To find out more about E-IR essay awards, click here.

J. L. Holzgrefe claims in his “Definition of humanitarian intervention” in Cambridge University Press’s Human Intervention: Ethical, Legal and Political Dilemmas that human intervention refers to a threat or use of force by a state against another without its constant to prevent human rights violations (Holzgrefe, 8). This statement is non-controversial, but incomplete. According to Martha Finnemore, its primary goal is “not territorial or strategic but humanitarian” (Finnemore, 1), thereby contradicting the liberal and realist theories which assume geostrategic or economic interests before even considering the question of humanitarian intervention (ibid). She argues today’s definition of humanitarian intervention has not always had the same meaning (ibid). After conducting an analysis of 150 years of international politics, she concludes that the shift in the definition of humanitarian intervention correlates with changes in internationally-held norms (ibid). Finnemore addresses these changes via a constructivist approach, and claims that states’ conceptions of interest are shaped by a normative context that bends proportionally to historical alterations (3). Since norms are socially constructed, any national change in social interactions can affect them on an international level (ibid); that is, what is internationally held as acceptable can be altered, and international culture can be re-shaped and redefined according to such changes. Such phenomenon can, and did, modify international law. For instance, the legality and justifications for humanitarian intervention were revised after the events of the Second World War and in the post-Cold War era (Finnemore, 1; Kardas, 1; 4). Likewise, terms such as this of “humanity” were redefined following the abolition of slavery and decolonization in the 19th and 20th centuries (Finnemore, 10).

Finnemore also observes that the idea of multilateralism went from being a means of strategic surveillance between states in the 19th century to having a qualitative dimension based on a responsibility to protect (19). A major question arising from such a statement revolves around international culture. What makes up international culture while countries’ national cultures can part so extremely from one another? The complex system involved in international politics makes the justification for humanitarian intervention essentially controversial. States justify their interventions around shared values and expectations to rally other states to their actions, and to prove that an attack in another state is legal, legitimate, and internationally acceptable (4). One can draw out several obstacles from the necessity of justification for a state to enter into conflict with another. First, the legitimacy of its intent must be proven (13). Second, the military intervention must be multilateral (ibid). This second point understates that power and control are to be shared between interveners which “may seriously compromise the military effectiveness of [such] operations” (ibid). A third problem arising from the debate of humanitarian intervention is that even though it might not be approved by the United Nation Security Council (UNSC), some states have enough power and influence to supersede such a decision and intervene in the country they esteem needs help (Kardas, 1). The United States of America is known to have taken such measures as it attacked Afghanistan and Iraq without the legal authorization of the UNSC. Another issue humanitarian intervention poses is the legitimacy of such actions when confronted to the prevailing principle of states’ sovereignty (Weil, 3).

The purpose of this paper is to determine and analyze the processes used to justify humanitarian interventions, and to examine the extent of the authenticity of these processes in relation to international norms and morals. It tries to demonstrate that humanitarian interventions are justified if they serve a purpose which is greater than the intervening state(s)’s interest; that is, if it is done to protect internationally held norms. This paper first sheds light on the legal aspects of humanitarian interventions by examining the United Nations Charter, the various elements of international law involved in the decision of an intervention, and the factors taken into consideration as regards to the extent of human rights violations which will trigger military intervention. In a second part, this paper acknowledges the limits of the law concerning the entry into force of the United Nations (UN) articles relative to human rights violations, the International Criminal Court jurisdiction, the terminology used within UN articles, and the limits of power of the UN. Thirdly, this paper aims to convey the legitimacy of such interventions and the responsibility nations have to endorse to protect human rights, thereby justifying humanitarian interventions beyond the law. It explains the “model of pretext wars” and discusses some of the critiques made regarding humanitarian intervention. Finally, this paper exposes the UN principle of the responsibility to protect as the ultimate justification for humanitarian interventions.

The first step to determine whether humanitarian intervention is legally justifiable is to define what is considered an ‘act of aggression’ in the UN Charter. To Laurie O’ Connor, former legal scholar at the University of Otago, an “act of aggression” is one that involves the use of force by a state against another and conflicting with the UN Charter in accordance with article 8bis(2) of the UN Charter (O’ Connor, 9; “Resolution RC/ Res. 6*”, 18). Article 3 of the UN Charter lists some examples of acts of aggression as being a military invasion against another state, a blockade of harbors or strategic spots, or allowing a state territory to be used by another in the purpose of attacking a third one (Werle, 6). O’Connor draws out two exceptions to this general rule: for military intervention not to be considered an act of aggression, it must be ascertained as an international customary norm, or it must conform to the rules under the UN Charter where it can be justified if approved by the UNSC, under the chapters VII and VIII (O’Connor, 9; “United Nations”, 3314, Article 2(4)). Likewise, Article 51 of the UN Charter states that states can use military force if they are under attack as a means for self-defense (O’Connor, 10). As a consequence, humanitarian intervention could be legally justifiable if one refers to the UN Charter. However, it is interesting to note that what can be considered an international norm is fairly vague and requires one to study international law, particularly the meaning behind its concept of “internationally held norms”.

Under international law, humanitarian intervention can be justified if it combines two elements necessary to establish a legally binding custom: opinio juris and state practice (Cornell University Law School, website; O’Connor, 13). Opinio juris refers to a norm that has been held as a strong principle and rule of conduct for so long that it becomes recognized as a law within itself (ibid). Equally, state practice implies that the norm held as law must have been used as such for a long period of time, in a uniform and consistent manner (O’Connor, 13). For humanitarian intervention to be justified under customary international law, there has to be a combination of proofs supporting the state’s intent to enter into conflict with another on the grounds of international peace such as codes, treaties signed by a majority of countries, and public statements made by heads of states (Agusti, Earle, & Schaffer, 48). International law only justifies humanitarian intervention if it is multilateral; hence, it prohibits the threat to use force against another state as well as the actual use of force against it when the intervention qualifies as a unilateral humanitarian intervention (Goodman, 8; Finnemore, 13). An intervention is considered to be unilateral when a state is attacked solely by one other state, as opposed to multilateralism which supposes an attack of a state by multiple states fighting against violations of peace and human rights. In analyzing the justification for humanitarian intervention, one could wonder how states proceed in their decision of intervening in a state which violates human rights.

An attempt to answer such a question clarifies the idea of legally binding norms. In Cambridge University Press’s Human Intervention: Ethical, Legal and Political Dilemmas, J. L. Holzgrefe analyzes the concept of “social contractarianism” (Holzgrefe, 28). According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, social contractarianism refers to a political theory of authority which asserts an ideal state’s authority as originating from its people (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Holzgrefe, 28). Hence, the idea of a legal contract is implied when considering the theory of social contractarianism (ibid). This political theory underlines the fact that norms that become legally binding are based on morals and on a mutual consent between a given state and its people (Holzgrefe, 28). The UN seems to have based its rules regarding human rights violations on the political theory of social contractarianism, where member states throughout the world have a morally binding contract with each other to fight for peace and freedom. Consequently, if any state were to violate human rights as they are defined in the UN Charter, UN member states would have a moral obligation to intervene to restore peace and freedom within that state (United Nations, “Global Issues”). As of 1995, the International Bill of Human Rights counted 132 signatories, including states such as Iraq, Israel, the Islamic Republic of Iran, and Afghanistan (Fact Sheet No.2 (Rev.1), “The International Bill of Human Rights”, 6). This signifies that signatory states committing human rights violations are subject to a legal, multilateral humanitarian intervention.

One can draw out several limits to these legal aspects. Holzgrefe remarks that differences exist within the concepts deriving from the definition of social contractarianism (Holzgrefe, 29). Social contractarians argue on the identity of the parties involved in the construction of a legally binding norm. Some believe that social contractarianism occurs between a state and its people while others trust that norms become legally binding as soon as states consent to them (ibid). Such divergent beliefs can alter the very definition of social contractarianism and thus, the meaning of the concept held by the UN regarding the legality of humanitarian interventions. As Holzgrefe observes, “the identity of the contracting parties […] affects which norms would be chosen – and hence which are morally binding” (ibid). At the same time, because the law employs broad terms, some question its effectiveness and wonder what aspects are taken into account to generate a decision to intervene. In an essay entitled ‘Humanitarian Intervention as a Perfect Duty: a Kantian Argument’, Carla Bagnoli sheds light on this limit of the law (Bagnoli, 4). She states that humanitarian intervention is based on a moral case where it strives to protect the value of people’s humanity (ibid). The moral implication required by organizations such as the UNSC has to be independent from any other factors aggravating the case of the targeted state (ibid). That is, the basis of humanitarian intervention is founded solely on moral grounds which, if significantly violated, trigger an armed intervention (ibid).

The various statutes and articles related to humanitarian intervention present other limits. Following the Review Conference of the Rome Statute of 2010, articles 121(4) and (5) of the UN Charter concerning the crime of aggression read that states need to accept or ratify the amendment before it enters into force (O’Connor, 37; The International Center for Transitional Justice). However, it only enters into force one year after state parties have accepted or ratified the new statute (O’Connor, 37). Parties that did not accept nor ratify the amendment are not subject to the jurisdiction of the ICC (ibid). According to the official website of the ICC, the amendment will not enter into force before 2017; neither will it unless at least 30 state parties ratify the amendment (Coalition for the International Criminal Court). Problems with jurisdiction arise, as well. Even if the amendment enters into force, and even if the articles 8bis (1) and (2) referring to acts of aggression and to manifest violations of the UN Charter are proven, the Court needs to have jurisdiction over the defendant to justify a humanitarian intervention (O’Connor, 37). O’Connor outlines three approaches that give the ICC jurisdiction. First, she alludes to article 13(b) of the Rome Statute which authorizes the UNSC to refer an illegal situation to the ICC regardless of the state’s involvement toward the Rome Statute, if the UNSC obtains a majority of votes, including those of its 5 permanent members (40). State referrals and Proprio Motu referrals are two other ways for the ICC to get jurisdiction, but the case must meet the “Preconditions to Exercise of Jurisdiction” under article 12 of the Rome Statute (42). Although it is possible for the ICC to enforce the law and have jurisdiction over the defendants, some factors can put off humanitarian interventions.

Limits denoting from the law are multiple to the point where some may question the power of the UN to defer military interventions in situations where acts of aggressions are not considered valid under the UN Charter. A first example where the power of the UN over other states is questionable relates to the United States’ unilateral decision to invade Iraq in 2003. According the UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, the Iraq war was illegal because it was not approved by the UNSC on the grounds that an invasion in Iraq did not meet the requirements enumerated in the UN Charter (BBC News, 2004). Because the United States (US) is considered to be a state with substantial hard power, it was impossible for the UN to retaliate against the US and sanction the state as should have been the case under international law. This event brought many interrogations as to how influential the power of the UN is in deferring a state from illegally invading a country. Equally, the Russian-Georgian war of 2008 was not stopped by the UN, although talks were initiated to that end (UN News Center, 2008). The UN is considered to have failed its duty to intervene and protect human rights during the Russian-Georgian war for two major reasons: its passive role in the resolution of the conflict and its inability to cooperate with the OSCE (Muzalevsky, 33). In addition, Russia, being one of the five permanent members of the UN, exercised its veto right and was able to block peace negotiations from ending its invasion in South Ossetia (Farago, 2008).

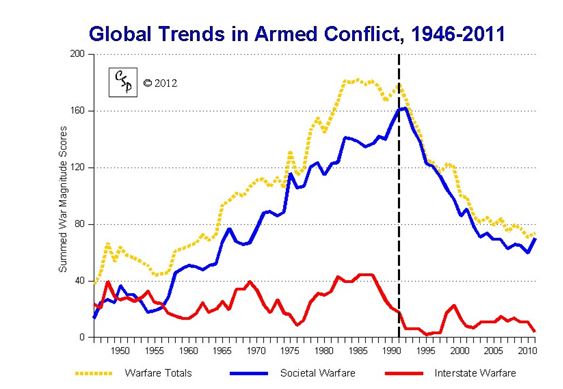

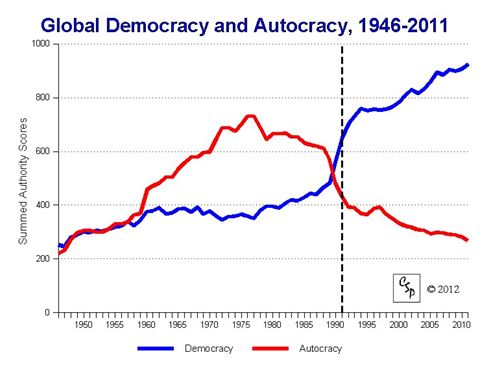

Even though humanitarian intervention has some limits in matters of law, it can be considered legitimate and can supersede the law if multilateral and based on a moral duty. Meanwhile, numerous critics attack this idea and claim that states use the concept of morality to illegally invade a country. Goodman’s “model of pretext wars” is one of the critiques (Goodman, 6). Goodman stresses that one of the reasons why unilateral humanitarian intervention became illegal was that Hitler used humanitarian motives to justify his military expansion (7). He makes a parallel between Hitler’s rhetoric and the rhetoric used by contemporary leaders to justify a humanitarian intervention (9). Hence, Goodman argues that humanitarian intervention, by legalizing some acts of aggression, alters the way states use their power (8; 9; 10). Thus, humanitarian initiatives would be used as a perfect justification for an illegal invasion, and would increase the probability of interstate war instead of diminishing it. This argument, although supported by various works (42), makes a general and bold conclusion of a highly complex process. Article 8bis (1) of the UN Charter prohibiting unilateral acts of aggression diminished the probability of interstate wars in the past 50 years. According to the Center for Systemic Peace, the amount of interstate wars declined from approximately 20 war magnitude scores at the end of the Second World War to less than 5 in 2010 (Center for Systemic Peace, Appendix A). Equally, the Center detects a negative correlation between the number of autocracies and democracies around the end of the Cold War (Appendix B). The amount of democracies increases while autocratic regimes keep decreasing (ibid).

Other critiques also question the legitimacy of humanitarian intervention. Mary Ellen O’Connell, Research Professor of International Dispute Resolution at the University of Notre Dame, argues that humanitarian intervention prolongs civil war and increases bloodshed (O’Connell, 904). She takes the example of Yugoslavia right after the independence of Croatia (909), and claims that the possibility of a humanitarian intervention slows down the process for an imminent control of conflicts (910). Because the Security Council does not legalize an intervention during civil wars unless both parties involved in the conflict accept it (912), she asserts that the time the UNSC spends over debating whether it should authorize an exceptional military intervention to stop conflicts prevents the rapid cessation of bloodshed (910). Likewise, in their paper entitled ‘Humanitarian Intervention Comes of Age: Lessons from Somalia to Libya’, Jon Western and Joshua S. Goldstein argue that one of the main flaws of humanitarian intervention is that it augments bloodshed and unnecessarily puts intervening soldiers at risk at the heart of a conflict they have no involvement in (Goldstein & Western, 51). Critics against humanitarian intervention also state that it is an incentive for rebel groups to gain more power (Nzelibe, 34; Whitty, 27). The 2003 Darfur conflict, where rebels attacked the Sudanese government, illustrates this (Whitty, 19). Rebels provoked massive massacres to attract the UN’s attention (27) and to mediatize their vindications, at the cost of millions of lives (30). In doing so, rebels hoped for their negotiating power to increase and for a gain in political power (Nzelibe, 36). Although the success of Darfurian rebels’ operation is unclear (Whitty, 30), this incident sheds light on the flaws surrounding humanitarian intervention.

Even though these critiques can be considered valid, they cannot erase the ethical argument in favor of humanitarian intervention, underlying in the concept of the ‘responsibility to protect’. The responsibility to protect was first put forth in 2001 by the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) (MacFarlane, Thielking, & Weiss, 978) and officially defined in the World Summit of 2005 (ibid). Paragraphs 138 and 139 of the World Summit document (United Nations, General Assembly, 2005) outline the main principles defining the concept. Alex J. Bellamy condensed these principles into four points. First, the responsibility to protect refers to states’ duty to protect their citizens from human rights violations (Bellamy, 623). Second, states have a duty to intervene in other states where human rights are violated, providing assistance to heads of states to build around this principle (ibid). Third, they commit to helping the populations suffering from their government’s violations in a peaceful way (ibid). Lastly, the responsibility to protect implies the right of the Security Council to use all means necessary to end human rights violations in a state, as a means of last resort (ibid). The responsibility to protect aims at the respect of human rights worldwide and allows world organizations to intervene military to reach that end. Despite past failures in the UN’s reactivity concerning the implementation of paragraphs 138 and 139 during conflicts as stated in the previous paragraph, the UN seems ready to amend the Charter to facilitate states’ responsibility to protect (Hamann & Muggah, 6).

Criticisms challenging the effectiveness of humanitarian interventions are multiple. Nonetheless, UN efforts to promote and defend peace and human rights since the end of the Second World War are endless. In spite of opposition to military interventions, experience has proven that such measures can free state populations from dictatorships and abusive government restrictions. The recent intervention in Mali by France provides a fair example of the success and prevention of a military intervention. Hence, human rights violations can justify humanitarian intervention if one can prove that the intervention is based on an ethical and selfless duty to intervene. This paper aimed to highlight the complexities involved within the principle of humanitarian intervention by shedding light on its different aspects. First, this paper stressed the factors of legality that are behind a humanitarian intervention. Second, it acknowledged limits within the law that one can encounter while referring to the UN Charter or international law to justify an intervention. Third, the paper highlighted some of the main critiques opposing humanitarian intervention and refuted them through the moral basis on which humanitarian intervention is founded: the responsibility to protect.

The issues surrounding humanitarian interventions are still very much present but do evolve. It is important to note that the concept of the responsibility to protect is a new one which needs to develop and progress so as to fit the international culture and landscape. In a 2013 report, Doctor in International Affairs Eduarda P. Hamann and Research Director at the Igarapé Institute Robert Muggah distinguish “R2P” from “RwP” (7), i.e. the responsibility to protect from the responsibility while protecting. They consider the evolution of both of them in relation to each other and provide ways in which both responsibility principles can be reinforced (8). In addition, it appears that world organizations’ goal to protect human rights is heading toward non-military interventions where sanctions and economic embargos would prevent unnecessary bloodshed. Peace talks are privileged and humanitarian interventions is only considered as a last means to stop a state from violating human rights. Thus, the mission of the UN remains the same, but the organization uses different means to prevent interstate wars before they occur.

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Works Cited

Agusti, Filiberto, Earle, Beverley, & Schaffer, Richard. International Business Law and its Enviornment. South- Western Legal Studies in Business, Academic Series: 7th ed. 2009.

Bagnoli, Carla. « Humanitarian Intervention as a perfect Duty: a Kantian Argument”. Nomos, 2004:47. https://pantherfile.uwm.edu/cbagnoli/www/hi.pdf.

Bellamy, Alex J. “The Responsibility to Protect and the Problem of Military Intervention”. International Affairs. 84: 4. 2008.

Finnemore, Martha. “Constructing Norms of Humanitarian Intervention”. The Culture of National: Norms and Identity in World Politics. 2002. http://www.metu.edu.tr/~utuba/Finnemore.pdf.

Goldstein, Joshua S. & Western Jon. “Humanitarian Intervention Comes of Age: Lessons from Somalia to Lybia”. Foreign Affairs. Vol. 90, No 6. Nov.-Dec. 2011.

Goodman, Ryan. “Humanitarian Intervention and Pretexts for War”. International Law Workshop. Sept. 14, 2007. escholarship.org/uc/item/3tw008bp#page-2.

O’Connell, Mary Ellen. “Continuing Limits on UN Intervention in Civil War”. Indiana University School of Law. Jan. 1, 1992.

O’Connor, Laurie. “Humanitarian Intervention and the Crime of Aggression: The Precarious Position of the ‘Knights of Humanity’”. University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. Oct. 15, 2010. http://www.otago.ac.nz/law/research/journals/otago036321.pdf.

Hamann, Eduarda P. & Muggah, Robert. “Implementing the Responsibility to Protect: New Directions for International Peace and Security?”. Igarapé Institute. March 2013. http://pt.igarape.org.br/implementing-the-responsibility-to-protect-new-directions-for-international-peace-and-security/.

Holzgrefe, J. L. & Keohane, Robert O. “Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political Dilemmas”. Cambridge University Press. 2003. http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/samples/cam034/2003269355.pdf.

Kahler, Miles. “Legitimacy, Humanitarian Intervention, and International Institutions”. Politics Philosophy Economics. 10:20. Nov. 29, 2010. http://ppe.sagepub.com/content/10/1/20.

Kardas, Saban. “Humanitarian Intervention: The Evolution of the Idea and Practice”. Journal of International Affairs. Vol. VI, No 2. June-July, 2001. http://sam.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/SabanKardas2.pdf.

MacFarlane, S. Neil, Thielking, Carolin, & Weiss, Thomas W. “The Responsibility to Protect: Is Anyone Interested in Humanitarian Intervention?”. Third World Quarterly. Vol. 25, No 5. 2004. http://teachers.colonelby.com/krichardson/Grade%2012/Carleton%20- %20Int%20Law%20Course/Week%207/R2P.pdf.

Muzalevsky, Roman. “The Russian-Georgian War: Implications for the UN and Collective Security”. Oaka. 2009. www.usak.org.tr/dosyalar/dergi/3Vzh20xagM2oCY3TKQKTCXHC5S3i0x.pdf.

Nzelibe, Jide. “Courting Genocide: The Unintended Effects of Humanitarian Intervention”. Nov. 2008. http://jcpa.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/courting_genocide__November_2008_- _2_.pdf.

Weil, Carola. “Legitimizing Humanitarian Intervention: From Rwanda to Darfur”. Center for International Studies, University of Southern California. April 2005.

Werle, Gerhard. “The Crime of Aggression between International and Domestic Criminal Law”. 15th International Congress on Social Defense, Presentation. Sept. 2007. http://www.defensesociale.org/xvcongreso/ponencias/GerhardWerle.pdf.

Whitty, Kelly. “Darfurian Rebel Leaders and the Moral Hazard of Humanitarian Intervention”. Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, Carleton University. Paterson Review. Vol.9. 2008. www.diplomatonline.com/pdf_files/npsia/2009/PDF%2020Kelly%20Whitty%20%20Darfurian%20rebels%20and%20moral%20hazard.pdf.

Web Sites Cited

http://unispal.un.org/UNISPAL.NSF/0/023B908017CFB94385256EF4006EBB2A

http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/opinio_juris_international_law

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/contractarianism/

http://www.un.org/en/globalissues/humanrights/

http://ictj.org/rome-statute-review-conference

http://www.iccnow.org/?mod=aggression

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/3661134.stm

http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=29356&Cr#.UXAA9uSpqSo

http://www.newser.com/story/35312/russia-blocks-un-effort-to-end-georgia-war.html

http://www.systemicpeace.org/conflict.htm

http://responsibilitytoprotect.org/world%20summit%20outcome%20doc%202005(1).pdf

—

Written by: Cecile Garrett

Written at: Centre d’Études Franco-Américain de Management

Written for: Dr. Dylan Kissane

Date written: April 2013

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Will Armed Humanitarian Intervention Ever Be Both Lawful and Legitimate?

- Linking the Diffusion of Military Ideas to Human Rights Violations at EU Borders

- To What Extent Was the NATO Intervention in Libya a Humanitarian Intervention?

- Do Human Rights Protect or Threaten Security?

- Walking a Fine Line: The Pros and Cons of Humanitarian Intervention

- Cultural Relativism in R.J. Vincent’s “Human Rights and International Relations”