The concept of Tech-Diplomacy involves a nation strategically engaging with technological stakeholders for diplomatic objectives. Traditionally, this practice entails managing relationships and fostering ongoing dialogue between two key entities: the public sector, representing the state, and the private sector, representing the technology industry. As outlined by Ittelson and Rauchbauer (2023), Tech-Diplomacy is an emerging field in international relations and diplomacy, aiming to facilitate dialogue between states and the tech industry. This initiative has gained prominence due to the increasing influence of tech companies beyond national borders, as these entities play a significant role in shaping global dynamics. The primary focus of Tech-Diplomacy is inward, seeking to bolster the nation’s standing and promote the growth of its domestic private industry. Representatives work closely with tech entities, both within and outside the state, employing diplomatic efforts to establish mutual interests (Buckup and Canazza 2023; Höne 2023). Today, however, in the realm of technology and innovation, nations can employ not only practical engagement with tech representatives but also the power of discourse (Griset 2020). In essence, nations can use rhetoric tools to articulate and emphasize the image of technology, contributing to diplomatic endeavors.

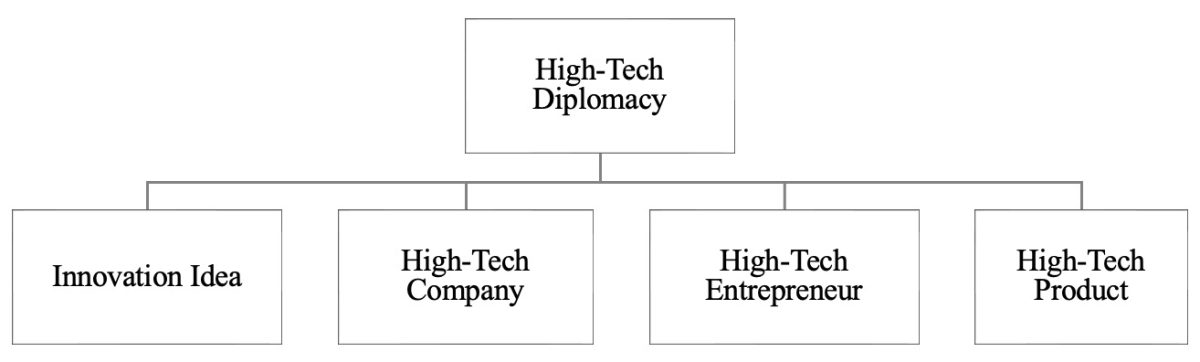

This article aims to highlight the outward-facing dimension of high-tech industry, projecting the nation’s image on the global stage. Tech diplomacy, as explored in this essay, encompasses the collective communication actions a country takes to leverage its technological assets for the purpose of shaping its international image. Indeed, diplomacy practitioners are in a constant look for innovative channels (Melissen, 2016). This particular variant of tech-diplomacy is innovative, since it relies on storytelling about a multitude of tech products, tech companies, and tech entrepreneurs to serve the country’s interests globally in interactions with other nations. The essay first delves into the etymological evolutions in the tech and diplomacy fields, illustrating the distinctions between public diplomacy and tech concepts. Subsequently, it explores four different components through which nation representatives can employ rhetoric in tech diplomacy: innovation ideas, high-tech companies, high-tech entrepreneurs, and high-tech products.

Etymology and prior tech-related diplomacy theories

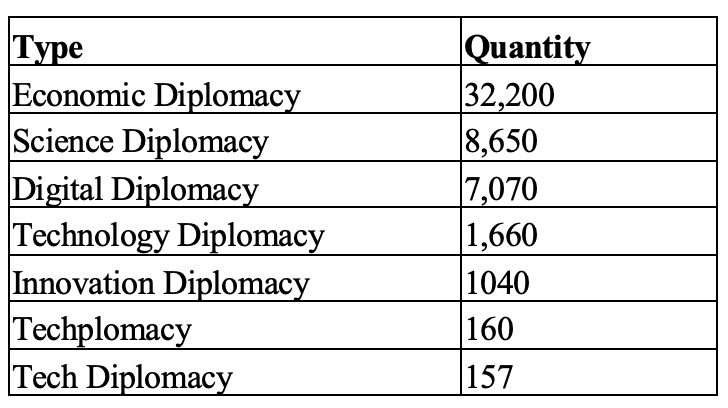

Diplomacy, historically rooted in direct leader-to-leader dialogues, has evolved with the increasing influence of technology in recent decades (Berridge 2022; Murray et al. 2011). Modern approaches, facilitated by technology-mediated channels, have become prominent in diplomacy field. Table 1 (see below) highlights the exploration of specific theories in academic literature on public diplomacy, particularly in relation to technology and economy. A search on Google Scholar, a major academic database, reveals thousands of papers examining various diplomatic tools. The theories in this table underscore a robust connection to the technological discourse discussed in this article. The terminology used reflects synonymous connotations with a technological focus, emphasizing aspects like economy, progress, and innovation. From traditional theories such as economic diplomacy or digital diplomacy to emerging ones, the diverse range of terms, as highlighted in a previous study on technological undertones, all share a common thread linking them to the technological domain. The most prevalent and expansive theory highlighted is “Economic Diplomacy” (Saner and Yiu 2003; Rana 2007). Economic Diplomacy strategically deploys financial tools to achieve a nation’s foreign policy goals, encompassing providing economic support for development or imposing sanctions to further national interests or assert influence (Bayne and Woolcock 2017). Intimately tied to soft power, Economic Diplomacy extends prominently into the tech field, utilizing various strategies to promote economic growth, cooperation, and geopolitical influence, establishing the economic outcome as the foundation for subsequent diplomatic concepts.

Over time, a concept has emerged that intertwines economic and scientific elements, recognizing the significant influence of both science and economics on people’s lives. Nations strategically utilize these realms as diplomatic instruments. The second concept discussed in the academic literature is “Science Diplomacy”, which acknowledges the role of widespread scientific collaboration and advancements in international relations (Sunami, Hamachi, and Kitaba 2013). Since “Many have drawn parallels between science diplomacy and tech diplomacy” (Ittelson and Rauchbauer 2023, 7), some argue that this is an umbrella term of a broad filed in diplomacy field. Leijten (2017, p.1) stated that “science diplomacy is often conceived as the use of the “soft powers” of scientific collaboration to smoothen the political relations between two or more nations”.

As shown in Table 1, the next popular theoretical and practical concept in public diplomacy literature is “Digital Diplomacy”, which involves using digital platforms for the distribution of diplomatic-oriented messages, such as on Facebook, Twitter, and other technological channels (Lichtenstein 2010; Feijóo et al. 2020). The study of digitalization in diplomacy is widely researched, as the expanding array of digital tools significantly influences the work of diplomats (Manor 2019). This idea is primarily dealing with ״the digital tools countries use to carry out dialogue and achieve their aims, as well as the issues those tools throw up, including privacy, cybersecurity threats and cross-border data flow” (Buckup and Canazza 2023).

Etymology wise, we can recognize in the academic literature few very similar concepts: “Technology Diplomacy”, “Tech-Diplomacy” (Buckup and Canazza 2023; Höne 2023) or in short as some called that “TechPlomacy” (Klynge, Ekman, and Waedegaard 2020). Largely speaking, both deal with advance tools that intend to bring prosperity to society, and the usage of nation in these tools for diplomatic efforts and goals. The broad idea of “tech” is also closely associated with the digital field, and it’s also linked with the previous field of science (Blume and Rauchbauer 2022). It’s worth noting that the expansive term “technology” has its roots in Greek. “Techne” signifies skill or art, while “logia” denotes study or science. According to dictionary explanations, technology encompasses the practical application of scientific knowledge (Simpson & Weiner, 1989). In fact, from etymology point of view, “Science” and “Technology” are interconnected, often found in papers dealing with both concepts simultaneously (Moosavi-Movahedi and Kiani-Bakhtiari 2012; Simelane 2015). According to Sunami, Hamachi & Kitaba (2013), Science and Technology diplomacy (S&T) are bases upon research and development (R&D). Ittelson & Rauchbauer (2023, p.7) stated that “In academia, ‘tech diplomacy’ is defined as a section of science diplomacy, digital diplomacy, or economic diplomacy”.

Yet, some tech-diplomacy, a relatively new concept, became the basis for development for new etymology in the field of diplomacy. One interesting and was generated by Denmark in the 2018. Horejsova, Ittelson & Kurbalija (2018, p.6) said:

They call this technological diplomacy – or TechPlomacy in short. The Danish TechPlomacy experiment is the result of a deliberate innovation process effort within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where a group of officials were asked to come up with ideas for the future of diplomacy, including ways of dealing with technological advancement and disruptions.

By speaking of technology etymology and diplomacy, it is only logical to add here another related idea in public diplomacy literature: “Innovation Diplomacy”. This involves deploying an array of state tools to advance national innovation interests on the global geopolitical stage (Miremadi 2016). Leijten (2017, p.3) argues that “it involves the use of diplomacy to facilitate innovation and the use of innovation to improve the relations between countries.” According to Griset (2020, p.393), Innovation Diplomacy combines “the level of discourse as well as at the level of action”. “Innovation,” much like “technology,” is a broad concept that countries can leverage for practical partnerships and image-building on the global stage. After several decades of research, it has become evident that theories in these advanced domains often share similar descriptions and nomenclature. These interconnected theories share a common objective: enhancing a country’s foreign relations through advanced, tech-savvy, and innovative tools. The effort to define these “new” diplomatic concepts has been influenced by the global enthusiasm for innovation and technology, leading scholars to explore related but distinct scopes, such as “tech diplomacy.”

Blume & Rauchbauer (2022, p.104) define tech diplomacy as the practice where “governments are sending diplomats to lobby for the interests of their citizens to the technological centers of influence”. However, it’s noteworthy that the concept of “tech diplomacy” is relatively sparingly mentioned in Table 1. To our current knowledge, it remains unclear whether this is a genuinely novel theoretical concept or perhaps just an alternative term for “technology diplomacy” with slight adjustments since technology is such a broad and abstract idea (Salomon 1984). Hence, this brief article proposes an alternative perspective for both research and practical application, rather than defining theories from the expansive viewpoint of “technology” as an abstract term, the suggestion is to scrutinize it through the specific lens of a country’s internal high-tech industry. Specifically, this involves adopting tech rhetoric and channeling it for marketing-reputation-diplomatic purposes, a practice that we will further explore now.

High-Tech Diplomacy Components: Name-dropping and Stakeholders

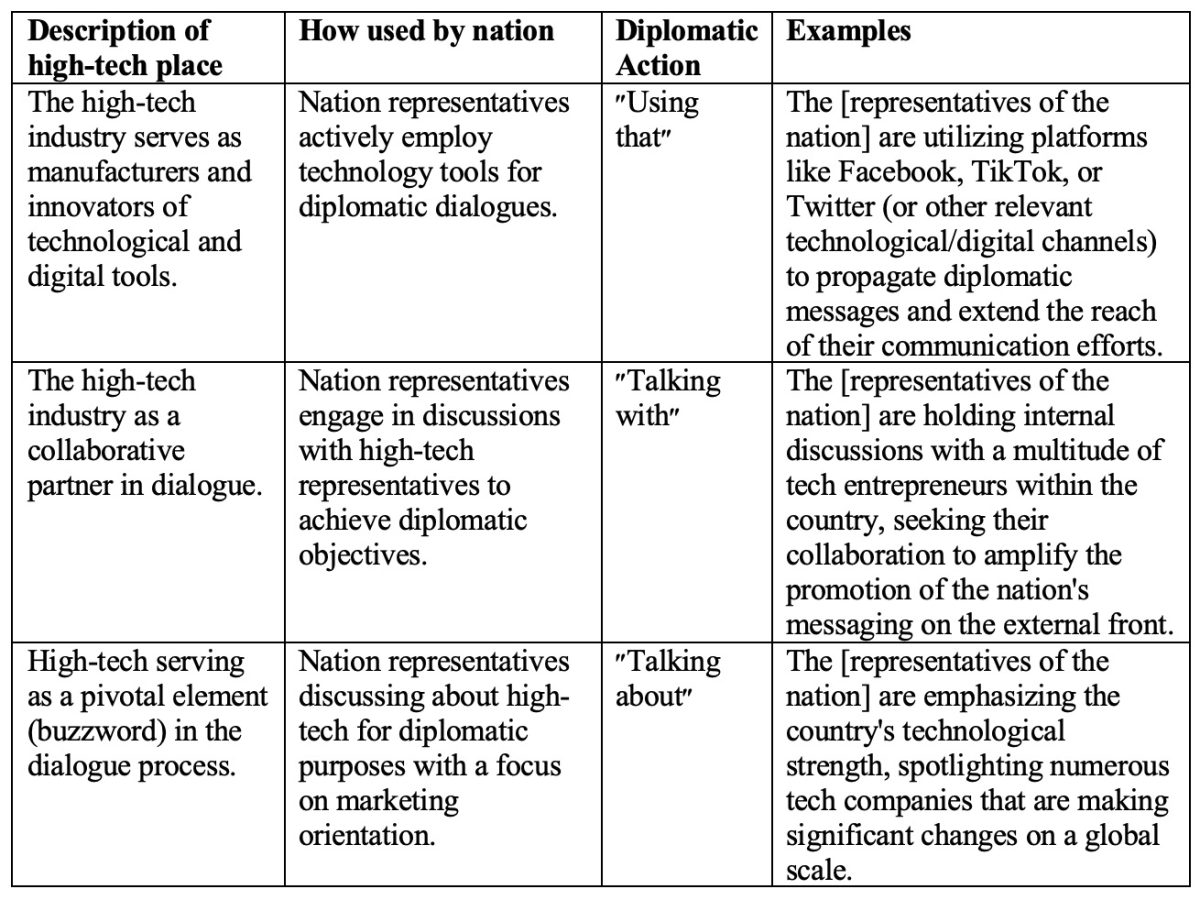

In the technology filed, there are two main categories, “low-tech” and high-tech”. Among the two, “high-tech” is the one seems to be more frequent, and cultural glorified (Mashiah 2022). Wolf & Terrell (2016) note that the high-tech industry is distinguished by a significant presence of employees engaged in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) occupations. Globally, the high-tech industry and its workforce have been undergoing rapid transformation for many years, exerting a substantial influence on various aspects of people’s lives worldwide (Aydalot and Keeble 2018). In the present context, the impact of high-tech extends beyond the confines of a nation’s economy, education, and culture, reaching into the international and diplomatic relations of nations (Höne 2023; Buckup and Canazza 2023; Klynge, Ekman, and Waedegaard 2020). By a concise overview of the pivotal role played by this industry in both the theoretical and practical realms of public diplomacy, we provide a clear and simple differentiations in Table 2. Largely speaking, up until now in tech diplomacy, nation representatives could potentially “use” technology or “talk with” technology factors. Now it is time to develop additional important layer of how nation diplomacy representatives can simply “talk about” technology for global reputation management.

Cutting-edge technology plays a crucial role in certain countries, establishing a strong and conceptual bond with the geographical surroundings where it originates and evolves. Despite this inherent connection, there appears to be an unexplored element missing in the puzzle that could successfully create a meaningful diplomatic relationship between the industry and the state. Since a significant portion of diplomatic efforts involves discourse, discussing technology becomes essential for diplomatic and reputation management reasons. However, the question remains: How can nations engage in such discourse, and what strategies can they employ to orchestrate their technological image effectively?

One potential bridging approach involves the strategic use of “name dropping.” This practice entails incorporating recognizable brands and names into texts, aiming to establish a connection with the target audience. By leveraging the familiarity associated with well-known entities (Craig, Flynn, and Holody 2017; Gooden 2015), this technique fosters a sense of identification. The incorporation of diplomats, influential figures, or entities in the field creates a cascade of ideas for self-marketing purposes. Aligning oneself with influential individuals has been shown to enhance perception and self-esteem (Campbell and Crist 2020; Twenge and Campbell 2009). In the context of nations, representatives or diplomats strategically reference well-known tech brands or personalities associated with their country, a phenomenon akin to personal name dropping. The objective is to leave a positive impact during diplomatic exchanges, positioning the nation as a hub of technological advancement and innovation. By employing this name-dropping strategy, the goal is to instill a sense of superiority and bolster the nation’s status by linking it with cutting-edge technology and forward-thinking ideas. Referencing Figure 1, the subsequent sections will illustrate how state officials using name dropping in connection to the high-tech industry and its various components can be advantageous on the diplomatic stage.

Innovation Idea

The primary approach in Tech Diplomacy centers around utilizing the concept of innovation to achieve the country’s marketing goals. In this tactic, governmental stakeholders strategically integrate expansive terms related to technology, science, and research and development (R&D) into worldwide public campaigns (Vaughan 2013). The foundation of this approach lies in the belief that these terms hold a positive social perception, and in today’s society, technological innovation is widely recognized as a force for good (Salomon 1984).

This strategy involves adopting the prevalent terminology within modern technology or specific sectors (like artificial intelligence or cybersecurity). It entails discussing technology within the broader context of the state and showcasing tangible examples of the state’s initiatives in the technological domain. Over time, countries that incorporate these technological concepts into their diplomatic narratives can present themselves as dynamic, innovative, and progressive entities of global importance. This narrative serves to highlight the country’s significance in addressing global challenges, utilizing its technological capabilities to make a meaningful impact on a worldwide scale. The strategic deployment of technology enables these nations to position themselves as contributors to global solutions, emphasizing their role as valuable players on the global stage.

Tech Company

Previous attempts to define traditional “tech diplomacy” primarily concentrated on the state’s interactions with technology companies within its borders, emphasizing the dialogue between the government and these technological entities (Buckup and Canazza 2023; Höne 2023). However, a novel definition now requires careful consideration, one that scrutinizes how the state utilizes these companies for marketing purposes (Mashiah 2022). This entails the state engaging with external parties using data and characteristics of technology firms within its borders, establishing a direct link between the state and these private sector entities on global platforms for image and advertising purposes. For example, in Israel, where there is a multitude of tech companies ranging from startups to established corporations, state officials aim to showcase a vibrant technological ecosystem by highlighting specific companies (Mashiah and Avraham 2019). This narrative involves presenting the nature of these companies, their innovations, and developments. The underlying belief is that portraying technology companies positively significantly contributes to enhancing the country’s image on the global stage.

However, despite the positive aspects and image benefits, there are potential challenges associated with this strategic alignment with technology companies. This close association can lead to crises, particularly when companies linked to a country encounter issues or if the technology developed within a country’s borders negatively impacts another nation. Essentially, when a country becomes closely identified with a specific technology company, it can enjoy the benefits of an enhanced image, positioning itself as advanced and progressive. However, this association can also lead to global crises, especially when the affiliated company faces a crisis. To illustrate this concept with the earlier example of Israel, the case of the NSO company exemplifies the potential pitfalls. As a developer of spy technology, NSO has been linked to negative events in the past, resulting in the State of Israel becoming unavoidably entangled in a negative discourse due to its association with the company.

Tech Entrepreneur

In the high-tech industry, the significance of tech employees and factors is crucial (Klepper 2001). Workers oriented towards technology hold a distinctive position in society (Hadlock, Hecker, and Gannon 1991). As a result, tech entrepreneurs and experts from various nations can play pivotal roles in the realm of Tech Diplomacy. Countries can strategically engage these individuals from the tech sector to represent and promote the nation in relevant forums. Given that technological entrepreneurs are often spread across diverse locations due to their professional responsibilities, they naturally become de facto ambassadors for their companies. In doing so, they actively market not only their products and services but also project a positive image of their home country. Consequently, governments can strategically seek the support of entrepreneurs as part of their diplomatic initiatives, contributing to the advancement of national interests.

This approach serves as a valuable asset for the state, as private-sector representatives find themselves at the interface with influential figures in the domains of economics and technology. The pivotal question is: What motivates a technological entrepreneur to actively participate in diplomatic endeavors? The state must discern compelling motivational factors that can attract entrepreneurs during critical moments. Additionally, recognizing that entrepreneurs harbor a long-term interest in cultivating their professional image, it becomes evident that their involvement in diplomatic activities can also serve to enhance their standing and contribute to the long-term success of their companies.

In essence, as part of a tech diplomacy strategy, a nation can seek to enlist technological ambassadors to convey its message. Another approach within this framework involves crafting narratives around these individuals. In this scenario, officials in the country can actively share stories about the entrepreneurs within its borders. This method offers a level of ease for the state, as the narrative is controlled directly by the state and its representatives. Ambassadors, presidents, or prime ministers can strategically weave narratives about prominent entrepreneurs, contributing to the effort of showcasing the country’s technological prowess. It’s crucial to acknowledge that both of these techniques hold significant importance in shaping the national image and positioning the country as technologically advanced. However, as with the previous strategy, it is imperative to be cognizant of potential challenges. When an entrepreneur faces a crisis, there is a risk that it may cast a shadow on the country’s image, particularly when the individual is closely associated with that nation. Hence, careful consideration of potential pitfalls is essential in implementing these diplomatic strategies.

Tech Product

In the realm of tech diplomacy, any tech entity strives to develop, build, and distribute innovative products and services (Bacon et al. 1994; Fontana and Nesta 2009). In this context, one significant aspect involves both the discourse level and the practical applications of these technologies. As observed earlier, prior theories in public diplomacy, particularly “Digital Diplomacy”, predominantly focus on how nations use technological platforms for diplomatic purposes, indicating an overlap with the current component of tech diplomacy. However, existing theories lack a specific emphasis on tech-oriented discussions at the discourse level. Tech diplomacy, therefore, serves as a promising avenue to establish a mechanism for discourse about tech-driven products by countries. It becomes crucial to develop a marketing approach that equips country representatives with information about specific significant tech solutions developed within their borders.

In diplomatic efforts, representatives can leverage narratives about these products to showcase broader technological achievements. Tech products and services that significantly impact global society become valuable assets for a nation, especially one renowned as the birthplace of these innovations. Storytelling, particularly centered around products and services, emerges as a potent theme for promotion (Meldrum 1995). From a marketing perspective, the inventions of products and services serve as tools for the entities that created them for an extended period (Moriarty and Kosnik 1989; Beard and Easingwood 1996). In today’s diplomatic landscape, diplomatic representatives can actively seek and track such tech products, incorporating major inventions into the country’s storytelling. For instance, narratives could emphasize “The cutting-edge technology invented in our nation” or “The life-changing tech service produced by our country’s talented individuals” (Mashiah 2021). This form of storytelling highlights the global impact of products, showcasing how they contribute to societal changes and improve people’s lives, all rooted in progressive elements.

Conclusion and future research

Professionals in the field of international relations consistently embrace innovative approaches and channels to communicate diplomatic messages (Melissen, 2016). This brief article delves into the discursive dimension of tech diplomacy, establishing a groundwork for both national marketing research and the professional realm of public diplomacy. The discursive innovative process entails state actors strategically utilizing various elements to present the state positively, encompassing technological products, companies, entrepreneurs, and buzzwords. Meaningful rhetoric discussions hinge on actual progress within the nation’s high-tech industry. However, the use of specific rhetoric and the association between a country and its technology sector can carry negative implications, particularly when aspects of this industry are linked to scandals. Yet, as underscored in this article, such rhetoric serves as a versatile marketing tool to enhance a country’s reputation on the international stage.

Looking ahead, we will delineate potential directions for future research, underscoring the importance of exploring how countries worldwide employ these marketing practices. This may involve categorizing nations into advanced and technological versus undeveloped and investigating whether tech-diplomacy is specific to certain countries or a widespread phenomenon. Another prospective research avenue involves examining public perceptions to understand how the target audience interprets diplomatic tech messages. The goal is to evaluate the effectiveness of nations emphasizing their high-tech industry to position themselves as progressive entities in the eyes of diverse stakeholders, including business partners, diplomatic agents, tourists, and other global entities interacting with the promoting nation.

Figure 1. The components

Table 1. Diplomacy theories and their Google Scholar article count

Table 2. The roles of high-tech industry in the field of public diplomacy

References

Aydalot, P., and D. Keeble. 2018. “High Technology Industry and Innovative Environments: The European Experience.” Edited by P Aydalot and D Keeble. Routledge.

Bacon, G, S Beckman, D Mowery, and E Wilson. 1994. “Managing Product Definition in High-Technology Industries: A Pilot Study.” California Management Review 36 (3): 32–56.

Bayne, N, and S Woolcock. 2017. “What Is Economic Diplomacy?” In The New Economic Diplomacy, 17–34. Routledge.

Beard, C, and C Easingwood. 1996. “New Product Launch: Marketing Action and Launch Tactics for High-Technology Products.” Industrial Marketing Management 25 (2): 87–103.

Berridge, G R. 2022. Diplomacy: Theory and Practice. Springer Nature.

Blume, C, and M Rauchbauer. 2022. How to Be a Digital Humanist in International Relations: Cultural Tech Diplomacy Challenges Silicon Valley. Perspectives on Digital Humanism.

Buckup, S, and M Canazza. 2023. “What Is Tech Diplomacy and Why Does It Matter?” The World Economic. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/02/what-is-tech-diplomacy-experts-explain/.

Campbell, W K, and C Crist. 2020. The New Science of Narcissism: Understanding One of the Greatest Psychological Challenges of Our Time―and What You Can Do About It. Sounds True.

Craig, C, M A Flynn, and K J Holody. 2017. “Name Dropping and Product Mentions: Branding in Popular Music Lyrics.” Journal of Promotion Management 23 (2): 258–76.

Feijóo, C, Y Kwon, J M Bauer, E Bohlin, B Howell, R Jain, and J Xia. 2020. “Harnessing Artificial Intelligence (AI) to Increase Wellbeing for All: The Case for a New Technology Diplomacy.” Telecommunications Policy 44 (6): 101988.

Fontana, R, and L Nesta. 2009. “Product Innovation and Survival in a High-Tech Industry.” Review of Industrial Organization 34: 287–306.

Gooden, P. 2015. Name Dropping: A No-Nonsense Guide to the Use of Names in Everyday Language. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Griset, P. 2020. “Innovation Diplomacy: A New Concept for Ancient Practices?” The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 15 (3): 383–97.

Hadlock, P, D Hecker, and J Gannon. 1991. “High Technology Employment: Another View.” Monthly Lab. Rev 114: 26.

Höne, K. 2023. “What Is Tech Diplomacy?” https://www.ippi.org.il/what-is-tech-diplomacy/.

Horejsova, T, P Ittelson, and J Kurbalija. 2018. “The Rise of Techplomacy in the Bay Area.” Geneva: DiploFoundation and the Geneva Internet Platform. https://www.diplomacy.edu/event/hello-world-rise-tech-diplomacy/.

Ittelson, P, and M Rauchbauer. 2023. “Tech diplomacy practice in the San Francisco Bay Area.”

Klepper, S. 2001. “Employee Startups in High‐tech Industries.” Industrial and Corporate Change 10 (3): 639–74.

Klynge, C, M Ekman, and N J Waedegaard. 2020. “Diplomacy in the Digital Age: Lessons from Denmark’s TechPlomacy Initiative.” The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 15 (1–2): 185–95.

Leijten, J. 2017. “Exploring the Future of Innovation Diplomacy.” European Journal of Futures Research 5 (1): 1–13.

Lichtenstein, J. 2010. “Digital diplomacy.” New York Times Magazine 16 (1): 26–29.

Manor, I. 2019. The Digitalization of Public Diplomacy. Palgrave Macmillan.

Mashiah, I. 2021. “Come and Join Us”: How Tech Brands Use Source, Message, and Target Audience Strategies to Attract Employees.” The Journal of High Technology Management Research 32 (2): 100418.

———. 2022. Communication and High-Tech: Journalism, Public Relations, and Media Culture. Orion-Books Publishing House [Hebrew.

Mashiah, I, and E Avraham. 2019. “The Role of Technology and Innovation Messaging in the Public Diplomacy of Israel.” Journal of Global Politics and Current Diplomacy 7 (2): 5–28.

Meldrum, M J. 1995. “Marketing High‐tech Products: The Emerging Themes.” European Journal of Marketing 29 (10): 45–58.

Miremadi, T. 2016. “A Model for Science and Technology Diplomacy: How to Align the Rationales of Foreign Policy and Science.”

Moosavi-Movahedi, A A, and A Kiani-Bakhtiari. 2012. “Science & Technology Diplomacy.” Science Cultivation 2 (2): 71–76.

Moriarty, R T, and T J Kosnik. 1989. “High-Tech Marketing: Concepts, Continuity, and Change.” MIT Sloan Management Review 30 (4): 7.

Murray, S, P Sharp, G Wiseman, D Criekemans, and J Melissen. 2011. “The Present and Future of Diplomacy and Diplomatic Studies.” International Studies Review 13 (4): 709–28.

Rana, K S. 2007. “Economic Diplomacy: The Experience of Developing Countries.” In The New Economic Diplomacy: Decision-Making and Negotiations in International Economic Relations. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Salomon, J J. 1984. “What Is Technology? The Issue of Its Origins and Definitions.” History and Technology, an International Journal 1 (2): 113–56.

Saner, R, and L Yiu. 2003. “International Economic Diplomacy: Mutations in Post-Modern Times.”

Simelane, T. 2015. “Science and Technology Diplomacy and South Africa’s Foreign Policy.” South African Foreign Policy Review 2 (2): 41.

Sunami, A, T Hamachi, and S Kitaba. 2013. “The Rise of Science and Technology Diplomacy in Japan.” Science & Diplomacy 2 (1): 1–4.

Twenge, J M, and W K Campbell. 2009. The Narcissism Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlement. Simon and Schuster.

Vaughan, J. 2013. Technological Innovation: Perceptions and Definitions. American Library Association.

Wolf, M, and D Terrell. 2016. “The High-Tech Industry, What Is It and Why It Matters to Our Economic Future.”

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Virtual Diplomacy in India

- Parliamentary Diplomacy as ‘Track 1 1/2 Diplomacy’ in Conflict Resolution

- America’s Re-Engagement with the World and the Continued Importance of Diplomacy

- The Mindful Diplomat: How Can Mindfulness Improve Diplomacy?

- Knowledge Diplomacy and the Future(s) of Global Cooperation

- Sino-Taiwan Chequebook Diplomacy in the Pacific