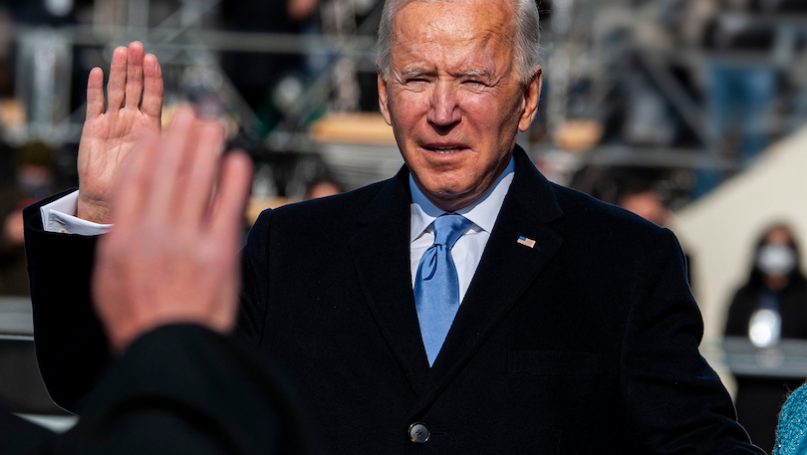

For many regions of the world, the election of President Biden signals a welcome resumption of American global leadership. Under President Donald Trump, America had stepped back from the world and its proactive commitments to international cooperation, in forums such as the United Nations, NATO, and the World Health Organization (WHO). Trump’s ‘America First’ policy, and bombastic style, often conducted via social media, had undermined a number of key relations with allies and forced a reassessment of the longevity of American power. In January, those harbouring hope for a shift in US engagement appeared vindicated by a flurry of major announcements from the new administration, from re-joining the Paris Climate Agreement to breathing new life into the JPCOA with Iran.

In his first major foreign policy address, delivered at a State Department side-lined over the preceding four years, President Biden had a clear message: ‘America is back’. There would be more support for diplomacy, and diplomats, and efforts to repair the bonds that had been strained. The task of leading this re-engagement now falls to the newly confirmed Secretary of State Tony Blinken, who embodies much of the experience, expertise, and empathy that is required to signal the sincerity of America’s commitment to diplomacy. His nomination and Senate approval – including by the majority of Republican senators – is a step in the right-direction to re-establishing the international credibility of US diplomacy.

Whilst the US has some of the world’s biggest and best resourced diplomatic levers, it cannot address global challenges alone, nor should it try. As Blinken pointed out during his Senate confirmation hearing, ‘‘the world does not organise itself’. Instead, the American diplomatic renaissance must embrace and exploit the many forces shaping an increasingly fractured world order, and learn to listen and cooperate rather than just lead.

Re-engaging will require the US to recognise it strengths, and to accept its limitations. There can be little doubt over the harm done to America’s international standing under Donald Trump. Trust in the integrity and durability of American values-led engagement has been eroded, and proven fragile. Too often, ‘America first’ has meant ‘American alone’, as the US neglected alliances carefully cultivated by generations of statesmen since the end of the Second World War. Whilst Trump is not singularly responsible for a lack of humility towards allies and adversaries alike, he often exceeded the bounds of tolerance.

Recommitting to multilateralism is essential. But it requires humility and an ability to listen to, and seek to understand, the needs and interests of other states and non-state actors in the system. Over the past year, the pandemic has brought home the inescapably interconnected nature of today’s world and demonstrated that even great powers can do little in isolation. Few would disagree that cooperation is essential to everything from trade to terrorism, and from climate change to COVID-19. To regain the mantle of leadership, the new administration must persuade both its allies and adversaries that not only was its predecessor an anomaly, but that it has learnt the lessons of American excess, without adding to the very real divisions that threaten American domestic unity.

As a sign it is trying to move with the times, Secretary Blinken has pledged to rebuild and re-energise the State Department to ensure it is more representative of the American public it serves. This means not only striking a fairer gender balance and employing more people of colour, though essential. But also, taking on the challenge of making American diplomacy more representative of American public opinion and accessible to a population that is frequently ambivalent, and often divided. This is no easy task in a nation where most Republicans oppose the new administration’s re-engagement in the Paris Agreement.

Ensuring foreign policy enjoys broad public support is nothing new in any country. But Blinken takes the helm at a time when the practice of diplomacy has never been more visible to the public, and where the number of actors able to influence diplomatic relations have never been higher. Activists are prominent and vocal parts of the international community, advocating on a diverse array of issues with significant popular support. Greta Thunberg has become synonymous with the issue of climate change, with a global audience of almost 5m people just a tweet away – 1.5m more than President Biden’s Climate Envoy and former Secretary of State John Kerry.

In such an environment, formulating a coherent – and strategic – foreign policy is an unenviable task. Diplomats are subject to mounting criticism on social media if they fail to comment swiftly on issues of public interest. Worse still, they can appear to be following events, rather than shaping them. The requirement for diplomacy to be accountable is to be welcomed, but with caution. Diplomats and policy-makers have to avoid solely reacting to everything without a more substantial and coherent strategy to underpin longer term change. Formulating an appropriate response to issues still requires consultation – within governments as well as with allies and adversaries – something that takes longer than drafting 280 characters.

Our modern world presents a challenge for diplomatic practice, which can all too often appear outdated, outmoded, and detached. Yet diplomacy has never been more vital to our collective security and prosperity. Our experiences of the pandemic have demonstrated the enduring centrality of diplomacy. Already we have witnessed an unprecedented degree of international coordination, from sharing life-saving data on transmission rates to the development, testing, and distribution of vaccines. Whilst, also experiencing the challenges, from the power of nationalism, and claims of sovereignty and borders to limit supplies and access to valuable health solutions, especially from poorer countries.

The question, therefore, is how can diplomacy adapt to the complexity of modern international relations? How can it respond to the ever-growing chorus of voices and to the weakening distinctions between hard and soft power, between war and peace, and between official and unofficial diplomatic actors? This question has prompted us to unite over twenty experts to offer their views of how – and in what ways – the theory and practice of diplomacy should adapt. Over two volumes, the authors bring their insights and original research to offer new perspectives and innovative ideas to these questions, reflecting the richness and breadth of studies on diplomacy. Many of the contributors have professional experience at the heart of governments, departments, and institutions, around the world. As such, they combine theory with practice to make the case for the enduring significance of diplomacy to meet the current challenges in international relations.

For those of us who believe in the power of diplomacy, the past four years have taught us some important lessons about its potential and its limitations, perhaps most notably that we should never take it for granted. Time will reveal whether Biden can repair what has been damaged. But for America’s diplomatic renaissance to succeed, it needs a more cooperative and open approach to the world, and a reinvigorated State Department must seek to be an agent of modernity and inclusion, as well as influence. Such a challenge is not America’s alone. In the coming years, the diplomacy of many states will be tested by a multitude of factors, including the evolution of technology, the power of non-state actors, the legacy of COVID-19, nationalism and populism, and continued conflicts and tensions around the world. The imperative for diplomacy and diplomats alike to remain adaptive and proactively engaged with the shifting sands of international relations, is a timeless and universal quest.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – The US-Japan Alliance Continues to Stand for Democracy, Despite a Role Reversal

- The Mindful Diplomat: How Can Mindfulness Improve Diplomacy?

- Tech-Diplomacy: High-Tech Driven Rhetoric to Shape National Reputation

- Do Leader Visits Still Matter? Reflections on a Remarkable Week in Global Diplomacy

- Xi Jinping’s Civil Diplomacy Initiative: Origins, Purpose, and Challenges

- US-Israel Tech and Business Bonds: Advancing Innovation for Mutual Benefit