This case study is an excerpt from McGlinchey, Stephen. 2022. Foundations of International Relations (London: Bloomsbury).

The World Economic Forum, founded in 1971, has become prominent in international affairs owing to its yearly meeting at the Swiss mountain resort of Davos. For many years it restricted itself to inviting business leaders from Western Europe, before gradually opening up to the rest of Europe and the United States. The annual meeting has grown to serve as an informal international summit of the world’s top economic, business and political leaders. In recent years, the Forum has also offered heads of state from emerging powers of the Global South the opportunity to make the keynote address at the annual meeting – China in 2017, India in 2018 and Brazil in 2019. In this respect, despite its location in the West, the World Economic Forum is giving space to Southern leaders to bring their contributions to and visions of international politics into the limelight.

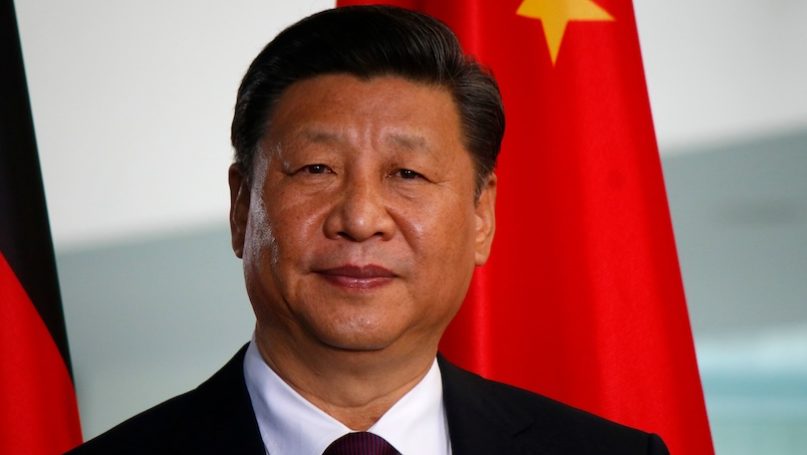

In 2017, President Xi Jinping’s presence at Davos represented the first time a Chinese head of state attended the event. The themes contained in Xi’s keynote address suggested a different place for China in the international order: as the leader and shaper of, rather than most prominent challenger to, global governance and the international order. China has historically had a mixed relationship with the idea of globalisation. Beginning in the late 1970s under Deng Xiaoping, China had opened its economy to globalisation while remaining politically ‘communist’. This has been described as ‘communism with Chinese characteristics’. In his speech, Xi launched a staunch defence of economic globalisation, arguing that it has caused tremendous social, scientific and technological progress. Xi went on to highlight that the world needs to work together to drive and sustain growth in the global economy and overcome crises. To do so, it needs an effective global leader at the helm steering the global economy, and since developing countries account for the majority of global economic growth, that leader should come from the South. More specifically, that leader should be China, as it will be attuned to addressing the needs of the developing South and global inequalities while simultaneously instilling and spearheading a dynamic and technologically driven global economy (Kennedy 2018).

Xi’s speech exuded a lot of the rhetoric about the market economy that Western industrialised states normally use. It was also conveyed in a manner that suggested that the major problems lay elsewhere – not in China – and China could proffer good global solutions. Again, this was a style of delivery and content ordinarily associated with the Western leaders of the so-called liberal international order. Xi’s address marked an inflection point in international politics. It was made at a time when US President Donald Trump was pursuing policies and rhetoric that seemed to amount to the United States retreating from its position as global leader, as evidenced through Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement, the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the 2015 nuclear agreement with Iran. Xi therefore positioned himself as the new leader of the world (although, not the ‘free’ world), which would additionally benefit the Global South given China’s concern for the developing world via its own Southern heritage.

It remains essential to parse the reality of Chinese intentions from the rhetoric. Since the 2017 speech, China’s relations with several countries in the Asia-Pacific – Australia, India, Malaysia, Sri Lanka – have deteriorated significantly. Issues of contention include territorial conflict, foreign political influence and unsustainable debt created by BRI lending. Indeed, Xi’s speech at the 2021 Davos summit struck a far more assertive tone. China has also faced international pushback because of its mishandling of the initial outbreak of Covid-19. Yet, these tensions do not occur in isolation. Trade with China, while witnessing some decline, has remained high, with China continuing to serve as the largest trade partner for several countries.

An analysis of Xi’s speech and subsequent events points to elements of a multiplex world order – characterised by multiple and overlapping realms of cooperation and contestation. While the US is no longer a worldwide hegemon, China does not simply replace it. Global governance in the multiplex world order would be neither parochially Southern nor anti-West, but rather a mix of both. The large, universally beneficial elements of the post-1945 liberal international order would remain, but would be strengthened by Chinese cognisance of and experience with the issues of developing countries. Traditional issues of national security remain significant, but alongside a range of other issues that constitute international relations.

This case study exemplifies the essence of a global perspective – draw on and highlight the experiences and ideas of the neglected parts of the world, namely the Global South, in order to enrich existing concepts through diversification, not replacement. Scholarship in the so-called ‘Chinese school’ of International Relations has been pioneering in this respect (see Zhang and Chang 2016). Zhao Tingyang (2019) has adapted the concept of ‘tianxia’, or ‘all under heaven’, which formed the basis of the historical Chinese Empire, to outline its relevance to the contemporary world order by highlighting the ‘all-inclusiveness’ principle that promotes global harmony. Yan Xuetong (2011), drawing on ancient Chinese history, has asserted the importance of ‘morality’ in international affairs in conjunction with state power. Similarly blending Chinese political thought with Western social theory, Qin Yaqing (2018) has stressed the importance of analysing relations among international actors, rather than studying them separately.

The above case does, however, also highlight possible divisions within the Global South itself. China represents the ‘power South’, not the ‘poor South’ (Acharya 2018). Privileging China’s position as Xi seeks, may come at the expense of continuing to neglect poorer and less prominent states. However, as the world becomes more interconnected and globalised, one could imagine significant effects on the practice of international relations itself. As the concept of a multiplex world order envisions, other fora focusing more on Southern issues – and hosted in Southern locations – such as the BRICS have emerged, altering the landscape of global economic governance. If these initiatives sustain strength and momentum, global stewardship by Southern leaders, as displayed by President Xi at Davos, could become the norm rather than the exception.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Towards Global International Relations

- Student Feature – Theory in Action: Global South Perspectives on Development

- The United Nations Environment Programme in Nairobi, Kenya

- Student Feature – Theory in Action: Asian Perspectives on a ‘Chinese School’

- Images of China’s Belt and Road Initiative

- Student Feature – Theory in Action: Towards a Global IR?