The Secretary: A Journey with Hillary Clinton from Beirut to the Heart of American Power

by Kim Ghattas

Macmillan, 2013

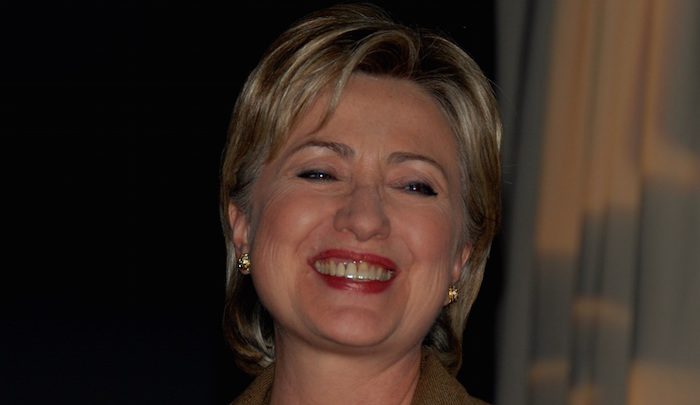

The Secretary: A Journey with Hillary Clinton from Beirut to the Heart of American Power (2013) is a unique look at world events from 2008 to 2012 through the lens of a Lebanese journalist, author Kim Ghattas, who grew up questioning American power. Ghattas was raised in Beirut during the Lebanese civil war. In 2008, she became the State Department Correspondent for BBC News, the only non-Western journalist in the State Department press corps, and moved to the U.S. She traveled with U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, observing and reporting on American foreign policy. Her personal journey from “Beirut to the Heart of American Power” coincided with Clinton’s journey from former First Lady, U.S. Senator for New York, and defeated presidential candidate to America’s ambassador to the world, during a time when America was seeking to re-build its image under a new President. In The Secretary, Ghattas seeks to take the reader on this journey on each of these three levels: her personal journey, Clinton’s journey, and the journey of improving America’s image. She weaves this multi-layered narrative well, and reveals some startling truths along the way. Her conclusions, however, don’t live up to the power of the narrative.

Ghattas was raised in a world where America was seen as omnipotent and all powerful. She opens the book with these words (pg. 1): “I grew up in Beirut, on the front lines of a civil war. My father always said, “If America wanted the fighting to end, the war would be over tomorrow.” He waited fifteen years for the guns to fall silent.” Her father’s view is not without merit.

World War II and the Marshall Plan created an international image of the United States as an all-powerful nation builder. The U.S. proved its military skill and force by routing the Axis powers on two fronts and effectively winning World War II for the Allies. After the war, the U.S. re-built Europe under the Marshall Plan. This set a precedent – get America involved and you will win your war and it will re-build your country. In the decades to follow, the U.S. orchestrated the ousting of dozens of foreign leaders, operations popularly known as “covert foreign regime change actions”, including Syria, Iran, and Turkey, all neighbors of Lebanon. Many of the people that witnessed this demonstration of power believed that if a country’s fate is tied to the U.S., the U.S. must spend a great amount of time considering that country. Ghattas finds this is not true when she is introduced to “the book” – a briefing book created for Clinton by her staff before she visited a country, which was cast aside after the visit ended. One of Clinton’s aides, Vali Nasr, reflected on this after a trip to Pakistan (pgs. 99-100):

This was a sobering moment – one book shut, one book opened, one country down, another to go – barely any time to think or reflect. “If only people on the ground could see that,” Vali thought as he watched the others passing around notes and making calls to Washington and Abu Dhabi to prepare for their arrival. “Every country believes that the United States sleeps and wakes up thinking about them and just them. They’re just a tiny speck on a map.” Just a few pages in a big book.

This is a major aspect of Ghattas’s journey, one that is repeated throughout the book. The U.S. has an image as an omnipotent superpower, but in reality it cannot be equally involved in the fate of every country in the world. Nor does it want to be.

The Obama administration emphasized this in other ways as well, seeking to withdraw from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and implement “smart power” in foreign policy. Ghattas explains (pg. 11): “Not just soft diplomacy, with a focus on development or just hard military power, but a combination – an updated, global version of the Marshall Plan.” And (pg. 38): “…power through military might alone was too expensive and no longer sufficient to remain relevant in a world that was changing so quickly.”

With her background, Clinton was in a unique position to implement this strategy. Many of the leaders she met with as Secretary of State were old friends from her days as First Lady. Clinton also built on her experiences in the Senate where she served on the Committee on Armed Services (2003–2009) and was a member of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (2001–2009). She understood the necessity of improving America’s image after the George W. Bush administration, and also the delicate balance between military intervention and diplomacy. This point is emphasized by Ghattas. Clinton had experience in world affairs but had never been given a major role before becoming Secretary of State. Now she was the face of American foreign policy, and the Obama administration. It was her responsibility to improve America’s image using smart power and she was excited for the task. This strategy and Clinton were tested in 2011 during the Arab Spring.

As popular uprisings spread throughout North Africa, the U.S. had to decide whether to intervene in Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, and Syria. Each country had a different revolution scenario and the U.S. approached each one differently. In Libya, Clinton pushed for military intervention. The U.S. engaged in air strikes which dragged on for months before Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi was finally killed by revolutionaries. Ghattas was visiting Lebanon during that time and had a revealing conversation with a childhood friend (pg. 277):

“But what do you think they have planned, you know, for Lebanon, for Syria?” Randa asked. I looked at her, eyebrows raised. “Plan? Randa, there is no plan. You know, Americans are trying to figure this out day by day and manage it as best they can.” A look of horror descended on her face. She raised her hands in the air. “Kim, Kim! What are you saying? What do you mean there is no plan? If the Americans don’t have a plan, then who the hell is in charge of everything?”

It is at this point that the book reaches its zenith. Ghattas has shown the reader her arc and her new understanding of American power, and she has done it well. She has woven personal anecdotes into the fabric of world events and made the dynamics of American foreign policy relatable to the reader. The U.S. is a super power but it is not omnipotent, nor is it consistent. Its policies change when the administration changes. The policy of the Obama administration is smart power and less military intervention, and Clinton has come into her own enough to push for military intervention in Libya while recommending alternative options elsewhere.

Then U.S. compounds in Benghazi, Libya were attacked on September 11, 2012, and American Ambassador John Christopher Stevens was killed. This was a turning point in Clinton’s legacy as Secretary of State, and a true test of whether her work to improve America’s image was sustainable. Unfortunately, Ghattas provides only a cursory analysis of this critical event and concludes that (pg. 335):

Ever the politician, Clinton managed to dodge most of the acrimonious attacks. By the time she left office, Clinton had traveled a million miles, rebuilding her country’s image with her relentless public diplomacy and quietly reasserting American leadership.

Following that, Ghattas ends the book with a few brief remarks. As a reader, I felt the end was a disappointment, leaving key issues unresolved. Ghattas did such a superb job weaving the three journeys that I was excited for a resolution; a multi-layered conclusion that would bring the journeys together and explain their relevance now. Instead Ghattas’s final chapter seemed hastily done, lacking the careful reflection evident in earlier chapters. With a potential presidential run in Clinton’s future, an examination of her approach to foreign policy is timely. If you’re looking for a review of Clinton’s actions during her tenure as Secretary of State, then this book is an excellent read. The ultimate meaning of those actions, their impact on the future of America as a world power, and how they could forecast Clinton’s actions if she is elected President, is something you’ll have to interpret for yourself.