This article is the winner of the 2025 E-International Relations Article Award, sponsored by Edinburgh University Press, Polity, Sage, Bloomsbury, Manchester University Press, Palgrave Macmillan and Bristol University Press.

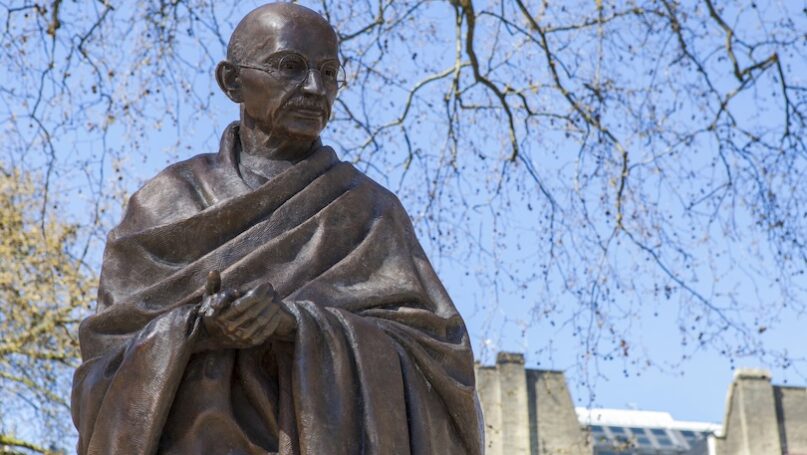

In his seminal work Spectres of Marx, Jacques Derrida introduces the concept of hauntology, a philosophy of spectrality that challenges linear notions of history and time. Against the backdrop of neoliberal triumphalism and the proclamations of a victorious end of history, Derrida argues that the “spectre of communism” is not a defeated phantom of a bygone era, but an unresolved promise of justice that continues to disrupt the present. This spectre, he posits, resides in an unresolvable aporia, neither fully present nor completely absent. It is the unfulfilled potential of an ideal, a call to a future that remains in a state of “to come.” This framework provides a powerful lens through which to re-examine the enduring legacy of Mahatma Gandhi, whose core principles of Satyagraha (the force of truth) and Ahimsa (non-violence) are often relegated to a simplistic, even naive, idealism.

In a world defined by the resurgence of militarism, geopolitical conflict, and entrenched power structures, the Gandhian vision of a peaceful, decolonized world seems a historical relic. Yet, much like the spectre of Marx, the Ghost of Gandhi persists. It is not the memory of a charismatic leader or a failed utopia; rather, it is the persistent, haunting presence of ideals that were never fully realized—an unresolved promise of justice that continues to challenge the supposed victory of hard power, authoritarianism, and the obsession with control.

For decades, many major authors and international relations theorists have treated Gandhi as a static historical figure, an idealist whose principles, while effective for a specific colonial struggle, were deemed irrelevant for the complexities of modern, state-centric geopolitics. Some foundational works on Gandhi, tend to view his ideas as a finished, historical product, tied to a specific time and place. Authors like Louis Fischer in his influential biography, The Life of Mahatma Gandhi, portrayed him as a near-perfect, saintly figure. This perspective, while reverential, can be seen as static because it presents his philosophy as a flawless, complete system. It largely overlooks his contradictions, internal struggles, and the mistakes he made, thereby removing the dynamic, experimental nature of his work. His truth and non-violence (Satyagraha and Ahimsa) become immutable ideals rather than a continuous, evolving process.

Gene Sharp’s The Politics of Nonviolent Action, reframed non-violent methods into accessible pragmatic tools for political transformation. However, it de-spiritualizes and de-philosophizes Gandhi’s approach. By focusing on non-violence as a practical technique, it distances it from its ethical core of Ahimsa—the internal, spiritual commitment to a non-violent way of being. While in the book non-violence becomes a means to an end, it marks a significant departure from Gandhi’s view of non-violence as an end in itself. Scholars in the realist international relations tradition, such as Carr and Morgenthau (1948) critique liberal, utopian, or moralist approaches. Under these frameworks, Gandhi’s non-violence is likely to be dismissed as a fringe or idealist methodology since Gandhi’s tactics would be viewed as only effective against the British Empire under specific historical conditions, thus, powerless against modern states or warfare. This view compartmentalizes Gandhi’s ideas as a “failed” or irrelevant historical footnote, and thus static in refusing to see their potential for resurgence.

The “hauntological” approach proposed in this essay as “Ghost of Gandhi” overcomes these limitations by refusing to treat Gandhi as a static object—whether he is a saint, an activist, or a politician. Instead, it views him as a “ghost,” an active and unresolved presence. Unlike the hagiographers, this approach actively confronts and integrates Gandhi’s failures—his problematic views on caste, his role in the 1947 Partition of British India—into the analysis. The “ghost” is not a perfect ideal but a painful reminder of the human cost of a flawed, even if noble, struggle. This allows for a more honest and comprehensive re-evaluation. By defining the ghost as an ‘unresolved promise of justice,’ the essay moves beyond Sharp’s earlier mentioned purely methodological approach. It argues that Ahimsa is not just a set of actions, but a continuous, spiritual struggle that requires deep introspection from all actors. The ghost haunts the present precisely because the work is unfinished and demands an ethical reckoning, not just a strategic one. This approach allows one to recontextualize Gandhi’s ideas in a way that is relevant to an ongoing modern conflict, i.e., Israel-Palestine conflict. His Satyagraha and Ahimsa are not just historical artifacts; they are spectral forces that continue to disrupt and challenge the supposedly linear progress of history, reminding us that the past is never fully ‘past’ and that these ideals can always be reborn to confront injustice. This perspective requires all actors—from nation-states to individuals—to look inward (introspect) and recognize their own complicity in perpetuating pain, thus enabling a more profound and empathetic approach to conflict resolution.

This essay will argue that the Ghost of Gandhi is an active political force, a form of haunting that operates on two distinct but interconnected levels. First, it appears as a recurring call to confront injustice with an ethical and moral clarity that transcends military and economic might. Second, it manifests as a ghostly reminder of the historical failures and complexities of Gandhi’s own life and methods, forcing a more pragmatic, less idealized, and ultimately more empathetic engagement with his legacy. Taking the case of repeated evocation of Gandhi in the Israel-Palestine conflict, the essay posits that Gandhi’s spectral presence suggests that history is not a linear progression from past to future, but a cyclical, disjointed process where the ‘dead’ ideals of truth and non-violence return to confront the perpetual injustices of the present. The Ghost of Gandhi is thus, the haunting echo of an unfulfilled potential, one that refuses to be exorcised by the relentless march of cynicism and violence.

Reevaluating the Haunting of the Present: When Dead Ideals Return

The concept of hauntology posits that the past is never truly buried; its ghosts linger and reappear, unsettling the smooth narrative of historical progress. The Ghost of Gandhi is not alone; it is part of a procession of phantoms that have returned to confront the excesses of the modern world. One of the most potent examples is the ghostly return of non-violent resistance itself. For decades, particularly in the wake of the Cold War, the prevailing geopolitical wisdom held that fundamental change could only be achieved through armed conflict, military intervention, or the overwhelming force of economic sanctions. The idea of Ahimsa as a practical political tool seemed to belong to the mid-twentieth century, a historical artifact tied to a specific struggle for independence. Yet, the twenty-first century has been defined by its non-violent movements. From the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, which mobilized millions against an authoritarian state, to the widespread climate activism that has brought global attention to an existential crisis, the tactics of peaceful civil disobedience have re-emerged with a spectral force. These movements, often decentralized and leaderless, act as a modern ‘New International,’ channeling a collective moral outrage that bypasses traditional political structures and military might. They are not merely copying Gandhi; they are an unconscious inheritance of his ghost, a recognition that justice can be pursued through moral force when conventional power is overwhelmingly stacked against them.

Another such spectre is the haunting return of sovereignty as a moral and existential concern. The post-Cold War era celebrated globalization and the dissolution of borders, painting a picture of an interconnected world where national interests would be subsumed by global capital and international institutions. This ideal of seamless integration, however, has been profoundly disrupted by the return of ethno-nationalism and the reassertion of cultural identity. What was once dismissed as a relic of the past has returned with a fierce, sometimes violent, energy. The unresolved conflicts over land, identity, and self-determination—from the Middle East to Asia to Eastern Europe—are not new wars, but the resurfacing of old ghosts, demanding that history’s unaddressed wounds be finally healed through dialogue and self-determination rather than brute force. The ghost of humanistic ideals itself has returned to haunt the cold, transactional nature of global politics.

For a time, it seemed that the discourse of human rights and universal dignity, forged in the aftermath of World War II, had become an empty platitude, a tool for powerful nations to justify intervention while turning a blind eye to their own moral failings. A renewed emphasis on empathy and shared humanity acts as a spectral force, challenging the cynicism that sees human beings as mere economic units or collateral damage. It is a haunting that reminds us of the moral debt we owe to one another, an inheritance from thinkers like Gandhi who insisted that every human life holds a sacred and inviolable worth, regardless of their geopolitical or economic status. This is particularly true in case of the Israel-Palestine conflict, that has become an example of persistent rivalry among groups, an unceasing war over contested identities and internationalization of people’s suffering for rising political stakes and selfish gains by all sides. Innumerable innocent lives have been lost in the relentless war, leaving behind local and national memories that continue to haunt the project of peaceful nation-building on both sides. It is in this context the essay will examine the dual-natured Ghost of Gandhi—as a combination of shadows (of his mistakes) that continue to haunt the Indian worldview and foreign policy towards this conflict as well as a combination of specters that still lingers for truth-seeking, justice and non-violence.

Shadows of the Ghost: Gandhi in India’s political worldview

While the Ghost of Gandhi offers a powerful promise of justice and non-violent resistance, it is a complex and contradictory spectre. One of the most profound and painful of these shadows is Gandhi’s complex and at times, deeply problematic stance on caste. While he vehemently opposed untouchability, his defense of the caste system as a form of social organization—which he termed varnashrama dharma—remains a stain on his legacy. He believed that an individual’s professional and social duties were preordained by birth, a view that was in direct conflict with Vedic varna system (Vyasa 2007) wherein varna classification is distinguished by natural qualities (guna) and the corresponding duties (karma) they are suited for, or even the radical egalitarianism of leaders like B.R. Ambedkar, who identified caste as a socio-political system of inherent inequality and oppression. This ghost of a flawed idealism haunts the present day, where caste-based discrimination and violence persist, particularly in the Indian subcontinent. The non-violent protest movements of today, such as those fighting for Dalit rights, are not only inheriting Gandhi’s methods but also correcting his historical blind spots. They are a spectral force that acknowledges the pain he caused and, in doing so, perfects the very ideals he espoused, pushing them towards a more complete and just form of non-violence. The modern Ahimsa is thus an empathetic one, born from a painful recognition that a partial truth can be as damaging as a blatant falsehood.

Another shadow is cast by the disastrous consequences of his political strategy regarding the partition of India. Despite his passionate opposition to the division of the country, his unwavering belief in the moral conscience of his political opponents and his reliance on fasting as a tool to sway them proved insufficient to prevent the mass religion-based violence that erupted before, during and after 1947. This is a ghost of political naiveté, a haunting reminder that idealism, when untempered by pragmatism and an understanding of the deep-seated political and communal divisions, can have catastrophic consequences. The Ghost of Gandhi’s politically incomplete project (and failure to achieve the same) of Hindu-Muslim unity lingers in every contemporary conflict in South Asia- the 1946 Direct Action Day, 1947 partition, 1965 India-Pakistan war, 1971 Bangladesh’s war of Independence, etc., inadvertently perpetuating cycles of violence and displacement (Chadha 2024). It forces the question: what is the cost of absolute adherence to an ideal? The answer, as witnessed in the events leading to and following the bloody 1947 partition, is a profound and lasting self-harm.

The Ghost of Gandhi has been a constant, if often contentious, presence in India’s political and geopolitical worldview, particularly in its approach to the Israel-Palestine conflict. Indian nationalists mainly guided by Gandhi in the 1920s were deeply influenced by his Khilafat Movement that aligned with Palestinian Arab Muslims and rejected Jewish homeland in Palestine. The Indian National Congress while seeking to unite Indian Muslims with the Palestinian cause opposed any partition on religious lines in India as well as in Palestine. As a result, even after India’s 1947 partition, New Delhi did not establish formal diplomatic relations with Israel, ensuring its policy towards the Jewish state be subject to its position on Palestinian cause. It was only in 1992 when a de-hyphenation was achieved in India’s relations with Palestine and Israel as India established formal diplomatic relations with the latter. Under the leadership of India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, the nation’s foreign policy was firmly rooted in a Gandhian anti-colonial stance. Nehru led India to vote against the 1947 UN Partition Plan for Palestine- a decision seen as a direct echo of Gandhi’s own views and positioned India as a champion of self-determination and a secular, non-aligned state. Nehru’s government maintained a policy of recognition of Israel but without full diplomatic relations for over four decades, driven by a deep-seated solidarity with the Palestinian cause. The foreign policy under his daughter, PM Indira Gandhi, continued this legacy and provided significant diplomatic and material support to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), viewing their struggle through the lens of a shared anti-imperialist history. She invoked Gandhi’s ideals of non-violence and resistance to oppression, extending them to international relations.

This Gandhian ghost began to shift under PM Manmohan Singh, as post-Soviet globalization and liberalization forced India’s foreign policy to be guided pragmatic economic and security interests. While Singh’s government maintained a public pro-Palestinian position, it simultaneously opened channels for close military and technological cooperation with Israel. India’s support for Palestinian state remained largely consistent even as Hamas, Palestinian militant group post-1988 Fist Intifada began posing challenge to Palestine Liberation Organization’s legitimate political representation of Palestinians, including Hamas’ 2007 takeover of the Gaza strip. Interestingly, few months after PM Singh assumed office, Gandhi’s grandson in 2004 visited West Bank city of Ramallah speaking to Palestinian refugees to ‘march home from Jordan en masse “Maybe the Israeli army would shoot and kill several. They may kill 100. They may kill 200 men, women and children. And that would shock the world” (Reuters 2007).

Under Modi since 2014, while India’s foreign policy core has continued through strategic autonomy refusal of alliance-based system with major powers, Gandhi’s legacy has once again been re-contextualized to emphasize self-reliance and civilizational national identity based on Hindutva, often shifting the focus away from his more challenging principles of absolute non-violence to issue-based retaliation. Both Israeli Jews and Palestinian Muslims are seen as victims of a war perpetrated by either side. Thus, while India has forged historically close ties with Israel, it has not abandoned its traditional support for the Palestinian cause. After his 2017 meeting with the Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas where he paid tribute at Rajghat (Gandhi’s memorial), PM Modi stated India’s carefully re-worded support for “sovereign, independent, united and viable Palestine, co-existing peacefully with Israel.” While urging Israel for a “just and durable peace in the region.” However, in his 2018 meeting, PM Modi only hoped for “an early realization of a sovereign and independent state of Palestine”.

The Ghost of Gandhi lingers in the nuanced foreign policy stance of India towards balanced ties with Israel and Palestine when Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu visited India in 2018 and called Gandhi among “humanity’s greatest prophets of inspiration” – and then weeks later Indian PM Modi became the first Indian leader to visit the occupied West Bank city of Ramallah, about a decade after Gandhi’s grandson’s 2004 visit. India’s position on the Hamas-Israel conflict is a continuity of this stance where New Delhi, much like Gandhi, stands against war and violence, has sent humanitarian assistance in Gaza but has abstained from (maintained silence on) United Nations General Assembly resolution for immediate, unconditional and permanent ceasefire by all parties. The present government’s dual approach can be seen as a residual nod to Gandhi’s original stance. This lingering principle of supporting a (two-people and) two-state solution and the rights of Palestinians, even amid flourishing relations with Israel, shows that India’s foreign policy is still haunted in part by the legacy of its founding father, i.e., outwardly balanced but inwardly shrouded in contradictions and ambiguity.

The Absent Presence: Gandhi’s Ghost in Israel-Palestine conflict

While India has eulogized and kept alive Gandhi as the nation’s father, his active presence in global politics is less obvious. Especially in theatres of violence and oppression, Gandhi’s ideals of non-violence often seem absent, a silent whisper drowned out by the roar of cannons and the rhetoric of hard power. Yet, it is precisely in this apparent absence that his spectral presence is most potently felt. The Ghost of Gandhi does not reside in the halls of power or in the speeches of military leaders; it lingers in the shadows, a constant challenge to the status quo and a defiant refusal to accept violence as a final answer.

The ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict, at first glance, appears to be a stark example of a world where Gandhi’s ghost has been utterly exorcised. It is a conflict defined by entrenched militarism, decades of land disputes, and a cycle of violence that seems intractable. The use of force, both by state and non-state actors, dominates the narrative, leaving little room for dialogue, let alone non-violent resistance. Yet, in the face of this overwhelming reality, the ghost persists. It is present in the peaceful demonstrations by Palestinian and Israeli activists advocating for a two-state solution or a shared land, in the grassroots movements that provide aid and support across dividing lines, and in the global solidarity campaigns that demand a just resolution. These acts, seemingly small against the backdrop of immense violence, are spectral forces. They are the living inheritance of Gandhi’s belief that the struggle for truth is a moral one, and that even the most formidable power structures can be challenged by a commitment to non-violence. Here, the ghost also reminds us of his political failures; his flawed counsel to Jewish people during the Holocaust now serves as a cautionary tale for those who believe that non-violence is a magic bullet, or that pure idealism can ever replace strategic pragmatism in the face of immense evil. However, a closer reading of Gandhi is necessary to uncover the permeation of his views and haunting presence in the conflict as the one who prophesized that the path to justice is fraught with the constant risk of both external and self-inflicted harm.

Gandhi’s vision for a postcolonial world order was fundamentally shaped by his conviction that Ahimsa and Satyagraha were not merely tactics for political resistance but were, in themselves, the only viable ends for a just society. He imagined a decolonized India whose geopolitical influence would emanate not from military might or economic dominance, but from moral authority and a spiritual commitment to non-violence. He believed that the nation-state, in its traditional form, was inherently flawed and that true progress lay in a decentralized, village-based governance model where conflict would be resolved through persuasion and self-suffering. This worldview directly informed his perspective on the Israel-Palestine conflict, which he viewed as a tragic consequence of British imperialism and a failure to apply the principles of justice and non-violence. He stated in an interview in 1921:

So far as I am aware, there never has been any difficulty put in the way of Jews and Christians visiting Palestine and performing all their religious rites. No canon, however, of ethics or war can possibly justify the gift by the Allies of Palestine to Jews. It would be a breach of implied faith with Indian Mussulmans in particular and the whole of India in general” (Daily Herald 1921).

In his November 1938 article in Harijan, Gandhi articulated a profound sympathy for the Jews, whom he described as “the untouchables of Christianity,” and called the Holocaust “the greatest crime of our time.” (Harijan 1938) However, he firmly opposed the idea of a Jewish state, arguing, “Palestine belongs to the Arabs in the same sense that England belongs to the English or France to the French.” (Ibid.) Viewing the British Mandate as a form of colonial aggression, he felt the “imposition” of Jews on Arabs was “wrong and inhuman”.

Thus, Gandhi’s perspective on the Jewish people’s plight was to counsel non-violent resistance, even in the face of brutal persecution, famously stating that the Jews “should have offered themselves to the butcher’s knife (Fischer 2015)” as a powerful act of Satyagraha. He believed this approach would have “aroused the world” and preserved their dignity, viewing armed resistance as a moral surrender. For the Jews in Palestine, he was equally clear, writing, “It is wrong to enter it [Palestine] under the shadow of the British gun.” He saw their reliance on British military force as a betrayal of their own spiritual heritage and a complicity in the “despoiling a people who have done no wrong to them. (Ibid.)” In Gandhi’s view, the fate of both Palestinians and Jews was inextricably linked to the need to counter the British imperial presence in both regions. His call was for both communities to abandon violence and to seek resolution through the Arab goodwill and a spiritual transformation, rather than through territorial claims or military might. His vision, therefore, was less of a two-state solution and more of a two-people solution based on mutual respect and peaceful co-existence.

The spectres of Gandhi have been invoked by leaders on all sides of the Israel-Palestine conflict, often with interpretations that serve a particular political narrative. Jewish and Israeli leadership have looked at Gandhi through a specific, often prophetic, lens to argue for most effective solution for the Palestinian cause. One view sees the armed jihad and extremism as failed strategies and calls for a Palestinian Gandhi to lead the Palestinians to non-violent resistance. This view frames non-violence not as a powerful, transformative tool but as a method of peaceful submission and a means to fill jails, thereby removing the confrontational and disruptive elements of Gandhi’s Satyagraha (Farhoud 2024). This approach, often advocated by figures outside the mainstream Israeli government, places the entire moral and political burden of the conflict on the Palestinians. They are exhorted to adopt non-violence to gain international sympathy and to prove their peaceful intentions, with the underlying assumption that their use of violence is the sole impediment to a just resolution. This narrative, while ostensibly a tribute to Gandhi, selectively ignores the fact that Gandhi’s Satyagraha was fundamentally a struggle against an occupying power, not a call for submission to it.

Interestingly, this contrasts sharply with how Palestinian, and, in some cases, influential figures have historically invoked Gandhi. For them, Gandhi is a model to be followed in some measure by the oppressed but mainly by the occupier. For instance, Dr. Mubarak Awad, referred to as the ‘Gandhi of Palestine’ actively translated works of Gandhi and Martin L. King Jr. into Arabic and founded the Palestinian Centre for the Study of Nonviolence in East Jerusalem. His teachings were instrumental in shaping the early, nonviolent tactics of the First Intifada that included boycotts of Israeli goods, civil disobedience, and mass demonstrations. The book The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine has detailed the effectiveness of the First Intifada because Israeli generals admittedly were unprepared to counter the nonviolent resistance (Khalidi 2020). Later in an interview, Dr. Awad stated that he was not Gandhi because he did not “have the concept of sacrifice as deeply as he [Gandhi] did; his willingness to sacrifice for the Indian people. I wish I would do 10% of what Gandhi did—but I’m trying to be a disciple of Gandhi, and I’m proud of that.” (Farhoud 2024) Some Palestinian figures have cited Gandhi’s words against the British to argue that Jews, as a foreign imposition, should remain in the region only through the “goodwill of the Arabs,” promoting peace and refraining from claiming land by force.

While Hamas’s founding charter does not reflect Gandhian principles, its leaders have, invoked his legacy to frame their struggle for a global audience. For example, in April 2018, Hamas political chief Ismail Haniyeh gave a political speech under a billboard with the images of Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela, declaring a new political phase for Gaza of “nonviolent resistance”. He also evoked Gandhi stating: “It is important to note Gandhi, who clearly distinguished between Zionism and Judaism in his reply to Zionist philosopher Martin Buber’s attempt to persuade him that Zionism was a just cause: ‘There is a nation in Palestine, and it must not be driven out.’” (Miller 2018) For some Palestinian leaders, Gandhi’s non-violence is crucial as a global awareness and resistance movement abroad through peaceful demonstrations, while urging Israeli Jews to adopt principles of ‘Prophetic Gandhi’ who opposed the Zionist movement and “imposition” of Jews in Arab land. This is not an abandonment of the core Hamas ideology, but a strategic invocation of Gandhi’s ghost to legitimize their cause in the eyes of the world, positioning their struggle as a peaceful effort to gain global support against what they perceive as an oppressive force. In both cases, Gandhi’s ideals are recontextualized and co-opted, sometimes ostensibly evoked and other times silently signaled, demonstrating how his legacy continues to be a living, contested, and unresolved force in modern geopolitics.

Conclusion: The Unfinished Work of the Ghost

The Ghost of Gandhi is not a museum piece to be admired; it is an active political force that demands a living, breathing engagement. It suggests that history is not a linear path that has already been paved, but a cyclical, disjointed process where the ‘dead’ ideals of truth and non-violence return to confront the perpetual injustices of the present. This ghost haunts the global stage with a dual message: a promise of what a commitment to truth and non-violence can achieve, and a warning about the fragility of idealism when untempered by pragmatism and a deep, empathetic understanding of human suffering.

The hauntological approach of this essay, allows the recontextualization of Gandhi not as a failed or successful ideology but as a continuous, ever-present struggle. By viewing his Ghost as an unresolved promise of justice, we can apply his core tenets to the nuanced, non-linear conflicts of today, in a way that overcomes the gaps of previous studies that either oversimplify or sideline him. This perspective requires all actors to undergo a profound introspection to truly approach Satyagraha and Ahimsa, recognizing that truth-seeking and non-violence are not merely external tools for protest but internal, ethical reckoning with the very nature of conflict.

Ultimately, the haunting of Gandhian ideas and the Ghost of Gandhi that is evoked when politically convenient, yet revived to justify actions that lack true Satyagraha, represents the central crisis of our moment. An honest Satyagraha, or the embrace of Ahimsa as an end in itself rather than a mere means, offers an alternate lens for the re-contextualization of Gandhi’s legacy, moving beyond a convenient misinterpretation. As Gandhi once urged for the need to “arouse the world,” a collective conscious that can only happen when the ‘Palestinian Gandhi’ and the ‘Prophetic Gandhi’ listen to each other and are set free into a living, active non-violent action toward Ahimsa. Only when Gandhi’s ghost, through these spectres, is liberated from its static symbol can it become a dynamic, ethical force for truth and justice in the world. The Ghost of Gandhi is an enduring reminder that the fight for a better world is an unfinished project, a haunting and necessary presence that refuses to allow us the comfort of believing that the struggle is over. It is a constant, spectral call to action, urging us to continue the work he started, armed with his ideals but with the painful wisdom of his mistakes.

References

Chadha, Astha. Faith and politics in South Asia: Exegesis in international relations. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2024.

Daily Herald, London. “Gandhi, the Jews & Zionism: Interview to the Daily Herald, London.” Interview to The Daily Herald, London, by Gandhi (March 1921). Accessed September 8, 2025. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/interview-to-the-daily-herald-london-by-gandhi-march-1921

Farhoud, Amira. “Interview with Dr. Mubarak Awad.” The Bethlehem Institute of Peace and Justice is a program of Bethlehem Bible College, March 2, 2024. https://bipj.org/interview-with-dr-mubarak-awad/

Fischer, Louis. The life of Mahatma Gandhi. London: Vintage, 2015.

Harijan. “Gandhi & Zionism: ‘The Jews.’” “The Jews” by Gandhi, November 1938. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/lsquo-the-jews-rsquo-by-gandhi

Khalidi, Rashid. The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A history of settler colonialism and resistance, 1917-2017. New York: Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company, 2020.

Miller, Elhanan. “What Would Gandhi, MLK, and Mandela Vote? – Fatah or Hamas?” The Van Leer Jerusalem Institute, April 22, 2018. https://www.regthink.org/en/what-would-gandhi-mlk-and-mandela-vote-fatah-or-hamas/

Reuters. “Gandhi’s ‘march Home’ Cry.” The Guardian, August 30, 2004. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/aug/30/israel

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – What If Afghanistan Had Its Own Gandhi?

- Without a Future: Gandhi, Childhood and Politics

- Towards Advocating a ‘Tradition Approach’ to Gandhian Nuclear Ethics

- Gandhi and the Posthumanist Agenda: An Early Expression of Global IR

- Ghost’s Gaze: Direwolves, War, and Interspecies Relations in Game of Thrones

- Opinion – Speaking Truth to Power in Kashmir