Max Weber brilliantly demonstrated the impact of religion and culture on politics, and even on world-scale institutions, at the beginning of the 20th century in his famous work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. A single religious idea, a theological principle, through a causal chain that Weber eloquently demonstrates, led to the establishment of modern, rationalized capitalism. Modern, rationalized capitalism, for Weber, was a particular form of capitalism to be distinguished from what he calls “traditional capitalism”. Modern, rationalized capitalism was characterized, for Weber, by an emphasis on constant production linked with worldly asceticism. Worldly asceticism, likewise, was made up of various factors, including: frugality, wealth accumulation, and various forms of (especially economic) self-abnegation. The (economic) self-abnegation implied abnegation of one’s family as well, as applied by a “responsible” adult (assumed to be a father in those cultural contexts). And, all of this, from the single religious – theological – notion of “the Calling”, as understood by John Calvin, and as mediated into cultural systems through the interpretations of specific communities in Europe and North America.

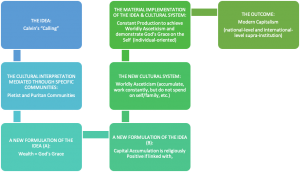

How does the causal chain work for Weber? Basically, like this:

The Protestant Ethic Causal Chain (causal schema is original to Patricia Sohn)

It short: it is okay, and even religiously positive, to accumulate as much wealth as you can as long as you self-abnegate. Just do not spend it (on yourself, your spouse, or your children) and you will be fine.

I am in no way advocating this position. In fact, I think that it is completely backward, morally, ethically, and – probably, in terms of God’s Grace!

Let me make a case for Traditional Capitalism. According to Weber, traditional capitalism was that capitalism more characteristic of Catholic societies in Europe in which one worked to maintain one’s chosen standard of living, where one was most comfortable. Rather than striving constantly to accumulate surplus wealth – more than one would need or be allowed, in terms of forceful social pressures, to spend – traditional capitalism involved striving for some periods, and spending long periods in quality time with one’s spouse, children, and extended family. It was also, typically, tied with large extended family units such that the striving to maintain the standard of living of one’s family was not a burden carried by only one or two people (in what Durkheim calls the “conjugal” or nuclear family), but, likely by several dozen people or more.

“Traditionalism”, that term maligned and beleaguered by modernization theory, begins to look a lot like “post-materialist values” when laid out in some of its everyday details. If one wanted to increase one’s standard of living in that period, one was free to head on to the Silk Route and be on the road for some years in order to do so. But if the open road was not appealing, having time for weekday lunch with the family, chess and tea in the afternoons does not sound so terrible. In fact, it reminds me of sheshbesh and sahlab on the Red Sea, or anywhere in North Africa. Keeping up with the painting on the walls and window sills can wait for a few years here and there in exchange for such freedom. It is all about priorities and accepting imperfection in some areas in exchange for freedom and quality of life.

Both freedom and quality of life defined are differently by different peoples. For modernists in the U.S., they seem to be defined, most often, in terms of having excess capital to spend. For much of the world – and I am thinking here of Africa, the Middle East, parts of Asia, parts of the Caribbean and Latin America as well (e.g., much of the world) – both freedom and quality of life may be defined more in terms of Time. That is, the freedom to set one’s own schedule, the freedom to spend quality time with one’s family, the freedom to have time to cook delicious meals, all of these are more substantive freedoms for some people than are the “freedoms” offered by cold, hard cash.

Post-materialist values suggest that we choose “quality of life” over dollars, at least in relation to increasing numbers of issues. Quality of life is precisely one of the prime goals of Traditionalism, and of traditional capitalism, in as much as it was intended to uphold one’s freedoms to decent housing, enough food, and enough time to enjoy both of those and family. It is worth noting that traditional societies rarely demonstrate the same distorted and, even, at times, pathological social behaviors among families that are epidemic within societies characterized by modern, rationalized capitalism.

We are getting somewhere in choosing post-materialist values over modern, rationalized capitalism. We are coming closer to Traditionalism and to some of the wisdom of parts of the Old World, which tended to maintain a focus on quality over quantity, and which did not posit meaningless (and, at times, cruel) abnegation of the self and the family in service of an existence better defined by Scrooge than by any positive models of this worldly existence as striving for something holding paradise as its prototype.

The greatest difference that I have observed, as a political ethnographer, between Old World Orthodoxy (across religions) and modern New World secularism is that the former continues to strive to make this worldly existence into something modeled on paradise in small ways and large on a daily basis; whereas, the latter has resolved that this world is meant to be hellish, brutish, etc., and moves forward full-force to make that happen in practice on a daily basis.

I offer, instead, Traditionalism, or pre-modernism, which looks an awful lot like post-materialist values, as a viable way for religious and non-religious people alike to strive for the former rather than the latter.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Future of Popular Geopolitics: Zombie Evolution and the Return to the Social

- Adorno on Late Modernity and Unfreedom: Reflections in a Global Era

- Reinforcing Environmental Degradation With Market-Based Sustainability Schemes

- Opinion – Thinking about Heroes and Humanity During COVID-19

- J’accuse! The Case for Pre-modernism, or, the Rural-urban Divide

- Ukraine War: The Limits of Traditional Naval Power and the Rise of Collective and Civilian Seapower