ‘structural’ factors, such as weak democratic institutionalisation, the existence of terrorist elements and insecurity, identity-based divisions, and economic pressure, increase the opportunity for elites to mobilise violence. Indeed, research has shown that EV is more likely where elites can mobilise grievances such as socioeconomic inequality (Langer, 2006), unequal land rights (Boone, 2011) and political exclusion (Fjelde and Hoglund, 2016), and where forms of organised violence already exist which elites can manipulate (Birch et al., 2020). This shows that structural risk factors across the political, social, economic and security domains must be analysed to identify the opportunities for elites to mobilise EV.

In addition to the study of structural risk factors, other authors have placed particular emphasis on the role of institutions. Hafner-Burton et al. (2013), for example, find, based on data on election violence 1981-2004, that the pivotal considerations which determine an incumbent’s decision to deploy EV are the perceived risk of losing the election and the institutionalised constraints placed on their ability to use violence. Birch (2020) argues that weak and politicised institutions can incentivise violence, given the election victor can instrumentalise state institutions to harm the loser with economic and legal sanctions. Goldsmith (2015) argues that it takes multiple election experiences to reinforce the election itself as an institution and reduce the likelihood of EV, and thus that countries which have experienced few elections are prone to EV. While taking different angles, each of these studies demonstrates that where institutions are weak, politicised and exclusive, they fail to constrain elites’ use of violence and the risk of EV is heightened.

The ‘electoral violence’ literature seeks to explain the causes of EV through three key framings. First and foremost, EV is understood as a strategy employed by elites to manipulate an election. Second, the risk of EV is considered heightened when ‘risk factors’, including political, social, security and economic factors, increase the opportunity for violence. Finally, where institutions are politicised, weak and exclusive, they are unable to constrain or manage the use of EV.

The Incentive Gap and Political Settlements

The electoral violence literature has an incentive gap. It is recognised in this literature that EV is a strategy deployed by elites to manipulate elections, usually as a last resort. Incentives for mobilising violence are broadly considered in terms of state elites protecting their power and non-state elites as an alternative to vote-buying or contesting an electoral process (Birch, 2020). Yet there are significant risks associated with deploying violence; for states, it can erode legitimacy, while non-state actors might face state retribution (ibid). Despite this, there is little discussion of why elites choose to deploy EV within the literature. This lack of deeper analysis into incentives represents the ‘incentive gap.’

Political settlements theory can fill the incentive gap. Rather than taking a temporal moment such as elections as the subject of analysis, Political Settlements theory examines the state and power and hinges on several key concepts. First, states are understood as collections of ‘organisations’, groups of people governed by formal or informal rules of interaction (Khan, 2018). Organisations are mobilised by ‘elites’, individuals with disproportionate political and/or economic power (Cheng et al., 2018). The distribution of resources between and among organisations and elites is regulated by sets of rules and norms referred to as ‘institutions’, which can be both formal and informal (Khan, 2018; De Waal, 2009). Where elites contest institutions and resource distribution, the outcome is usually determined by their ‘holding power’ or their relative capacity to ‘hold out’ during contests, which in turn is determined by the relative strength of the organisations they control (ibid). The overall distribution of power represents the ‘political settlement’ (Cheng et al., 2018).

In the political settlements literature, the relationship between the political settlement and institutions is central to shaping incentives for violence. Cheng et al. (2018) found that when the institutionalised distribution of resources does not align with the underlying political settlement – or balance of power – elites are likely to contest, often by mobilising violence using the organisations they control. Importantly, political settlements are not static; rather, they are dynamic processes wherein elites’ relative power can shift over time, and power relations can be regularly renegotiated (ibid). Thus, as power dynamics change, so may the relative incentives to contest institutions violently. Cheng et al. (2018) argue that in moments of ‘rupture’ or political flux, elites’ agency to contest is elevated. While the authors focus on post-war moments, it is widely recognised that elections can also mark moments of rupture (Bob-Milliar and Paller, 2018; Kandeh, 1998; Charney, 1982). A political settlements approach can thus frame elections as moments of political flux when longer-term dynamics around power and resource distribution can produce the incentives for elites to deploy violence.

It is important to note that violence is not the inevitable result of elite contestation of power. Cheng et al. (2018) argue that as the balance of power shifts, elites will often strike deals, or ‘elite bargains’, to avoid violent contestation. Indeed, Blattman (2022) suggests that throughout history, elites have usually sought a peaceful bargain over violent conflict, given violence is costly. The author argues that the sum of the likely costs associated with violent conflict represents the ‘bargaining range’ and that elites will usually strike a deal provided the rewards are greater than or equal to that bargaining range. There are caveats, including when issues such as uncertainty, commitment problems and psychological biases come into play, but in general, Blattman argues, violence can be averted with a bargain. This suggests that in the case of elections where elites compete for power, they are likely to strike a bargain, but if that fails or the costs of the bargain are too high, they will be incentivised to use violence to contest or defend power.

The political settlements and electoral violence works of literature have so far remained relatively separate. In application to explaining violence, the former has tended to focus on examining violent conflict and war-to-peace transitions, while the latter has focussed on the dynamics of violence around elections. Bringing the political settlements and electoral violence pieces of literature together provides an overall theoretical framework for understanding EV. By focusing on power rather than the moment of elections, a political settlements approach allows us to position elections within broader underlying power dynamics and how they change over time. It suggests that elites may choose to use violence during elections when the balance of power shifts and when they cannot strike a bargain. The electoral violence literature then provides the framework of risk factors which increase the opportunity to mobilise violence, the institutional constraints on mobilising violence (or lack thereof) and how violence is used as a strategy during elections. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

Historic EV in Kenya

Before interrogating the 2022 election, the EV framework must be situated within historic EV in Kenya. Through the framework, we will see that elites in Kenya have deployed EV as a strategy. These elites have taken advantage of opportunities to mobilise violence and the lack of institutional constraints on its use. They have deployed EV when a shifting political settlement has provided the incentive to violently contest power, but they have also used bargaining to manage power non-violently.

In past Kenyan elections, violence has been used as a strategy by elites. During the 1990s, President Moi mobilised ethnic militia groups in the Rift Valley to displace, kill and intimidate opposition voters (Mueller, 2011; Boone, 2011). Until the 2002 election, this extra-state violence was under state control, but with an opposition victory, a coalition of political elites and gangs moved into the new opposition (Anderson, 2002; Mueller, 2008). The violence following the 2007 election was severe. A Human Rights Watch investigation suggested it was “often meticulously organised by local leaders” (HRW, 2008), and the International Criminal Court accused both opposition and state elites of mobilising violence through hierarchical networks to contest and defend power (Mueller, 2014). Similarly, in 2013, violence was concentrated in counties where local politicians exploited existing grievances to mobilise violence and secure power (HRW, 2013). The 2017 elections saw lower levels of gang violence, but there were high levels of police-perpetrated violence, and HRW (2017) found that this was disproportionately focused on opposition strongholds, suggesting a political motive. Ever since the introduction of multiparty politics in Kenya, violence has been used as a strategy during elections.

EV in Kenya has historically been enabled by security, political, economic and social risk factors, which have elevated the opportunity to mobilise violence. In terms of insecurity, as previously discussed, elites in 2007 exploited violent gangs which, since the 1990s, had evolved, proliferated, and penetrated urban areas (Mueller, 2011). Politically, the politicisation of ethnic identity has been central to historic EV in Kenya, with elites mobilising their ethnic constituencies against one another (Yieke, 2010; Cheesman et al., 2020; HRW, 1993). Violent ethnic politicisation has, in turn, been closely related to inter-ethnic socioeconomic inequalities (Cheeseman et al., 2020). In 2007, for example, EV was often perpetrated by those ethnic groups which suffered the greatest socioeconomic deprivation and exclusion from power (Stewart, 2010). Land ownership has also played a central role, with historic land grievances used to mobilise violence and land allocation used to buy violence (Boone, 2011; Klause, 2020). In Kenya, a range of factors, including the presence of violent gangs, politicised ethnicity, socioeconomic inequality, and land ownership, have historically presented elites with the opportunities to mobilise EV.

Weak and politicised institutions have historically proven unable to constrain EV in Kenya. Through the 1990s, the President weakened non-executive institutions, including the judiciary, parliament and civil service and used them as tools of patronage and repression (Mueller, 2011). The President also controlled electoral commissioner appointments (Halakhe, 2013). The result was low trust in the institutions supposed to manage electoral disputes and a weak rule of law, which in 2007 resulted in the failure to constrain EV (ibid). Kenya’s National Police Service (NPS) has also often been at the centre of EV. The NPS has suffered corruption and political manipulation, being used as a tool for repression and control by Kenya’s elites. In each election prior to 2022, police-perpetrated violence, including human rights abuses, was severe and often levied at members of political opposition groups (HRW, 2013; Osse, 2016; Claes and von Borzyskowski, 2018).

The 2010 constitution was, in part, designed to fix Kenya’s institutions. It sought to devolve power, place constraints on the executive and improve institutional independence (Kramon and Posner, 2011). The key challenge for constitutional change, however, was implementation. There was some progress in 2017 when the Kenyan Supreme Court became the second in the world to annul the election win of a sitting president (Cheeseman et al., 2020). Yet, not all institutions have shown strength. The annulment of the election was in response to apparent electoral mismanagement by the Independent Electoral Boundaries Commission (IEBC), which was charged with administering the election (ibid). Equally, despite NPS reforms, police-perpetrated violence was rife in both the 2013 and 2017 elections (Claes and von Borzyskowski, 2018). While some institutions have strengthened over Kenya’s recent history, weaknesses in key institutions such as the NPS have remained central to enabling EV in Kenya.

In 2007, Kenyan elites mobilised EV in response to a shift in the balance of power. Kenya’s politics is characterised by what Cheeseman et al. (2020) call “political tribalism”. While Kenyan politics has a strong ethnic component, no ethnic group is large enough to gain a majority vote. Elites will, therefore, build voting coalitions by exploiting assumptions that co-ethnicities will promote one another’s interests and fears that successful leaders will punish opposing groups (ibid). Following his victory in 2002, Kibaki failed to maintain his coalition, with representatives of his political allies competing with each other for seats (Cheeseman, 2008). By contrast, his 2007 challenger Odinga formed a powerful coalition, incorporating the defector Ruto and forming a ‘pentagon’ of leaders for each of the five regions (ibid). Upon the announcement of Kibaki’s re-election, Odinga and his allies were in a strong position to contest his power. The compounding factors of weak institutions unable to constrain violence and a range of risk factors that elites could manipulate meant that EV became the strategy used to contest the election.

Political settlements theory suggests that elites will usually bargain rather than deploy EV, particularly when the perceived costs of violence are high. During the 2007/8 violence, over 100,000 properties, including those of ministers, were damaged (HRW, 2008; CSIS, 2009). Ever since then, elite bargaining has characterised Kenyan politics. In 2008, mediation resulted in power-sharing between Kibaki in the role of President and Odinga in the re-established role of Prime Minister (Kayniga and Walker, 2013). In the 2010 constitution, the Prime Minister’s role was removed. Odinga subsequently lost two elections, took legal action in both cases and boycotted the 2017 re-run, naming himself the ‘people’s president’ (Cheeseman et al., 2020). 2018, then, saw another bargain. Odinga and Kenyatta appeared before national media to shake hands on a ‘new deal’ and, in 2019, launched the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI), which sought to re-establish power sharing between a President and a Prime Minister (Mbaku, 2021). The High Court eventually struck it down, but the BBI represented an attempt to manage elite contestation of power through deal-making. EV remained prolific throughout the post-2007/8 period but never reached the same levels as that election, suggesting that bargaining did indeed mitigate some EV.

The lens of the EV framework illuminates how EV has historically been deployed as a strategy by elites in Kenya; when the opportunities exist to mobilise it, institutions fail to constrain it and shift the balance of power to incentivise its use. It also shows that bargaining has been used as an alternative to violence, likely reducing levels of EV. This study applies this framework to the 2022 election to explore why it was not marred by violence, using evidence drawn from data analysis and interviews with key experts.

Methodology

This study employs a two-part methodology. First, it tests the implicit hypothesis that the 2022 Kenyan General Election was not marred by violence by examining the patterns of violence around the election period using exploratory data analysis. Second, it explores causal factors which may explain the levels of EV using interviews with key experts.

Patterns of violence and data analysis

Implicit within this study is an assumption that the 2022 Kenyan General Election was not marred by violence. This study tests this by exploring the patterns of political violence around the election period. To do this, Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) was applied to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) for Kenya. Electoral violence-specific datasets such as the DECO and the ECAV do not cover the 2022 election period. Of the up-to-date political violence datasets, ACLED provides the best granularity, coding actors, event types, fatalities and geographic location (Raleigh et al., 2010) and has been used before to analyse violence in Kenya (Kimani et al., 2021) as well as in EV studies (Daxecker, 2012; Goldsmith, 2015). For Kenya, it provides data from 1995, allowing for longitudinal analysis.

There is a limitation, however, in the form of event inflation. Since 2018, ACLED has expanded, establishing partnerships with local data suppliers and these new sources are coded into the dataset retrospectively, but only to 2018 (ACLED, n. d.). This has resulted in a large global inflation in the number of events against all event categories since 2018 (Raleigh et al., 2010). Given that 2022 was the first election year in Kenya since 2018, it is likely the dataset will capture more political violence events for that year than past election years. This will be considered when making a comparison to past elections.

As discussed, EV occurs in temporal proximity to and is causally connected to elections. ACLED does not provide events coded according to a causal relation to elections. This may be a limitation, but equally, this removes coder bias related to the selection of which events count as ‘causally connected’. To define temporal proximity, Birch and Muchelinski’s (2020, p. 218) definition of “6 months before each election, during the month of the election, and 3 months after the election” is used. Based on this data and definition, patterns of violence were analysed for the 2022 elections and compared against patterns in the previous three election periods of 2007, 2013 and 2017, as detailed in Table 1. EDA was applied to key aspects of violence patterns: how much violence occurred, when it happened and where it took place.

Investigating causes through interviews

This study goes beyond identifying patterns to investigate causes for levels of EV. This is a challenge for purely quantitative studies, as correlation does not equal causation, but qualitative methods can go some way in identifying causes (Mosely, 2013). This study employed one-to-one semi-structured interviews, which are effective for exploring complex relationships using open-ended questions and probing of answers (ibid). The guiding questions employed are detailed in Annex I.

One of the principal challenges for interview-based research is around ethics. It is incumbent upon the researcher to ensure that interviewee participation involves minimal risk and that the interviewees’ privacy, well-being and dignity are protected (Brooks, 2013). Good practice involves ensuring informed consent, the right to withdraw at any point and protecting anonymity (ibid), all of which were practised in this study. A critical consideration is around the vulnerability of interviewees. While sampling a broad population base is optimal for engaging the widest range of views possible, the vulnerability of interviewees can limit sampling. For this research, the sample was restricted, given that the focus on EV and political elite involvement could put certain interviewees, such as community members, at risk. Participants were limited to individuals already working on EV in Kenya in a professional capacity. These individuals were already publicly vocal about EV dynamics in Kenya; thus, the risks associated with their participation were minimal.

A second key challenge is around sampling. When self-selecting interviewees rather than taking a random sample of a population, the researcher is at risk of bias towards specific points of view and failing to consider others, thereby skewing the findings. A way to mitigate this is to develop an interview sampling frame based on different classes of interviewees, which helps to balance perspectives (Bleich and Pekkan, 2013). Seven interviewees from different classes of experts on Kenyan EV were selected for this study, including two officials, two civil society leaders, two academics, and one consultant. The majority of interviewees were Kenyan nationals but also included UK- and US-based experts.

Interview data was analysed with thematic analysis, based on Attride-Sterling’s (2001) Thematic Networks methodology which has been used in studies related to EV in Kenya before (Weighton and McCurdy, 2017). This enables the researcher to identify first-, second- and third-order themes across multiple interviews and explore their relationships. Theme selection will inevitably reflect some researcher bias; for example, past experiences can influence the selection of themes. Attride-Sterling asserts that interview data coding should be based on both theory and recurrent issues in interviews. This study followed this method, drawing out themes as they recurred in interviews and using theory to frame them. Direct, anonymised quotes are used throughout to better illustrate the way themes were articulated. Where issues could fall into multiple themes, they have been categorised by perceived relevance, and the subsequent discussion draws out relationships between them.

Results

Results of the Exploratory Data Analysis: Was the election marred by violence?

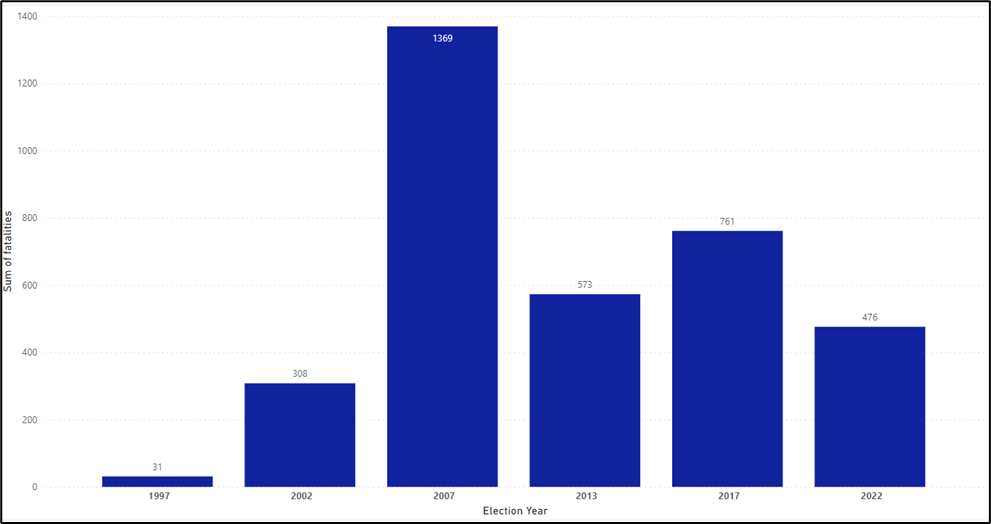

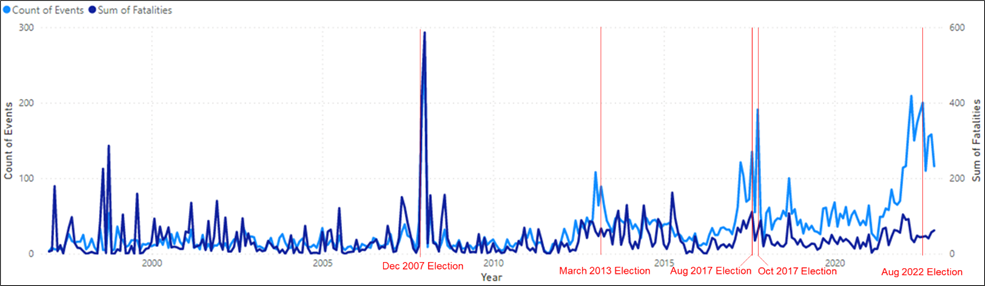

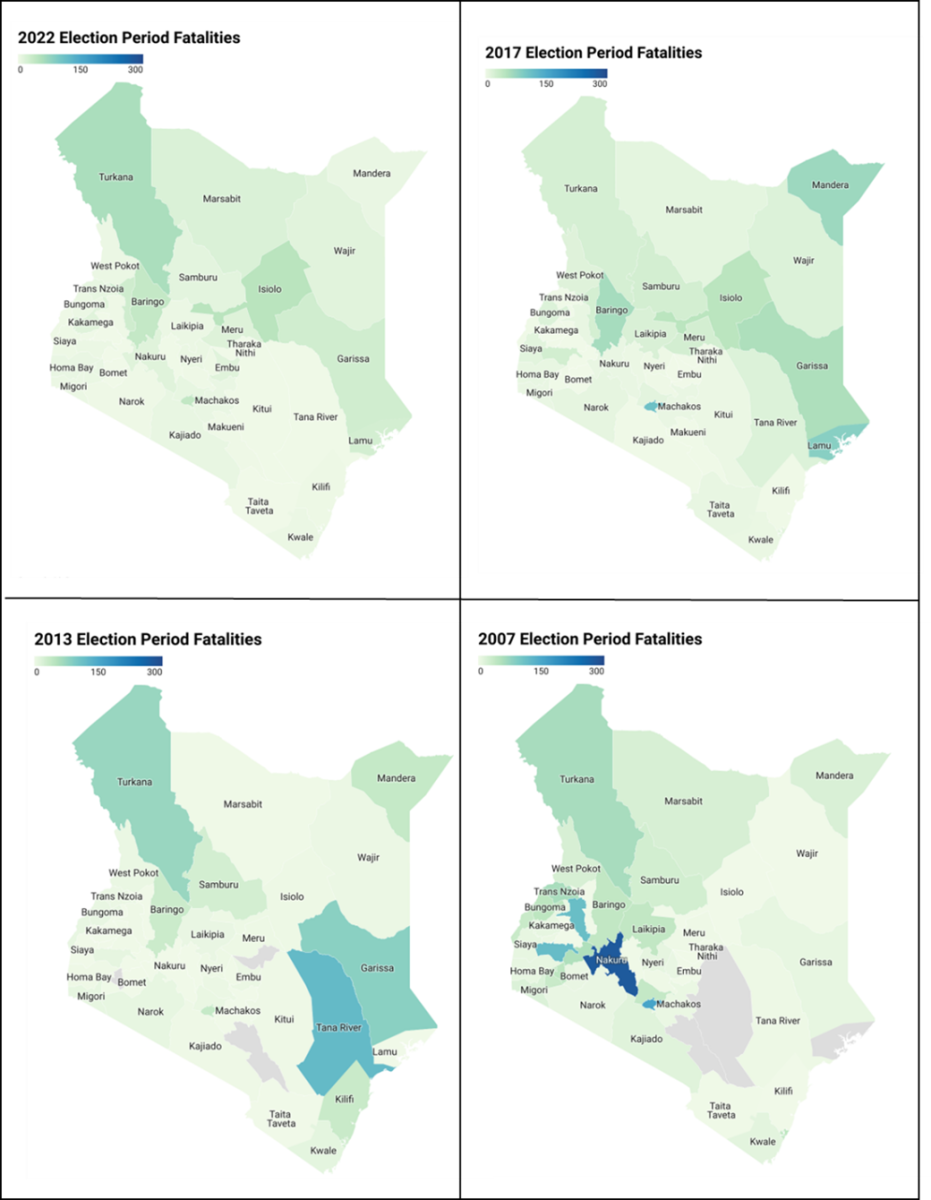

Initial EDA suggests that the 2022 election period saw significantly lower levels of EV than past election periods. As Figure 2 shows, there were fewer political violence-related fatalities in the 2022 election period than in the previous three election periods. As discussed, after 2018, ACLED recorded more events globally, and this is also true for Kenya. 2022 was the first Kenyan election since 2018, and as Figure 3 shows, ACLED records a large increase in events during the election period. Despite this, fatalities do not show a commensurate increase, which suggests that actual levels of deadly violence compared to past elections were far lower than recorded during the 2022 election. This is corroborated by the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), which collects data from a network of contacts in Kenya. RUSI records fewer events than ACLED overall but shows that compared to 2017, the 2022 election period saw a 64% reduction in election-related motivated public disorder incidents and over 75% fewer fatalities (RUSI, 2022). Overall, 2022 appears to be a remarkably violence-free election.

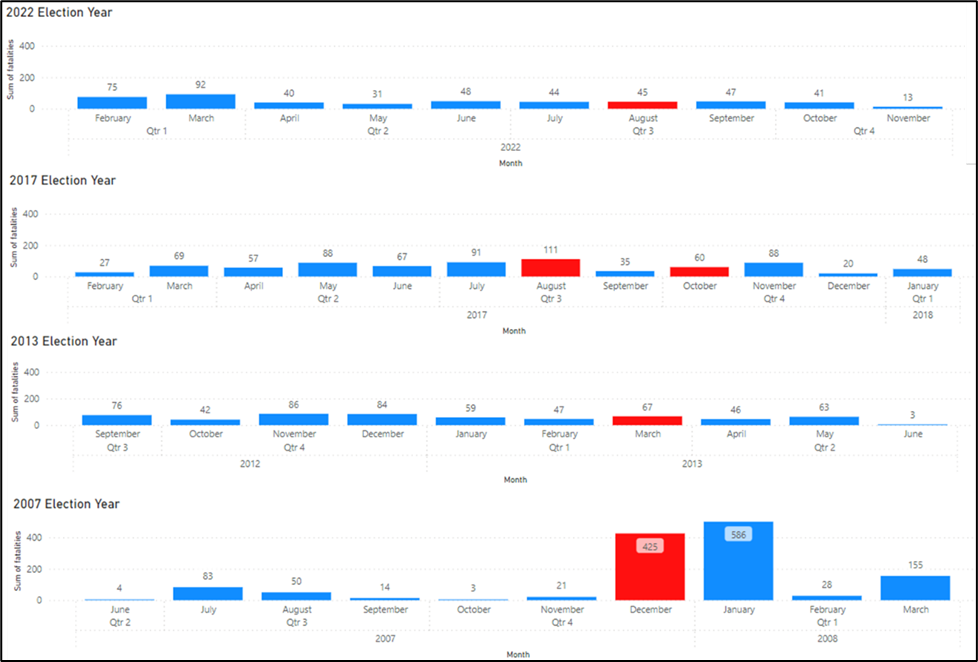

Temporal and spatial analyses further indicate comparatively low levels of EV. The intense EV of 2007 was concentrated primarily around the election month and the subsequent month and in the most contested counties (see Figures 4 and 5). Similarly, 2017 saw peak violence during the election month, and 2013 saw highly concentrated violence in Tana River, where local politicians manipulated inter-communal tensions to mobilise EV (HRW, 2013). By contrast, in 2022, the election month saw some of the lowest levels of violence of the entire election period and very little spatial concentration of violence. The deadliest months of the period were the first two, corresponding with an increase in Al Shabab activity. Hockey et al. (2023) discuss this violence specifically and suggest that there is little evidence to suggest that it was election-related and was more likely locally coordinated and related to land grievances. All counties saw lower levels of deadly violence during the 2022 period as compared to the 2017 period, except Turkana. This also seems unrelated to elections; Kariuki et al. (2022) ascribe it to illegal firearms trade across its porous borders, cattle raiding and drought-initiating water-resource conflict.

Overall, the exploratory data analysis shows that 2022 was a significantly less violent election than past elections. The election period saw much lower levels of deadly violence than the previous three election periods. The election month itself did not see escalated violence, and there was no clear spatial concentration of violence. Higher levels of deadly violence early in the election period and separately in Turkana can be explained by factors unrelated to the election.

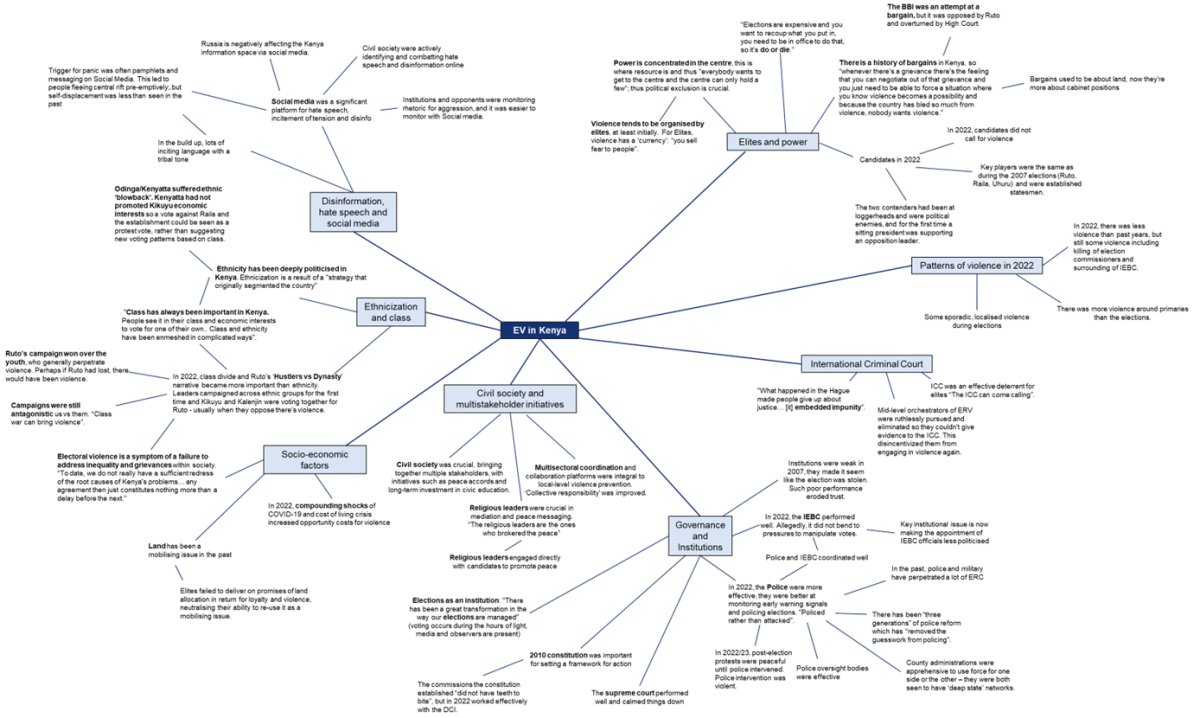

Exploring dynamics: Themes arising from interviews

This section outlines the findings from the thematic network analysis of interviews, which is illustrated in Figure 6 at the end of this section. Central to all themes was EV in Kenya. Eight second-order themes were identified: patterns of violence, elites and power, ethnicisation and class, socioeconomic factors, governance and institutions, the International Criminal Court (ICC), civil society and multistakeholder initiatives, disinformation, hate speech and social media. This section briefly details the key findings under each theme; wherever quotes are used, they were taken directly from interviewees whose identities are anonymised.

Patterns of violence

There was consensus that the 2022 election was less violent than past elections. Interviewees did report sporadic violence during and after elections, but all interviews emphasised that 2022 was significantly less violent than past elections.

Elites and power

There was a consensus that EV is generally mobilised by elites who are motivated to achieve power and wealth. One interviewee stated, “leaders in Kenya have abandoned their nationalistic vision of equity […] political power is equated to wealth”. There was also consensus that Kenyan elections are seen as winner-takes-all contests. “Everybody wants to get to the centre, and the centre can only hold a few”; “elections are expensive, and you want to recoup what you put in, you need to be in office to do that, so it’s do or die.”

Two issues related to this. First, that “violence has a currency” for elites who “sell fear to people” to affect election results. Second, there is “a history of bargains in Kenya” where violence plays a part: “whenever there’s a grievance, there’s the feeling that you [an elite] can negotiate out of that grievance, and you just need to be able to force a situation where you know violence becomes a possibility, and because the country has bled so much from violence, nobody wants violence.” It was argued that whereas bargains once focussed on land, they now focus on cabinet positions and that the recent Building Bridges Initiative was a failed attempt at such a bargain. Others spoke of 2023 post-election negotiations between Raila and Ruto as post-election bargaining.

Elite dynamics in 2022 were discussed at length. Many interviewees suggested that EV was a risk, given that Ruto, Odinga, and Kenyatta had all mobilised EV before; for the first time, a sitting president (Kenyatta) backed an opposition leader (Odinga), and Ruto and Odinga were political enemies. Equally, many observed that none of the candidates called for violence in 2022 and that Kenyatta’s unenthusiastic backing for Odinga came in relatively late, suggesting he had little motivation to use violence to secure Odinga’s win.

Ethnicisation and class

All interviewees spoke in depth about ethnicity and ethnicisation. Many stated that ethnicity has been politicised in Kenya and that this has its roots in Kenya’s turn to multiparty politics when ethnic identities were manipulated to build voting coalitions as part of a “strategy that originally segmented the country”. All agreed that this strategy had historically been at the heart of EV in Kenya.

Some felt that in 2022, there had been a dramatic shift toward class as the mobilising issue over ethnicity. Drivers were identified as a younger and more urban population less concerned with ethnicity, economic pressure and Ruto’s narrative, which framed the election as a class competition between the ‘dynasties’ of powerful and wealthy families and ‘hustlers’, the everyday Kenyans. It was noted that leaders campaigned across ethnic groups for the first time and that Kikuyu and Kalenjin were voting together for Ruto. Some argued that this reduced the risk of violence, given that when these ethnic groups are opposed, there is often violence. One interviewee argued, however, that this was misleading, given Ruto’s rhetoric was still ‘antagonistic’ and that “class war can bring chaos in this country”. Several pointed out that Ruto’s campaign won over the youth who generally perpetrate EV; as a result, many felt that a Ruto loss would have seen higher risks of EV.

There was a challenge to the class-ethnicisation dichotomy. One interviewee argued that “class has always been important in Kenya.People see it in their class and economic interests to vote for one of their own […] class and ethnicity have been enmeshed in complicated ways”. They further argued that the apparent split in Kikuyu vote may not be due to a turn to class-based politics, given “Kenyatta had done very little to promote the economic interests of the ordinary Kikuyu […] so voting for Ruto and against Kenyatta and Odinga is not necessarily totally devoid of any ethnic sentiment or logic”. This was corroborated by another interviewee, who referred to the Kikuyu’s diminishing support for Odinga as “ethnic blowback” due to his alliance with Kenyatta.

Socioeconomic factors

Several argued that socioeconomic inequality and grievance were at the root of violence in Kenya. This was discussed in terms of both horizontal and vertical socioeconomic inequalities. In relation to this, one interviewee stated: “to date, we do not really have a sufficient redress of the root causes of Kenya’s problems […] any agreement then just constitutes nothing more than a delay before the next.” Equally, however, many argued that the compounding economic shocks of COVID-19, globalisation and the hike in food prices increased the opportunity costs for people to engage in violence, thereby decreasing their motivation for violence.

Land was discussed as a key socioeconomic risk factor historically exploited by elites for violence. In relation to 2022, however, it was not raised as an EV risk factor. One interviewee suggested that this was because cabinet positions had displaced the importance of land for elites, given they could afford access to state control of wealth, which had grown with the growing economy. Another suggested that this was because President Kenyatta’s principal failure regarding promoting Kikuyu interests was around protecting and promoting their land rights in the Rift Valley, an issue which had underpinned land-related mobilisation of EV in the past, and thus that land-related inflammatory narratives had no legitimacy.

Governance and institutions

All interviewees spoke in depth about institutions. It was noted that in the past, police had perpetrated high levels of EV and that electoral institutional failure had sparked violence. Many argued that in 2022, the police, the oversight bodies of the Internal Affairs Unit (IAU) and Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA), the Independent Electoral Boundaries Commission (IEBC) and the Supreme Court were effective and well-coordinated. This was ascribed to long-term institutional strengthening, grounded in the 2010 constitution, and concerted efforts to prepare for elections. There was some criticism of the police, with arguments that post-election protests were relatively peaceful until police intervened. Overall, though, key institutions were seen to have acted effectively and independently during the 2022 election period.

The ICC

There were differing views on the role of the International Criminal Court (ICC), which had tried Kenyan leaders following previous election violence. Some felt it acted as a deterrent against elites using violence as they did not want to risk being pursued by the ICC. Others felt its failure to prosecute made people “give up about justice […] [it] embedded impunity”. One interviewee suggested that ICC investigations had indirectly disincentivised the mid-level orchestrators of past EV, given many had been pursued ruthlessly and sometimes killed by the elites accused of silencing or eliminating them. As a result, it was suggested that their appetite to engage in EV again was diminished.

Civil society and multistakeholder initiatives

Several spoke at length about the role of civil society, noting that the multistakeholder platforms used to coordinate efforts between civil society, county security and intelligence committees, religious leaders, and others were integral for enabling effective early warning and early action to prevent EV locally. Others spoke of the importance of civil society’s role in long-term civic education around exercising rights non-violently and engaging candidates in signing ‘peace accords’. Finally, the role of religious leaders in mediating conflict and engaging candidates in peace messaging was noted: “the religious leaders are the ones who brokered the peace”.

Disinformation, hate speech and social media

Many interviewees spoke about the general rhetoric around the elections and levels of disinformation and hate speech. Social media was regularly referenced as an amplifier, and some spoke of violence starting online. One interviewee noted that in the central Rift Valley, circulation of pamphlets online had prompted people to leave the area, though another interviewee said levels of such self-displacement were lower than in past elections. Others noted that significant civil society efforts were targeted at combatting online hate speech and disinformation and that institutions and parties took advantage of social media to monitor and call out candidates’ inflammatory rhetoric. Thus, social media appeared to have a dual role as an amplifier of hate speech and disinformation and a platform to counter it.

Summary

Interviews elicited a range of issues. Elite manipulation to secure power and wealth was seen as Kenya’s historic central driver of EV. This has interacted with a range of factors, including a subculture of violence, socioeconomic pressure, ethnicisation, class, disinformation and hate speech. In 2022 specifically, the election was seen as tense, with the sitting President backing an opposition candidate and Ruto mobilising an anti-establishment narrative despite being Vice President. Nevertheless, 2022 was seen as a more peaceful election overall than past elections. In explaining this, candidates’ messaging, state institutions, the ICC, civil society and religious leaders were all seen as important for preventing violence in 2022.

Explaining causes: Why the election was not marred by violence

This study asks why the 2022 Kenyan Election was not marred by violence. To uncover the causal mechanisms at work, this study interprets the results through the lens of the EV theoretical framework presented in Figure 1. It considers how far violence was used as a strategy by elites during elections and how far their decisions can be understood in terms of the incentives and opportunities to mobilise violence and the constraints on their ability to use violence. It also explores which dynamics cannot be understood through this lens and what this means for EV theory.

Violence as a strategy

The evidence from this study suggests that there was no overt use of violence as a strategy during the 2022 election, despite divisive rhetoric. Ruto campaigned around a ‘Hustlers versus Dynasties’ narrative, posing the low-income or unemployed Kenyan as struggling against the wealthy political families whose dynasties had become entrenched since Kenyan independence (Karanja, 2022). Some interviewees felt this sowed class division, but others noted that Ruto used a positive inflexion around empowerment; one interviewee, for example, recalled a voter saying, “he (Ruto) is going to empower us, and we’re going to get over all these rich families that have been dominating Kenya”. Significantly, many interviewees pointed out that the presidential candidates did not explicitly call for violence. Moreover, at the local level, many candidates engaged with civil society-led forums and signed ‘peace accords’ to promote non-violent elections. The EDA also shows that EV was much lower overall than in past elections, that it did not escalate around the election month or in contested counties, and that those escalations that did occur were unrelated to elections. Overall, despite some divisive political narratives, there was no overt use of violence as a strategy in 2022.

Opportunities to mobilise violence

In terms of risk factors affording the opportunity to mobilise violence, the results from this study suggest significant evolution in historical factors, particularly around ethnicisation, socioeconomic inequality and land. All interviewees recognised the historical importance of the politicisation of ethnicity, but many argued that in 2022, the politicisation of class gained importance. Cheeseman et al. (2020) argue that class has always been present in Kenyan politics in the perpetuation of a ‘super elite’ who strike bargains to maintain power and perpetuate their wealth. This study found, however, that in 2022, class played a different role as a key mobilising issue used particularly by Ruto; as one interviewee stated: “class began to appear more important than ethnic divisions”. It was suggested that this reflected the compounding economic shocks of COVID-19 and inflation and a growing and urbanising youth for whom ethnicity was becoming less important. Yet other interviewees suggested that ethnicity was still important and that a reduction in Kikuyu support for Odinga represented “ethnic blowback” as Kenyatta, with whom he was allied, had failed to deliver on protecting and promoting their interests (Mueller, 2022). Regardless of their relative importance, the dynamics around class and ethnicity evolved significantly in 2022.

These dynamics had implications for the risks of EV in 2022. One interviewee suggested that the fracture in Kikuyu political affiliation reduced Odinga’s ability to mobilise EV around ethnic narratives. It was also noted that the economic pressure used to frame the class-based narrative meant that most people could not afford to engage in EV. Others argued that Ruto’s ‘hustlers versus dynasties’ class-based narrative had a positive inflexion around empowerment rather than involving incitement to violence. This is supported by the EDA, which does not show violence escalations in contested counties or around key electoral moments, suggesting that neither candidate mobilised constituencies to influence the election outcome violently. Overall, the fracture of ethnic groups and economic pressure appears to have reduced the risk of EV.

It was notable that while issues of land ownership and grievances were recognised as historically significant, they did not feature in accounts of EV risks around the 2022 elections. This is perhaps explained by one interviewee’s argument that whereas once land was the most crucial aspect of political deals around elections, cabinet positions, which grant access to state control of wealth, have become more critical as the economy has grown. Equally, it may also be a result of the shift in the ethnic and class dynamics, as discussed. Klaus (2020) argues that during Kenyan elections, elites have mobilised EV through narratives that invoke fear of losing land and by acting as credible “land patrons”, protecting land rights in exchange for loyalty. Importantly, these dynamics are closely related to ethnicity, with narratives of land loss relating to capture by a different ethnic group and patron-client relationships often drawn on ethnic lines (ibid). Given the mobilising narrative of 2022 was class rather than ethnicity, it may be that land also became a less powerful mobilising narrative than past elections. Equally, given Kenyatta had failed to deliver on past promises to protect and promote Kikuyu land rights, land-based patron-client narratives may have lost credibility. Either way, it seems that land-based narratives were not a live issue that could be used to mobilise EV in 2022.

Institutions

2022 appears to be the election year where many key institutions performed well. Interviewees pointed to the lack of police-perpetrated violence. This view is supported by data from ACLED and RUSI, which show no police-inflicted deadly violence against civilians. Interviewees also suggested that the judiciary was effective. This is evidenced by the Supreme Court’s handling of Odinga’s legal challenge to the election result and, perhaps more importantly, the High Court’s decision regarding the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI). The BBI was the result of a political truce announced between Odinga and President Kenyatta in 2018, which proposed a constitutional amendment bill that would have significantly eroded Kenya’s institutions and democracy (Mbaku, 2021). In 2021, the High Court declared it unconstitutional and stated that the President had overstepped his mandate, demonstrating a high degree of judicial independence (ibid). Finally, despite some challenges around integrating new technologies (Carter Center, 2022), many interviewees believed that the IEBC acted effectively. Indeed, in contrast to 2017, it enacted a policy of electoral transparency, releasing the results from each polling station via an online portal and again, in contrast to 2017, the Supreme Court upheld the election results (Odinga vs IEBC, 2022).

These results do not suggest that more institutional strengthening is not required in Kenya. Political party primaries have suffered from personality-driven processes and poor institutionalisation, often resulting in intra-party violence (Wanyama and Elkilt, 2018). Many interviewees felt the 2022 primaries were again moments of escalating risk of violence. Equally, despite the success of the IEBC, its political independence was threatened by President Ruto’s move to have greater personal involvement in appointing IEBC commissioners following the election (Abuso, 2023). Yet overall, the 2022 election suggests that key domestic institutions were more independent and capable and that this was key for preventing EV.

Another key institution in 2022 was the ICC. In 2010, the ICC initiated an investigation into the involvement of several Kenyan political elites in the 2007 EV, including Ruto. Trials ended in 2016 with charges dropped, but evidence from this study suggests the presence of the ICC still looms in Kenyan politics. Many interviewees argued that fears of new investigations dissuaded the use of violence by political elites. Equally, those who had previously organised violence locally and could have given evidence have been ruthlessly pursued by the elites under investigation, which one interviewee argued might have disincentivised them from engaging in EV again.

This would not be the first time the ICC may have affected Kenyan elites’ behaviour during elections. Mueller (2014, p. 1) argues that the 2013 alliance between Ruto and Kenyatta, former political opponents, was “a defensive reaction to the ICC”, whereby the two used delaying tactics until they reached the highest political office when they demanded concessions. Mueller suggests that “this may have partly deterred violence in the 2013 election” (ibid, p. 2). Recent research also suggests that in Kenya, those who experience EV are more likely to support the ICC’s retributive justice against perpetrators than accept reparative justice (Aloyo, 2022). Any conclusions drawn must be treated with caution; the personal motivations of elites are almost impossible to penetrate, and several interviewees suggested the failure of the ICC to convict undermined its legitimacy. However, it is striking that despite criticism of its deterrence effect (Goldsmith and Krasner, 2003), the ICC may have been important in mitigating EV.

Elite incentives

The centrality of elite power relations to EV in Kenya has been clearly reflected in this study. Interviewees spoke about Kenyan politics being characterised by political elites, including Ruto and Odinga, focussed more on achieving power than delivering equity, employing violence as a ‘currency’ and bargaining to achieve mutual gain. The dynamics around the balance of power and related elite incentives also appeared critical for the lack of EV in 2022 in several key ways.

First, there was no clear shift in the balance of power to one side or the other. As discussed, 2022 was the first Kenyan election year where a sitting President, Kenyatta, backed an opposition candidate, Odinga. This suggests that while Ruto was Vice President, he did not have full command of the apparatus of the state. Equally, as discussed, interviewees report that Kenyatta’s backing for Odinga came in late and was not particularly enthusiastic, which suggests that Odinga also did not have the support of state organs. Certainly, data show that the police did not perpetrate violence against either political camp as has been the case in the past. Moreover, the split in the ethnic vote and the closeness of the election result itself demonstrate that neither candidate commanded a significantly powerful constituency of supporters to mobilise. This evidence shows that neither candidate shifted the balance of power significantly in their favour, suggesting little incentive for mobilising EV.

Second, it seems important that Ruto won. While existing evidence suggests that neither candidate commanded a relatively powerful constituency, several interviewees noted that Ruto was successful in courting the youth vote. His ‘hustlers vs. dynasties’ narrative played well with an urbanising youth for whom ethnicity was less important and who were suffering severe underemployment and rising costs of living. In the past, EV has often been perpetrated by young people suffering underemployment and engaged in gangs (Mueller, 2008), and many interviewees argued that had Ruto lost, youth gangs might have reacted violently. Proving this counterfactual is nigh impossible, but it certainly reflects the history of gang-related EV in Kenya and the dynamics of the 2022 election.

Finally, following the election, elite bargaining has appeared important for mitigating violence. Following a failed challenge of the election result in the Supreme Court, Odinga mobilised widespread protests. After the studied election period, in March 2023, the NPS responded violently, declaring the protests illegal and using tear gas, water cannons and live bullets against protestors (Wafula and Kazemi, 2023). In a repeat of past post-election bargaining, Ruto met with Odinga in May 2023 and agreed to review several policy demands, including the request to reverse his decision to more actively direct IEBC commissioner appointments (Crisis Group, 2023). If passed, this measure would remove a key constitutional control on Ruto’s power, and the negotiation over it effectively represents a negotiation over power. At the time of writing, the protests had subsided, and talks were reportedly ongoing (ibid). Many interviewees felt they would result in a new bargain. Elite bargaining thus seems to have been central to disincentivising elites from escalating violence.

Civil society and social media

With its focus on causes of EV and elite behaviour, the framework has missed two interrelated themes arising from interviews. The first is the role of civil society and multistakeholder violence prevention initiatives. The 2010 constitution established the Uwinao Platform for Peace, a government-led initiative that sought to foster multistakeholder responses to violence (NSCPBCM, n. d.). The platform supports peace committees, which bring together country security and intelligence committees with civil society organisations (CSOs), religious leaders, other community groups such as women and youth groups, and individual community leaders to jointly deliver violence early warning – early response systems, employing community forums and other methods to de-escalate tensions (ibid). While this initiative has been criticised for being technocratic and threatening local agencies (Githaiga, 2020), respondents in this study underlined that such committees were instrumental in preventing local-level tensions from escalating to violence. Similarly, civil society and religious leaders were credited with engaging directly with candidates to promote peaceful behaviour, for example, through signing peace accords.

The second theme is disinformation, hate speech and social media. The role of information technology is not new to Kenyan EV. Writing about the importance of SMS and the internet in the 2007 election, Cheeseman (2008, p. 169) noted that “while the main media outlets adopted a responsible tone both before and during the violence, the use of new technologies to circulate unsubstantiated allegations and falsified documents ensured that this was an election characterised by misinformation.” Misinformation featured powerfully in interviewee responses, but with a new focus on the amplifying effect of social media. Many noted the circulation of hate speech, especially against female candidates and suggested violence now started online. This reflects other contexts. In a review of Ethiopia, Iraq, Nigeria and Myanmar, Proctor (2021) found that social media can be weaponised, especially in contexts of ethnic tensions, that online narratives often spill over to populations without the internet and that these dangers are amplified during elections. The author also found that civil society presents sources of resilience to online narratives. In Kenya, interviewees noted that civil society and political opposition used social media to monitor candidates’ rhetoric and actively combat it with online pacifying messaging. This may have contributed to mitigating the risk of EV.

Conclusion and implications: Why the election was not marred by violence

This study has explored why the 2022 Kenyan General Election was not marred by violence. To do so, it has developed a framework that outlines that elites mobilise EV as a strategy when socioeconomic risk factors increase the opportunity for violence and when weak and politicised institutions fail to constrain it. It introduces political settlements theory to explain why elites will choose to mobilise EV despite the high risks associated, theorising that they are incentivised to deploy violence when the balance of power shifts in their favour and a bargain cannot be reached. This study has demonstrated the salience of this framework for understanding past drivers of EV in Kenya. EDA of ACLED data and in-depth interviews have been examined through the lens of this framework to analyse why the 2022 election was not marred by violence.

Before summarising the findings, it is important to note that the evidence from this study confirms the implicit hypothesis that the 2022 election was not marred by violence. While deadly political violence was present during the 2022 election period, levels were lower than the previous three elections and, given event inflation in the ACLED dataset, actual fatality rates are likely to have been even lower for 2022 as compared with past elections, a hypothesis which is corroborated by RUSI (2022). Moreover, violence did not escalate around key election moments and was fairly evenly distributed across the country. The marginal increase in violence during the first two months of the election period is explained by a temporary escalation in Al Shabab activity, which appears unrelated to the election. Similarly, the higher levels of violence in Turkana as compared with the 2017 election period can be explained by dynamics not directly related to elections. Overall, unlike past elections, the 2022 election was not marred by violence.

The 2022 election was not marred by violence due to an interaction between elite incentives and opportunities for violence, institutional constraints, and civil society efforts. Firstly, elite incentives for EV were limited. Pre-election, there was no clear shift in the balance of power in favour of one candidate, and while Ruto gained the support of the youth who usually perpetrate EV, he won and thus had no incentive to use EV. Post-election, elite bargaining limited the incentives for violence, likely preventing a violent escalation of opposition protests. Secondly, the opportunities to mobilise EV were limited. Ethnic- and land-based narratives, which have historically been used to mobilise EV, were negated by a fracture in Kikuyu political affiliation and the rising salience of class, while economic pressure increased the opportunity costs for engaging in violence. Thirdly, key institutions demonstrated strength in 2022. The NPS, IEBC and judiciary operated effectively and independently, constraining the ability to use violence, and the ICC may have had an additional deterrence effect for both elites and orchestrators of violence. Finally, civil society was critical for managing tensions at the local level, and social media became a new avenue to counter violent rhetoric. This analysis shows that there was no single cause for the limited levels of violence in the 2022 election. Rather, a combination of an even balance of power, strong institutions, a shift in socioeconomic risk factors, civil society intervention and elite bargaining conspired to limit EV.

This research has implications for understanding EV in Kenya and for the theory of EV more broadly. For Kenya, it demonstrates that some key dynamics have shifted. Elite power relations and bargains remain constant in shaping EV, yet in 2022, key state institutions demonstrated a greater degree of effectiveness, and class overrode ethnicity as the key mobilising issue. 2022 also demonstrated the importance of civil society’s strength and the deterrent effect of the ICC. Levels of future EV in Kenya are likely to be determined by the balance of power, the trajectory of institutional strengthening, how the issue of class plays out, whether civil society continues to actively combat EV, and Kenyan attitudes toward the ICC.

For theory on EV, this study demonstrates the value of a new framework that combines political settlements and electoral violence theories to illuminate how elite incentives are mediated through risk factors and institutions to produce strategies of violence. It further demonstrated that explanations for EV cannot be reduced to a single cause and that the linkages between different factors can be better explored through a framework. The EV framework is a powerful tool for understanding why EV occurs and are mitigated, but it must be contextualised and nuanced with context-specific factors to understand the causes and mitigators of EV fully.

While 2022 was an election year not marred by violence in Kenya, it would be foolish to assume that this is the new status quo. As Odinga and Ruto bargain, and when Kenya gears up for the 2027 election, sharp attention must be paid to the drivers and dynamics identified in this study to understand and prepare for the risk of renewed EV.

Notes

[1] Defined as the election month, the 6 months preceding and the 3 months subsequent (Birch and Muchelinski, 2020).

Figures and Tables

| Election Year | 6 Months Before Election Date | Election Date | 3 Months After Election Date |

| 2022 | February 09 2022 | August 09 2022 | November 09 2022 |

| 2017 | February 08 2017 | August 08 2017 AND October 26 2017 | January 26 2018 |

| 2013 | September 04 2012 | March 04 2013 | June 04 2013 |

| 2007 | June 27 2007 | December 27 2007 | March 2008 |

Figure 1: An overall framework for understanding EV.

Figure 2: Number of political violence-related fatalities by election period (Source: Author, Raleigh et al., 2010).

Figure 3: Number of political violence events and fatalities in Kenya 1995-2022 (Source: Author, Raleigh et al., 2010).

Figure 4: Number of political violence-related fatalities by month for each election period. Red indicates election months (Source: Author, Raleigh et al., 2010).

Figure 5: Fatalities by county for each election period (Source: Author, Raleigh et al., 2010)

Figure 6: Thematic Network Analysis of interviews (Source: Author).

Bibliography

Abuso, V. (2023, March 2). Kenya: Ruto appoints team to recruit new IEBC officials, opposition cries foul, The Africa Report [Online]. Available at: https://www.theafricareport.com/289202/kenya-ruto-appoints-team-to-recruit-new-iebc-officials-opposition-cries-foul/ (Accessed: 08/06/2023).

Almond, G. A., (1998). Political Science: The History of the Discipline, in Robert E. Goodin and Hans-Dieter Klingemann (eds.) A New Handbook of Political Science. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Aloyo, E., Dancy, G., & Dutton, Y. (2023). Retributive or reparative justice? Explaining post-conflict preferences in Kenya. Journal of Peace Research, 60(2), 258-273.

Anderson, D. M. (2002). Vigilantes, Violence and the Politics of Public Order in Kenya. African Affairs, 101(405), 531–555.

Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED). (n. d.). Adding New Sources to ACLED Coverage.[Online]. Available at: https://acleddata.com/acleddatanew/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/ACLED_Adding-New-Sources_May-2021.pdf (Accessed: 08/06/2023).

Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385-405.

Bai, J., Knarr, T., Peña, J., Willis, C., Ullah, S., & Fischer, J. (2015). Electoral Violence Prediction and Prevention: A Study of Tools for Forecasting and Best Practices. Georgetown University Democracy and Governance Studies Program Study Group for the United States Agency for International Development.

Bell, C. (2018). Political power-sharing and inclusion: Peace and transition processes. Political Settlements Research Programme: Edinburgh.

Birch, S. (2020). Electoral Violence, Corruption, and Political Order. Princeton University Press: Princeton.

Birch, S., Daxecker, U., Höglund, K. (2020). Electoral violence: An introduction. Journal of Peace Research, 57(1), 3-14.

Birch, S., Muchlinski, D. (2018). Electoral violence prevention: what works? Democratisation, 25(3), 385-403.

Birch, S., Muchlinski, D. (2020). The Dataset of Countries at Risk of Electoral Violence. Terrorism and Political Violence, (32/2), pp. 217 – 236.

Birnir, J. K., & Gohdes, A. (2018). Voting in the shadow of violence: Electoral politics and conflict in Peru. Journal of Global Security Studies, 3(2), 181-197.

Bleich, E., Pekkan, R. (2013). How to report interview data – Interviews in Contemporary Political Science, in Mosley, L. (Ed.). Interview research in political science. Cornell University Press: Ithaca.

Blattman, C. (2023). Why we fight: The roots of war and the paths to peace. Penguin.

Bob-Milliar, G. M., Paller, J. W. (2018). Democratic ruptures and electoral outcomes in Africa: Ghana’s 2016 Election. Africa Spectrum, 53(1), 5-35.

Boone, C. (2011). Politically allocated land rights and the geography of electoral violence: The case of Kenya in the 1990s. Comparative Political Studies, 44(10), 1311-1342.

Brancati, D., Snyder, J. (2013). Time to kill: The impact of election timing on post-conflict stability. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 57(5): 822–853.

Carter Center (2022). Preliminary report the Carter Center election expert mission: Presidential election, Kenya. Carter Centre, [Online]. Available at: https://www.cartercenter.org/resources/pdfs/news/peace_publications/election_reports/kenya/2022/kenya-preliminary-report-2022.pdf (Accessed: 08/06/2023).

Charney, C. R. (1982). Towards Rupture or Stasis? An Analysis of the 1981 South African General Election. African Affairs, 81(325), 527–545.

Cheng, C. Goodhand, J. Meehan, P. (2018). Synthesis paper: Securing and sustaining elite bargains that reduce violent conflict. Stabilisation Unit: London.

Cheeseman, N. (2008). The Kenyan elections of 2007: An introduction. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 2(2), 166-184.

Cheeseman, N., Kanyinga, K., Lynch, G. (2020). The political economy of Kenya: Community, clientelism, and class, in Cheeseman, N., Kanyinga, K., Lynch, G. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Kenyan Politics. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Claes, J. (2016). Electing peace: Violence prevention and impact at the polls. United States Institute of Peace Press.

Claes, J., von Borzyskowski, I. (2018). What Works in Preventing Election Violence: United States Institute of Peace.

Collier, P. (2011). Wars, guns and votes: Democracy in dangerous places. Random House: New York.

Collier, P., & Vicente, P. C. (2012). Violence, bribery, and fraud: The political economy of elections in Sub-Saharan Africa. Public choice, 153, 117-147.

Comte, A., & Martineau, H. (1855). The positive philosophy (Vol. 2). Ams Press: New York.

Crisis Group (2022). A Triumph for Kenya’s Democracy. Crisis Group [Online]. Available at: https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/kenya/triumph-kenyas-democracy (Accessed: 08/06/2023).

Crisis Group (2023). Crisis watch tracking conflict worldwide: Global overview May 2023. Crisis Watch [Online]. Available at: https://www.crisisgroup.org/crisiswatch (Accessed: 08/06/2023).

CSIS (2009). Post-election Violence in Kenya and its Aftermath. Center for Strategic and International Studies [Online.] Available at: https://www.csis.org/blogs/smart-global-health/post-election-violence-kenya-and-its-aftermath (Accessed: 09/06/2023).

Daxecker, U. E. (2012). The cost of exposing cheating: International election monitoring, fraud, and post-election violence in Africa. Journal of Peace Research, 49(4), 503-516.

Daxecker, U., Amicarelli, E., & Jung, A. (2019). Electoral contention and violence (ECAV): A new dataset. Journal of Peace Research, 56(5), 714-723.

De Waal, A. (2009). Mission without end? Peacekeeping in the African political marketplace. International Affairs, 85(1), 99-113.

Ezeibe, C. (2021). Hate Speech and Election Violence in Nigeria. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 56(4), 919–935.

Fischer, F. (1998). Beyond empiricism: policy inquiry in post positivist perspective. Policy Studies Journal, 26(1), 129-146.

Fischer, J. (2015). Electoral Violence Prediction and Prevention: A Study of Tools for Forecasting and Best Practices. Georgetown University Democracy and Governance Studies Program Study Group for the United States Agency for International Development.

Fjelde, H. (2020). Political party strength and electoral violence. Journal of Peace Research, 57(1), 140-155.

Fjelde, H., & Höglund, K. (2016). Electoral institutions and electoral violence in sub-

Saharan Africa. British Journal of Political Science, 46(2), 297-320.

Fjelde, H., & Höglund, K. (2022). Introducing the Deadly Electoral Conflict Dataset (DECO). Journal of Conflict Resolution, 66(1), 162-185.

Githaiga, N. (2020). When Institutionalisation Threatens Peacebuilding: The Case of Kenya’s Infrastructure for Peace. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 15(3), 316-330.

Goldsmith, J., & Krasner, S. D. (2003). The limits of idealism. Daedalus, 132(1), 47-63.

Goldsmith, A. A. (2015). Electoral violence in Africa revisited. Terrorism and Political Violence, 27(5), 818-837.

Hafner-Burton, E. M., Hyde, S. D., & Jablonski, R. S. (2014). When do governments resort to election violence? British Journal of Political Science, 44(1), 149-179.

Halakhe, A. B. (2013). “R2P in Practice”: Ethnic Violence, Elections and Atrocity Prevention in Kenya. Occasional paper series, 4. Global Center for the Responsibility to Protect: New York.

Hammersley, M. (2019). From positivism to post-positivism: Progress or digression? Teoria Polityki, 3, 175-188.

Harish, S. P., & Little, A. T. (2017). The political violence cycle. American Political Science Review, 111(2), 237-255.

Hartzell, C., & Hoddie, M. (2003). Institutionalising peace: Power sharing and post‐civil war conflict management. American Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 318-332.

Hockey, C., Kimaiyo, T., White, J., Zeuthen, M., Hassan, A., Lierens, E., Ellmer, A., Clark, A. (2023). Al Shabaab and the 2022 election in Kenya. RENVENT Programme.

Human Rights Watch (1993). Divide and rule: State-Sponsored Ethnic Violence in Kenya. Human Rights Watch: New York.

Human Rights Watch (2008). Ballots to bullets: Organised political violence and Kenya’s crisis of governance. Human Rights Watch, 20(1A).

Human Rights Watch (2013). High Stakes: Political Violence and the 2013 Elections in Kenya. [Online]. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2013/02/07/high-stakes/political-violence-and-2013-elections-kenya (Accessed: 12/07/2023).

Human Rights Watch, & Amnesty International (2017). “Kill Those Criminals”: Security Forces Violations in Kenya’s August 2017 Elections. Amnesty International.

Jenkins, S. (2012). Ethnicity, violence, and the immigrant-guest metaphor in Kenya. African Affairs, 111(445), 576-596.

Kandeh, J. (1998). Transition Without Rupture: Sierra Leone’s Transfer Election of 1996. African Studies Review, 41(2), 91-112. doi:10.2307/524828

Kanyinga, K., & Walker, S. (2013). Building a political settlement: The international approach to Kenya’s 2008 post-election crisis. International Journal of Security & Development, 2(2): 34, 1-21.

Karanja, J. M. (2022). ‘Hustlers versus Dynasties’: Contemporary political rhetoric in Kenya. SN Social Sciences, 2(10), 230.

Kariuki, E., Nyagah, R. G., Kosegi, D. (2022). Water-related conflicts in Turkana County: Analysis of stakeholder interests and concerns. Water, Peace and Security.

Khan, M. H. (2018). Political settlements and the analysis of institutions. African affairs, 117(469), 636-655.

Kiemu, C. (2022, July 14). Pressure points: Threat of unrest looms as Kenya’s elections approach. The Guardian [Online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/jul/04/pressure-points-threat-of-violence-builds-as-kenyas-elections-approach (Accessed: 08/06/2023).

Kimani, P., Mugo, C., & Athiany, H. (2021). Trends of Armed Conflict in Kenya from 1997 to 2021: An Exploratory Data Analysis. International Journal of Data Science and Analysis, 7(6), 161.

Klaus, K. (2020). Political Violence in Kenya: Land, Elections, and Claim-Making. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Kleinfeld, R. (2019). A savage order: How the world’s deadliest countries can forge a path to security. Vintage Books: New York.

Kramon, E., Posner, D. N. (2011). Kenya’s new constitution. Journal of Democracy, 22(2), 89-103.

Langer, A. (2005). Horizontal inequalities and violent group mobilisation in Côte d’Ivoire. Oxford Development Studies, 33(1), 25-45.

Laws, E. (2017). Donor support for post-conflict elections (GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report). Birmingham, UK: GSDRC, University of Birmingham.

Lijphart, A. (1968). Typologies of democratic systems. Comparative political studies, 1(1), 3-44.

Lijphart, A. (1977). Democracy in plural societies: A comparative exploration. Yale University Press.

López-Pintor, R. (2005). Post-conflict elections and democratisation: An experience review. USAID: Washington DC.

Mansfield, E. D., Snyder, J. (1995). Democratisation and War. Foreign Affairs, 74(3), 79–97.

Mansfield, E. D., Snyder J. (2005). Electing to Fight: Why Emerging Democracies Go to War. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

Mbaku, J. M. (2021, August 19). Is the BBI ruling a sign of judicial independence in Kenya? Brookings [Online]. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2021/08/19/is-the-bbi-ruling-a-sign-of-judicial-independence-in-kenya/ (Accessed: 08/06/2023).

Morgenthaler, S. (2009). Exploratory data analysis. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 1(1), 33-44.

Mosley, L. (2013). ‘Just Talk to People’? Interviews in Contemporary Political Science’, in Mosley, L. (Ed.). Interview research in political science. Cornell University Press: Ithaca.

Mueller, S. D. (2008). The political economy of Kenya’s crisis. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 2(2), 185-210.

Mueller, S. D. (2014). Kenya and the International Criminal Court (ICC): Politics, the election and the law. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 8(1), 25-42.

Mueller, S. D. (2011). Dying to win: Elections, political violence, and institutional decay in Kenya. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 29(1), 99-117.

Mueller, S. D. (2022, August 24). Why did Kenyans elect Ruto as President? What looks superficially like a normal election was filled with contradictions, intrigue, double-crossing and surprise shifts in ethnic loyalties, Washington Post [Online]. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/08/24/kenya-elections-kenyatta-ruto-odinga/ (Accessed: 09/06/2023).

Nation Africa (2022, September 16). ‘Shame on Judiciary’, says Raila in first speech since Supreme Court verdict. Nation Africa [Online]. Available at: https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/tanzania/news/east-africa-news/-shame-on-judiciary-says-raila-in-first-speech-since-supreme-court-verdict-3950556 (Accessed: 08/06/2023).

Nellis, G., Weaver, M., & Rosenzweig, S. C. (2016). Do parties matter for ethnic violence? Evidence from India. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 11(3), 249-277.

NSCPBCM National Steering Committee on Peace Building and Conflict Management (n. d.). National Peace Coordination. NSCPBCM [Online]. Available at: https://nscpeace.go.ke/work/national-peace-coordination (Accessed: 08/06/2023).

Odinga v. IEBC, Presidential Petition No E005 of 2022 (Kenya Sp. Ct. 2022). https://www.judiciary.go.ke/download/presidential-petition-no-e005-of-2022-consolidated-with-presidential-election-petition-nos-e001-e002-e003-e004-e007-and-e008-of-2022/

OHCHR. (2008). Report from OHCHR Fact‐finding Mission to Kenya, 6–28 February 2008. OHCHR: Geneva.

Osse, A. (2016). Police reform in Kenya: A process of ‘meddling through’. Policing and Society, 26(8), 907-924.