While dealing with ways to counter religiously motivated terrorism or violent extremism, it is essential to begin by understanding the fundamental nature of violent extremism as an evolutionary concept that morphs based on temporal, cultural and geopolitical circumstances (Borum 2011, 1-6). Religiously motivated violent extremism is generally defined as an act committed to humiliate and kill all those who may dare to challenge or defy the hegemony of the God of perpetrator’s choice. While it may seem senseless mass slaughter to most, to the terrorists and their sympathisers, it is redemption (Simon and Benjamin 2002, 40). More often than not, the response to such acts of violence is delivered through the deployment of disproportionately higher levels of aggression, mostly through a militarised mechanism. America’s response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks is a case in point. However, to estimate the veracity of such a response, one needs to first appreciate how an individual travels through a pathway that leads to violent extremism. We will use what, in the authors’ view, is the most comprehensive model available to understand the pathways to violent extremism – and then study the efficacy of the militarised response mechanisms by comparing them with the results such approaches have achieved. The article thereafter attempts to prescribe alternative models for countering violent extremism (CVE) to demonstrate their effectiveness and conclude that a contextually relevant and blended (hard and soft) approach has historically proven to be most effective.

Understanding the Pathways to Violent Extremism

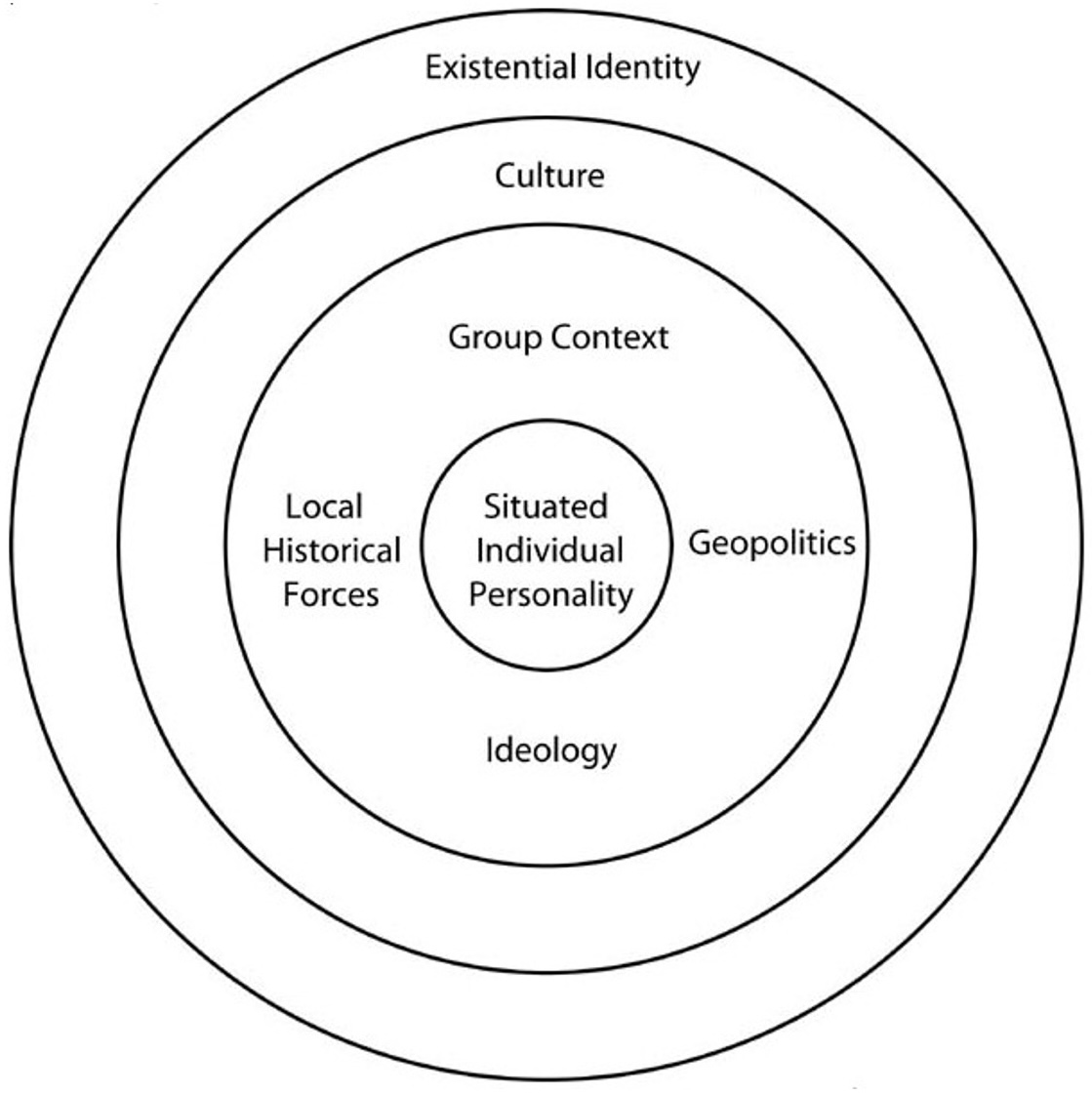

As John Horgan stated, it is more important to focus on how people acculturate themselves into violent extremism than on why they do so (2008, 80-94). While there are several models that have been proposed, especially in the post-9/11 era, the authors here rely on the Radical Pathway (RP) framework as espoused by Kumar Ramakrishna (2009, 25-31). The choice of this framework over other models stems from the fact that it offers a multidimensional approach. Unlike other, mostly linear models, it explores the interplay of various socio-cultural as well as geopolitical factors and how the output of such chemistry may impact different individuals uniquely. Thus, the RP framework is not only multi-faceted, it also appreciates the inimitability of individual personalities and their ability to respond to a certain concoction of life’s realities distinctively.

The Radical Pathway framework (see Figure 1) is anchored on the work of Geert Hofstede and Gert Jan Hofstede (2005). It leverages four concentric circles or layers revolving around an individual. While retaining Hofstedes’ three elements of Culture, Human Nature, and Individual Personality, the framework takes a more nuanced approach and attempts to refashion them in some ways. At the core of this model is the ‘Situated Individual Personality’ whose innate nature is influenced by the culture she or he is exposed to. However, according to Ramakrishna, the dynamics of the individual’s situation: geopolitical realities, ideologies and small group influences, shape her or his outlook towards their existential realities. It is in this context that when the individual perceives an ‘Existential Reality Threat’, she or he is transitioned from a non-violent person (who may or may not be radical in her or his views) into a violent extremist. What this framework and others like it tell us is that violent extremism is a product of complex interactions of personality traits, situational context, and perceptions. As such, the response to violent extremism or CVE should also be nuanced enough and not a unidimensional, force-on-force approach.

As are the triggers to violent extremism varied, so are the levels of threats emanating out of it. Given this reality, the CVE response mechanism should take into account the threat levels as well as the second and tertiary order consequences of such responses. Hence, a response divorced of the appreciation of the various factors involved and the threats emanating thereof may lead to a Sisyphean cycle of endless conflict.

America’s War on Terror

The militarised response to 9/11 by America and its allies is what can be characterised as a hard approach to CVE. Andrew J. Bacevich has defined the War on Terror as a succession of three rounds. Round one he says, is the technology-driven swift action war which was personified by the Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld. Round two was the counter-insurgency strategy led by General David Petraeus, which was the fundamental logic behind the surge. Round three had a rather discrete poster boy; Under Secretary of Defense Intelligence of the Obama administration, Michael Vickers, who was an accomplished CIA officer of the Afghan Jihad vintage. His approach seemed to mirror that of the enemies he was fighting in some ways. A key component of this was targeted killings of both potential and acting terrorists with more than its fair share of collateral damage. The Obama administration’s controversial drone program was a direct fallout of such strategies.

The failure of the War on Terror is almost too apparent. Data suggests that in the 15 years preceding 9/11 (1986-2001), there were four terror attacks in America killing 10 Americans while in the next 15 years, there were eight attacks killing 88 Americans. Similarly, the number of Islamic terror groups in the world was 13 in the period of 1986-2001. While in 2015, the number had shot up to 44. Given the above data as well as with the advent of Taliban 2.0 in Afghanistan, it can be argued that the impact of the War on Terror has actually been counter-productive. As Peter Byrne points out, there has been a surge in terrorism both in Iraq and Afghanistan as a result of troop surges. Byrne ascribes this to the nature of terror groups which he labels as “anti-fragile.” These groups, he posits, strengthen under attacks and have shown the ability to operate fairly independently in relation to their central command-and-control structures. Byrne also asserts that the harder these groups are hit, the easier it becomes for them to maintain a steady supply of new recruits, a second-order consequence of the War on Terror. This merits an inquiry into what led to such a failure of the United States military. We attempt to analyse this in the next section.

Addressing What Needs to be Addressed and Not What is Popular/Convenient

A question often asked is how to defeat a guy who looks down the barrel of a gun and sees heaven. A further extension of this question would be to answer it in a group context. For a successful CVE campaign, identifying the center of gravity of the adversary is critical. More often than not, it is seen, that the center of gravity of violent extremist groups is not their military might. Hence trying to tackle these groups militarily only augments the problem. Like in the War on Terror, a similar lesson can be drawn from the counter-productive initial British strategy of Battalion-Swipe in their Malaya campaign (Nagl 2002, 59-65). Global experiences have shown that the center of gravity in a counter-terror or counter-insurgency campaign is the hearts and minds of the populace, thereby diminishing and neutralising the violent extremist groups’ most potent weapon, their ideology. In order to drive home this point, the authors chronicle their own experiences in CVE campaigns in India’s Northeast, which has witnessed some of the bloodiest and yet grossly under-researched militancies of the world.

India’s handling of the secessionist insurgency in Assam is an interesting and yet little-known successful CVE campaign. As Deputy Inspector General, Eastern Range (DIG-ER), Assam Police, one of the authors was at the spearhead of combating a raging secessionist insurgency led by a group, United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA). ULFA has been fighting the Indian state since the mid-1980s (Waterman 2023, 279-304). It was a period in Assam’s history when bomb blasts, killings, kidnappings, etc. were not the exception but more of a norm (Gohain 2007, 1012-1018). In response to this, the Indian state declared Assam as a disturbed area which enabled the application of the controversial Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 or AFSPA. Consequently, the Indian Army was deployed and was designated as the lead agency in the counter-insurgency operations. The Army launched Operation Bajrang in 1990 followed by Operation Rhino in 1991. However, while there were definite tactical victories, at a strategic and operational level, significant results were missing (Baruah 1994, 863-877).

It is with this backdrop that one of this article’s co-authors took charge as DIG-ER in 2004. As a son of the soil, the author had a keen understanding of the insurgency terrain. It was clear to him that while carrying out surgical counter-insurgency operations at a tactical level was imperative; the real challenge was to defeat the ideology and the propaganda disseminated by ULFA against the Indian state. Thus, he developed a three-pronged approach. The first part of this was to closely coordinate tactical counter-insurgency operations among all agencies including the Indian Army, state police and the central intelligence agencies, thereby eliminating potential fratricides or even “unintentional” sabotage of counter-insurgency operations by individual agencies. This gave an instant fillip to the success rates of such operations thus leading to significant casualties within the ULFA camp.

Secondly, the author worked out a plan for winning the support of the community through various outreach initiatives. Most notable among them was Project Aaswas, whereby children whose family members were killed in violence, their sustenance and education was taken care of by the police. Such was the impact of this initiative that even UNICEF as well as the Ministry of Home Affairs, India joined hands with Assam Police subsequently (Kalita and Saikia 2018, 86). The project, along with several other outreach programs debunked the narrative of ULFA that security forces were only the perpetrators of violence and the community gradually started disassociating from the insurgents’ cause.

Finally, the key focus of the counter-insurgency campaign was intelligence and information operations. Concerted efforts were made to counter the secessionist propaganda of the insurgents that the Indian state was an occupying force in Assam. This was done by disseminating factual information on how Assam has been a part of the Indian milieu since as early as the 15th century through newspapers, radio broadcasts, and public meetings in almost every village. On the intelligence side, family members of insurgents were approached who would make appeals to the insurgents on radio programs to come overground and join the mainstream. This led to significant upheaval within the rank and file of ULFA when they heard their loved ones on the radio entreating them to shun the jungle life and come home. Another part of the intelligence operation was to penetrate the key strike force of ULFA, the A and C Companies (Coys) of its dreaded 28th Battalion, also known as the Kashmir Camp, which was operating from across the border in Myanmar. In order to win the trust of the commanders of this battalion, the author had several top-secret meetings with them and assured them of fair treatment if they were to suspend the ULFA cause and join the mainstream. It is interesting to note here that it was these very commanders who had made unsuccessful attempts on the author’s life and had even previously issued a “death warrant” against the author. These negotiations led to the historic “ceasefire” of the A and C Coys of the 28th Battalion of ULFA on 24th June, 2008 – which was essentially a surrender of the insurgents for all practical purposes. The impact of this operation was such that the number of fatalities of civilians and security forces in Assam fell from 418 in 2008-09 to 103 in 2010-11.

Another successful CVE campaign was the Filipino state’s countering of the Mindanao crisis through a Whole of Society approach. Retired Lt. General Benjamin Dolorfino was the Commander of forces that managed this crisis and espouses that the key was the battle of hearts and minds which could not be won by arms and bombs alone (Dolorfino 2011, 36-50). According to him, it required a Whole of Society approach which was not bereft of the legitimate use of adequate and targeted force. The model Dolorfino presents is in the form of an analogy: Terrorism is like a tree with multiple branches. The leaves are the violent extremist group members or the situated individuals and the branches, their leaders and the groups. The root, however, represents a multidimensional problem; military, socio-economic, political, as per this model. He recommends that a hard approach is required to cut away the branches. By this, he refers to leadership neutralisation as well as group neutralisation. This, he urges, is important to disassociate the leaves from the roots. Such a strategy is imperative to provide for the much-needed operational space to address the more fundamental problems of the root.

For Dolorfino, Violent Extremism, like insurgency, is often not merely a military issue. He concedes that violence and social-order related challenges are physical manifestations of deeper societal problems. Hence, unless adequate attention is diverted to the roots, new branches and thereby new leaves will come up. To address the root, he recommends a Whole of Society approach which involves three components: the people or the society, the government as well as the security apparatus. According to the General, if people are not made a key stakeholder in the Whole of Society approach to CVE, there cannot be lasting peace. True peace, according to him, is achieved when the people create peace for themselves. Peace cannot be imposed, he posits. Dolorfino attests that fighting terrorists and fighting terrorism are two different things. Hard approaches are important to fight terrorists (leaves and branches). Terrorism, however, is a societal challenge stemming out of the roots and thus needs a Whole of Society approach to deal with.

While both the above cases have components of hard and soft approaches in varying degrees, it is important to also consider the specifics of a hard approach or else there may be splinter effects. This could mean the formation of newer, deadlier groups. The invasion of Iraq by allied forces and the subsequent rise of Daesh is clear evidence of such a phenomenon (Brands and Feaver 2017, 7-54). This is because violent extremist groups are “anti-fragile” – they display an ability to metamorphosise into more violent versions of their original avatars. Hence, leveraging the appropriate instrument of power is critical to prevent second and tertiary order problems for the future. Global trends also support such assertions of the authors against a militarised approach to CVE.

A Rand Corporation study of 2008 analyses data of 648 violent extremist groups between 1968 to 2006. The data in the study reflects that only in 8% of the cases, a military campaign led to the neutralisation of a violent extremist group. In an overwhelming 83% of the cases, the neutralisation was achieved through a politico-constabulary approach. Using visibly fair law-enforcement approaches backed by intelligence support seemed to be the ideal option as per this report. Similar lessons can be drawn from the Briggs Plan of the British which leveraged a constabulary-led approach to eventually neutralise the Malayan Communist insurgency (Nagl 2002, 65-76).

Drawing upon the experiences of the authors, another empirical case of recent times supports the Rand Corporation study. This refers to how al Qaeda in Indian Subcontinent’s (AQIS) ansar (sleeper cell) networks were disrupted all across India in 2022-23. A huge network of over 60 cells was unearthed by the intelligence agencies and was arrested by the police forces. Instead of taking a militarised approach of neutralisation, the Indian agencies followed a law-enforcement and constabulary path. Aside from that, the Indian authorities reached out to the Muslim communities and made them a stakeholder in the process. This was in line with General Dolorfino’s model of community-based peacebuilding. In addition to that, the authorities worked in close collaboration with Muslim scholars, imams (preachers), and community leaders to reform the madrassa (religious school) education system with a goal to imbibe a more holistic education, including science, English language as well as vocational training which would empower the students to seek gainful employment in future. This was critical as some of these madrassa networks evolved as the epicenters of AQIS’s operations.

A Way Forward for Practitioners

The empirical evidence cited above demonstrates with some clarity that theoretical models, like the RP framework, may be adopted, albeit with some contextualisation, in order to evolve effective CVE programmes. We shall exhibit this further by plotting the ULFA experience on the RP Framework. As indicated earlier, a three-pronged approach was developed to counter the pogroms of the insurgents. The tactical counter-insurgency operations directed its focus on the circle immediately encircling the “Situated Individual” whereby the group tent which encased the individual was degraded through relentless and joint operations. The shrinking of the group, quite literally, played on the psyche of the individuals as they realised that the sense of security they enjoyed was only a mirage.

Another aspect of this was the developing geopolitical scenario of that time in the region. One of the key operational bases of ULFA was Bangladesh. The Bangladesh National Party (BNP) led government was at best ambivalent about the presence of major ULFA camps in their territory. However, by late 2007/early 2008, the political climate in Bangladesh was indicating a revival of Awami League (AL) government in the country. Historically, AL has been more sympathetic to India’s genuine security concerns. Thus, the operational leadership of ULFA was anticipating a major crackdown if AL came to power, which actuated post AL came to power in 2009. This pro-AL sentiment on ground was identified and exploited by Indian agencies to create a more conducive environment for the ULFA leadership to consider opening a backchannel negotiation with the author.

A key aspect behind the success of the CVE efforts against ULFA was the fact that the author, who was leading the efforts, was a product of the same socio-cultural realities in which the militants and their leadership peddled their nefarious agenda. Thus, in relative terms, it was easier for him to identify the fissures exploited by the militants and then develop counter-measures to plug such societal cracks. It also helped identify and address the manipulation of facts which was key to the militants’ propaganda warfare. Finally, the intelligence operations executed by coopting the families of the militants essentially rebooted their “Existential Realities” by helping them identify with a different in-group, their loved ones. Through sustained interventions, this created morale issues within the rank and file of ULFA which led to a potential mass exodus of cadres from the camps. This exerted further pressure on the leadership to develop pathways whereby a systematic “ceasefire” could be negotiated.

A similar exercise can be done for all the empirical cases presented here to prove the utility of a multi-faceted framework like the RP model, as a key to the success or failure of CVE operations. For instance, the operation against AQIS, where the authors were intimately involved can be briefly examined. By dispelling the propaganda of AQIS which it had disseminated within the community, the CVE operatives were able to shrink the operating environment for the terrorist group. Through persistent positive interventions, the Muslim community was able to identify AQIS as the “Existential Reality Threat” to their way of life and not the Indian state, as propagated by the terrorists. Thus, they played the role of the proverbial eyes and ears of the security agencies and helped identify the otherwise innocuous-looking sleeper cells embedded within their community, which would have been virtually impossible if the community was not coopted.

Distillation of the above examination displays a few clear factors which are essential components of any CVE strategy according to the authors. Firstly, a deep understanding of the socio-cultural context in which a violent extremist group thrives is imperative. When such understanding is lacking, the CVE strategist will not be able to accurately identify the lacuna in the terrorists’ propaganda and thereby will be ineffective in developing counter-measures. A case in point would be the lack of understanding of the tribal culture of Afghanistan by the coalition forces – a key factor in the reemergence of the Taliban. It is in this context that the authors promote an intelligence-driven, constabulary approach to CVE since such a force will have to be an indigenous unit which emanates out of the same socio-cultural environment as that of the violent extremist actors. The next factor that emerges is the cooption of all stakeholders in the peacebuilding initiative. This would include the various security forces, civilian agencies, as well as the populace to jointly counter the devious designs of violent extremist groups. It is critical for the CVE strategist to create pathways whereby the populace starts identifying the terrorists as the real threat to their “Existential Realities” and not the CVE forces. Finally, a keen understanding of the broader geopolitical context in which a conflict exists and the ability to exploit the same to further one’s strategy goes a long way in creating an atmosphere where neutralisation of violent extremist groups is conducive. However, the authors firmly advocate a coordinated and relentless tactical counter-insurgency operation in order to prove to the adversaries the futility of their opposition in the face of surgical operations targeted at their leaderships, across levels.

Conclusion

When it comes to countering violent extremism, a one size fits all approach does not work. A key reason for this is that individuals and groups that engage in violent extremism are unique. Hence, a nuanced method, using a blend of hard and soft approaches, is a practicable way forward. It is also emphasised that the formula for the mix of hard and soft approaches is contextual and depends on the human, cultural, and political terrains where CVE campaigns are executed. Sound and multi-dimensional theoretical models should be a critical ingredient in countering violent extremism policymaking as such models provide an important reference-point for policymakers and strategists who may sometime lose sight of the larger policy goals while focusing on operational and tactical levels.

Figure 1: Radical Pathway Framework

Bibliography

Ahmed, Farzadan 1991. “Various army operations launched against ULFA.” India Today. October 15, 1991. https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/special-report/story/19911015-various-army-operations-launched-against-ulfa-814916-1991-10-14.

Bacevich, Andrew J. 2012. “War on Terror: Round 3.” Los Angeles Times. 19 February 2012. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/la-xpm-2012-feb-19-la-oe-bacevich-war-on-terror-round-three-20120219-story.html.

Baruah, Sanjib 1994. “The State and Separatist Militancy in Assam: Winning a Battle and Losing the War?” Asian Survey 34, no. 10: 863–877. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.1994.34.10.00p04306.

Basumathary, Rinoy 2018. “Assam: Kokrajhar observes International Youth Day with thrust on human trafficking.”Northeast News. August 13, 2018. https://nenow.in/north-east-news/assam-kokrajhar-observes-international-youth-day-thrust-human-trafficking.html.

Borum, Randy 2011. “Rethinking Radicalization.” Journal of Strategic Security 4, no. 4: 1-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.4.4.1.

Brands, Hal, and Peter Feaver 2017. “Was the Rise of ISIS Inevitable?” Survival (London) 59, no. 3: 7–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2017.1325595.

Byrne, Peter 2017. “Anatomy of terror: What makes normal people become extremists?,” NewScientist. August 16, 2017. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg23531390-700-anatomy-of-terror-what-makes-normal-people-become-extremists/.

Cohen, Michael 2012. “General David Petraeus’s fatal flaw: not the affair, but his Afghanistan surge.” The Guardian. November 13, 2012. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/nov/13/general-david-petraeus-flaw-surge-afghanistan.

Das, Mukut 2022. “Al-Qaida chief Aymenn al-Zawahiri’s ‘go to Assam’ call disturbing: Cops.” The Times of India. July 29, 2022. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/guwahati/cops-al-qaida-chiefs-go-to-assam-call-disturbing/articleshow/93197439.cms.

Data are from the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). “Global Terrorism Database, 2016.” Accessed on October 5, 2023. https://www.start.umd.edu/pubs/START_AmericanTerrorismDeaths_FactSheet_Sept2016.pdf.

Dean, Aimen, Paul Cruickshank, and Tim Lister 2018. Nine lives: My time as MI6’s top spy inside Al-Qaeda. (London: Oneworld Publications).

Dolorfino, Lt. Gen. Benjamin 2011. “The Mindanao Security Situation: A “Whole-Society” Approach towards Peace.” in Peace, Autonomy, and Democracy in Mindanao: Proceedings of a Roundtable Discussion (Makati City: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung/Philippine Council for Islam and Democracy): 36-50.

Gladwell, Malcolm 2004. Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make Big Difference. (London: Abacus): 25.

Gohain, Hiren 2007. “Chronicles of Violence and Terror: Rise of United Liberation Front of Asom.” Economic And Political Weekly 42, no. 12: 1012–1018. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4419382.

Hofstede, Geert and Gert Jan Hofstede 2005.Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. (New York: McGraw-Hill).

Horgan, John 2008. “From profiles to pathways and roots to routes: Perspectives from psychology on radicalization into terrorism,” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 618: 80–94, DOI: 10.1177/0002716208317539.

Hussain, Wasbir 2022. “The ULFA Mutiny.” Outlook. February 03, 2022. https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/the-ulfa-mutiny/237821.

Jones, Seth G. and Martin C. Libicki 2008. How Terrorist Groups End: Implications for Countering al Qa’ida. (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation). Accessed on October 5, 2023. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9351.html.

Kalita, Hriday Ranjan and Jyoti Prasad Saikia. 2018. “Impact Of Armed Conflict Upon Women: A Qualitative Analysis From A Gendered Perspective.” International Journal of Advance and Innovative Research 5, no. 4 (October-December): 81-88.

Khan, Omer Farooq 2021. “Will Taliban succeed in governing Afghanistan?” The Times of India. September 22, 2021. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/south-asia/will-taliban-succeed-in-governing-afghanistan/articleshow/86417495.cms.

McVeigh, Karen 2012. “Obama ‘Drone-Warfare Rulebook’ Condemned by Human Rights Groups.” The Guardian. 25 November 2012. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/nov/25/obama-drone-warfare-rulebook.

Nagl, John A. 2002. Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam. (Chicago & London: The Chicago University Press): 59-65.

Ramakrishna, Kumar 2009. Radical Pathways: Understanding Muslim Radicalization in Indonesia (London and Westport, Conn: Praeger Security International): 25-31.

Simon, Steven and Daniel Benjamin 2002. “Age of Sacred Terror.” (New York: Random House): 40.

Singh, Bikash 2023. “Citizens from Muslim community becoming stakeholders in Assam govt’s fight against radical elements: CM Himanta Biswa Sarma.” The Economic Times. January 01, 2023. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/india/citizens-from-muslim-community-becoming-stakeholders-in-assam-govts-fight-against-radical-elements-cm-himanta-biswa-sarma/articleshow/96665995.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst.

Staff Reporter 2023. “Muslim Leaders Extending Support to police, govt for reforming private madrassas: Assam DGP.” News Live. January 23, 2023. https://newslivetv.com/muslim-leaders-extending-support-to-police-govt-for-reforming-private-madrasas-assam-dgp/.

Thrall, A. Trevor, and Erik Goepner 2017. “Step back: lessons for US foreign policy from the failed WoT.” Cato Institute, Policy Analysis 814. Accessed on October 5, 2023. https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/step-back-lessons-us-foreign-policy-failed-war-terror#objective-1-preventing-terrorist-attacks-in-the-united-states.

Waterman, Alex 2023. “The Shadow of ‘the Boys:’ Rebel Governance Without Territorial Control in Assam’s ULFA Insurgency.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 34, no. 1: 279–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2022.2120324.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Assessing Changes in How Australia Refers to Extremism

- Violence in the West African Sahel is not about Terrorism

- Afghanistan: A Subaltern State Suffering from Terrorism

- Considering the Whole Ecosystem in Regulating Terrorist Content and Hate Online

- Terrorism in Africa: Explaining the Rise of Extremist Violence Against Civilians

- American Foreign Aid and Colombia’s Human Rights Tragedy